Douglas J. Moo

“New Testament” is the name given to the collection of 27 books that comprise the second part of the Christian Bible. “Testament” is the English equivalent of the Latin testamentum, which translates the Greek diathēkē (Hebrew berit). The Bible uses this Greek word in a rather technical sense to designate the “covenants” that God enters into with his people. In a covenant, God pledges to act on behalf of his people in certain ways, and his people, in turn, commit themselves to respond to God as he requires. Although the Bible refers to several covenants, it also suggests the idea of two basic covenants. God, through the prophet Jeremiah, contrasts the “covenant” he entered into with Israel when he brought them out of Egypt with a “new covenant” (Jer 31:31–32; see Heb 8:8–9). The sacrifice of Jesus on the cross enacts this new covenant: in Jesus’ words over the cup at the Last Supper, he calls the cup “the new covenant in my blood” (Luke 22:20). The extension of covenant language to a collection of books that describes the covenant has roots in the NT itself: the apostle Paul refers to reading “the old covenant” (2 Cor 3:14; cf. “new covenant” in 2 Cor 3:6). Building on these biblical texts, Christians were referring to the work of God in history in terms of two covenants by the end of the second century AD. Applying this language to the two collections of books that Christians recognized as inspired and authoritative Scripture was a natural step.

The Two-Testament Shape of the Bible

The two-testament form of our Bibles reflects the two basic stages in the unfolding of God’s grand program of redemption. The OT tells the story of creation, the fall into sin, and God’s inauguration of his single plan to conquer the evil that invaded his good creation and to reassert his sovereignty over the entire cosmos. God hints at his plan immediately after the fall (Gen 3:15) and sets it into motion by entering into a covenant with Abraham. God promises that he will establish Abraham’s many descendants in a land of their own and that he will use Abraham and his descendants to bless the world. Those descendants are the people of Israel. God renews his covenant with Israel, promising them that they will live securely and prosperously in the land he will give them as long as they turn their hearts to the Lord and obey his law. But despite the many blessings God bestows on Israel, the people prove again and again to be faithless, lapsing into idolatry and refusing to obey God’s law. God therefore visits his people with the judgment that he had threatened when he first gave the law: he uses pagan nations to force the people from their land, sending them into exile. Yet in the midst of his peoples’ unfaithfulness, God proves himself to be both faithful and gracious, promising to bring the people back to their land and to change the hearts of his people so that they will be fully able to obey him and bring glory to his name. This deliverance is often associated with a redeemer figure, often portrayed as a warrior-king like David. God promises to use this redeemer figure to punish Israel’s enemies, save the people of Israel, and extend God’s blessing to the nations.

The NT is the story of how God fulfills this promise of salvation. Jesus is the redeemer whom God had promised. Jesus is the “Christ,” the “anointed one,” or “Messiah.” Yet the program of redemption does not initially take the shape that most Jews in Jesus’ day were expecting. While Jesus manifested his power in miraculous works, he did not gather the armies of Israel to battle the pagan nations oppressing the people. Instead, he allowed himself to be condemned and put to death by those pagans. Yet this startling turn in the history of redemption was, in fact, anticipated in many OT passages. God’s raising Jesus from the dead announced to the world that Jesus was, in fact, God’s “anointed one,” the one through whom God was bringing salvation to his people. Moreover, the Christ who went humbly to his death is also the Christ who will return again in glory to judge the world and fully establish God’s sovereignty over all creation. These two “comings” of Jesus provide the two fundamental linchpins of the NT story. Jesus’ first coming inaugurates the “last days,” the time when God fulfills his promises of judgment and salvation. Jesus’ second coming will culminate the end-time work of redemption. Much of the NT is devoted to helping believers understand the nature of this time in which they live: “already” brought into God’s kingdom by the work of Christ, but “not yet” enjoying the full benefits of God’s redemptive program.

One of the most significant storylines in the NT is a redefinition of the people of God. In the OT, God’s people are by and large identified by their descent from Abraham: the people of Israel. To be sure, the OT itself plainly indicates that God’s people cannot ultimately be confined to Israel. Yet the NT announces a new and revolutionary step in this direction: God’s people are now defined by their relationship to Christ, the descendant of Abraham. Only Jews who place their faith in Christ are the true people of God; and Gentiles, through that same faith, can now join believing Jews as full and equal members of God’s people. A “new covenant” has been inaugurated through the redemption won by Christ and sealed by the pouring out of God’s Spirit with new power on all his people.

The two-testament format of our Bibles therefore reflects the contrast between “promise” and “fulfillment” that is the central storyline of the story of the Bible. This story is one continuous story that falls into two basic parts; there is both continuity and discontinuity. We err if we do not recognize the fundamental shift in salvation history that Christ’s coming created; as Jesus himself put it, he has brought “new wine” that cannot be confined in the “old wineskins” (Mark 2:22). But we also err if we fail to recognize that the two stages of salvation history are part of one continuous story, a single plan of God to reclaim his creation: two “testaments” but one Bible.

