This extract of a newspaper article from 1953 portrays, in the example of Ali, the situation of Iranian merchants in Hamburg from a local German viewpoint. The quotation underlines the transnational dimension of Ali’s business activities. It presents the local insertion of merchants as deriving from their important place in the local economy over several decades. Thereby, the article states that Iranian merchant families maintain Iranian values in private, but conform to local ways of life in public. Further, it alludes to the role of family relations in their local engagements, and implicitly poses the question of the possibilities for a greater integration of their German-grown children. This chapter concentrates on diversity within kin groups. Utilizing a diachronic approach, I investigate how Ali and Jalal, two merchants with Azeri and Gilaki ethnic identifications who came to Hamburg in the 1930s, mobilized kinship relations to generate capital. Which role do constructions of gender, generational, and age hierarchies play in differentiation within these transnational families? How do these dynamics influence the descendants’ own identifications and their usage in strategies of capital creation, in particular, the way they position themselves in Iranian social fields? At the same time, this ethnographic analysis that interweaves different sources of material, oral history accounts of living family members and contemporaries, secondary literature, and family and public archives also aims at historicizing Iranian immigration to Hamburg.[Ali] is a merchant, an importer, whose company is located in Tehran, and in Tabriz, and at the Ballinndamm in Hamburg . He plays an important role in Hamburg’s big Persian colony . Since decades, the Persians are well-reputed merchants in our Hanseatic city. Those who settled in Hamburg and their families brought to us a little bit of Orient. In their well-kept homes near the Alster, they cultivate native custom and manner, even if their children grew on the shores of Elbe and Alster and they only went to school with Jungs and Deerns [local dialect: boys and girls] from Hamburg. (Hamburger Anzeiger, 17/08/1953,1 author’s translation, emphasis in the original)

In anthropology, family relations are conceived of not as naturally given, but as socially constructed. Kinship is a state of doing rather than a state of being (Schneider 1984). Defined through its relationality, it relies on a “mutuality of being”, that is, on collective experience of emotions and life events (Sahlins 2013). Following Pierre Bourdieu (1990, 167), kinship is also a set of possible relations one may draw upon for their strategic and practical use through the engagement in “constant maintenance work” in the form of “material and symbolic exchanges”. I thus understand kinship through the description of the struggle about the definition of roles within a system of relationships, moving between changing degrees of differentiation and connection (Strathern 2014).

Studies of transnational families show that kinship relations may generate crucial resources: the creation and circulation of economic capital is certainly one of the most studied aspects of transnational kinship relations (Conway and Cohen 1998; Monsutti 2005; Sana and Massey 2005). Moreover, these ties represent a social resource which migrants may build on, for example, when emigrating (Massey et al. 1998, 42ff.; Moghaddari 2015, 134f.), or rely on for child care when being away (Baldassar and Merla 2014). In her study of Chinese transnational business families, Aihwa Ong (1999) made an important contribution to the study of the way kinship, that is, relations of alliance and filiation, is involved in practices of flexible capital creation through migration. Ong demonstrates how family fathers strategically place their kin in different countries to engage in professional trajectories, higher education, citizenship acquisition, and marriage alliances, in order to increase the family’s collective efficiency in generating capital in different social fields (1999, 124–57). This chapter expands on her work as it interrogates, through the relational approach to kinship, the family members’ responses to hierarchical role attribution. Moreover, based on a historically informed ethnography and research on kinship relations in other transnational trade networks (Curtin 1984; Fewkes 2009), it stresses the dimension of time and temporality in the understanding of geographical flexibility.as families that live some or most of the time separated from each other, yet hold together and create something that can be seen as a feeling of collective welfare and unity, namely ‘familyhood’, even across national borders. (Bryceson and Vuorela 2002, 3)

A brief sketch of the socio-economic organization of merchants in Iran and in Germany sets the grounds for the ethnographic description of Iranian merchants’ flexible strategies of capital creation through marriages, transnational brotherly relations, and the image of the nuclear family. Building on these descriptions, the analysis of differentiations and disruptions that developed between kin offers an understanding of how the experience of kinship, in combination with inherited resources (or their lack), influences the ways in which migrants’ descendants engage with other people of Iranian origin.

Bazaris Meet Kaufmänner: Conditions of Early Iranian Mercantile Migration

As mentioned in the introduction, Iranian migration to Hamburg began—although initially very slowly—after the conclusion of the first “commercial and friendship treaty” between Iran and the Hanseatic cities of Bremen, Lübeck, and Hamburg2 in 1857 (Khan, Rumpf 23/07/18573). Of course, commercial cooperation between Europe and Iran was not completely new: economic relations can be traced back to historical trade networks of the silk route which connected Europe to Asia, passing through Iran (Tsutomu 2013, 235).4 Local products, such as carpets, dried fruits, silk worms, cocoons, and opium were exported to Russia, to the Caucasus, and, via Turkey, to Europe. According to the 80-year-old merchant Akbar, Istanbul was one of the first foreign destinations of successful Iranian merchants.5 However, with the rising efficiency of trade6 and with growing competition (Tsutomu 2013, 247), they searched for alternative business strategies. The establishment of bilateral trade relations with German cities thus offered the possibility to set up a branch in Hamburg and reach new markets in Europe and North America.

As in many similar historical cases, these trade networks were mainly based on kinship relations. Fewkes (2009, 61ff.) and Van (2011), for example, describe the centrality of filiation and alliance in sustaining reliability and creating resources acknowledged in different locations of trade within historical trade networks in Ladakh and New England, respectively. Indeed, setting up a new branch in Hamburg was frequently a son’s task. Importantly, this migration was predominantly male, as most of these rather young men were either bachelors or they left their wives and children in Iran. This group of pioneering merchants was marked by strong ethnic, linguistic, and religious diversity,7 but held together by a shared adherence to the logics of Iranians bazari networks.

