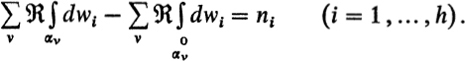

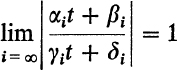

This may suffice to make the relation between the inversion problem and the theory of multiplicative functions and differentials clear. Abel himself proved only that part of the theorem above named for him which states that if ![]() are the zeros and

are the zeros and ![]() are the poles of a meromorphic function, then the congruences (18.2) hold. But he proved this part in a sharper form, with congruence modulo G0 replaced by congruence modulo G.26 Thus with the inversion already proved, one obtains the following.

are the poles of a meromorphic function, then the congruences (18.2) hold. But he proved this part in a sharper form, with congruence modulo G0 replaced by congruence modulo G.26 Thus with the inversion already proved, one obtains the following.

Abel’s Theorem (second version). The points ![]() ;

;![]() are the sets of zeros and poles, respectively, of a meromorphic function if and only if, for a suitable choice (independent of w) of the paths from

are the sets of zeros and poles, respectively, of a meromorphic function if and only if, for a suitable choice (independent of w) of the paths from ![]() to the points

to the points ![]() and

and ![]() , every Abelian integral w of the first kind satisfies the equation

, every Abelian integral w of the first kind satisfies the equation

Let z be any nonconstant meromorphic function on ![]() . It assumes, as we know, every value the same number of times, say n times. Then the surface

. It assumes, as we know, every value the same number of times, say n times. Then the surface ![]() may be regarded as an n-sheeted covering surface

may be regarded as an n-sheeted covering surface ![]() over the z-sphere, if one agrees that a point

over the z-sphere, if one agrees that a point ![]() of

of ![]() lies over the point z = a of the z-sphere if the function z has the value a at

lies over the point z = a of the z-sphere if the function z has the value a at ![]() . This is the conception of a Riemann surface which Riemann himself employed in his works on algebraic functions and their integrals, and one would say today that Abel’s argument is most easily understood from this representation. Over those values a, for which the n points

. This is the conception of a Riemann surface which Riemann himself employed in his works on algebraic functions and their integrals, and one would say today that Abel’s argument is most easily understood from this representation. Over those values a, for which the n points ![]() at which z assumes the value a are not all distinct, there are certainly fewer than n points of the covering surface. If the function z assumes the finite value a r times at the point

at which z assumes the value a are not all distinct, there are certainly fewer than n points of the covering surface. If the function z assumes the finite value a r times at the point ![]() , then

, then ![]() is a local parameter at

is a local parameter at ![]() ; the point

; the point ![]() over a is a branch point of order r − 1. If

over a is a branch point of order r − 1. If ![]() is any neighborhood of

is any neighborhood of ![]() , then there exists a disc

, then there exists a disc ![]() on the z-sphere such that over every point of this disc (except the center) there are exactly r points of

on the z-sphere such that over every point of this disc (except the center) there are exactly r points of ![]() which lie in the neighborhood

which lie in the neighborhood ![]() . dz has a zero of order r − 1 at

. dz has a zero of order r − 1 at ![]() . (Therefore there can be only finitely many such values z = a over which there are fewer than n points of

. (Therefore there can be only finitely many such values z = a over which there are fewer than n points of ![]() .) If z assumes the value ∞ s times at the point

.) If z assumes the value ∞ s times at the point ![]() , then

, then ![]() is a local parameter at

is a local parameter at ![]() and we have a branch point of order s − 1; dz has a pole of order s + 1 at

and we have a branch point of order s − 1; dz has a pole of order s + 1 at ![]() . We denote the sum of the orders of all the branch points of the surface, its “branch order” by V. Then: the number of zeros − the number of poles of

. We denote the sum of the orders of all the branch points of the surface, its “branch order” by V. Then: the number of zeros − the number of poles of ![]() where the first sum on the right is over all points of the surface except those over z = ∞, while the second sum is over precisely the points over z = ∞. The right-hand side of this equation is

where the first sum on the right is over all points of the surface except those over z = ∞, while the second sum is over precisely the points over z = ∞. The right-hand side of this equation is

![]()

and the left-hand side = 2p − 2. Hence

![]()

The branch order is always even.

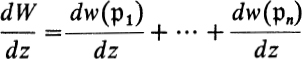

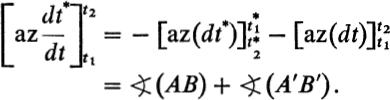

Now let dw be an arbitrary differential of the first kind on ![]() and let

and let ![]() in general be the points of

in general be the points of ![]() over the point z on the z-sphere. Then

over the point z on the z-sphere. Then

is a differential dW, which is regular everywhere on the z-sphere. But such a differential does not exist, except for dW = 0. If we draw any curve on the z-sphere from the south pole z = 0 to the north pole z = ∞, then the points of ![]() over this curve (which sometimes coalesce at branch points) form curves γ1, …, γn and it follows from integrating dW that

over this curve (which sometimes coalesce at branch points) form curves γ1, …, γn and it follows from integrating dW that

![]()

Each curve yv leads from a zero ![]() to a pole

to a pole ![]() of z. If one joins

of z. If one joins ![]() to

to ![]() by a curve

by a curve ![]() and denotes the curve

and denotes the curve ![]() then we obtain, as claimed, the equation (18.6).

then we obtain, as claimed, the equation (18.6).

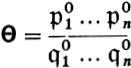

Conversely, the congruences (18.2) follow from these equations, and hence the fact that the multiplicative function

has the multipliers ![]() = 1 and is uniform on

= 1 and is uniform on ![]() .

.

The coincidence of the lattices G and G0 now comes out as follows. First, by the lemma there exist points ![]() such that

such that

provided that the ni are given integers. In this process, definite paths ![]() and

and ![]() have been chosen. From this it follows that the multiplicative function

have been chosen. From this it follows that the multiplicative function

is uniform on ![]() . Hence, by the proof just carried out, paths

. Hence, by the proof just carried out, paths ![]() and

and ![]() may be determined so that for these paths the left-hand sides of (18.7) all vanish. Now

may be determined so that for these paths the left-hand sides of (18.7) all vanish. Now ![]() and

and ![]() are closed paths for which

are closed paths for which

The 2N closed loops ![]() and αv give together a closed path

and αv give together a closed path ![]() whose intersection numbers

whose intersection numbers ![]() with the curves αi of the integral basis, are the given integers ni.

with the curves αi of the integral basis, are the given integers ni.

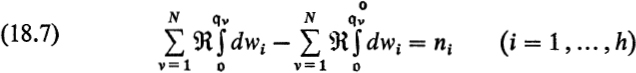

Analytically one attacks the Jacobi inversion problem as follows. One uses an arbitrary meromorphic function f(![]() ) on

) on ![]() and attempts to determine, not the points

and attempts to determine, not the points ![]() themselves, but the values of the function f at the points

themselves, but the values of the function f at the points ![]() from (18.3) in their dependence on F1, F2, …, Fp. Since the values

from (18.3) in their dependence on F1, F2, …, Fp. Since the values ![]() are determined only to within a permutation, it makes better sense to replace them by their elementary symmetric functions; that is, by the coefficients of the equation

are determined only to within a permutation, it makes better sense to replace them by their elementary symmetric functions; that is, by the coefficients of the equation

![]()

of degree p whose roots are the numbers

![]()

These coefficients Ai, expressed in terms of ![]() are called, following Jacobi’s proposal, Abelian functions. Except for the singular systems

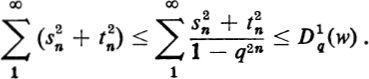

are called, following Jacobi’s proposal, Abelian functions. Except for the singular systems ![]() which form a subspace of dimension only (2p − 4) in the whole 2p-dimensional F-space, the Abelian functions are uniform and regular analytic. Furthermore, they are 2p-fold periodic. For if γI (l = 1, 2, …, 2p) is an integral basis for the closed paths on

which form a subspace of dimension only (2p − 4) in the whole 2p-dimensional F-space, the Abelian functions are uniform and regular analytic. Furthermore, they are 2p-fold periodic. For if γI (l = 1, 2, …, 2p) is an integral basis for the closed paths on ![]() and if

and if

![]()

then, for every value of the index l, the numbers ![]() are a period system for the Abelian function A((F)):

are a period system for the Abelian function A((F)):

![]()

These 2p period systems are linearly independent in the following sense: the determinant whose lth row is

![]()

is nonzero. If one carries through explicitly the proof which has been given here of the solvability of the inversion problem, then one obtains the following result: in every bounded portion

![]()

of the F-space, an Abelian function A((F)) may be represented as the quotient of two functions which are regular analytic throughout this bounded portion.27 The indeterminateness for the singular systems (F) arises because for these values both the numerator and the denominator in the representation vanish. The set of the points of indeterminateness possesses no translations onto itself except for those which obviously come from the periodicity of the Abelian functions.

