At the Sharp End: Tales from the Troops

Like all organizations, Airfix is the sum of its parts and the most important component of any successful business is its staff. Unlike so many other companies, Airfix seems to have engendered a feeling of real kinship between itself and the employees it relied upon for commercial success.

Whilst there’s no doubt that at times there was a ‘them and us’ element in the operational management of Airfix – loyal staff felt seriously let down when what they perceived as a large and stable group collapsed so quickly in 1981, leaving them high and dry – every ex-employee I’ve spoken to has only the fondest memories of their time with the firm.

For thirty years I’ve been interviewing those who have worked at Airfix and during all that time I’ve learned that there is something pretty special about working for the company. I have spoken to individuals working in areas as apparently disparate as financial management and toy design and in each case have discovered the kind of camaraderie that is unusual in other manufacturing industries.

Today, every time I visit Airfix at its new home in Kent, I am struck by the friendliness and, yes, team spirit, of everyone I meet.

In the previous chapter we embarked on a chronological journey through the history of toy, game, arts and crafts design and development. Now it’s time to hear from some of those at the coal face whose efforts contributed to Airfix’s success during its heyday.

We heard from Mary Wright, Arts & Crafts product manager, in the previous chapter. I was also lucky enough to revisit Mary and talk, both to her again, and her sister-in-law, Sue Wright, who worked as Airfix’s press officer in the 1970s.

Having previously worked for an accountancy firm, Sue joined Airfix in June 1970, employed as personal secretary to Michael Loveland, Airfix’s merchandise manager. Sue told me that when she was first at Airfix she also used to do some typing for Harry Lambert, then the tool shop manager.

‘He used to produce all sorts of complicated calculations regarding the amortization of the cost of the tool, how long it would take before Airfix got its money back – how many models it had to make and sell to cover the cost of tooling,’ she said.

Her employer soon recognized that her talents were being underutilized and it didn’t take long for Sue to climb the promotional ladder. In 1973 she became Airfix’s press officer. Although Sue left in 1975, she has fond memories of her time there.

I was particularly fascinated to hear about comedian Dick Emery, the company figurehead at the time, whose smiling face regularly appeared in boys’ comics alongside a chirpy ‘Hello Mates!’ as he unveiled a new competition or whatever.

On the left, Sue Wright, next to her sister-in-law, Mary Wright, at Mary’s home in Cheam in 2011.

‘Although he was President of the Airfix Club, he never came to anything; he was just a figurehead, despite the fact that we were always trying to get him along to sign something or turn up for a photo session,’ Sue told me.

Readers of a certain age who remember Mr Emery might actually be surprised to learn that he was indeed a keen scale modeller and actually penned a large article about his passions for Meccano Magazine in 1971. Another surprise: Dick Emery had also held a private pilot’s licence since 1961.

Press Officer Sue Wright presenting model Airfix Lightnings at RAF Wattisham on the occasion of the aircraft’s retirement there in 1974.

As keen-eyed readers will have noticed on a previous page, Airfix Press Officer Sue Wright even appeared on the packaging of Big Ear, one of 1974’s new games.

‘He seemed quite an unlikely person to have as a figurehead. However, I’m not even sure if there was any money involved or if he ever got paid!’ said Sue.

Sue’s even not sure how Mr Emery first got involved with Airfix but it seems likely that the then editor of Airfix magazine, Chris Ellis, contacted the comedian following publication of the feature in Meccano Magazine revealing the funny man’s interest in scale models.

In the early 1970s, when BBC TV was screening its seminal drama about Colditz Castle, Airfix released a rather neat model – well, toy, really – of the glider that prisoners secretly built in one of the attics of the fortress.

When he came to a meeting at Haldane Place Sue remembers meeting Major Pat Reid MBE MC, who, as a British prisoner of war during the Second World War was one of the few to escape from Colditz, crossing the border into neutral Switzerland in late 1942. Pat Reid’s endorsement of Airfix’s new toy added credibility to the replica glider in the same way it did for the BBC TV show.

It wasn’t all plain sailing, though. Sue recalls a furore when the latest Airfix catalogue, featuring the prestigious new glider, was about to go to print. The carelessness of a designer almost resulted in the publication being distributed featuring a photo that showed what Sue called ‘a great lump of Plasticine and some sticks’ protruding from the glider’s fuselage. These supports were supposed to be a temporary expedient used to anchor the model while it was being positioned prior to the final photograph. Fortunately, after seeing their presence on the preparatory Polaroid, taken as a kind of proof before the real film was exposed, the errant scaffolding was removed.

The Airfix Modellers Club president appeared in regular ads in the popular boys’ comic Valiant. This one is from 1975.

Catalogue illustration showing the original glider being assembled high up in the attic of the infamous Colditz Castle.

Despite this hiccup, the Colditz Glider went on to do rather well, helped perhaps by the catalogue’s claim that the toy consistently achieved level flights of nearly 100ft. Happy purchasers could therefore achieve something that eluded Major Reid and his colleagues: actually flying what the Airfix catalogue called the ‘best kept secret in Colditz’. Because of the fortress prison’s liberation by US troops in April 1945, the real glider never left the ground, or, more precisely, the attic floor.

Mint and boxed Airfix Colditz Glider, so rare and valuable that no collector dare risk flying one – unless they had a spare!

Other than the occasional feature in the Daily Mirror about a girls’ toy or perhaps answering a request to supply photographs of a new model or toy relevant to the anniversary of a wartime campaign, Sue was more involved with the trade press than the national newspapers.

A big part of her job was compiling specifications and product details and arranging photography for a new toy or kit prior to the review being distributed to the toy and hobby trade.

The aforementioned oil crisis occurred slap bang in the middle of both Sue and Mary’s time at Airfix. Mary recalled that the price of plastic rose dramatically during this period and even had a rather unexpected effect on company perks.

‘All Airfix company cars were reduced to Minis,’ she told me, ‘and the big ones, such as John Gray’s Jensen Interceptor, were stashed away somewhere!’

Mary and Sue told me that they both enjoyed trying out Airfix’s new toys and games. ‘We used to play some of the toys to death,’ said Mary.

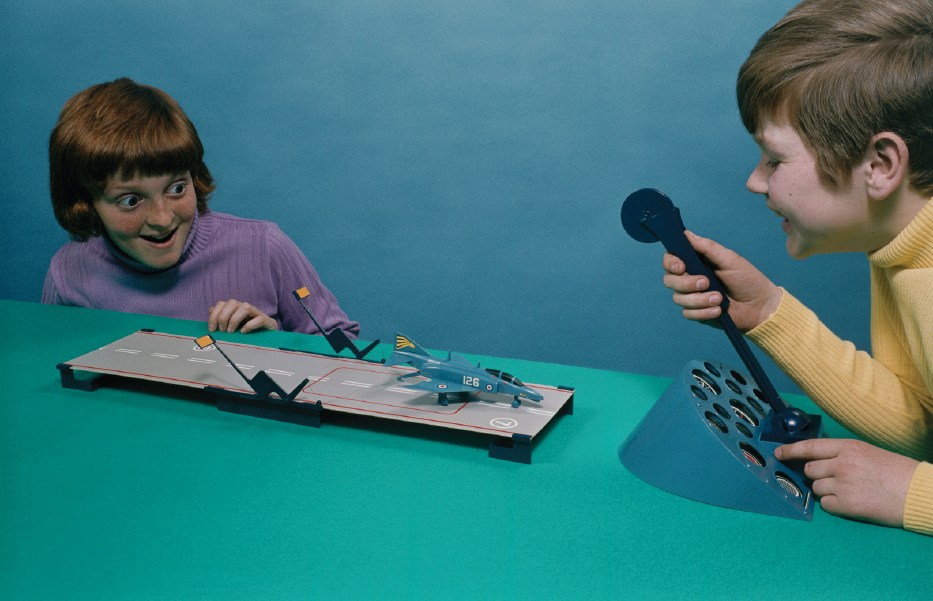

Flight Deck. It promised a lot and looked great, but landing a Royal Navy F4 Phantom onto the cardboard deck of an aircraft carrier while it dangled from nylon thread somehow failed to simulate the drama of the real thing.

Super Flight Deck, in particular, was a favourite of Sue’s.

‘I loved Super Flight Deck – it was such a good thing to play with, such a good toy.’

Mary and Sue told me there was heated debate in the upper echelons at Airfix prior to the national TV campaign for Christmas 1974, Airfix’s first and massively expensive TV offensive.

‘I can remember the controversy about doing a TV commercial, because we hadn’t done one before,’ said Mary.

‘I remember going to the shoot for the Weebles,’ said Sue, on duty as part of her job as press officer to ensure that everything went to schedule and that ad agency Gray stuck to the brief. Part of this duty also required Sue to regularly attend creative and media presentations at Gray’s Savile Row offices.

Sue and Mary remembered that there was a pretty good staff shop where employees could purchase Airfix goods at a discounted rate but they both agreed that the best in-house service was Airfix’s canteen. There you could purchase incredibly good stodgy grub. ‘And it wasn’t a “them and us” situation,’ recalled Sue, although she did confess that there was an executive canteen at the back where the top brass and visiting dignitaries dined. The pair reckoned that there must have been somewhere around 150 staff based at Haldane Place.

‘I think that one of the nicest things about Airfix was that it all happened on one site, or practically all of it. They even designed tools, or some of them, required to maintain the plant and keep the injection machines running,’ Sue told me.

