So, you say you don’t like insects? Well, then – maybe you don’t like chocolate, marzipan, apples or strawberries either. The fact is that these and countless other foodstuffs can only be produced in the quantities and quality to which we are accustomed with the help of insects. What we are talking about here, of course, is insects’ work in the field of pollination.

Insect visits to flowers contribute to seed production in more than 80 per cent of the world’s wild plants, and insect pollination improves fruit or seed quality or quantity in a large proportion of our global food crops. Although wind-pollinated crops (such as rice, corn and various other grains) account for the majority of our energy intake, insect-pollinated fruits, berries and nuts are important energy boosters, as well as being a vital source of variety in our diet. We know that the species richness of wild pollinating insects matters, too: a study of 40 different crops across the planet showed that visits from wild insects increased crop yields in all systems.

And we are cultivating a steadily increasing number of crops that require pollination – according to the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), the volume of such crops has tripled over the past 50 years – but the occurrence and species diversity of wild pollinating species is simultaneously declining.

Some pollination also results in a by-product, and one in particular that we all know and love is honey – a natural sweetener with a long history. And if you fancy supplementing your diet with a spot of environmentally friendly protein, why not eat the insects themselves? They’re packed with nourishment and form part of a normal human diet in most areas of the world – except the West.

In this chapter, we’ll take a closer look at insects’ role in our food supply.

Sweet Stuff Steeped in History

We love sweet stuff! The UK’s average per capita sugar consumption currently stands at around 35 kilos per year. This is hardly surprising because the difficulty we humans have in resisting a bowlful of sweets is deeply ingrained in us. Once upon a time our ape ancestors sprinted their shaggy way around Africa eating fruit. Since the sweetest, ripest fruit had the highest energy content, we gradually evolved a preference for sweetness. Back then, before the days of pick-and-mix counters, it simply made sense to have a sweet tooth.

Anybody who has ever accidentally left a banana in a gym bag knows that ripe fruit has an extremely short shelf life. But there is another source of sweetness that is much less perishable and has long been in use: honey. In 2003, construction work on Europe’s second-longest oil pipeline unearthed honey jars in the 5,500-year-old grave of a woman in Georgia.

So, what exactly is honey? It is created when bees extract nectar from flowers, collecting it in a honey sac – a special pouch that lies between the oesophagus and the stomach. This prevents the nectar that will later become honey from mingling with the food passing through the bees’ digestive system. Once inside the honey sac, the nectar mixes with the bees’ enzymes. When the bees return to the hive, they regurgitate the contents of their sac, passing it on to other bees, who store it in their own honey sacs, transport it further into the hive and regurgitate it into the mouths of yet more bees. In the end, the honey is stored in wax cells, where it remains for later use – or until we humans harvest it.

Hallucinogenic Honey

In the Spider Cave (Cuevas de la Araña) in Valencia, Spain, 8,000-year-old cave paintings depict the harvesting of wild honey. They show a man dangling from a rope or vine surrounded by swarming bees, one hand holding a collecting basket and the other inside the nest.

In Asia, vestiges of bee- and honey-based cultures still persist in the food as well as the culture and economy. Twice a year the honey hunters in the foothills of the Himalayas harvest the honey of the Himalayan giant honeybee (Apis dorsata laboriosa), the world’s largest honeybee. It is a hazardous venture, which involves climbing up high cliffs using ladders and ropes amid the buzz of cantankerous bees. These days, pressure from tourists keen to witness the phenomenon is causing over-harvesting of the bee colonies; at the same time, erosion and the shrinkage of wilderness areas are altering the surrounding landscape, all of which are having adverse consequences for the bees. Furthermore, it did little to diminish attention levels when journalists discovered that one variant of the honey gathered in the mountains of Nepal had hallucinogenic properties. The reason for this is that the bees gather poisonous nectar from plants such as rhododendrons and bog rosemary or related heather plants. As a result, the honey may contain a poison called grayanotoxin, which not only affects your pulse and makes you dizzy and nauseous, but can also cause hallucinations.