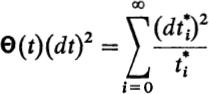

Furthermore, Riemann and Weierstrass showed, by a much more penetrating analysis, that the Abelian functions, without restriction to a bounded set, may be represented as quotients of transcendental entire functions, the θ-functions. They gave an explicit analytic expression in the form of a rapidly convergent infinite series for the θ-functions. These 0-functions also suffice as a basis for the general theory of the 2p-fold periodic functions of p independent complex arguments; the theory of Abelian functions is only a special case.28

The contents of this and the preceding paragraph show convincingly the ruling role played by the genus p, which is in essence a topological quantity, in the theory of functions and integrals on a closed Riemann surface. We were concerned with two trains of thought which we shall state once again with the labels

additive functions, partial fraction decomposition, Riemann-Roch theorem multiplicative functions, product representation, Abel’s theorem.

These two trains of thought permeate the theory of uniform functions on ![]() from here on this theory is easily completed with the aid of the reciprocity laws of § 16. But the significance of this structure shows up in the proper light only when we become familiar with the system of meromorphic functions on a closed Riemann surface from a third point of view, as an algebraic function field; this will be done in the next section. And first from this aspect do those functions appear most intimately related to our other interests, the algebraic and the geometric - in so far as these relate to the theory of algebraic curves in the plane and in spaces of higher dimension.

from here on this theory is easily completed with the aid of the reciprocity laws of § 16. But the significance of this structure shows up in the proper light only when we become familiar with the system of meromorphic functions on a closed Riemann surface from a third point of view, as an algebraic function field; this will be done in the next section. And first from this aspect do those functions appear most intimately related to our other interests, the algebraic and the geometric - in so far as these relate to the theory of algebraic curves in the plane and in spaces of higher dimension.

§ 19. The algebraic function field

The meromorphic functions on a given closed Riemann surface ![]() form a field; this means precisely that the sum, difference, product, and quotient of two meromorphic functions (only division by 0 is ruled out) is again such a function. As was already done in the last section, one chooses a definite nonconstant meromorphic function z on

form a field; this means precisely that the sum, difference, product, and quotient of two meromorphic functions (only division by 0 is ruled out) is again such a function. As was already done in the last section, one chooses a definite nonconstant meromorphic function z on ![]() for the independent variable. Thereby

for the independent variable. Thereby ![]() becomes an n-sheeted covering surface

becomes an n-sheeted covering surface ![]() over the z-sphere, and the uniform meromorphic functions f on

over the z-sphere, and the uniform meromorphic functions f on ![]() become n-valued algebraic functions of z. In this fashion there exists an algebraic function field belonging to

become n-valued algebraic functions of z. In this fashion there exists an algebraic function field belonging to ![]() , which includes the field k(z) = k of rational functions of z. Namely, the meromorphic function f satisfies identically a definite equation

, which includes the field k(z) = k of rational functions of z. Namely, the meromorphic function f satisfies identically a definite equation

![]()

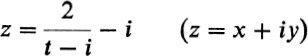

of degree n, in which the ri(z) are rational functions of z. More precisely, this means the following. Let ![]() be any point of

be any point of ![]() , let t be a local parameter at

, let t be a local parameter at ![]() , and let z = z(t) and f = f(t) be the expansions of z and f in integral powers of t in the neighborhood of

, and let z = z(t) and f = f(t) be the expansions of z and f in integral powers of t in the neighborhood of ![]() ; then the left-hand side of (19.1) becomes identically zero when one substitutes the power series z(t) and f(t) for z and f respectively. To derive the equation (19.1), we first exclude the point z = ∞ from the z-sphere as well as those points over which there are branch points, and those points over which f has poles. For every other value of z we form the number

; then the left-hand side of (19.1) becomes identically zero when one substitutes the power series z(t) and f(t) for z and f respectively. To derive the equation (19.1), we first exclude the point z = ∞ from the z-sphere as well as those points over which there are branch points, and those points over which f has poles. For every other value of z we form the number

![]()

where the sum on the right is over the n points over z. The sum is independent of the ordering of these points. In the neighborhood of a nonexcluded point

![]()

![]() become power series in z − z0, and r1(z) is a regular analytic function at every nonexcluded point. This function cannot have an essential singularity at any excluded point; hence it has only poles. If one uses a local parameter at a point of

become power series in z − z0, and r1(z) is a regular analytic function at every nonexcluded point. This function cannot have an essential singularity at any excluded point; hence it has only poles. If one uses a local parameter at a point of ![]() z over an excluded value z0, this may also be verified by elementary calculation. Hence r1(z) is a rational function of z. Similarly, one sees that the other elementary symmetric functions of

z over an excluded value z0, this may also be verified by elementary calculation. Hence r1(z) is a rational function of z. Similarly, one sees that the other elementary symmetric functions of ![]() are rational functions of z. The equation (19.1), which is determined uniquely by f is called the field equation of f.

are rational functions of z. The equation (19.1), which is determined uniquely by f is called the field equation of f.

Furthermore, I claim that from the functions g belonging to the function field K associated with ![]() z, an f may he chosen such that every g may be expressed rationally in terms of f and z. This f is called a function determining the function field. If

z, an f may he chosen such that every g may be expressed rationally in terms of f and z. This f is called a function determining the function field. If ![]() z, has the n distinct points

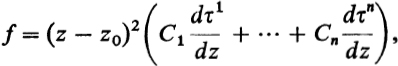

z, has the n distinct points ![]() over z0, then it suffices to choose f such that it assumes n distinct values at these points. If dτk (k = 1, …, n) is a differential that has a pole only at

over z0, then it suffices to choose f such that it assumes n distinct values at these points. If dτk (k = 1, …, n) is a differential that has a pole only at ![]() and has the principal part − (z − z0)−2dz, then one can set, for example,

and has the principal part − (z − z0)−2dz, then one can set, for example,

where one chooses any n different constants for C1, …, Cn. The field equation of f is then irreducible; that is, its left-hand side, the polynomial

![]()

of degree n in the variable u, cannot be factored into two polynomials ![]() whose coefficients are also rational functions of z. For assume that this were possible; in a neighborhood of

whose coefficients are also rational functions of z. For assume that this were possible; in a neighborhood of ![]() , f may be developed in a power series in the local parameter z − z0 at

, f may be developed in a power series in the local parameter z − z0 at ![]() . Suppose that this power series, replacing u, satisfies the equation

. Suppose that this power series, replacing u, satisfies the equation ![]() . Join

. Join ![]() to any one of the points

to any one of the points ![]() by a curve on

by a curve on ![]() whose trace on the z-sphere does not pass through any of the excluded points. Then all the function elements (z,f) along this curve must satisfy the equation

whose trace on the z-sphere does not pass through any of the excluded points. Then all the function elements (z,f) along this curve must satisfy the equation ![]() . Hence f(

. Hence f(![]() ) is also a root of the equation

) is also a root of the equation ![]() thus it has n distinct roots and must be of degree n. Hence

thus it has n distinct roots and must be of degree n. Hence ![]() is only of degree 0 in u, and a factorization of the contemplated type does not exist.

is only of degree 0 in u, and a factorization of the contemplated type does not exist.

To each point ![]() of

of ![]() there belongs a function element (z, f) which satisfies the equation Fz(u) = 0. For two distinct points these function elements are always different, and the elements belonging to all points

there belongs a function element (z, f) which satisfies the equation Fz(u) = 0. For two distinct points these function elements are always different, and the elements belonging to all points ![]() exhaust the totality of those which satisfy that equation. In other words: the totality of those function elements which satisfy the irreducible algebraic equation Fz (u) = 0 constitutes a single analytic form in the sense of Weierstrass. This analytic form, regarded as a Riemann surface, is conformally equivalent to the given Riemann surface. The given surface is- the Riemann surface which belongs to the algebraic form defined by the equation Fz(u) = 0.

exhaust the totality of those which satisfy that equation. In other words: the totality of those function elements which satisfy the irreducible algebraic equation Fz (u) = 0 constitutes a single analytic form in the sense of Weierstrass. This analytic form, regarded as a Riemann surface, is conformally equivalent to the given Riemann surface. The given surface is- the Riemann surface which belongs to the algebraic form defined by the equation Fz(u) = 0.

