13

The Great Mobilization

There are many things we do not know about the future. But one thing we do know is that business as usual will not continue for much longer. Massive change is inevitable. Will the change come because we move quickly to restructure the economy or because we fail to act and civilization begins to unravel?

Saving civilization will take a massive mobilization, and at wartime speed. The closest analogy is the belated U.S. mobilization during World War II. But unlike that chapter in history, in which one country totally restructured its economy, the Plan B mobilization requires decisive action on a global scale.

On the climate front, official attention has now shifted to negotiating a post-Kyoto protocol to reduce carbon emissions. But that will take years. We need to act now. There is simply not time for years of negotiations and then more years for ratification of another international agreement.

It is time for individual countries to take initiatives on their own. Prime Minister Helen Clarke of New Zealand is leading the way. In late 2007 she announced that New Zealand will boost the renewable share of its electricity from 70 percent, mostly hydro and geothermal, to 90 percent by 2025. The country plans to cut per capita carbon emissions from transport in half by 2040. Beyond this, New Zealand plans to expand its forested area by some 250,000 hectares by 2020, ultimately sequestering roughly 1 million tons of carbon per year. Additional initiatives will be announced in coming months. The challenge, Clarke says, is “to dare to aspire to be carbon neutral.”1

We know from our analysis of global warming, from the accelerating deterioration of the economy’s ecological supports, and from our projections of future resource use in China that the western economic model—the fossil-fuel-based, automobile-centered, throwaway economy—will not last much longer. We need to build a new economy, one that will be powered by renewable sources of energy, that will have a diversified transport system, and that will reuse and recycle everything.

We can describe this new economy in some detail. The question is how to get from here to there before time runs out. Can we reach the political tipping points that will enable us to cut carbon emissions before we reach the ecological tipping points where the melting of the Himalayan glaciers becomes irreversible? Will we be able to halt the deforestation of the Amazon before it dries out, becomes vulnerable to fire, and turns into wasteland?

What if, for example, three years from now scientists announced that we have waited too long to cut carbon emissions and that the melting of the Greenland ice sheet is irreversible? How would the realization that we are responsible for a coming 7-meter (23-foot) rise in sea level and hundred of millions of refugees from rising seas affect us? How would it affect our sense of self, our sense of who we are?2

It could trigger a fracturing of society along generational lines like the more familiar fracturing of societies along racial, religious, and ethnic lines. How will we respond to our children when they ask, “How could you do this to us? How could you leave us facing such chaos?” These are questions we need to be thinking about now—because if we fail to act quickly enough, these are precisely the questions we will be asked.

As we have seen, a corporate accounting system that left costs off the books drove Enron, one of the largest U.S. corporations, into bankruptcy. Unfortunately, our global economic accounting system that also leaves costs off the books has potentially far more serious consequences.

The key to building a global economy that can sustain economic progress is the creation of an honest market, one that tells the ecological truth. To create an honest market, we need to restructure the tax system by reducing taxes on work and raising them on various environmentally destructive activities to incorporate indirect costs into the market price.

If we can get the market to tell the truth, then we can avoid being blindsided by a faulty accounting system that leads to bankruptcy. As Øystein Dahle, former Vice President of Exxon for Norway and the North Sea, has observed: “Socialism collapsed because it did not allow the market to tell the economic truth. Capitalism may collapse because it does not allow the market to tell the ecological truth.”3

Shifting Taxes and Subsidies

The need for tax shifting—lowering income taxes while raising levies on environmentally destructive activities—has been widely endorsed by economists. For example, a tax on coal that incorporated the increased health care costs associated with mining it and breathing polluted air, the costs of damage from acid rain, and the costs of climate disruption would encourage investment in clean renewable sources of energy such as wind or solar.4

A market that is permitted to ignore the indirect costs in pricing goods and services is irrational, wasteful, and, in the end, self-destructive. It is precisely what Nicholas Stern was referring to when he described the failure to incorporate the costs of climate change in the prices of fossil fuels as “a market failure on the greatest scale the world has ever seen.”5

The first step in creating an honest market is to calculate indirect costs. Perhaps the best model for this is a U.S. government study on the costs to society of smoking cigarettes that was undertaken by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In 2006 the CDC calculated the cost to society of smoking cigarettes, including both the cost of treating smoking-related illnesses and the lost worker productivity from these illnesses, at $10.47 per pack.6

This calculation provides a framework for raising taxes on cigarettes. In Chicago, smokers now pay $3.66 per pack in state and local cigarette taxes. New York City is not far behind at $3 per pack. At the state level, New Jersey—which has boosted the tax in four of the last five years to a total of $2.58—has the highest tax. Since a 10-percent price rise typically reduces smoking by 4 percent, the health benefits of tax increases are substantial.7

Tax restructuring can also be used to create an honest pricing system for ecological services. For example, forest ecologists can estimate the values of services that trees provide, such as flood control and carbon sequestration. Once these are determined, they can be incorporated into the price of trees as a stumpage tax. Anyone wishing to cut a tree would have to pay a tax equal to the value of the services provided by that tree. The market for lumber would then be based on ecologically honest prices, prices that would reduce tree cutting and encourage wood reuse and paper recycling.