As we have seen, by the late 1970s, the Airfix empire comprised far more than just one location in a single country, it amounted to several factories and administrative centres spread all over the world. However, there’s no doubt that home was Haldane Place, the factory complex in Wandsworth to where Airfix had moved when they outgrew their North London premises in 1949. It wasn’t long before they needed even more space at their new home and they very quickly expanded towards Garrett Lane, where they occupied the site previously owned by the Bendon Valley Laundry.

Much of the original premises remain, although no obvious trace of Airfix survives and the site has now been rebranded Riverside, a series of commercial offices and light industrial spaces leased by the Workspace Group. On the site occupied by Airfix’s large mould shop and plastic store a large Mecca Bingo club now stands, but some key buildings survive – not least the three-storey block within which many of the stories recounted on these pages actually took place.

Plastic Kits, Airfix’s flagship line, sat, fittingly perhaps, at the top of the building, on the third floor. Jack Armitage’s office was situated up here, as was the drawing office where Peter Allen and others earned their daily bread. This space was equipped with drafting tables, complete with parallel motions (no computer software to ensure perfect 90° angles each and every time) and a photographic darkroom.

View of the far end of Airfix’s Development Workshop. Chas Emmerson, the star of Airfix Railways, is at his desk in the middle distance.

Both the Airfix Arts & Crafts and Toys & Games divisions shared the second floor. There was, however, a separate office, first for John Hawks and then for Chris Hood, each of whom respectively managed Toys & Games in the 1970s.

There was also a joint reception for both of these divisions, and the Development Workshop, where prototypes were fashioned. This workshop was, said Graham Westoll, ‘complete with lathe, stand drill, acid bath and other weird stuff.’

On the ground floor stood Dept C, the department that used to send out missing and replacement kit parts. They also used to make up kits for trade shows, photo shoots and PR events. The majority of the staff there were either physically or mentally challenged. They were, said Graham again, ‘all very nice people and comprised many excellent model makers.’

Graham and Sue today.

Graham Westoll spent five and a half happy years at Airfix, joining in 1974 as assistant product manager to Mary Wright, who was then head of the Arts & Crafts Division. He was employed to fill the vacancy left by Sue Godfrey, a designer/illustrator who had joined Airfix in 1972, but had left after little more than a year to pursue her freelance career. Airfix, however, remained one of Sue’s biggest clients and she had frequent dealings with Mary.

‘When Sue left, Mary put out an advert for assistant product manager, which is what I saw and applied for,’ said Graham. ‘I didn’t really know much about what the job involved and I wasn’t really that interested in painting by numbers. But it was “Airfix”. I thought, “I like making kits and it’s a famous brand,” and my background was as an illustrator doing artwork for children’s books, that sort of thing, so there seemed to be a synergy, and I got the job,’ said Graham.

‘I think Mary’s thinking when I turned up may have been to introduce a male element. Obviously Airfix was all about kits – Stukas and Messerschmitts – and salesmen loved selling those. But ask them to sell prancing ponies or ballerinas and it was, “Uh, big girl’s blouse stuff!” So I think what Mary might have been looking for was an element of brand expansion, perhaps by introducing a male element to Arts & Crafts. So I ended up with the job and was taken on as assistant product manager.’

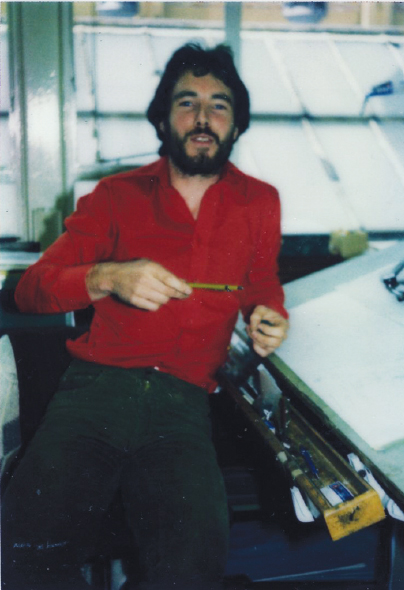

Sue Godfrey at her desk in the early 1970s.

Shortly after Graham joined, Mary left, having fallen pregnant with her first child.

‘As I was still seeing Mary throughout that time, doing freelance work for her, I asked if I could go back to Airfix. She said yes and jumped at the idea,’ said Sue.

Consequently, during the period covering the second half of the decade, Airfix Arts & Crafts was jointly managed by the pretty unique partnership of Graham and Sue. As joint product managers they continued with the task of building upon Mary’s impressive legacy. Unlike the managers of the Toys & Games Division, Graham and Sue worked alongside other staff, not in an office.

Before she joined Airfix in September 1972, Sue, who had art school training, previously worked for a printer and a small advertising agency. ‘Funnily enough, my dad worked in the toy trade; he was sales director for a wholesale company, and when he saw that there was a job coming up with Airfix he said, “You’ve got to go for it!”’

While she had been working at the printing company Sue had done some artwork for a Painting by Numbers box, which she took to her interview with Mary Wright, then head of Arts & Crafts at Airfix.

‘Although I took this artwork along to Airfix, I didn’t know they were involved with arts and crafts, but when Mary saw my Painting by Numbers art, that was it. I got the job.’

Although Mary was officially Product Manager, Airfix Arts & Crafts, she was effectively a one-man band and in real need of support. Sue was the ideal candidate.

‘Mary was developing the range far beyond the original limited range of products Airfix had previously sold,’ Sue told me. ‘My first job there was to do mock-up packs for Craft Kits. There were about twenty-four of these little poly bags full of bits and pieces and you could make finger puppets or felt flowers or things made from tissue paper. When I joined, Mary was about halfway through the range. She was very interested in sewing and tended to involve herself with such items. I began with mobiles, greetings card kits and the napkin rings – just a bit of raffia around a section of cardboard tube! And that’s how it started. All these were designed at Airfix,’ said Sue.

Before Mary rolled up her sleeves and decided to reorganize the Arts & Crafts Department, most new ideas were developed stateside. ‘Mary very much wanted to develop her own things and the Craft Kits were the first steps,’ said Sue. ‘So you got a poly bag with bits of felt in it, with something to sew with and a paper pattern to follow. But what we had to do, it wasn’t just putting them together; we had to source the actual components completely.’

Sue said the buying office at Airfix would find the suppliers but she and Mary were responsible for costing them and budgeting for the investment. ‘From what I can remember we were more or less working back from what the retail selling price would be,’ she reflected. ‘So when we were looking at buying the components, as a rule of thumb we would multiply the cost of components by four, and you had your selling price. It was just a rough guide but we knew that if we could get something in for 10p we could sell it for 50p.’

Sue said she was originally tasked with coming up with a selection of two dozen Craft Kits, ‘the objective being to fill a whole stand with them.’

‘For many years, Airfix had been extremely strong in the pocket money market. In numerous corner shops and independent toy stores you always found a rotary display stand covered with Series One and Series Two kits,’ said Graham.

The Arts & Crafts range also had its own entry level, or starter range, Mary’s unique range of Craft Kits. ‘These were low in cost to manufacture but also targeted a rather gender specific target market, although there was a model glider, based on the Me 262, I think,’ said Graham.

‘One problem with these items was in-store display They needed to be put on wall pegs but these were usually taken up by kits and if they were put on a shelf would fall down or just be stacked in a jumble. It was time to come up with something new.’

Two boxed and one loose Airfix/Bachmann Mini Planes Ju87 Stukas. Although tiny, these miniature ready-mades featured astonishing detail for the time, 1970.

The issue of display was solved by putting these kits in triangular shaped boxes, sold to the stores in rip-top display boxes each containing twelve kits, which were randomly assembled.

Graham told me that at the first Birmingham Toy Fair the gliders were incredibly popular and a competition was run to see how far and how high people could fly one. ‘The winner was a guy who landed one of the planes on one of the massive girders in the roof of the exhibition hall, about 40 to 50 feet up!’

Mary Wright said that preparing the instructions for the various craft sets was time consuming, very precise work, but that Sue Godfrey had a particular facility for doing them well and accurately.

‘Sue had been involved with Mary and Arts & Crafts prior to my getting involved,’ said Graham. ‘But when I joined I understood that previously the Painting by Number range had been bought in from Craft Master in America and repackaged in an Airfix/UK type branding. Mary and Sue brought on a new, home-grown range of quite varied craft items.’

When Sue and Graham took up the mantle of Airfix Arts & Crafts between them they enjoyed unique freedom. When it came to deciding on what to introduce into the growing range, ‘everything had already been done with the imported, licensed American arts sets – all we had to do was take a photograph and apply a “tip on” (a loose-leaf, colour-printed plate as was common in illustrated books from the Edwardian period) of the picture inside the package, which was stuck onto a standard box exterior,’ said Graham. Although there wasn’t much individuality involved in the rebadged American items, ‘the crafts, however, were something new.’

Sue left Airfix after little more than a year and went freelance. She continued to be closely involved with Airfix, however, as Mary Wright continued to employ her talents for much of the artwork for the blossoming Arts & Crafts range.

Graham, who joined Airfix shortly after Sue had left, said, ‘I emerged on the scene like a weed, my first catalogue being in 1974 and Glitter Pictures being the first product I was involved with.’

Graham enjoyed working for Mary and learned a lot from her. ‘She was a very driven person. You have to remember that she was the only female product manager in the company at the time, a very male centric company in those days. She was possibly one of the highest ranking females in the company but she had had to fight her corner to achieve this. These days a product manager is a number cruncher. In those days, product managers where very hands-on, working from the initial idea right through to post delivery. Mary clearly had an ambition to grow her product range and had obviously been working closely and well with Sue.’