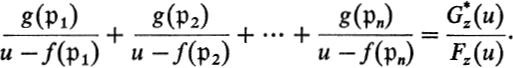

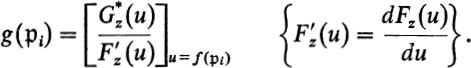

In order to express the given element g of the function field K rationally in f, we apply the Lagrange interpolation formula

Again ![]() denote the n points of

denote the n points of ![]() over the point z on the z-sphere. By the same argument as above, one finds that the coefficients of the polynomial

over the point z on the z-sphere. By the same argument as above, one finds that the coefficients of the polynomial ![]() of degree n − 1, are rational functions of z. For all values of z for which

of degree n − 1, are rational functions of z. For all values of z for which ![]() are different, it follows that

are different, it follows that

Since the polynomial Fz(u) is irreducible over the coefficient field k(z), Fz(u) and ![]() are without common divisor over this field. Therefore the Euclidean division algorithm produces two polynomials, Hz(u) and Lz(u), with coefficients which are rational functions of z, such that

are without common divisor over this field. Therefore the Euclidean division algorithm produces two polynomials, Hz(u) and Lz(u), with coefficients which are rational functions of z, such that

![]()

If we introduce the polynomial ![]() , then the equation

, then the equation

![]()

becomes an identity on the surface. Finally, by means of the equation Fz(u) = 0, the polynomial Gz(u) may be reduced to one of degree n − 1. Hence any element g of our function field has a unique representation of the form

![]()

where the Ri(z) are rational functions of z. In this sense the quantities 1, f, …, fn−1 form a basis for the algebraic function field K relative to the ground field k of rational functions of z. Hence one calls n the degree of K over k.

Here one finds a purely algebraic attack on the idea of a function field. One operates with polynomials G(u) with coefficients in the field k. An irreducible polynomial F(u) of degree n is given. By identifying polynomials G(u) which are congruent modulo F(u), the “ring” of polynomials becomes a field K, of degree n over the ground field k,29

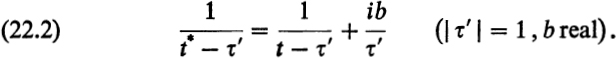

If the independent variable z is replaced by any other function, z*, on the surface, then there are infinitely many ways of choosing the function f* on the surface such that all functions may be expressed rationally in terms of z and f*. There is an irreducible algebraic equation F*z*(f*) = 0 relating z* and f*. Also, z* and f* are rational functions of the variables z and f, which are related by Fz(f) = 0; conversely, z and f are rational functions of the variables z* and f*, which are related by F*z*(f*) = 0. Through the birational transformation (z,f) ![]() (z*, f*) the equations

(z*, f*) the equations

![]()

turn into each other. The degree of this equation is, naturally, not by any means an invariant under birational transformations. But the genus p is invariant under birational transformations.

If there exists a function z on ![]() which takes each value just once, then the associated algebraic function field is the field of rational functions of z (and p = 0). If there is no function on

which takes each value just once, then the associated algebraic function field is the field of rational functions of z (and p = 0). If there is no function on ![]() which takes each value just once, but if there is a function z which takes each value exactly twice, then we may assume that the algebraic equation (which must be quadratic) determining the function field has the form

which takes each value just once, but if there is a function z which takes each value exactly twice, then we may assume that the algebraic equation (which must be quadratic) determining the function field has the form

![]()

where the ei are all different. These l points and, if l is odd, the point ∞, are branch points of order 1, and hence the genus p is = (l/2) − 1 if l is even, and = (l − 1)/2 if l is odd. We see that l = 1 or 2 leads again to the rational field p = 0; l = 3 or l = 4 gives p = 1, which is the elliptic case; if l > 4, we get the so-called hyperelliptic function fields.

In an arbitrary algebraic function field of genus p = 1 there always exists a function with two prescribed poles, therefore a function which assumes each value only twice. In every function field of genus 2 we obtain a function of the same sort by dividing two linearly independent Abelian differentials of the first kind. But, starting with p = 3, the hyperelliptic case is no longer the general one.

In the theory of algebraic function fields, two paths are clearly indicated along which one can reach a deeper understanding of the laws governing them. One is that of abstract algebra; here the algebraic concepts of field, field extensions, the degree of a field over the ground field, the degree of transcendence, prime place, etc., are paramount; one admits coefficient fields of characteristic other than zero. Here algebraic construction must furnish that which was accomplished in our development by the Dirichlet principle and the method of integration. The other path, that trod by Riemann, is the “topological,” which we have followed. One may describe Weierstrass’ point of view as an algebraic-function-theoretic one lying between these two extremes: explicit construction reigns, but one always operates in the continuum of complex numbers. Similar remarks apply to the “Kurventheoretiker” of the German and Italian schools. The concept of an analytic form as a two-dimensional manifold lies close enough here, even if the further step, of regarding the topological properties of this manifold as more primitive than all others, is not completed. Furthermore, it is characteristic of the Riemannian type of development that it is always the Riemann surface, not the analytic form, which is regarded as the given object; the construction of an associated analytic form is a principal component of the problem to be solved. To be sure, in Riemann’s treatment itself this point of view does not appear with the complete clarity with which we can now distill it from the works of Prym, Dedekind,30 C. Neumann, and particularly Klein.31

Every closed Riemann surface of genus p may, as we saw, be represented as a multiple-sheeted covering surface over the sphere (with finitely many branch points, and without boundary). There is a great multitude of these “normal forms,” even when one normalizes the number of sheets by the condition n = p + 1 (which is always possible). A much more fundamental significance attaches to the essentially unique normal form of the Riemann surface of arbitrary genus, which is furnished by the theory of uniformization (theory of automorphic functions).

In the theory of uniformization the ideas of Weierstrass and of Riemann grow into a complete unity. With Weierstrass the analytic form (z, u) is described at each individual point by a particular representation with the aid of a parameter t (the “local parameters”): z = z(t), u = u(t). Certainly Riemann obtains a global representation z = z(![]() ), u = u(

), u = u(![]() ) of the whole form, but he is forced to regard the parameter

) of the whole form, but he is forced to regard the parameter ![]() as a point on a Riemann surface (not as a complex variable in the usual sense). Uniformization theory is concerned with obtaining a global representation z = z(t), u = u(t) with the aid of a parameter t, the uniformizing variable, which varies in a domain of the smooth complex plane. F. Klein and H. Poincaré32 must be named as the true founders of the theory of automorphic functions, to which our problem leads. Their way to the general concepts and results was prepared in the literature by important, but more specialized, investigations of Riemann, Schwarz, Fuchs, Dedekind, Klein, and Schottky. The proof of the possibility of uniformization, based on the concept of a covering surface, was furnished simultaneously in 1907 by P. Koebe and H. Poincaré.33 From then on, Koebe spent his whole scientific life in studying the problem of uniformization thoroughly from all sides, and with the most varied methods.34 To him above all we owe it that today the theory of uniformization, which certainly may claim a central role in complex function theory, stands before us as a mathematical structure of particular harmony and grandeur.

as a point on a Riemann surface (not as a complex variable in the usual sense). Uniformization theory is concerned with obtaining a global representation z = z(t), u = u(t) with the aid of a parameter t, the uniformizing variable, which varies in a domain of the smooth complex plane. F. Klein and H. Poincaré32 must be named as the true founders of the theory of automorphic functions, to which our problem leads. Their way to the general concepts and results was prepared in the literature by important, but more specialized, investigations of Riemann, Schwarz, Fuchs, Dedekind, Klein, and Schottky. The proof of the possibility of uniformization, based on the concept of a covering surface, was furnished simultaneously in 1907 by P. Koebe and H. Poincaré.33 From then on, Koebe spent his whole scientific life in studying the problem of uniformization thoroughly from all sides, and with the most varied methods.34 To him above all we owe it that today the theory of uniformization, which certainly may claim a central role in complex function theory, stands before us as a mathematical structure of particular harmony and grandeur.

The basic idea of the following proof, to derive the existence of the uniformizing variable from the Dirichlet principle, comes from Hilbert.35

The uniformizing variable t that we seek should be such that it is suitable as a local parameter at each point of the given surface ![]() . Therefore it must be a uniform function, regular analytic except for poles of order one, on the universal covering surface

. Therefore it must be a uniform function, regular analytic except for poles of order one, on the universal covering surface ![]() . If we seek that function t which possesses the strongest uniformizing power, then we will attempt to determine t such that it assumes distinct values at any two distinct points of the surface

. If we seek that function t which possesses the strongest uniformizing power, then we will attempt to determine t such that it assumes distinct values at any two distinct points of the surface ![]() ; then it will map

; then it will map ![]() one-to-one and conformally onto a domain of the t-sphere. Then not only the functions on the base surface

one-to-one and conformally onto a domain of the t-sphere. Then not only the functions on the base surface ![]() can be represented as uniform functions of t; but also the much larger class of functions (which are in general infinitely many-valued on

can be represented as uniform functions of t; but also the much larger class of functions (which are in general infinitely many-valued on ![]() ) which arise from any function element on

) which arise from any function element on ![]() which can be continued, without branching, along all paths in

which can be continued, without branching, along all paths in ![]() . And since

. And since ![]() (in contrast to

(in contrast to ![]() ) is simply connected, the possibility of such a map does not contradict the analysis-situs properties of

) is simply connected, the possibility of such a map does not contradict the analysis-situs properties of ![]() . We may well drop now the basic assumption of the preceding sections, that

. We may well drop now the basic assumption of the preceding sections, that ![]() be closed; this assumption would not simplify anything in uniformization theory.

be closed; this assumption would not simplify anything in uniformization theory.

