WHO ARE THE MOST DANGEROUS MEMBERS OF THE VARIOUS secret societies skulking the earth, people with power to change our lives and direct the course of history? According to sources claiming inner knowledge of the group's true purpose, they are Freemasons. Masonic conspirators choose international leaders, launch wars, control currencies and infiltrate society, among other applications of their hidden powers, or so the tales propose. When anyone questions this premise, conspiracy theorists trot out an impressive array of proof, beginning with a recital of influential men through history who were undeniably associated with Masonry, including many signers of the U.S. Declaration of Independence. Who holds higher positions in the American pantheon of heroes and great thinkers than Benjamin Franklin, George Washington and Andrew Jackson? All were Freemasons. In fact, at least twenty-five U.S. presidents and vice-presidents have been active and enthusiastic supporters of Masonry. Two of them—Harry Truman and Gerald Ford—could boast 33rd Degree status, the highest level of recognition within the organization.

Masons dominated Western politics and cultures for years. Among their members were U.S. presidents George Washington and Harry S. Truman, British prime minister Winston Churchill, and the elegant Duke Ellington.

It is a remarkable achievement, this elevation of a private club with secret rituals into an incubator of leaders, visionaries and intellectuals. On the face of it, the Masons appear to inspire men of exceptional talent far beyond that of any other organization ranging from the Boy Scouts to Rhodes scholars. What is it about their values and systems that breeds such overachievers?

To a few fanatic historians—almost all of them Masons—at the root of their achievements is a historic and inspirational link with the Knights Templar, who began as Defenders of the Christian Faith, became the bankers of medieval Europe, and succumbed to the machinations of a greedy king and a complicitous pope.

Once acclaimed and admired for chivalrous deeds and good works on behalf of Christianity, the Knights Templar safeguarded pilgrims on their way to the Holy Land and battled Islamic armies for control of Jerusalem. Genuine knights in an era when that title brought respect and admiration, they obeyed rules of chivalry and asceticism, dedicating their lives to the glory of God and the protection of Christian pilgrims.

That was the admirable side of the society. The darker side hid rumors of associations between Templars and the Assassins, the replacement of Templar moral values with outright greed, a decline in commendable character traits and the pursuit of various obscene and blasphemous practices. These attributes are not a model for any high-profile organization seeking respect, let alone one that prides itself on providing world leaders and community benefits. But dark complexity and suspicion provided the necessary intrigue and color for a later group whose original objective was to protect the secrets of tradesmen. Along the way, the Templars’ spiritual leader managed to be compared to, and perhaps even mistaken for, Christ himself.

In their early years, Knights Templar were identified with chastity, piety and bravery. Later, their reputation grew less admirable.

The Templars were a product of the Crusades. And the Crusades, contrary to popular belief, were the result not of chivalrous intent or even a dedication to the Christian faith, but of feudalist obligation.

Historians, as is their manner, vacillate as much about the definition of feudalism as they do about its structure, and a few now reject the notion of a “feudalistic age.” Whatever title is hung upon it, Europeans living during the period between ad 800 and 1300 experienced a way of life that bridged inchoate barbarianism and the roots of democracy. During this time, kings may have claimed wide authority over lands we now know as France, Germany, Britain, but the countryside was effectively ruled not by monarchs but by individual lords and barons. Dominating the lands encompassed by their estates, the lords dispensed justice, levied taxes and tolls, minted their own currency, and demanded military service from citizens occupying their lands. Most lords, in fact, could field larger armies than could the king, who was often a figurehead ruler.

The social structure was many layered and clearly defined. Serfs represented the lowest level, performing basic labor and having no claim to any wealth they created. Vassals worked the land on behalf of the lord; knights, whose primary qualities included sufficient funds to own both a horse and armor, performed services on behalf of the lords; and the clergy administered spiritual assistance as required. Lords, in turn, were considered vassals to more powerful rulers, and all were formally considered vassals to the king.

Feudal loyalty flowed in two directions. The citizens made an oath of loyalty to the lord, paid taxes imposed by him, and attended the court when summoned. The lord's obligation included protecting the vassals from intruders, an act that was admittedly as much in the lord's interests as in the vassals’.

Out of this linear arrangement, subjected to the influence of Christianity, came the concept of chivalry. Vassals and knights, heeding the rights and property of their feudal lord, elevated the notion through terms such as “proud submission” and “dignified obedience” inspired, perhaps, by Biblical tales of Christ's actions. Phrased in this manner, behavior that appears to mirror a master–slave relationship was spun into something more reputable and uplifting. As contradictory as it may sound, individuals could elevate their status by lowering their position on behalf of some splendid goal. Popular literature suggests that the incentive for chivalrous behavior was romantic interest in an elegant lady who had stolen the knight's heart, and to whom he pledged eternal reverence. In reality, a knight's “proud submission” was made either to God or to the lord who controlled the knight's destiny. The romantic aspect of chivalrous behavior, glorifying womanhood in a manner that combined worship of the Virgin with suppressed sexual desire, remains an inspirational source for much fiction but was basically a by-product of a deeper motivation.

Chivalric demands were rigid. Obligations were expected to be fulfilled, and vassals and knights accepted a sacred duty to defend by arms the honor and property of the class above themselves. Since the pyramid structure of medieval society set Christ at the apex, lords, knights and vassals alike were equally obligated to defend His rights and honor.

With feudalism solidly established throughout Europe, lords and knights, accompanied by a retinue of servants, began the practice of making pilgrimages to Jerusalem as a means of expressing their Christian faith. Reviving a concept dating back to early Greeks, who trekked to Delphi in search of wisdom, European Christians began setting off on pilgrimages to the Holy Land, first in honor of Christ, later as a means of cleansing their sins, and later still in response to direct instructions from the pope.

Prominent early pilgrims in search of spotless souls included Frotmond of Brittany, who murdered his uncle and younger brother; and Fulk de Nerra, Count of Anjou, who burned his wife alive, which was evidence of serious marital discord and abuse even in those tumultuous pre-feminist times. Both men sought forgiveness with a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and both achieved success, albeit in contrasting measure.

After years spent wandering the shores of the Red Sea and searching the mountains of Armenia for relics of Noah's Ark, Frotmond returned home swaddled in the warmth of forgiveness for murdering his relatives, and passed the remainder of his days in the convent of Redon. For his sins, Fulk de Nerra wandered the streets of Jerusalem accompanied by a retinue of servants who beat him with rods while he repeated the words, “Lord, have mercy on a faithless and perjured Christian, on a sinner wandering far from his home.” His apparent sincerity impressed the Muslims so much that they granted him entry into the room of the Sacred Tomb, normally forbidden to Christians, where he threw himself prostrate upon the bejeweled floor. While wailing for his wretched soul, de Nerra managed to detach and pocket a few precious stones from the site.