At the time neither Graham nor Sue knew if Mary would return to Airfix following maternity leave. Nevertheless, Graham believes that his boss executed a pretty good game plan to ensure that Arts & Crafts developed in the way she had foreseen and worked so hard to achieve.

‘Mary was very much the owner of Arts & Crafts; she had to be, and she therefore put together a plan for how it was going to carry on. Sue and I have debated about whether or not Mary was going to return to Airfix. I think she espoused that she would do but becoming a mum changes everything and she never came back.

‘I think one of the very crucial decisions Mary made was getting me on board to add some male influence, but working alongside a woman,’ Graham reflected. ‘She could have simply backed away and gone on maternity leave and I would have stepped up to be the product manager to stand in for her. But that would have left a man in charge of Arts & Crafts. With hindsight, I think the wisest decision she made was to make it a doubleheaded game so that Sue and I became joint product managers.’

‘But apart from that,’ Sue interjected, ‘it was too big a department for someone to manage on their own.’

‘There would have been a risk that if one person had been left in charge of Arts & Crafts on their own the Toys & Games Division could have sucked them in and taken prominence. It needed a team rather than one person, which is how Mary had been. Things were growing, things were developing. Mary had a vision for where she would have liked things to go and Sue and I fulfilled that vision,’ said Graham.

I asked Sue and Graham if Mary had made a real change when she had been at Airfix.

‘Oh yes,’ said Graham. ‘The Painting by Numbers sets were the bread and butter; they were what everyone knew about, but Mary really wanted to push and expand the crafts range alongside them. And at that time her crafts range was growing and selling well. The sales force liked them and we were encouraged to do more and more in this vein.’

Graham continued to stress the changes Mary had brought to her domain in such a relatively short period.

‘Airfix initially got into arts and crafts by licensing Painting by Numbers from Craft Master. They needed someone to run that because it didn’t fit in to the world of kits. Arts & Crafts really needed a female and they found one, which was logical given that most pictures had a strong female element. But rather than just overseeing the repackaging of bought-in products, Mary saw the potential of Airfix crafts items, and that’s where home-grown started to come in. She had made a radical change to the department in terms of where she left it when she handed it over to us. We were given a programme showing where it could go to and we were given her bequest in a way.’

‘Because lots of the things we worked on were brought in from America, they weren’t always right for our market, a bit cheesy, in fact. We often had to put a British slant on things,’ said Sue.

Graham told me that when he was with Airfix their ‘arch-rival’ was Waddingtons, who began game production in 1922, creating both their own products and games licensed from other publishers. They were eventually bought by Hasbro in 1994.

‘If you want a lovely little anecdote, our arch-rivals were at one stage Waddingtons’ Art Master Painting by Numbers and our flagship painting was The Mona Lisa. Their flagship painting was The Laughing Cavalier. At the Garratt Lane end of Haldane Place stood a great big forty-eight-sheet poster board. Waddingtons’ media agency bought it and put up the famous advertisement they did in co-operation with Heineken, which showed a Painting by Numbers portrait of The Laughing Cavalier transforming into a real life character as he drinks a can of the eponymous lager. Waddingtons had got that at the end of our road! They had got their flagship on our turf. They were our big rivals.’

Sue and Graham’s responsibilities were supposedly divided between Arts & Crafts. ‘One of us was arts range manager and one of us crafts range manager but I can’t remember which was which,’ she laughed.

‘Exactly! But, if you like, it was like trying to separate conjoined twins, because any idea I came up with I would bounce off Sue and any idea I originated she would tear apart. Actually, our relationship was totally synergistic, but I think Sue stayed purer,’ said Graham.

Although actually employed in the Arts & Crafts Department, on occasions Graham became closely involved with Kits.

In 1978, Jack Armitage, Airfix’s chief designer, asked Graham what could be done to breathe new life into a series of car moulds that had effectively become redundant. ‘As I understand it Airfix had a load of moulds for classic car kits that were no longer selling – Sunbeam Rapiers, Vauxhall Crestas and the like. No interest. Their options were either to trash them, see if you could license them off to Heller or somebody else, or just leave them sitting in the oil baths. “Can we make something of these?” was the challenge I was given.

‘It was the time of the King’s Road cruises, where enthusiasts drove along with jacked-up rear wheels and the like. I got asked to see if I could do something with our old kits and breathe new life into them, similar to what was happening on the streets.

‘The guys on the upper floor knew how to make a precise 250th reduction of a rivet head on a Stuka,’ said Graham. ‘That was their craft. But thinking outside the box, if you like, is more of an arts and craftsy sort of thing, so the project came downstairs and it came to me.’ Graham joked that perhaps the Kit Division was prepared to let a member of Arts & Crafts, albeit a chap, loose on one of their beloved models, ‘because the project was a bit boyish with no stitching involved!’

The kit team required Graham to keep expensive modifications, other than perhaps tamping off unneeded parts on the mould runners, to a minimum, thereby keeping tooling costs down. Whatever he did come up with, Graham was expected to suggest ideas that upheld Airfix’s reputation for reality and precision. Despite these not unreasonable restrictions, Graham decided that certain existing tools could indeed be economically converted.

Graham had settled on rejuvenating a series of classic car moulds, which were in good condition but had fallen out of fashion with customers. A series of customized street cars would be the phoenix that rose from the ashes of obsolete kit parts. And other than a few small additions to the existing tools, about all that was required was new decal sheets and, of course, new packaging.

Featuring a host of colourful graphic embellishments, in no time at all and with minimal investment, a small range of Airfix classic cars were converted into stylish roadsters. The old Ford Zephyr, previously famous for its role in TV’s Z-Cars, became Night Prowler, a homage to a US cop’s black and white cruiser. The simple addition of a spoiler and an all-over body wrap turned the veteran Airfix Ford Capri into Krackle Kat.

In 1975, Airfix released a new doll, Tiny Tickle Me. However, when Ernest Bultitude, the then marketing manager, tore open boxes of the 1976 Toys and Games catalogue, just before they were distributed at the January toy fair, to his horror he discovered a very sloppy bit of typesetting. ‘Just like a real baby, Tiny Tickle Me will throw up,’ read the caption beneath the catalogue illustration of this new toy. Readers had to turn the page to reveal the second, important part of this sentence: ‘… her hands and kick her legs in the air when her tummy is tickled.’

Another blooper, and this time within Graham and Sue’s direct domain of Arts & Crafts, concerned Airfix Painting by Numbers. More significantly it involved Airfix’s flagship product in this range – The Mona Lisa. As you might imagine for such a masterpiece, da Vinci’s classic required the inclusion of quite a number of subtle shades and hues, skin tones especially, if purchasers of Airfix’s interpretation of The Mona Lisa was going to come anywhere close to the priceless masterpiece hanging in The Louvre.

There were plenty of colours to choose from. In fact, 360 different paints were stocked at Airfix’s Charlton production facility. Alf Giddings, the production manger there, had what Graham told me was a fantastic knowledge of the entire Arts & Crafts range and in particular knew the code of every tiny pot of oil paint off by heart. ‘He carried the entire range in his head. He knew what were the blues, reds, pinks and browns and he knew the code classifications for all 360,’ said Graham. ‘Whenever a colour went out of stock he could substitute it with the nearest equivalent. Just like that. Or so we thought!’

Graham told me that on one memorable day the production line supervisor at Charlton told Alf that a particular shadow colour, used to add definition to The Mona Lisa’s jaw line, was out of stock. In no time at all Alf proposed a substitute, reeling off the particular code number by rote, suggesting No. 150, for example, as a substitute for, let’s say, No. 257. The chosen paint pot was then inserted into the appropriate hole punched into the cardboard palette in the box. Activity on the production line resumed and stocks of complete Mona Lisa sets were despatched to the trade.

All was hunky-dory. Or that’s what everyone thought, until Airfix began to receive a series of identical complaints about the New Artist Mona Lisa. Customers bemoaned the fact that when they approached the subtle contours of The Mona Lisa’s jaw line, selecting the particular paint from the palette as instructed, they discovered that instead of adding relief to the enigmatic model’s lower face, to the contrary, they’d given her a beard. Alf Giddings had chosen a distinct shade of brown rather than a subtle, shadow flesh tone.

In the search for a solution to this problem Sue and Graham were tasked with speaking to ICI Paints in Slough to talk to them about their recently launched paint tinting system, which had just started to appear in major DIY stores.

‘It was a rather embarrassing day when we sat with their technical team to describe our requirements – a system that would allow Charlton to produce paints on-site so as not to run out of essential colours,’ remembered Graham. ‘The problem was that our requirement involved capsules of paint that were only 2cl in volume. With a very sympathetic smile the ICI guys explained that their system was designed to tint quantities of no less than half a litre! In fact, the quantity of tinter they used on their machines exceeded 2cl by a factor of over fifty!

‘We went away feeling a bit silly but with their best wishes,’ an embarrassed Graham recalled with smile.

When Sue and Graham first joined, the entire Airfix kit and caboodle (no pun intended) was managed by John Gray. Then came John Abbott, ex-Slazenger and naturally very focused on developing Airfix’s sports range. Ken Asquith, who had previously worked very closely with the legendary Gray, took over from his mentor. Finally, in 1979, David Sinigaglia was Airfix’s managing director. In fact, for most of Sue and Graham’s time at Airfix, John Abbott, who Sue called ‘a terribly nice guy’, was at the helm.