In fact, ‘mad honey’ is a recognised phenomenon even in Europe. Accounts from antiquity tell of a disastrous military campaign in around 400 BCE, during which thousands of Greek soldiers retreating through present-day Turkey helped themselves to some wild honey. Despite the absence of enemies, their camp soon resembled a battlefield. According to the Ancient Greek military commander and writer Xenophon, the soldiers raved like drunkards, quite out of their wits. Diarrhoea and vomiting rampaged through the camp and only some days later were the men fit enough to struggle to their feet and resume their homeward march.

Other sources from antiquity describe the use of hallucinogenic honey as a weapon of war. A few wax honeycombs of rhododendron honey are ever so casually placed in the enemy’s path – for who can resist a spot of the sweet stuff when they happen to stumble across it? The intoxicated soldiers are then easy to pick off.

This kind of honey is still produced in parts of Turkey, where it is known as deli bal. But there’s no need to worry about poisoning yourself by eating ‘mad honey’. Fortunately, it’s rare for the concentration in the modern, commercially produced honey to be high enough to have ill effects.

Beyond that, honey has long been prized for its antibacterial properties. Historically, it was used on wounds, and it is said that when Alexander the Great died in Babylon, aged just 33, he was submerged in a honey-filled coffin to preserve his body over the two years it would take to transport him to his burial place in Alexandria. The truth of this story is difficult to establish.

The Sweet Taste of Teamwork

One story that is certainly true, however, despite sounding pretty incredible, is the tale of a bird called the greater honeyguide (with the apt Latin name Indicator indicator). This African species helps us humans to find honey. The honeyguide is fond of both honey and wax and wouldn’t say no to a smattering of bee larvae either, and is famous for its unique behaviour. As the name suggests, it can tell other animals and humans where to find honey. In return, it counts on receiving a share in the booty once the nest is broken up by something larger and stronger than itself.

Whereas most birds fly away on our approach, the opposite happens with the honeyguide. It seeks out humans, twitters, and then flies a little way off to see if they’re following. New research has shown that the birds respond to certain human sounds. The Yao are a tribe in Mozambique who still find honey in collaboration with the honeyguide. When the scientists played recordings of the Yao people’s special calls aloud, this increased both the probability that the honeyguide would appear and the probability of it leading them to the bee’s nest. The overall probability of finding honey rose from 16 to 54 per cent. This is one of very few examples of mutual, active collaboration between wild animals and humans.

We have known of this peculiar collaboration since the 1500s, but some anthropologists think it may go all the way back to the days of Homo erectus. In that case, we’re talking 1.8 million years. That tells you a bit about how sought-after this product of the insect world has been for both animals and human beings for thousands of years.

Manna, the Miracle Food

Insects have other sweet titbits to offer too. And they could well be the origin of manna, the miracle food mentioned in the Bible – unless we think of it as a purely miraculous product, that is. According to the Old Testament, manna was the food the Israelites survived on during their journey from Egypt to Israel. This was something of a trip: a 40-year expedition through the barren Sinai Peninsula with few opportunities to lay their hands on food.

That precise thought also struck the Israelites: ‘And the children of Israel said to them, “Oh, that we had died by the hand of the Lord in the land of Egypt, when we sat by the pots of meat and when we ate bread to the full! For you have brought us out into this wilderness to kill this whole assembly with hunger”.’

But the Lord, who had already taken care to equip the world with ‘everything that creeps on the Earth’ in the Book of Genesis, had a solution: ‘“Behold, I will rain bread from heaven for you.” And when the layer of dew lifted, there, on the surface of the wilderness, was a small round substance, as fine as frost on the ground. So when the children of Israel saw it, they said to one another, “What is it?” For they did not know what it was. And Moses said to them, “This is the bread which the Lord has given you to eat.” And the house of Israel called its name Manna. And it was like white coriander seed, and the taste of it was like wafers made with honey. And the children of Israel ate manna for forty years, until they came to an inhabited land.’ (All quotations from Exodus 16, New King James Version of the Bible.)

A slightly monotonous diet perhaps: 40 years of nothing but honey wafers would be enough to cure the sweetest tooth. However, it seems to have been satisfactory hiking food because the Israelites did reach their destination, after all. But are there any natural edible products in this part of the world that might have inspired the description of manna, the miracle food?

Proposed answers, with varying degrees of probability, range from the sap of various bushes or trees, such as the manna ash (Fraxinus ornus), to hallucinogenic mushrooms (Psilocybe cubensis), fragments of lichen (manna lichen or Lecanora esculenta) or algae scum (Spirulina) carried by the wind, to mosquito larvae, tadpoles or other aquatic animals whisked away by tornadoes.

