Chapter 2

FROM SPOON TO FLUID BEDS

Roasting History

The discovery that the seeds of the coffee fruit tasted good when roasted was undoubtedly the key moment in coffee history. It marked the beginning of the transformation of coffee from an obscure medicinal herb known only in the horn of Africa and southern Arabia to the most popular beverage in the world, a beverage so widely drunk that today its trade generates more money than any other commodity except oil.

A skeptic might counter that it is caffeine, not flavor (or the roasting necessary to develop that flavor), that made coffee into one of the world’s most important commodities. This argument is difficult to sustain, however. Tea, yerba maté, cocoa, coca, and other less famous plants also contain substances that wake us up and make us feel good. Yet none has achieved quite the same universal success as coffee.

Furthermore coffee—coffee without the caffeine—figures as an important flavoring in countless candies, cakes, and confections. And people sensitive to caffeine happily choose to drink decaffeinated coffee in preference to other caffeine-free beverages.

So clearly the aromatics of roasted coffee have a great deal to do with its triumph. On the other hand, there is evidence that the taste of coffee takes some getting used to. Children do not spontaneously like coffee, for example. And from coffee’s first appearances in human culture to the present, people have tended to add things to it. The first recorded coffee drinkers enhanced the beverage with cardamom and other spices, a tendency that continues today with flavored coffees and espresso drinks augmented with syrups, garnishes, and milk.

More than likely it is both the aromatic characteristics of roasted coffee and its stimulant properties that hooked humanity. At some point people began to associate the stimulating effect of coffee with the dark resonance of its taste, and combined those associations with the myriad social satisfactions that began to cluster around the beverage; coming to consciousness in the morning, hospitality, conversation, the reveries of cafés. Thus the entire package—stimulation, taste, and social ritual—came together to mean coffee in all of its complexity and richness.

Coffee-Leaf Tea and Coffee-Fruit Frappés

We can only speculate how coffee was consumed before the advent of roasting sometime in the sixteenth century. However, the practices of some African societies in the regions where the coffee tree grows wild give us clues.

Ethiopian tribal peoples make tea from the leaves of the coffee tree, for example. Other recorded customs include chewing the dried fruit, pressing it into cakes, infusing it, mashing the ripe coffee fruit into a drink, and eating the crushed seeds imbedded in animal fat.

It is difficult to believe that coffee would have become the beverage of choice of most of the world if the only way to experience it was by infusing its leaves; putting its rather meager, thin-pulped fruit in a blender; or chewing on its raw seeds. Furthermore, there is at least some evidence that coffee’s accelerated success over the past two centuries may be in part the result of continuous improvements in the understanding and technology of roasting, which, inference suggests, have produced an increasingly attractive beverage.

Mysterious Origins

Who first thought of roasting the seeds of the coffee tree and why?

We will doubtless never know. The early history of coffee in human culture is as obscure as the origin of most of the world’s great foods. All that is known is based on inferences drawn from a few scattered references in written documents of the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Middle East.

When European travelers first encountered the beverage in the coffeehouses of Syria, Egypt, and Turkey in the sixteenth century, the beans from which it was brewed came from terraces in the mountains at the southern tip of the Arabian peninsula, in what is now Yemen. Consequently, when the European botanist Linnaeus began naming and categorizing the flora of the astounding new worlds his colleagues were encountering, he assigned the coffee tree the species name Coffea arabica.

Coffea arabica was the only coffee species known to world commerce for several centuries. It still provides the majority of the world’s coffees. However, it did not originate in Arabia, as Linnaeus assumed, but in the high forests of central Ethiopia, a fact not confirmed by the Western scientific community until the mid-twentieth century. Well over a hundred species of coffee now have been identified growing wild in various parts of tropical Africa, Asia, and Madagascar. Probably about thirty are cultivated, most on a very small scale. One, Coffea canephora or robusta, has come to rival Coffea arabica in importance in commerce and culture.

No one knows how Coffea arabica first came to be cultivated, when, or even where. Some historians assume that it was first cultivated in Yemen, but a strong case has been made that it was first deliberately grown in its botanical home, Ethiopia, and was carried from there to South Arabia as an already domesticated species, perhaps as early as A.D. 575.

It is not clear what sort of drink the first recorded drinkers of hot coffee actually consumed. The coffee bean is the seed of a small, thin-fleshed, sweet fruit. The first hot coffee beverage may not have been brewed from the bean at all. More likely it was made by boiling the lightly toasted husks of the coffee fruit, producing a drink still widely consumed in Yemen under the name qishr, kishr, kisher (or several other spellings), and in Europe called coffee sultan or sultana. Or perhaps both dried fruit and beans were toasted, crushed, and boiled together. The dried husks are very sweet, so any drink involving the husks would be sweet as well as caffeinated.

Considerable speculation has been focused on what finally led someone in Syria, Persia, or possibly Turkey to subject the seeds of the coffee fruit alone to a sufficiently high temperature to induce pyrolysis, thus developing the delicate flavor oils that speak to the palate so eloquently and are undoubtedly responsible for the eventual cultural victory of coffee.

These explanations range from the poetic to the plausible. Muslim legends focus on Sheik Omar, who was exiled to an infertile region of Arabia in about 1260, and according to one version of his legend discovered the benefits of roasted coffee while trying to avoid starvation by making a soup of coffee seeds. Finding them bitter, he roasted them before boiling them.

Others have claimed that farmers in Yemen or Ethiopia, while burning branches cut from coffee trees to cook their meals, discovered the value in the seeds roasted by this serendipitous process. This theory, which began turning up in coffee literature of the early twentieth century, has a storyteller’s rather than a historian’s logic.

