Deuteronomy is both the climax of the Pentateuch (the five books of Moses that the Bible begins with) and the introduction to the historical books, particularly Joshua, Judges, 1-2 Samuel, and 1-2 Kings. The historical books view Israel’s past through the lens provided by the book of Deuteronomy, particularly the blessings and curses of chs. 27–28.

The Greek translators mistakenly entitled this book “Deuteronomy,” meaning “second (deutero) law (nomos).” This was based on a translation of the Hebrew word for “copy” in 17:18, where the king is commanded to make a copy of the law as a guide for his life. But Deuteronomy is not a second law; it is an exposition of the meaning of the first law given at Horeb, which is found in sections of Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers, particularly the “Ten Words” (the “Ten Commandments”) in Exod 20:1–17. For Jews and Christians, Deuteronomy has always been an important book. The central liturgical text in Judaism—the Shema (Hebrew šĕma ʿ ; 6:4–9; cf. 11:18–20; Num 15:37–41), which contains the foremost theological truth of God’s oneness and the accompanying ethic of a total love for this one God—stems from this book. Jesus agrees with this assessment (Mark 12:29–30). But his is not just a formal agreement. He must have meditated on this book so much during his life that its fundamental themes of trust and obedience became the overarching motivation of his life. As an indication of its significance for him, he cited the book more than any other OT book. At the beginning of his ministry when he was tested in the wilderness for 40 days, he cited texts from Deuteronomy three times to defeat the tempter (Matt 4:4, 7, 10). He thus paralleled Israel’s 40-year period of testing in the OT; but by relying on the word of God, he succeeded where Israel failed.

Deuteronomy comes after an entire generation has died in the wilderness as a result of disobedience. The book powerfully renews the covenant to ancient Israel and attempts to show the Israelites the heart of the covenant. Israel is called to consider the meaning of its call and election, the blessing of Abraham, the exodus, and the imminent gift of the land. Will God’s project for the world—that Israel bless the nations through the seed of Abraham—fail? This book ultimately teaches that the greatest obstacle to this project will not be the Egyptians or the Canaanites but the human heart. And God will solve that problem.

Author and Date

The book presents Moses’ last address to a new generation of Israelites as they are about to enter the promised land in fulfillment of some of the promises to the patriarchs. It functions as Moses’ last will and testament to Israel as he prepares to die. He represents the last of the old generation that has died in the wilderness because of unbelief as he passes on the torch of faith to the new generation on the plains of Moab. Between a short introduction (1:1–5) and a brief conclusion (34:1–12), the book consists of four major sections that are largely made up of speeches looking to the past (1:6—4:43), present (4:44—28:68), and future (29:1—32:52), followed by a final benediction (33:1–29). In the second and third sections the structure is complex. Ch. 27 provides a narrative interlude before the climax of the second speech (ch. 28), indicating how the people will ratify the covenant when they enter the land of Canaan. In the third section, after the major speech (29:1—30:20), there are a number of speeches by Moses and God (ch. 31), followed by a long poem of witness against the people (32:1–43).

The ever-present Mosaic stamp on this book has testified to its authorship for generations of believers. The book essentially presents itself as a collection of speeches given by this great Israelite leader. If Moses did not speak them, then who in the history of Israel did? Even the great Moses could not have written about his own death (ch. 34), and there are many other places within the present book where an editor’s hand can be detected since Moses is written about in the third person (1:1–5; 2:10–12, 20–23; 3:9, 11, 13–14; 4:41—5:1a; 10:6–9; 27:1a, 9a, 11; 29:1–2a; 31:1, 7a, 9–10a, 14a, 14c–16a, 22–23a, 24–25, 30; 32:44–45, 48; 33:1; 34:1–4a, 5–12). Sometimes it is clear that the wording comes from a much later period, such as the assumption that the conquest by Israel is now a distant memory (2:12). Moreover, the final epitaph on Moses’ life suggests that many prophets have come and gone but none has equaled his stature (34:10–12). At the same time, these points should not detract from the important contribution of Moses in the same way that an editor of a modern book only enhances an author’s work. This is particularly the case when it is updated for another audience.

