A photo of four people, presumably a family, accompanies this text. Before the decorative background of a warehouse with piles of oriental carpets, the husband and wife, in their fifties, are positioned on the left side of the picture and the son and daughter, in their early twenties, on the right. The two men wear costumes in dark colors with white shirts and shiny beige and blue ties, sporting confident toothy smiles. The son’s left hand is in his pocket, demonstrating effortless assurance. The women, instead, display a retained smirk, wearing a blazer and a pullover with a fur-trimmed collar. The mother also wears full hijab that covers her neck and hair, while the daughter’s long, dark hair is tied back. The image twines generational continuity with familial unity through similar postures. Gender roles appear to be shaped by patriarchal and Islamic principles, as they show in the men’s élan and the women’s modest demeanor and dress. The photo reminds me of the pictures of Ali’s family in Chap. 2. It puts forward an Iranian identification, family cohesion, a long history in Hamburg as proof of business continuity and expertise, and (in this case) also religious adherence.In 1968, Farhad F. settled in Hamburg’s free port as an importer and specialist for hand-knotted carpets, perpetuating the tradition of the carpet trade in the second generation. Today, the branch in Hamburg’s Speicherstadt, with its 1000 m2 show room, is managed mainly by the third generation. We offer a large assortment of hand-knotted carpets. (Section “company” on a merchant house’s website, anonymized, translation by the author)

As I got to know more and more Iranian carpet merchants during my fieldwork, I was struck by the observation that, although their business strategies may be quite diverse, they offer very similar identitary discourses both in immediate contact with me and in their media publications. The above online presentation of a merchant family business contains its main elements. How did this collective narrative develop?

Resources that sustain an ethnic or national identity may be useful for avoiding barriers to capital creation in the social fields related to the country of residence, as they allow migrants to withdraw from the main labor market (Moallem 2000; Bauder 2005). Otherwise, through “identity entrepreneurship” (Brubaker and Cooper 2000; see Erel 2010; Nowicka 2013), these resources can serve to create capital within social fields of the society of residence. Research that traces such practices in transnational contexts largely focuses on the practicalities of migrants’ juggling resources across social fields. Yet, what motivates their strategies of capital creation? Considering, with Joel Robbins (2015, 28), that social actions is, in complex and sometimes contradictory ways, motivated by values, I draw on the anthropology of value to answer this question. In the introduction to this book, I argue that capital creation relies on evaluation processes; evaluation processes take place in historically rooted hierarchical systems of value (Graeber 2001). The notion of value thereby refers to “ideas about what is ultimately important in life” (idem 2013, 224). Although extant research on migration reveals the evaluation of migrants’ resources in the society of residence, we know very little about the way systems of value interrelate within and across different social fields. Ultimately, what is migrants’ potential for action within the diverse, partly contradictory systems that define the value of their resources?

In Chap. 2, I demonstrated that they flexibly adapt their strategies of capital creation to changing socio-economic and legal conditions across national borders (Ong 1999). The analysis of kinship relations within the entrepreneurial family showed that individual ethnic and national identifications are both tools and expressions of strategies of capital creation within contexts of structural limitations deriving from unequal power relations. In this chapter, I analyze Iranian merchants’ collective identitary narrative as a tool in and a reflection of transnational capital creation and problematize transnational capital creation as part of migrants’ creative engagement with systems of value.social actors who enact networks, ideas, information, and practices for the purpose of seeking business opportunities or maintaining businesses within multiple social fields, which in turn forces them to engage in varied strategies of action to promote their entrepreneurial activities. (Drori et al. 2010, 4)

Building on participant observation, archival material, media analysis, and oral history interviews, the aim of this chapter is to explain how the collective identitary narrative of the “traditional Iranian merchants” engages with systems of value that prevail within and across social fields related to the local German market, the Iranian government, and the transnational networks of Iranian merchants under changing local and global economic and political conditions from the 1950s until today. The shifts of value caused by the Iranian revolution in 1979 and events surrounding the political and economic crises since the mid-1990s highlight merchants’ possibilities and limitations to navigate structural inequalities and contribute to their boundary-making from newcoming Iranians. As they occupy a gatekeeper position in the context of international economic sanctions on Iran, the discussion of this chapter offers reflections on relations between single values within the same system and between different systems of value. But let me first give you an idea of the setting.

The Ethnographic Frame

On a sunny day in June 2013, I take my bike to the former free port to meet Akbar, a carpet merchant, whose contact I obtained through Abtin, the Iranian owner of a high-end restaurant. Akbar is at the head of a transnational carpet merchant enterprise.

View on the warehouse district (Speicherstadt ) from the Poggenmühlenbrücke. (June 2013, author’s photo)

Street view in front of Akbar’s store. (June 2013, author’s photo)

Akbar’s show room with view on a fleet. (June 2013, author’s photo)

Tea set from Iran on a hand-knotted Persian carpet. (June 2013, author’s photo)

While we wait for his father, Rahim tells me that his family is from Tabriz, the capital of the province of East Azerbaijan in Northwest Iran. Later, Akbar explains me that he first came to Hamburg in the early 1950s. From then on, he collaborated with Germany-based Iranian merchants, supplying them with carpets on consignment. It was only in 1981, after the Islamic revolution, that he asked for asylum in order to bring his family to Germany and establish his own business. Rahim relates that he started to work in the PR section of the family business, together with one of his sisters directly after his graduation from high school. Just like in the time of Ali and Jalal (Chap. 2), the transmission of the business within the family is still a frequent practice among Iranian merchants. Rahim and his father travel to Iran several times per year; during these trips they combine private visits and the entertainment of—“multiplex and crosscutting” (Keshavarzian 2007)—transnational relations with colleagues and trade partners. Marriage still sometimes reinforces these ties: Rahim’s wife grew up in Tabriz. He also tells me that he is a member of the two most important Hamburg-based Iranian professional associations, AICE and BIU (Union of Iranian Entrepreneurs).