Ian Bersten, in his provocative history Coffee Floats, Tea Sinks, supposes that someone simply discovered that the light roasting given the husks of the coffee fruit to make qishr could be turned up a notch, as it were, to produce a truly roasted coffee bean. He further suggests that the Ottoman Turks, who assumed control of southern Arabia in the mid-sixteenth century, spread the habit of drinking the new kind of roasted coffee in order to make use of a heretofore useless by-product of qishr production, the previously discarded seeds.

Certainly the Ottoman Turks were the main instigators of the spread of coffee drinking and technology, since their expanding empire facilitated cultural and commercial exchange. Bersten also speculates that Syria is the likely location of the first truly roasted coffee, since the Syrians, particularly in the city of Damascus, had developed the technology necessary to produce metal cookware, which in turn facilitated a higher roasting temperature than the earthenware bowls used by the Yemenis.

Furthermore, Bersten suggests that the odor of roasting smoke, which is produced only by pyrolysis and which many people find more enticing than the beverage itself, may have been an incentive for someone to persist in the roasting process and push it beyond the temperature that produces the fruity-smelling qishr.

All such speculations remain impossible to prove or disprove. Seeds and nuts were roasted to improve their taste and digestibility early in history, long before the development of roasted coffee, and possibly someone simply tried the same trick with coffee seeds. Or perhaps some qishr drinker toasting coffee husks and seeds wandered away from the fire too long and came back to a pleasant surprise.

At any rate, by 1550 coffee seeds or beans were definitely being roasted in the true sense of the word in Syria and Turkey, and the spectacular rise of roasted coffee to worldwide prominence in culture and commerce had begun.

Ceremonial Roasting

Early coffee roasting in Arabia was doubtless simple in the extreme. We have no detailed accounts of these earliest roasting sessions, but they probably resemble the practices still found in Arabia today, and recorded by Europeans like William Palgrave in 1863 in his Narrative of a Year’s Journey Through Central and Eastern Arabia:

Without delay Soweylim begins his preparations for coffee. These open by about five minutes of blowing with the bellows and arranging the charcoal till a sufficient heat has been produced.… He then takes a dirty knotted rag out of a niche in the wall close by, and having untied it, empties out of it three or four handfuls of unroasted coffee, the which he places on a little trencher of platted grass, and picks carefully out any blackened grains, or other non-homologous substances, commonly to be found intermixed with the berries when purchased in gross; then, after much cleansing and shaking, he pours the grain so cleansed into a large open iron ladle, and places it over the mouth of the funnel, at the same time blowing the bellows and stirring the grains gently round and round till they crackle, redden, and smoke a little, but carefully withdrawing them from the heat long before they turn black or charred, after the erroneous fashion of Turkey and Europe; after which he puts them to cool a moment on the grass platter.

Among the inhabitants of the Arabian peninsula, roasting, pulverizing, brewing, and drinking the coffee all were (and often still are) performed in one long, leisurely sitting. Both roasting and brewing were carried out over the same small fire. The roasting beans were stirred with an iron rod flattened at one end. After cooling they were dumped into a mortar, where they were pulverized to a coarse powder. The coffee was boiled, usually with some cardamom or saffron added, then strained into cups. It was drunk unsweetened.

Variants of this coffee ritual continue throughout the horn of Africa and the Middle East. Ethiopian and Eritrean immigrants to the United States have carried a version of it to their urban kitchens and living rooms.

From Brown to Black: A New Coffee Cuisine

Attentive readers of the Palgrave passage will note that the Arabians roasted their coffee to a rather light brown color. At an early point in coffee history, probably before 1600, a somewhat different approach to coffee roasting and cuisine developed in Turkey, Syria, and Egypt. The beans were brought to a very dark, almost black color, ground to a very fine powder, using either a millstone or a grinder with metal burns, and boiled and served with sugar. No spices were added to the cup, and the coffee was not strained but delivered with some of the powdery grounds still floating in the coffee, suspended in the sweet liquid. It was served in small cups rather than the somewhat larger cups preferred by the Arabians.

The reasons for this change in style of roast, brewing, and serving are not known, but doubtless the very dark roast facilitated grinding the coffee to a fine powder. Lighter-roasted beans are tougher in texture and more difficult to pulverize than the more brittle darker roasts. And sugar, a native of India, which had been put into large-scale cultivation relatively recently in the Middle East, helped offset the bitterness of the dark roast and accentuate its sweet undertones. Thus a new technology (the hand grinder with metal burrs); a new, dark roasting style; and the availability of sugar all coincided to contribute to the development of the coffee cuisine we now call Turkish.

Why Turkish? Why not Egyptian, for example, or Syrian? Because this cuisine penetrated Europe via contacts with the Ottoman Turks, first through Venice into northern Italy and later through the Balkans and Vienna into Central Europe. Early European coffee drinkers all roasted their coffee very dark and drank it in the “Turkish” fashion, boiled with sugar.

Coffee Goes Global

During the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries the habit of coffee drinking spread westward across Europe and eastward into India and what is now Indonesia. As a cultivated plant it burst out of Yemen: First a Muslim pilgrim carried it to India, then Europeans took it to Ceylon and Java. From Java they carried it to indoor botanical gardens in Amsterdam and Paris, then as a lucrative new crop to the Caribbean and South America. In a few short decades millions of trees were providing revenue for plantation owners and merchants, and mental fuel for a new generation of philosophers and thinkers gathering in the coffeehouses of London, Paris, and Vienna.