The strongest hypothesis is that manna may have been crystallised honeydew from a sap-sucking insect, specifically the Tamarisk manna scale (Trabutina mannipara). This little insect belongs to the scale insect family and sucks sap from the tamarisk tree (Tamarix genus), which grows extensively across the Middle East.

Because the sap sucked up by the manna scale (and many other sap-sucking insects, see here) is much heavier on sugar than nitrogen, the insects have to jettison the surplus sugar. They do this by excreting a sugary secretion called honeydew. Large quantities of the sweet substance can accumulate on the tamarisk trees and dry into sugar crystals. People in Iraq and other Arab countries still gather these lumps of sugar from tamarisk trees and consider them a delicacy.

If this is the origin of the biblical manna, we might imagine that the wind loosened the crystals and sprinkled them on the earth, making it appear that sugar crystals were raining from the heavens.

Marathon Food

Perhaps the Israelites ought to have taken some hornet juice with them on their long and arduous journey too. It has been shown that the larvae of an Asian hornet produce a substance that is nowadays marketed as a miracle product to boost sporting endurance and performance.

Adult hornets cannot eat solid protein. So instead, they fly home to the nest and feed their larvae small chunks of meat. The larvae have mouths with teeth in and can chomp away. In exchange for these chunks of meat, the larvae regurgitate a kind of jelly that the adults then slurp up.

Once people grasped that the contents of this jelly were crucial for the adult hornet’s endurance – they can fly 100 kilometres a day at a speed of 40kph – it wasn’t long before commercial products aimed at athletes came on the market. Do they work? Debatable. But they certainly sell. Especially since Japanese long-distance runner Naoko Takahashi won the Olympic gold medal for the women’s marathon in Sydney in 2000 and gave much of the credit for her victory to the hornet extract. Sales really took off then! Today, you can buy sports drinks containing hornet larva extract in Japan, and similar products have also caught on in the US.

Billions of Starving Locusts

Sometimes insects simply eat our food. Locust swarms have been – and remain – a feared example of just that. In the Bible, swarms of locusts are described as one of the 10 plagues God inflicted upon Egypt.

So Moses stretched out his rod over the land of Egypt, and the Lord brought an east wind on the land all that day and all that night. When it was morning, the east wind brought the locusts. And the locusts went up over all the land of Egypt and rested on all the territory of Egypt. They were very severe; previously there had been no such locusts as they, nor shall there be such after them. For they covered the face of the whole Earth, so that the land was darkened; and they ate every herb of the land and all the fruit of the trees which the hail had left.

Exodus 2: 10: 13–15,

New King James Version

One fascinating aspect of this biblical quotation is that it remains accurate to this day in strictly ecological terms. Only when the khamsin, a warm south-easterly wind, has blown for at least 24 hours can swarms of locusts reach Egypt from the areas where they originate further east.

And it is a truly terrible sight. A single locust can eat its own bodyweight in food every day. And once we grasp that a swarm can contain 10 billion of these starving, flying, jumping creatures, distributed over an area about the size of Liverpool, we begin to understand how the sky would be darkened, and why they left not a single stalk of grass behind them.

Locust swarms still appear at irregular intervals, mainly in Africa and the Middle East, although estimations indicate swarms are capable of affecting up to 20 per cent of the Earth’s land surface. The mechanism behind locust plagues is like a one-way version of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Normally, the locust is a nice and shy creature, and does not cause any harm to crops. But when special weather conditions make their numbers surge, space becomes tight and they repeatedly bump into each other, which triggers a hormone that changes both the way they look and the way they behave, in a matter of hours. They grow bigger, darker and hungrier, and all of a sudden feel strongly attracted to one another. Large bands of restless locusts form, moving across the landscape and meeting up with other bands to form even bigger groups. One theory is that starvation can lead to cannibalism in locusts and that the swarming behaviour has evolved as an alternative.