The most efficient means of restructuring the energy economy to stabilize atmospheric CO2 levels is a carbon tax. Paid by the primary producers—the oil or coal companies—it would permeate the entire fossil fuel energy economy. The tax on coal would be almost double that on natural gas simply because coal has a much higher carbon content. As noted in Chapter 11, we propose a worldwide carbon tax of $240 per ton to be phased in at the rate of $20 per year between 2008 and 2020. Once a schedule for phasing in the carbon tax and reducing the tax on income is in place, the new prices can be used by all economic decisionmakers to make more intelligent decisions.8

For a gasoline tax, the most detailed analysis available of indirect costs is found in The Real Price of Gasoline by the International Center for Technology Assessment. The many indirect costs to society—including climate change, oil industry tax breaks, oil supply protection, oil industry subsidies, and treatment of auto exhaust-related respiratory illnesses—total around $12 per gallon ($3.17 per liter), slightly more than the cost to society of smoking a pack of cigarettes. If this external or social cost is added to the roughly $3 per gallon average price of gas in the United States in early 2007, gas would cost $15 a gallon. These are real costs. Someone bears them. If not us, our children. Now that these costs have been calculated, they can be used to set tax rates on gasoline, just as the CDC analysis is being used to raise taxes on cigarettes.9

Gasoline’s indirect costs of $12 per gallon provide a reference point for raising taxes to where the price reflects the environmental truth. Gasoline taxes in Italy, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom averaging $4.40 per gallon are almost halfway there. The average U.S. gas tax of 47¢ per gallon, scarcely one tenth that in Europe, helps explain why more gasoline is used in the United States than in the next 20 countries combined.10

Phasing in a gasoline tax of 40¢ per gallon per year for the next 12 years, for a total rise of $4.80 a gallon, and offsetting it with a reduction in income taxes would raise the U.S. gas tax to the $4–5 per gallon prevailing today in Europe and Japan. This will still fall short of the $12 of indirect costs currently associated with burning a gallon of gasoline, but combined with the rising price of gasoline itself it should be enough to encourage people to use improved public transport and motorists to buy the plug-in hybrid cars scheduled to enter the market in 2010.

These carbon and gasoline taxes may seem high, but there is at least one dramatic precedent. In November 1998 the U.S. tobacco industry agreed to reimburse state governments $251 billion for the Medicare costs of treating smoking-related illnesses—nearly $1,000 for every person in the United States. This landmark agreement was, in effect, a retroactive tax on cigarettes smoked in the past, one designed to cover indirect costs. To pay this enormous bill, companies raised cigarette prices, bringing them closer to their true costs and further discouraging smoking.11

A carbon tax of $240 per ton of carbon by 2020 may seem steep, but it is not. If gasoline taxes in Europe, which were designed to generate revenue and to discourage excessive dependence on imported oil, were thought of as a carbon tax, the $4.40 per gallon would translate into a carbon tax of $1,815 per ton. This is a staggering number, one that goes far beyond any carbon emission tax or cap-and-trade carbon-price proposals to date. It suggests that the official discussions of carbon prices in the range of $15 to $50 a ton are clearly on the modest end of the possible range of prices. The high gasoline taxes in Europe have contributed to an oil-efficient economy and to far greater investment in high-quality public transportation over the decades, making it less vulnerable to supply disruptions.12

Tax shifting is not new in Europe. A four-year plan adopted in Germany in 1999 systematically shifted taxes from labor to energy. By 2003, this plan had reduced annual CO2 emissions by 20 million tons and helped to create approximately 250,000 additional jobs. It had also accelerated growth in the renewable energy sector, creating some 64,000 jobs by 2006 in the wind industry alone, a number that is projected to rise to 103,000 by 2010.13

Between 2001 and 2006, Sweden shifted an estimated $2 billion of taxes from income to environmentally destructive activities. Much of this shift of $500 or so per household was levied on road transport, including hikes in vehicle and fuel taxes. Electricity is also picking up part of the shift. Environmental tax shifting is becoming commonplace in Europe, where France, Italy, Norway, Spain, and the United Kingdom are also using this policy instrument. In Europe and the United States, polls indicate that at least 70 percent of voters support environmental tax reform once it is explained to them.14

Environmental taxes are now being used for several purposes. As noted earlier, landfill taxes adopted by either national or local governments are becoming more common. A number of cities are now taxing cars that enter the city. Others are simply imposing a tax on automobile ownership. In Denmark, the tax on the purchase of a new car exceeds the price of the car itself. A new car that sells for $25,000 costs the buyer more than $50,000. Other governments are moving in this direction. New York Times reporter Howard French writes that Shanghai, which is being suffocated by automobiles, “has raised the fees for car registrations every year since 2000, doubling over that time to about $4,600 per vehicle—more than twice the city’s per capita income.”15

