Richard S. Hess

The Historical Books (Joshua–Esther) describe God’s work among his people. They enable us to understand most of the OT’s chronological order. These books outline the major events of Israel’s history from its entrance into the land of Canaan until the end of the monarchy and the return of the Jews and rebuilding of the Jewish province in Israel. These books do not focus on a collection of facts. Instead, they present God’s dealings with his people and their leaders.

The Story of God’s Grace and Human Response

Joshua, Judges, Ruth

The book of Joshua describes God’s gift of land to Israel as they enter the land of Canaan to possess it. The grace God pours out upon his people enables great victories in the promised land. The covenantal promises that Israel gives God at the end of Joshua seem to disappear in Judges. There the people of God engage in a constant struggle with their enemies as they repeatedly forget God’s faithfulness. Then they reach such a desperate state that they have no other place to turn other than back to the true God. The love story of Ruth and Boaz balances the brutality and slaughter with which the book of Judges concludes. Ruth demonstrates that God has not forgotten his people and that non-Israelites remain welcome in the covenant.

1-2 Samuel

If the people become unfaithful, so do their leaders. The books of Samuel begin with the faithfulness of Hannah in contrast to the sins of the house of the priest Eli. God calls Samuel to be a prophet and a priest, but the people want a king like all the other nations. God commands Samuel to anoint Saul as king, but God later rejects unfaithful Saul and appoints David as king. God gives David an everlasting dynasty, but King David cannot control his desire for another man’s wife (2 Sam 11–12). The sin of murder and adultery that David introduces into his family continues to affect his children.

1-2 Kings, 1-2 Chronicles, Ezra, Nehemiah, Esther

1-2 Kings display further examples of God’s faithfulness among his people, preserving them in the midst of threats to destroy them. Nevertheless, the kings and the people depart from God’s teaching and serve other gods and goddesses. In the end God allows foreign nations to conquer the kingdoms of Israel and Judah. These foreign nations deport the people, but the promise of the faithful God to preserve his people goes with them into exile. There God’s compassion preserves the Jewish people despite attempts by powerful enemies to destroy them. This is illustrated in the book of Esther, a story in which God, though not mentioned by name in the book, works salvation for his people. Ezra and Nehemiah describe how a scribe and a governor lead the community of exiles who return to Jerusalem. They rebuild the walls and reaffirm the covenant God gave them. 1-2 Chronicles survey the great story of God’s work with his people, especially with the people of the southern kingdom of Judah.

Books of History

The term “Historical Books” invites us to ask, “What are the books? What is history?” In ancient Israel each of these “books” would actually have been written on a scroll. These books appear in the Christian OT in the general chronological order of their content: Joshua, Judges, Ruth, 1-2 Samuel, 1-2 Kings, 1-2 Chronicles, Ezra, Nehemiah, and Esther. In the Hebrew Bible (as preserved in Judaism), Joshua, Judges, 1-2 Samuel, and 1-2 Kings constitute the Former Prophets. This section immediately follows the Torah (Genesis–Deuteronomy), as in Christian Bibles, and precedes Isaiah and the other prophetic books that constitute the Latter Prophets. The remaining historical books appear in the final section of the Hebrew Bible, called the Writings, with 1-2 Chronicles closing the Jewish Bible.

Although many books contain historic materials, the Historical Books focus on history by presenting it in narrative form. In conveying the story of God’s acts, they also use poetry (Judg 5), prophecy (2 Kgs 19), building descriptions (1 Kgs 6–8), prayers (1 Kgs 8; Neh 9), royal decrees (Ezra 6:3–12), boundary descriptions (Josh 13–19), covenants (Josh 24), and genealogies (1 Chr 1–9). Most often, however, they tell stories that describe God at work among his people. The form of language used to convey great examples of God’s direct involvement to deliver his people (Josh 10; 2 Kgs 18–20; 2 Chr 20) is not different from that used to record history without the extraordinary miraculous intervention of God (Ruth; Ezra; Nehemiah). The two types of accounts flow together as different ways in which the same God works with his people to bring about his purposes. Nor does the narrative show privilege to those of high social status. Humble foreigners such as Rahab the Canaanite (Josh 2), Ruth the Moabite (Ruth 1), and the woman of Sidon (1 Kgs 17) play crucial roles in the salvation of Israel. They appear alongside the line of its divinely chosen kings as well as priestly and prophetic leaders.