Particular Challenges

Literary Fiction

Beginning in the eighteenth century with the rise of modern biblical criticism, many scholars severed the historical bond between Moses and Deuteronomy. Stylistic comparisons linking the book with the historical section from Joshua–2 Kings and the book of Jeremiah (whose final forms are dated to the sixth century BC), as well as other factors, led to the view that Deuteronomy was produced by scribes in the late seventh century BC who “planted” it in the temple to be “discovered” by those renovating the temple (2 Kgs 22:8–20). It thus became the basis for a wide-ranging reform, aiding Josiah, the king of Judah, in his attempt to establish his nation’s independence. The book was no more than a pious forgery, supplying the literary fiction of Mosaic authorship to bolster political reform with theological authority. While many scholars would not accept the theory in this form any longer, the consensus of critical scholarship still views the book as being far removed from Mosaic times of the second millennium BC.

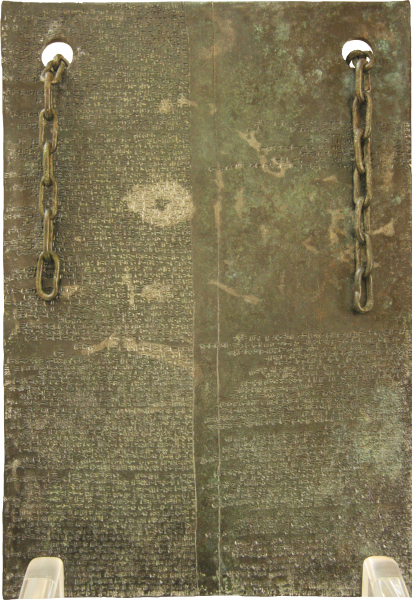

Within the last century, significant archaeological discoveries have elucidated both the covenantal structure of the book and its antiquity. The basic structure of the book parallels the genre of an ancient treaty form. Hittite treaties of the second millennium BC and Assyrian treaties from the first millennium BC exhibit many similarities to Deuteronomy. These “suzerainty” treaties were made between two parties, a sovereign and a vassal state, and consisted of six elements: (1) preamble (identifying the parties), (2) historical prologue, (3) stipulations (a list of the vassal’s obligations), (4) document deposit (an accessible copy of the treaty), (5) sanctions imposed for stipulations, and (6) witnesses to the proceedings. First-millennium treaties omit historical prologues and contain only curses for sanctions, while second-millennium pacts have historical sections and a list of blessings for loyalty. It is difficult to escape the conclusion that Deuteronomy reflects the second-millennium treaty structure: (1) preamble (1:1–5), (2) historical prologue (1:6—3:29), (3) stipulations (chs. 5–28), (4) document deposit (31:9–13), (5) sanctions—both curses and blessings (chs. 7–30), and (6) list of witnesses (31:28; 32:1). In ancient Near Eastern treaties, witnesses consisted of numerous gods, whereas the monotheism of Deuteronomy required the elimination of these “divine witnesses” and the substitution in their place of “the heavens and the earth” (31:28).

Nevertheless, Deuteronomy is more than a treaty document; it is too lengthy, and its rhetorical and urgent style is aimed mainly to persuade. Even its purely legal sections are replete with motivations. The use of treaty elements within this rhetorical tour de force points to the theological genius of the author. A genre of common political currency was modified and adapted to communicate a profound theological truth during a critical time. Israel is the servant of a divine Suzerain with obligations of love and loyalty and must remember this regularly in a public ceremony (31:10–13). The urgent, sermonic quality of the book combined with ancient treaty features point toward an ancient leader transmitting important truths to a new generation before he dies. These support the book’s claim that its author was none other than the great prophet Moses, a person uniquely familiar with all the wisdom of Egypt (Acts 7:22)—and presumably also its legal documents. The later editing of the prophet’s words shows them being used to speak to every generation.