We obtain the desired uniformizing variable simply by applying the Dirichlet principle, not to ![]() , but to the universal covering surface

, but to the universal covering surface ![]() . We choose a point

. We choose a point ![]() on

on ![]() with the local parameter ζ; then we construct on

with the local parameter ζ; then we construct on ![]() , with the aid of the Dirichlet principle, the potential function U which is regular everywhere on

, with the aid of the Dirichlet principle, the potential function U which is regular everywhere on ![]() except at

except at ![]() , which behaves like

, which behaves like ![]() (1/ζ) at

(1/ζ) at ![]() , and with the following properties.

, and with the following properties.

(1) The Dirichlet integral of U over all of ![]() , except for an arbitrarily small ζ-disc about

, except for an arbitrarily small ζ-disc about ![]() , is finite,

, is finite,

(2) For every continuously differentiable function w on ![]() , with finite Dirichlet integral, which vanishes in a neighborhood of

, with finite Dirichlet integral, which vanishes in a neighborhood of ![]() , the variation D(U, w) satisfies

, the variation D(U, w) satisfies

![]()

U generates a differential dτ on ![]() ; since

; since ![]() is simply connected, this must be the differential of a certain function

is simply connected, this must be the differential of a certain function

![]()

whose real part coincides with U, which is regular analytic everywhere except at ![]() , and which has a pole of order one at

, and which has a pole of order one at ![]() . Then τ is a uniformizing variable of the type we seek. The proof of this fact follows in a very elegant fashion with the aid of the following deduction, due to Koebe.36

. Then τ is a uniformizing variable of the type we seek. The proof of this fact follows in a very elegant fashion with the aid of the following deduction, due to Koebe.36

We prove first the following fact.

If V0 is any real constant, then the points of ![]() at which V > V0 form a single domain; similarly for the points where V < V0.

at which V > V0 form a single domain; similarly for the points where V < V0.

Now 1/τ is a local parameter at ![]() ; let K0 : | 1/τ | ≤ a0, be a (l/τ)-disc about

; let K0 : | 1/τ | ≤ a0, be a (l/τ)-disc about ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() (V0) be the closed set on

(V0) be the closed set on ![]() consistingofthepoints where V = V0; then certainly only two of the domains determined by

consistingofthepoints where V = V0; then certainly only two of the domains determined by ![]() (V0) have points in K0. If our claim were false, then among the domains determined by

(V0) have points in K0. If our claim were false, then among the domains determined by ![]() (V0) there would be one, say

(V0) there would be one, say ![]() , that did not penetrate the neighborhood K0 of

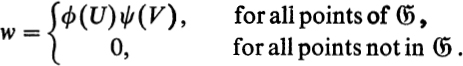

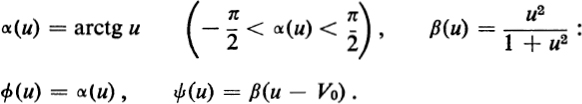

, that did not penetrate the neighborhood K0 of ![]() . Now let ϕ(u) and ψ(u) be any two real functions, defined and continuously differentiable for all real values u. We form the following function w on the surface

. Now let ϕ(u) and ψ(u) be any two real functions, defined and continuously differentiable for all real values u. We form the following function w on the surface ![]() :

:

This function is everywhere continuously differentiable, provided that

In the neighborhood K0 of ![]() , w vanishes identically. If

, w vanishes identically. If ![]() is any point in

is any point in ![]() and if z = x + iy is a local parameter at

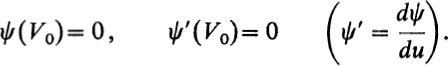

and if z = x + iy is a local parameter at ![]() , then

, then

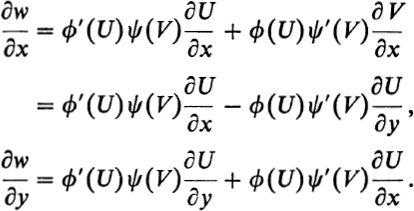

If ϕ, ϕ′, ψ, and ψ′ are bounded functions, then the Dirichlet integral of w over all of ![]() will be finite. Then, under the given conditions, D(U, w) = 0. Now

will be finite. Then, under the given conditions, D(U, w) = 0. Now

If we choose ϕ and ψ such that and ϕ′ and ψ are positive for all values of their argument (except for u = V0 in the case of ψ), then we have a contradiction.37

From the fact proved, and the simple connectivity of ![]() , one can draw conclusions on the behavior of τ.

, one can draw conclusions on the behavior of τ.

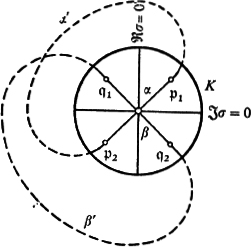

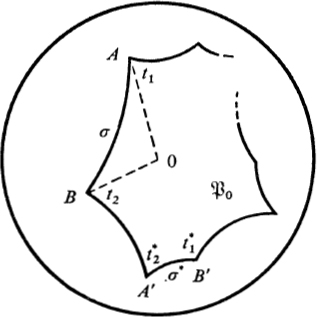

(1) dτ has no zeros. If at a point ![]() on

on ![]() , where τ = τ0, dτ = 0, then not τ − τ0, but (τ − τ0)1/r (r an integer ≥ 2) would be a local parameter at

, where τ = τ0, dτ = 0, then not τ − τ0, but (τ − τ0)1/r (r an integer ≥ 2) would be a local parameter at ![]() ; let us assume r = 2; the proof for larger r is analogous. I set τ − τ0 = σ2 and draw in the complex σ-plane a disc K, with center σ = 0, so small that it is, via the function σ, the conformal image of a certain neighborhood of the point

; let us assume r = 2; the proof for larger r is analogous. I set τ − τ0 = σ2 and draw in the complex σ-plane a disc K, with center σ = 0, so small that it is, via the function σ, the conformal image of a certain neighborhood of the point ![]() on

on ![]() . I take four points

. I take four points ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() in K, as indicated in Fig. 9, which are the vertices of a cross formed by two linear segments, α and β, crossing at the origin. At

in K, as indicated in Fig. 9, which are the vertices of a cross formed by two linear segments, α and β, crossing at the origin. At ![]() and

and ![]() , V > V0; at

, V > V0; at ![]() and

and ![]() , V < V0. I think of this figure transferred to the surface

, V < V0. I think of this figure transferred to the surface ![]() ; then I can join

; then I can join ![]() and

and ![]() by a curve α′, at every point of which V > V0; likewise, I can join

by a curve α′, at every point of which V > V0; likewise, I can join ![]() and

and ![]() by a curve β′ on which V < V0. The intersection number of the two closed curves, α + α′ and β + β′, is thus = 1. But this contradicts the fact that α + α′, as a curve on the simply connected surface

by a curve β′ on which V < V0. The intersection number of the two closed curves, α + α′ and β + β′, is thus = 1. But this contradicts the fact that α + α′, as a curve on the simply connected surface ![]() , must be homologous to zero.

, must be homologous to zero.