Throughout coffee’s spread as one of the new commodity crops that fed the growing global trade network of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, it was associated with sugar. Coffee and sugar went hand in hand, both as sister tropical cash crops and as partners in the coffeehouses and coffee cups of the world. Coffee was undoubtedly a less destructive crop than sugar, both to the environment and to workers. It is a small tree typically grown under the shade of larger trees rather than in vast fields, and, unlike sugar, often provided a small cash crop for independent peasant farmers.

Nevertheless, in a global irony, coffee simultaneously became a symbol of both oppression and liberation. It developed as an instrument of social and economic exploitation in the tropics, as a plantation elite grew wealthy on the labor of darker-skinned workers, yet simultaneously fueled the intellectual revolution of the European Enlightenment and political revolutions in France and the United States. Coffee and coffeehouses were intimately associated with virtually all of the great cultural and political upheavals of the time.

It was also during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries that Europeans introduced coffee to its second great companion: milk. The ancestor of America’s latest favorite, the hot-milk-and-espresso caffè latte, was born in Vienna after the Turkish siege of 1683, when Franz Kolschitzky started Vienna’s first coffeehouse with coffee left behind by the retreating Turks. Kolschitzky found that in order to woo the Viennese away from their breakfasts of warm beer he had to abandon the Turkish style of coffee brewing, strain the new drink, and serve it with milk.

From Vienna the practice of straining coffee, rather than serving it Turkish style as a suspension, spread westward through Europe, and with it the custom of serving coffee with hot milk. To this day the line between those European societies that strain their coffee and drink it with milk and those that drink their coffee Turkish style in a sweet suspension roughly corresponds to the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century border between the Ottoman Empire and Christian Europe. Austrians and Italians, for example, drink their coffee strained and with milk, whereas most coffee drinkers in the Balkans, which remained under the control of the Ottomans until well into the nineteenth century, take their coffee Turkish style.

Roasting in a Technological Rut

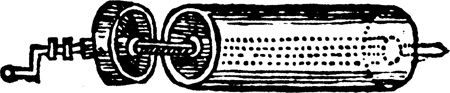

Despite these dramatic developments in coffee drinking and growing during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, roasting technology itself changed very little. The most common approach was a simple carryover from Middle Eastern practice: Beans were put in an iron pan over a fire and stirred until they were brown. Somewhat more sophisticated devices tumbled the beans inside metal cylinders or globes that were suspended over a fire and turned by hand. Some of these apparatuses could roast several pounds of coffee at a time and were used in coffeehouses and small retail shops; others roasted a pound or less over the embers of home fireplaces. See the illustration below and here for a sampling of these early roasting devices.

One of the earliest (c 1650) representations of a small cylindrical coffee roaster, ancestor of the devices that still roast much of the coffee we drink today. It was turned over the hot coals of a brazier or fireplace.

More Unanswerable Questions

Where did Europeans and Americans in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries roast their coffee? Did they roast it at home or buy it in shops? How dark did they roast it? How might it have tasted when compared to our contemporary roasts?

Only the first two of these questions can be answered with any certainty. Coffee was roasted either in the home, often by servants, or in small shops or stalls and sold in bulk like any other produce. There is no evidence that roasting coffee was considered any more difficult or challenging than other kitchen chores. In fact, it appears that, in Europe at least, it was a job often given over to older children.

How well roasted was this coffee? What did it taste like? Iron pans, irregular heat, and children doing the roasting probably meant a technically poor roast: inconsistent and occasionally scorched. The storekeepers probably did better, though not by much.

But again, the coffee was definitely fresh. A case certainly could be made that kitchen-roasted coffee in these centuries tasted considerably better than today’s instants and cheaper canned coffees.

Roast Style and Geography

Taste in darkness of roast doubtless differed from place to place according to cultural preference, much as it does today. In most of Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries coffee continued to be roasted in dark, Turkish style. A pamphlet from seventeenth-century England, for example, advises coffee lovers to “take what quantity [of coffee beans] you please and over a charcoal fire, in an old pudding pan or frying pan, keep them always stirring til they be quite black.”

At some point, however, tastes in northern Europe—Germany, Scandinavia, and England—modulated to a roast lighter than that of the rest of Europe, which retained a preference for the somewhat darker roasts deriving from the Turkish tradition. This distinction carried over to the New World: North Americans largely adopted the lighter roasts of the dominant northern European colonists and Latin Americans the darker roasts of their southern European colonizers.

I have yet to come across a plausible explanation as to why northern Europe abandoned the darker roasts of the earlier Turkish-influenced tradition for the later lighter roasts. This shift in roast preference apparently occurred in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, and it probably was related in some way to the development of the taste for filtered coffee that took place during the same period. Some have connected it to the taste for lighter beverages like tea and beer in northern Europe, which (the theory goes) influenced tastes in coffee roasting and brewing.

Arabia and parts of the horn of Africa retained their original taste for a lighter-roast coffee, drunk with spices but without sugar.

Enter the Industrial Revolution

At the beginning of the nineteenth century most western Europeans and Americans lived in the countryside and made their living through agriculture; by the end of the century most resided in cities and earned their livelihood in industry and services. At the beginning of the century most spent their lives isolated inside an envelope of tradition; by 1900 many were literate and participated in a wider world in which newspapers and advertising profoundly influenced the details of their lives. At the beginning of the century machinery and tools were simple, and most power derived from renewable resources like water and wind; by the end complex machinery touched every facet of people’s lives, and power overwhelmingly was provided by coal and oil.

Like everything else, coffee was swept along in these changes. As the nineteenth century began, coffee beans were toasted in small, simple machines, either at home or in shops and coffeehouses. By the end of the century the new urban middle class was increasingly buying coffee roasted in large, sophisticated machines and sold in packages by brand name.