While we talk, I observe a tall man in a gray costume in his eighties giving advice in Persian in a grave voice of authority as he supervises the delivery. We stand up to greet Akbar. I start introducing myself in German, but Rahim interrupts me, asking me to switch to Persian. Akbar does not speak German fluently. As we speak in Persian, I still struggle to understand him and thus discover an accent I did not know before, that of a native Azari speaker. Another man of Akbar’s age enters the show room. He also wears a costume. During my research, I witnessed several such spontaneous visits among established merchants. They also told me to pass by whenever I wanted and I found them available when I did so. Akbar talks to the visitor, apparently a long-term acquaintance, in Azari. Omid told me a few months later that Akbar nourishes strong ethnic identifications and is a skilled Azeri dancer. Indeed, due to chain migration, today many of the local Iranian merchants identify as ethnic Azeri (Rezaei 2009). Together, the men brainstorm names of early merchants to help me with my research. Beyond the similarities in identitary discourses, Akbar and Rahim’s associational affiliation, their acquaintance with Omid and the friendly visitor indicate that they belong to a group of merchants who follow collective strategies of capital creation. Let us examine the development of these strategies through a diachronic review of the way merchants engage with changing evaluation criteria in different social fields.

A Golden Age?

Although known in Europe since the Middle Ages, Oriental carpets have become a large-scale consumer good only since the late nineteenth century (Spooner 1986, 201ff.). In these early years, the international trade and, increasingly, the production of carpets were in the hands of European businessmen who collaborated and competed with merchants in Iran (Ittig 1992; Rudner 2010, 54). With the coming to power of the monarch Reza Pahlavi in 1925, the carpet industry became part of his enhancing of Iran’s national identity (Rudner 2010, 53). By the 1920s, carpets were Iran’s most important non-oil export good—which it remained until today (Amuzegar 1993, 150).

As political and economic links between Nazi-Germany and Iran grew stronger in the 1930s, Germany replaced the USA as the first export market for carpets (Rudner 2010, 73). In order to gradually evict foreign companies, the Pahlavi government nationalized the industrial production in 1936. In Hamburg, however, German import restrictions secured the market dominance of German entrepreneurs and granted only small carpet quotas to those Iranian merchants who traded cotton.

During these years, Iranian migration to Hamburg was dominantly mercantile4 (and male). Many of those who initially came for studies switched to the flourishing carpet trade. So did Parviz, the son of a bazari from Tabriz. He began to study architecture in 1951, just to become a carpet retailer in 1962. My interlocutors liked to describe the pre-revolutionary period (between 1950 and 1979) as the golden days of local Iranian economic and social life and contrast it with the contemporary situation. To understand why, we need to examine the systems of value that shaped the social fields that are relevant to their professional activity at the time.Hundreds of new carpet merchants live on the trade with “popular-Persians”. Shops opened in almost all big cities, on whose façades colorful neon tubes blink at night, bearing Koranic suras or Oriental names as Soraya, Mohammed and Ahmed Ali. In Hamburg, the biggest port of entry for carpets on the continent, more than 300 new carpet importers established themselves in the past few years. (Anonym 1961, 41)

As we saw in Chap. 2, creating capital in relations with the Iranian emperor, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, and, by extension, the social field of Iranian foreign trade relations, was crucial for merchants’ professional success. Significantly, Jalal’s bankruptcy was connected to his confrontation with the Pahlavi foundation. The Western model of modernity, prosperity, and secularism together with the pre-Islamic Persian cultural heritage—those were the values Mohammad Reza Shah set forth. The Iranian emperor largely refrained from intervening in the internal social system of the Iranian bazar (Keshavarzian 2007), but he valorized the economic importance of Hamburg’s Iranian merchants through two visits, in 1955 and 1967.

The way merchants participated in the program of the Shah’s visits shows how they engaged with the system of value that dominated in this social field. Siavash remembers having been made to wear (uncomfortable) local seaman’s clothes as he lined up with other Iranian merchants’ children to greet Mohammad Reza Shah on his arrival. Parviz praised the elegant festivities at the five-star Hotel Atlantik, which still is a popular location for celebrations organized by Iranian businessmen. He remembers how he shook the Iranian emperor’s hand during one of these receptions. Public media documentation of these events shows Iranian merchants next to German officials, all equally elegantly dressed in costumes and evening gowns (Norddeutscher Rundfunk 1955). For Parviz, the mastery of European ballroom dances was no obstacle, as he had learned them in Iran, before his emigration. Building on Bourdieu’s theory of inequality and Graeber’s concept of value (2001, 2013), I suggest that we create capital by putting forward resources that mediate values which are highly positioned in the system of value of a particular social field. In turn, it is through acts and discourses of differentiation that we disclose resources (Lambek 2013). Thus, in the social field of Iranian foreign trade, merchants boosted their capital creation by displaying resources that mediate values positioned highly in the Shah’s system of value.5

Research shows that the prevailing image of the country of origin influences migrants’ chances to create capital in the country of residence (Ong 1996; Henry 1999). In the poor, post-war Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), people were fascinated by the image of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s wealth and orientalist splendor. His second wife, Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiary, whose mother was German, regularly figured in the FRG’s tabloid press. So, Iranian merchants were both needed6 and admired for their financial strength and generosity in post-war Hamburg. Plus, as mentioned in the previous chapter, there was a certain fascination with the “exotic”, the Oriental and more particularly “things Persian” that is deeply rooted in European, and German, history and cultural productions (Said 1978; Dabashi 2015). According to Hamid Dabashi, in the German cultural context this fascination was shaped for instance by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s West-Eastern Divan (2010 [1827]) and Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zoroaster: A Book for All and None (2003 [1883–1885]). Significantly, an unreferenced newspaper comments about a basketball match in which Parviz participated from the mid-1950s: “we particularly liked the Persian [Parviz], one of the HSV’s [name of the team] numerous exotics”. Similarly, the pensioner told me that the owner of his preferred ball house called the table he used to occupy with his friends “the table of princes” (Prinzentisch).

In sum, between the early 1950s and the late 1970s, Iranian merchants could create capital in Hamburg’s society in as far as their Iran-specific resources mediated wealth and exoticism. Mayor Kurt Sieveking said in speech at the Senate’s reception during the Shah’s visit in 1955: “It is a special honor and a great pleasure for the Senate, the Bürgerschaft (Hamburg state parliament) and all the population of our city, to which we gladly count the members of the Persian colony in Hamburg, that the first visit of the royal couple on German soil begins in our city” (Sieveking 07/03/19557).