FIGURE 9

(2) If I say that a point of the surface ![]() , at which τ has the value τ0, lies over the point τ0 of the τ-sphere, then

, at which τ has the value τ0, lies over the point τ0 of the τ-sphere, then ![]() becomes a covering surface

becomes a covering surface ![]() of the τ-sphere or the τ-plane. By what we have proved under (1), this covering is unbranched. There is just one point,

of the τ-sphere or the τ-plane. By what we have proved under (1), this covering is unbranched. There is just one point, ![]() , over τ = ∞. I follow the line V = V0, starting at τ = ∞, in the τ-plane in the direction from smaller to larger values of U; on

, over τ = ∞. I follow the line V = V0, starting at τ = ∞, in the τ-plane in the direction from smaller to larger values of U; on ![]() , the point

, the point ![]() , starting at

, starting at ![]() , traces a curve over this line in the τ-plane. If I do not run into any boundary before returning to ∞, then

, traces a curve over this line in the τ-plane. If I do not run into any boundary before returning to ∞, then ![]() describes a closed curve

describes a closed curve ![]() , for there is only the single point

, for there is only the single point ![]() over ∞ then

over ∞ then ![]() covers the line V = V0 in the τ-plane simply. But if I meet an obstruction, then I obtain a curve

covers the line V = V0 in the τ-plane simply. But if I meet an obstruction, then I obtain a curve ![]() on

on ![]() which covers a certain piece U < U1 of the line V = V0 simply. Then I follow the line V = V0, now from larger to smaller values of U, and obtain a curve

which covers a certain piece U < U1 of the line V = V0 simply. Then I follow the line V = V0, now from larger to smaller values of U, and obtain a curve ![]() on

on ![]() which covers a piece U > U2 of the line simply. The sum

which covers a piece U > U2 of the line simply. The sum ![]() +

+ ![]() forms a curve

forms a curve ![]() through

through ![]() , nonclosed, and without end on

, nonclosed, and without end on ![]() . In either case, the curve

. In either case, the curve ![]() separates the surface

separates the surface ![]() , since it is simply connected, into two domains,

, since it is simply connected, into two domains, ![]() and

and ![]() . If, outside of

. If, outside of ![]() , there were points of

, there were points of ![]() at which V = V0, say in

at which V = V0, say in ![]() , then there would be points in

, then there would be points in ![]() at which V < V0 and points at which V > V0. The point set

at which V < V0 and points at which V > V0. The point set ![]() (V0) would then determine at least three domains. Therefore

(V0) would then determine at least three domains. Therefore ![]() exhausts the points at which V = V0. Thus, as a covering of the τ-sphere,

exhausts the points at which V = V0. Thus, as a covering of the τ-sphere, ![]() is everywhere at most two sheeted. A value U0 + iV0 will certainly occur once and only once on

is everywhere at most two sheeted. A value U0 + iV0 will certainly occur once and only once on ![]() , if V = V0 is a closed curve on

, if V = V0 is a closed curve on ![]() .

.

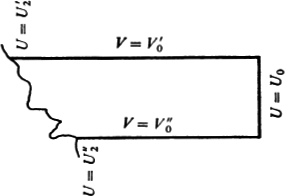

FIGURE 10

We still want to prove carefully that ![]() must always separate the surface

must always separate the surface ![]() . For this purpose we construct a two-sheeted, unbranched, and unlimited covering surface over

. For this purpose we construct a two-sheeted, unbranched, and unlimited covering surface over ![]() as follows. Cut

as follows. Cut ![]() along

along ![]() , take two copies of this cut surface and identify the edges of the slits criss-cross. Put abstractly, this amounts to the following. To each point

, take two copies of this cut surface and identify the edges of the slits criss-cross. Put abstractly, this amounts to the following. To each point ![]() of

of ![]() we associate two points “over it,”

we associate two points “over it,” ![]() and

and ![]() . If

. If ![]() is a point not on

is a point not on ![]() , τ0 = τ(

, τ0 = τ(![]() ), and

), and ![]() an arbitrary (τ − τ0)-disc which does not intersect

an arbitrary (τ − τ0)-disc which does not intersect ![]() , then the points

, then the points ![]() (with upper index 1) which lie over the interior points

(with upper index 1) which lie over the interior points ![]() of

of ![]() constitute a “neighborhood” of

constitute a “neighborhood” of ![]() ; those points

; those points ![]() over the same points

over the same points ![]() constitute a “neighborhood” of

constitute a “neighborhood” of ![]() . On the other hand, if

. On the other hand, if ![]() is on

is on ![]() , let

, let ![]() denote an arbitrary (τ − τ0)-disc. Those points

denote an arbitrary (τ − τ0)-disc. Those points ![]() whose trace points

whose trace points ![]() lie inside

lie inside ![]() and satisfy the condition V ≥ V0, together with all points

and satisfy the condition V ≥ V0, together with all points ![]() lying over inner points

lying over inner points ![]() of

of ![]() which satisfy the condition V < V0, shall constitute a “neighborhood” of

which satisfy the condition V < V0, shall constitute a “neighborhood” of ![]() . The neighborhood of

. The neighborhood of ![]() is defined analogously. In the last case all the points in

is defined analogously. In the last case all the points in ![]() at which V = V0 certainly belong to

at which V = V0 certainly belong to ![]() ; hence this definition of the concept of neighborhood is in agreement with all the demands to be made of such a definition. If

; hence this definition of the concept of neighborhood is in agreement with all the demands to be made of such a definition. If ![]() does not separate

does not separate ![]() , then it is clear that the manifold just defined also satisfies the condition that any two of its points can be joined by a continuous curve. But the existence of such a covering surface would contradict the fact that

, then it is clear that the manifold just defined also satisfies the condition that any two of its points can be joined by a continuous curve. But the existence of such a covering surface would contradict the fact that ![]() is simply connected.

is simply connected.

The last step in the proof is the demonstration of the following theorem.

There exists at most one real number V0 such that the associated line V = V0 on ![]() is nonclosed.

is nonclosed.

For if there were two such lines ![]() and

and ![]() , say

, say ![]() and

and ![]() then one makes use of a closed line U = U0 completely contained in K0 (U0 is chosen large enough). Let

then one makes use of a closed line U = U0 completely contained in K0 (U0 is chosen large enough). Let ![]() be one of the pieces

be one of the pieces ![]() of the curve

of the curve ![]() ; let

; let ![]() be the piece

be the piece ![]() of

of ![]() . Over the heavily drawn path (Fig. 10, the three segments) in the τ-plane there is a curve in

. Over the heavily drawn path (Fig. 10, the three segments) in the τ-plane there is a curve in ![]() , which covers the path simply, and has no ends on

, which covers the path simply, and has no ends on ![]() . This curve separates the simply connected

. This curve separates the simply connected ![]() into two domains; let

into two domains; let ![]() be that one of the two domains which does not contain the point

be that one of the two domains which does not contain the point ![]() . Again we set

. Again we set

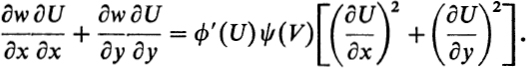

For this function to be continuously differentiable on ![]() , we must have

, we must have

Let ϕ, ϕ′, ψ, ψ′ be bounded and let ϕ′ (except for u = U0) and ψ (except for u = ![]() or

or ![]() ) be positive.38 Then we get a contradiction of the equation D(U, w) = 0. Thus we have proved the following.

) be positive.38 Then we get a contradiction of the equation D(U, w) = 0. Thus we have proved the following.

τ maps the surface ![]() one-to-one and conformally either onto the complete sphere (case 1)

one-to-one and conformally either onto the complete sphere (case 1)

or

onto the sphere with one point τ0 removed (case 2)

or

onto the sphere with a slit V = V0, U1 ≤ U ≤ U2 removed (case 3).

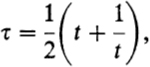

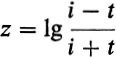

We replace τ by a somewhat different uniformizing variable t. To be sure, t = τ in case 1. In the second case we arrange it so that the point omitted from the sphere is the point at ∞: set t = 1/(τ − τ0); t maps the covering surface onto the whole plane (without the point at ∞). In the third case we first apply an entire linear transformation so that the slit is given by

![]()

Then, with the aid of the formula

the slit τ-sphere is mapped conformally onto the interior of the unit disc | t | < 1 in the t-plane.

The construction we have described of the uniformizing variable t occurs in two clearly separate steps. First, the surface ![]() solves the problem in so far as it belongs to analysis situs. Then the function theoretic theorem, every simply connected Riemann surface may be mapped conformally onto a domain on the sphere, applied to

solves the problem in so far as it belongs to analysis situs. Then the function theoretic theorem, every simply connected Riemann surface may be mapped conformally onto a domain on the sphere, applied to ![]() gives the uniformizing variable. By a slight modification of the argument, one can also show that every planar surface may be mapped conformally onto a domain on the sphere. For nonplanar surfaces this is impossible, for reasons of analysis situs: there will not exist even a topological map onto a domain on the sphere. Every uniformizing variable belonging to

gives the uniformizing variable. By a slight modification of the argument, one can also show that every planar surface may be mapped conformally onto a domain on the sphere. For nonplanar surfaces this is impossible, for reasons of analysis situs: there will not exist even a topological map onto a domain on the sphere. Every uniformizing variable belonging to ![]() (unbranched relative to

(unbranched relative to ![]() ) will map a certain unbranched, unlimited, planar covering surface

) will map a certain unbranched, unlimited, planar covering surface ![]() over

over ![]() conformally onto a plane domain. One assigns two uniformizing variables which map the same covering surface

conformally onto a plane domain. One assigns two uniformizing variables which map the same covering surface ![]() onto subdomains of the plane to the same class {

onto subdomains of the plane to the same class {![]() }. The determination of all uniformizing variables requires then the solution of two problems.