The examples set by Frotmond, de Nerra and others had their impact on devout Christians. Around ad 1050, making a pilgrimage to the Holy Land was considered a duty for every able Christian as a means of assuaging guilt and appeasing the wrath of God, and the Church began assigning a pilgrimage as a common means of penance. By 1075, pilgrimage trails had become as well defined and well traveled as trade routes.

The pilgrims’ trek, usually tracing the Adriatic coast before turning overland to Constantinople and across Asia Minor to Antioch, was neither more nor less dangerous than any other journey of similar length. Their established route, however, proved a factor in 1095 when Byzantine emperor Alexius Comnenus pleaded for Pope Urban ii to help in defeating a group of Muslim tribes known as the Seljuk Turks. After seizing Anatolia, the Byzantine Empire's richest province, the Seljuks occupied Antioch, Tripoli and finally Jerusalem. Now, it seemed, they had their eye on Constantinople itself. If the pope could organize an army of dedicated Christians to assist Byzantine troops, Alexius suggested, together they could retake Antioch and restore Jerusalem itself to Christian rule.

The promise of Christian rule over the Holy Land, bolstered by expectations of wealth tapped from the Byzantine emperor's own treasury, was enough to inspire Urban ii to launch the first papacy-sanctioned holy war. Thus, almost two hundred years of horrific slaughter on both sides began with a goal as much mercenary as it was spiritual, and in 1096 the first of nine crusades set off, inspired by Urban's cry Deus vult! (God wills it!)

Deciding to take part in a crusade was a serious decision, even for the most devout of Christians. It meant at least two years of travel across rugged and often hostile country, although later crusades reduced the time by sailing eastward along the Mediterranean from Provence. Seeking food and shelter during the long journey from Europe to Palestine and back, pilgrims and crusaders had to deal with open hostility from both the Muslims and Greek Orthodox administrators. In response Gerard de Martignes established a hospital in Jerusalem to serve as a refuge. Consisting of twelve attached mansions, the facility included gardens and an impressive library. Soon local merchants created an adjoining marketplace to trade with the pilgrims, paying the hospital administrator two pieces of gold for the right to set up stalls.

This was too good for feudal entrepreneurs to ignore. When the flow of pilgrims swelled to an endless flood, a group of Italian traders from the Amalfi region established a second hospital near the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, this one operated by Benedictine monks, with its own profitable marketplace. Soon the second facility began overflowing, promoting the monks to create yet another hospital, dedicating it to St. John the Compassionate.

The men of St. John the Compassionate elevated the concept to a new spiritual status. They devoted their lives to providing safety and comfort for pilgrims by treating their patients as their masters, creating a prototype for every charitable organization that followed them, although none matched their dedication and humility. This practice, of course, reflected the true origins and goals of chivalry, attracting many knights who set aside their military objectives in favor of emulating the most charitable of Christ's teachings. Their military bearing and discipline were never wholly discarded, however. Among those they served, the knights were liberal and compassionate; among themselves, they were rigid and austere. They pledged vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, and their dress became a black mantle bearing a simple white cross on the breast. They were called the Sovereign Military Order of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta, known simply as the Hospitaliers.

The two Templars on horseback, as shown on their seal, indicated brotherhood, but later generations spied a sexual reference.

Vows of poverty, chastity and obedience may have suited their obligations to chivalrous behavior (and, they no doubt anticipated, facilitated their entry into heaven), but they did little to protect the Hospitaliers from the dangers of attack by various factions in the Holy Land. With time, the Hospitaliers grew focused almost as much on their military actions in defense of their order as on their acts of benevolence. Most were armed knights, after all, noble of birth and adhering to the high standards of true chivalry.

They were also as human as anyone else, of that era or ours, and when powerful European duchies expressed admiration for the Hospitaliers by awarding them extensive lands in Europe, the members accepted the donations gladly. In addition to this source of income, they assumed the right to claim booty seized from defeated Muslim fighters, and by the time Gerard died in 1118 the Hospitaliers had acquired substantial assets from their patrons, and exceptional independence from Church authority. What began as selfless dedication to the poor, injured and diseased had evolved into an organization more akin to a modern-day service club, whose well-heeled members were at least as interested in fraternal association and public status as they were in helping their neighbors.

The Hospitaliers may have been capable military men, but their raison d’être continued to be public service. Battling Muslims while fulfilling their obligations was proving a distraction from their primary goal, and others were needed to direct as much energy into fighting the enemy as the Hospitaliers were investing in caring for Christians.

It may be cynical to imply that the wealth accrued by the Hospitaliers as a result of their charitable services inspired their more celebrated brethren, but history suggests it played a role. In any case, a new society was formed within ten years of Gerard's death. Comprised originally of nine knights led by Hugh de Payens, the followers claimed the same ascetic and pious characteristics that distinguished the original Hospitaliers. This new group, however, focused on the hazards faced by pilgrims and Crusaders—by now the distinction was growing blurred and almost meaningless—during their trek to the Holy Land and their stay in Jerusalem.

The hazards arose from multiple threats. Egyptians and Turks resented passage and intrusion through their countries, Islamic residents of Jerusalem objected to the pilgrims’ presence, nomadic Arab tribes attacked and robbed the travelers, and Syrian Christians expressed hostility towards the foreigners.

Much of the group's early reputation for humility and valor was rooted in de Payens’ personality, described as “sweet-tempered, totally dedicated, and ruthless on behalf of the faith.” To a modern sensibility, the concept of being sweet-tempered and ruthless may appear contradictory, but to medieval observers they were perfectly compatible. A battle-hardened veteran of the First Crusade, de Payens took delight in recounting the number of Muslims he had slain without, apparently, souring his day-to-day charitable mood. And why should he? The even more pious Bernard of Clairvaux had declared that the killing of Muslims was not homicide but malicide, the killing of evil. Thousands of dead Muslims in the Holy Land may have begged to differ, but their opinions were rarely sought.

So de Payens, single-minded to the exclusion of everything except the worship of God and the slaughter of Muslims, gathered men around him who committed themselves to protecting pilgrims from danger in the same manner that Gerard's Hospitaliers were healing and feeding them. The new group, de Payens announced, would combine the qualities of ascetic monks and valiant warriors, living a life of chastity and piety, and employing their swords in the service of Christianity. To aid them in achieving this somewhat contradictory role, they chose as their patroness La Dolce Mère de Dieu (The Sweet Mother of God), and vowed to live according to the canons of St. Augustine.

Baldwin ii, then ruling as King of Jerusalem, was sufficiently impressed with the group's character and goals to award them a corner of his palace for their living quarters, and an annual stipend to support their work. Access to their quarters was through a passageway adjoining the church and convent of the Temple, and so they anointed themselves as Soldiery of the Temple, or Templars.