Naturally this last development was uneven. Among industrialized nations the United States led in replacing home roasting with packaged preroasted and preground coffee. Germany and Great Britain were close behind, with France, Italy, and industrializing nations elsewhere hanging on to older, small-scale roasting traditions.

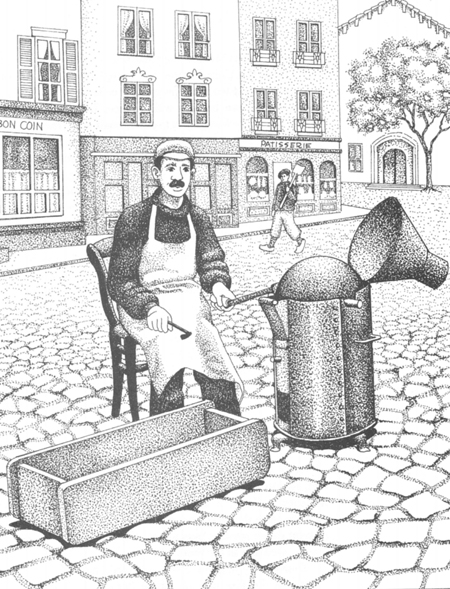

An example of one of the earliest advertisements intended to woo people away from home roasting to packaged, brand-name coffees is reproduced here. This sort of advertising appeared at a time when increasing numbers of Americans and Europeans found themselves traveling farther and farther to their places of employment. In working-class families women as well as men worked away from home, and toward the end of the century somewhat better-off families, who once employed live-in servants to take care of tasks like coffee roasting, were forced to do it themselves. In this context it is easy to see why people might begin to prefer the costlier but more convenient option of preroasted coffee.

New preferences for store-bought bread and preroasted coffee also were driven by the myth of progress that infatuated the industrialized world throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Packaged preroasted coffee was modern, clean, fashionable, and with-it. Roasting your own coffee was dirty, clumsy, grubby, and old-fashioned, something only your ignorant country cousins did.

The Pursuit of Consistency

With advertising and brand names came the need for a consistent, recognizable product. When a consumer bought your coffee in its fancy package, it was important to make the coffee inside the package taste the same way now as it did last week. The new commercial coffee roasters pursued consistency in both the green coffee they roasted and in the roast itself.

Consistency in green coffee was facilitated in several ways. The international coffee trade became better organized and more sophisticated in the language and categories it used to describe coffees and carry on its business. Countries where coffee was grown introduced complex standards for grading beans. The art of blending developed: Professionals learned how to juggle coffees from different crops and regions in order to maintain a consistent taste while controlling costs.

Meanwhile the American coffee industry developed a trade language for degree or style of roast: cinnamon, light, medium, high, city, full city, dark, heavy. Firms settled on a roast style and rigorously attempted to maintain it.

Tireless Tinkering: Nineteenth-Century Roasting Technology

It is never clear whether changes in technology drive changes in society or vice versa, but certainly the two went hand in hand in transforming nineteenth-century coffee roasting from a small-scale, personal act to a large-scale, industrial procedure fed by advertising and mass-marketing techniques. The consistency in roast style demanded by brand-name marketing could only be obtained through a more refined roasting technology.

The restless innovation of the Industrial Revolution, the tireless entrepreneurial tinkering aimed at coming up with yet another machine, still one more moneymaking technical wrinkle, claimed all aspects of coffee during the nineteenth century, from roasting through brewing. Proposals for new—or almost new—coffeemakers, coffee grinders, and coffee roasters streamed through the doors of patent offices in industrializing countries. Although only a few of the many patents had significant impact, enough did to totally transform roasting technology over the course of the century.

Coffee continued to be roasted in hollow cylinders or globes, but the cylinders and globes dramatically increased in size as coffee roasting moved from kitchens and small storefront shops to large roasting factories. See here for a look at the interior of an American coffee-roasting plant from the mid-nineteenth century.

The roasting drums were now turned by machine, first by steam, then near the end of the century by electricity. Similarly, roasting heat was first provided by coal or wood, then by natural gas. By the end of the century a lively debate developed between adherents of “direct” gas roasting, which meant that the flame and the hot gases were literally present inside the roasting chamber, and “indirect” gas roasting, which meant that heat was applied only to the outside of the roasting chamber and sucked through the chamber by means of a fan or air pump.

Further technical innovations focused on two problems: (1) controlling the timing or duration of the roast with precision, and (2) achieving an even roast from bean to bean and around the circumference of each individual bean.

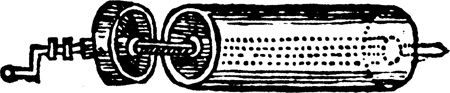

Based on a turn-of-the-century photograph, this drawing depicts one of the many itinerant coffee roasters who with their simple equipment roamed the cities and towns of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century France, setting up in the street and roasting coffee for neighborhood households. With his left hand he is turning the ball-shaped roasting chamber above a charcoal fire; in his right he holds a metal hook used to open the door in the roasting ball to check the color of the beans. The boxlike wooden object at his feet is his cooling tray. When he judged the coffee properly roasted, he flipped the ball on its hinged frame up and out of the top of the stove and over the cooling tray, into which it deposited its charge of hot beans.

First the timing issue. As the drums and globes of commercial roasting machines grew larger it became more and more difficult to cool the large masses of roasting coffee with any precision because the beans continued to roast from their own internal heat long after being dumped from the machine or removed from the heat source.

Solutions in the early part of the century tended to focus on ways of dumping the beans quickly and easily. With the Carter Pull-Out machines pictured in the engraving here, for example, the selling point was exactly that: The roasting drum could be pulled out of the oven and easily emptied. However, as can be seen in the illustration, the beans still had to be stirred manually to hasten cooling.