Yet the fact that insects eat plants we ourselves want to eat is not solely negative. Many food crops we prize for their acidic, bitter or strong taste have developed these flavours as a defence against grazing, by insects among other creatures. Think of herbs like oregano (see here), or the peppermint tea you’re so fond of, or the mustard you squeeze on your hotdog. If the plants no longer needed a defence, they would spare their resources for other purposes and the taste might change. Many of the active ingredients in medicines extracted from plants may have originated from the plants’ need to avoid being eaten by insects and larger animals.

Chocolate’s Tiny Best Chum

We humans love our chocolate! Worldwide consumption is steadily rising and Britons polish off more than 8 kilograms of the stuff a year. At the same time, producers now warn of a possible shortage in the near future, citing global causes such as climate change and increased consumption in countries like China and India. But there’s actually one teensy-weensy factor nobody is discussing that is crucial to ensuring your access to chocolate; a little midge, in fact, smaller than the head of a pin. Friendless and nameless in English. But perhaps it isn’t so easy to make friends when you’re the size of a poppy seed and all your relatives are blood-sucking jerks. Because the midge in question belongs to the family of biting midges, those teeny insects known in the US as ‘No-See-Ums’ that crawl through your mosquito net and find their way into your ears and behind your glasses, and just can’t resist a few drops of warm blood.