With time, the Templars impressed various noblemen who proffered the same kinds of financing arrangements as the Hospitaliers enjoyed. When one French count announced that he would contribute thirty pounds of silver annually to support the Templars’ activities, others followed suit, and soon the nas-cent movement was awash in the kinds of riches it originally planned to reject.

To their credit, for the first several years of their existence the Templars resisted temptations to use their growing wealth for anything except the support and defense of pilgrims. Seven years after the group's formation, Bernard of Clairvaux wrote of the Templars,

They go and come at a sign from their Master. They live cheerfully and temperately together, without wives and children and, that nothing may be wanting for evangelical perfection, without property, in one house, endeavoring to preserve the unity of the spirit in the bond of peace, so that one heart and one soul would appear to dwell in them all. They never sit idle or go gaping after news. When they are resting from warfare against the infidels, not to eat the bread of idleness they employ themselves in repairing their clothes and arms, or do something which the command of the Master or the common good enjoins.

No unseemly word or light mocking, no murmur or immoderate laughter, is let to pass unreproved…. They avoid games of chess and tables; they are adverse to the chase and equally so to hawking, in which others so much delight.

They hate all jugglers and mountebanks, all wanton songs and plays, as vanities and follies of this world. They cut their hair in obedience to words of the apostle…. They are seldom ever washed; they are mostly to be seen with disordered hair and covered with dust, brown from their corselets and the heat of the sun….

Thus they are in union strange, at the same time gentler than lambs and grimmer than lions, so that one may doubt whether to call them monks or knights. But both names suit them, for theirs is the mildness of the monk and the valor of the knight.

This was not exactly a life of beer and skittles. Even the Cistercian monks, who represented a model for the Templars, sought pleasure from life while managing to avoid the risk of death on the battlefield. Under these circumstances, only men of the highest character and most sincere virtue could endure a career as a Templar, but among ambitious and pious young men the call of chivalry was difficult to ignore. Impressive numbers of them sought membership in the Templars, swelling the ranks and raising the group's profile among European nobility, who expressed their support by pledging money and land, and sometimes their own sons.

As membership in the Templars grew, a formal structure was imposed on the organization. Three classes were established: knights, who were men of noble families, neither married nor betrothed, and who bore no personal debt; chaplains, who were required to take vows of poverty, chastity and obedience; and serving brethren, men of wealth and talent who lacked the noble birth requirement of the knights. Eventually the brethren were divided into brethren-in-arms, who fought alongside the knights; and handicraft brethren, who performed menial chores of baking, smithing and caring for the animals, but were held in the lowest esteem within the order.

Both knights and chaplains were required to undergo a rigid initiation process and this practice, extending in modified form down to the present day, forms the root of the perception of Templars and their descendants as a secret society.

On the evening of a nominee's reception into the order, he was inducted in the presence of other knights within a chapel. No one else could be in attendance, nor could the candidate divulge when, where or even if the ceremony was taking place.

The procedure focused on warning the aspirant of the difficulties he was about to encounter, and demanding that he swear allegiance to the Templars’ purpose before God. Reading an account of the ceremony today suggests the initiation was a form of Middle Ages boot camp. When he wished to sleep, the candidate was told, he would be ordered to watch. When he wished to watch, he would be ordered to bed. When he wished to eat, he would be ordered to work. Could he agree to these conditions? Each demand was to be answered, clearly and loudly, with the response, “Yea, sir, with the help of God!” The initiate was to promise never to strike or wound a Christian; never to receive any service or attendance from a woman without the approval of his superiors; never to kiss a woman, even if she were his mother or sister; never to hold a child at the baptismal font or be a godfather; and never to abuse any innocent man or call him foul names, but always be courteous and polite.

Who could resist an order dedicated to such chivalrous behavior and high Christian principles? Not the Church. In 1146 Pope Eugenius iii declared that Templar knights could wear a red cross on their white tunic (chosen in direct contrast with the Hospitaliers) in recognition of the martyrdom they faced, and that they were henceforth free of direct papal supervision, including the risk of excommunication. This generated an even greater flow of lands, castles and other assets into their treasury from impressed patrons.

There is no infinite resistance to perpetual temptation, and the seeds of the organization's downfall were soon sown. Rumors spread that the Templars were engaged in extortion from the Assassins. The claim arose from the murder of Raymond, Comte de Tripoli, assumed to have been carried out by the Assassins. In response, the Templars entered territory controlled by the Assassins, but instead of challenging the Assassins in battle they demanded a tribute of 12,000 gold pieces. While there is no record that the Assassins made any such payment, some time later they dispatched an envoy to Amaury, then King of Jerusalem, offering to convert to Christianity if the Templars would forego the tribute. Clearly, some sort of accommodation had been reached.

Later, Templars intercepted Sultan Abbas of Egypt as he fled into the desert with his son, his harem and a goodly portion of stolen Egyptian treasures. After killing the Sultan and seizing the treasure, the Templars negotiated a deal with the Sultan's enemies to return the son to Cairo in exchange for 60,000 gold pieces. This may have been business as usual for the times, except that the son had already agreed to convert to Christianity, which should have been enough justification to spare his life. Instead, when the Templars’ deal with the Egyptians closed, the son was placed in an iron cage and sent back to Egypt where, as he and the Templars knew, he faced death by protracted torture.

Incidents such as these marked the decline of the Templars from an ascetic order dedicated to the protection of the poor and helpless into an organization as focused on material gain as is any modern-day corporation. In fact, they set up an extensive banking system expressly to transfer money and treasures between Palestine and Europe, an action totally unrelated to their purported oaths of charity and poverty.

Their corruption did not end with money, and their change from strict asceticism to expansive materialism parallels any contemporary rags-to-riches tale. In place of modesty and humility, they grew haughty and rapacious, and they employed any deception at hand to build their impressive treasures to greater heights. In 1204, word spread throughout Palestine that an image of the Virgin near Damascus was issuing a juice or liquor from its breasts, and consuming the liquid was proving miraculous at removing sins from the souls of pious victims. The location, unfortunately, was a fair distance from Jerusalem, along a road often raided by bandits. The Templars proposed a solution. They would risk making the journey to the image, milk it of the miraculous liquor, and bring it to the pilgrims—for a price, of course. Both the demand and the price, as might be expected, shot skyward, and the magic elixir generated substantial income for an organization launched on the basis of maintaining total poverty.

Not all of the Templar treasures could be spent on the poor or on battling Muslims. A good deal of it appears to have been invested in wine and other delights of the flesh. Soon “drink like a Templar” became a common phrase to describe someone with an excessive taste for the grape, and the Germanic language acquired a new description for a house of ill-fame: Tempelhaus.