Central Sanctuary

In line with the book’s focus on God as the center of Israel’s life and devotion, there is the call for a central worship site for offering sacrifices and tithes (ch. 12). This particular place is never identified within the book since, from its perspective, Israel has not entered the land. It is known as “the place the LORD your God will choose” (12:5; cf. 12:14). However, centralizing worship seems to conflict with other passages in the OT that describe the existence of open-air altars at other worship sites (Exod 20:24–25; Josh 8:30; 24:1, 26; Judg 2:5; 6:26; 13:16, 19; 1 Sam 7:9, 17; 9:12–14; 14:35; 2 Sam 15:7, 12, 32; 1 Kgs 18:30; 19:10, 14; Ps 74:8). Thus, many scholars understand this to be further evidence for the literary fiction of Deuteronomy: Josiah’s concern to centralize worship in Jerusalem had Mosaic roots. Of course the pious forgers were not able to erase the evidence of noncentralization from the historical record.

But the issue is fraught with complexity. Most interpreters who argue that the centralization legislation is much later also believe that “the place the LORD your God will choose” (12:5) is a coded expression for Jerusalem. Yet Deuteronomy never mentions that name, and there is provision for a sacrificial altar in Shechem (ch. 27)! Similarly, legislation in Deuteronomy assumes the construction of other altars (16:21). This coheres with earlier Pentateuchal legislation that allows for stone altars other than the bronze altar at the central sanctuary (Exod 20:24–26; 27:1–8). Thus, the central sanctuary is the exclusive gathering for national holy days and, for the most part, for the offerings of tithes and sacrifices. This central sanctuary did not have a permanent location until the temple was built in Jerusalem. It existed earlier at Shiloh (Josh 18:1; 1 Sam 1:3) and also perhaps at Bethel, Shechem (Josh 24), and Gilgal (Josh 4:18—5:12). Other altars would have been a necessity in a large and spacious land; otherwise, the practice of regular formal worship would have been a practical impossibility for most people.

In later Israelite history, some of these altars seemed to compete for centralization (Josh 22:10–34; 1 Kgs 13) or became contaminated by foreign religious practices. Thus, there is the later concern to eliminate such sanctuaries, which were often described as “high places.” Such high places became the locus of religious syncretism within the kingdom of Israel. They were also tolerated by the kings of Judah with three exceptions: Jehoshaphat (2 Chr 17:6; cf. 1 Kgs 22:43), Hezekiah (2 Kgs 18:2–4), and Josiah (2 Kgs 22:1—23:25). God’s ideal was to have one central sanctuary and one main sacrificial site, but this was hard to achieve in reality.

Place of Composition and Destination

The core of the book was first spoken on the plains of Moab, and its literary form was stored beside the ark of the covenant, which was to be placed in the central sanctuary in the land of Canaan (31:24–26). But its ultimate destination was meant to be the lives of the Israelites, written on their individual hearts, the doorposts of their homes, and their city gates throughout the land (6:6, 9). A final edition of the book, emphasizing the end of prophecy and the eschatological hope for a prophet like Moses (34:10–12), was eventually incorporated into the Genesis to Kings history.

Themes and Theology

The Unity and Centrality of God

The dominant theme of the book is that the one God, the Creator, has acted in history and called out a people, rescued them from slavery, and entered into a covenant with them, calling them to love him with all their being. All other allegiances are subordinate. The theological heart of the book is 6:4–9, the Shema, which Orthodox Jews recite every morning and evening: “Hear [Hebrew šĕma ʿ ], O Israel: The LORD our God, the LORD is one . . .”

The Unity of the People

Matching the centrality of God and the centrality of a national worship site is the oneness of the people of Israel. The gatherings for public worship at the various national festivals celebrate not only the oneness of God but also the unity of the people. The people are often depicted in all their diversity—adults, children, servants, Levites, foreigners—rejoicing before the Lord and celebrating as one people in their annual pilgrimages. The book frequently uses the Hebrew word ʾaḥ (47 times), which is a kinship term meaning “relative,” “brother,” or “fellow Israelite,” and its frequent use indicates the filial regard that the people are to express for one another. They are all members of one family, whether or not they live close to one another or know one another (cf. 22:1–3). This unity means that even the king is simply a fellow Israelite (17:20) and as family members, God’s people must be kind to one another, especially the economically destitute (ch. 15).