The Books of the New Testament

Gospels

The first four books of the NT are named “Gospels.” The word “gospel” comes from the Old English god spell, a phrase that means “good news.” In the NT this word never refers to a book; it denotes the coming of Christ and the message about him (e.g., Mark 1:1 [“good news”]; Rom 1:16; 1 Thess 1:5). By the early second century, however, Christians were calling the books that recorded the life of Jesus “Gospels.” But the original application of the word was not left behind. The titles of our Gospels take the form “[the Gospel] according to Matthew,” etc.—that is, the story of the good news as related by Matthew, etc. (The titles are abbreviated in the NIV.) While our Gospels are not biographies in the modern sense, their obvious focus on the life and significance of one person, Jesus Christ, suggests that they fit comfortably in the ancient genre of bios, or “biography.” The fourfold Gospel was explicitly recognized by the end of the second century.

The four Gospels tell the same basic story: Jesus ministers in several regions of Israel, teaching and performing miracles; he gathers followers and makes enemies (especially in the Jewish religious establishment); this opposition leads to his death by crucifixion at the hands of the Romans in Jerusalem; he is resurrected from the grave. All four accounts relate that Jesus’ followers recognized him to be God’s Messiah, the one through whom God’s plan of salvation was reaching its climax. For all their basic agreement, the four Gospels also differ, sometimes significantly, in their presentations of the life of Jesus. These differences are especially marked between the first three Gospels, on the one hand, and John, on the other. The many parallels between Matthew, Mark, and Luke—extending even to specific wording at many places—suggest that they are closely related. Accordingly, they are labeled the “Synoptic” Gospels (syn-optic is Greek for “seen together”). Mark’s Gospel may have been the first to be written, with both Matthew and Luke using Mark’s account to compose their own Gospels. John’s Gospel differs significantly from the first three, and it is not clear if it depends on any of the first three. The diversity in our Gospels can prove challenging at times, but a careful and charitable reading reveals that they do not contradict one another. Rather, they complement one another: God has used four different early Christian leaders to help his people understand the many facets of Jesus’ life and teaching.

Acts

The “Acts of the Apostles” serves as a bridge between the stories of Jesus’ life and the letters that instruct churches about Jesus’ significance. This book tells the story of the expansion of the early church, from the 120 disciples gathered together on the day of Pentecost in Jerusalem to significant numbers of believers scattered all over the Mediterranean world—including the great center of that world, Rome. The title “Acts of the Apostles” (abbreviated to “Acts” in the NIV) was given to the book not by its author but by later Christians who recognized the prominence of Peter (chs. 1–12) and Paul (chs. 13–28) in the book. Yet a better title might be “Acts of the Holy Spirit” because the author is especially keen to show how God’s Spirit, poured out on the church at Pentecost, is the power behind the apostolic preaching of the word of God. As the similarity between Acts 1:1 and Luke 1:1–4 reveals, the author of the third Gospel, Luke, the companion of Paul, wrote Acts also. Some key plotlines and theological themes bind these two volumes together.

Letters

The next major section of the NT comprises 21 letters. These may be divided into two basic parts: 13 letters written by the apostle Paul and 8 written by five other early Christian leaders. Most of them were written to churches but four of them were written to church leaders (1 and 2 Timothy, Titus, and 3 John; Philemon is addressed not only to a man named Philemon but to other Christians and the church in Colossae). The “letter” form was a popular means of communication in the ancient world that Christians adapted to maintain relationships among the widely scattered Christian communities (see The Letters of the New Testament). Written over the course of about 50 years to churches and individuals scattered all over the Mediterranean world, these letters deal with an incredible number of issues. Yet they are united in their concern to help believers understand how Jesus Christ must be the center and touchstone of all that believers think and do. Believers today read them with profit, not only to understand the many facets of Christian truth and to know how to live out the gospel in specific circumstances but also to appreciate how the gospel must be integrated into every aspect of the believer’s life.

Revelation

As the last book of the NT, Revelation appropriately focuses on the end of history. The climax of the book is the coming of Jesus Christ in glory to reward believers, punish unbelievers, and usher in the new heaven and the new earth (chs. 19–22). Yet Revelation is about much more than just the end of history. The book utilizes a popular Jewish genre called the “apocalypse” to take John (and us) into the unseen spiritual realm where the ultimate realities that dictate the course of our history are revealed. The visions that God gave to John provide believers with a vital perspective on all of history. These visions remind the church that, however difficult our circumstances might be, God is indeed on his throne (ch. 4); God has a definite plan for his people; God is infallibly carrying out this plan through Jesus, “the Lamb, who was slain” (5:12; see ch. 5); and believers must remain faithful to God in order to receive their ultimate reward from him.