With a life of ease and fulfillment, who wanted to wear hair shirts among Muslims in Palestine? Not the Templars, who appeared more interested in acquiring wealth than in defending the Christian faith. Their original brothers-in-arms, the Hospitaliers, had also shifted their values towards mercenary rather than spiritual incentives. They had also abandoned their emphasis on sacrifice and charity, becoming as effective on the battlefield as the Templars themselves. For several years both groups of knights sniped at each other until, in 1259, they engaged in a battle launched by the Templars reportedly in pursuit of their rival's treasure. More zealous (and perhaps more numerous), the Hospitaliers won, cutting to pieces every Templar who fell into their hands. Soon after, the Templars retreated to Europe where, after all, the money was.

By 1306, the Templars were nicely settled on Cyprus, close enough to Palestine to maintain the premise that they were still involved in their original mission, and far enough away from raiding Muslims to enjoy safely the benefits of their wealth. In that year Pope Clement V, who had assumed the papal throne only months before, decided to address rumors about the Templars engaging in “unspeakable apostasy against God, detestable idolatry, execrable vice, and many heresies.” He summoned the Grand Master of the Templars, a charismatic man named Jacques de Molay, to Rome for an explanation.

De Molay, one of history's most colorful figures, stood over six feet tall with an appearance and bearing that might have qualified him as a medieval show-biz celebrity. Born about 1240 in Burgundy of a minor noble family, de Molay joined the Templars at age twenty-five and served valiantly in Jerusalem before being elected Grand Master at age fifty-five.

Arriving in Rome with sixty Knights Templar, de Molay also brought 150,000 gold florins, and substantial quantities of silver, all acquired by the Templars during their various forays in the Middle East. He left several days later with the papal equivalent of an apology, Clement explaining, “Because it did not seem likely or credible that men of such religion who… showed so much great and many signs of devotion both in divine offices as well as in fasts… should be so forgetful of their salvation as to do these things, we are unwilling to give ear to this kind of insinuation.” De Molay may have departed Rome with Clement's approval ringing in his ears, but he left behind the gold florins and silver.

Sensing a bribe, Philippe le Bel, the French king, grew outraged. Once a supporter of the Templars, he now turned against them, partially in reaction to their flagrant lifestyle, and partially because of their growing power and wealth; he feared the former and lusted after the latter. The Templars, Philippe determined, were to be dissolved and their treasury, the bulk of it stored within Philippe's domain, would be placed in the hands of the Crown. To achieve this, Philippe employed a device familiar to fans of contemporary crime stories: a jail-house snitch.

A former Templar named Squin de Flexian, imprisoned on charges of insurrection and facing a certain death sentence, learned of Philippe's dislike of the organization. Calling his jailer, de Flexian announced that he had dire, dark secrets of the Templars to pass on to the king. This was enough to earn de Flexian a junket to Paris, where he rambled through a litany of charges against the Templars, including secret alliances with the Muslims, initiation rites that included spitting on the cross, impregnating women and murdering their newborn babies, and ceremonies involving various acts of debauchery and blasphemy. As expected, de Flexian's tales entranced the monarch and his court, who could not hear enough of the fascinating details. Debauchery? Blasphemy? Alliances with the enemy? Secret ceremonies? What monarch could refuse to take action against these fiends, especially with several thousand gold florins, untold treasures of silver, and extensive lands and castles waiting to be seized?

2 This fell on a Friday, giving rise to the superstition of unfortunate events occurring on Friday the thirteenth.

On October 13, 1307,2 in an action worthy of a gifted military field commander, Templars were arrested in coordinated raids all across Europe, with the most brutal apprehensions occurring in France. Under torture many Templars, including de Molay, confessed to activities similar to those described by de Flexian (who was hanged for his troubles). For several years the imprisoned Templars tried to defend themselves against vile charges brought against them by the French king until, in 1313, the pope announced that the Templars were to be abolished. Depending on their rank, their admissions of guilt and their sincerity in rebuking their sins, members were either banished or set free, with the exception of de Molay and three of his closest confederates.

Brought before a papal tribunal on a stage in front of Notre Dame cathedral, the four Templars were about to be sentenced to spend the rest of their lives in prison when de Molay rose to speak. In direct and inspirational language, the Templar Grand Master protested his innocence and decried the confessions made under torture, many incriminating other Templars. His adamant refusal to admit wrongdoing and his demand for an opportunity to plead his innocence to the pope was supported by the brother of the Dauphin of Auvergne, one of the three other high-ranking Templars charged with similar crimes.

The tribunal was dumbfounded. They expected the Templars to receive their fate in silence and be grateful that their lives had been spared. The French king, upon hearing the news, was not dumbfounded at all. He was outraged, and demanded that the two Templars not only be burned at the stake, but that it be done slowly so that the men suffered as much agony as possible.

The following day, de Molay and Guy of Auvergne were trundled to the downstream point of the Île de la Cité, a site now known as the Square du Vert-Galant, one of the most attractive locations in all of Paris. Still declaring their innocence they were stripped naked and bound to posts. Then, in the words of one Templar scholar,

The flames were first applied to their feet, then to their more vital parts. The fetid smell of their burning flesh infected the surrounding air, and added to their torments; yet still they persevered in their declarations [of innocence]. At length, death terminated their misery. Spectators shed tears at the view of their constancy, and during the night their ashes were gathered up to be preserved as relics.

Jacques de Molay died a martyr's death and helped elevate the organization's tarnished reputation.

The Templars’ treasury was seized by Philippe, who claimed the majority of the prize to cover expenses incurred in trying and executing its members. The leftover amount he distributed to the Hospitaliers and King Edward ii of England, who had somewhat reluctantly agreed to banish Templars from his own realm.

Legend has it that de Molay, while being tied to the stake for his execution, predicted that Pope Clement would follow him within forty days and the king would join them all within a year. If so, he was correct. Clement died of colic the following month and, while his body was lying in state, a fire swept through the church and consumed most of his corpse. A few months later, Philippe was thrown from his horse and broke his neck.

In another, more contemporary incident, de Molay has been identified as the figure imprinted on the mysterious Shroud of Turin. First displayed in 1357, the shroud was claimed to have been recovered from Constantinople by crusaders who sacked the city in 1307. The apparent imprint of a bearded figure on the material was attributed to Christ, suggesting the shroud had been used to wrap his body after it had been removed from the cross. Carbon dating, however, revealed that the shroud material dated only as far back as the late thirteenth century, initiating new speculation that de Molay had been wrapped in the material following one of his torture sessions during his years of imprisonment. The size and appearance of the image on the shroud could as easily be de Molay's as anyone's, adding to the mystique of de Molay's martyrdom.