It is no coincidence that the Iran-specific resources which conveyed value in German social fields are the same resources the Iranian government promotes. In his analysis of laicity in France, André Iteanu (2013) shows that values may encourage certain kinds of political hierarchies. Indeed, Western countries, in particular the USA, played a critical role in putting and keeping Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi in power.8 His promoting values that correspond to Western systems of value signal an effort to maintain their political support, thus perpetuating their unequal global power relations. What is striking here is that, while Bourdieu (1997) claims that classificatory schemes that shape social fields embedded in a nation-state are largely independent from each other, we find parallels between these structures in social fields that are connected to different nation-states. Thus, some systems of value shape only one social field, and others transgress the fluctuating confines of social fields and influence conditions of capital creation across national boundaries.

The article ascribes fraudulent business strategies to social (i.e. poor students), cultural (i.e. Iranian origin), and, through the insistence on the sellers’ physical features, racial differences. In another article, itinerant carpet traders—former German army generals—express concern that the new Iranian competitors would downgrade what before was a “respectable business” (Kavaliers-Geschäft). If articles mention German participation in these practices, they do not condemn it with the same vehemence. Taken together, these articles draw the Orientalist image of the “carpet-crook” (Teppich-Gauner) or “Persian mat hawker” (persischer Matten-Höker), an untrained outsider to the business, who uses unfamiliar—and implicitly dishonest—methods10 to trick on the trusting customer, in order to suggest Germans to rely on serious and locally established (i.e. German) retailers or turn to domestic quality products, instead (Anonym 1961, 1971).There are many possibilities of fraud; rampant oriental fantasy steadily creates new ones. There is the lamenting student from Persia at the doorstep, who needs to keep his head above water by selling the “family heirloom”, of course far below the [market] price. And facing this seemingly so advantageous opportunity melts the carpet-addicted German’s appropriate mistrust. Or even the dark-skinned academic, maybe also the Iranian engineer temporarily working for the same company, offers a colleague a unique opportunity. (Bodendiek 1966, 3)

As the appellation “genuine Persian” suggests, genuineness, singularity, and authenticity determine a carpet’s symbolic efficiency for the customer. Between the lines, the articles say that the carpet’s authenticity can be measured by the merchants’ honesty and accountability. Yet, these values are subordinated to the value of familiarity; mediating familiarity was a necessary condition to displaying expertise and accountability. In German society at the time, Iranian merchants were constructed as the cultural and racial Other, while what was familiar was anything identified as German or at least Western.

Thus, in German social fields in the pre-revolutionary period, the reception of Iranian merchants was ambiguous. On the one hand, resources that mediated wealth and economic growth, as well as Iran-specific resources mediating exoticism, were valorized, which allowed merchants to create enough capital to establish themselves professionally. On the other hand, their perception as exotic contradicted the value of familiarity. What was exotic could not be familiar at the same time. This contradiction created a barrier to their capital creation, because resources that did not convey familiarity could not mediate honesty and authenticity.

Economic resources yes, migration-specific cultural and social resources no—Aihwa Ong (1999, 88ff.) reports that Asian transnational entrepreneurs meet similar barriers to capital creation in the USA. She makes an important contribution to Bourdieu’s theory of inequality by conceptualizing limits to capital creation: migration-specific resources that cause cultural and racial Othering constitute symbolic deficits, which impede on the recognition of migrants’ other resources as capital. The bringing together of Bourdieu’s approach to inequality and the anthropological theory of value offers a new understanding of the effect of evaluation on capital creation. We know since Louis Dumont (2013) about the hierarchical dimension of systems of value. To him, values are not only interdependent, but they are ranked. The fulfillment of certain key values determines the mediation of others. The discussion of Dumont’s work exceeds the objective of this book, but I follow Graeber (2001, 16ff.) in retaining that relations between values are vertical, besides sometimes being horizontal. Moreover, I distance myself from Dumont’s holist view and study systems of value not within societies, but within particular social fields. My historically informed ethnographic data suggests that, in the system of value that shaped the social field of the German carpet market at the time, familiarity was positioned at a higher position than exoticism or wealth. If Iranian merchants’ chances of capital creation were limited, it was because while their resources exuded exoticism and wealth, they failed to convey familiarity. Accordingly, it follows that limits to capital creation arise from the inefficiency to convey a value that is of crucial significance within a particular social field.

The transnational social field of Iranian merchants was where Iranians invested most of their efforts of capital creation, as I showed in Chap. 2. While foreign business partners were invited to receptions, Siavash told me that it was with the (binational) families of other Iranian merchants that his parents spend their free time. Even institutions such as Hamburg’s first Iranian restaurant, which opened in the mid-1950s, the “German-Iranian chamber of commerce” (Deutsch-Iranische Handelskammer), the “Union of Iranian Carpet importers” (Verband der iranischen Teppichimporteure, today called AICE), and the “German-Iranian Bank of Commerce” (today: European-Iranian Handelsbank), all founded by merchants between the 1950s and 1970s, catered to this transnational social field. In these contexts, Iran-specific resources such as fluency in Persian, religious knowledge, or close kinship, business or friendship relations with the members of highly recognized merchant families were valorized for mediating values of family cohesion, cooperation, accountability, selflessness, generosity, and piety (Keshavarzian 2007). Religious, social, and cultural rituals that mark the dense moments of Iranian merchant sociabilities play a key role in renewing their collective system of value over the decades (cf. Robbins 2015).

Foundation stone ceremony of the Imam Ali mosque in February 1960. Hamburg’s Senator Kurt Sieveking on the left, and Imam Hojatolleslam Mohammad Mohaghaghi on the right (Siavash’s family archives)

In sum, the bundling of individual interests within the transnational field of Iranian carpet merchants worked as a collective strategy to confront the barriers to capital creation caused by their difficulty to mediate familiarity in German social fields. In concurrence with extent literature in migration studies (Light et al. 1994; Bauder 2005), research of Iranian ethnic entrepreneurship in different Western countries points to the support this occupational form can play in countering discrimination and downward social mobility (Khosravi 1999; Moallem 2000). The merchants’ collective agency was sustained by their relatively small numbers, a common bazari background in Iran, and their participation in a system of reputation in which mutual trust and control relied on multiplex14 and crosscutting relations.