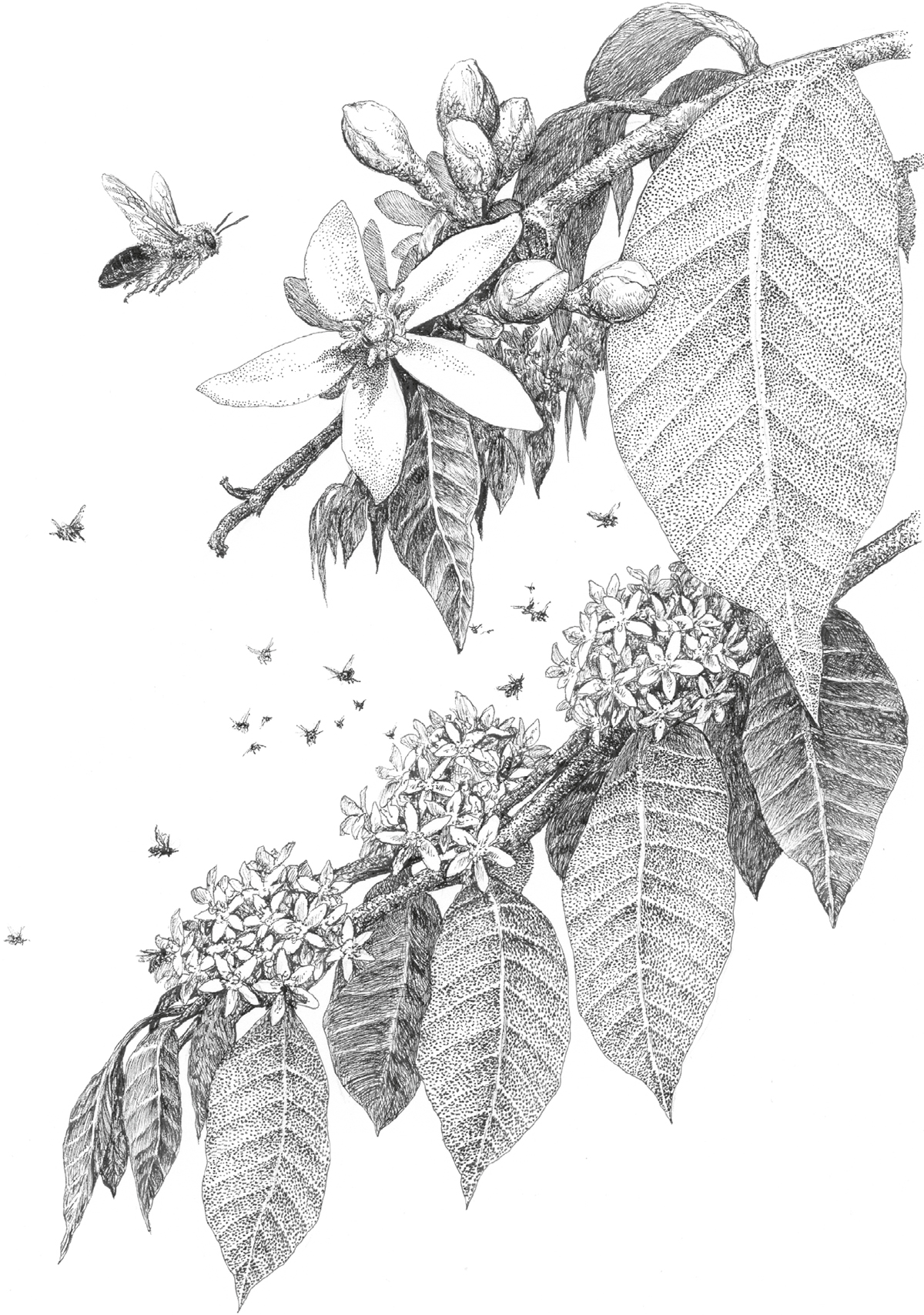

Despite all that, this tiny insect is almost single-handedly responsible for the coating on your digestives, the chocolate bar that sweetens your hike and the cup of cocoa that warms your bones on a chilly winter’s day. Because out in the rainforests, this relative of the biting midge – the chocolate midge – has foregone blood in favour of a lifetime spent crawling in and out of cacao flowers.

These beautiful blossoms, which grow straight out of the stem of the cacao tree, are very intricately constructed. The chocolate midge is one of the few insects that can be bothered – and is small enough – to crawl into a cacao flower and get the pollination done.

But the romantic relationship between the cacao tree and the chocolate midge is complicated because it won’t do to use pollen from another flower on the same tree: no, pollination requires the right stuff, from a neighbouring tree. If you consider that our new insect friend can barely carry enough pollen to pollinate a single flower, is bad at flying and that the flowers only last a day or two before falling off, you’ll get an idea of just how tough this particular relationship is.

In addition, the chocolate midge has certain stipulations when it comes to the fittings in its home: it needs shade and high humidity, and a layer of rotten leaves on the floor of the nursery. This is because its larvae develop in humid compost on the floor of the rainforest.

So, this process doesn’t produce a great deal of cacao – even less so when the growing is done in open plantations that are too dry and too far from the shade for the midge’s liking. Only three out of 1,000 cacao flowers in plantations are successfully pollinated and go on to become mature fruit. On average, a cacao tree produces enough cacao beans for barely 5 kilograms of chocolate in its entire 25-year lifetime.

To convert that into a more recognisable currency, this means that three months’ worth of the entire production of a single cacao tree is required to produce, say, a KitKat. Plus, the hard work of pollination done by hordes of industrious chocolate midges.

Marzipan’s Midwife

Marzipan is simple: just take some finely ground almonds and icing sugar, and add a smidgeon of egg white to bind it all together. Yet marzipan owes its existence to a pretty complicated ‘birth’ that takes place in sunny California.

Eighty per cent of the world’s almond production comes from the Golden State, where the climate is ideally suited to intensive production so farmers exploit the area to the max. Long rows of almond trees cover an area roughly the size of Hampshire in the UK.

The almonds are harvested in September using a mechanical shaking machine that shakes every single tree to make the almonds tumble down. They are then left to lie on the ground for a few days to dry before being swept together and sucked up by an oversized vacuum cleaner that drives between the trees. And now we’re getting to the root of the problem: ideally, there should be nothing between the almond trees but bare, hard-packed earth as this improves both efficiency and almond hygiene. However, it also means that natural flower pollinators such as bees and other insects can find nothing to eat for miles around – pretty tricky considering that almond trees rely on pollination to produce almonds. This explains the massive moving operation that takes place in the US each February. Honeybees are needed on site, so more than a million beehives are transported on specially constructed trucks from all over the US, like some vast NATO exercise. More than half of all the country’s beehives can be found in California every spring, just so you and I get to enjoy our marzipan.

So, the next time you’re chomping on a chunk of marzipan, send a few friendly thoughts in the direction of the bees – marzipan’s midwives.

Beans, Bees and Bowel Movements

Coffee has many functions. It can give you a boost during your break; the coffee machine is an indispensable hub of workplace socialising, and a cup of coffee is a crucial morning pick-me-up for many people, myself included.

Legend has it that an Ethiopian goatherd was the first person to discover the stimulating effect of coffee. He noticed that after eating the red coffee beans his usually grumpy goats began to gambol around joyfully – and so did he when he tried them himself. One day, a passing monk managed to work out the connection. Hey presto! He was suddenly able to stay awake through even the lengthiest prayer services.