In Iran, the bazaris, just like urban entrepreneurs and the clergy, can be defined as the traditional “propertied middle class” (Abrahamian 1982, 432f.). At the time the first merchants came to Hamburg, the Iranian bazar’s social structure was characterized by a high level of social, cultural, ethnic, and religious diversity. According to Arang Keshvarzian, there was no official monitoring organism that supervised commercial activities. Instead, based on a tight social network of mutual acquaintance, informal socio-economic activities8 relied on a system of reputation in which traders could monitor each other’s activities, reward honesty, and sanction betrayal through public shaming. Multiplex relations, including kinship, friendship, neighborhood relations, and common religious and leisure practices, cutting across professional hierarchies sustain the mutual monitoring. Shared values such as honesty, generosity, religious adherence, modesty, and expertise were the basis for collective identifications. Conflicts were resolved internally to preserve the reputation of the community as a whole. Long-term cooperation, secured by the ongoing creation of mutual debt in exchange, was a necessary condition to this reputation system (Keshavarzian 2007, 17, 88ff.).exporters, wholesalers, retailers, brokers, and middlemen who make up the historic commercial class situated in urban centers and involved in diffuse, complex, and long-term exchange relations with the city, the nation, and international markets. (Keshavarzian 2007, 228)

The Iranian bazari offspring that arrived in Hamburg met a relatively favorable professional environment. The city already looked back on a history of several hundred years as an important northern European trading port. From the thirteenth century onward, Hamburg’s merchants were involved in a vast trade network, the Hanse . It connected important port cities in the area of the North and Baltic Sea to Western European and Mediterranean trade networks (Wubs-Mrozewicz 2013, 6). Interestingly, the structure of trade in this network had much in common with the social organization of the historical Tehran bazar. Indeed, the Hanse was not so much a formal trading trust than a shared concept. As in the bazar, commercial cooperation was based on a system of reputation. Similarly, this involved mutual monitoring through multiplex long-term relations with shared values tying merchants together (Ewert and Selzer 2009, 5ff.). Here, too, kinship, marriage, and fictive kinship were the social glue holding together long-term cooperation (Ewert and Sunder 2011, 6). In Hamburg, the mercantile spirit survived after the decline of the Hanse in the seventeenth century (Wubs-Mrozewicz 2013, 14f.) and its incorporation into the German Reich in 1871, thanks to the ongoing economic activity and strong political influence of a restricted number of highly interrelated mercantile and legal bourgeois families. Thus, they successfully asserted their position against the aristocracy, the military, and intellectual elite until the early twentieth century and were attributed important political positions after the fall of the German monarchy in 1918 (Evans 1991, 120–35).

In sum, shared professional ethics facilitated the insertion of Iranian merchants in the local economy. In the social organization of local and Iranian merchants, kinship relations were central. However, as we will see, the relations of Iranians with Hamburg’s well-established merchant houses rarely went beyond professional activities, at least for the first generation.

Pioneers in Flexible Capital Creation

After World War I and Shah Reza Pahlavi’s coronation in 1925, Iran and Germany, under the Weimar Republic, increased their bilateral relations out of mutual interest: the Shah’s cooperation with Germany, an industrialized country with only a minor colonial past, was part of his intention to undermine the British and Russian influence in Iran (Azimi 2008, 111f.). The Weimar Republic, in turn, was in search for an independent trade partner that exported raw material and provided a market for German manufactured goods. Although, from 1929, bilateral trade relations were endangered by a trade imbalance deriving from the Great Depression and political scandals (Mahrad 1979, 21–50; Digard et al. 2007, 75), it was in this context that the first Iranian merchants set up businesses in Hamburg.9