Utility vehicle of the merchant business Hassan Vladi, probably the 1950s (Parviz’ family archives)

Given the barriers to capital creation they met among Germans, why do my interlocutors see this period of time as particularly positive? As part of the narrative of the “traditional Iranian merchants”, the discourse of the “golden age” of thriving Iranian social life and the muting of experiences of discrimination were constructed retrospectively. They are an expression of merchants’ contemporary politics of value, to which two mayor historic developments largely contributed, as the next two sections will show.

The Iranian Government, the Flüchtling, and Illicit Business Practices

To understand the value shifts, let us keep in mind three issues: the Iranian government (Parviz’ silence is significant), refugees, and illicit business practices.

Sonja “How was it actually like when in 1979 the revolution happened? Many new Iranians came here. How was that for those who had been here for a longer time, like you?”

Parviz “Yes, many refugees [Flüchtlinge] came. They smuggled and… and other things, teriak [opium, in Persian in the original] and weapons and all. And until then were… Persians have had a good name, but after not anymore [sic!].”

Sonja “This changed then, but was that maybe also because of the new government in Iran?”

Parviz “Yes.” [he takes a sip of liqueur, a few seconds of silence]

Sonja “And then, new carpet traders came, too.”

Parviz “And came, and again, they didn’t make it, [and went] back [sic!].” (Interview, April 2014)

First, with the overthrow of the monarchy, the system of value that shaped the social field of Iranian foreign trade underwent drastic changes. Constructed in opposition to the Western-oriented monarchy, the new regime glorified modesty, religious piety, altruism, regime-loyalty, and family cohesion, while it rejected any idea or practice associated with the West, including conspicuous consumption and self-interest, as alienation and gharbzâdehgi (Weststruckness) (Khosravi 2008). It valorized the bazar and individual bazaris gained high positions in the government, namely those who had been important allies in the revolution. However, it sanctioned merchants who could not prove their adherence to the regime’s values, for instance through expropriation (Abrahamian 2008, 179; Keshavarzian 2009). Sepehr, Ali’s son, lost his businesses in Iran and fled to Germany for this reason. According to Oliya, Omid’s sister (one of the very few women I met who work in Iranian merchant businesses), it was not until Mohammad Khatami’s presidency (1997–2005) that relations between Hamburg’s Iranian merchants and the Iranian government stabilized.

The new Iranian government began to intervene in the bazar and new, overlapping hierarchical structures co-opted the old system of reputation (Keshavarzian 2007, 107; Sadjed 2012, 120–24). Religious foundations (bonyâd) became major economic players. They opened branches in Hamburg in the mid-1980s, offering a greater variety and more economic carpets than established merchants, thanks to their operating outside the bazar economy (Rezaei 2009, 92f.). Due to the government’s political ideology and the war with Iraq (1980–1988), restrictive and unstable foreign trade policies fostered corruption and smuggling (Digard et al. 2007, 250; Erami and Keshavarzian 2015). Consequently, merchants had to redefine their strategies of capital creation, but how they did this is not something people liked to talk about, as we can see in Parviz’ silence.

The man further states that his only daughter married an Iranian (i.e. not a German), while his sons are going to take over the family business in Hamburg, indirectly stressing that he had not become “weststruck” even though he lived in Germany since many decades (OPT1001 2012). Thus, the Iranian government hails the merchants’ staging of the moral, that is, socially responsible, businessman15 (Amuzegar 1993, 20ff.; Keshavarzian 2007, 54) and presents in him the portrait of the ideal migrant, who promotes the values it seeks to set forth. This image is reminiscent of China’s discourse on its overseas citizens (Ong 1999, 43).

“The real labor is with the weavers…”

Farhadian “I would really like to kiss the hands of all these artistic weavers from afar, and I just would like to tell them that it is only for you that I built this [carpet shop], to represent the outcome of your work at its proper value.”

Journalist “Exactly, this is your service to our culture, your service to our traditions, to our efforts, to our values. It represents the effort and work needed to bring an Iranian carpet, a handwoven rug, to a sales exhibition in the heart of Europe. Anyways, this is a demonstration of your attention to genuine Iranian culture.” (Translation by the author (OPT1001 2012))

what makes it so easy, in contexts characterized by complex and overlapping arenas of values, for so many actors to simply stroll back and forth between one universe and another without feeling any profound sense of contradiction or even unease.

Second, the revolution in Iran, the arrival of new migrants, and changes in the public perception of immigration influenced the values which Iran-specific resources mediated in German social fields. The hostage crisis at Tehran’s US embassy (1979–1981), the Iranian supreme guide Ayatollah Khomeini issuing a fatwa against Salman Rushdie (1989), and local repercussions of these international events, such as Iranian political murders on German territory: fascination with Iran’s Orientalist allure was replaced with estrangement and suspicion of its authoritarian, Islamic regime and openly anti-Western discourses (Hesse-Lehmann and Spellman 2004; Van den Bos 2012; Adelkhah 2016). While Germany remained Iran’s most important economic partner in the West (Bösch 2015, 348), it abolished the visa-free entry for Iranians. Thus, most newcomers passed through the asylum procedure—and there were many. Within a decade, Hamburg’s Iranian population quintuplicated to reach about 10,000 in 1990 (Helfer 1989).

Polemics around the notion of “asylum-abusers” (Asylbetrüger), who would take advantage of the social system, stirred resentments in the German society (Heinrich Lummer in Göktürk et al. 2007, 113f.). Parallelly, the exclusion of the cultural and racial Other became more pronounced. Significantly, when chancellor Helmut Kohl took up his duties in 1982, he declared wanting to send back half of Germany’s Turkish immigrants because, in contrast to Italian, Portuguese, or South Asian migrants, they would not adapt to the German society (tkr/DPA/DPA 2013). Through these dynamics, Iran-specific resources largely lost the value of exoticism; their new estrangement to Germans threaded to reinforce already existing barriers to merchants’ capital creation in Germany.