Although this may not necessarily be the whole and unvarnished truth about the origin of coffee drinking, what is undeniable is that we are continually learning more about the role different animal species can play in ensuring that our beloved coffee finds its way to our cup. But we’re talking here about animals that are considerably smaller – or a great deal larger – than a goat.

Let’s start with the tiny insects. It seems that even though the most common coffee plant can sort out pollination for itself inside each flower, the coffee crop is much higher if the bushes exchange pollen. And since the coffee flower blossoms for an extremely short time, nothing works better than a grain of pollen delivered straight to the door by express mail. Or straight to the stigma, to use the correct botanical term for the female part of the flower.

And who are the couriers? Many different varieties of bee. Studies show that bees can increase the coffee yield by up to 50 per cent.

In areas where the honeybee has not been introduced, more than 30 different species of solitary bees work amid the coffee flowers. Solitary bees are species where every female takes sole responsibility for her own children – unlike social bees, where most individuals are sterile but help bring up the queen’s offspring.

Social bees like honeybees are also good at pollinating coffee, so coffee producers used to be encouraged to keep colonies of these bees near their coffee plantations. However, the prevailing view nowadays is that introducing honey bees may displace diverse solitary bees, who do a better job overall.

In order for solitary bees to thrive, it is important for there to be enough nesting places for them near the coffee plantation. Some species need small patches of bare earth for their nest, while others live in hollows in old or dead trees. The traditional method of cultivating coffee – in small fields of coffee bushes surrounded by woodland – is a far better way of ensuring pollination than a plantation in full sunlight. What’s more, shade-grown coffee tastes better.

© Carim Nahaboo 2019

And while we’re on the subject of flavour, did you know that the world’s ultimate luxury coffee is really crappy, in the literal sense of the word? When a coffee bean passes through an animal’s intestines, some of the components are broken down and the coffee bean that emerges is sweeter and less bitter.

This remarkable discovery started with the Asian palm civet, a member of the viverrid family. It lives in the tropical rainforests of Indonesia, where it enjoys a varied diet of small animals and fruit, including familiar exotics such as mango, rambutan and – yes, that’s right – the beans of the coffee plant. Don’t ask me who, but somebody struck on the idea of extracting semi-digested coffee beans from the dung of the Asian palm civet and selling them for a stiff price. We’re talking about almost £50 for a cup of civet coffee!

This started off as a nice sideline for small-scale Indonesian farmers, who began to collect wild civet dung. But once people realised there was good money to be made, they started capturing and caging the civets, which were then force-fed coffee beans under miserable conditions. An absolutely wretched business, to be avoided at all costs.

If you must insist on mucking around with £50 cups of coffee, why not go for the elephant-dung variant instead? It’s produced by the Golden Triangle Asian Elephant Foundation, a charitable foundation dedicated to the protection of elephants. Three days after a coffee bean enters at the trunk end, it is picked out of the dung at the tail end, which apparently gives the coffee a raisin-like flavour.

Personally, I’d rather stick to straightforward shade-grown coffee with some raisins on the side!

Redder Strawberries and Better Tomatoes, Thanks to Insects

We have gradually come to realise that insect pollination is crucial for increasing the yield of crops of different fruits and berries, but did you know that insect pollination also helps to improve the quality of the berries?

Take strawberries, for example, which are not berries in strictly botanical terms but so-called false fruit – a swollen, juicy flower base covered in fruits (or actually nuts, botanically speaking, just to complicate matters further). The point is that each of the small pale ‘seeds’ on the outside of a strawberry is actually a tiny fruit, and as many of these as possible must develop in order for the strawberry to become big and juicy. If only a few of these ‘seeds’ develop, the strawberry will be small and knobbly. A well-pollinated strawberry may have 400–500 ‘seeds’ and it takes insects to make that happen.

A German study shows that insect-pollinated strawberries are redder, firmer and less ill-shapen than those that are wind- or self-pollinated. Firmer berries may not only be tastier, but also cope better with transport and storage, meaning they last longer in the shops, and this in turn means the strawberry farmers are better paid for the berries they have grown. The market value of insect-pollinated strawberries was 39 per cent higher than that of wind-pollinated strawberries and as much as 54 per cent higher than that of self-pollinated strawberries.