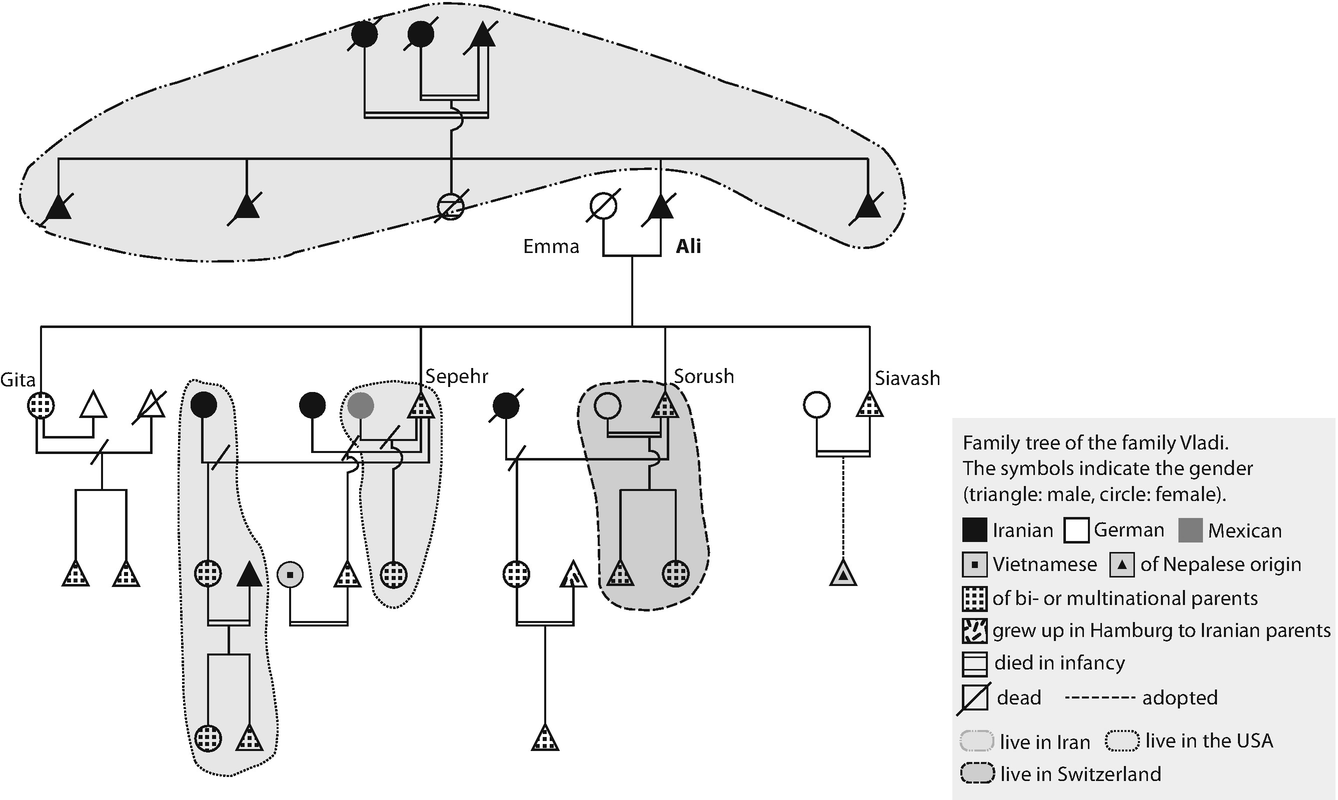

Ali’s family tree, all non-specified people live or lived in Germany

Ali was a teenager when his father died, but, according to his children, it fell to him to ensure the financial survival of the family. Their observation hints to the fact that, not least through his education, Ali defied the typical hierarchy of sibling groups structured by order of birth (and gender, if applicable) (Kuper 2004, 212). He entered the bazar economy with only a modest capital and when he was in his early thirties and unmarried, the self-made man started to work for an Iranian merchant in Hamburg, traveling back and forth to maintain contacts with trade partners. Iranian trade houses came along with their own social and professional hierarchy, with import-exporters at their head, followed by managers (Geschäftsführer, Prokurist), scripts, and other clerks (Keshavarzian 2007, 78ff.). I learned from archival material (Lisowski 03/11/194710) and from my interlocutors that it was usual practice for newcoming Iranians like Ali to first work for one of the established bazaris, and, once they had gained sufficient social, cultural, and economic capital, open their own merchant house. Indeed, in 1933—four months after Adolf Hitler became the chancellor of Germany—Ali finally set up his own business. His Iranian nationality thereby did not pose a problem, as Iranians were considered Aryans according to the Nazis’ racial ideology (Abrahamian 2008, 86). “Luckily they did not know that, as an Azeri, he was an ethnic Turk”, Siavash commented with a wink.

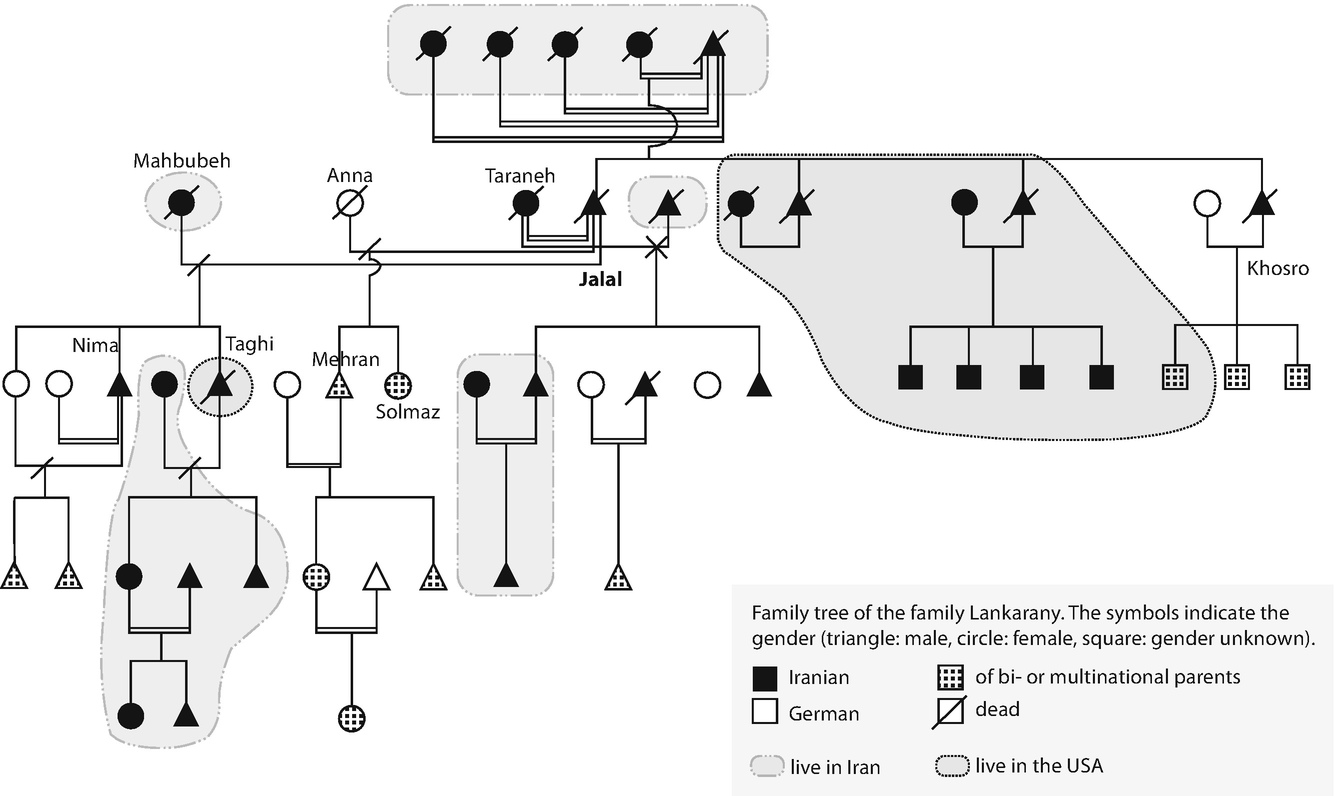

Jalal’s family tree, all non-specified people live or lived in Germany. The data for the extended family is simplified for reasons of pertinence

Thus, Ali and Jalal both came to Hamburg in the context of dynamics Aihwa Ong calls “flexible citizenship”, that is, “the strategies and effects of mobile managers, technocrats, and professionals seeking to both circumvent and benefit from different nation-state regimes by selecting different sites for investments, work, and family relocation” (idem 1999, 112). Accordingly, to pursue their career in Hamburg and create economic capital, they built on social capital, in particular on family reputation, kinship, and friendship ties they had at their disposal in the transnational social fields of Iranian merchants.

German Alliances?

Of course, Ali and Jalal did not only strive to create capital in transnational, but also in local social fields. In their professional life, they conducted business with German merchants, and in the private domain, many married German women. Which German women?