}. The determination of all uniformizing variables requires then the solution of two problems.

(1) The analysis-situs problem: to determine all unbranched unlimited planar covering surface ![]() of a given surface

of a given surface ![]() .

.

(2) The conformal mapping problem: to find all possible conformal maps of a planar surface ![]() onto a plane domain.

onto a plane domain.

That the last is always possible in at least one (and hence in infinitely many) way (in other words, that every class of uniformizers {![]() } conceivable under the analysis-situs condition of planarity actually exists in the function theoretic sense) is the content of Koebe’s general uniformization principle.39 As a matter of fact, this principle goes even further; it includes not only the uniformizing variables which are unbranched relative to

} conceivable under the analysis-situs condition of planarity actually exists in the function theoretic sense) is the content of Koebe’s general uniformization principle.39 As a matter of fact, this principle goes even further; it includes not only the uniformizing variables which are unbranched relative to ![]() , but also the great multitude of branched uniformizing variables. But without question, the uniformizing variable which we have set up and denoted by t carries more fundamental significance than any other uniformizing variable.

, but also the great multitude of branched uniformizing variables. But without question, the uniformizing variable which we have set up and denoted by t carries more fundamental significance than any other uniformizing variable.

§ 21. Riemann surfaces and non-Euclidean groups of motions. Fundamental regions. Poincaré ![]() -series

-series

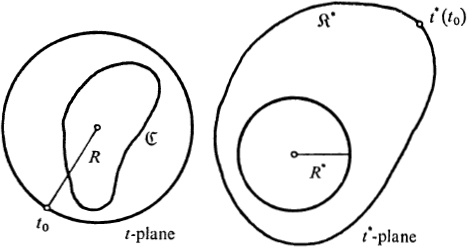

To what extent is the uniformizing variable t determined by the properties stated at the end of the last section? That is, in how many ways can one map the surface ![]() conformally onto the sphere, the plane, or the unit disc? This question obviously comes down to the following: in how many ways can one map the sphere, plane, or disc conformally onto one of these three domains? To begin with, it is clear that the sphere, since it is closed, can be mapped onto neither the plane nor the disc. Also, a conformal map of the plane onto the disc is impossible. If the function t*(t) transformed the t-plane conformally onto the unit disc in the t*-plane, then it would be an entire function whose absolute value would be bounded by one. By Liouville’s theorem, there is no such function (except for the constants, which make no sense here). Furthermore, the following simple theorems hold.

conformally onto the sphere, the plane, or the unit disc? This question obviously comes down to the following: in how many ways can one map the sphere, plane, or disc conformally onto one of these three domains? To begin with, it is clear that the sphere, since it is closed, can be mapped onto neither the plane nor the disc. Also, a conformal map of the plane onto the disc is impossible. If the function t*(t) transformed the t-plane conformally onto the unit disc in the t*-plane, then it would be an entire function whose absolute value would be bounded by one. By Liouville’s theorem, there is no such function (except for the constants, which make no sense here). Furthermore, the following simple theorems hold.

(CASE 1). The set of conformal maps of the sphere(represented in the usual fashion by a complex variable) onto itself is the set of linear transformations.

(CASE 2). The conformal maps of the complex plane onto itself are given precisely by the entire linear transformations.

(CASE 3). Likewise, the open unit disc can be mapped conformally onto itself only by linear transformations.

Case 1. We have to show that if the t-sphere is mapped conformally onto the t*-sphere, t* = t*(t), so that t = 0 goes into t* = 0 and t = ∞ goes into t* = ∞, then the map must be of the form t* = ct, where c is a constant. Now 1/t* is regular at the north pole (t = ∞) of the t-sphere and has a zero there; so t/t* is regular there. Since the relation t → t* is one-to-one, t* vanishes only at t = 0, where it has a zero of order one; hence t/t* is regular on the complete t-sphere, and is thus a constant.

Case 2. Again we may assume that t = 0 is mapped into t* = 0. Next one has to prove that

The circle | t* | = R* corresponds to a closed curve ![]() in the t-plane; let R0 be the maximum distance of a point on

in the t-plane; let R0 be the maximum distance of a point on ![]() from the origin, and let R be an arbitrary number > R0. In the disc | t | ≤ R, | t* | assumes its maximum, which must be > R* at some boundary point, say t = t0. The image

from the origin, and let R be an arbitrary number > R0. In the disc | t | ≤ R, | t* | assumes its maximum, which must be > R* at some boundary point, say t = t0. The image ![]() , of the circle | t | = R, in the t*-plane cannot meet the circle | t* | = R*; for the circle | t | = R and the curve

, of the circle | t | = R, in the t*-plane cannot meet the circle | t* | = R*; for the circle | t | = R and the curve ![]() , of which those two curves are the images, do not meet in the t-plane. Since the point t*(t0) on

, of which those two curves are the images, do not meet in the t-plane. Since the point t*(t0) on ![]() has an absolute value > R*, we must have | t* | > R* for all points on

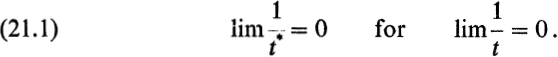

has an absolute value > R*, we must have | t* | > R* for all points on ![]() . That is, | t | > R0 implies | t* | > R*, and this is the claim (21.1). Hence l/t*(t) is regular at the north pole of the t-sphere and has a zero there. The rest of the argument is exactly the same as in case 1.

. That is, | t | > R0 implies | t* | > R*, and this is the claim (21.1). Hence l/t*(t) is regular at the north pole of the t-sphere and has a zero there. The rest of the argument is exactly the same as in case 1.

FIGURE 11

We settle case 3 with the aid of the so-called Schwarz lemma.40 Again we may assume that t = 0 goes into t* = 0. If I consider the regular function t*/t in the disc | t | ≤ q (< 1), it must attain its maximum absolute value on the boundary, and hence this maximum is < 1/q ( | t* | < 1,| t | = q). Since I can choose q arbitrarily close to 1, | t*/t | ≤ 1 must hold at all points of the open unit disc. In a similar fashion, | t/t* | ≤ 1, and hence | t*/t | = 1. This is possible only if t*/t is a constant of modulus one.

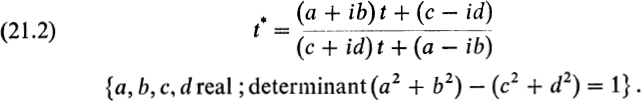

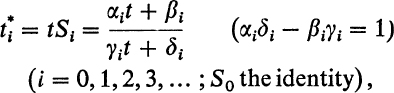

With this the stated claims are demonstrated: the uniformizing parameter t is always uniquely determined to within a linear transformation. The linear transformations which map the open unit disc onto itself have the form

In particular, since the cover transformations of ![]() are one-to-one conformal maps of

are one-to-one conformal maps of ![]() onto itself, these cover transformations must correspond to linear transformations in the t-plane. Thus there corresponds to the group of cover transformations a certain isomorphic group Γ of linear transformations. No transformation of the group Γ (except the identity) can have a fixed point in the image domain (sphere, plane, or disc); a fixed point is a point that goes into itself under the transformation. Since every linear transformation of the sphere has a fixed point, there are no cover transformations in case I, except the identity. Then

onto itself, these cover transformations must correspond to linear transformations in the t-plane. Thus there corresponds to the group of cover transformations a certain isomorphic group Γ of linear transformations. No transformation of the group Γ (except the identity) can have a fixed point in the image domain (sphere, plane, or disc); a fixed point is a point that goes into itself under the transformation. Since every linear transformation of the sphere has a fixed point, there are no cover transformations in case I, except the identity. Then ![]() is the same as

is the same as ![]() , and

, and ![]() is identical, as a Riemann surface, with the sphere. Case I can arise only when the given Riemann surface

is identical, as a Riemann surface, with the sphere. Case I can arise only when the given Riemann surface ![]() is equivalent to the sphere.

is equivalent to the sphere.

The points of ![]() over one point of

over one point of ![]() appear in the map as a system of points t equivalent under Γ. Such a system Σ has the property that any point of the system can be carried into any other by some transformation of Γ; and also, the image of any point of Σ by any transformation of Γ is another point of Σ (see p. 28). The uniform functions on

appear in the map as a system of points t equivalent under Γ. Such a system Σ has the property that any point of the system can be carried into any other by some transformation of Γ; and also, the image of any point of Σ by any transformation of Γ is another point of Σ (see p. 28). The uniform functions on ![]() , regular except for poles, appear, when expressed as functions of t, as automorphic functions attached to Γ. That is, functions z(t) which are invariant under the transformations of Γ:

, regular except for poles, appear, when expressed as functions of t, as automorphic functions attached to Γ. That is, functions z(t) which are invariant under the transformations of Γ:

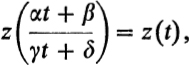

where t* = (αt + β)/(γt + δ) is any transformation in the group Γ. The group Γ must be discontinuous; that is, a system of equivalent points under Γ can never have a limit point in the image domain. If we define a Riemann surface ![]() by taking the “points” of

by taking the “points” of ![]() to be the systems of equivalent points under Γ and by carrying the angular measure in the t-plane directly over to

to be the systems of equivalent points under Γ and by carrying the angular measure in the t-plane directly over to ![]() , then

, then ![]() is equivalent, as a Riemann surface, to the given

is equivalent, as a Riemann surface, to the given ![]() .