Some 2,500 economists, including eight Nobel Prize winners in economics, have endorsed the concept of tax shifts. Harvard economics professor N. Gregory Mankiw wrote in Fortune magazine: “Cutting income taxes while increasing gasoline taxes would lead to more rapid economic growth, less traffic congestion, safer roads, and reduced risk of global warming—all without jeopardizing long-term fiscal solvency. This may be the closest thing to a free lunch that economics has to offer.”16

Cap-and-trade systems using tradable permits are sometimes an alternative to environmental tax restructuring. The principal difference between them is that with permits, governments set the amount of a given activity that is allowed, such as the harvest from a fishery, and let the market set the price of the permits as they are auctioned off. With environmental taxes, in contrast, the price of the environmentally destructive activity is incorporated in the tax rate, and the market determines the amount of the activity that will occur at that price. Both economic instruments can be used to discourage environmentally irresponsible behavior.

The use of cap-and-trade systems with marketable permits has been effective at the national level, ranging from restricting the catch in an Australian fishery to reducing sulfur emissions in the United States. For example, the government of Australia, concerned about lobster overharvesting, estimated the sustainable yield of lobsters and then issued catch permits totaling that amount. Fishers could then bid for these permits. In effect, the government decided how many lobsters could be taken each year and let the market decide what the permits were worth. Since the permit trading system was adopted in 1986, the fishery has stabilized and appears to be operating on a sustainable basis.17

Although tradable permits are popular in the business community, permits are administratively more complicated and not as well understood as taxes. Edwin Clark, former senior economist with the White House Council on Environmental Quality, observes that tradable permits “require establishing complex regulatory frameworks, defining the permits, establishing the rules for trades, and preventing people from acting without permits.” In contrast to restructuring taxes, something with which there is wide familiarity, tradable permits are a concept not widely understood by the public, making it more difficult to generate broad public support.18

Each year the world’s taxpayers provide an estimated $700 billion of subsidies for environmentally destructive activities, such as fossil fuel burning, overpumping aquifers, clearcutting forests, and overfishing. An Earth Council study, Subsidizing Unsustainable Development, observes that “there is something unbelievable about the world spending hundreds of billions of dollars annually to subsidize its own destruction.”19

Iran provides a classic example of extreme subsidies when it prices oil for internal use at one tenth the world price, strongly encouraging car ownership and gas consumption. If its $37-billion annual subsidy were phased out, the World Bank reports that Iran’s carbon emissions would drop by a staggering 49 percent. This move would also strengthen the economy by freeing up public revenues for investment in the country’s economic development. Iran is not alone. The Bank reports that removing energy subsidies would reduce carbon emissions in India by 14 percent, in Indonesia by 11 percent, in Russia by 17 percent, and in Venezuela by 26 percent. Carbon emissions could be cut in scores of countries by simply eliminating fossil fuel subsidies.20

Some countries are already doing this. Belgium, France, and Japan have phased out all subsidies for coal. Germany reduced its coal subsidy from $2.8 billion in 1989 to $1.4 billion in 2002, meanwhile lowering its coal use by 38 percent. It plans to phase out this support entirely by 2018. As oil prices have climbed, a number of countries have greatly reduced or eliminated subsidies that held fuel prices well below world market prices because of the heavy fiscal cost. Among these are China, Indonesia, and Nigeria.21

A study by the U.K. Green Party, Aviation’s Economic Downside, describes the extent of subsidies to the U.K. airline industry. The giveaway begins with $18 billion in tax breaks, including a total exemption from the federal tax. External or indirect costs that are not paid, such as treating illness from breathing the air polluted by planes, the costs of climate change, and so forth, add nearly $7.5 billion to the tab. The subsidy in the United Kingdom totals $426 per resident. This is also an inherently regressive tax policy simply because a part of the U.K. population cannot afford to fly, yet they help subsidize this high-cost travel for their more affluent compatriots.22

While some leading industrial countries have been reducing subsidies to fossil fuels—notably coal, the most climate-disrupting of all fuels—the United States has increased its support for the fossil fuel and nuclear industries. Douglas Koplow, founder of Earth Track, calculated in a 2006 study that annual U.S. federal energy subsidies have a total value to the industry of $74 billion. Of this, the oil and gas industry gets $39 billion, coal $8 billion, and nuclear $9 billion. At a time when there is a need to conserve oil resources, U.S. taxpayers are subsidizing their depletion.23

Just as there is a need for tax shifting, there is also a need for subsidy shifting. A world facing the prospect of economically disruptive climate change, for example, can no longer justify subsidies to expand the burning of coal and oil. Shifting these subsidies to the development of climate-benign energy sources such as wind, solar, biomass, and geothermal power will help stabilize the earth’s climate. Shifting subsidies from road construction to rail construction could increase mobility in many situations while reducing carbon emissions. And shifting the $22 billion in annual fishing industry subsidies, which encourage destructive overfishing, to the creation of marine parks to regenerate fisheries would be a giant step in restoring oceanic fisheries.24

In a troubled world economy, where many governments are facing fiscal deficits, these proposed tax and subsidy shifts can help balance the books, create additional jobs, and save the economy’s eco-supports. Tax and subsidy shifting promise energy efficiency, cuts in carbon emissions, and reductions in environmental destruction—a win-win-win situation.