‘We were the Development Office but right behind us was the Development Workshop,’ explained Graham. ‘Those guys cut metal, made prototype tools and worked out how to articulate toys and dolls, that sort of thing – the physicality of things, which really evolved with the trains. In fact, that was when the division between that department [the workshop] and those upstairs really began to blur. You needed the combined talents of the kit designers and those in the workshop to make a success of things.’

Because Sue and Graham in Crafts could make their own prototypes the Development Workshop was mostly used by the Toys & Games Division, for example, creating memorable patterns for the Fighter Command game and the new animatronics doll, Tiny Tickle Me. Increasingly, however, the workshop got involved in preliminary design work for Airfix model trains as this area expanded rapidly in the late 1970s.

Despite having fully developed divisions across the spectrum of toy and hobby products that youngsters, or rather their parents, were likely to purchase, Graham recalls that at the end of the day Airfix was first and foremost a kit company. Indeed, Ralph Ehrmann once told me that he only kept Toys & Games and Arts & Crafts in the product mix because in the early days he and John Gray weren’t sure if the enormously profitable kit bubble would burst. It was, perhaps, a flash in the pan, and Airfix would have to return to the diversified range of products it began with in the 1940s. Indeed, Graham recalls that when Airfix were offered the chance of introducing multicoloured components before Lesney (Matchbox kits with pre-coloured parts first appeared in 1973) they pooh-poohed the idea. Being traditionalists, Airfix thought that scale modellers would shun such developments. How wrong they were. Lesney grabbed a huge proportion of the market share, rapidly selling into corner shops and model shops, and, as Graham explained, solving one of the classic conundrums about making model kits: most kids could assemble a miniature easily but few of them could achieve even a passable finish with stubby paint brush and oily enamels. Matchbox’s pre-coloured parts went together easily and once the decals were applied, even without a coat of paint they were eminently acceptable.

‘Airfix rejected the idea of blowing three colours into a single mould tool as being too toy-like and not authentic enough. But at the same time, Airfix was changing its sales strategy. It had built a huge business on the basis of merchandising salesmen going round in their Ford Cortina Mk2 estates full of loads of boxes packed with kits. They called at corner shops that sold a little bit of toy product, a little bit of confectionery and perhaps a little bit of haberdashery, saying, “Hello, Mr Brown, what can I get you today? How many Spitfires would you like?” And they would dress the rotary stands. As time went on it was decided to move away from this sort of very cottage industry approach and go for block sales. So it instead became, “If you want to buy kits, fine, but you’ve got to buy a box of twelve Messerschmitts or twelve Hurricanes,” or whatever. This ran contrary to the way corner shops operated, which was selling the pocket money toys and gifts – spontaneous purchases. So some of the small retailers got together, forming consortiums where one would buy the Spitfires, one would buy the Messerschmitts, etc., and they would split their boxes up, do mix and match and be happy. Airfix was going for volume, turning its back on its seed corn and only selling to the big brands like Woolworth’s or giant conglomerates like GUS,’ said Graham. (Great Universal Stores was the massive catalogue mail order combine that was also engaged in retailing, manufacturing, financial services, property investment and travel.)

Airfix/Bachmann fighting pair: Me109 and Spitfire.

‘Come November time, pre-Christmas, it was like royalty was turning up,’ said Sue. ‘“The big buyers are coming”, “Be on your best behaviour”, “Make sure the showroom is dressed properly!” that sort of thing!’

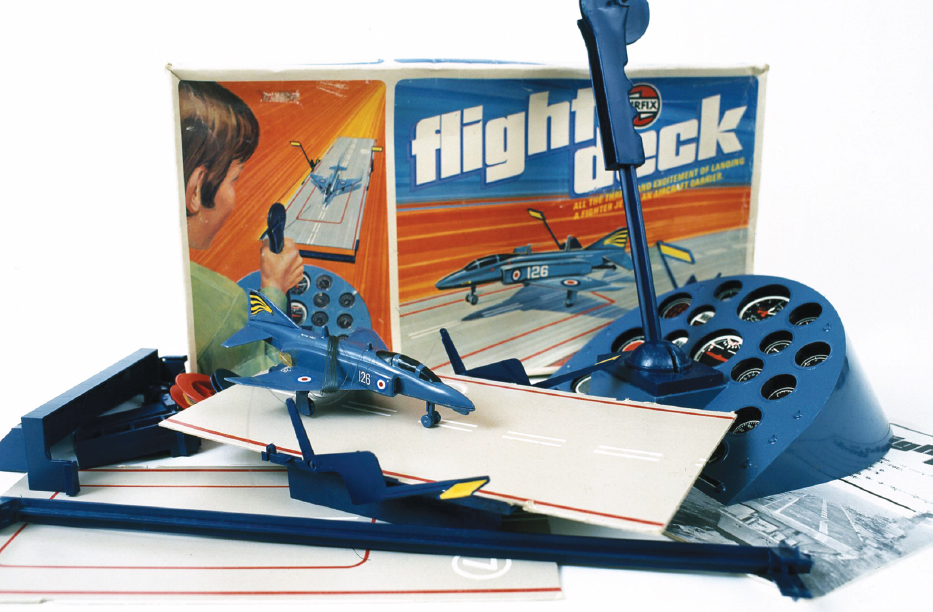

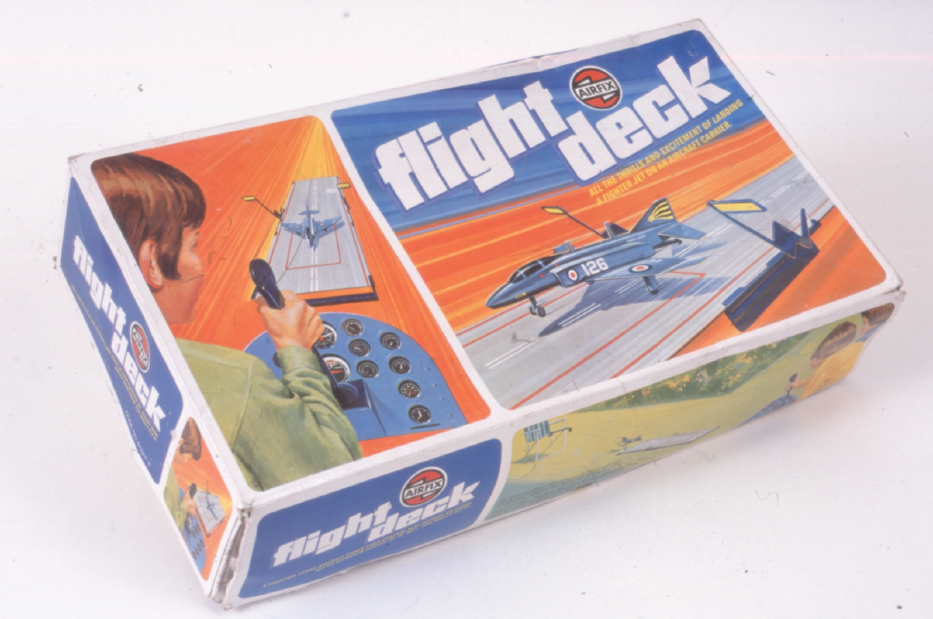

Graham told me that Flight Deck, though a great seller with a good TV commercial, was ‘a poor performer’. It seems James May isn’t alone in arguing that all-weather fast jet deck landings onto the pitching deck of a Royal Navy carrier can’t really be accurately simulated by guiding a plastic Phantom F4K onto a 3ft length of plastic while it dangles from a length of cotton!

‘So many ideas that came out of development at Airfix, such as Super Hovercraft and Supercopter, were ahead of their time, but limited by the available battery technology,’ said Graham. Enthusiasts will recall that Supercopter, which, for the record, was invented by one Mike Payne, was a ready-made yellow toy helicopter with twin rotors, but was fixed to a counterbalanced thin tubular shaft and then attached to a central revolving pivot. Although the user could make it rise or fall and go forwards or backwards via joy stick, it was still tethered. Graham told me that hours were spent trying to see if it could fly by wire. Similar limitations meant that because Super Hovercraft developed insufficient lift to carry the heavy batteries used at the time, its operator had to follow closely behind it carrying a control box joined to the machine by a trailing power cord! ‘If you chose to use it on water, for example,’ said Graham, ‘you would have to wade along behind it!’

The window of this 1970s’ hobby shop was an Airfix sales manager’s dream; absolutely jam-packed with the full range of Airfix Arts & Crafts items. ‘You’d kill for that kind of exposure,’ said Graham Westoll. ‘In the old days, Airfix would never have been able to occupy, exclusively, a complete window in a hobby store with only its arts and crafts products. But this is what we achieved, based on what Mary had started, and some sales manager somewhere managed to convince a store manager to display the entire range.’ So proud were they of this achievement that Sue Godfrey told me that Airfix actually featured a much larger copy of this print on their toy fair stand.

Graham told me that the Airfix development team took apart Polaroid instant film packs in an effort to see if the slim batteries used within would be applicable to the hovercraft. These were found to be totally unsuitable because of their very short battery life and relative expense. I’ll look at the fabled Airfix Hovercraft in more detail in a few pages’ time.