Indeed, marrying a local, even across ethnic and religious boundaries, ideally, marrying into a local merchant family, was a frequent practice in certain historical merchant networks, such as those of merchant families from Ladakh. Such unions do not only secure the acquisition of locality-specific resources for the next generation, but also create new social resources through the spouse’s relatives (Fewkes 2009, 75ff.; see also Curtin 1984). However, marriage practices were sometimes restrained by local social and political prescriptions that aimed to ensure the temporary nature of trade colonies (Van 2011, 276ff.). It is striking that, in Hamburg, most German women who married early Iranian merchants were of rather modest background. This was the case of both Emma and Anna, the young German model Jalal married in the early 1950s. Following Bourdieu, affinal relationships “are the product of strategies oriented towards the satisfaction of material and symbolic interests and organized by reference to a particular type of economic and social conditions” (idem 1990, 167). To better situate Ali’s and Jalal’s marriage, let us consider the different parties’ interests in these alliances.

Gita “There was the consul who was in office at the outbreak of the war, Abol Pourvali, and his German wife Gabi.”

Sonja “He had a German wife?”

Gita “Yes, she was an employee at the consulate (Konsulatsangestellte) and then he married her […]. In the Mittelweg [street in the upper middle-class neighborhood Harvestehude] lived the Daroga family. He was Persian, she was German and they had a daughter whose hair was blond […]. That was in [19]46, [19]47. Then, there was a certain Mister Chaichi, who had married a German from Peine, near Hannover. They married in Hannover – in Peine, and we were invited. I think the woman was from a patissier family.” (Interview, March 2014)

Drawing of the villa Parviz inherited from his German parents-in-law. (April 2014, author’s photo)

Christmas 1938 and Emma’s mother’s place. From right to left: Emma’s sister’s husband, Ali, Emma’s sister with Gita, Emma, and her mother (Siavash’s family archives)

Finally, expatriation offered young Iranian merchants a greater freedom for making the marriage of their choice. At that time, it was usual in Iran for marriages to be arranged according to family interests, in particular among merchants14 (Keshavarzian 2007, 95). An important factor in Ali’s life was, according to his children, his wish to move back to Iran, which he maintained almost until his death. In the face of the restrictiveness of the local Iranian marriage market, Emma was a good choice for Ali. As she was not from a local merchant family, she was not likely to expect Ali to participate in their sociability. Moreover, although marrying into a German merchant family would have offered important opportunities for capital creation, a daughter of a well-established family may not have been open toward a return migration. Thus, even though this marriage did not immediately provide him with economic resources, nor with German citizenship15 (cultural capital), becoming a head of family offered him the possibility to inhabit an image of a responsible adult, which increased his trustworthiness (social capital) among merchants.

Importantly, although Ali and Jalal both married Germans, they constructed their families around Iranian identifications for two reasons. First, there was a strong social cohesion among merchants of Iranian origin that relied on multiplex relations in which professional ties interweaved with kinship, friendship, and neighborly ties. Siavash told me that most Iranian merchant families settled in the same district, Harvestehude, which was also popular among local merchants. They had their office in the city’s commercial center, and only their stock houses at the warehouse district. These links build largely on their identification as Iranian, and they represented their business’ competitive advantage (see Chap. 3 for a detailed discussion).

Second, German society posed limitations to migrants’ inclusion (Aumüller 2009, 191). As mentioned earlier, German wives had to take Iranian citizenship. Consequently, their children had Iranian and no German passports. Reminiscent of the introductory quote to this chapter, when Ali and Jalal founded their families, a differentialist approach to immigration prevailed in Germany. Migrants’ cultivation of difference was tolerated as it was seen as a guarantee for their return migration16 (Brubaker 2001, 537). Thus, Hamburg’s society conceded pioneering Iranian merchants Iranian at the expense of German identifications.

The perception of these Iranian identifications was shaped by the German economic interest in trade with Iran, the people’s fascination for the “exotic” coexisted with xenophobic and racist tendencies. Parviz, for instance, told me proudly that once, while he was walking on the street, German passersby asked him whether he was from Hollywood. Siavash, in contrast, reported “When I was at school, there were always two swear-words: carpet trader and camel driver [Kameltreiber]” (interview, July 2013).

Having described the first years of Ali’s and Jalal’s life in Hamburg, I need to make a short digression from the analysis of kinship relations in order to explain the type of relationship the two men entertained with one another.

Why Ali and Jalal Were Not Friends

According to Sepehr, about ten Iranian (and binational) families and a few bachelors lived in Hamburg before the World War II. Given the small number, Ali and Jalal must have known each other. However, there is no record of an encounter, and their children do not remember the other family. To understand Ali’s and Jalal’s relation, I suggest considering their different ways to engage with political powers in their strategies of capital creation.

According to Siavash, Ali followed what he calls the “bazari mindset” (Bazarimentalität) in his political positioning: even if he did not agree with the political line of a government, thanks to skillful impression management (Goffman 1990), he pragmatically kept good relations with it in order not to endanger his business activities. He thus attended receptions at the Consulate General of Iran (established in 1934), and I could identify him on a picture at the celebration of Mohammad Reza Shah’s wedding at the General Consulate in Hamburg in April 1939, published in a local newspaper (Hamburger Fremdenblatt, 26/04/1939, no 115, Staatliche Pressestelle I-IV (1919–1954), 135-1 I-IV_4636, STAHH). There, he was able to meet not only government officials, but also scientists and German trade professionals17 (Hamburger Anzeiger, 20/04/1934; Hamburger Fremdenblatt, 20/03/1936; Hamburger Fremdenblatt, 16/03/194018). If we are to believe Parviz, he even ordered a carpet based on a portrait of Adolf Hitler to be knotted in Tabriz and offered it to the Führer in person.

Jalal’s political opinions had serious consequences on his opportunities to create capital. Although exchanges between Nazi Germany and Iran came to an abrupt end as the British and Russians occupied Iran in summer of 1941 (Mahrad 1979, 117–29, 181), he stayed in Hamburg during WWII. In October 1944, during one of the parties he frequently organized at his apartment, he critiqued Adolf Hitler. On the following day, one of his German guests denounced him to the authorities. Soon, the Gestapo arrested Jalal. They proposed him to spy for the German government. Jalal refused, was sent to the concentration camp Bergen-Belsen,19 and was only liberated one year later by the British army, heavily struck by typhus.20 Anticipatory flexible capital creation—he had set up a bank account in the name of his sons in Geneva, Switzerland, to where his friend Nasser took his assets at his detention—saved him from losing his economic capital (Lankarany 2009, 25f.). However, as we will see, this episode will not remain the only time Jalal’s proclivity to stick to his strong moral and political principles posed limitations to his capital creation.Luckily, father was not religious, but moralistic. He was totally politically interested. He also watched the news all day and only read nonfiction books, and newspapers, as long as he could still read. (Interview, July 2013)

For Ali’s part, when the war started, he took his young family to Tabriz. After a year and a half, Emma pushed toward returning to Hamburg. When, in the summer of 1943, their home and the company premises were struck by bombs, the family moved to live with Emma’s mother in the house Ali had bought for her on the countryside.