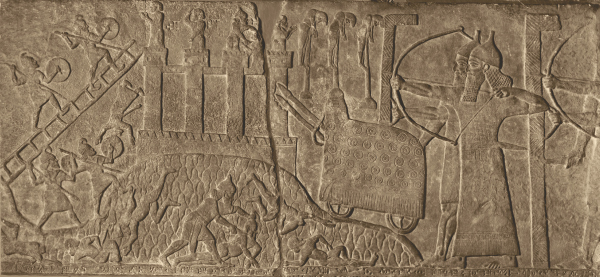

Historical writing is always selective. For this reason, we may read two well-written histories that are both factually accurate, yet they portray the same events from different perspectives. One example of this can be found in the accounts of the invasion of Judah by the Assyrian king Sennacherib when Hezekiah was king in Jerusalem. Much of the same information in 2 Kgs 18–19 (see the parallel account in Isa 36–37) is repeated in 2 Chr 32. However, 2 Kgs 18:13–16 begins the story by making clear that Hezekiah paid tribute to Sennacherib, while 2 Chr 32:22–23 concludes the story with many people bringing offerings to God in Jerusalem and giving honor to Hezekiah because the Lord delivered his people. While 2 Kings emphasizes Hezekiah’s innocence by recording that Hezekiah gave Sennacherib what he demanded, 2 Chronicles focuses on how much God did and how the people responded to God with worship. Much of the account in 2 Kings concerns the prophet Isaiah’s involvement, while only one verse in 2 Chronicles (2 Chr 32:20) mentions Isaiah. The two accounts both present history, but they provide different theological emphases and concerns. Both emphasize how Hezekiah trusted in God and how God miraculously defeated Sennacherib’s army.

A second example in this same context mentions how Sennacherib’s own sons killed him while he was worshiping in the temple of his god (2 Kgs 19:36–37; 2 Chr 32:21). As Assyrian records show, this murder occurred 20 years after Sennacherib invaded Judah. The Bible does not indicate this length of time because it is not important to its purpose. Instead, it demonstrates the disgraceful end of the king who mocked God’s ability to defend his people. Given its selective nature, accounts of history should be read with special attention to the author’s purpose. In the historical books of the Bible, the focus remains on God’s relationship with his people and the outworking of his covenants with them.

Covenant Themes

God established covenants with Abraham, with the people of Israel, and with David. Each of these covenants defines aspects of how God will act in Israel’s history in accordance with Israel’s beliefs and behavior. The Historical Books maintain a special concern for the events in Israel in light of the covenants and God’s work through them.

The Covenant With Abraham

God promised Abraham (1) a great nation, (2) a land, and (3) a means by which Abraham and his descendants would bless all peoples of the earth (Gen 12:1–3, 7). By the time we encounter Israel in the book of Joshua, the people are becoming a great nation. This first book among the Historical Books establishes how Israel acquires some of the land. The possession of the promised land remains precarious in Judges, which describes many warring peoples seeking to destroy Israel (and ultimately the nation turns against itself in the civil war of Judg 19–21). This uncertainty continues in 1 Samuel as the Philistines threaten to remove the tribes from their land. However, the wars of David (2 Sam 5–10) establish the city of Jerusalem and the capital of a nation that stretches to the limits of that which God had promised to Abraham (Gen 15:18–21) Nevertheless, the faithlessness of the people of Israel prevents them from enjoying this prosperity for more than a generation. When Solomon dies, his son Rehoboam makes unwise choices that divide the kingdom and plunge much of it into the worship of other gods (1 Kgs 12–13). The varying fortunes of the northern kingdom of Israel and the southern kingdom of Judah exhibit the differences in attitude the Israelite people and their kings have toward their God. The destruction of the northern and southern kingdoms and the subsequent deportations of their inhabitants might suggest that God has forgotten his promise to Abraham. Instead, the promise of the return (already found in 2 Chr 36:20–23) comes to pass as the books of Ezra and Nehemiah demonstrate the faithfulness of God to increase Abraham’s descendants and secure them in the land.