The Name, Word, and Image of God

Another theme in Deuteronomy is the transcendence of God. Even when God appeared in the fire on Mount Sinai (usually named “Horeb” in Deuteronomy), Israel did not see any divine form. God was audible but invisible. God came near in his words. One could not make a divine image, but one could clearly discern God’s will and presence. He was present in his words and name, which represent his character.

God places his name in his dwelling place at the central sanctuary (12:5, 11). The name is a personal identity card, indicating God’s presence and character and his stamp of ownership. To know God’s name is to know God’s character and his way of acting in the world. It is the fundamental sign of his presence. God revealed his name at the burning bush (Exod 3:12–15) and then more fully at the burning mountain (Exod 34:5–7). It is this God who has drawn near to the Israelites in the burning fire and placed his name among them. The speaking God has no man-made or artificial image. The tablets of stone on which God inscribed his words were to be transferred to human hearts not with ink but with the Holy Spirit (2 Cor 3:2). This is one way the invisible God becomes clearly visible.

Holy War

One cannot read Deuteronomy for long without encountering violence and war. What makes it worse is that these wars are divinely sanctioned (7:1–26; 20:16–18). All the Canaanites must be wiped out. Biblical interpreters have tried to address this troubling teaching in at least four ways:

1. Israel misunderstood the divine command, hearing it in the context of an often violent ancient Near Eastern culture. Thus, e.g., it would have been natural in the ancient world for people to slaughter their enemies and legitimize the violence by claiming divine sanction. There are many examples outside Israel of this feature of ancient culture. For example, Mesha, the Moabite king in the time of Omri, claimed that his god, Chemosh, commanded him to annihilate the Israelites in the town of Nebo (Moabite Stone, lines 14–16). It would have been natural, so the argument goes, for Israel to have had the same mistaken assumptions about their God and his will for their enemies. They thus confused their “cultural” will with God’s will.

2. God accommodated his commands to ancient Israel’s understanding, gradually helping his people move beyond their bloodthirsty cultural roots to a more humane level of civilization. Thus, God “got his hands dirty,” accepting the basic cultural framework of the Israelites and issuing commands that he would not otherwise give in order eventually to lead the Israelites beyond the violent wars (in which they must destroy the enemy) to the ethic of the Sermon on the Mount (in which they must love the enemy).

3. The language is more rhetoric than reality, in line with ancient Near Eastern conventions, basically emphasizing intolerance for religious compromise. After all, after ordering the destruction of the enemy populations (e.g., 7:2), the text forbids intermarriage with them (e.g., 7:3). Why would the latter command even be necessary if the former was carried out?

4. This was an act of God’s judging people who deserved it (cf. Gen 15:16). In some ways it was no different than the flood and the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah; the only difference in the case of the conquest of Canaan was that human beings were the agents of destruction.

First, while there are elements of truth in the second and third views, it is difficult to avoid the clear teaching of Deuteronomy and the rest of the Bible: God’s judgment is a reality. In many ways what God commanded Israel to do was no different than what other nations had done when God guided them to execute his judgment upon other groups by conquering them (2:10–12, 20–23).

Second, the text constantly refers to the abominations of the Canaanites and mentions some of their barbaric practices (12:31; 18:9–12; cf. Gen 15:16).

Third, the Israelites were to be just as ruthless in eliminating religious apostates from their own community (13:12–17) as they were in destroying apostate nations. At the conquest of Jericho, a Canaanite woman and her family were spared destruction because of faith in the Lord, while an Israelite man and his family were destroyed for breaking the covenant (Josh 6:17; 7:18–26). The Canaanite woman, Rahab, was included in the genealogy of Jesus, whose purpose in coming was ultimately to be a worldwide blessing. Rahab is but one example of people spared divine judgment because of faith. There were probably others (cf. Josh 9; Judg 1:23–28).