It is thus significant that, when we talked about Abtin, a successful restaurateur, Akbar qualified him as a Flüchtling (“refugee”, he said it in German!). By his tone, I could tell that he did not hold much regard for people he characterized as such. In contrast, he showed respect to the living and deceased members of early merchant families he had known. Just like Parviz and many other merchants, Akbar seeks to distance himself from newer migrants and mark his identification with early merchants, even more so because he himself passed through the asylum procedure. That different “vintages” of migrants may look at each other with suspicion is an important paradigm in migration studies (Kunz 1973; see also Lamphere 1992; Vertovec 2015). Research on Iranian migration in various destinations shows that the time of departure is a frequently used marker in internal boundary-making (Kamalkhani 1988; Kelley et al. 1993; McAuliffe 2008). This internal boundary-making is related to the fear of what Boris Nieswand (2011, 80ff.) calls “collective devaluation”. We can see it in Parviz’ reference to the “name” of Iranians in German society, which he claimed was good until the revolution. Merchants were afraid that their Iran-specific resources lose the value of exoticism.

Indeed, a similar orientation toward authenticity and the marketing of ethnicity can be observed in many areas, such as art, tourism, and food (Comaroff and Comaroff 2009; Cravatte 2009; Grasseni 2005). We saw that authenticity was already an important value in the German carpet market before. However, its mediation was tied to the mediation of familiarity. What had changed was that Iran-coded commercial and personal practices and objects increasingly mediated authenticity. In other words, the same Iran-specific resources that accounted for Iranian merchants to be considered unfamiliar and untrustworthy in the 1960s came to mediate values that were efficient at generating capital by the 1990s. Simultaneously, merchants set forth their long-term presence in Hamburg in their collective narrative, because this resource began to mediate familiarity, reliability, and accountability. Significantly, a documentary movie from 1989 attributes the persistence of the warehouse district to the ongoing economic activity of Iranian carpet merchants and underlines not only their Iranian ways of doing but also their local rootedness and their keeping alive local merchant tradition (Helfer 1989). Interestingly, the otherwise very different system of value in the field of Iranian foreign trade intersects in the valorization of authenticity through its hailing of modesty and craftmanship. Hence, merchants’ politics of value within the social field of the German carpet market contributed to modifying the dominant system of value.the more artificiality, anonymity, and uncertainty apparent in a postmodern world, the more driven are the quests for authentic experiences and the more people long to feel connected to localized traditions seeking out the timeless and true.

Finally, Parviz describes newcomers’ business strategies as illegal and amoral, hinting to the fact that new immigrants’ resources did not mediate the values relevant in the transnational field of Iranian merchants. There were two types of newcomers. First, there were Muslim Iranians who, according to Omid, were embedded in the bazar’s system of reputation and acquired the companies who were sold because of supply difficulties or because their owners were Jewish Iranians who quit their business in the aftermath of the Islamic revolution. Conforming to the values of this social field, they could generate capital and were quickly integrated (Rezaei 2009, 89).

The second type of newcomers who turned themselves into merchants and retailers lacked of social relations in bazar networks. Behruz’ father (Chap. 5), for example, had been a lawyer in Iran. As his diploma was not recognized in Germany, he established himself as a carpet merchant. In contrast to the family businesses of established merchants, most of these self-made merchants or retailers built on short-term cooperation and small networks with acquaintances and friends. In doing so, they skirted the system of reputation, because they could not mediate crucial values, or simply because they privileged capital creation in other social fields. Importantly, these refugees identified, like merchants, with the urban middle class. Their mutual boundary-making was thus less tied to class identities than to a mismatch in the values the newcomers and the longstanding Iranian merchants applied to their work.

Consequently, established merchants were hardly able to control newcomer’s business strategies (see also Keshavarzian 2007, 152f.), if it was not through boundary-making and by strengthening their adherence to their own system of value. Instead of the German colleagues in the 1950s and 1960s, it was now the established Iranian merchants who blamed their bazar-outsider compatriots for unfair competition. A German documentary from 1989 shows M. Azadi—presented as an intellectual and a well-established merchant of antique Persian carpets—in front of a carpet discount shop, accusing its dumping prices of endangering reputable businesses (Helfer 1989). Pnina Werbner (1990, 66ff.), observes similar distinction of established migrant entrepreneurs from newer competitors through the discursive construction of moral and social superiority among traders of Pakistani origin in Manchester. Established merchants’ internal boundary-making thus served not only to protect their own system of value, but also to sustain their collective strategies of capital creation in Germany and in relations with the Iranian government.

Strikingly, the discussion shows that the system of value in the transnational social field of Iranian merchants remained relatively stable despite important political and economic changes. This stability may both be the reason and the outcome of its own resourcefulness: merchants drew on Iran-specific resources they had created in this social field to convey values, such as piety and selflessness, that had become relevant in the social field of Iranian foreign trade. Iran-specific resources also served to uphold and strengthen their effort to increase the value of exoticism and authenticity in the German context.

While hegemonic systems of value may indeed change quickly and dramatically, for instance through sudden political events, everyday politics of value of less powerful agents across local and transnational social fields may also influence value systems over extended time spans. Thus, modifications in systems of value rarely happen through exclusively hierarchical processes. Agents’ power derives from their—inherently unequal—potential for action (Graeber 2001, 259ff.). Value systems are thus produced by the interaction of agents pursuing malleable strategies of capital creation from unequal power positions.