The third part of the promise to Abraham is that God will bless other nations through Abraham’s descendants. The first miracle of the Historical Books occurs when God stops the Jordan River and Israel marches across on dry ground (Josh 3–4). God did this “so that all the peoples of the earth might know that the hand of the LORD is powerful” (Josh 4:24). This and the subsequent acts of God signify that the God of Israel is the true God; he alone is able to perform miracles. These actions bring many non-Israelite people into God’s kingdom: Rahab (Josh 2; 6), the Gibeonites (Josh 9), Ruth (Ruth 1–4), the queen of Sheba (1 Kgs 10; 2 Chr 9), Naaman (2 Kgs 5). Even King Cyrus (2 Chr 36:23; Ezra 1:2) recognizes the greatness of Israel’s God.

When Solomon dedicates the temple (1 Kgs 8), he describes how God’s people may look to the temple and their God and pray to find salvation and relief in various circumstances of need and distress. His prayer turns to consider those outside the family of Israel (1 Kgs 8:41–43): Solomon asks God to “do whatever the foreigner asks” (1 Kgs 8:43b) if the foreigner comes and prays toward the temple. The foreigner need not be part of the people of God. Solomon specifies the purpose of his request to God: “so that all the peoples of the earth may know your name and fear you, as do your own people Israel” (1 Kgs 8:43c). Solomon requests that God might bless the peoples of the world, just as God promised Abraham, so that they might come to know God.

The Covenant on Mount Sinai

God’s covenant with the nation of Israel provides a key to understanding major themes in the historical books. The covenant emphasizes the importance of worshiping God alone (Exod 20:3–6, 22–23; Deut 4–13). Along with many specific laws, God also promises blessings for obedience and curses for disobedience (Deut 28). After details about suffering and barrenness, the curses conclude with God’s warning that he will scatter Israel among the nations if they worship other gods (Deut 28:64–68).

God’s promise of the land, and his warnings of expulsion from it, overshadow the major events of many of the historical books. God partially fulfills his promise of the land when Joshua acquires it. The difficulties of the following generations arise from their worshiping other gods and refusing to worship the true God (Judg 2:10–15). Contrast this with Ruth’s confession (Ruth 1:16–17). The wickedness of the sons of Eli lead to the Philistine victory and the loss of the ark (1 Sam 2:12—4:18). Saul faces defeat at the hands of the Philistines as well. God’s expanding the borders of Israel signifies his blessing of David and Solomon (2 Sam 6–10; 1 Kgs 3). Nevertheless, Solomon abandons the exclusive worship of God (1 Kgs 11:4, 9), which leads to the kingdom’s division.

In the northern kingdom of Israel, every ruler turned away from God and led their people in the worship of images and other deities. In 1-2 Kings, God sent many prophets, notably Elijah and his successor Elisha, to warn the people and their leaders (1 Kgs 18:1—2 Kgs 9:13; 2 Kgs 13:14–21). The people did not turn back to God. Because they refused to worship God alone, they were deported by the Assyrians (2 Kgs 17:1–23), who then resettled the northern kingdom with people from nations who practiced various forms of false worship (2 Kgs 17:24–41). Unlike the author of Kings, the writer of Chronicles ignores most of the events that took place in the northern kingdom, focusing instead on the southern kingdom of Judah as the place of hope for restoration.

The people of the southern kingdom were also inclined to serve other gods and goddesses. However, the rise of several good kings, such as Jehoshaphat, Hezekiah, and Josiah, reignited faith in the one true God of Israel. The books of Kings and Chronicles relate how the people celebrated the Passover in the time of Josiah (2 Kgs 23:21–23; 2 Chr 35:1–19), while 2 Chr 30 records the celebration of Passover nearly a century earlier in the time of Hezekiah. These historical books relate the building of the temple and its role in the worship of the people. 1 Kgs 6–9 summarizes the details of the building of the temple as part of the larger picture of the administration and reign of King Solomon. For 1-2 Chronicles, however, it is the centerpiece of the entire account. The temple dominates the legacy David leaves his son, from the details of its construction and personnel to its dedication by Solomon (1 Chr 22—2 Chr 8). Subsequently the temple appears in Chronicles nearly 90 times as a focus for the reforms by the good kings. The temple thus symbolizes God’s presence among his people and their worship of him.