Starting in 1867 fans or air pumps were introduced to automate the cooling. The beans were dumped into large pans or trays. While machine-driven paddles stirred the beans, fans pulled cool air through them, both reducing their surface temperature and carrying away the smoke produced by the freshly roasted beans.

The second technical problem addressed by late-nineteenth-century innovation was the question of even roasting. At the beginning of the century most roasting drums and globes were simple hollow chambers. The beans tended to collect in a relatively stable mass at the bottom of the turning drum or globe. Consequently some beans remained at the bottom of the pile in close contact with the hot metal of the drum and tended to scorch or roast darker than those at the top of the shifting mass. Furthermore the coating of oil produced by the roast often caused beans to stick to the hot metal walls of the roasting chamber.

Starting in the nineteenth century, vanes or blades that tossed the coffee as the drum or globe turned were added to the inside of the roasting chamber, facilitating a more even roast. And in 1864 Jabez Burns, an American roasting-technology innovator, further resolved the problem of dumping the beans by developing a double-screw arrangement of vanes inside the roasting drum that worked the beans up and down the length of the cylinder as it turned. The operator then had only to open the door of the roasting cylinder and the beans, rather than heading back away from the door for another trip up the cylinder, simply tumbled out into the cooling tray.

But the most effective answer to uneven roasting came toward the end of the century. To supplement the usual heat applied to the outside of the drum, hot air was drawn through the drum by a fan or air pump, often the same fan or pump used to suck air through the beans to cool them. The combination of moving air and vanes tossing the coffee meant the coffee was roasted more by contact with hot air than by contact with hot metal, improving both the consistency and the speed of the roast. Furthermore, efforts were made to deliver heat evenly around the entire circumference of the drum rather than only at the bottom, usually by enclosing the drum inside a second metal wall and circulating the heat between this wall and the outside of the drum.

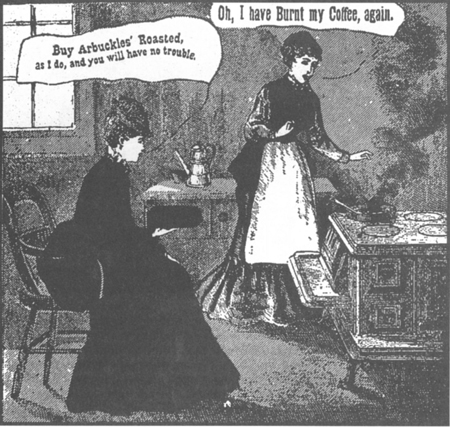

This nineteenth-century illustration suggests the outpouring of invention that was lavished on the simple act of coffee brewing during the early Industrial Revolution. Similar ingenuity was bestowed on coffee roasting. Scores of almost identical home-roasting devices were patented, as well as numerous variations on shop and factory machines.

The sum total of these innovations—gas heat directed evenly around the drum, a means of rapidly and precisely dumping the beans, vanes inside the drum, and air pumps to suck hot air through the roasting chamber and room-temperature air through the cooling beans—produced the basic configuration of the classic drum roaster. It is a configuration that endures today as the fundamental form of most smaller-scale roasting equipment. See here for an illustrated description of a representative drum roaster.

Of course there were (and are) many variations of this essential technology. Some turn-of-the-century machines put the gas flame inside the drum, for example. Most larger systems today spray the hot beans with a short burst of water to decisively kick off the cooling process, an approach called water quenching, as opposed to the pure air quenching described earlier.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, coating the hot beans with sugar to help preserve them was a popular practice. Today sugar glazing of coffee beans is practiced only in some regions of Latin America and Europe.

The interior of an American roasting plant in the mid-nineteenth century. Heat was provided by coal; brick ovens entirely surrounded the roasting drums, distributing heat more evenly around the drums than did earlier designs that heated the drums from the bottom only. The drums were perforated to vent the roasting smoke. These Carter Pull-Out roasters were turned by belts connecting to steam power, but were “pulled out” of the ovens by hand. The beans were dumped into wooden trays, where they were cooled by stirring with shovels.

Throughout these decades of change some roasters stuck stubbornly to earlier technologies, as they still do today. Roasters in places as diverse as Japan, Brazil, and the United States continue to use wood or charcoal to roast their coffee, for example. They or their clients value the slow roast and the smoky nuance imparted to the beans by the process.

Nevertheless, the indirectly heated drum roaster using a convection system drawing hot air through the turning drum remains the norm today for all but the largest roasting apparatus.

An advertisement aimed at getting Americans of the 1870s to give up home roasting for packaged coffees. Arbuckles Brothers pioneered preroasted, brand-name coffee. Note the contrast between the up-to-date woman on the left, fashionably dressed and holding a package of preroasted coffee, and her distracted old-fashioned friend, tied to her stove and messing up the kitchen with coffee smoke.

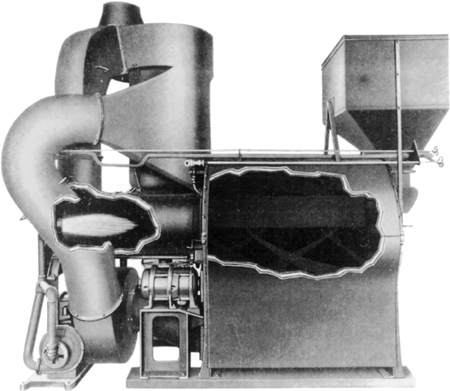

The Jabez Burns Thermalo roaster of 1934. Previous machines supplemented the heat applied to the outside of the roasting drum with relatively gentle currents of hot air drawn through the drum. The Burns machine dispensed with the heat outside the drum, instead relying on a high-velocity blast of hot air roaring through the drum, thus roasting the coffee more by contact with hot air than by contact with hot metal. Burns machines like this one are still used in many American roasting establishments. The principle pioneered by the Thermalo reached its ultimate development in today’s fluid-bed machines, which lift as well as roast the beans in the same rapidly moving, vertical column of hot air.