Two boys playing with Flight Deck. Based on a US patent, in 1973 Airfix released their new game, which perhaps promised more than it delivered, coming about as close to the reality of landing a Phantom jet fighter onto the pitching deck of an aircraft carrier as paint ball is to military combat. Nevertheless, the toy sold by the bucket load and was trumped in 1975 by Super Flight Deck, which, despite containing a yellow F4 Phantom, offered enhancements such as a more realistic carrier deck, a power launcher, and the ability to send the jet shooting along the line after take-off, and then, as gravity took over, perform a 180° turn before it attempted to land back on deck. (From the V&A Museum of Childhood archive. Copyright Airfix)

Graham said that one very practical technical development pioneered by Airfix was the use of soudronic, or ultrasonic welding of components. This process utilized a controlled sound pulse to make the contact points between three or four pieces of plastic flow and fuse. ‘It was glue-free and incredibly robust. Effectively, the plastic became synergistic,’ he said.

This technique enabled Airfix to neatly and permanently fuse together the various different coloured plastic components of individual Weebles, such as hair piece, body piece and base, plus the internal weight, without the use of an adhesive. ‘In the early development stage of the Airfix Weeble, after the soudronic test work had been done, we than had to find out how durable the toys were,’ said Graham.

‘We were on the second floor and there was a zigzag flight of concrete stairs leading from our department to a fire exit. I remember going out there with Jim and a few others and throwing the Weebles down a flight of steps to see how far they would travel before they shattered. They were tested to destruction, not using science, but using brute force! And I think it was because we were one of the first to use soudronic welding that the Weebles were so robust. You simply couldn’t break them.’

Mint and boxed Flight Deck toy.

Graham told me that although his and Sue’s Arts & Crafts Division was operationally quite distinct from Toys & Games, those involved with Flight Deck, Zero Lift-Off, Data Cars and Airfix Eagles, for example, such as Mark Hesketh and Jim Dinsdale, actually sat in close proximity. Consequently, whenever Jim was working on Weebles or Eagles, Graham couldn’t help noticing what was going on. ‘We weren’t in boxes,’ he told me. ‘We could hear each other talking, so if Sue and I were having a row about something Jim would hide under his desk in case the shrapnel came his way!’

Returning to the area of buying and budgeting, Graham and Sue told me that although they had a pretty free hand, they were encouraged to find material that had a multiple use, such as felt or raffia paper. ‘Looking back,’ said Sue, ‘one thing that amazes me is the size of the individual component parts in Craft Kits. You were including bags of pins and sequins and nowhere on the packaging were the warnings ‘Not suitable for children under the age of three’ or ‘May contain small parts’.’

Airfix Data Car – a big development from the previous Datamatic car. This version could really be programmed!

I asked Sue if she got involved with each stage of the product cycle.

‘Oh yes, we did everything. We would make up the prototypes, take them along to the photographer and manage the models. Everything. We used to use a photographer called Norman Hardy, whose studio was part of an old church hall in Worcester Park. It used to amaze me that it would take so long to get photography done. However, one of Mary’s little gems was the soft toy range. And around the time of the Birds Eye Peas ad we actually used Patsy Kensit as a model because Mary had seen it and said she wanted to use the same child!’

So, although I doubt it would enjoy the prominence of Absolute Beginners, Lethal Weapon 2, Emmerdale and Holby City on Ms Kensit’s résumé, if she so chooses she could add 1974’s 5th edition Airfix Arts & Crafts catalogue to her CV. For there, on page twenty-eight, the young Patsy (the catalogue was compiled in 1973, when she would have been five years old) can be seen cuddling Pink Kitten, one of Mary Wright’s brand new Soft Toy Kit range. The catalogue read: ‘Pack contains pre-shaped foam parts for stuffing, stretch towelling, felt, needle, cotton, pattern sheet and full instructions.’ The contents presented, the blurb assured readers, ‘a kit with which to make a soft toy, but in a special way. …’ But whether it would be possible for young customers to construct a Blue Bunny or a Teddy Bear as expertly as the plush Pink Kitten nestling against the comely Patsy Kensit’s cheek, one can only guess.

Sue told me that nearly everything shown in Airfix catalogues was a prototype. ‘We worked very much to a twelve-month cycle. Everything was geared towards toy fairs and the pre-toy fair shows,’ she said.

‘We lived one year ahead,’ Graham added. ‘We would do a toy fair, say in 1978, and as soon as it was over we were working on 1979’s products.’

Sue confirmed the relentless, almost Groundhog Day routine. ‘About a month after the toy fair it would be sample making, because buyers would want a lot of samples of what took their eye at the toy fair, and then come March/April time [the annual British Toy Fair is held in January] we’d start looking for new ideas and we would develop them through the early part of the summer, but come August/September, you would have to get all your costings right and then have time to get the prototypes ready for November. You would then get the feedback from the big stores about whether they liked our proposals but if they had a bit of a “no-no” about it, it would get dropped. On the whole, however, we used to get the new products pushed through pretty easily. We had two or three board meetings where the ideas were presented as we sat around the table waiting for a yes or no.’

‘It was a very intuitive process,’ added Graham. ‘It was a bit like the time of Mitchell and the Spitfire – “if it looks good it will fly good”. There was a lot of that … as long as the price was right!’

Graham couldn’t help stressing the hands-on nature of working at Airfix at the time and the amount of responsibility conferred on relatively young shoulders. ‘Compared to how things are now, back then we had far closer involvement and saw the product develop all the way through.’

Peter Allen, who worked in the Kit Division upstairs from Graham, agrees that the amount of trust given by Airfix and the maturity they expected without miring the process of design with numerous protocols or mandatory procedures, was one of the joys of working for the company back in the day.

Sue Godfrey also confirmed that Airfix staff were multi-tasking before the phrase was in common parlance. ‘We were even making the prototypes, the samples,’ she said. ‘Because the reps would come in and they would want samples sent out, we had to paint the Painting by Numbers pictures three or four times over. The toy and hobby shops would also want samples to put on display and we would do them too. In fact, at one point we had a little team of out-workers who would frantically help us paint the Painting by Numbers pictures. Sometimes we would do one where the bottom corner was left unfinished so you could see how they were completed. Before and after, so to speak.’

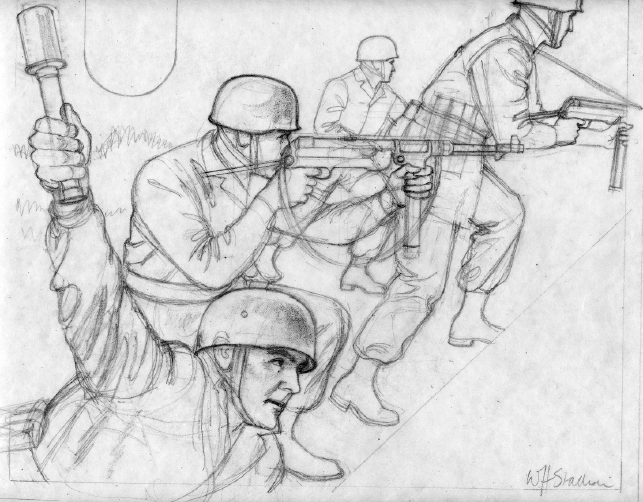

Graham went into a bit more detail about how the team managed to convert a continuous tone full-colour masterpiece by a legendary artist such as Roy Cross, for example, into a patchwork of individually numbered areas, which, if things worked out right, would blend together when seen from a distance in the same way as the lithographic dots on a printed page merge to create the illusion of a single image.

‘As far as the process was concerned, you would take a picture, like for example when I converted Roy Cross’s beautiful pictures of the Santa Maria and the May Flower and … proceed to reduce the artist’s complexity to no more than thirty-eight distinct colours!’ he said. ‘First you made that conversion. And, it being pre-computer, you put a piece of art cel over the top of the original, and traced around every single area with a Rotring pen, allocating a number to each. That stage would then be photographically copied, not scanned, in front of a bloody great camera, to be produced as a proof. You then tested it. So you’ve got the colours, based on the numbers you’ve suggested, and you could then recreate the picture again.

‘Converting Roy Cross’s paintings to the Painting by Numbers format was a wonderful task,’ he said. ‘It was very humbling because I was given access to his original art, not a print.’

Graham told me that it was easier for him to concentrate if he did this precise kind of work at home, there being too many distractions in the office.

‘You had a thirty-eight-colour palette. You would have so many greys, so many flesh tones, and so many browns. You knew what colours you had to play with and you knew what graduations you hoped to achieve. Nowadays, of course, you can buy computer software that will do the job for you. But back then I would just do it and if it looked right, then great; if it looked too “contrasty”, I would have to do a little reworking. Once I felt the painting looked OK and I was sure I hadn’t used more than thirty-eight allotted colours, I would place a sheet over the top and begin to start tracing individual colour divisions coded to individual paint tubs.’

Although Graham worked on several of the legendary artist’s paintings, he never actually met Roy Cross. ‘Roy was the property of Jack Armitage, who had a ring fence around the artist! But I was allowed to have access to Roy’s artwork and take them home at night. I was trained as a graphic illustrator and my favourite artists included the Beggerstaff Brothers [celebrated British illustrators and posterists William Nicholson and James Pryde] and the pre-war German poster artist Ludwig Hohlwein. When I was at college I studied the way they broke up large areas of graduated tone and form into solid colours.’

‘We would spend a couple of months just key-lining, painting and testing these pictures,’ recalled Sue.

‘And then you would have to produce the final artwork but would have to prepare a prototype, prepare box art and any presentation material required,’ Graham chipped in. ‘But then, even when, finally, the printed item arrived, you had to paint it again to make sure it was right.’