Similar effects are seen in numerous other insect-pollinated food plants. Apples become sweeter, blueberries bigger, rape seeds have higher oil content, while melons and cucumbers are firmer fleshed. Even where gardeners have run around the tomato greenhouse with a vibrating wand that imitates the quiver of a bumblebee shaking loose the pollen the taste panel is merciless in its judgement: insect-pollinated tomatoes simply taste better.

Food for Our Food

Producing honey and ensuring pollination are not the only useful services insects perform for us and our food, they also form a vital part of the staple diet of the animals many humans like to eat, including larger species such as fish and birds.

Freshwater fish live largely off insects. Because some insects take infant swimming so seriously that they keep their young permanently submerged until they reach the age of reason: mosquitoes, mayflies and dragonflies, to name but a few. Many of the insect babies end up as snacks for trout and perch down there. And then we humans eat the fish. So, you can thank the insects next time you sit down to a trout supper.

Birds are also eager insect-eaters. More than 60 per cent of the world’s bird species are insect eaters. Insects are particularly important as food for the chicks of some species, who are in serious need of protein-rich food to grow big and strong. Some of the birds us humans like hunting and eating, such as pheasants, grouse and ptarmigans, are dependent on juicy insect larvae as chicks.

We humans can use insects as a source of nourishment too. The UN estimates that more than a quarter of the world’s population consumes insects as part of its diet. Insects are most commonly eaten in Asian, African and South American countries, but our European culture also has a certain tradition of this. The Bible provides a precise description of which insects may be eaten – although the understanding of species isn’t quite up to modern-day standards (insects have six legs, not four):

All flying insects that creep on all fours shall be an abomination to you. Yet these you may eat of every flying insect that creeps on all fours: those which have jointed legs above their feet with which to leap on the Earth.

Leviticus 11: 20–21,

New King James Version

This is often interpreted as meaning that orthopterans are fine, while other insects are unclean. And we know that locusts were considered a delicacy in ancient times: stone reliefs from around 700 BCE show skewered locusts being brought out for the king.

Insects Are Healthy, Environmentally Friendly Food

Insects are actually a very nutritious food. Of course, it depends on the type of insect, but generally speaking, they have the protein content of beef with very little of the fat. They also have many other important nutrients: cricket flour may contain more calcium than milk and twice as much iron as spinach. And it’s not just healthy to eat insects, it may be environmentally smart too. Replacing some of our current livestock with mini-livestock such as grasshoppers or mealworm beetles could help make food production considerably more sustainable. For some people, it could also ease the transition to a diet based less on meat and more on plants.

Because, as we know, we’re pressed for space on this planet. There are already more than seven billion of us humans here and 140 newcomers are added every minute. This is equivalent to a net monthly increase the size of the population of Scotland. And when it comes to putting food in all these mouths, insects are a much more efficient option than our traditional domestically farmed animals. It is estimated that, at their best, grasshoppers are 12 times more efficient than cattle at converting fodder to protein.

What’s more, they consume only a fraction of the water a cow does, and produce almost no dung – unlike cows, which really crap on the environment, so to speak. They produce tonnes and tonnes of dung every year, and emit a hefty dose of methane and other climate gases on top of that. There’s very little of that kind of muck in insect dung.

To cut a long story short: insect mini-livestock requires very little space, food and water, reproduces at a tremendous rate, and simultaneously provides an effective source of nutrient-rich food that is high in protein and emits minimal amounts of climate gas.

Could it get any better? Well, yes, actually it could. Because insects can also be raised on our food waste (see here). This means we can kill two birds (or grasshoppers) with one stone, producing good food and eliminating our waste problem at the same time. More research is needed into this area if we seriously intend to include insects in our diet or the diet of our livestock, and this is certainly a growing area of interest. One of the promising initiatives is to farm black soldier fly larvae on food waste. These maggot-like critters are capable of transforming four times their own bodyweight per day into both feed and compost. Harvested in their last larval stage or as a pupae, when their nutritional value peaks, they can be used as feed for fish, poultry, pigs and even dogs. They are also edible for humans and can have a protein content as high as 40 per cent. In addition, the leftover frass (leftover feed, exoskeletons and droppings) from production can be used as fertiliser for plants. As almost one-third of all food produced for human consumption is lost or wasted every year, according to The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), so the potential for alternative solutions here is certainly enormous.