In the following decades, Ali continued to pragmatically maintain good ties with German and Iranian political power holders. Regularly, he and his family participated in receptions that took place in the local Iranian Consulate General and assisted, whenever possible, at events organized around Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s visits in Hamburg in 1955 and 1967. According to Siavash, his father also entertained good ties with Hamburg’s political and economic elite, and with highly positioned Iranian Shia clerics. These contacts were nourished not only through his thriving business but also through his leading role within the Iranian Shia Muslim community. In 1941, Ali co-established an Iranian Islamic burial ground21 in the city’s main cemetery, and from the early 1950s, he became the head of an association of merchants that advocated for and co-financed the construction of the Imam Ali mosque, which is today Germany’s second oldest still intact mosque (Verein der Förderer einer iranisch-islamischen Moschee in Hamburg e.V. 05/05/1955; Jess 10/01/195822).

For his part, Jalal followed invitations on the occasion of the Shah’s visits, as archival sources confirm (Hüber 11/02/1955; Hüber 15/02/195523), but according to his daughter without Ali’s fervor. Moreover, while Jalal showed himself very generous with his family and friends, he was not particularly interested in entertaining ties beyond this circle. From the mosque, he kept a critical distance as, according to Solmaz, he was an atheist.

Discrepancies between Ali’s and Jalal’s strategies of capital creation are thus apparent in the way they deal with political and religious power holders. They certainly reflect distinct personal values (for instance, political integrity versus economic security), which however interact with their unequal starting position: while Ali made private and professional alliances with the zeal of a self-made man with modest family resources, Jalal’s privileged upbringing may have contributed to him being more reckless in social relations, in particular with the authorities. On the basis of their divergent values, they strove to create capital in different social fields—and their interests did not coincide. Thus, foreshadowing an argument that I develop further in the following chapters, shifting boundaries among migrants not only depend on their trajectories in the country of immigration, but also on the compatibility of their engagement and respective positionality in local and transnational social fields.

To resume the discussion, Ali and Jalal’s different values were also reflected in the way they practiced kinship. Let us first consider how they involved their siblings living in Iran in their transnational strategies of capital creation.

Brotherly Ties Between Solidarity and Rivalry

Ali and Jalal (re)built their transnational businesses in the years after the World War II, that had left Iran with a new Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, and a highly damaged economy (Mahrad 1979, 189ff.), and Hamburg, under British occupation, in destitution and shortage of essential goods (Sywottek 1986, 384). By the early 1950s, the newly founded Federal Republic’s gross national product reached its pre-war strength, and economic growth remained unbroken until the mid-1970s—a phenomenon that became known as the “economic miracle” (Wirtschaftswunder) (Abelshauser 2004, 275). In 1951, Iran and Germany resumed their diplomatic relations, and the Federal Republic returned to being Iran’s most important trading partner (Adli 1960, 290; Mousavian 2008, 15f.). The favorable economic conditions represented an important upswing in the German society. During these years, Jalal and Ali became successful entrepreneurs, managing five to ten employees, including German tax advisors and accountants—but sought different relations with their transnational family.

Around 1950, Jalal opened a factory for electrical accessories24 with the newest German technology in his hometown Rasht, in addition to the import-export business he ran in Hamburg. Thereby, he made his 17-year-old younger brother Khosro, who lived with him in Hamburg since 1946, an associate of the stock company. He also distributed further positions and shares among family members living in Iran. Jalal’s involving of family members living in Iran corresponded to the primordial role of the family within the Iranian bazar economy discussed earlier.25 For him, it was a means to create trust from the important obligations deriving from exchanges in kinship relations (Sahlins 1972, 191ff.) and, at the same time, claim his role as the head of family after his father’s death. While both brothers took over formal responsibilities in the transnational businesses, Jalal charged Khosro with business administration, while he himself had a more laid-back, representative role26 (Lankarany 2009, 144f.). As in many other places in the world, according to Christian Bromberger, in Iran the family is at the core of the social organization. Strong solidarity may develop between brothers, but it implies constant social control (Bromberger 2005, 136ff., see also idem 2013, 124ff.). Similarly, Pierre Bourdieu (1990, 170) states that “the closest genealogical relationship, that between brothers, is also the site of the greatest tension, and incessant work is required to maintain solidarity”, that is, it is necessary to manage the tensions that may arise from conflicts of interest over the same resources. In Jalal’s family, it were such conflicts, growing from contradictory strategies of capital creation, that put into question the brotherly solidarity—but I am getting ahead of myself.

Thus, contrary to Jalal, Ali did not include his brothers into his business activities. Instead, he integrated first his close friends,27 and later, his children and affines into his strategies of capital creation. It is the analysis of the merchants’ relations with their wives and children that the following paragraphs are concerned with.I remember my two brothers went to Iran once by car via Turkey, that was 1965, 1968. They carried a letter from my father to his brother, which featured – after many polite introductory phrases – apparently also a phrase whose essence was ‘When do I get my credit back?’ There is a photo of my brothers showing him the letter. (Interview, March 2014)

The (Image of the) Nuclear Family

From the late 1940s, not just Ali, but also Jalal needed to fulfill the role of the father: Jalal’s family had joined him in Hamburg. Soon, his wife Mahbubeh returned to Iran and the couple divorced, but his teenaged sons, Nima and Taghi, stayed with Jalal (Lankarany 2009, 24ff.). After a few years—Jalal was already in his late forties—he got to know Anna, a blonde and beautiful German model, by more than 20 years his junior. In 1952, they married and had a son, Mehran, and in 1955 a daughter, Solmaz.