.

![]() is the most appropriate normal form into which every Riemann surface can be brought.

is the most appropriate normal form into which every Riemann surface can be brought.

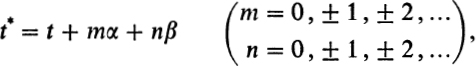

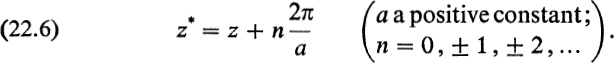

In case 2, Γ must consist of entire linear transformations which have no finite fixed point. The only transformations satisfying this condition are the translations t′ = t + α. A discontinuous group of translations must be of one of the following types.41

(1) Γ contains only the identity. Then ![]() is identical with

is identical with ![]() , and

, and ![]() is equivalent to the plane (the “Simply punched” sphere, that is, the sphere without the north pole).

is equivalent to the plane (the “Simply punched” sphere, that is, the sphere without the north pole).

(2) Γ consists of the iterations of a single translation

![]()

then clearly ![]() is equivalent to the infinitely long right circular cylinder, and hence, by the Mercator projection, to the doubly punched sphere (the sphere without north and south poles).

is equivalent to the infinitely long right circular cylinder, and hence, by the Mercator projection, to the doubly punched sphere (the sphere without north and south poles).

(3) Γ will consist of the transformations

where α and β are translations in different directions. Then ![]() is closed; dt is a uniform differential, regular everywhere on

is closed; dt is a uniform differential, regular everywhere on ![]() , without any zeros, and hence

, without any zeros, and hence ![]() is a closed Riemann surface of genus one. Every such surface - whose type (but not its most general form) is the torus - admits in fact a uniformization by the integral of the first kind, by means of which the universal covering surface is mapped onto the plane.

is a closed Riemann surface of genus one. Every such surface - whose type (but not its most general form) is the torus - admits in fact a uniformization by the integral of the first kind, by means of which the universal covering surface is mapped onto the plane.

Aside from the few exceptions listed above (![]() = sphere, simply or doubly punched sphere, closed surfaces of genus one), case 3, in which the image domain is the open unit disc, always occurs. Since in general the periphery of the unit disc is a natural boundary (cut) for the automorphic functions of t which represent the functions on the base surface

= sphere, simply or doubly punched sphere, closed surfaces of genus one), case 3, in which the image domain is the open unit disc, always occurs. Since in general the periphery of the unit disc is a natural boundary (cut) for the automorphic functions of t which represent the functions on the base surface ![]() , one calls t a cut-circle uniformizing variable [Grenzkreis-Uniformisierende].

, one calls t a cut-circle uniformizing variable [Grenzkreis-Uniformisierende].

The group Γ is not determined uniquely by the given surface. For t may be replaced by any variable t′ obtained from t by a linear transformation T0 which preserves the open unit disc. This transforms Γ into the group

![]()

We introduce the following terminology. Any point t of the open unit disc is a “point of ![]() .” For the “straight lines in

.” For the “straight lines in ![]() ” we take the circular arcs in

” we take the circular arcs in ![]() which are orthogonal to the unit circle (the diameters of the unit disc are included in these “straight lines”). Any linear transformation preserving the open unit disc is a “motion in

which are orthogonal to the unit circle (the diameters of the unit disc are included in these “straight lines”). Any linear transformation preserving the open unit disc is a “motion in ![]() ”; two point sets in

”; two point sets in ![]() are “congruent” if one can be carried onto the other by a “motion.” The usual angular measure is retained. Then the complete Bolyai-Lobatschefsky geometry holds for these “points” and “straight lines.” That is the geometry whose axioms are the same as the axioms of Euclidean geometry, except that the parallel axiom is omitted.42 So we may call

are “congruent” if one can be carried onto the other by a “motion.” The usual angular measure is retained. Then the complete Bolyai-Lobatschefsky geometry holds for these “points” and “straight lines.” That is the geometry whose axioms are the same as the axioms of Euclidean geometry, except that the parallel axiom is omitted.42 So we may call ![]() the non-Euclidean plane. The complex variable t (restricted by the inequality | t | < 1) is to be regarded as a coordinate representing the points in the Lobatschefskian plane, in the same way that the rectangular Cartesian coordinates x, y, or their complex fusion z = x + iy, represent the points of the Euclidean plane. Any linear transformation of t which preserves the unit disc provides another equally valid coordinate system for the Lobatschefskian plane. In this interpretation, Γ now appears as a group of motions of the non-Euclidean plane; or, more precisely, as a representation of such a group by means of a definite coordinate t. If we replace t by t′ obtained from t by a linear transformation preserving the unit disc, then the new group Γ′ thus obtained is to be regarded as a different representation of the same group of motions of the non-Euclidean plane (with the aid of another coordinate t′). There are no rotations in Γ, that is, no motions of

the non-Euclidean plane. The complex variable t (restricted by the inequality | t | < 1) is to be regarded as a coordinate representing the points in the Lobatschefskian plane, in the same way that the rectangular Cartesian coordinates x, y, or their complex fusion z = x + iy, represent the points of the Euclidean plane. Any linear transformation of t which preserves the unit disc provides another equally valid coordinate system for the Lobatschefskian plane. In this interpretation, Γ now appears as a group of motions of the non-Euclidean plane; or, more precisely, as a representation of such a group by means of a definite coordinate t. If we replace t by t′ obtained from t by a linear transformation preserving the unit disc, then the new group Γ′ thus obtained is to be regarded as a different representation of the same group of motions of the non-Euclidean plane (with the aid of another coordinate t′). There are no rotations in Γ, that is, no motions of ![]() which leave some point of

which leave some point of ![]() fixed.

fixed.

Thus to every Riemann surface (aside from the four exceptions already listed) there corresponds a single uniquely determined discontinuous group Γ of motions of the Lobatschefskian plane; and Γ contains no rotations. Two Riemann surfaces are conformally equivalent (as Riemann expressed it, belong to the same class or are realizations of one and the same ideal Riemann surface) if and only if the associated groups of non-Euclidean motions are congruent in the sense of Lobatschefskian geometry. Conversely, to every rotation-free discontinuous group of non-Euclidean motions there corresponds a definite class of Riemann surfaces. (The surface ![]() constructed on page 169 will serve as a representative of this class.43)

constructed on page 169 will serve as a representative of this class.43)

To present a discontinuous group Γ of motions of the n-E plane44 in a more visual fashion, one uses, following Klein and Poincaré, a simple gapless covering of the plane by n-E congruent regions (fundamental regions) which are permuted by the motions of Γ. A dissection of this sort, which is as simple as possible, is provided by the following considerations.

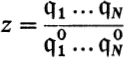

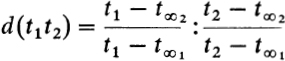

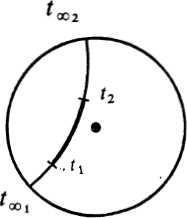

Definition of n-E distance. Let t1 and t2 be any two distinct points in the open unit disc; join them by a n-E line, that is, a circular arc in the Gaussian t-plane which intersects the unit circle orthogonally at t∞1 and t∞2. This circular arc is uniquely determined by t1 and t2. The points on it are to come in the sequence t∞1, t1, t2, t∞2 (Fig. 12). The cross-ratio

has a positive real value > 1, and its real logarithm

![]()

Fig. 12. Non-Euclidean segment.

is positive, r (tl, t2) is invariant under all linear transformations preserving the unit disc. The n-E segment t1t2 is n-E congruent to another such segment ![]() if and only if

if and only if ![]() Furthermore, if the three points tl, t2, t3 lie in that order on an n-E line, then

Furthermore, if the three points tl, t2, t3 lie in that order on an n-E line, then

![]()

Because of these two facts, we shall speak of the number r (tl, t2) as the non-Euclidean distance between the points t1 and t2. Now we are in a position to measure not only angles but also distances in the n-E plane.