Bug Grub

If using insects for human consumption is to yield any environmental benefits, it won’t be a matter of scattering a few fried ants on our salad, or decorating confectionery with chocolate-coated grasshoppers. Those stunts where people serve up whole insects are mostly just for novelty’s sake.

Just as we don’t eat lamb steak with the wool on, insects will also need to be processed to transform them into tempting foodstuffs. And we must produce them in quantities that make the finished product cheap and easily available. Only then can cricket-flour protein cakes and mealworm burgers become daily fare.

The term ‘Meat-free Monday’ has already caught on. Maybe ‘Insect Tuesday’ will be next?

It may be some time before we start thinking of insects as everyday food in Europe. But how about developing insect-based fodder for livestock or fish in the meantime, using insects that have eaten their way through our organic waste en route to adulthood? That way we could feed our farmed salmon insects instead of soya from Brazil. Research on such topics is happily already underway.

Using insects as food for humans involves some challenges. Insects have their share of parasites and diseases, which we will have to control if we are to engage in large-scale production. Some people have allergic reactions to insects, and legislation dealing with insects for consumption will need upgrading.

Crucially, we must be certain that this is genuinely sustainable, from a lifecycle perspective too – that heating the mini cattle sheds doesn’t eat up all the benefits, for example. Because grasshoppers aren’t like hardy sheep breeds that can be kept outside all year: they won’t necessarily be able to withstand the climate throughout the year without heating, especially in northern climes. Proper heat levels are crucial to rapid growth and high reproduction.

One major challenge remains: consumer acceptance. Consumers must want to buy and eat insect products because they see them as interesting and relevant food. Perhaps this will come about naturally if cheap and tasty insect flour becomes readily available in the shops. Because we can do this if we want to. It only took us a few years to learn to eat raw fish, after all.

Could insects be the new sushi?

It is also important to find the right way to market these new titbits. Grasshoppers and crickets, which people already eat in so many parts of the world, could, with a little imagination, be repackaged as the land’s answer to sea prawns. And we have to use language that sparks positive associations.

Pioneering promoters of the insect diet are on the case. And in the English-speaking world at least, humour seems to be the answer.

Grub Kitchen, a restaurant in Wales, uses punning language to help make the food more palatable – from its name to the often-alliterative offerings on the menu: mealworm macchiato, bug burgers, cricket cookies. Chef Andrew Holcroft has also pointed out that the language used about the dishes must appeal to the senses: ‘Crispy and crunchy descriptions of insects, such as stir-fried or sautéed, sound more appetising than soft-boiled or poached . . . [which sound] squelchy and squishy.’ In Norway, the word mushi has been suggested to promote the softer insect dishes, both to draw on the positive associations of sushi and because it means ‘insect’ in Japanese.

If You Can’t Beat ’Em, Eat ’Em

The nineteenth-century British entomologist Vincent M. Holt was extremely interested in nutrition, especially among Britons of limited means. He thought the working classes should turn to insects as a rich source of nourishment. As early as 1885, the same year in which the Statue of Liberty arrived in New York and Ibsen’s Wild Duck had its world premiere in Bergen, Holt wrote a neat little pamphlet entitled ‘Why Not Eat Insects?’ For the occasion, slugs and snails (which are molluscs) and woodlice (crustaceans) were incorporated in the insect world.

Holt argued forcefully that insects would be a healthy and useful addition to the menu. He thought they would spice up the wretched diet that the working classes and manual labourers ate in those days. The peasant should eat the pests in his field for dinner and the woodman should lunch on the fat larvae in the trees he chopped, he suggested. A win-win situation, in other words.

Holt’s funny little book also includes plenty of recipes. Unfortunately, perhaps, neither his slug soup nor his fried flounder with woodlouse sauce quite caught on. Perhaps a better choice of raw materials and modern methods of preparation might help combat the lack of enthusiasm for eating insects. Nowadays, the matter is under serious discussion at the UN as well as other forums.

Perhaps the future will prove Holt right in the end: ‘While I am confident that they will never condescend to eat us, I am equally confident that, on finding out how good they are, we shall some day right gladly cook and eat them.’