The end of Exodus details the construction of the tabernacle (Exod 25–40). The first part of Numbers recounts the arrangements made for Israel’s journey from Sinai to the promised land with the tabernacle in the midst of the camp (Num 1–9). Leviticus stands between these two, listing the regulations for the tabernacle of the Lord’s presence and for the Israelite community that surrounded it.

Author and Date

The date and authorship of Leviticus are bound up with that of the Pentateuch as a whole, especially Exodus through Deuteronomy (see Introduction to the Pentateuch). Exodus and Deuteronomy explicitly state that Moses himself wrote down certain substantial portions of the Pentateuch (e.g., Exod 17:14; 24:4, 7; 34:27; Deut 31:9, 19, 22, 24–26). There is no such statement anywhere in Leviticus, but there does exist a constant stream of references throughout the book stating that God spoke these regulations and stories to and through Moses (sometimes along with Aaron); see, e.g., 1:1; 4:1; 5:14; 6:1, 8, 19, 24; 7:22, 28. Moreover, the final notices refer to Moses as the mediator of the revelation at Sinai (26:46; 27:34; cf. 16:34b).

Major Theological Themes

The theological focal point of Leviticus is God’s presence in the midst of Israel. Sinai was “the mountain of God” (see Exod 3:1 and note; 4:27; 18:5; 24:13), and the tabernacle was his tent. As the tent of the Lord, the tabernacle went with the Israelites in the midst of their tents. Along with God’s presence, of course, comes the need for holiness, purity, and atonement, all of which are also key theological themes in Leviticus.

The Lord’s Presence

After almost a year at Sinai, the tabernacle was erected (Exod 40) and the glory cloud of the Lord so filled the tabernacle that Moses could not even enter the tent (Exod 40:34–35). Therefore, the Lord spoke the tabernacle sacrificial regulations in Lev 1–7 to Moses “from the tent of meeting” (1:1). The glory cloud of the Lord’s presence (with fire in it by night) had led them from Egypt to Sinai (Exod 13:20–22; 14:19–20, 24; 16:10), and now it would lead them from Sinai through the wilderness and eventually to the promised land (Exod 40:36–38). Num 1–9 recounts the preparations of the camp and concludes in 9:15–23 with an extended reference back to the pillar of cloud and fire occupying the tabernacle in Exod 40:34–38. When the glory cloud finally lifted up over the tabernacle and set out for the promised land, the camp followed (Num 10:11–13). Centuries later the same glory cloud of the Lord’s presence would occupy Solomon’s temple (1 Kgs 8:10–11; 2 Chr 5:11–14; 7:1–3).

The Lord said in the blessings of the covenant, “I will put my dwelling place among you, and I will not abhor you. I will walk among you and be your God, and you will be my people” (26:11–12). His presence among them was a key factor in their identity as the people of God. It was a promise Moses had depended on since the burning bush (Exod 3:12) and through some especially difficult times (e.g., the golden calf incident in Exod 33:15–16). Unfortunately, by the time of the Babylonian captivity, the Israelites had so desecrated and defiled the temple that the glory cloud (presence) of the Lord actually departed from it, abandoning it to destruction (Ezek 8:2–4; 10:3–4, 18–19; 11:22–25).

The NT develops the themes of the tabernacle and the temple and God’s glory and presence in them by noting their fulfillment in Jesus Christ, in the church, and in the believer. John 1:14 says, “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling [i.e., pitched his tent or tabernacled] among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the one and only Son, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth.” And Jesus himself prayed to the Father just before he went to the cross that the world would also see his glorious presence in the unity of believers (John 17:22–23a).

Paul develops this theme on the level of both the individual Christian (1 Cor 6:18–20; 2 Cor 6:14–18) and the Christian community, the body of believers. He treats the latter most extensively in Eph 2–3 (cf. 1 Cor 3:9–17). We are all “fellow citizens . . . [and] members of [God’s] household . . . a holy temple in the Lord . . . being built together to become a dwelling in which God lives by his Spirit” (Eph 2:19–22). In Eph 3:14–21 Paul returns to the theme of the church as the temple of the Holy Spirit filled with God’s glory. Paul wants believers to be “filled to the measure of all the fullness of God” (Eph 3:19; recalls the glory cloud filling the tabernacle and temple) so that there will be “glory in the church and in Christ Jesus throughout all generations, for ever and ever! Amen” (Eph 3:21). See “Temple.”