Fourth, the wars of military conquest were limited to the land of Canaan, where God’s holy presence was to dwell, and they were one-time actions, foreshadowing final judgment when the world will be cleansed from all evil (2 Pet 3:11–14; Rev 21:1–8). In the meantime, the constant concern is that Israelite faith would be contaminated and destroyed if Canaanite idolatry were allowed to coexist with it. Without that faith intact, God’s salvation-project—to bless the nations through Israel—would be in jeopardy (Gen 12:3). Thus, in a very real sense, God had to be against the Canaanites in a particular, limited time in order to be for them in the long run.

Fifth, the covenantal context of these wars is striking. After a city was defeated in the wars of conquest, the enemy king’s corpse was taken outside the city and hung on a tree until sundown, thus indicating that the king and people were under the curse of judgment for violating God’s law (21:22–23; Josh 8:29; 10:26–27). In the fullness of time, in order that the entire world would be blessed, the holy Son of God bore the judgment of God’s curse by being crucified outside the holy city, hanging upon a tree until sundown. With his resurrection a new world has begun in which everyone by faith in the “cursed” Messiah might be blessed, for “now is the day of salvation” for universal blessing (2 Cor 6:2). The Valley of Achor has now become “a door of hope” (Hos 2:15). But for those who remain intransigent in their sin and evil, a judgment day is coming compared to which the Canaanite judgment is a pale imitation (2 Thess 2:7–10).

Sixth, because of this new world order that has begun, Christians in the meantime are called to engage in spiritual warfare, fighting the principalities and powers of the old age that remain hostile to God’s will through spiritual weapons and not material swords and spears (Eph 6:10–20). They are called to go not into Canaan but into all the world with the message of Christ (Matt 28:18–20). Their weapons are not “the weapons of the world” (2 Cor 10:4); the latter have been transformed into pruning hooks and plowshares with the coming of the Messiah (Isa 2:1–5). The spiritual weapons of prayer, the word of God, faith, and proclamation of the gospel attack every spiritual stronghold that would set itself up against the knowledge of God (2 Cor 10:5) until the kingdom of God has finally come.

The Nature of the Law and Its Fundamental Spirit

Most of the legislation in Deuteronomy applies the Ten Commandments to the new conditions of Israelite settlement in the land of Canaan. The “Ten Words” that the Lord directly spoke are the fundamental moral directives for this new life upon which everything is based. In terms of modern legal systems, the Ten Commandments function like the constitution of ancient Israel: all other laws apply this policy to the situations in ancient Israel. As a constitution reflects the basic values of the nation that creates it, the constitution of Israel reflects God’s character. What kind of God would forbid other gods and idols? A God committed to truth and reality. What kind of God would forbid violating his name and identity? A God committed to his own holiness. What kind of God would command a Sabbath law? A God committed to the re-creation of his world and the liberty and rest of his creatures. While there certainly are exceptions, the Ten Commandments provide a basic, general framework for the organization of the many laws in chs. 12–26. The initial two commandments, which forbid the worship of other gods and idolatry, find expression in the command to destroy Canaanite sanctuaries throughout the land (12:1–3). The third commandment, which forbids violating the holiness of the name of God, is reflected in the concern for the Israelites to live holy lives (ch. 14), particularly in their distinct diet. The fourth commandment, the command to observe the Sabbath, is expressed in the command to observe the sabbatical year in order to provide economic relief for the poor (ch. 15). Thus, the Ten Commandments consist of broad principles, not narrow laws, and their interpretation should not be restricted to a wooden literalism. Consequently the sixth commandment, which forbids murder, can result in a building code concerned for safety (22:8), and the seventh commandment, which forbids adultery, also addresses sexual purity, even before marriage (22:13–21). Deuteronomic law, like biblical law in the Pentateuch and ancient Near Eastern law, is exemplary rather than comprehensive, but this exemplary nature points to its wide-ranging application. Such examples show the concern for a life of total obedience aimed at the transformation of the heart.