By then, both Ali and Jalal had come to considerable wealth. But, as Bourdieu (1985, 725) argued, in order to claim upward social mobility, economic capital must be sustained by the acquisition of social and cultural capital relevant to the specific social field. Thus, beyond their economic activities, to generate such capital forms, the merchants invested, first, in conspicuous consumption: both Jalal and Ali bought prestigious villas in upper-class districts, which they decorated with antique furniture, art, and craftwork. On the weekends, they went to a casino at the Baltic seaside resort Travemüde,28 and they drove expensive and rare cars. Ali took his family on holidays abroad, and Jalal bought a newly built prestigious nightclub (Lankarany 2009, 33, 48). Second, euergetism was another means both used to create capital: as mentioned earlier, Jalal would support his friends and family29 while Ali invested into the establishment of religious and social institutions for local Iranians. Conspicuous consumption and philanthropy had two purposes. On the one hand, following Aihwa Ong (1999, 92), they constituted an attempt to overcome barriers to capital creation they met in German social fields, that relate to their lack of Germany-specific capital or their construction as cultural and racial Other. On the other hand, similar to Pnina Werbner’s (1990, 304ff.) observations among people of Pakistani origin in Manchester, such practices aimed at creating capital through the mediation of values such as trustworthiness, financial strength, and religious adherence within the social fields of Iranian merchants.

Siavash’s description points to how the nuclear family participated in these events in different ways, according to their position in the age hierarchy and their gender. In Jalal’s family, the participation of the wife and children was less codified, certainly because, in contrast to Ali’s family, it was characterized by many personal and geographical ruptures, but the main lines were similar.

Siavash “Who busses the dishes? The two youngest. Sorush and I. We did not even dine with the guests but we came and went, dished up and bussed. And after the chicken broth, there was chelo kabâb [kebab with rice]. My mother delightfully knew how to prepare the meat beforehand. We had a Maghal, today that’s called a barbecue, right, flown in from Iran. And then, we had a housekeeper from Bavaria… the old women always touched the red-hot coals with her bare hands! Ouch! Sepehr, as the oldest, had to grill.”

Sonja “And Gita?”

Siavash “She ate with the guests. As a girl she had to… Or she helped mother fill up the rice.” (Interview, July 2013)

Thus, similar to wives in British Pakistani families (Werbner 1990), Iranian merchants’ wives represented the family’s real or aspired social position and contributed, through their socializing, to the generation of the family’s resources and recognition thereof as capital.Even when I was little and I think also before I was born [Jalal] lived in a huge apartment where he also always had guests. My mother naturally had to help hosting all people, who sometimes moved in there for months. (Interview, July 2013)

Siavash also said that during meals his father always sat at the top end of the table and expected his children to hand him whatever he wanted only by looking at the object. Following the principle of filial piety, initially the children accepted their father’s plans. Retrospectively, Nima remarks “Although I was self-confident otherwise, resistance was inappropriate for an Iranian son. You had to obey, it was as simple as that” (Lankarany 2009, 37).…he was a typical Persian patriarch, strict and barely accessible for his children, much less than for his friends and other people who asked something from him or who needed his help. (Interview, July 2013)

Jalal, for his part, was not as meticulous in planning and integrating his children in his businesses as Ali, but he projected that his second and third sons Taghi and Mehran would become entrepreneurs. Generally, however, expectations and pressure did not weigh as heavily on the younger ones as it did than on the first-born sons.In fact, he sent his import-export goods with a Persian shipping company, and he said, perhaps he trusted an Iranian more than a German shipping company, but it would be much better still to have his son on the ship as a captain, in order for the wrong goods not to be transshipped in the wrong harbor [he laughs]. (Interview, March 2014)

Gita was not as explicit in her description of the father’s control over her everyday life. As we shall see later, she had her own conflicts with him, but also enjoyed some protection from her mother that Solmaz lacked. The increased attention to the daughters’ (sexual) life serves to guarantee the family’s collective capital creation: in Iranian as in many other contexts, and in particular within the tight social networks of merchants, the family’s honor—her reputation—had (and still may have) an important influence on their kin’s possibilities of gaining acknowledgment for their resources as capital (Bromberger 2003, 87).

Solmaz “Actually, I was allowed to have only few contacts to the outside. Female friends some, but I had to ask permission if I wanted to leave the house.”

Sonja “Really? That strict?”

Solmaz “Yes. I had to be at home at eight [o’clock] sharp. At eight sharp the Tagesschau [news] starts. If I arrived later, I got into terrible trouble. Then, there were curfews. He was really terrible in this regard.” (Interview, July 2013)

In sum, having a wife and children in Hamburg came to play a crucial role in Jalal’s and Ali’s strategies of capital creation. On the one hand, the men used their wife and children to display economic, cultural, and social resources and claim recognition for them as a capital. Even the image of the family itself can generate capital: in founding a family Jalal and Ali stressed their availability to establish long-term business relations in Hamburg. On the other hand, the merchants also delegated capital creation to their children in practices Ong (1999, 118) calls “family governmentality”. Based on the idea of a common interest in the family business, heads of family arrange or promote, through the exercise of patriarchal authority, educational, professional, and migratory trajectories; physical appearance; and, as we shall see, marriage alliances in order to circumvent legal and bureaucratic limitations posed by nation-states. The professional and private roles and opportunities the merchants’ children were thus attributed depended on their age, gender, and place in the birth hierarchy. As they grew older, these differentiations within the family were renegotiated.

Dissent, Death, Disruptions

Just as trust in kinship relations can be very beneficial to business success, it can also be the cause of failure (Werbner 1990, 75f.), namely, when intersubjective conflicts lead to voluntary disruptions. Jalal had to learn this the hard way. It all began when his wife Anna left him in 1959, after seven years of marriage. Solmaz explained that her mother could not suffer Jalal’s year-long stays in Iran. Moreover, she experienced rejection from his mother and sisters. Just as in his business strategies, outraged Jalal relied on transnational family ties to resolve the situation. According to Iranian family law, custody falls to the father. Consequently, he took Mehran and Solmaz to Tehran to be fostered by his mother and sister—an experience Solmaz describes as traumatic. He did not allow them to see their mother again until 1967. One year later, in 1961, Jalal married his third wife, Taraneh, a widow from Rasht who had three sons—the youngest of whom was Mehran’s age. The newly composed family moved into the villa in Hamburg together.