Because the paintings were originally designed in the US and simply shipped over to London and rebadged by Airfix, the initial Painting by Numbers pictures didn’t have a lot of domestic appeal.

‘We wanted to do something a bit more British,’ said Sue. ‘We started to source British artists who could paint the pictures we wanted and we soon found our “golden boy”, Geoff Page, the artist behind many of the Airfix Painting by Numbers, most of which featured equine subjects.’

‘His Black Beauty was not a patch on his Red Rum, though,’ Graham laughed.

‘I think in each size range we released two or three new subjects every year. We also developed new ranges,’ said Sue.

In fact, one of the ranges introduced during Sue and Graham’s time at Airfix was the New Artist Easy Paint Plus assortment, which featured quickdrying acrylic paint and humorous subjects such as Playful Fawns, Foxy Fun and Clown Capers.

‘Reeves had introduced acrylic paints for the artist and they were ideal,’ said Graham. ‘They didn’t stick to the carpet, they weren’t messy – they were ideal for children. The fact that you could now produce Painting by Numbers paints that were water soluble, easy to use and quick-drying to boot, was a real advantage.’

Graham and Sue were also involved in some of the early experiments to prevent acrylic paint ‘sissing’, meaning not sticking to the pre-inked ink outlines of the coloured areas on Painting by Numbers pictures. Paint was repelled because of the confluence of synthetic colour onto a base board featuring lots of equally synthetic detail. One of the biggest problems with Painting by Numbers sets for children who wanted to avoid an unsightly finish was the problem of painting over the even thicker black-inked lines demarcating each colour on their simpler masterpieces.

Today the paint industry has mastered all these problems and, as Graham says, ‘today you can even apply acrylic to glass.’ It wasn’t so easy in the 1970s.

Back then, Graham even recalls being involved in some of the early development work that led to the now familiar acrylic paints being used directly onto polystyrene models. In the days when modellers of my generation almost exclusively used Humbrol enamels (Airfix magazine even recommended these above Airfix’s own brand!) such possibilities were but a pipe dream. Actually, Graham recalls Airfix chemists seeing if the addition of ethylene glycol as an ingredient of acrylic paint would help them adhere. Few today can ever appreciate the difficulties we Baby Boomer plastic modellers faced, even with enamel paint, to get an even coat on a just-built plastic kit. Why, we even had to follow the advice of more experienced modellers about washing our prizes in ‘Squeezy’ in order to remove the oily mould release agent from our naked models, if we ever hoped to get a perfect finish!

Although the two divisions were never administratively combined, in 1979, for cost reasons, Airfix combined Toys & Games and Arts & Crafts in a single catalogue. Despite the recent budgetary restrictions, in this publication Airfix claimed that ‘Greater sums than ever before are being committed to advertising campaigns … each of the major toys from Airfix is backed by substantial marketing support.’ £300,000 was committed to Airfix’s four largest brands – Micronauts, Weebles, Super Toys and Games.

It was about this time that Sue and Graham, to use Sue’s words, ‘went to town’ thinking up their own ideas. ‘Oh, we’d gone native,’ said Graham. ‘The ideas that nearly went to market but didn’t, but the fun we had proving that they might! Such as Straw Pictures – do you remember that time we went out into the country to get the straw?’

‘There were Mirror Signs,’ Sue interrupted. ‘It was very fashionable at that time to have these kinds of pub mirrors with all kinds of pictures on them. We sourced a non-breakable mirror foil from ICI, onto which we applied paint and little plastic crystals, and used them in our New Artist Mirror Signs.’

Graham pointed out that he and Sue were also involved in creating bespoke packaging variants for Germany. These were usually confined to simple tipons, bearing translations and market specific information for German importer Plasty, the then West German Bundesrepublik Deutschland prohibiting imported goods that didn’t feature German translations.

‘The bottom end of our market was, I suppose, children aged around five years old right up to retired people who would tackle The Mona Lisa,’ Graham added.

I asked how much involvement Sue and Graham had with the catalogues. They told me that although the assembly and production was managed by Grey Advertising, Airfix’s creative and media agency, likewise an external consultancy, Artbeat, produced the design and artwork for all Arts & Crafts boxes. ‘We would tell them what we wanted though,’ said Sue.

Graham told me that one of the things the duo did was take the junior range and give it its own identity. Similarly with the senior range, they were concerned that it looked elegant and up-market for more discriminating adults.

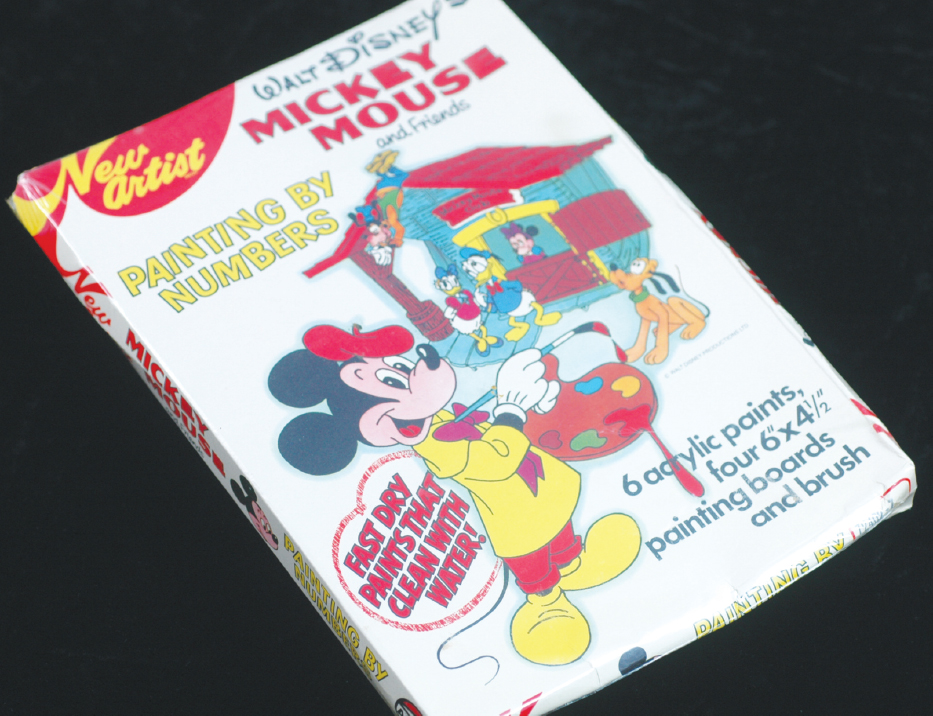

In fact, the new packaging was trumpeted in the 1979 catalogue. ‘The New Artist packaging is warm and vibrant with colour,’ boasted the blurb. ‘Each series style clearly indicates the intended consumer. The bright yellow of Easy Paint, Easy Paint Plus and Easy Oils group these products together and provide a bold colourful display for you in-store, whilst the daubing style of writing clearly indicates the products are aimed at the younger child. The more sophisticated style of the Studio, Collectors and Velvet series complements the products, which are aimed more towards the older child. The fun image of character merchandised products, such as Disney’s Famous Films and the Mickey Mouse series, add to the exciting display you can create with these products.’

The latter range presented a real treat for Sue, a lifelong Mickey Mouse fan. ‘I remember doing the drawings for Mickey Mouse, which I had to then take up to Disney for their approval.’ Apparently, Disney kicked up quite a fuss about the line thickness of Sue’s interpretation of the world-famous cartoon rodent.

‘I went up there with all the artwork and I saw a chap up there called Keith Bales and he was great. He said, “Do you want a job?” The biggest mistake of my life was saying no,’ Sue lamented. ‘But I’d only been back at Airfix for a few months and felt I should turn it down. But there you go. That is my claim to fame with Mickey Mouse!’

In fact, Sue reckons working on the Mickey Mouse products was the highlight of her time at Airfix – although she was keen to stress that, in fact, ‘it was all fun!’

Graham remembered that in parallel with the existing licence with Disney, Airfix were also regularly offered new licences by those rights owners keen to be included within the product range. ‘The BBC would have a licensing day each year. They would offer a range of products for licensing, talking about next year’s schedules and what new programmes were going to be broadcast and which existing properties were going to return to the screen.’

Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse by Airfix New Artist Painting by Numbers. Mickey fan Sue Godfrey was the driving force behind this.

Sue recalled that Airfix secured the jewel in the crown, Dr Who, in 1977, when she and Graham were at the helm. She told me that Geoff Page, he of Red Rum fame, returned to illustrate the New Artist commissions of Daleks and Cybermen. Airfix would have enjoyed an exclusive licence for any Dr Who Painting by Numbers products.

However, such a commercial coup could prove costly because, as was the case with Dr Who when star Tom Baker moved on shortly after the licence was agreed, Airfix were left high and dry and in possession of a painting of a Doctor who was no longer on TV.

Similarly, Airfix secured the licence for London Weekend Television’s children’s drama Dick Turpin, featuring Richard O’Sullivan fresh from his huge TV success playing Lothario Robin Tripp in Man About the House and Robin’s Nest.

This time Graham produced the original paintings. ‘One featured a dramatic setting sun, gallows with musket,’ he said. ‘The other showed Dick Turpin on a horse. Again the packaging was designed in our new style with bold imagery, strong typeface and copy explaining about Richard O’Sullivan starring as Dick Turpin and encouraging purchasers to “capture again the magnificent days of the dashing highwayman”, that sort of thing.’