This sermon on the plains of Moab demonstrates the implications of the covenant at Mount Sinai and may be compared to the Sermon on the Mount. Like Jesus’ sermon, it takes the words of God delivered on Mount Sinai and shows what obedience to God should look like in the new land of Canaan. More than any other book in the OT, Deuteronomy expresses the demand for total obedience to the divine will. It indicates that the first commandment is not just negatively a matter of not worshiping other gods but is positively a matter of loving the one, true God with everything in one’s being. This is impossible without divine help.

The Importance of Decision: Now and in the Future

The urgent need for the present generation to make a decision for the Lord is one of the main concerns in the book. Repeatedly (48 times) the word “today” sounds in the ears of the people as they stand on the plains of Moab. The word calls for decision now—not yesterday, not tomorrow, but today! The previous generation failed to obey, and they ended up wandering in the wilderness for 40 years before they all perished (1:41–46; 2:14–15). The situation is urgent. Israel must obey today!

Similarly, the revelation of God cannot be confined to the past. Even though most of the generation on the plains of Moab was not at Horeb to witness the theophany, God made the covenant with them and not with their parents (5:2–3), speaking with them “face to face” (5:4). The time between the moment then and the moment now has been erased as the people hear the word of God directly and immediately. The same experience must also be communicated to the next generation (4:9–10, 40; 5:29; 6:2; 11:19, 21; 12:25, 28; 29:11, 22, 29; 30:2, 19; 31:13; 32:46). The people must embody the covenant in rituals and habits that will be such a part of ordinary life that their children will naturally ask about the meaning of such things (6:4–9, 20). When this opportunity arises, the parents will respond with “gospel”: “We were slaves of Pharaoh in Egypt, but the LORD brought us out of Egypt with a mighty hand . . . The LORD commanded us to obey all these decrees and to fear the LORD our God” (6:21–24). Faith is not just a privatized concern for individual salvation but also involves an intentional decision to shape future generations.

The Eschatological Hope and a New Covenant

As Moses presides over covenant renewal, he is aware of the eventual apostasy of his people. Israel will be a witness to the nations that human beings—despite the best advantages—cannot do the will of God without God’s help (4:25–28; 29:22–28; 30:1–10; 31:14–29; 32:15–38). Deuteronomy bears witness to the hope that the Lord will someday do for Israel what it could not do for itself: circumcise the peoples’ hearts so that keeping the law was as natural as breathing (30:6; cf. 10:16; 30:14). The prophets were influenced by this hope and called it the new covenant—a covenant by which the Lord would forgive the sins of his people and write the law on their hearts (Jer 31:31–34; cf. Isa 54–55). Paul said that such a day finally arrived in Christ, who perfectly kept the law while suffering its curses—not for himself but for covenant-breakers. Now when such sinners confess Jesus as Lord, they are fully justified by God and empowered to do his will (Rom 10:6–10; cf. Deut 30:11–14).

Occasion and Purpose

The book addresses a new generation of Israelites on the verge of entering the land God promised to the patriarchs. Moses, as the last of the previous generation (with the exception of Caleb and Joshua), is presenting his final words to the new generation before he dies. His speeches aim to interpret the law given at Horeb for the new generation, and as such there is an air of dire urgency and importance. The previous generation failed because they did not believe the divine word. Though the book has often been seen as a covenant renewal document, it also points forward to an ultimate resolution of the problem of evil in the human heart (30:1–14). God promised the seeds of such a solution long before in the Abrahamic covenant (4:31). The book’s primary purpose as the word of God is to reveal clearly the unflinching demands of a holy God and his provision of radical grace. Consequently, the book inspired far-reaching renewal in the later history of Israel during the reigns of Jehoshaphat, Hezekiah, and Josiah, as well as in the later history of the church.