Holiness and Purity

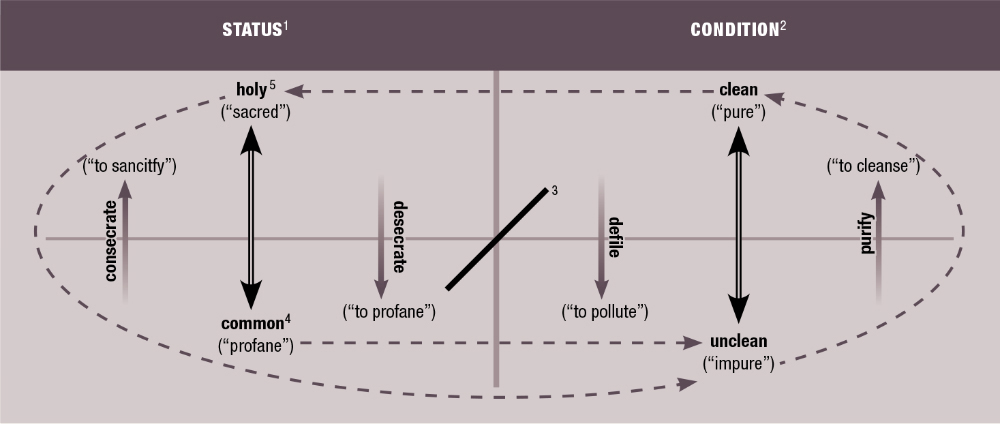

After the Lord consumed Nadab and Abihu with fire on the tabernacle inauguration day (10:1–2), he instructed the priests to “distinguish between the holy and the common, between the unclean and the clean” (10:10; cf. Ezek 22:26; 42:20; 44:23; 48:14–15). The two polarities—holy versus common (i.e., holiness) and clean versus unclean (i.e., purity)—are core issues in the theology of Leviticus precisely because the Lord was present, dwelling with them in the tabernacle. Neither holiness nor purity was limited to the tabernacle, of course, since the people themselves were a “holy nation” (Exod 19:6), and holiness and purity were to be maintained in the community as well, but the main concern was that no impurity from the community accrue to the tabernacle (Lev 15:31). (See “Holiness and Purity” and the explanation that follows.) Along with holiness and purity, 10:17 adds “atonement” as a third essential element: the sin offering “is most holy” because “it was given to you [the priests] to take away the guilt of the community by making atonement for them before the LORD.” Atonement was the means by which they would deal with problems that arose in the realms of holiness and purity.

Numerals 1–5 on the chart above correspond to (1) the “status” of a person, place, or thing as either “holy” or “common” (see the left side of the chart; Lev 10:10a), (2) the “condition” of a person, place, or thing as either “clean” or “unclean” (see the right side of the chart; Lev 10:10b), (3) the main concern that nothing unclean come into direct contact with that which is holy (the diagonal bar through the middle of the chart blocking the way between holy and unclean), and (4–5) whenever either a holy or a common person becomes unclean they must first ritually “purify” (= “cleanse”) their body before they approach that which is holy (see the arrowed lines going from both holy and common to unclean and from there to clean).

As for holiness (see “holy” versus “common” in 10:10a), since God is most holy and he dwelled in the tabernacle, the central place of holiness in Israel was the tabernacle, and the holy priests officiated there (8:10–15, 30; 10:3, 12–13, 17–18; 16:19, 24). In this sense and on this level, the priests had a holy status that the common people as a whole did not have. The noun “common” is sometimes translated “profane,” but the latter word has negative connotations in English that are not necessarily included in the Hebrew term. There was nothing essentially negative about being a common person, for example. It was the normal status of regular people. However, if someone or something was holy, to treat him, her, or it as if they were common would “profane” them (sometimes translated “defile,” “degrade,” “desecrate,” or “treat with contempt”; see 19:8; 21:4, 7, 9, 12, 14–15, 23; 22:9, 15–16; Ezek 7:21–22; 20:9, 14, 22; 23:39). Holiness was “graded” so that, e.g., the innermost cella (chamber) of the tabernacle (where the ark of the covenant was located) was the “Most Holy Place,” whereas the next cella leading into it was the “Holy Place” (Exod 26:33–35; cf. Lev 16:2, 16–17; see “Tabernacle Floor Plan”). Again, the Aaronic priests were holy as compared to the common Israelites, but the common Israelites were holy as compared to non-Israelites (Exod 19:6). So, e.g., the Lord commanded his people, “Be holy because I, the LORD your God, am holy” (19:2), so no one should “degrade” their daughter by making her a prostitute (19:29).