Twentieth-Century Innovations: Hot Air Only

Obviously the twentieth century could not leave coffee-roasting technology alone. The goal of roasting coffee beans as they fly through the air rather than rattling off hot metal or sizzling in a gas flame received two additional boosts in the middle years of the century.

In 1934 the Jabez Burns company developed a machine (the first model was called the Thermalo; see illustration above) that applied no heat whatsoever to the drum itself, instead relying entirely on a powerful stream of hot air howling through the drum. This arrangement permitted the use of a lower air temperature during roasting, since the rapidly moving air stripped the beans of their envelope of roasting gas and made the actual heat transfer from air to bean more efficient. Adherents of the new system argued that lower roasting temperatures and relatively rapid roasting burn off fewer flavor oils and produce a more aromatic coffee.

Also in the 1930s the first roasting device appeared that quite logically dispensed with the roasting drum altogether and instead used the same powerful column of hot air that roasted the beans to also agitate them. Such fluid- (or fluidized-) bed roasters work essentially like today’s household hot-air corn poppers: The stream of hot air simultaneously tumbles and roasts the beans. The bed of beans seethes like fluid, hence the name. Fluid-bed roasters offer the same technical advantages as the Burns Thermalo machine: The rapidly moving air permits a lower roast temperature and a faster roast, theoretically driving off fewer flavor oils.

In the United States today the most widely used fluid-bed designs are the work of Michael Sivetz, an influential American coffee technician and writer. In the most popular Sivetz design the beans are forced upward along a vertical wall by the stream of hot air, then cascade back down again in a continuous rotation. See here for an illustrated description of one style of Sivetz roaster.

Several other fluid-bed designs have been manufactured over the past fifty years, and more continue to enter the market. Some are simple variations on the original patents from fifty years ago, in which hot air rising from the bottom of a funnel-shaped roasting chamber creates a sort of fountain of beans that seethes upward in the middle before tumbling back down the sides of the chamber. Other designs, like Australian Ian Bersten’s Roller Roaster and the Burns System 90 centrifugal, packed-bed roaster, are efforts to genuinely rethink the original fluid-bed principle. Still others are display roasters, which emphasize the drama of the procedure by enclosing the seething beans in glass. The idea is to draw customers into the store by flaunting roasting’s technological and gourmet intrigue. All of the newer small fluid-bed shop roasters attempt to simplify and automate the roasting process as much as possible.

Electrified Roasting

Electricity came into use late in the nineteenth century to turn drums and pump air through conventional roasters. Electricity has not achieved great success as a heat source for large-scale roasting, however. As any cook knows, electric heat responds sluggishly to command compared to gas. Gas also is usually cheaper. For these reasons it has remained the preferred heat source in most larger shop and factory roasting installations.

Nevertheless, several shop roasting devices manufactured in the early part of the century provided roasting heat with electrical elements, and electricity continues in use in many small-scale roasting installations today.

Infrared and Microwaves

The use of electromagnetic waves or radiation to roast coffee has had mixed success.

Infrared is radiation with a wavelength greater than visible light but shorter than microwaves. It is used in outdoor-café heaters, portable home heaters, and similar applications.

The first infrared roasting machines appeared in the 1950s. Today one of the leading small American shop roasters, the Diedrich roaster, uses infrared heat. Like most drum roasters, the Diedrich machine combines heat applied to the outside of the roasting drum with currents of hot air drawn through it to roast the coffee. Unlike conventional drum roasters, however, the heat is supplied by radiating, gas-heated ceramic tiles. Metal heat exchangers apply some of the radiant heat to warm the air pulled through the drum. Proponents of the Diedrich machine admire its relative energy efficiency, low emissions, and clean-tasting roast.

Figuring out how to use microwaves to roast coffee has proven to be a tricky challenge, but sure enough, someone has figured out how to do it. The world’s first genuine microwave coffee-roasting system, tentatively called Wave Roast, may appear about the time this book does. It is a small-scale roasting technology designed to make use of America’s ubiquitous microwave ovens. See here.

Roasting Without End: The Continuous Roaster

For large roasting companies time is money, and emptying beans from the roaster and reloading with more beans takes time. Such economic motives lay behind still another twentieth-century development, the continuous roaster, in which the roasting process never stops until the machine is turned off.

The most common continuous-roasting design elongates the typical roasting drum and puts a sort of screw arrangement inside it. As the drum turns, the screwlike vanes transport the coffee from one end of the drum to the other in a slow, one-way trip. Hot air is circulated across the drum at the front end and cool air at the far end. The movement of the beans through the drum is timed so that green coffee entering the drum is first roasted then cooled by the time it tumbles out at the end of its journey. Variations of this principle continue to be employed in machines used today in many large commercial roasting establishments. See here for an illustrated description.

The fluid-bed principle has been pressed into service for continuous roasters as well. In these designs hot air simultaneously roasts and stirs large batches of coffee beans, which drop into a cooling chamber as soon as they are roasted, to be followed immediately by another batch of green coffee and still another, in continuous succession.