Summing Up Climate Stabilization Measures

Earlier we outlined the need to cut net carbon dioxide emissions 80 percent by 2020 to minimize the future rise in temperature. Here we summarize the Plan B measures for doing so, including both reducing fossil fuel use and increasing biological sequestration.

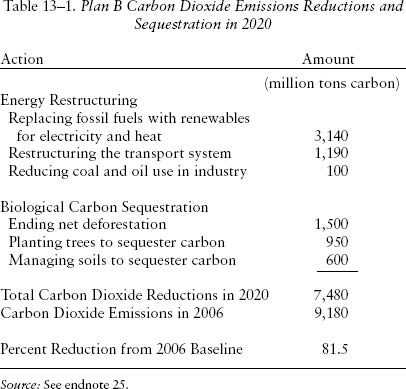

Replacing fossil fuels with renewable sources of energy for generating electricity and heat will reduce carbon emissions in 2020 by more than 3.1 billion tons. (See Table 13–1.) The biggest single cut in carbon emissions comes from phasing out the use of coal to generate electricity, a step that will also sharply reduce the 3 million deaths from air pollution each year. Other cuts come from entirely backing out all the oil used to generate electricity and 70 percent of the natural gas.25

In the transport sector, the greatly reduced use of oil will eliminate close to 1.2 billion tons of carbon emissions. This reduction relies heavily on the shift to plug-in hybrid cars that will run on carbon-free sources of electricity such as wind. The remainder comes largely from shifting long-haul freight from trucks to trains, electrifying freight and passenger trains, and using green electricity to power them.26

At present, net deforestation of the earth is responsible for an estimated 1.5 billion tons of carbon emissions per year. The Plan B goal is to bring deforestation to a halt by 2020, thus totally eliminating this source of carbon emissions. The idea of banning logging may seem novel, but in fact a number of countries already have total or partial bans.27

We’re not content with just halting deforestation. We want to increase the number of trees on the earth in order to sequester carbon. The forestation of wastelands will fix more than 950 million tons of carbon each year. This does not include the similarly ambitious planting of trees to control flooding, reduce rainfall runoff to recharge aquifers, and protect soils from erosion.28

The other initiative to sequester carbon biologically is achieved through land use management. This includes expanding the area of minimum-or no-till cropland, planting more cover crops during the off-season, and using more perennials instead of annuals in cropping patterns. The latter would mean, for example, using less corn and more switchgrass to produce fuel ethanol. These practices can fix an estimated 600 million tons of carbon per year.29

Together, replacing fossil fuels in electricity generation with renewable sources of energy, switching to plug-in hybrid cars, going to all-electric railways, banning deforestation, and sequestering carbon by planting trees and improving soil management will drop carbon dioxide emissions in 2020 more than 80 percent below today’s levels. This reduction will stabilize atmospheric CO2 concentrations below 400 parts per million, limiting the future rise in temperature.30

Although we devoted a chapter to increasing energy efficiency—doing what we do with less energy—there is also a huge potential for cutting carbon emissions through conservation by not doing some of the things we do, or doing them differently. For example, in the summer of 2006 Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi of Japan announced that in order to save energy, Japanese men would be encouraged to not wear jackets and ties in the office. This meant thermostats could be raised, thus reducing electricity use for air conditioning while maintaining the same comfort level.31

Our tabulated carbon cuts do not include lifestyle changes like this, which can make a huge difference. Urban planner Richard Register recounts meeting a bicycle activist friend wearing a T-shirt that said, “I just lost 3,500 pounds. Ask me how.” When asked, he said he had sold his car. Replacing a 3,500-pound car with a 22-pound bicycle obviously reduces energy use dramatically, but it also reduces materials use by 99 percent, indirectly saving still more energy.32

Dietary changes can also make a difference. We learned in Chapter 9 that the energy differences between a diet rich in red meat and a plant-based diet is roughly the same as the energy-use difference between driving a Chevrolet Suburban sports utility vehicle and a Toyota Prius gas-electric hybrid. The bottom line is that those of us with diets rich in livestock products can do both ourselves and civilization a favor by moving down the food chain.33

For countries everywhere, particularly developing ones, the economic good news is that the Plan B energy economy is much more labor-intensive than the fossil-fuel-based economy it is replacing. For example, in Germany, a leader in the energy transition, renewable energy industries already employ more workers than the long-standing fossil fuel and nuclear industries do. In a world where expanding employment is a universal goal, this is welcome news indeed.34

The restructuring of the energy economy outlined here will not only dramatically drop CO2 emissions, helping to stabilize climate, but it will also eliminate much of the air pollution that we know today. The idea of a pollution-free environment is difficult for us even to imagine, simply because none of us has ever known an energy economy that was not highly polluting. Working in coal mines will be history. Black lung disease will eventually disappear. So too will “code red” alerts warning of health threats from extreme air pollution.