The actions of Philippe, Edward and other rulers who were persuaded to follow the French lead failed to annihilate the Templars, and remnants of the society retained the organization's structure in a deeply clandestine manner lest they share the same fate as de Molay and Guy of Auvergne. Secret activities that had been conducted under de Molay's leadership were enhanced and sanctified. A few sources claim that documents prepared by de Molay shortly before his death appointed Bertrand du Guesclin to succeed him as Templars Grand Master, and the leadership position was filled over time by a succession of prominent French citizens, including several princes of the house of Bourbon.

More enduring, especially among French citizens, has been a suspicion that Philippe failed to seize all the Templars’ treasures. Stories have abounded for centuries that immense troves of gold and jewels lay waiting for someone to locate them. One tale concerns pretty Rosslyn Chapel near Edinburgh, whose intricate stone carvings are claimed by some to be a secret code understood only by Templars and Freemasons. When deciphered, the code supposedly identifies the location of the Holy Grail and the Templars’ fortune, both hidden nearby. The chapel's link to the Templars is questionable, because it was built 170 years after the death of de Molay, yet the story persists in spite of the fact that extensive investigation and excavation have revealed nothing remotely of value or interest around or beneath the chapel. Another legend suggests that much of the Templars’ wealth was buried on Oak Island, in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Nova Scotia.

Tales of Templar treasure may be rampant, but real-life Templars today are not—except, perhaps, via a lineage extending down to modern-day Freemasons. Masons have been of two minds about the linkage with Templars. On one hand, the idea of Masons as direct descendants of the martyred Templars adds an aura of mystique and grandeur to the organization; whatever their faults, the Templars’ image has benefited from the burnishing of time, and they are now widely viewed as noble knights sacrificed to a larcenous king and a perfidious pope. On the other hand, no direct historical association can be found between the Templars and Masons—which, of course, has not prevented widespread speculation and garish fable from connecting the two. Should an organization like the Masons, striving to be recognized and admired for maintaining a high level of scrupulous behavior, foster a relationship that has no basis in fact? The latter point is no longer a serious concern, because given their declining membership and recent debacles, the Masons could benefit from bathing in reflected glory from the Templars.

The Masonic movement has fallen far and hard, especially in the United States where its greatest glory and most enduring strength once lay. Any review of U.S. history encounters Freemasons lurking behind every treaty, battle and statute, and their members holding the offices of Secretary of State, General of the Army and Supreme Court Justice. From George C. Marshall, through Generals John J. Pershing and Douglas MacArthur, to Supreme Court Justices Earl Warren and Thurgood Marshall, Freemasons dominate seats of American power in greater numbers than does any other organization. No fewer than sixteen U.S. presidents have proudly declared their Masonic status.

Nor is this an exclusively American phenomenon. Sir Winston Churchill, Canadian prime minister John Diefenbaker, and at least four presidents of Mexico all held high positions within Freemasonry. Can any other closed society claim such extensive influence on seats of power over so many years?

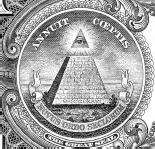

Proof that Masons exert enormous power over world events, should you choose to believe conspiracy buffs, can be found in pockets, purses and billfolds around the world. Every U.S. dollar bill bears the Great Seal of the U.S. on its reverse, a symbol many believe confirms Freemasonry's dominance and control of the country. The seal's design includes an eye within a triangle floating above an apparently unfinished pyramid. On the base of the pyramid are engraved the Roman numerals for 1776 (mdcclxxvi), and the design is framed by two Latin phrases: Annuit Coeptis (Providence Has Favored Our Undertakings) and Novus Ordo Seclorium (A New Order of the Ages). According to those who fear the Masons, the eye and pyramid are Masonic symbols, and the manner in which the emblem is flaunted proves their power remains unchallenged.

The Great Seal on the U.S. dollar—is it proof of a Masonic plot?

Or does it? Masons have long used a triangle as a symbol of their membership but only because it represented a set-square, a tool used by the stonemasons who created the organization. In any case, the Great Seal of the U.S. depicts not a triangle but a pyramid, chosen because it represents strength and stability, important qualities for a nascent country. The eye represents the all-seeing vision of God, nothing more, and while it is indeed framed within a triangle, triangular shapes have been popular among Christian societies for centuries, representing the Trinity of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

Historical evidence supports this view. Writing on behalf of the Freemasons in 1821, Thomas Smith Webb noted that the Masons did not adopt either the eye or the triangle as a symbol until 1797, fourteen years after the U.S. Congress approved the Great Seal. Webb explains the components of the seal in fine early-Victorian prose:

Although our thoughts, words and actions may be hidden from the eyes of man, yet that All-Seeing Eye, whom the Sun, Moon and Stars obey, and under whose watchful care even comets perform their stupendous revolutions, pervade the inmost recesses of the human heart, and will reward us according to our merits.

Some skeptics believed him. Most did not.

Freemasons have been trying to shake off this connection with the Great Seal of the U.S. for two centuries without success. They have also attempted to disprove the theory that Freemasons are determined to carry out acts of revenge on the Templars’ behalf for abuses committed against the group almost 800 years ago. In the process, they also deny an association with the Illuminati, an organization of free-thinking intellectuals whose goal, two centuries before cnn, was nothing less than global control of social and political thought; or that they installed popular personalities in positions of power to carry out secret Masonic strategies.

Crusading knights, revenge-driven descendants, subversive currency, global tyrants, celebrity insurgents—what is really behind the Masonic movement? As with all secret societies, the reality suggests both more and less than the eye reveals.

While a few fringe commentators declare that Adam was the first Mason (the same crowd who claim that remnants of de Molay's group escaped to America 200 years ahead of Columbus), the origin of the Freemasons is as simple and direct as their name. In seventeenth-century England, craft organizations began forming as a means of concealing specialized knowledge of their trade from outsiders who might profit from it. The craft guilds declared that they were setting quality standards among the craftsmen; they were less open about their goal of ensuring higher incomes for members by restricting the number of people qualified to join and elevating wages accordingly.

Among the most powerful craftsmen of their time were stonemasons, who possessed the tools and skills to build strong, straight walls. The proof of their talents is evident throughout Britain, where many stone structures remain as solid as the day they were constructed 400 years ago. Mason skills were rated according to three levels: Entered Apprentice, Fellowcraft and Master Mason. Each level of skill elevated the mason to a higher rank of recognition, or degree, entitling him to earn appropriately higher wages. Secrecy became paramount among the masons, who chose their companions carefully and swore new initiates to silence about the techniques they had perfected over centuries. To provide control over their members and ensure that the secrets remained hidden, masons were organized in small community-based lodges with each lodge electing a leader or master.