Purity (see “unclean” versus “clean” in 10:10b), on the other hand, was essential for approaching this holy God in whose presence they dwelled. This was a matter of the person’s condition, i.e., whether their body was ritually clean or unclean. If unclean, they must not enter the tabernacle lest they pollute it with uncleanness. This was most important (15:31). If a person was unclean, they should also avoid contact with other holy things lest they pollute them (e.g., 7:19–21). They should even avoid contact with other (holy or common) people lest uncleanness spread in the camp. Moreover, if they made any object unclean, a clean person who touched it became unclean (e.g., 13:45–46; 15:1–12). Avoidance of such people or objects was intended to prevent spreading uncleanness throughout the camp (cf. Hag 2:11–13). There was nothing essentially wrong with becoming “unclean” as long as one handled it properly. In fact, becoming unclean could hardly be avoided. Even priests became unclean (e.g., they could marry and have sexual intercourse, which would make them unclean for that day, 15:16–18). An unclean priest could not enter the tabernacle to worship or serve there. However, even in their unclean condition their status as holy was maintained. They did not need to be reconsecrated to serve as a priest again the next day. Similarly, a common person could be either clean or unclean, but they could only enter the tabernacle in a clean condition.

Probably the best way to understand the ritual purification laws is to recall the manifest visible presence of God in the OT tabernacle and later in the temple (see Introduction: Major Theologial Themes [The Lord’s Presence]). This place of visible presence was precisely the focus of the priestly worldview and the theology with which the book of Leviticus is concerned. The ritual purity laws correspond to the visible presence of the Lord in the tabernacle. Since God was visibly present, the people needed to be ritually pure in his presence.

In the NT church, God is present with his people in a different way—by the individual and corporate indwelling of the Holy Spirit (see Introduction: Major Theological Themes [The Lord’s Presence]). There is no tent or building over which the cloud of God’s presence appears in a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night. The concern for purity shifts to the spiritual level since that is the level of the presence. Thus, we have passages like 1 Pet 1:22, “Now that you have purified yourselves [lit. “your souls”] by obeying the truth so that you have sincere love for each other, love one another deeply, from the heart” (cf. Matt 15:1–20). The purity needs to function on the same level as the presence. Thus, in the OT system there were physical washings. Of course, where God is present in a visible way, he is also present spiritually. Thus, the physical cleansing terminology is sometimes used for spiritual purity and cleansing even in the OT (e.g., Ps 51:2, 6–7, 10, 12, 16–17). Purity and holiness terminology therefore continues from the OT into the NT. Compare, e.g., how the woman was made “ceremonially clean” from her flow of blood after childbirth in 12:7 (cf. Luke 2:22) with Peter’s statement in the Jerusalem council: “He did not discriminate between us and them [i.e., Jews and Gentiles], for he purified their hearts by faith” (Acts 15:9). The ritual procedures for physical purity do not come through into the NT, but purity of the heart does (cf. Heb 9:13–14; 1 Pet 1:22). See “Holiness.”

Offerings, Sacrifices, and Atonement

The offerings and sacrifices were above all a means of worshiping the God who dwelled in the midst of Israel. Leviticus is concerned with the details of which offerings Israelites should make to God and how they should offer them. Atonement was the means God designed for them to deal properly with their sins and impurities and thereby avoid violating God’s holiness and purity. Lev 15:31 is particularly clear on this matter: “You must keep the Israelites separate from things that make them unclean, so they will not die in their uncleanness for defiling my dwelling place, which is among them.” The next chapter (ch. 16), highlights the importance of the Day of Atonement for cleansing the tabernacle from pollutions.