And, finally, in contrast to investments in oil fields and coal mines, where depletion and abandonment are inevitable, the new energy sources are inexhaustible. While wind turbines, solar cells, and solar-thermal panels will all need repair and occasional replacement, the initial investment can last forever. This well will not go dry.

A Response to Failing States

If the number of failing states continues to increase, at some point this trend will translate into a failing civilization. These declining states threaten the political stability of the international system. Somehow we must turn the tide of state decline. One thing seems clear: business as usual will not do it.

Failing states, a relatively new phenomenon, require a new response. Historically, as noted in Chapter 1, the principal threat to international stability and the security of individual countries has been the concentration of power in one country. Today the threat to security comes from the loss of power and the descent of nation-states into anarchy and chaos. These failing states become terrorist training grounds (as in Iraq and Afghanistan), drug producers (Afghanistan and Myanmar), and weapons traders (Somalia and Nigeria).

The goals discussed earlier of stabilizing population, eradicating poverty, and restoring the earth are indispensable, but we also need a focused effort to deal specifically with states that are failing or at risk of doing so. The United Kingdom and Norway have recognized that failing states need special attention and have each set up interagency funds to provide a response mechanism. They are the first to devise a specific institutional response.35

At present, U.S. efforts to deal with weak and failing states are fragmented. Several U.S. government departments are involved, including State, Treasury, and Agriculture, to name a few. And within the State Department, several different offices are concerned with this issue. This lack of focus was recognized by the Hart-Rudman U.S. Commission on National Security in the Twenty-first Century: “Responsibility today for crisis prevention and response is dispersed in multiple AID [U.S. Agency for International Development] and State bureaus, and among State’s Under Secretaries and the AID Administrator. In practice, therefore, no one is in charge.”36

What is needed now is a new cabinet-level agency—a Department of Global Security—that would fashion a coherent policy toward each weak and failing state. This recommendation, initially set forth in a report of the Commission on Weak States and U.S. National Security, recognizes that the threats to security are now coming less from military power and more from the trends that undermine states, such as rapid population growth, poverty, deteriorating environmental support systems, and spreading water shortages. The new agency would incorporate AID (now part of the State Department) and all the various foreign assistance programs that are now in other government departments, thereby assuming responsibility for U.S. development assistance across the board. The State Department would provide diplomatic support for this new agency, helping in the overall effort to reverse the process of state failure.37

The new Department of Global Security (DGS) would be funded by shifting fiscal resources from the Department of Defense. In effect, the DGS budget would be the new defense budget. It would focus on the central sources of state failure by helping to stabilize population, restore environmental support systems, eradicate poverty, provide universal primary school education, and strengthen the rule of law through bolstering police forces and court systems.

The DGS would deal with the production and international trafficking in drugs. It would make such issues as debt relief and market access an integral part of U.S. policy. The DGS would provide a focus for the United States to help lead what it can be hoped will be a growing international effort to reduce the number of failing states. This agency would also encourage private investment in failing states by providing loan guarantees to spur development.

The United States might also benefit from the creation of a U.S. youth service corps, which would provide for one year of compulsory public service for its young people. Young people could serve at home or abroad, depending on their interests and on national needs. At home, they could teach in inner-city schools, work on environmental clean-up programs, plant trees, and help restore and maintain the infrastructure in national parks, much as the Civilian Conservation Corps did in the 1930s. In developing countries, they could contribute in many ways, including teaching and helping to organize family planning, tree planting, and micro-lending programs. This program would involve young people in helping the world while developing a sense of civic pride and social responsibility.38

At a more senior level, the United States has a fast-growing reservoir of retired people who are highly skilled in such fields as management, accounting, law, education, and medicine and who are eager to be of use. Their talents could be mobilized through a voluntary senior service corps. The enormous reservoir of management skills in this age group could be tapped to provide the skills so lacking in failing-state governments.

There are already, of course, a number of volunteer organizations that rely on the talents, energy, and enthusiasm of both U.S. young people and seniors, such as the Peace Corps, Teach for America, and the Senior Corps. But conditions now require a much more ambitious, systematic effort to tap this talent pool.

The world has quietly entered a new era, one where there is no national security without global security. We need to recognize this and to restructure and refocus our efforts to respond to this new reality.

A Wartime Mobilization

As we contemplate mobilizing to save civilization, we see both similarities and contrasts with the mobilization for World War II. In this earlier case, there was an economic restructuring, but it was temporary. Mobilizing to save civilization, in contrast, requires an enduring economic restructuring.