Collectively Narrating Through the Crisis

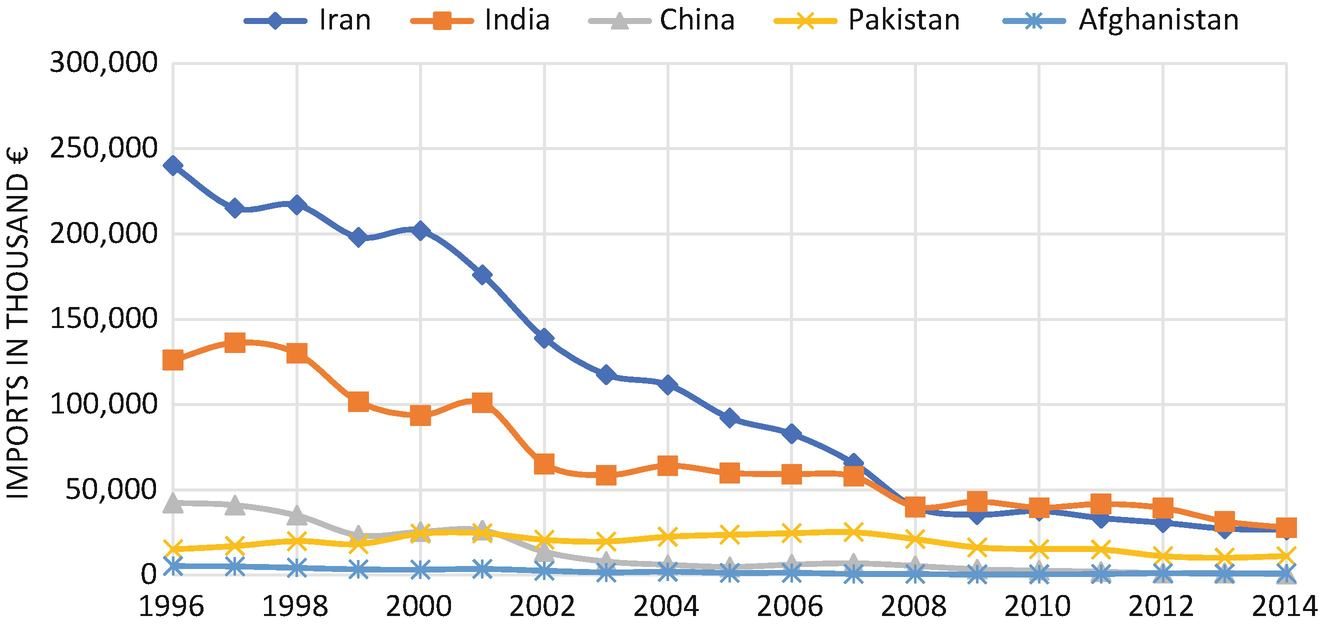

German import of hand-knotted carpets from selected countries between 1996 and 2014 (in thousand Euro, product codes: WA57011010, /90, /91, /93, /99, and WA57019010, /90). (data: Statistisches Bundesamt 2015, graphic by the author)

From the mid-1990s onward, the original values of the Iranian revolution that shaped the social field of Iranian foreign trade were complemented by values that responded to economic, political, and social changes. Iran’s classification as a member of the axis-of-evil in 2002, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s (2005–2013) fierce anti-Zionist discourses and the conflict over the Iranian nuclear program (Abrahamian 2008, 183ff.), finally the conclusion of the “Iran Deal” (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action) in 2015, then the USA’s withdrawal under the Trump administration in 2018: the Iranian economy is marked by recession and uncertainty. As economic and political pressures grow, trade relations with Europe and, in particular, with Germany become even more important—and carpets still are one of Iran’s largest non-oil export products (Statistical Centre of Iran 2014, 438). Private import-export enterprises, indeed, are crucial agents in circumventing trade restrictions and embargos (Gerhardt and Senyurt 2013). Significantly, in an interview from 2007, the Iranian deputy foreign minister for economic affairs at the time, Ali-Reza Sheikh-Attar, explains that one of the reasons for the “close understanding and direct contact between Iran and Germany in the economic field” is the “large Iranian community living in Germany” (Interview with the Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister for Economic Affairs Ali-Reza Sheikh-Attar 2007).

Today, the Iranian government continues to promote the revolutionary values of modesty, chastity, and piety. Simultaneously, its ever more neoliberal market economy, rising levels of education, the nuclearization of the family, and opaque, overlapping, and irregular economic structures (Keshavarzian 2007; Erami and Keshavarzian 2015), grant increasing value to wealth, autonomy, and professionalism (Kian-Thiébaut 2005; Sadjed 2012). Depending on the situation, resources that mediate familiarity with the German context may underline professionalism as they may be interpreted as a failure to convey regime-loyalty. The Iranian regime collaborates on a regular basis with Hamburg’s merchants, mainly through the association AICE16 (Rezaei 2009, 91), and through frequent visits of officials in Hamburg. In response to the introduction of new values, the government also created alliances outside of the merchant networks. Javid, a 69-year-old corporate consultant who immigrated to Germany as a young adult in the early 1980s, told me that it was the then-General Consul who proposed him to co-found the “Union of Iranian Entrepreneurs” (Bund Iranischer Unternehmer, shortly BIU) in 2007. The aim was to create an intermediary who could facilitate collaborations between the Iranian government and the Hamburg Senate.

Iran-related political events, but also the global economic crisis as well as local political and infrastructural changes complexified the system of value that dominates the social field of the German carpet market to a point that a resource may simultaneously mediate value and dramatically fail to do so.

Iran’s marginalization from the global political and economic exchanges impacts on the trade infrastructure,17 but, more importantly, on the meaning of Iran-specific resources. Plus, by the early 2000s, the German politics of immigration shifted from differentialism toward assimilation, which represents the requirement for migrants to mediate familiarity through cultural closeness (Aumüller 2009). We can see the effects of these developments in the following example: in 2010, the BIU created, together with the Iranian government and the Christian democratic Senate, the so-called Iran House Project (Iran-Haus Projekt). Javid, its president, told me that the aim was to show a “positive image” of Iran and foster business relations. However, the local population protested against the cooperation with Ahmadinejad’s government (Smechowski 2010), condemning the Iranian government for anti-Semitism and human rights violations.18 The oppositional SPD (Social Democratic Party of Germany) joined the movement (Dobusch 2010), which, according to Javid, accounts for the failure of the project—alongside inconstancies in the Iranian state financial support. The values of democracy, equality, and human rights are not always relevant in the carpet trade. Here, familiarity does not have to pass through cultural and racial closeness but can be created through long-term relations. Yet, these values are crucial in the social field of Hamburg’s domestic politics, as they are essential to European and Western political identity (Guilhot 2005; de Jong 2017). The fact that merchants’ mediation of exoticism and familiarity—central values in the social field of the German carpet market—was conditional to the compliance with democracy, equality, and human rights indicates that, in this example, two social fields overlap. Their systems of value are different, but unequally powerful. Thus, failing to convey democracy, equality, and human rights threatens to compromise Iranian merchants’ capital creation as it increases their difficulties to mediate both exoticism and familiarity.

The international economic crisis of the late 2000s also influenced the system of value in the German carpet market. Parviz and Rahim asserted that the taste of Northern Europeans and Americans shifted toward sober colors and plain designs, which they find in more economic Indian produces (see also Piehler 2009). Their comment suggests that instead of wealth, mediated through expensive and colorful Iranian carpets, customers value simplicity, plainness, and frugality.