How the New Testament Came Into Being

All of the NT books were written in koine, or “common,” Greek. This Greek was the lingua franca in most of the countries surrounding the Mediterranean Sea. It was the language that people with many different native languages would use to communicate with one another (much like English in our day). Jews who grew up in Palestine, for instance, would often learn Greek in addition to the Aramaic that was their native language at the time. Jesus and the apostles would have learned Greek so that they could interact with the many Gentiles who lived in their own country and surrounding regions. Greek was so widely used that when Paul, a Roman citizen, wrote a letter to the believers in the capital of the Roman Empire, he wrote not in the Latin of the empire but in Greek. This widespread, common language smoothed the way for the early evangelists, who could travel almost anywhere in the Roman Empire and effectively communicate the gospel in the Greek they already knew.

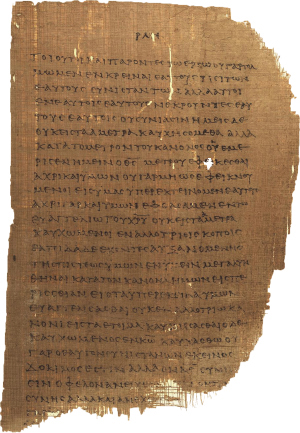

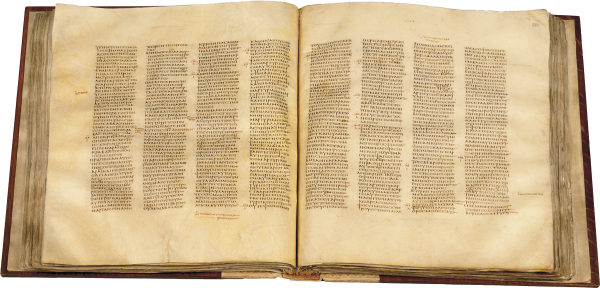

We do not know how soon the early Christians began to write about their faith. It is quite possible that Christians committed to writing some of the details about Jesus’ life and ministry shortly after the resurrection. But the earliest NT letter was written probably in the middle 40s, and the earliest NT Gospel was probably written in the late 50s or early 60s. These Christian authors would have used sharpened reeds or quills to transfer ink to papyrus, a paper made from the reeds of the papyrus plant. In the NT period, papyrus was rolled up to form scrolls; later in Christian history the codex, or book form as we know it, began to be used. We do not possess the original written text of any NT book. As the books of the NT were written and sent to their destinations, Christians undoubtedly came to realize how valuable these books would be if distributed more widely. Indeed, we see the beginnings of the wider distribution of the NT books in the NT itself; Paul encourages the Colossians to read the letter he sent to the Laodiceans and the Laodiceans, conversely, to read the letter he sent to the Colossians (Col 4:16). As this process continued, we can imagine early Christians wanting collections of several similar NT books, such as the letters of Paul or the Gospels. In order to preserve and to disseminate these books or collections of books, copies of the originals would have been made.

Today we possess over 5,000 manuscripts containing a part of (in most cases) or the whole NT. Some of these manuscripts contain only a few verses. Many of them contain several NT books, usually organized by type of book: Gospels, Acts, the letters of Paul, the “catholic” (i.e., general) letters, and Revelation. The earliest manuscript containing part of the NT dates from the early second century, but the most significant come from the fourth and fifth centuries. Scholars have devoted many centuries to studying these manuscripts in an effort to identity the “original text” of the NT. The fruit of this labor (called “textual criticism”) is a Greek text of the NT, called the modern critical text, that is without doubt very close to what the NT authors originally wrote. The sheer mass of evidence, the text’s origins from many parts of the ancient world, and its comparatively early date enable us to have great confidence that when we read this text, we are reading the words that God himself inspired their authors to record. Most modern translations of the Bible, such as the NIV, work from this reconstructed text, using text notes to signal places where the text may be somewhat uncertain.

The Canon of the New Testament

The NT itself refers to books written by early Christians that are not part of the NT (e.g., Paul’s letter to the Laodiceans [Col 4:16]). And there are many books written in the late first century and second century by apostolic fathers that were popular among early Christians but are not now found in our NT (e.g., The First Letter of Clement, The Shepherd of Hermas, The Letter of Barnabas). How did it come to be that the NT contains only the 27 books that we are familiar with?

This question involves what we call the canon. The Greek word kanon referred originally to a reed, and then to a rod, or bar, and eventually a rod used for measuring something. Hence kanon came to have the sense of a “standard.” The “canon” of the NT is the collection of those books that have been deemed to meet the standard for inclusion in Scripture. These books, and only these books, are the ones that the church has recognized as inspired by God and therefore providing authoritative divine guidance about Christian belief and practice.