Still, the U.S. entry into World War II offers an inspiring case study in rapid mobilization. Initially, the United States resisted involvement in the war and responded only after it was directly attacked at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. But respond it did. After an all-out commitment, the U.S. engagement helped turn the tide of war, leading the Allied Forces to victory within three-and-a-half years.39

In his State of the Union address on January 6, 1942, one month after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt announced the country’s arms production goals. The United States, he said, was planning to produce 45,000 tanks, 60,000 planes, 20,000 anti-aircraft guns, and 6 million tons of merchant shipping. He added, “Let no man say it cannot be done.”40

No one had ever seen such huge arms production numbers. But Roosevelt and his colleagues realized that the world’s largest concentration of industrial power at that time was in the U.S. automobile industry. Even during the Depression, the United States was producing 3 million or more cars a year. After his State of the Union address, Roosevelt met with automobile industry leaders and told them that the country would rely heavily on them to reach these arms production goals. Initially they wanted to continue making cars and simply add on the production of armaments. What they did not yet know was that the sale of new cars would soon be banned. From early 1942 through the end of 1944, nearly three years, there were essentially no cars produced in the United States.41

In addition to a ban on the production and sale of cars for private use, residential and highway construction was halted, and driving for pleasure was banned. Strategic goods—including tires, gasoline, fuel oil, and sugar—were rationed beginning in 1942. Cutting back on private consumption of these goods freed up material resources that were vital to the war effort.42

The year 1942 witnessed the greatest expansion of industrial output in the nation’s history—all for military use. Wartime aircraft needs were enormous. They included not only fighters, bombers, and reconnaissance planes, but also the troop and cargo transports needed to fight a war on distant fronts. From the beginning of 1942 through 1944, the United States far exceeded the initial goal of 60,000 planes, turning out a staggering 229,600 aircraft, a fleet so vast it is hard even today to visualize it. Equally impressive, by the end of the war more than 5,000 ships were added to the 1,000 or so that made up the American Merchant Fleet in 1939.43

In her book No Ordinary Time, Doris Kearns Goodwin describes how various firms converted. A sparkplug factory was among the first to switch to the production of machine guns. Soon a manufacturer of stoves was producing lifeboats. A merry-go-round factory was making gun mounts; a toy company was turning out compasses; a corset manufacturer was producing grenade belts; and a pinball machine plant began to make armor-piercing shells.44

In retrospect, the speed of this conversion from a peacetime to a wartime economy is stunning. The harnessing of U.S. industrial power tipped the scales decisively toward the Allied Forces, reversing the tide of war. Germany and Japan, already fully extended, could not counter this effort. Winston Churchill often quoted his foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey: “The United States is like a giant boiler. Once the fire is lighted under it, there is no limit to the power it can generate.”45

This mobilization of resources within a matter of months demonstrates that a country and, indeed, the world can restructure the economy quickly if convinced of the need to do so. Many people—although not yet the majority—are already convinced of the need for a wholesale economic restructuring. The purpose of this book is to convince more people of this need, helping to tip the balance toward the forces of change and hope.

Mobilizing to Save Civilization

Mobilizing to save civilization means restructuring the economy, restoring its natural support systems, eradicating poverty, stabilizing population and climate, and, above all, restoring hope. We have the technologies, economic instruments, and financial resources to do this. The United States, the wealthiest society that has ever existed, has the resources to lead this effort. Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia University’s Earth Institute sums it up well: “The tragic irony of this moment is that the rich countries are so rich and the poor so poor that a few added tenths of one percent of GNP from the rich ones ramped up over the coming decades could do what was never before possible in human history: ensure that the basic needs of health and education are met for all impoverished children in this world. How many more tragedies will we suffer in this country before we wake up to our capacity to help make the world a safer and more prosperous place not only through military might, but through the gift of life itself?”46

It is not possible to put a precise price tag on the changes needed to move our twenty-first century civilization off the decline-and-collapse path and onto a path that will sustain economic progress. But we can at least provide some rough estimates of the scale of effort needed.

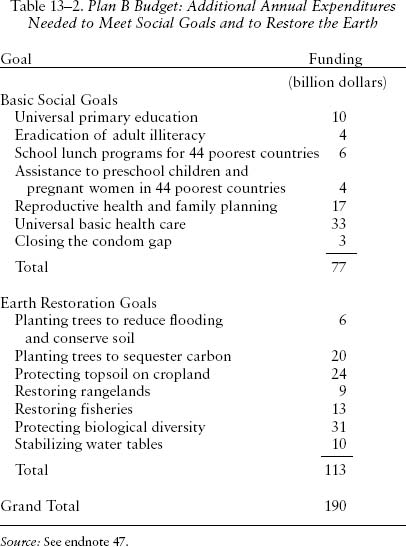

As noted in Chapter 7, the additional external funding needed to achieve universal primary education in developing countries that require help, for instance, is conservatively estimated at $10 billion per year. (See Table 13–2.) Funding for an adult literacy program based largely on volunteers will take an estimated additional $4 billion annually. Providing for the most basic health care in developing countries is estimated at $33 billion by the World Health Organization. The additional funding needed to provide reproductive health care and family planning services to all women in developing countries amounts to $17 billion a year.47