He thus suggests, in a depreciative tone that stresses his own educational and professional resources, that a participation in the merchants’ system of reputation no longer guarantees business efficiency. Merchants indeed adapted their business strategies in various ways: Akbar and Rahim included cheaper Indian, Chinese, Pakistani, or Afghan carpets into their range of products and invested in new markets, like the Saudi Arabian market. Omid, who holds a Master in Business Administration, instead, sets forward a focus on Persian quality imports and antique carpets. They told me that other colleagues downsized their stocks, shifted to online sales, moved their premises to cheaper locations close to the airport, or switched to the retail or interior equipment business. Some moved on to the USA or elsewhere, or returned to Iran.It is not as if because of crisis less carpets are sold, and that all of a sudden people don’t want to have Persian carpets anymore. Instead, is [sic!] because of the crisis we heard much more negative things about Iran, than about the positive carpet. Until now, all people… How to say? Analphabets, came from Iran, had some money, about 100,000€. Then, they borrowed another 500, 400[,000€] from an Iranian, brought carpets in, imported them, and sold them. You did not need any expertise for this, nor did you need to do anything. But these times are over! (Interview, June 2014)

The marketing of Iranian culture is a way for Omid to mediate the failure to convey the values of democracy, equality, and human rights. “This is also why I say ‘Persian’ [i.e. instead of Iranian] carpets,” he told me. “What is identity good for if I can’t even pay the rent for my store?” (field notes, October 2013). Following a similar rationale, several press portraits of merchants characterize them as “politically impartial” (Spillmann 2003; Hertel 2011; Fründt 2014). Correspondingly, Omid’s large show room is decorated with Iranian cultural artifacts: a dummy with a colorful, embroidered vest and a huge book on a holder, probably by the poet Hafiz. When I first visited him, he told me that he awaited a group of people belonging to a German private club of which he is a member for an Iranian dinner. While staging cultural Iranianness is a popular way for people to redefine the values Iran-specific resources mediate (Sanadjian 2000; Mobasher 2006; Gholami 2015), in the case of carpet merchants, they have to fine-tune their politics of value so as to not impede on their capital creation in the social field of Iranian foreign trade.

I argued above that Iran-specific resources increasingly fail to create capital due to Iran’s image in the international political landscape. Yet, merchants have been coding Iran-specific resources to convey authenticity through exoticism since pre-revolutionary times, and from the 1980s, their efforts have shown positive results, sustained by the rising interest in authenticity in the larger society. In addition, through their long-term presence, they began to mediate familiarity despite cultural difference. The nostalgia of the “golden days” in which the image of Iran still reflected the attraction of the Oriental, yet, Western-orientated, wealthy and secular monarchy, through a selective “reordering of the past” (Guillaume 1990), is part of the merchants’ politics of redefining the value of Iran-specific resources.

Indeed, the restructuration managers declare wanting to preserve the carpet stock houses, which became a tourist attraction (Wolf 2005; Schmidt 2013). The nostalgia one can sense in this discourse is often combined with a romanticization of the carpet business, stressing the cultural alterity—the exoticism—and the historical continuity—the familiarity—of the merchants’ practices:Coffee, tea, and carpets – these are the “elements” which had marked the Speicherstadt for decades. One can still find the coffee sector, even though one must take a close look. The tea sector no longer marks the landscape behind the red brick houses, either. The carpet, however, survived visibly with its small-scale structures and great variety […]. The restructuration process is ongoing, the stocks dwindle. Will this wonderful piece of Orient remain with the Hanseatic city? (Hertel 2011)

Not only in discourse but also in practice, the long-term presence of Iranian merchants strengthens their mediation of familiarity. In a recent documentary (Schanzen and Keunecke 2018), the head of one of the oldest Iranian carpet merchant enterprises and the German manager of a transportation business state that ongoing collaboration over generations, which is facilitated through their neighborhood relations in the warehouse district, also helps to confront the defamiliarization of Iran-specific resources and the shift of values in the context of the economic crisis.The lorry that rolls through Hamburg’s Speicherstadt on this winter morning drove for eight days and took several thousand kilometers. Now it stops in front of a red clinkered stock house. A scuttle opens in the first floor. Warehousemen descend the rope on a simple winch and start heaving the precious cargo piece by piece to where it is warm and dry: 1650 hand-knotted carpets just arrived from Tehran. A scene from times long past. (Fründt 2014)

Thus, in the social field of the German carpet market, merchants create capital (and circumvent the failure to mediate democracy, equality, and human rights), on the one hand, through Iran-specific resources that refer to apparently apolitical commercial and personal practices and objects stressing family cohesion and tradition, as well as Germany-specific resources that reify Hamburg merchants’ historical ways of doing, convey authenticity and exoticism. On the other hand, Germany-specific resources that refer to their long local presence and business history mediate familiarity, expertise, and accountability. Strikingly, in this context, exoticism and familiarity are no longer mutually exclusive values, as they were during the pre-revolutionary years. However, the merchants’ capital creation remains particularly precarious as their politics contest dominant systems of value and the interpretation of their resources may hence be reversed at any time.

Finally, in the transnational social field of Iranian carpet merchants, the drive toward authenticity in German social fields, and the instauration of trade barriers in the Iranian context reinforced the existing system of value, as it strengthened the comparative advantages of those who were embedded in the merchants’ system of reputation. As Parviz mentioned in the conversation cited at the beginning of the previous section, the number of bankruptcies among wholesalers operating outside of long-term trust relations largely exceeded those among its members. This was because trade networks based on long-term relations built on mutual credit are highly interdependent: the insolvency of one member may affect the viability of other firms (Werbner 1990, 59–66). Moreover, family enterprises offer a workforce that more readily accepts flexible working conditions and salaries (Werbner 1990, 58f.; Jacques-Jouvenot and Droz 2015). In order to sustain collective business efficiency, merchants within the system of reputation have more flexible terms of payment, that is, credit, delayed payment or other forms of generalized exchange (Sahlins 1972, 196ff.), and better value for money. Outsiders to the network, instead, have to comply with the conditions of balanced exchange, that is, no delays or only short delays allowed for settling accounts, as they are considered untrustworthy (Keshavarzian 2007, 151f.). Significantly, a TV documentation from 2008 shows Omid as he buys a precious carpet at the Tehran bazar. He kisses the wholesaler on the cheek when the price is settled as a symbol of respect and long acquaintance. A German retailer asks the wholesaler how much the carpet would have costed if he had bought it instead. The merchant names a price exceeding by €1000 what Omid paid. The latter, in turn, comments: “He knows me for forty years. He knows you for forty minutes. That’s the problem” (Demurray 2008).