What began as an organization of craftsmen evolved into something quite different in June 1717, when the leaders of four London lodges gathered at the Apple Tree Tavern to form the Grand Lodge of Freemasons. The goals of the Grand Lodge extended beyond those of the original craft guild to encompass the status of a pseudo-religion, reflecting established Protestant values. Members vowed to work within Christian principles, rationalize the teachings of Christ, and empty Christianity of its mystery through the application of logic and scientific analysis. This marked the beginning of Freemasonry as a global power.

The Freemason concept spread to France and the rest of Europe, and in the process it also spread its recruitment net to snare a wider range of members. No longer restricted to trades-men, Freemasonry began to welcome all men of qualified social stature, providing them with a fraternal organization where they could exchange ideas, pursue common interests, and make important business and professional contacts. Retaining the oath of secrecy among its members, the movement added a mystical initiation ceremony. Soon after, the historical intrigue tying Masons to the Templars began to spread.

A historical link with romantic martyrs garnered as much status for organizations and individuals 300 years ago as it does today. Adding color to the fraternal basis of their organization, Freemasons began to claim descendancy from the Knights Templar. The hypothetical combination transformed an organization originally based on the practical concerns of tradesmen into a fraternal assembly of upper-class businessmen and professionals.

Once their association with the Templars took hold, many enthusiastic Masons began to build an aura of mystique around their group. Like all mystiques, this one acquired a patina of authenticity with time. Scottish Freemasons claimed that several of de Molay's most dedicated followers had escaped France and fled to Scotland following their leader's execution. A few went further, maintaining that de Molay himself had escaped execution and arrived in Scotland, where he fought with Robert Bruce at the Battle of Dupplin in 1332 and the Battle of Durham in 1346.3

Masonic records trace the Templar–Mason connection back to an oration delivered in 1737 in the Grand Lodge of France by a Mason named Chevalier Ramsay. Ramsay claimed Freemasonry dated from “the close association of the order with the Knights of St. John in Jerusalem” during the Crusades, and that the “old lodges of Scotland” preserved the genuine Masonry abandoned by the English. From this rather dubious historical connection spun the Scottish Rite or, as the Masonic constitution identifies it, the Antiquus Scoticus Ritus Acceptus, the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite. A more likely explanation stems from the mid-eighteenth–century emigration by Scottish and Irish Masons to the Bordeaux region of France, where they were identified as the Ecossais.

The Ecossais extended the original three degrees of Masonry first to seven degrees and later to twenty-five degrees, eventually evolving into thirty-three degrees today. Masons who choose to advance beyond the basic three degrees join the Scottish Rite.

3 In recognition of de Molay's leadership and martyrdom, the International Order of de Molay was founded as a fraternal organization for young men aged 13 to 21. Operating under the direction of Masonic advisers, it is essentially a recruiting service for the parent organization.

American colonists established a Masonic lodge in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1733. Memberships in this first American lodge grew spectacularly, and by the American Revolution over 100 lodges were listed. In fact, members of the St. Andrew Masonic Lodge effectively kick-started the revolution with the Boston Tea Party, when they dressed as Mohawk Indians and dumped British tea into the harbor to protest unfair taxation. As in England, American Freemasons represented the most ambitious, gifted and powerful men in society, so it is no surprise that fifty-one of the signers to the Declaration of Independence supposedly identified themselves as Masons. With so many prominent rebels actively involved, it's reasonable to claim that Freemasons, more than any other single group, instigated the revolution. The list included luminaries such as George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Patrick Henry, John Hancock, Paul Revere, John Paul Jones, Ethan Allen, Alexander Hamilton and, to the later chagrin of his fellow American Freemasons, Benedict Arnold. With independence achieved, American Freemasons cut all ties with Britain and launched an exclusively American Grand Lodge in 1777.

Freemasons in the U.S. strengthened their organization, refined their procedures, and extended their influence beyond the lodge halls more than members in any other country. Along with an emphasis on rituals and secrecy, their growth and authority produced speculation about their true motives, encouraged at the outset by Masonic practices and policies; the more mystery attached to the order, the more they would be regarded as powerful men engaged in shadowy activities. Decisions were made not to dilute this vision, but to enhance it in every way possible. The location for the Supreme Council of Scottish Rite Freemasonry, for example, was chosen as Charleston, South Carolina, because that city is located on the 33rd parallel, reflecting the thirty-three degrees of Masonic membership.

To outsiders, this kind of conscious effort to create inscrutability proved either amusing or menacing, and over the years a number of outlandish claims were made about the true goals of Freemasons. Some rather astonishing practices and achievements were credited to them, including the following:

FREEMASONS ARE IN LEAGUE WITH THE ILLUMINATI. Like Russian dolls, secret societies are reputed to exist within each other, large groups concealing smaller, more concentrated divisions through ancient alliances. Among the most persistent claims by conspiracy buffs and anti-Masons generally is the allegation that Freemason lodges secretly harbor members of the Illuminati.

In the view of these alarmists, the Illuminati are the people who pull the strings on puppeteers who believe they themselves are pulling strings attached to other puppets. Shadows within shadows, Illuminati members supposedly hover in the background among Masons and other groups, including the Priory of Sion, followers of Kabbalah, Rosicrucians and, in a test of theological extremes, the Elders of Zion.

Launched in 1776 by Adam Weishaupt, a Bavarian Jesuit scholar described as “an unpractical bookworm without necessary experience in the world,” the Illuminati (“Enlightenment”) was created as a secret society the true objectives of which would be revealed to its members only after they achieved a “priestly” degree of awareness and understanding. Those who managed to survive Weishaupt's process of selection and preparation eventually learned they were cogs in a political/philosophical machine regulated by reason, an extreme extension of the founder's “reason over passion” Jesuit education. Thanks to the Illuminati, people would be liberated from their prejudices and become both mature and moral, outgrowing the religious and political restrictions of church and state.

Achieving this utopia would be a gain not without pain, however. Illuminati members were to observe everyone with whom they came into social contact, gathering information on each individual and submitting sealed reports to their superiors. By this means, the Illuminati would control public opinion, restrict the power of princes, presidents and prime ministers, silence or eliminate subversives and reactionaries, and strike fear in the hearts of its enemies. “In the bosom of the deepest darkness,” wrote one of the movement's early critics, “a society has been formed, a society of new beings, who know one another though they have never seen one another, who understand one another without explanations, who serve one another without friendship. From the Jesuit rule, this society adopts blind obedience; from the Masons it takes the trials and the ceremonies; and from the Templars it obtains subterranean mysteries and great audacity.” Without a doubt, this was a force to be reckoned with.