Conventional roasting machines that need to be stopped completely to be emptied and reloaded are now called batch roasters to distinguish them from continuous designs. Most specialty or fancy coffee-roasting establishments have stayed with batch roasters. If you are roasting a Kenyan coffee in the morning, a Sumatra at midday, and an espresso blend in the afternoon, the single-minded persistence of the continuous design makes no sense. On the other hand, large commercial roasting companies that roast a similar blend of coffee the same way every day find the consistent conveyor-belt approach embodied in such machines practical and desirable.

Chaff and Roasting Smoke

Some developments in nineteenth- and twentieth-century coffee-roasting technology have little to do with improving taste or the bottom line but instead respond to safety and environmental concerns.

The earliest of these issues to be faced involved roasting chaff. Green coffee arrives at the roaster with small, dry flakes of the innermost skin, or silver skin, still clinging to the bean. During roasting most of these flakes separate from the beans and float wherever air currents take them. They can be dangerous if they settle in one place and ignite, and are always annoying.

Recall that in the late nineteenth century fans were put into service to pull hot air through the roasting drum. This advance led to the development of the cyclone, a large, hollow, cone-shaped object that typically sits behind the roasting chamber. After the hot air is pulled from the roasting drum it is allowed to circulate inside the cyclone, where most of the chaff it has been carrying settles out. The chaff-free air and smoke then continue up and out of the chimney while the chaff collects at the base of the cyclone, where it can be removed and disposed of.

In the twentieth century the persistent odor of the roasting smoke and its potential pollutants became an issue. Technology came to the rescue with afterburners and catalytic devices that remove a good deal of the roasting by-products from the existing gases. Fuel was often conserved by recirculating at least a portion of the hot roasting air back through the roasting chamber.

A Revolution in Measurement and Control

At the arrival of the twenty-first century, there are signs that roasting technology may be undergoing still another revolution. Barring some breakthrough in the use of microwaves, it seems unlikely that the basic technologies for applying heat to the beans and keeping them moving will change. What is changing is the way the roast is monitored and controlled.

Traditionalists: Nose and Eye

Until recently small-scale roasting remained not too far removed from the hands-on approach of the Neapolitans cranking their abbrustulaturo on their balconies as recalled by Eduardo De Filippo in Chapter I.

Traditional roasters rely on a combination of eye (color of the beans), ear (sound of the crackling sounds emitted by the beans) and nose (the changing volume and scent of the roasting smoke). They take samples of the roasting beans by means of a little instrument called a trier, which they insert through a hole in the front of the roasting machine to collect a sample of the tumbling beans. The decision when to stop the roast is based on the color of the beans read in light of experience. Adjustments to the temperature inside the roast chamber also may be made on the basis of experience, both with roasting generally and with the idiosyncrasies of specific coffees.

For a traditionalist, roasting is an art in the old sense of the word: a hands-on experience unfolding again and again in the arena of memory and the senses.

Science Sneaks Up on Art

What was once a matter of art and the human senses, however, is increasingly becoming a matter of science and instrumentation in which individual memory is replaced by an externalized, collective memory of numbers and graphs.

Several instruments and controls are making this change possible. The first is a simple device that measures the approximate internal temperature of the roasting beans. Usually called a thermocouple or heat probe, it is an electronic thermometer whose sensing end is placed inside the roasting chamber so that it is entirely surrounded by the moving mass of beans. Although the air temperature inside the roasting chamber is different from the temperature of the beans, the beans tend to insulate the sensor from the air and transmit an approximate reading of their inner, collective heat to a display on the outside of the machine.

Once the chemical changes associated with roasting set in, the internal heat of the beans becomes a reasonably precise indicator of how far along the roast is. Think of the little thermometers that pop out of roasted turkeys when they’re properly done. The inner temperature of roasting beans is a similar indicator of “doneness,” or degree of roast. Thus the electronic thermometer can be used in place of the eye to gauge when to conclude the roast or make adjustments to the temperature inside the roast chamber. A chart matching approximate internal temperature with degree or style of roast appears here. With some contemporary roasting machinery it is possible to set the instrumentation to trigger the cooling cycle automatically when the beans have reached a predetermined internal temperature.

A second important control links the temperature inside the roasting chamber with the heat supply, automatically modifying the amount of heat to maintain a steady, predetermined temperature inside the chamber. This linkage is desirable because once the beans reach pyrolysis they emit their own heat, raising the temperature in the roasting chamber. If the amount of heat applied from outside the chamber remains uniform, as it does with the simpler conventional apparatus, then the heat inside the chamber begins to accelerate near the end of the roast, fed by the new heat supplied by the chemical changes in the beans. According to some roast philosophies, these spiraling, uncontrolled temperatures may roast the beans too quickly, burning off aromatics and weakening the structure of the bean.

A third instrument is the near-infrared spectrophotometer. This device, often called an Agtron after its manufacturers and developer, measures certain wavelengths of “color” or electromagnetic energy that are not visible to the human eye but that correlate particularly well with the degree of roast. Furthermore, the Agtron is not deceived by the changing quality of ambient light or by other sources of human fallibility like bad moods on talkative coworkers. The near-infrared spectrophotometer not only measures its narrow, telltale band of energy with consistency and precision, but translates it into a number as well. Thus two people thousands of miles apart can compare the development of their roasts by exchanging the readings on their instruments.

It has long been known that denser and/or moister coffees are slower to reach a given roast style than lighter or drier beans. Today’s technically inclined roaster takes precise measurements of bean density and sets roast-chamber temperature and other variables to compensate for these differences according to a quantified system. The traditional roaster can only approximate such adjustments, basing them on past experience with the behavior of a given coffee in the roaster.

Finally, the velocity of the convection currents of air and gases moving through the roasting chamber can be controlled with great precision in some contemporary roasting equipment. Traditional roasters have always been able to control air currents in their drum roasters by adjusting a damper, much as we control convection currents in our home fireplaces and wood stoves. But again, this control was approximate rather than quantifiable and precise.