Closing the condom gap by providing the additional 9.5 billion condoms needed to control the spread of HIV in the developing world and Eastern Europe requires $3 billion—$550 million for condoms and $2.75 billion for AIDS prevention education and condom distribution. The cost of extending school lunch programs to the 44 poorest countries is $6 billion. An estimated $4 billion per year would cover the cost of assistance to preschool children and pregnant women in these countries. Altogether, the cost of reaching basic social goals comes to $77 billion a year.48

As noted in Chapter 8, a poverty eradication effort that is not accompanied by an earth restoration effort is doomed to fail. Protecting topsoil, reforesting the earth, restoring oceanic fisheries, and other needed measures will cost an estimated $113 billion in additional expenditures per year. The most costly activities, protecting biological diversity at $31 billion and conserving soil on cropland at $24 billion, account for almost half of the earth restoration annual outlay.49

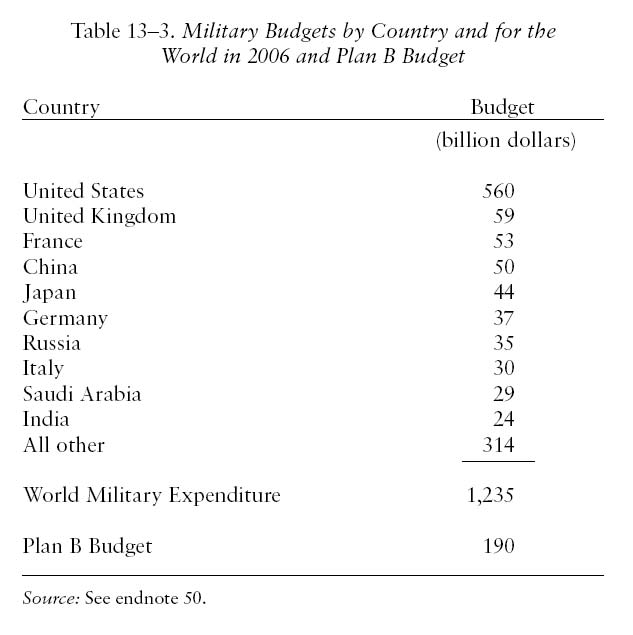

Combining social goals and earth restoration components into a Plan B budget yields an additional annual expenditure of $190 billion, roughly one third of the current U.S. military budget or one sixth of the global military budget. (See Table 13–3.) In a sense this is the new defense budget, the one that addresses the most serious threats to our security.50

Unfortunately, the United States continues to focus on building an ever-stronger military, largely ignoring the threats posed by continuing environmental deterioration, poverty, and population growth. Its defense budget for 2006, including $118 billion for the military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, brought the U.S. military expenditure to $560 billion. Other North Atlantic Treaty Organization members spend a combined $328 billion a year on the military. Russia spends about $35 billion, and China, $50 billion. U.S. military spending is now roughly equal to that of all other countries combined.51

As of late 2007, direct U.S. appropriations for the Iraq war, which has lasted longer than World War II, total some $450 billion. Economists Joseph Stiglitz and Linda Bilmes calculate that if all the costs are included, such as the lifetime of care required for returning troops who are brain-injured or psychologically shattered, the war will cost in the end some $2 trillion. Yet the Iraq war may prove to be one of history’s most costly mistakes not so much because of fiscal outlay but because it has diverted the world’s attention from climate change and the other threats to civilization itself.52

It is decision time. Like earlier civilizations that got into environmental trouble, we can decide to stay with business as usual and watch our modern economy decline and eventually collapse, or we can consciously move onto a new path, one that will sustain economic progress. In this situation, no action is a de facto decision to stay on the decline-and-collapse path.

No one can argue today that we do not have the resources to eradicate poverty, stabilize population, and protect the earth’s natural resource base. We can get rid of hunger, illiteracy, disease, and poverty, and we can restore the earth’s soils, forests, and fisheries. Shifting one sixth of the world military budget to the Plan B budget would be more than adequate to move the world onto a path that would sustain progress. We can build a global community where the basic needs of all the earth’s people are satisfied—a world that will allow us to think of ourselves as civilized.

This economic restructuring depends on tax restructuring, on getting the market to be ecologically honest. The benchmark of political leadership will be whether leaders succeed in restructuring the tax system. Restructuring the tax system, not additional appropriations, is the key to restructuring the energy economy.

It is easy to spend hundreds of billions in response to terrorist threats, but the reality is that the resources needed to disrupt a modern economy are small, and a U.S. Department of Homeland Security, however heavily funded, provides only minimal protection from suicidal terrorists. The challenge is not to provide a high-tech military response to terrorism but to build a global society that is environmentally sustainable and equitable—one that restores hope for everyone. Such an effort would do more to combat terrorism than any increase in military expenditures or than any new weapons systems, however advanced.

