T. D. Alexander

The 39 books of the OT are an integral and vital part of the Christian Bible. As a unique collection of religious documents, mostly written in the first millennium BC, they comprise about 75 percent of the Bible. The OT stands on a par with the NT, being equally inspired by God and essential for Christian teaching and practice (see 2 Tim 3:14–17).

Canon of the Old Testament

Although the evidence is sparse and open to debate, on balance it seems likely that the canon (i.e., the authoritative list of books) of the OT was closed well before the time of Jesus. While some scholars contend that the library of OT books remained fluid until the latter part of the first century AD, the earliest surviving evidence suggests that the books of the OT, or the Hebrew Bible as it is sometimes called, were viewed as an authoritative collection of writings by about 150 BC at the latest. In the prologue of Ecclesiasticus (in the Apocrypha), a Greek translation of a Hebrew book known as Sirach, the translator, writing about 132 BC, refers to the OT using the following expressions: “the Law and the Prophets and the others that followed them”; “the Law and the Prophets and the other books of our ancestors”; “the Law itself, the Prophecies, and the rest of the books.” This threefold division reflects the later Jewish custom of referring to the Hebrew Bible as the Law, Prophets, and Writings. Unfortunately, no ancient texts survive to explain how the process of canonization happened and what criteria were used to determine which books should be included. The process itself may well have occurred in stages over several centuries, and individual books were probably viewed as special long before the different sections of the canon were finally closed. Although some Christian traditions hold that various other Jewish writings should be viewed as canonical, the earliest evidence, including the authoritative testimony of the NT, suggests that only those books that comprise the Hebrew Bible are divinely inspired. On the inspiration and authority of the NT, see Introduction to the New Testament.

Contents of the Old Testament

As a highly select library of religious writings, the OT has a rich variety of contents. Although we have become accustomed to viewing the books as ordered in a fixed way, the order differs in Jewish and Christian Bibles. Whereas Jewish tradition divides the OT into three sections, Christian tradition has favored four:

1. the Law, or Pentateuch: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy (see Introduction to the Pentateuch);

2. the Historical Books: Joshua, Judges, Ruth, 1 and 2 Samuel, 1 and 2 Kings, 1 and 2 Chronicles, Ezra, Nehemiah, Esther (see Introduction to the Historical Books);

3. the Wisdom and Lyrical Books: Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs (see Introduction to the Wisdom and Lyrical Books); and

4. the Prophetic Books: the Major Prophets include Isaiah, Jeremiah, Lamentations, Ezekiel, and Daniel, and the Minor Prophets include Hosea through Malachi (see Introduction to the Prophetic Books).

Old Testament Story

The Bible is built around a grand story that starts in Genesis with the divine creation of the earth and ends in Revelation by anticipating the coming of a new earth. The OT contributes to this story by explaining the origin and nature of the human predicament, which, in essence, is our alienation from God. From the early chapters of Genesis onward, the OT describes how God sets about redeeming and restoring creation after the tragic rebellion of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. Not only is God’s redemptive activity evident throughout the OT, but by pointing forward to Jesus Christ, the OT introduces the ultimate means by which the tragic consequences of human sin will be reversed.

To understand the grand story that underlies the OT, it is important to appreciate the flow of events that shape the main plot of the story. We must recognize, however, that although various OT books, especially the Wisdom and Lyrical Books, say little directly about the OT story, they complement it by addressing important theological issues. The same is partly true for most of the Prophetic Books, but their contents are usually tied more closely to the OT story.

Primeval Era

Gen 1–11 record a small number of highly significant episodes that belong to the early history of the world from creation up to about 2000 BC. These chapters describe how humanity becomes estranged from God, leading to a world dominated by violence due to the corruption of human nature. While Adam and Eve’s betrayal of God has horrific consequences for all of earth’s creatures, God promises that one of Eve’s offspring will eventually crush the head of the mysterious, but clearly evil, serpent (Gen 3:15). Gen 4–11 trace this offspring from Adam (through Seth) to Noah and then onward (through Shem) to Abraham.