Genre and Structure

The hortatory, repetitive nature of the book, with its core of legislation (chs. 12–26) and treaty elements, has been organized into six sections, the heart of which contains a number of motivational speeches (or “sermons”), the aim of which is to renew the covenant at Horeb. Each speech is introduced with a formal rubric (1:1–5; 4:44–49; 29:1; 33:1), and the speeches move in staircase-like fashion, finally climaxing in a pronouncement of blessing on the tribes (33:2–29). There is a narrative interlude at the end of the second speech (ch. 27), followed by a list of blessings and curses (ch. 28).

Section 1 (1:1–5) is a short introduction to the book. Section 2 begins with an initial speech that recapitulates the history from the covenant made at Horeb until the present time with Israel now on the doorstep of Canaan (1:6—3:29) and concludes with the implications of the revelation at Horeb (4:1–43).

Section 3 begins with the second speech (4:44—26:19; 28:1–68), which resumes the last main point of the first speech (the revelation at the mountain) and hammers home repeatedly the significance of the Ten Commandments and the importance of obedience (5:1—11:32). Then it applies the Ten Commandments to the life of the nation (chs. 12–26) along with the consequences of blessings for obedience and curses for disobedience (ch. 28). Ch. 27 briefly interrupts the speech with a narrative in order to provide instructions for a covenant ratification ceremony when Israel enters the land.

Section 4 begins with the third speech (29:1—30:20). Moses addresses the last main point of the second speech—the problem of the inevitability of the curses for disobedience—and promises eschatological hope, “the secret things” (29:29), as an ultimate solution (30:1–10). Ch. 31 introduces Section 5 with a narrative depicting the transition of leadership to Joshua, which is followed by a prediction of Israel’s future rebellion and a song of witness against Israel. This song provides an entire mini-history of Israel in its election, judgment, and final salvation, and it reinforces Israel’s future hope (32:1–47). This is followed by a final address by God to Moses (32:48–52).

Section 6, the last section, reinforces the final note of blessing predicted for Israel’s future in the previous two sections; that blessing is now elaborated and extended to all the tribes, envisioned now throughout the land of Canaan (33:1–29). As Jacob delivered a deathbed benediction to his sons (Gen 49), so Moses does the same for Israel. An epilogue (ch. 34) describes Moses’ final vision of the land before his death and burial and then notes the transition of leadership to Joshua.

The Application of the Ten Commandments to Life in the Land of Canaan

After presenting the fundamental call to allegiance to the one God in his second address to the Israelites, Moses then delivers the core of the speech in chs. 12–26. While there are some significant exceptions, the laws found here are not arranged haphazardly but generally reflect the order of the Ten Commandments.

These decrees and laws creatively apply the fundamental values embodied in the Ten Commands in sermonic form with many motivations. For example, one of the first concerns for the application of the Sabbath law is relief from debt slavery during the sabbatical year (ch. 15), and the command to honor parents expresses concern for the right attitude with regard to authority in general (16:18—18:22). Moses is thus interpreting the law—opening it up instead of shutting down its relevance through a woodenly literal understanding—and trying to persuade the Israelites to keep the commands for various reasons. They are ultimately words of “life” (32:47). The Ten Commandments are not so much a law code as they are broad principles that underlie the decrees and laws Moses is about to expound to the people in chs. 12–26. Moreover, these decrees and laws are far from exhaustive; they are paradigms of how to interpret the Ten Commandments. This requires wisdom, which is what the law is all about (4:6–8).

Canonicity

There has never been any doubt about the canonicity of Deuteronomy. Many OT scholars argue that the process of canonization began with Deuteronomy. Its concepts were recognized as authoritative for the historical books; and from its inception as the “Book of the Law,” it was placed alongside the “Ten Words” by the ark of the covenant. With the “Ten Words” Deuteronomy formed a seminal canon that would evolve to include more and more books until the canon was finally closed. The first evidence of a canonical formula in the Bible occurs in Deuteronomy (4:2; 12:32), and the last time it occurs in Scripture is, appropriately, at the end of the Bible (Rev 22:18–19).