Yet, here too, the drive toward the segmentation of the post-revolutionary bazar and the professionalization of merchants outside of the traditional social networks introduced new values, which are apparent through the role of BIU and Javid in boundary work. I witnessed Omid and one of his merchant friends value Javid’s connections to German politicians, but also scoff his friendship with the Imam Ali mosque’s imam. His sister Oliya, a trained biologist in her mid-sixties with hair dyed in blond who speaks Persian and German to her two white terriers, volunteered as a treasurer at BIU for five years. She critiqued its high membership fees and low political impact, and Omid predicted that BIU is going to lose its influence. Yet, I could tell that my interlocutors withheld the whole extent of their accusations, which suggests that their system of reputation, in which inner conflicts are resolved out of sight from the public (Keshavarzian 2007), had come to include BIU and its members.

The valorization of internal social coherence and cooperation among merchants largely accounts for the success of their collective strategies of capital creation. I witnessed merchants visiting each other, or listened to them telling me they saw such and such at a wedding lately. Several interlocutors told me that the mosque for many remained an important setting for sociability. Merchants defer diverging identifications, religious beliefs, and moral and political convictions19 and maintain multiplex and crosscutting social relations, often over several decades and generations. Their reduced number further contributes to a greater cohesion and control (see also Erami and Keshavarzian 2015, 126). The high level of integration within this social field explains why it has not been necessary for Akbar to speak German fluently.

To resume, the Iranian carpet merchants’ collective identitary narrative promoting the resources such as Iranian identification, family cohesion, a long history in Hamburg, and (sometimes) also religious adherence caters to systems of value in three social fields. Strikingly, it largely draws on resources that were originally created through relations within their transnational social field. Here, they mediate the values of family coherence, accountability, selflessness, generosity, and piety (Keshavarzian 2007), which are crucial in their internal system of value since the early years of immigration to Hamburg. More recently, professionalism conveyed through good contacts to political and economic powerholders, as well as educational attainment became another important value. In the social field of Iranian foreign trade, these resources convey, besides piety, altruism, and family cohesion, also professionalism and wealth. In the German carpet market, in turn, they mediate authenticity and exoticism, but also familiarity, expertise, and accountability, while they may dissimulate their piety and their relations with the Iranian government. Thus, Iranian merchants’ collective politics within systems of value that change often unexpectedly and in unpredictable ways led to a convergence of their collective agency in the Iranian and German social fields of the carpet trade that promotes some of the same resources on which they build their internal cohesion.

The appropriation of the merchants’ narrative—in particular its two main pillars, Iranian origin and business continuity through kinship ties—by people who identify as Roma but are not of Iranian origin, underlines its efficiency in creating capital.Stay clear of these people! These gypsies lie! They always try to pass themselves off as Iranians. They say they are the nephews of such as such known carpet dealer and take the piss out of people. You should be very careful! (Field notes, October 2013)

The narrative is efficient, because it allows merchants to draw (in large part) on the same resources to create capital in the three social fields in which they are involved, although these are shaped by highly diverging systems of value. Indeed, due to changing local and transnational political, economic, and infrastructural conditions, and thanks to the merchants’ collective politics of value, their migration-specific resources that represent an Iranian identity building on ideas of tradition and family cohesion today mediate the respective values that enhance the creation of capital for business purposes in each of the professional social fields. Conversely, following the principles of diplomacy and complaisant submission—acts of impression management—merchants downplay resources that fail to promote crucial values in these social fields and thus threaten to create barriers to capital creation. These are, for instance, religious piety in the German carpet market and oppositional political engagements in the social field of Iranian foreign trade. Ultimately, the efficiency of politics of value relies on creating a maximum of capital from existing resources, while keeping the effort of generating new ones minimal.

The discussion of the way Iranian merchants engage with shifting systems of value in the local and transnational social fields of Iranian foreign trade, the German carpet market, and among their peer Iranian merchants throughout seven decades sheds light on the workings of systems of value. As agents’ power derives from their—inherently unequal—potential for action to determine the meaning of resources (Graeber 2001, 259ff.), I argued that value systems are produced by the interaction of agents pursuing malleable strategies of capital creation from unequal power positions. It became clear that both values and systems of value are ambiguous, ambivalent, contradictory, and, because they may shift at any time, transitional. Values do not stand for themselves. Their relations are shaped by interdependence, and, as some values occupy key positions respective to the mediation of other values, their strength and importance is unequal (cf. Dumont 2013; Hickel and Haynes 2018). Thus, for agents, mediating one value influences the mediation of others. The study of value in the context of capital creation shows that, just as values are ambiguous, so are resources: they can convey a single value or several values. They may as well convey a key value and simultaneously fail to mediate another crucial value. Barriers of capital creation come from unfulfilled crucial values.

As values are unequally important in one social field, so is the impact of barriers to capital creation unequal. The more central the value, the greater is the barrier to capital creation if it remains unfulfilled. Finally, I showed that dynamics in transnational social fields are highly interdependent and they mutually shape value systems. Systems of value interrelate when, as in the example to the Iran House project, social fields are overlapping, or when, as in the case of the values put forward by the Iranian monarchy, systems of value transgress the confines of a single social field. The potential for action of individual or collective agents lies thus in diplomatically crafting connections across systems of value through (sometimes arbitrary) value shifts with the help of fine-tuned politics of value in different social fields.

Karim, a 30-year-old barista of rather modest background, who came to Germany in 1986, told me that, among local Iranians, “the social status plays an important role. There are the upper classes: carpet merchants and intellectuals. They do not want to have anything to do with the others” (field notes, May 2013). Iranian merchants present a very particular case of collective capital creation, as their politics of value allow them to convey both familiarity and exoticism, that is, values that tend to be mutually exclusive in most social fields related to the German society. The next two chapters will show that post-revolutionary migrants who identify as “intellectuals” struggle with the opposition of these two values. The negotiation between different systems of value accounts for boundary-making between these two “groups” of Iranians.

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.