Nima failed a study program in which he had enrolled. Then, he refused the marriage Jalal arranged for him with a young woman from another merchant family living in Iran. Instead, he entered a business school and married his German girlfriend. Jalal even bribed the Iranian consul in Hamburg to impede on this marriage, unsuccessfully (Lankarany 2009, 41–51). His second son, Taghi, returned to Tehran in the early 1950s (Lankarany 2009, 36–51), but he never became successful with his business projects. He is the only one of Jalal’s biological children who married an Iranian, but the couple divorced later and Taghi moved to California where he died of surgical complications in early 2010. His children remained in Iran and his daughter married an Iranian. Nima’s and Mehran’s children remained in Germany and the only marriage among them is with a German. Mehran, the third son, graduated with a PhD in Iranian Studies in 1983, and only later followed the father’s idea in funding a modest merchant business. Solmaz resisted Jalal’s plan for her to study medicine. In 1973, she dropped out of school whereupon he evicted her from the family home. During many years, she made a living with unskilled jobs, until she became a foreign language correspondent clerk. She never funded a family. Thus, one by one, Jalal’s children dropped out of the roles Jalal had assigned them to in his flexible capital creation.36It actually did not work out as he had imagined for any of his children. My father’s siblings are all quite well off I think, but nobody of us, his children, did what he had fancied he’d do. Thus, [we were] all losers, in a way, in his view [she laughs]! (Interview, July 2013)

Compared to Jalal, Ali was more successful in realizing his plans: his marriage remained intact, his first-born Sepehr worked in his company and moved to Iran in 1967 for a marriage Ali had arranged for him with the daughter of a successful entrepreneur. He founded a new business with his father-in-law in Iran, which aimed at saving the ailing family business. Ali’s younger sons negotiated professional trajectories that slightly deviated from his original idea, but that did not cause major relational issues. All was good—if it was not for his daughter Gita. While Ali tried to marry her to a young Iranian business partner established in Tokyo, Gita became engaged to her Spanish teacher—who was a German and a practicing Catholic. Acting against Ali, Gita left the family enterprise in 1962, when she was 24 years old, and worked as a secretary in Barcelona. “I won’t let them marry me off!” (interview, March 2014), she comments in retrospect. Only Emma, her mother, attended Gita’s wedding two years later. Ali had probably convinced his sons to participate in a collective punishment for this transgression. Solmaz also used an intimate relationship to defy her father’s patriarchal control: as a teenager, she engaged in a seven-year relationship with her youngest step-brother. It becomes clear that marriage alliances, in particular for their first-born sons and their daughters, were an important tool for Ali and Jalal to diversify their resources and generate new capital among Iranian merchants. Deviations from these arrangements were thus often met with drastic renegotiations of kinship relations. The fact that neither Ali nor Jalal encouraged their children to marry a German—let alone to marry into a German merchant family—is emblematic of their ongoing concentration on capital creation in transnational rather than local social fields, even 20 years after their immigration.

These negotiations within the transnational family, which Bryceson and Vuorela (2002) call “frontiering”, led, in the case of Ali’s relation with his younger sons, to minor mutual adjustments that allowed to maintain the original project, not least thanks to the first-born’s compliance with his own role.With that humanistic education I was very far away from my father’s world. That’s how a family drifts apart. Father said “We are Iranians, we go back.” For me that wasn’t even up for debate anymore. In school there was no other Iranian […], and, although I had one or two Iranian friends, for me this never implied an integration into the Iranian colony in a narrower sense. (Interview, July 2013)

Second, the more dramatic voluntary disruptions in Jalal’s family (Nima and Jalal severed contact for decades) may be traced back to deception deriving from a disequilibrium in relations of exchange (see also Zontini 2009). For the (financial) support the father offered, he expected his children in return to play the part he had assigned them to in his strategies of capital creation. However, the pressure of Jalal’s expectations, combined with an often unfulfilled need of financial, and, more importantly, emotional support—accentuated by the absence of a caring mother37 (Attias-Donfut 2000, 673)—led the children to resign from an exchange which they experienced as a poisoned gift (Mauss 1966).

As a consequence of this dissent, Jalal’s rebelling kin disengaged from the collective project of flexible capital creation and invested new social fields in which they follow their own strategies of capital creation. Their individualization resulted in a loss of important resources for the family business. His children each began to fend for themselves. In the early 1970s, Nima and Taghi’s resources were unavailable, unapt, or insufficient to prevent Jalal’s bankruptcy. Furthermore, these disruptions durably destabilized their practices of kinship. While some of the children tried to negotiate new terms to their relation with Jalal, repeated conflicts among the siblings, not least about financial issues, prevented them from recreating a collective project of capital creation.

Emma, who lost all financial resources, broke with her old role as a family mother, worked as a nanny in Southern Europe for many years, and never reinvested in Iranian social fields again until her death in 1999. As the formal successor, Sepehr took over Ali’s highly indebted company, but lost it together with his businesses in Iran in the context of the Islamic revolution in 1979. Two marriages with women in Iran ended in divorce. Finally, he settled with a Mexican woman and made a modest living as a carpet retailer in Eastern Germany before the couple moved to Florida where he collaborates in a real estate business with Sorush. Indeed, it was his younger brother who ended up continuing the father’s professional heritage. Sorush became a multimillionaire with an international real estate agency he founded in 1971, whose premises in Hamburg are just next to where Ali’s office was. Also, after a first union with an Iranian based in Austria, he married the member of a well-established Hamburg merchant family as if to strengthen Germany-specific capital. The family moved to Canada and then settled in Switzerland. Meanwhile his first daughter reinvested Hamburg’s Iranian social fields and married the son of a local Iranian businessman of Baha’i faith38 in 2013. In his own way, Sepehr’s son also carries on the family history as a maritime engineer, and his first daughter’s two marriages were with Iranians based in the USA. Siavash moved to work as a geologist in the north German countryside, married a local, and adopted a son from Nepal. Gita lived with her family in the south of Germany until she divorced and returned to Hamburg while her two sons live in other German cities.Such a family, as it’s common among Persian families, is very much based on the head of family, and when he drops out then the whole barn falls apart, right? (Interview, July 2013)

Thus, after Ali’s death, his wife and children developed individually different strategies of capital creation, and certain marriage alliances and religious choices led to disagreements within the nuclear family. Yet, however great the differences between Ali’s children were, in contrast to Jalal’s children, they still create capital together. For example, Siavash organized Gita’s move to a retirement home in 2015, and he wrote an article in a German travel magazine indirectly making publicity for Sorush’s business. Sorush, on his part, supports Siavash’s cemetery project, and shared his wealth, for example, in inviting the whole family for yearly holidays. Thus, in a dynamic Trémon (2017) calls “flexible kinship”, despite disruptions, Ali’s children redefined and revived the collective flexible capital creation that Ali initiated in the transnational social field of Iranian merchants in new forms and in different social fields.