Outline

I. Introduction (1:1–5)

II. The First Speech: Keep the Law (1:6—4:43)

A. The Command to Leave Horeb (1:6–8)

B. The Appointment of Leaders (1:9–18)

C. Spies Sent Out (1:19–25)

D. Rebellion Against the Lord (1:26–46)

E. Wanderings in the Wilderness (2:1–23)

F. Defeat of Sihon King of Heshbon (2:24–37)

G. Defeat of Og King of Bashan (3:1–11)

H. Division of the Land (3:12–20)

I. Moses Forbidden to Cross the Jordan (3:21–29)

J. Obedience Commanded (4:1–14)

K. Idolatry Forbidden (4:15–31)

L. The Lord Is God (4:32–40)

M. Cities of Refuge (4:41–43)

III. The Second Speech: The First Priority Is Absolute Allegiance to the Lord (4:44—28:68)

A. Introduction to the Law (4:44–49)

B. The Ten Commandments (5:1–33)

C. Love the Lord Your God (6:1–25)

D. Driving Out the Nations (7:1–26)

E. Do Not Forget the Lord (8:1–20)

F. Not Because of Israel’s Righteousness (9:1–6)

G. The Golden Calf (9:7–29)

H. Tablets Like the First Ones (10:1–11)

I. Fear the Lord (10:12–22)

J. Love and Obey the Lord (11:1–32)

K. The One Place of Worship (12:1–32)

L. Worshiping Other Gods (13:1–18)

M. Holiness (14:1–29)

1. Clean and Unclean Food (14:1–21)

2. Tithes (14:22–29)

N. The Year for Canceling Debts (15:1–11)

O. Freeing Servants (15:12–18)

P. The Firstborn Animals (15:19–23)

Q. The Passover (16:1–8)

R. The Festival of Weeks (16:9–12)

S. The Festival of Tabernacles (16:13–17)

T. Judges (16:18–20)

U. Worshiping Other Gods (16:21—17:7)

V. Law Courts (17:8–13)

W. The King (17:14–20)

X. Offerings for Priests and Levites (18:1–8)

Y. Occult Practices (18:9–13)

Z. The Prophet (18:14–22)

AA. Cities of Refuge (19:1–14)

BB. Witnesses (19:15–21)

CC. Going to War (20:1–20)

DD. Atonement for an Unsolved Murder (21:1–9)

EE. Marrying a Captive Woman (21:10–14)

FF. The Right of the Firstborn (21:15–17)

GG. A Rebellious Son (21:18–21)

HH. Various Laws (21:22—22:12)

II. Marital and Spiritual Fidelity (22:13—23:14)

1. Marriage Violations (22:13–30)

2. Exclusion From the Assembly (23:1–8)

3. Uncleanness in the Camp (23:9–14)

JJ. Miscellaneous Laws (23:15—25:19)

KK. Firstfruits and Tithes (26:1–15)

LL. Follow the Lord’s Commands (26:16–19)

MM. The Altar on Mount Ebal (27:1–8)

NN. Curses From Mount Ebal (27:9–26)

OO. Blessings and Curses (28:1–68)

1. Blessings for Obedience (28:1–14)

2. Curses for Disobedience (28:15–68)

IV. The Third Speech: Covenant Ratification, Failure, and Future Hope (29:1—30:20)

A. Renewal of the Covenant (29:1–29)

B. Prosperity After Turning to the Lord (30:1–10)

C. The Offer of Life or Death (30:11–20)

V. Planning for the Future (31:1—32:52)

A. Joshua to Succeed Moses (31:1–8)

B. Public Reading of the Law (31:9–13)

C. Israel’s Rebellion Predicted (31:14–29)

D. The Song of Moses (31:30—32:47)

E. Moses to Die on Mount Nebo (32:48–52)

VI. Benediction and Burial (33:1—34:12)

A. Moses Blesses the Tribes (33:1–29)

B. The Death of Moses (34:1–12)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()