The recognition that some early Christian books had the same status as the existing books of Scripture (the OT) can be traced back to the NT itself. In 1 Tim 5:18 Paul cites a saying of Jesus—“The worker deserves his wages” (Luke 10:7)—as “Scripture” along with a quotation from the OT. In 2 Pet 3:16 Peter criticizes people for twisting the meaning of some of the letters of Paul, “as they do the other Scriptures”—“the other” implying that Peter thinks of these Pauline letters as Scripture. But aside from these few references, the NT provides little guidance for deciding what books should belong to the canon of NT Scripture. Partly as a result of this silence, it took early Christians some time to settle on the limits of the NT canon.

Christians everywhere clearly recognized many NT books, such as the Gospels, Acts, and most of Paul’s letters, as Scripture at an early date. Other books took them longer to widely embrace as part of the NT canon, especially James, 2 Peter, 2-3 John, Jude, and Revelation. But these doubts are not surprising. Doubts about Revelation were due mainly to the animus against the apocalyptic style of the book shared by many early believers. The brevity of some letters meant that the church did not widely use them, which made them difficult to distinguish from the many forgeries circulating in the names of the apostles. Considering these historical circumstances and the diversity of the early church, what is remarkable is that virtually the entire early Christian movement came to agree on the identity of NT canonical books. The first list containing all (and only) the 27 canonical NT books is found in the Easter letter written by the famous early church theologian Athanasius in 367. The Third Council of Carthage (397) provided official church recognition of the 27 books of the NT canon.

Finally, it is especially important to emphasize that the early church did not create the canon; it recognized the canon. Early Christians used several criteria in their judgments. Apostolic authorship or connection with an apostle was important (Mark, for instance, was viewed as a disciple of Peter). More important, however, was conformity to the apostolic teaching, the “rule of faith” (Latin regula fidei). But most important of all was inspiration. God, in a sense, created the canon by inspiring what human authors wrote as they wrote certain books. He entered into this special work of inspiration, for instance, as Paul wrote Colossians, but not as he wrote to the Laodiceans. Early Christians recognized the unique significance and authority of certain books, and this recognition led to the decision to include them in the canon.

Reading the New Testament

God inspired the books of the NT so that people would have an authoritative record of his climactic revelation in his Son, the Lord Jesus. The NT has been translated into hundreds of languages so that people around the world can access this revelation in their own tongue. Whether you are a seasoned believer or someone who has picked up the Bible for the very first time, the message God has for you is (in the words Augustine heard long ago): “Take up, read!”

Some simple principles will help you as you read:

1. Ask God to help you understand. The NT itself warns that sin has affected the ability of humans to understand God’s truth (Rom 1:28; 1 Cor 2:14; Eph 4:18). Pray for illumination from the Spirit of God.

2. Look for connections with the OT. The NT is part of one large “book” (the Bible), and we should always seek to understand how a particular passage fits into this single story of God’s redemptive work. The NT authors themselves, soaked in this story, constantly point us to these connections. They make use of the basic categories of the OT (sacrifice, covenant, law, etc.), they quote the OT, they pick up language from the OT. NIV text notes, cross references, and study notes in this Bible will help readers identify many of these points of contact.

3. Recognize the different ways the NT communicates. The NT books use different genres—biography, history, letter, apocalypse—to communicate with us, and a good reader will take these into account. Some passages, such as Jesus’ teaching in the Gospels or the apostles’ teachings in the letters, address us quite directly, telling us what to believe or what to do (or not to do). Other passages, such as stories about Jesus in the Gospels or about the early church in Acts, give us insight into the nature of reality as God sees it, challenging us to adjust our worldview to align it with the worldview seen in these stories.

4. Remember that the NT books are occasional. While God designed the NT to speak to every generation of believers in every part of the world, a particular first-century person wrote each NT book to a particular first-century audience with first-century concerns in view. Fortunately, most of those first-century concerns involve basic spiritual realities that transcend time and place. But some of those first-century issues are different than ours, and we will understand and apply the NT message more effectively if we know something about that world. The notes on biblical passages in this study Bible are designed precisely to help the reader navigate these issues.

5. Compare Scripture with Scripture. Because NT books address specific issues in the first century, they will sometimes give advice that is directly relevant only for that time and place. Readers should follow the cross references provided in this Bible to see what the Bible says elsewhere about a particular topic. If, for instance, what the Bible says elsewhere contradicts a particular teaching, that teaching may have been limited to a special circumstance or period of time. If, on the other hand, parallel passages say much the same thing, we may conclude that the teaching applies generally.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()