Source: See endnote 50.

Just as the forces of decline can reinforce each other, so can the forces of progress. Fortunately, the steps to reverse destructive trends or to initiate constructive new trends are often mutually reinforcing, win-win solutions. For example, efficiency gains that lower oil dependence also reduce carbon emissions and air pollution. Steps to eradicate poverty help stabilize population. Reforestation fixes carbon, increases aquifer recharge, and reduces soil erosion. Once we get enough trends headed in the right direction, they will reinforce each other.

The world needs a major success story in reducing carbon emissions and dependence on oil to bolster hope in the future. If the United States, for instance, were to launch a crash program to shift to plug-in hybrid cars while simultaneously investing in thousands of wind farms, Americans could do most of their short-distance driving with wind energy, dramatically reducing pressure on the world’s oil supplies.53

With many U.S. automobile assembly lines idled, it would be a relatively simple matter to retool some of them to produce wind turbines, enabling the country to quickly harness its vast wind energy potential. This would be a rather modest initiative compared with the restructuring during World War II, but it would help the world to see that restructuring an economy is entirely doable and that it can be done quickly, profitably, and in a way that enhances national security both by reducing dependence on vulnerable oil supplies and by avoiding disruptive climate change.

What You and I Can Do

One of the questions I am frequently asked when I am speaking in various countries is, given the environmental problems that the world is facing, can we make it? That is, can we avoid economic decline and the collapse of civilization? My answer is always the same: it depends on you and me, on what you and I do to reverse these trends. It means becoming politically active. Saving our civilization is not a spectator sport.

We have moved into this new world so fast that we have not yet fully grasped the meaning of what is happening. Traditionally, concern for our children has translated into getting them the best health care and education possible. But if we do not act quickly to reverse the earth’s environmental deterioration, eradicate poverty, and stabilize population, their world will decline economically and disintegrate politically.

The two overriding policy challenges are to restructure taxes and reorder fiscal priorities. Saving civilization means restructuring taxes to get the market to tell the ecological truth. And it means reordering fiscal priorities to get the resources needed for Plan B. Write or e-mail your elected representative about the need for tax restructuring to create an honest market. Remind him or her that corporations that left costs off the books appeared to prosper in the short run, only to collapse in the long run.

Or better yet, gather some like-minded friends together to meet with your elected representatives to discuss why we need to raise environmental taxes and reduce income taxes. Before the meeting, draft a brief statement of your collective concerns and the policy initiatives needed. Feel free to download the information on tax restructuring in this chapter from our Web site to use in these efforts.

Let your political representatives know that a world spending more than $1 trillion a year for military purposes is simply out of sync with reality when the future of civilization is in question. Ask them if $190 billion a year is an unreasonable expenditure to save civilization. Ask them if diverting one sixth of the global military budget to saving civilization is too costly. Introduce them to Plan B. Remind them of how we mobilized in World War II.54

Make a case for the inclusion of poverty eradication, family planning, reforestation, and renewable energy development in international assistance programs. Urge an increase in these appropriations and a cut in military appropriations, pointing out that advanced weapons systems are useless in dealing with the new threats to our security. Someone needs to speak on behalf of our children and grandchildren, because it is their world that is at stake.

In short, we need to persuade our elected representatives and leaders to support the changes outlined in Plan B. We need to lobby them for these changes as though our future and that of our children depended on it—because it does.

Educate yourself on environmental issues. If you found this book useful, share it with others. It can be downloaded free of charge from the Earth Policy Institute Web site. If you want to know what happened to earlier civilizations that also found themselves in environmental trouble, read Collapse by Jared Diamond or A Short History of Progress by Ronald Wright.55

If you like to write, try your hand at an op-ed piece for your local newspaper on the need to raise taxes on environmentally destructive activities and offset this with a lowering of income taxes. Try a letter to the editor. Put together your own personal listserv to help you communicate useful information to friends, colleagues, and local opinion leaders.

The scale and urgency of the challenge we face has no precedent, but what we need to do can be done. It is doable. Sit down and map out your own personal plan and timetable for what you want to do to move the world off a path headed toward economic decline and onto one of sustainable economic progress. Set your own goals. Identify people in your community you can work with to achieve these goals. Pick an issue that is meaningful to you, such as restructuring the tax system, banning inefficient light bulbs, phasing out coal-fired power plants, or working for “complete streets” that are pedestrian-and bicycle-friendly in your community. What could be more exciting and rewarding?

The choice is ours—yours and mine. We can stay with business as usual and preside over an economy that continues to destroy its natural support systems until it destroys itself, or we can adopt Plan B and be the generation that changes direction, moving the world onto a path of sustained progress. The choice will be made by our generation, but it will affect life on earth for all generations to come.