Like the previous paintings it had to be ‘blessed’. ‘I’m not sure if Tom Baker approved his portrait but certainly the Dr Who licence holder would have. However, Richard O’Sullivan had to ‘bless’ anything using his image,’ recalled Graham, who had to take his two paintings for the actor’s approval at the TV studio.

‘He thought they were great,’ smiled Graham. ‘He signed them off and actually asked to keep them!’ However, as they were the only originals and Graham had yet to trace them with his trusty Rotring ink pen, he was forced to take them back to Haldane Place. He told me he did send Mr O’Sullivan the pen drawings though.

Sue said that after the new packaging she and Graham had supervised was launched at the 1979 Toy Fair sales of New Artist products increased by ‘leaps and bounds’. I was particularly interested to know how closely the duo were involved in the Picture Kits, the paintings comprising seemingly rather disparate runners taken from obsolete Airfix kits.

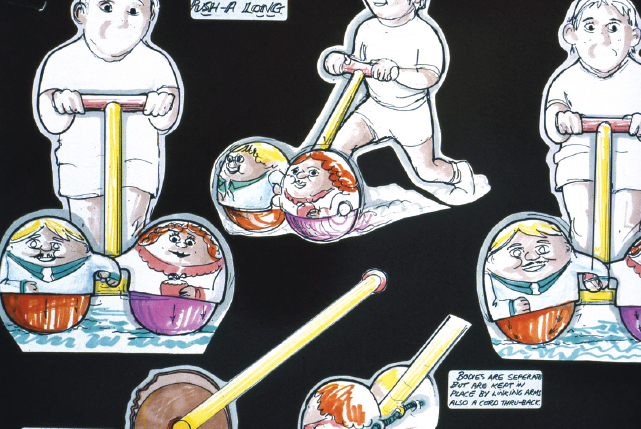

‘Only six made market, but they were an attempt to satisfy the pocket money market. Launched in London’s Holland Park, the conservationist focus of Nature Trail was ahead of its time.

‘Back in 1977, environmental issues had started to come into public awareness,’ said Graham. ‘Responding to this and to bring an educational angle to Arts & Crafts we developed the Nature Trail range. These kits were designed to have a Natural History Museum feel with a pre-printed, cut-out diorama, foreground figures and black and white cameos of the creatures to be found in the environment illustrated (three scenes were featured: Countryside, Seashore and Town & Garden). Watercolour paints were included for the kids to colour the cameos with, based on their own observations. An informative set of fact sheets were also included, plus a copy of The Country Code.

A rare crossover between the Arts & Crafts and Kits divisions, Picture Kits combined components from obsolete construction kits with the familiar frames used in other ranges, such as Cotton Craft.

‘The illustrative work was done by two very talented guys, David Ashby, who was a leading illustrator for Dorling Kindersley, and an old college mate of mine, Paul Adams, the chap who created the illustration of a ginger cat that was featured on tins of Whiskas for many years.

‘The kits were produced in association with the then World Wildlife Fund and had a PR launch at Holland Park Gardens. It was proposed to have Spike Milligan as the celebrity guest at the event – he being, at that time, a leading nature campaigner. Unfortunately, due to his rather unpredictable personality, Airfix’s PR agency was asked to take out insurance against the possibility of a ‘no show’ by the father of The Goons. The cost of this was regarded as too high so it was suggested we should get David Bellamy instead, to “wummage awound” at the launch. Again, budgets did not fit so I think the launch featured John Gray and some chap from WWF [name unknown].’

The Nature Trail kits fitted very well into Airfix’s corporate profile (educational, technically accurate and of more value than just a trivial toy). The kits were very popular and were sold to a number of educational authorities and appeared on the shelves of WWF associated visitor attractions and the Natural History Museum.

I asked Graham and Sue if they were involved with Fimbles, one of Airfix’s most forgettable Arts & Crafts creations.

‘They originated from a little old lady somewhere down in Devon or Dorset,’ Sue told me. Sue reckoned that probably her all-time favourite product to work on was the series of New Artist Pin Pictures, which enabled customers to create works of art by sticking pins into the outline of a particular illustration, such as a church, traced in velvet applied over expanded polystyrene.

‘They were fun to develop. They featured sequins; they were glittery and easy to do.’ Sue reckoned they were a very in vogue product in the 1970s and I certainly remember going into quite a few homes then with framed pictures of scenes fashioned in pins, nails and coloured threads proudly displayed on living room walls.

I wondered if Graham and Sue had much to do with the much larger Kit Division upstairs at Haldane Place.

‘No, I don’t think so,’ said Sue. ‘I think they thought we were a bit weird; we were totally, totally separate. I could probably count on the fingers of one hand the number of times I went up to the Kit Department. Our paths never crossed.’

However, Graham told me that one occasion when they did work together was during the time Airfix was experimenting with acrylic paints to put into Painting by Numbers sets and to develop as an alternative to enamels for kits.

‘I did a lot of trialling work because obviously we had the paints. So, Jack Armitage or Peter Allen would come down because they were looking at putting child-friendly paints into starter kits. But when they tried painting Queen Elizabeth, for example, with the paints we put into the Painting by Numbers sets, the model didn’t look any good. But then we found out that if you washed it with Fairy Liquid it would adhere. But, of course, it was crazy to have “before painting, immerse model into washing-up bowl,” so we didn’t get much further.’

Graham told me that during the four days of the toy fair, Airfix reps stood on a big stand enduring an endless looped tape of Fimbles are Fabulous on one side and Weebles wobble but they don’t fall down on the other.

Eventually, hard-bitten reps, normally so difficult to impress and often so dismissive of Arts & Crafts lines, which they found more difficult to sell than traditional ‘war toys’, began to eagerly await each new release from Airfix’s arguably most creative department. Graham said that he and Sue began to change attitudes, adding that sales reps, dependent on commissions to boost their incomes, eventually realized that each new series of Arts & Crafts products might add to their bonuses.

‘Reps would actually come up to me after sales conferences and eagerly ask, “What have you got for me in the Arts & Crafts line for next year?” – a real turnaround,’ Graham recalled. ‘There were a number of occasions when the guys on the 3rd floor came down to Arts & Crafts for input where a touch of ‘artiness’ was needed. Typical of this was when Airfix acquired Meccano Dinky.

‘Having taken on the rather out of date Dinky range it was decided to breathe some new life into it with makeovers to selected cars such as the Volvo estate, which I redesigned as a motorway police car. This, and other similar exercises, went no further than basic prototypes (great fun to do, though). As far as I’m aware, none of these ideas were ever implemented as the only change being made to the range was a rebranding of the packaging. This involved extensive research into consumer response to colour – people didn’t like green but trusted blue – which led to a new look for the Dinky range even if it was only related to the packaging.’

Similarly, when it was decided to bring out a couple of sci-fi models, including a star fighter, Graham was asked to design the decals, including creating markings in an alien typeface.

Another area where Arts & Crafts was asked to help the Kit Department involved a project to provide kit makers with water-based paints that could be included in the kits without any attendant health and safety risks. ‘As for several years we in Arts & Crafts had been using water-based paints, it was natural for the guys on the third floor to come downstairs and have a chat with us,’ said Graham. ‘We were given a number of kits to play with including the recently introduced Queens of England figure series – which needed painting for the catalogue as well as for instructional use to demonstrate how well our paints would work on the actual kits.’

Unfortunately, due to the fact the kits had a light coating of release agent, employed to get them out of the mould, the paints would not stick! Before the paint could even start drying it began to siss. Instead of covering the surface smoothly it merely collected in globules of coloured water.

‘It was a case of the idea coming before the technology,’ laughed Graham.

Various solutions were tried, including the addition of glycol into the paint to act as an extender, but this would have meant a unique production line of paints, something the company wanted to avoid so as to keep production costs down.

Sue and Graham were always looking for new ideas to add to the range and, at the same time, make the most of existing material.

‘Even in those days penny management was very much the watchword,’ said Graham.

Back in the mid to late 1970s, pictures made out of clock parts – images featuring subjects like the Tower of London, Big Ben and Buckingham Palace – were all the rage and very popular items in gift and souvenir shops.

Graham had an idea of how Airfix could capitalize on the fashion for 3-D pictures simply by using the numerous plastic mouldings they already had by the thousand in the firm’s parts store.

‘We had already got a well-established range of pin and sequinned basic pictures that utilized a flock sheet on a polystyrene base. And, of course, downstairs, in the moulding shops, we were up to our necks in pieces of kits. So I came up with the idea of combining these already available raw materials to do our own version of these clock part pictures.

‘Selecting parts from common moulds, I designed a range of pictures, which painted with silver or gold acrylic paint and with bits of white cord could be assembled into images of a steamship, traction engine, airship etc. The base for these was formed from a sheet of black flock paper and one of the ubiquitous polystyrene tablets from the pin pictures. It was another of those “making something out of what we had lying around” moments and creating a product that reflected a current trend!’ he said.

There was quite a lot of cross-department working within Product Development. Graham told me that this was particularly so when it came to evaluating new games ideas. Inevitably most games required a minimum of two players, sometimes as many as six, so it was all hands to the pump.

‘It was great fun, as ever, being paid to play with toys and games. Some of the ideas came to us from other companies or what I would call semiprofessional games developers but also from members of the public who had come up with something for their family to play, and thought they had the next Monopoly or Scrabble.’