Patriarchal Period

Divided by genealogies, Gen 11:27—50:26 falls into three main sections that focus chiefly on (1) Abraham (chs. 12–24), (2) Isaac and his son Jacob (chs. 25–36), and (3) Joseph (chs. 37–50). God promises Abraham, who initially is both childless and landless, that his descendants will become a great nation in the land of Canaan and that a future descendant will mediate God’s blessing to the nations of the earth. These promises link the divine redemption of humanity to a royal line descended from Abraham (cf. Matt 1:1–17). Gen 37–48 trace this potential royal line through Joseph and his son Ephraim. Anticipating later developments, Joseph’s unexpected rise to prominence in Egypt results in blessing for many nations; this foreshadows the much greater blessing that will eventually come through Jesus Christ.

Deliverance From Oppression

Moses’ birth and death frame the books of Exodus through Deuteronomy. Events move geographically from Egypt, via Mount Sinai, to the eastern bank of the Jordan River in the land of Moab.

The early chapters of Exodus recount the enslavement of the Israelites in Egypt. After God commissions him, Moses leads the Israelites out of Egypt. This involves a series of signs and wonders that emphasize God’s authority over nature. When these extraordinary events climax in the death of the Egyptian firstborn males, God spares the Israelite firstborn when the Israelites observe a special “Passover” ritual. The Passover encapsulates the process of divine salvation whereby God redeems his people from slavery and ransoms them from death in order to create a holy nation. The subsequent destruction of the Egyptian army in the “Red Sea” confirms the Lord as savior of his people.

After rescuing the Israelites, God graciously invites them to submit to him as their sole sovereign by entering into a unique covenant relationship. God places distinctive obligations upon the Israelites, the most important being the Ten Commandments (Exod 20). The covenant ratified at Mount Sinai prepares the way for God to come and dwell among the Israelites. To facilitate this, the people construct a special tabernacle in which God will reside (Exod 25–31, 35–40).

Leviticus addresses how the Israelites should maintain their newly acquired status as a holy nation. In particular, it describes the measures necessary to atone for sin, cleanse defilement, and promote holy living.

The Israelites’ journey from Mount Sinai to the land of Canaan, recorded in the book of Numbers, is marked by a series of damaging events that demonstrate their lack of trust in God. Consequently, God punishes them: they must remain in the wilderness for 40 years. Only after the adults who left Egypt die does God permit their children to enter the promised land.

According to Deuteronomy, after arriving at the eastern border of Canaan, Moses delivers a valedictory address to the Israelites, reminding them of their covenant relationship with God and summoning them to greater loyalty. Moses pronounces that God will reward them with blessing for obedience but punish them for disobedience, resulting ultimately in exile from the land of Canaan.

Taking the Land

Joshua replaces Moses as the leader of the people and brings them safely into the land of Canaan. While only the tribes of Judah, Ephraim, and Manasseh actually take possession of territory in Canaan during Joshua’s lifetime, this initial phase of occupation progresses well with God’s support.

After Joshua’s death, the Israelites enter into a period of moral and spiritual decline that results in their enemies gaining the upper hand. The book of Judges underscores how the Israelites spiral downward as they disregard their obligations to God under the Sinai covenant. Only the divine provision of Spirit-empowered leaders, traditionally known as judges, provides periods of relief. Significantly, the tribe of Ephraim, which had been privileged with leadership of the nation, rightly receives the harshest criticism for its apostasy. Ephraim’s failure to lead the people prepares the way for the establishment of a monarchy drawn from the tribe of Judah.

The Early Monarchy

The books of Samuel record how Israel moves from a tribal system of government to a monarchy. The account of the transition is complex, but it ultimately results in David from the tribe of Judah being appointed by God as the head of a dynasty that reigns from the city of Jerusalem. According to Ps 78:59–72, God chose David and Jerusalem (Zion) after rejecting Ephraim as the royal tribe and the city of Shiloh as the location of the central sanctuary.

The enthronement of David and the choice of Jerusalem as his capital city begin a process that leads to David’s son Solomon building a temple (or divine palace) that transforms Jerusalem into the earthly residence of the divine King. Unfortunately, Solomon fails to adhere to the instructions for kings that Deut 17 lays out, resulting in his kingdom being partitioned in two.