The English word “atonement” comes from combining the preposition “at” with Middle English “onement” (i.e., bringing together as one). Basically, it is concerned with making reconciliation. The Hebrew verb itself (kipper) means primarily to purge or wipe away, but the overall effect of doing this was indeed reconciliation. Therefore, the Hebrew verb and other forms of the same word group can mean “to ransom” (= to make a payment to appease; e.g., kōper [“ransom”], kipper [“to atone”], and kippurîm [“atonement”] in Exod 30:11–16). The same Hebrew verb appears numerous times in the sin and guilt offering regulations (4:1—6:7) precisely because the actual focus of those two offerings was on making atonement for the various kinds of holiness and purity issues that would arise.

The purpose of the Day of Atonement was to cleanse the tabernacle. It was the culmination of the sacrificial procedures for the year that went before it. There were three sin offering animals on that day: a bull for the priests and two goats for the sin offering of the people; one of the goats was slaughtered, and the other was sent away as a scapegoat (16:5–10; both goats are included in the “sin offering” in v. 5 even though the scapegoat was not to be slaughtered). The slaughtered sin offerings for the priests and the people purged the tabernacle itself from its impurities all the way into the Most Holy Place, where the ark of the covenant was behind the veil, and out to the burnt offering altar near the entrance to the tabernacle (16:11–19; cf. 16:32–33; see “Tabernacle Floor Plan”). Then the high priest loaded the iniquities of the whole community onto the live scapegoat so that it could take them as far away as possible from the Israelite community, thus removing the iniquities into the wilderness, never to return (16:20–22). Both the tabernacle and the community, therefore, had a new start for the upcoming year.

In the NT sacrifice of Jesus Christ, he himself made atonement for those who put their faith in him as their Savior (Rom 3:24–26). The priests applied the blood of the OT sacrifices to the tabernacle on earth (see “Tabernacle Floor Plan”), but the blood of Jesus was applied to the tabernacle in heaven, the very throne room of God (Heb 9:6–14, 23–24). Furthermore, in the OT the people had to continue offering their sacrifices year after year, but in the NT Jesus offered himself as the sacrifice on our behalf “once for all” (Heb 9:25—10:4). Jesus is the ultimate “sin offering” (Rom 8:3) and the new covenant ratification sacrifice (Luke 22:19–20). The point is this: Jesus fulfilled all the sacrificial requirements for us.

Many of the basic principles of the sacrificial system apply not only to Christ but also to the life of the Christian. If we are going to be like Christ, we need to give ourselves as sacrifices, like he did. The burnt offering, e.g., is the primary background for Rom 12:1: “Offer your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God—this is your true and proper worship.” We are “a holy priesthood, offering spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus Christ” (1 Pet 2:5b). Our worship of God and our good works for him are our “sacrifices” (Heb 13:15–16; cf. Phil 4:18). Paul also uses sacrificial terminology to describe the fruits of his ministry of the gospel (Rom 15:16; Phil 2:17). See “Sacrifice.”

Outline

Leviticus divides naturally into two major sections, chs. 1–16 and chs. 17–27. The first half focuses primarily on regulations for the tabernacle; the second half focuses on the importance of purity in the community that surrounded the tabernacle. Ch. 16 binds the two halves together by concluding the first half and leading into the second.

I. Laws of the Tabernacle (1:1—16:34)

A. Sacrifices and Offerings (1:1—7:38)

1. Description of the Rituals (1:1—6:7)

2. Distribution of the Sacrificial Portions (6:8—7:38)

B. The Ordination of Aaron and His Sons (8:1–36)

C. The Priests Begin Their Ministry (9:1—10:20)

D. Purity Regulations (11:1—15:33)

E. The Day of Atonement (16:1–34)

II. Laws of the Community (17:1—27:34)

A. Eating Blood Forbidden (17:1–16)

B. Laws of Community Holiness (18:1—26:46)

1. Unlawful Sexual Relations, Various Laws, and Punishments for Sin (18:1—20:27)

2. Rules for the Priests and Unacceptable Sacrifices (21:1—22:33)

3. The Appointed Festivals, Sabbath Year, and Year of Jubilee (23:1—25:55)

4. Reward for Obedience and Punishment for Disobedience (26:1–46)

C. Redeeming What Is the Lord’s (27:1–34)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()