One day in the Arts & Crafts office the team had the radio on, tuned to LBC, the London Broadcasting Company, Britain’s first legal commercial independent local radio station, which began broadcasting in 1973. The subject of discussion of this phone-in was the lack of investment British industry made regarding home-grown ideas. Apparently, one contributor hammered on about how he had come up with a wonderful board game, which, he claimed, he had submitted to several British toy companies and had had it returned ‘without the box even being opened!’

‘In what turned out to be a moment of madness, I called the station to reassure them that the toy company I worked for always fully evaluated any ideas submitted to them,’ said Graham. ‘The presenter was very impressed and asked me if I would like to name the company. Thinking I might earn a few brownie points I told him that I worked for Airfix.

‘Oh dear! What a mistake! About an hour later I started getting calls from reception to tell me that somebody had turned up asking to speak to Graham because they’ve got a wonderful games idea that they wanted me to look at. This went on for the next two to three days and I was presented with everything from the sad to the mad to the ridiculous!’

Many of these games ideas featured Airfix HO-OO scale polythene figures but there were also some that obviously had their origins in far-off lands involving bones, twigs and even a variety of gourds.

‘Having made this cross for my own back I got thoroughly nailed to it by my colleagues who thought it was great that my attempt to get a bit of free publicity for Airfix had backfired so badly.’

As with so many home-grown ideas, Graham told me that most of these games had no conclusion and would simply be played forever, getting nowhere. They were also so convoluted they required a degree in applied mathematics to play. Many were just too complex to be manufactured. Regardless of their practicality or even downright play value, Graham said that each idea came with the inevitable assurance that ‘my family and friends think this game is brilliant and they love playing it.’

‘The lesson is simple,’ said Graham. ‘Never give out personal details to a phone-in programme!’

When Airfix decided that a brighter, more child-friendly style of packaging should be used for some of the new Painting by Numbers sets they approached an agency called Artbeat, who, working with Sue and Graham, helped deliver the bright new look. Graham created a character called Little Arty.

‘He was a cheeky cartoon fellow with ginger hair, and oversize artist’s beret, leaning on oversize paintbrush with a big puddle of paint.’

Graham and Sue also introduced a more appropriate style to the senior ranges and for the recent pictures they had introduced, including the Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost and the Royal Scot. A new box style with a more classic style was also introduced.

The story of the slick deal George Lucas cut, enabling him to retain the toy merchandising rights to Star Wars, has become part of modern folklore. What perhaps isn’t as well appreciated is the fact that the kind of now ubiquitous small 3ins action figures that resulted revolutionized the toy industry and sounded the death knell for larger, 12ins figures like Action Man and GI Joe.

‘Quite soon after this dynamic development of the market, we started to hear rumours that Palitoy was planning to produce a miniature version of Action Man. As the leading producer of HO-OO, 1:32 and 1:48 scale soldier figures it was logical that Airfix would also look to enter this market sector with their own offering,’ said Graham.

Airfix Eagles were the result, which, as is mentioned elsewhere in this narrative, were largely based on German company Plasty’s Action Hero range. However, two home-grown elements of the Eagles range were a control centre (‘based on what looked like a piece of Marley plumbing pipe,’ said Graham) and also the fearsome Capture Copter. ‘These were both designed by Wynne Thomas, a designer/stylist who had previously worked on the interior design of the Mini Metro for British Leyland.’

To support the launch Greys Advertising produced a number of fullpage adverts, again adventure themed, which appeared in leading boys’ comics. Graham’s not sure how successful this campaign actually was but said, ‘We had lots of fun writing alternative play scenarios and finding imaginative (if possibly illegal) poses for the figures.’

The last toy fair Sue and Graham jointly worked on was in 1980. Sue explained that she had been working on the ‘same cycle’ for quite a long time and asked to join the Marketing Department for a change and to do something different.

‘The problem I was having personally in product development,’ said Sue, ‘was that marketing were stepping in and taking over. It caused us problems because we weren’t allowed to be quite as creative, which had far too much impact. So I thought, “If you can’t beat them, you might as well join them.”’

Wynn Thomas, the stylist on Airfix Eagles. Ex-British Leyland, he designed the Capture Copter with the large grabbing claws protruding from its nose. This was known as the Vario Copter in Germany, where importer Plasty also renamed the Eagles, ‘Action Stars’. Wynn designed several other things for the Airfix Eagles range.

Graham added that at the time the big growth in the field of marketing was in the area of consumer non-durables, particularly in the comestibles. ‘If you want a really good marketing person – go to United Biscuits. They were the great innovators who could rebrand and reduce the size and quantity of ingredients in a biscuit, give it a new wrapper and encourage people to buy it. Within a period of only a few months about four people came from United Biscuits and although they had no experience of the toy market whatsoever, they started telling us what to do.’

Soon after the 1980 toy fair Sue left the Arts & Crafts Division and joined the swelling ranks of FMCG (fast moving consumable goods) executives who had joined Airfix. ‘However, I soon realized that it wasn’t a very good thing to have done,’ she said, and quickly left Airfix to join MB (Milton Bradley), one of the world’s largest toy and games makers.

She originally applied for an art director’s position with MB but actually ended up managing the design and production of the company’s catalogues. A year after joining MB Sue gave birth to her son Tom and left. She never rejoined the toy industry, instead freelancing from home for the next fifteen years. Ironically, her freelance career was prompted by ArtCraft, who supplied some of the paint used in Airfix’s Painting by Numbers sets, and who asked Sue if she would undertake some freelance work for them. It being convenient to work from home with a son at school, Sue’s freelance work spiralled from there.

Once Tom had got to the age of about fifteen, Sue joined Janes, the world famous publisher. To demonstrate what a small world it really is, when Sue was with Janes she worked alongside Mike Gething, the last editor of Airfix magazine, whom I had the pleasure of interviewing for my 1999 history of Airfix model kits (Airfix – Celebrating 50 Years of the Greatest Kits in the World).

Things really began to change after what Graham calls ‘the biscuit boys’ joined Airfix. He is adamant that the techniques used to increase or decrease the quantity of chocolate in a biscuit, or pack more or less biscuits into a packet to capture a price point, weren’t applicable to kits, toys, arts and crafts. He reminded me of the disastrous decision of the early 1980s that led to the revisions in Airfix packaging resulting in boxes getting bigger and more expensive as they jumped up a series category or two, whilst the contents remained the same as before the revamp. Modellers felt they were suddenly paying more without getting anything new. He reminded me of one quip going around the industry in those days that Airfix kits were more air than fix … He also derided the company’s decision, at the advice of its new marketing executives, to employ dozens of external and very expensive consultants, who allegedly often proposed solutions Sue and he had suggested some years previously.

‘These people would be taking consultancy fees to come up with hackneyed, crap ideas that showed they knew nothing about the toy market, nothing about how children thought and nothing about our industry. We had seen it, done it, made the video, written the book – nothing was original. They would then turn to internal resources, speaking to people like me and Jim Dinsdale in Toys & Games, about things such as action figures.

‘We were coming up with ideas based in a legendary time, a land where the powers of magic and the powers of science come together to fight an eternal war with sword and mystic magic. … All that kind of stuff; completely blue sky sort of thinking. However, we had a very conservative board. “It’s not a Spitfire, is it?” “Did the Luftwaffe ever use them?” and “It’s not really Airfix, is it?” That sort of reaction.

‘A couple of years later, Mattel brought out He Man! Again, in America, Micronauts were huge, being chiefly known via the Marvel comics. Airfix brought in the product but never actually developed or extended it so that it met the needs of sci-fi buffs like the range did when available in America.’

After leaving Airfix Graham jumped from client to supplier, joining advertising agency Foote Cone Belding (now part of the Interpublic Group, which brought it together with Draft in 2006 to become Draftfcb), where he worked on below-the-line accounts for a couple of years. Ironically, about six months after he joined FCB, Graham became involved with the Palitoy account, the company who in little more than a year would assume operational control of Airfix. Graham was involved in the introduction of Palitoy’s 3.5ins Star Wars figures into Europe as well as the multi-national relaunch of Mattel’s Hot Wheels.

After being head-hunted by another agency Graham decided to strike out on his own, establishing Broadsword, his own marketing agency.

Jim Dinsdale joined Airfix Toys & Games in the summer of 1975 from his former job with the product design unit of British Industrial Plastics in Birmingham. ‘I studied product design but, funnily enough, although I didn’t get my degree in the end, I was the only one on my course who actually got a job!’

From college in Leicester Jim joined British Industrial Plastic’s design unit in Oldbury, in the West Midlands. Since its foundation in 1894, BIP has become a world leader in the supply of thermoset plastics and chemicals. In 1924, BIP was the first company to patent urea-formaldehyde resins, a product used in many manufacturing processes such as decorative laminates, textiles and paper, and as a wood adhesive. Indeed, it is used to bind the wood fibres in MDF (Medium Density Fibreboard).

‘It was a very unique design unit,’ recalled Jim. ‘It didn’t charge the people who used it, the people who came to them for designs. We would distribute lots of information about the various products of BIP and offer advice about which ones to use. But as far as design costs were concerned, they didn’t really pass these on. It was more of a PR thing, I suppose.’

Jim told me that he joined BIP at a time of great industrial unrest in the UK – the Three-Day Week, a desperate government measure to conserve fuel while the seemingly intractable miner’s strike continued, was instituted in January 1974. ‘Industry started chopping out various sections and design units were especially vulnerable at that time, and the unit I was in suffered as a consequence.’