Descendants’ Positioning Toward Iranians Today

While changing values, inequality of exchange, and death led to voluntary and involuntary disruptions within the family and to the individualization of kin’s strategies of capital creation, these events also had an important impact on the way the merchants’ children engage with other Iranians in Hamburg, in Iran, or elsewhere. The two factors by which they explained their contemporary positionalities was, on the one hand, their father’s financial decline, and on the other hand, their experience of the practice of kinship as a child and their experience of kinship practice.

Interestingly, Ali’s first-born does not limit the experience of difficulties in capital creation among Iranian merchants to this particular social field. In our interview, Sepehr, who speaks German with an American accent, tells me “that he does not get along well with Iranians, with ta’ârof [the Iranian code of politeness]. That would not be much like him” (field notes, July 2013). Thus, he creates a boundary, distancing himself from his Iranian heritage. In doing so, he indirectly explains his failure in creating capital in Iranian merchants’ transnational social fields by his ethnic difference. What is the relation between experiences of kinship, Iranian identifications, and the engagement in Iranian transnational social fields?after father’s death, ties with Iranians broke. Even those who said at his tomb “Call on us if you need anything” never contacted us again. Although father did so much [for them]. (Field notes, July 2013)

Thus, Siavash’s identification as German aimed at generating capital in local German social fields. Significantly, he married a German of Christian faith. However, his comment shows that these identifications met the resistance of Germans who continued to construct him as ethno-racial “Other”. It was only when Siavash was in his early fifties—maybe as a reaction to the experience of being categorized as foreigner—that he engaged in relations with Iranians and other Muslims, as he renewed adherence to Islam. Building on the capital his father had created through charity work today, he is more involved in Iranian social fields than his siblings. For instance, he created an association for the maintenance of the Iranian lot of the local cemetery that had been created by Ali in 2017. His memory of failed support from Iranians after Ali’s death may have been gradually superseded by Iranian merchants’ and mosque clerks’ appreciation for the father’s engagement for the Iranian Shia community and its infrastructure.When I moved here, to the countryside, and worked for a public service the foreign was rather secondary, right? Other people approached me with it, but I didn’t make anything out of it myself. (Interview, July 2013)

As shown in the introduction, research on transnational social fields highlights the importance of migration- and location-specific resources for migrants’ capital creation in diverse social fields (Erel 2010; Cederberg 2015). Among Iranian merchants, to create capital Sepehr needed to have Iran-specific resources such as speaking Persian or Azari or knowing ta’ârof in order to create capital. Conversely, in the social fields located at the North German countryside where Siavash lived, he needed Germany-specific resources to create capital. The ethnographic material presented here, however, allows to extend the perspective on the men’s strategies of capital creation by their experience of filial and affine relations in the context of collective flexible capital creation.

After she broke with her father over her professional trajectory, she distanced herself from her family as well as from other Iranians for about 30 years and replaced her Iranian by a German citizenship. Her comments highlight what was subjacent in Sepehr’s and Siavash’s statements: the identification of the experience of kinship with anything Iranian. The association is reminiscent of the constructed dichotomies of nature and culture, the biological and the social, in particular in the context of kinship and ethno-racial differentiation (Strathern 1992; Wade 2007). It reminds us of the newspaper article cited in the introduction that showed that the children were hegemonically constructed as Iranians by the German legislation and by social discourses. We saw that different, yet similar structural limitation was imposed on them by their father’s family governmentality and ongoing efforts to integrate them into their flexible capital creation in Iranian transnational social fields.For me, [anything Iranian] was a real system of oppressors, right? At the time, it didn’t have the quality of a culture, or something beautiful, or so, but it really was a symbol of total oppression, and I simply had a total desire of freedom. When I moved out I wished, virtually, to be a German, I mean, I did not want to have anything to do with Iran. (Interview, July 2013)

Strikingly, however, the diachronic perspective shows that the memory or experience of kinship practices and the resulting strategies of capital creation are not fixed, but underlie temporalities; they change within the life course (Trémon 2017). Thus, similar to Siavash, it is Solmaz who, among the siblings, is closest to other Iranians, as she recently renewed contacts with some members of her extended family, occasionally goes to Iranian cultural events, and regularly visits a friend of her father who is still alive. She told me that, for the first time since 1974, she considers traveling to Iran. My encounter with them itself, their participation in this research and our discussion of an earlier version of this chapter is both an important testimony and element within this renewed interest of theirs.

In sum, the ethnographic material indicates that there is a triangular relationship between kinship, entangled ethnic, racial, or national identifications and strategies of capital creation. In other words, not only the positionalities migrants take within in-group relations and the ethnic and national identifications they put forward are interrelated; both strongly correlate with changing personal experiences of kinship practices.

In this chapter, I traced the ways two merchants mobilized kin to generate capital along conceptions of generation, gender, and age in order to explain how these experiences influence the descendants’ own national identifications and their positionalities in local and transnational social fields constituted mainly by Iranians. Similar to the dynamics within the well-established Northern-German merchant family described in Thomas Mann’s (1993 [1901]) chronicle The Buddenbrooks, Iranian merchants involved their siblings and children in their flexible capital creation in their professional transnational social fields.

As I trace the personal trajectories of kin over two generations, I go beyond Aihwa Ong’s (1999) premise of filial piety, showing how voluntary and involuntary disruptions of kinship relations impact on collective flexible capital creation. While involuntary disruption through death or the flexible adaption of kinship to the members’ changing values or socio-legal condition may result in the transformation of the collective project, voluntary disruption based on mutual deceptions may favor its dissolution and the individualization of strategies of capital creation.

I showed that, in a triangular relationship, the changing experience of kinship has a lifelong influence on migrants’ engagement in social fields mainly constituted by Iranians as well as on their national identifications. I thus argue for a greater consideration of processes of “doing kinship” and historically informed approaches both in the study of migrants’ internal differentiation and transnational capital creation.

Having closely examined professional trajectories of two merchants, in the next chapter my interest shifts to larger social contexts, as I look at the way carpet merchants of Iranian origin developed collective strategies of capital creation and how they influence social boundary-making among Hamburg’s Iranians today.

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.