One of Weishaupt's early strategies was to ally himself with the Freemasons, a move that initially proved successful. Within a few years “Illuminated Freemasons” were active in several European countries. But as details of their true aims escaped, public attitude turned against them until, in August 1787, Bavaria declared that recruiting Illuminati members was a capital crime. This managed to drive the society more deeply underground, but it also persuaded Weishaupt that his vision was seriously flawed. After renouncing his own order and writing several apologies to mankind, Weishaupt reconciled with his Catholic religion and spent his last few years helping to build a new cathedral in Gotha.

During the Illuminati's limited tenure, tales circulated that it was responsible for the outbreak and progress of the French Revolution, a claim that is almost laughable in view of the group's emphasis on reason instead of passion. Few events in history were propelled by raw passion more than the overthrow of the French throne.

The short-lived dance between the Illuminati and Freemasons launched a fable that persists among some conspiracy addicts to this day. Various anti-Mason commentators continue to insist that Masters of the Illuminati remain in control of the Freemasons and other secret societies, dedicated to bringing Weishaupt's original plan for world domination to reality. Yet, while the Illuminati appears as a shadowy presence within or among other secret societies, no one seems able to identify specific acts attributable to them. And, unlike every other secret society to be examined here, no one within the Illuminati has ever broken the oath of silence to reveal its inner workings. If you resort exclusively to logic, you suspect that the Illuminati is a phantom organization with neither goals nor members. If you fear secret societies, you believe they are powerful enough to deny their own existence.

FREEMASONS MURDERED U.S. PRESIDENT GEORGE WASHINGTON. According to this theory, Washington resigned from the Freemasons and intended to expose the group's more reprehensible actions to the world. Supposedly, he was outraged at plans by the Masons to erect a monument in his name, in a form that the plotters called an obelisk but the president considered something quite different, referring to it as the Phallus of Baal. To silence the Father of His Nation, so the story goes, he was bled four times by Masonic doctors on the day he died. The Freemasons had already agreed that this would occur on December 31, 1799, the last day of the eighteenth century. In spite of Washington's objections, the phallic Washington Monument was erected, reaching a height of 555 feet—coincidentally equaling the code number signifying assassination in the Luciferian religion.

This fanciful idea is transparent enough to be almost amusing. Bleeding was an accepted medical procedure in the eighteenth century, Washington died December 14, 1799, not December 31, discussions regarding the Washington Monument did not begin until at least a week after his death, and no credible reference exists regarding either a Luciferian religion or its use of 5 as a symbol of death and 555 as a code for assassination.

THE STREETS OF WASHINGTON DC DEPICT MASONIC AND SATANIC SYMBOLS. Like most of his colleagues, architect Pierre Charles L'Enfant was a Freemason when asked to design the seat of federal government in Washington D.C. in 1791. Various sources claim L'Enfant was pressured by both Washington and Jefferson to create a series of satanic occultic symbols representing Freemasonry and labeling its dominance over American politics forever. Among the symbols impressed on Washington's street layout are the evil pentagram, the classic Mason pyramid and a representation of the devil himself, all of them declaring the evil intentions of Freemasons and their absolute power over the United States.

The absurdity of such claims should be self-evident. The pentagram is not a uniquely evil symbol, nor does it play any role in Freemasonry documentation. Moreover, how could its presence make any impact on U.S. affairs, let alone global concerns? Triangles—pyramids are three-dimensional forms that cannot be replicated on street plans—can be traced in the street plan of any community anywhere in the world, and the claimed replication of Satan might be at home in a kindergarten art class, but not among mature adults.

FREEMASONS MURDER THOSE WHO THREATEN TO REVEAL SECRET POLICIES AND AGENDA. Not much is known about William Morgan, but it can be assumed that he was a man of many faults. Born in 1774 in Culpepper County, Virginia, he and his young wife moved to Canada, where they launched a distillery. A mysterious fire destroyed the operation, driving Morgan back to the U.S., where he settled in upstate New York and, after several failed attempts, managed to join the Freemasons. When he was turned down for membership in a new Freemason chapter in Batavia, N.Y.—he was accused, with some justification, of being a swindler—he took revenge by writing and publishing a book attacking Freemasonry. This launched a long chain of events starting with a mysterious fire in the print shop that produced the book, the imprisonment of three Freemasons charged with arson, a series of arrests involving threats against Masons made by Morgan, and an ongoing battle between him and the organization.

In an effort to prove Freemasonry's dominance of U.S. life, theorists find satanic images in the street plan of Washington D.C.

Morgan vanished in 1826, an event that apparently pleased most local residents who hoped life would return to normal. A month later, when a badly decomposed body was found floating in Lake Ontario, many citizens claimed it was Morgan's remains. His wife first denied it was her husband, then admitted it was, and finally denied it again before fleeing New York to become one of several wives claimed by Joseph Smith, founder of the Mormon Church. Later, witnesses reported that Morgan was seen in Boston, Quebec City and other locations, having assumed a new identity and a new wife.

Whoever the floating corpse belonged to, the incident was enough to fuel claims that Morgan had been prepared to reveal deep, dark secrets of Freemasonry activities not mentioned in his book. Nothing captures the public's imagination like a good mystery, especially one that defies solution, and the mystery of William Morgan has been durable enough to support a belief in murderous Masons for almost 200 years.

FREEMASON RITUALS ARE SATANIC AND SUBVERSIVE. To many people who do not share the fraternal goals of Freemasons, a more accurate description of their rituals might be silly and juvenile.

Masons chart their status by degrees ranging from 1 to 33, the 33rd Degree representing the pinnacle of personal achievements as a Mason. The 1st Degree, conferring membership, is granted after the initiate dresses in a particular fashion, submits to a blindfold, and is led to a locked door. His knock on the door and its entry to him symbolize his departure from the out-side world and access to the Inner Sanctum of Freemasonry. After answering questions about his ability to follow Masonic principles, and promising never to reveal the organization's secrets, the initiate experiences the point of a compass being pressed against his chest, and he is asked, “What do you desire?” With the ritualistic reply “More light,” the blindfold is removed and the applicant can see his fellow members for the first time, again very symbolic.

Silliness is carried to extreme by Shriners, a group within Freemasonry whose origins date back to the late nineteenth century. Shriners just wanta-have-fun, and they justify their antics by performing charitable work on behalf of children's hospitals. Recently, their image has been tarnished by revelations suggesting that barely 25 percent of their $8 billion charity endowment is spent on actual charitable activities.

FREEMASONS ARE ADEPT AT DECEIVING THE PUBLIC. “Deceiving” in this case means “hoodwinking,” and for once the charge is true, even if the reality is not what it appears.