Thus today’s systematic roaster has four to five quantifiable variables with which to work: original moisture content and density of the beans, temperature in the roasting chamber, internal temperature of the roasting beans, precisely measured color of the roasting beans, and (with some equipment) air velocity in the roasting chamber. Add in careful compensation for environmental factors like ambient temperature, altitude, and barometric pressure, and figures provided by these four or five variables can describe the progress and conclusion of a given roasting session for a given coffee, replacing the ear, nose, eye, and memory with a set of hard data. With the use of computers, complex settings can be established to vary the temperature and other conditions inside the roast chamber on an almost second-by-second basis, permitting subtle modifications of the final taste of the roast, an approach called profile roasting by its proponents. Older, blander coffees can be made to taste somewhat more complex, for example, and rough or acidy coffees can be tamed and made smoother and sweeter.

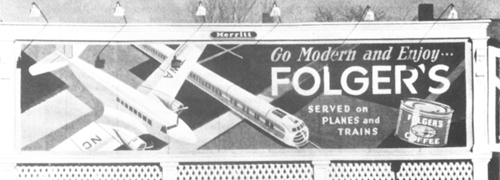

This billboard from the 1930s dramatizes how preroasted, preground coffee was associated with modernity and progress in the early twentieth century.

But It Still Needs to Be Tasted

You may have patiently followed all of the preceding, or simply skimmed it to get to the punch line. Either way you can see how the use of instrumentation permits the translation of what was once an intuitive system held in the memory and nervous system of the roaster to a complex but precise series of numbers.

One human sense that hopefully will never become obsolete is taste. For even if the day arrives when roasting is performed entirely on the basis of system and number, the roaster (or roastmaster as he/she is increasingly called in these upscale days) still will need to taste the coffee when it comes out of the roasting apparatus and make some informed adjustments to those numbers based on personal preference and roasting philosophy. Thus the variety of taste achieved by different approaches to roasting may continue to surprise our palates and enrich the culture and connoisseurship of coffee. Roasting, perhaps, will remain art as well as science.

Social History: Quality Makes a Comeback

To conclude, let’s return to the social history of roasting and bring it to its rather surprising conclusion in the twentieth century.

Although preroasted, preground coffee sold under brand names claimed more and more of the market in industrialized Europe and America during the first half of the twentieth century, older customs hung on. In southern Europe many people continued to roast their coffee at home well into the 1960s, and even in the United States small storefront roasting shops survived in urban neighborhoods.

As the century wore on, however, the trend toward convenience and standardization accelerated. By the 1960s packaged coffee identified by brand name dominated the urbanized world. Coffee was sold not only preroasted and preground, but in the case of soluble coffees, prebrewed. I recall visiting two of the world’s most famous coffee-growing regions in the 1970s and finding only instant coffee served in restaurants and cafés. Most Americans and Europeans, who were now called consumers, had forgotten that coffee could be roasted at home, or even that it could be ground at home. Coffee doubtless appeared in their consciousness, perhaps even in their dreams, as round cans or bottles with familiar logos on the sides.

The simple process of home roasting became a lost art, pursued in industrialized societies only by a handful of cranky individualists and elsewhere by isolated rural people who roasted their own coffee as much from economic necessity as from habit or tradition.

Canned coffee became a favorite product to offer at great savings to lure people into large stores. The tendency to use coffee as an advertized loss leading sale item helped make it one of the most cost-sensitive food products of the 1950s and ’60s, and understandably undercut the quality of the coffee inside those colorful cans. Commercial canned blends that were reasonably flavorful at the close of World War II became flat and lifeless by the end of the 1960s.

At that point, as mentioned in Chapter 1, a new phase of the coffee story began, a countermovement to the march toward uniformity and convenience at the cost of quality and variety. The few small shops that still roasted their own coffee and sold it in bulk provided a foundation for a revival of quality coffees that has gone far to transform coffee-consuming habits in the United States and many other parts of the industrialized world.

This revival is usually called the specialty-coffee movement. Thus the end of the twentieth century is witnessing a return to the coffee-roasting and -selling practices that dominated at its beginning, with people buying their coffee in bulk and grinding it themselves before brewing. Perhaps the United States, which has led the world down the superhighway of convenience, may be pointing it back along the slower road toward quality and authenticity.

From Gourmet Ghetto to Shopping Mall

However, a countertrend toward a new kind of standardization seems to be gaining momentum. The specialty-coffee movement began in the 1960s with small roasters selling their coffee as fresh as possible to neighborhood customers. However, specialty coffee has now moved out of gourmet ghettos and into suburban shopping malls. As it has, the stakes have risen. Neighborhood roasters have become regional chains, and regional chains have sold stock and gone national or international.

Today your neighborhood specialty-coffee store may well be one of a chain of fifty or, in the extraordinary case of Starbucks, one of thousands. Starbucks buys good-quality coffee, but roasts it in large plants and distributes it to a vast network of virtually identical retail outlets around the world.

Quirky and Individualistic

Starbucks is in many ways a happy marriage between the quality-conscious idealism of the specialty-coffee movement and rigorous corporate power and discipline. Nevertheless it does not entirely represent the world of coffee as I would like to see it enter the twenty-first century: quirky and individualistic, with local roasters selling their own styles of coffee in their own neighborhoods, a world full of choice and surprises.

For those who really love coffee, the moment may have come to leave both cans and enormous coffee-store chains behind, and enjoy coffee as people did before the advent of brand names, chain stores, and advertising: by roasting their own.