Both 2 Kgs 25:1–21 and 2 Chr 36:15–21 describe the Babylonian attack and destruction of Jerusalem and its temple as well as the deportation of much of the Jewish population. 2 Kgs 22:15–20 already explained this as God’s judgment for their worship of other gods, a judgment that was postponed but could not be prevented. 2 Chr 36 reiterates that the loss of the land came because the people broke their covenant with God and worshiped other gods.

The final verses of both 2 Kings and 2 Chronicles indicate that this was not the end of the story. A Davidic king remained, although captive (2 Kgs 25:27–30); and a new Persian king, Cyrus, released the people to return and rebuild their land and temple (2 Chr 36:22–23; Ezra 1:1). Both themes continue in Ezra and Nehemiah, with special concern given to the need for Israel to confirm its role as God’s people secure in the land he had given them and with emphasis on worshiping God alone.

The Covenant With David

2 Sam 7 describes the creation of the perpetual kingship of David and his descendants. Although the dynasties of Saul (1 Sam 9:15–17) and Jeroboam I (1 Kgs 11:34–39) might have known similar blessings, God rejected both due to the disobedience of the kings (1 Sam 13:13–14; 1 Kgs 14:7–11). God’s promise to David alone remained and endured through the reign of his son Solomon and his descendants for the duration of the southern kingdom of Judah. However, God promised to punish those successors of David who sinned (2 Sam 7:14). Thus Solomon’s sins in worshiping the gods and goddesses of the surrounding nations led to the removal of most of the kingdom from the rule of Solomon’s son Rehoboam; there remained only the tribal area of Judah and Benjamin. Nevertheless, God promised that an heir would rule in Jerusalem as a “lamp” (1 Kgs 11:36). God repeated his promise several times in the history of the kings of Judah, especially during the reigns of those who sinned against God, such as Abijah (1 Kgs 15:4) and Jehoram (2 Kgs 8:19; 2 Chr 21:7). Even faithful rulers, such as Jehoshaphat (2 Chr 20), Hezekiah (2 Kgs 18:1—19:37; 2 Chr 32:1–23), and Josiah (2 Kgs 22:1—23:30; 2 Chr 34–35), committed sins before God (Jehoshaphat: 2 Chr 20:35–37; Hezekiah: 2 Kgs 20:12–19; 2 Chr 32:25–31; Josiah: 2 Chr 35:20–24). Among the worst of the kings of Judah was Manasseh. Despite his repentance later in his life (2 Chr 33:10–16), Manasseh’s sins were so great that Josiah’s later reforms could only postpone the judgment (2 Kgs 23:26; 24:3) that included the destruction of Jerusalem and Judah, and an end to the independent reign of the Davidic kings.

Despite the sin and punishment, 1-2 Kings ends on a hopeful note: the line of David, in the person of Jehoiachin, the last surviving king of Judah, remained alive in exile, and Jehoiachin ate from the table of the king of Babylon (2 Kgs 25:27–30). If Shenazzar (1 Chr 3:18), a descendant of Jehoiachin, is the Sheshbazzar of Ezra (Ezra 1:8, 11; 5:14, 16) who served as governor after the return from exile and who laid the foundations of the new temple in Jerusalem, then the line of David continued among the leadership that returned. We know that Zerubbabel, another descendant of Jehoiachin (1 Chr 3:19), also served as governor during the early period of rebuilding the temple in Jerusalem (Ezra 2:2; 3:2, 8; 4:2–3; 5:2; Neh 7:7; 12:1, 47). It is through this line that both Matthew (Matt 1:12–16) and Luke (Luke 3:23–27) trace David’s greatest descendant: Jesus, who comes as the fulfillment of God’s covenant with David.

Chronology/Dating

For OT chronology, see Introduction to the Old Testament.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()