The initiation ceremony that includes covering the candidate's eyes during interrogation originally involved placing a hood over his head. “Wink,” an archaic term for “eye,” was associated with this procedure; thus, initiates were said to be “hoodwinked.” Over the years, the meaning of the term has evolved to indicate a deception, spawning the claim that Freemasons consistently present themselves as something they are not.

The early success of Freemasons produced critics, who feared the aggregate power of so many Masons holding high political office, and imitators such as the Oddfellows, who adapted secret procedures of the Masons while ignoring their pseudo-historical and mystical origins.

Among the most vociferous of Masonry critics has been the Catholic Church, launching levels of enmity and suspicion between Masons and Catholics almost from the beginning. As early as 1738, Pope Clement xii condemned Freemasonry, saying, “We command to the faithful to abstain from intercourse with those societies… in order to avoid excommunication, which will be the penalty imposed upon all those contravening this order.” Obviously the Church wasn't merely annoyed; it was outraged and, perhaps, threatened.

A few years later Clement's successor, Benedict xiv, identified six dangers Freemasonry posed to Catholics: (a) the Interconfessionalism (or Interfaith) of Freemasons; (b) their secrecy; (c) their oath; (d) their opposition to church and state; (e) the interdiction pronounced against them in several states by the heads of such countries; and, (f) their immorality.

This is no mere academic or theological difference; for almost 300 years the Catholic Church has practically equated Masons with a stampede of Satans. Leo xiii, in the late nineteenth century, described Masonic lodges as “Bottomless Abysses of Misery which was [sic] dug by those conspiring Societies in which the Heresies and Sects have, it may be said, vomited as in a privy, everything they held in their insides of Sacrilege and Blasphemy.” Obviously, Leo's concept of Christian charity had its limits.

This eighteenth-century acrimony is not diluted by twenty-first-century enlightenment, nor is it limited to traditional Catholic animosity. In November 2002 the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr. Rowan Williams, condemned Masonry as incompatible with Christianity due to its secrecy and “possibly Satanically-inspired” beliefs. An earlier statement by the U.S. Southern Baptist Convention accused Masons of conducting pagan rituals based on the occult, leading the 16-million-strong assembly to brand Masonry as “sacrilegious.”

Religious leaders are not the only people quick to condemn Masons. From a secular point of view, Masonry is also susceptible to charges of racial segregation and gender bias. Corners of the movement continue to maintain separate white and black lodges, with many white groups resisting not only integration but full recognition of their black brethren. They conveniently ignore the fact that black Masons have included, in addition to Duke Ellington, such celebrated individuals as singer Nat “King” Cole, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, author Alex Haley, and political gadfly Reverend Jesse Jackson among their members.

Both black and white members dismiss any suggestion that Masons admit women to their membership rosters, as the Rotary Club has since been ordered to do by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1987. “Freemasonry is a fraternity,” sputtered Douglas Collins, a Texas Mason with Worshipful Master status. “‘Frater’ meaning male brothers. Period. Any mainstream grand lodge in the United States that pulls that stunt [allowing women], they're going to be dropped from fraternal relations by the rest of them. They're going to be an outcast grand lodge.”

Or maybe it will all die away on a rapidly shrinking vine. Membership in all service clubs for men peaked during the 1920s and 1930s in North America, entering a long decline in the years after World War ii. During the 1960s, the number of U.S. Masons was estimated at 4 million; by the year 2000 it had declined to about 1.8 million as society turned away from lodges in pursuit of other means of group identification such as professional sports teams and musical groups. In numbers, and especially in power, Freemasons are a shadow of the organization that wielded influence through the nineteenth and much of the twentieth centuries.

Despite their shrinking numbers and lower profile, Freemasons are still considered by some to be a threat to the world generally and the U.S. in particular, and they remain for many people the first organization that comes to mind when asked to define a “secret society.” Yet, how secret can an organization be when its various meeting places are clearly identified along with its more prominent members? And how deadly can the intentions of a secret society be when it boasts among the highest-ranking members in its history the great Duke Ellington, one of the least likely candidates for performing anything more subversive than a piano solo?

The distant association of Freemasons with Templars and Illuminati, along with the large number of members who have held high political office, fuels wild assumptions among those inclined to assume that anything concealed must, by definition, be evil. Yet this is nothing but extreme speculation. Almost no one claims evil deeds or intentions for the Shriners, elevated Masons whose antics may be tiresome to some, and whose charitable activities may be less all-embracing than its members suggest.

The mainstream media rarely address negative aspects of Masonry or claims of the global powers attributed to it. In fact, media coverage of Freemasonry occurs only in response to shocking events such as an incident that took place in the basement of a Long Island Masonic lodge in March 2004. On that evening William James, 47, gathered at the lodge with about a dozen confirmed Masons to initiate him into the order. Knowing the process would be designed both to frighten him and build confidence in his lodge brothers, James arrived that evening filled with excitement and anticipation.

After enduring the blindfolded knock at the lodge door and the request for “More light!” James was asked to place his nose alongside a mock guillotine. When the guillotine left his nose intact, he was ordered to step carefully among several scattered rat traps, followed by walking a plank.

Nothing surprising occurred until the most dramatic part of the ceremony, which consisted of James being set in front of a shelf holding two empty tin cans. At a signal, a Masonic brother was to fire a pistol in James's direction, and the two tins cans would tumble noisily from the shelf, convincing James that the gun had actually been loaded.

The shots were to be fired by 77-year-old Albert Eid, who arrived for the ceremony carrying a .22 caliber revolver in one pocket and a .32 caliber revolver in the other. The smaller pistol was loaded with blank cartridges, the .32 with real bullets. At a signal from one of the brothers Eid reached into his pocket, withdrew a pistol and, instead of aiming it at the empty tin cans, he pointed it directly at William James and fired. He had chosen the wrong pistol. The bullet entered James's head and he died instantly.

Freemason leaders quickly distanced themselves from the tragedy, noting that the procedure had nothing to do with true Masonic traditions or ceremonies. Anti-Freemasons had little to say at first. After such a tragedy, how could anyone seriously consider the Masons a dangerous society? Then came the revisionists. Within a year, stories circulated on the Internet and elsewhere that James's death had been no accident at all. Eid had been ordered to eliminate James because the about-to-be-initiated Mason had planned to infiltrate the organization and reveal its true clandestine activities. Ignoring the fact that Eid was one of James's oldest and closest friends, and thus the least likely person to be assigned the murder, theorists pointed to the gentle manner with which Eid was treated by the courts, who called the death a senseless tragedy and handed down a five-year suspended sentence. This, they said, was proof that Masons controlled both the media and the justice system.

A new legend was born. If Freemasons endure for a few more centuries, William James may well be associated with William Morgan as another tragic victim of the Freemasons and the machinations of their secret society.