The Two Kingdoms

The unity of the Israelites shatters after the death of Solomon when only two tribes remain faithful to his son Rehoboam. The other ten tribes appoint Jeroboam, an Ephraimite, as their king. This creates two kingdoms, Israel in the north and Judah in the south. Under a succession of short-lived dynasties, the northern kingdom becomes more and more apostate. Eventually, God punishes its population when the Assyrian king Sargon II decimates the kingdom in 722 BC.

While God’s commitment to the Davidic dynasty offers some stability to the southern kingdom of Judah, it too comes under divine judgment due to the sinfulness of its monarchy and people. After a series of invasions, the Babylonians destroy Jerusalem in 586 BC, demolish the temple, and deport the Davidic monarchy into exile. These events mark the start of the Babylonian exile, a period of deep soul-searching as the people of Judah reflect on the catastrophic events that have led to their humiliation and punishment by God.

The Babylonian Exile

Although the Babylonians raze Jerusalem in 586 BC, they previously deported Judahites to Babylon in 605 BC (see Dan 1:1) and 597 BC (see note on Dan 1:2). The displacement and subjugation of Judahites creates a period of uncertainty for the exiles as they contemplate the theological significance of these events. Little survived of all that God did for them in the past. In spite of this, prophets spoke words of comfort and promised restoration to those in exile.

The Restoration

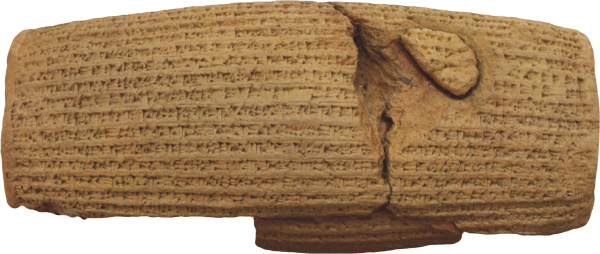

When the Babylonian Empire falls to the Persians in 539 BC, the conquering king, Cyrus the Great (559–530 BC), permits Judahite exiles to return to Jerusalem in order to reconstruct the temple. The work is eventually completed in 516 or 515 BC (Ezra 1–6; see note on Ezra 4:4). Although the returning exiles lack the resources to replicate the earlier temple, the process of restoration reassures the people that God has not abandoned them completely. Subsequently, the walls of Jerusalem are repaired under the guidance of Ezra (from 458 BC) and Nehemiah (from 445 BC). With the temple and city restored, the people are encouraged to anticipate the reinstatement of the Davidic monarchy. This, however, remains unfulfilled during the OT period. What the OT anticipates, the NT brings to fulfillment with the coming of Jesus Christ.

While the grand story of the OT moves through a series of distinctive stages, these stages are closely linked to one another as God’s plan of redemption unfolds. From the Garden of Eden to the return of the exiles from Babylon, God is at work, seeking to restore to himself an alienated humanity and to reclaim the earth from the powers of evil. In all of this, the OT prepares for events that come to fulfillment in Jesus Christ. With good reason the NT cannot be fully understood without an intimate knowledge of the OT.

Text of the Old Testament

With the modern proliferation of English Bibles, it is easy to forget that in the time of Jesus a copy of the Hebrew Bible consisted of numerous scrolls, each handwritten by a copyist. Although between the second and sixth centuries AD codices (i.e., book forms) gradually replaced scrolls, all biblical texts continued to be copied by hand. Only with the invention of the printing press in the mid-fifteenth century AD did it become possible to mass-produce identical copies of the Bible.

Not surprisingly, over a period of at least 1,500 years, copyists occasionally made minor errors as they produced new copies of biblical books one at a time. Even the best of scribes could make mistakes. Since no original manuscripts existed by which later manuscripts could be corrected, scribes replicated errors each time they made new copies. Consequently, few surviving manuscripts are completely identical. By identifying and rectifying scribal errors, modern scholars attempt to reconstruct the earliest text of the OT. This is a highly specialized field of study that relies heavily on gleaning information from the somewhat disparate manuscripts that have survived.

Before 1947, the oldest known manuscripts of the Hebrew OT were the Codex Cairensis (AD 895/96), the Aleppo Codex (ca. AD 925) and the Codex Leningradensis (AD 1008/09). With the unexpected discovery in 1947 of ancient scrolls in caves near Khirbet Qumran on the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea, scholars gained access to the remains of over 200 biblical scrolls copied between ca. 250 BC and AD 70. Among the first scrolls discovered at Qumran were a complete manuscript and a partial manuscript of the text of Isaiah in Hebrew.