If ![]() is a system of equivalent points under Γ, if t0 is a single point of

is a system of equivalent points under Γ, if t0 is a single point of ![]() , and t an arbitrary point of the n-E plane, then because of the discontinuity of Γ there are only a finite number of points of

, and t an arbitrary point of the n-E plane, then because of the discontinuity of Γ there are only a finite number of points of ![]() whose distance45 from t does not exceed an arbitrary given number R. Thus among the points of

whose distance45 from t does not exceed an arbitrary given number R. Thus among the points of ![]() there is one or several (but certainly only a finite number) of points th such that the distance r(t, th) is the smallest distance of t from any point of

there is one or several (but certainly only a finite number) of points th such that the distance r(t, th) is the smallest distance of t from any point of ![]() . Then, as I shall express it briefly, t lies closest to th. If the distance r (t, th) is strictly less than the distance to all other points of

. Then, as I shall express it briefly, t lies closest to th. If the distance r (t, th) is strictly less than the distance to all other points of ![]() , then I can find a neighborhood of t such that every point of this neighborhood lies closest to th. Let th be any point of

, then I can find a neighborhood of t such that every point of this neighborhood lies closest to th. Let th be any point of ![]() ; I collect all those t which lie closest to th into a point set

; I collect all those t which lie closest to th into a point set ![]() with “center” th. The resulting sets

with “center” th. The resulting sets ![]() with all centers in

with all centers in ![]() , have disjoint interiors and cover the whole n-E plane. The transformation of Γ which carries t0 into th carries

, have disjoint interiors and cover the whole n-E plane. The transformation of Γ which carries t0 into th carries ![]() into

into ![]() ; hence

; hence ![]() is n-E congruent to

is n-E congruent to ![]() . To every point t there corresponds a point of

. To every point t there corresponds a point of ![]() which is equivalent to t under Γ; two distinct interior points of

which is equivalent to t under Γ; two distinct interior points of ![]() are never equivalent. Thus

are never equivalent. Thus ![]() has the properties of a fundamental region. Also,

has the properties of a fundamental region. Also, ![]() is convex; that is, if t′ and t″ are any two points of

is convex; that is, if t′ and t″ are any two points of ![]() . then all points of the n-E segment t′t″ joining t′ and t″ belong to

. then all points of the n-E segment t′t″ joining t′ and t″ belong to ![]() . The perpendicular bisector

. The perpendicular bisector ![]() of the segment t0th is the locus of points equidistant from t0 and th; to every th distinct from t0 we obtain such a line

of the segment t0th is the locus of points equidistant from t0 and th; to every th distinct from t0 we obtain such a line ![]() . The boundary of the closed set

. The boundary of the closed set ![]() is composed of segments of these lines; the interior of

is composed of segments of these lines; the interior of ![]() consists of those points which, for every

consists of those points which, for every ![]() , lie on the same side of

, lie on the same side of ![]() as t0. All points of the line

as t0. All points of the line ![]() have a distance

have a distance ![]() from t0, and there are only a finite number of the centers th whose distance from t0 does not exceed an arbitrarily given 2R. Hence it follows that only a finite number of segments on the boundary of

from t0, and there are only a finite number of the centers th whose distance from t0 does not exceed an arbitrarily given 2R. Hence it follows that only a finite number of segments on the boundary of ![]() has a distance ≤ R from the principal center t0. Thus

has a distance ≤ R from the principal center t0. Thus ![]() is a convex polygon, with a finite or infinite number of sides, whose vertices (that is, those points which are equidistant from three or more points of the system

is a convex polygon, with a finite or infinite number of sides, whose vertices (that is, those points which are equidistant from three or more points of the system ![]() ) have no limit point in the finite.

) have no limit point in the finite.

Following Fricke, ![]() is called a normal polygon belonging to the group Γ. The sides of the normal polygon are associated in pairs; either side of a pair can be carried onto the other by some motion in Γ. Two sides with a common vertex are never associated; for such a common vertex would have to be a fixed point of the motion carrying one side onto the other. These motions carrying one side of

is called a normal polygon belonging to the group Γ. The sides of the normal polygon are associated in pairs; either side of a pair can be carried onto the other by some motion in Γ. Two sides with a common vertex are never associated; for such a common vertex would have to be a fixed point of the motion carrying one side onto the other. These motions carrying one side of ![]() onto another (that is, the motions carrying

onto another (that is, the motions carrying ![]() onto a fundamental region

onto a fundamental region ![]() which abuts

which abuts ![]() along some side of

along some side of ![]() ) generate the group Γ. That is, every motion of Γ may be obtained by iterating and composing those particular motions. One proves this as follows. Join an arbitrary point th of

) generate the group Γ. That is, every motion of Γ may be obtained by iterating and composing those particular motions. One proves this as follows. Join an arbitrary point th of ![]() to t0 by a polygonal path which avoids the vertices of the polygonal decomposition {

to t0 by a polygonal path which avoids the vertices of the polygonal decomposition {![]() }. Now observe the succession of polygons in this decomposition through which the polygonal path passes. Suppose there are in all e polygons

}. Now observe the succession of polygons in this decomposition through which the polygonal path passes. Suppose there are in all e polygons ![]() equivalent to

equivalent to ![]() (including

(including ![]() itself) which meet at the vertex 1 of

itself) which meet at the vertex 1 of ![]() . Then there are exactly e centers to which 1 lies closest, and there are e points of

. Then there are exactly e centers to which 1 lies closest, and there are e points of ![]() which are equivalent to 1 under Γ; or, in the terminology of Poincaré, which constitute a cycle of vertices of the polygon

which are equivalent to 1 under Γ; or, in the terminology of Poincaré, which constitute a cycle of vertices of the polygon ![]() . The sum of the angles in

. The sum of the angles in ![]() at the vertices of such a cycle is the full angle 1 (= 360°).

at the vertices of such a cycle is the full angle 1 (= 360°).

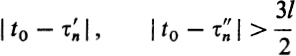

The Riemann surface ![]() (p. 169) belonging to the group Γ is obviously closed if and only if there exists a positive number R such that for every point in the n-E plane there is at least one equivalent point under Γ whose n-E distance from the center t0 is ≤ R. Then every point has a distance ≤ R from the closest point in the system

(p. 169) belonging to the group Γ is obviously closed if and only if there exists a positive number R such that for every point in the n-E plane there is at least one equivalent point under Γ whose n-E distance from the center t0 is ≤ R. Then every point has a distance ≤ R from the closest point in the system ![]() ; in particular,

; in particular, ![]() is completely contained in the n-E disc of radius R about t0. Since the vertices of

is completely contained in the n-E disc of radius R about t0. Since the vertices of ![]() cannot have a limit point in the finite, there are, in this case, only a finite number of such vertices :

cannot have a limit point in the finite, there are, in this case, only a finite number of such vertices : ![]() has finitely many sides. Let the number of sides of

has finitely many sides. Let the number of sides of ![]() , which must be even because of the pairing of the sides, be 2s; let c denote the number of distinct vertex cycles of

, which must be even because of the pairing of the sides, be 2s; let c denote the number of distinct vertex cycles of ![]() , so that c is also the sum of the angles in

, so that c is also the sum of the angles in ![]() . We wish to show that the genus p of this closed Riemann surface may be computed from s and c by the simple formula

. We wish to show that the genus p of this closed Riemann surface may be computed from s and c by the simple formula

![]()

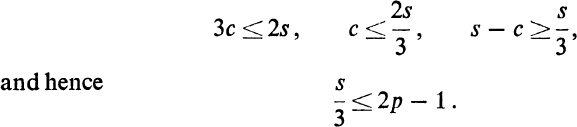

Since every cycle contains at least three vertices, we have

Therefore 12p − 6 is an upper bound for 2s, the number of sides or vertices of a normal polygon.

We choose t0 = 0. The (n-E as well as Euclidean) linear segments joining 0 to the vertices of ![]() separate

separate ![]() into 2s triangles. This provides a triangulation of

into 2s triangles. This provides a triangulation of ![]() into 2s triangles with 3s edges and c + 1 vertices. Then, from the most basic formula of combinatorial topology, the genus p is in fact determined by the equation

into 2s triangles with 3s edges and c + 1 vertices. Then, from the most basic formula of combinatorial topology, the genus p is in fact determined by the equation

![]()

In this book we have adopted the methodological attitude of avoiding boundaries as much as possible, and we have operated with coverings by overlapping neighborhoods rather than with dissections into simple pieces of surface. The appeal here to combinatorial topology would introduce a foreign element. Therefore, instead of this topological proof of the equation (21.3), I prefer a function theoretic proof. It runs as follows.

We take a meromorphic differential dz on the closed surface ![]() . As we know, its order is 2p − 2. We shall assume for the moment that none of the zeros or poles of dz lie on the sides of

. As we know, its order is 2p − 2. We shall assume for the moment that none of the zeros or poles of dz lie on the sides of ![]() . Consider the analytic function dz/dt of t in the region