Regrettably, due to the fragmentary nature of the surviving scrolls, the evidence from Qumran is not complete. Nevertheless, the scrolls confirm that the medieval codices preserve accurately the text of the Hebrew Bible. When the book of Isaiah in the medieval codices was compared with the manuscripts from Qumran, scholars concluded that only a dozen or so copyist errors need to be removed from the medieval text of Isaiah. Almost all of these changes involve correcting only one or two letters in Hebrew.

In addition to relying on the Dead Sea Scrolls, experts on OT manuscripts compare early translations of the Hebrew OT into other languages (e.g., Aramaic, Greek, Syriac). Some of these date to at least the third century BC, although only later copies have survived. The earliest and almost complete Greek translation of the OT is the fourth-century AD Codex Vaticanus. Unfortunately, the quality of translation varies among the different OT books.

Early Aramaic translations of the OT became necessary because more and more Jews spoke Aramaic as their first language. In the OT itself, half of the book of Daniel is written in Aramaic rather than Hebrew. Unfortunately, the surviving Aramaic translations tend to be paraphrases enhanced with interpretative comments. For this reason they offer only limited help in reconstructing the earliest text of the Hebrew Bible.

Although textual critics continue to explore the process by which the books of the OT were preserved and translated, we may, with a high degree of confidence, be certain that our English Bibles, allowing for translation, accurately reflect the original text of the biblical books.

Reading the Old Testament

For most people the OT is distant geographically, historically, linguistically, and culturally. Some or all of these factors may present major barriers to how modern readers understand the OT.

1. Geographic distance. The OT books are located in the world of the Middle East; they deal with events that took place in the countries that we now refer to as Israel-Palestine, Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Turkey, and Iraq. The geography of the region impacts what we read. For example, harvest time for cereal crops occurs in the spring or early summer. The semi-arid nature of parts of this region means that references to rain are often positive.

2. Historical distance. The writing of all of the OT originates before the time of Christ. The world was a very different place then.

3. Linguistic distance. Almost all of the OT was composed in Hebrew, with a few passages in Aramaic. While modern English translations enable us to comprehend what the writers were saying, we should never forget that no translation can convey fully and accurately all the nuances of the original language. Resources like this study Bible are often helpful in addressing this issue.

4. Cultural distance. The OT frequently addresses situations far removed from the lifestyle of modern societies. When we read OT texts, we need to interpret them in the light of the customs and practices that existed in the past. We must be careful not to read the text against the background of our own culture.

Reading the OT is more alien than most people suppose. If we are to make sense of it, we need to overcome the distance that exists between it and us.

Importance of the Old Testament

History itself confirms the importance of the OT. In spite of fierce criticism from opponents, few documents can rival its prominence and popularity throughout the centuries. Three factors may begin to account for this.

1. The OT recounts a remarkable story that uniquely explains life as we experience it. Offering a very realistic view of human nature and society, warts and all, it provides an unexpected explanation for humanity’s predicament. Most of all, it offers hope by reimagining a very different kind of world and by pointing readers to the God-given solution.

2. The OT has the potential to transform lives. It contains a wealth of moral teaching. It shapes our lives by its moral instructions and stories.

3. Most important, the OT provides unique insights into the nature of God. The books of the OT variously focus on the divine-human experience through stories, reports of divine messages given to earlier generations, songs of worship, and prayers. This God-orientated dimension causes the OT, alongside the NT, to transcend all other literature.

Chronology/Dating

Sometimes we can identify the events of the Bible with other events outside of the Bible and correlate those with known dates. For example, the Assyrian records of kings mention an eclipse in 763 BC, and the OT also mentions those kings. This process of correlating events yields exact dates, BC and AD. On this basis, scholars generally agree on the dating scheme for events from the time of David and Solomon onward, and we provide a single timeline for them. However, there exist two sets of dates for earlier events. These dates depend largely on how one interprets the dating scheme in the book of Judges and when one dates Israel’s exodus from Egypt. We provide both options here.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()