3

Keeping the Species from Being Lost

INTERSPECIES ISLAND

The Jamaican landscape had been remade over decades not merely by the migration of peoples but by the transplantation of animals and plants too. The island was a battleground: Englishmen and Africans faced off for control of both terrain and species. Europeans were the accidental beneficiaries of diseases that decimated local populations as entire ecosystems proved vulnerable to catastrophic change. In Jamaica, during a famine in 1494, hungry Spanish colonizers consumed the aon – dogs that had flourished since their introduction by the Taíno centuries earlier – to extinction. After consolidating their position, the Spanish then introduced new species that profoundly altered the island’s ecology such as horses, cattle and pigs, to provide labour and food for themselves, as well as new agricultural crops from the American mainland like sugar and cacao. These changes continued in the seventeenth century as the English expanded the number of livestock pens and created ever larger plantations.1

The Columbian Exchange did not just involve interplay between Europe and the Americas, however. Africa was also a significant agent in the environmental transformation of the Atlantic world. Slaves remade Caribbean landscapes by clearing and harvesting plantation land, while plants and animals travelled west to the Americas, sometimes quite inadvertently. Guinea grass, for example, appears to have been brought over as feed for Guinea sheep on slave ships but subsequently grew wild across Jamaica, providing an important food source for the island’s livestock. Africans established their own botanical traditions in the colonies in order to survive under slavery. Planters devoted as much land as possible to growing cash crops, so set very little aside for subsistence for slaves. As a result, Africans in the West Indies were obliged to cultivate plots that came to be known as provision plantations or more fancifully as slave gardens, usually located at some distance from sugar plantations and their own dwellings, thus beyond the surveillance of most masters. Historical and archaeological research on such grounds has shown the variety of foods grown there with links to West African agriculture to include okra, maize, Guinea corn (sorghum), millet, rice, ginger, oranges, limes, coffee and beans. As Sloane observed, slaves enjoyed the ‘culture of their own plantations to feed themselves from potatos, yams, and plantanes, &c. which they plant in ground allowed them by their masters, besides a small plantain walk they have by themselves’.2

How specific plants were brought across the Atlantic is largely undocumented, although the oral traditions of more than one free black Maroon community in the northern reaches of South America tell of enslaved women who concealed rice seeds in their hair prior to the Middle Passage. A Brazilian variation claims that one such woman, ‘unable to prevent her children’s sale into slavery, laced some rice seeds in their hair so they would be able to eat after the ship reached its destination’. The story is a parable of the African origins of New World agriculture and a warning about the theft of botanical knowledge by whites: it concludes with merchants discovering the rice seeds and taking them. Despite such seizures, and though Africans and their descendants enjoyed no legal property rights in Jamaica, many planters acquiesced in slaves’ custom of willing plots of land from one generation to the next. This included both provision plantations and burial grounds. In the early nineteenth century, the Gothic novelist Cynric Williams even wrote of one slave who claimed compensation from a master who had cut off the branch of a calabash tree he regarded as his: ‘the negro maintained that his own grandfather had planted the tree, and had had a house and garden beside it, and he claimed the land as his inheritance.’3

Trees played crucial roles in Jamaican life as the struggle for control of the island played out between whites and blacks. Colonists tied slaves to trees to whip them, but trees could serve as sites of peace-making too. In 1739, for example, the leader of the Windward Maroons Cudjoe and the English colonel James Guthrie would sign a peace treaty under a cotton tree by which the British, unable to defeat the Maroons, recognized their right to exist. Some Africans believed trees harboured mischievous spirits they called Duppies, yet trees also offered refuge from pursuers and perches for casting spells against their foes. Practitioners of Obeah – and its Maroon equivalent, which Maroons called their ‘Science’ – placed talismans for protection or attack under specific tree-trunks. Trees also figured repeatedly in West African Anansi stories, which later colonists recorded in some detail. In one tale, a Maroon mother ignores a medicine man’s advice to cut down a papaya tree in order to save her daughter’s life, thinking it mere superstition, only for her daughter to die and the papaya to bear withered fruit. Around the turn of the nineteenth century, as some planters became more interested in African tales as a form of folklore, the Gothic novelist and slave owner Matthew ‘Monk’ Lewis recorded a host of such stories with animistic and supernatural resonances featuring cotton, cacao and mahogany trees.4

In Jamaica trees were no less vital to the English, albeit for the opposite reason: as commodities. Deforestation was the norm in virtually all the wooded territories Europeans colonized in the early modern era, whether in the West Indies or the East. ‘[N]othing … seems more fatally to threaten a weakning, if not a dissolution of the strength of this famous and flourishing nation’, John Evelyn had written in Sylva (1664), ‘then the sensible and notorious decay of her wooden-walls …’ Evelyn, the virtuoso and man of letters, doubled as an economic strategist in an era when Restoration planners and Royal Society naturalists backed tree-planting programmes to compensate for deforestation in England caused by shipbuilding, in order to refurbish the Royal Navy. Sloane observed that ‘the greatest part of the island of Jamaica was heretofore cover’d with woods,’ before its own partial deforestation brought about by raiding it for timber. The engravings of living trees he included in volume two of his Natural History formed a key component of his commercial inventory of the island, as he surveyed the uses of different Jamaican woods. These included juniper, used ‘for wainscoting rooms, making escritores, cabinets, &c cockroches and other vermine avoiding [its] smell’; fustic, ‘one of the commodities this island naturally affords’, ‘used by the dyers, for a yellow colour’ and ‘worth fifty shillings per tun’; Jamaican ebony, ‘for its fine greenish brown colour capable of polish … much coveted in Europe’; and the poisonous worm-proof whitewood, ‘fell’d and made into planks to sheath ships’.5

Many of Jamaica’s trees were so ‘very tall’ that Sloane ‘could not come at their leaves, flowers, or fruit’ to examine them properly. Only dextrous slaves, he conceded, could scale their summits. ‘The negroes climb’d up’ the cotton tree, for example, ‘with pegs of hard wood … the smoothness [of its trunk] not admitting other climbing’. Black mastery of the Jamaican environment was politically significant. Maroons concealed themselves in the Blue Mountains to the east and the Cockpit Country in the west, feeding themselves from the land and raiding plantations to plunder provisions. Understanding the dangers they posed, Sloane studiously avoided Maroon country on his island manoeuvres. Such places, he wrote, ‘are often very full of runaway negros, who lye in ambush to kill the whites who come within their reach’. Sloane’s use of the term ‘ambush’ suggests that he was aware of Maroons’ use of camouflage as part of a set of survival tactics colloquially known as ‘dodging’. In an oral history collected in 1978 by the anthropologist Kenneth Bilby, a Maroon descendant named David Gray described how the Windward leader Cudjoe had hidden himself in a cacao tree to attack British soldiers during the First Maroon War of the 1730s: ‘another one tek a cocoa-tree … and put it pon Kojo back, big cocoa-tree. And Kojo sit down here so. Kojo deh pon a route, like Seaman’s Valley bridge, that is a gate. When you come where him deh, and you start dead, is only big cocoa-tree you start dead from.’ In Maroon parlance, nature itself resisted colonization: the same trees the English routinely harvested could kill their aggressors. Hidden African presence was, indeed, a theme of Jamaican life. In the Afro-Caribbean Jonkonnu festival Sloane witnessed, he would have seen revellers dressed up in camouflage as a figure named Pitchy-Patchy, a Jamaican phrase meaning patchwork. In his Sketches of Character (1837), the Kingston-born artist Isaac Mendes Belisario later associated this figure with the English folk character Jack in the Green, although in all probability Pitchy-Patchy evolved from masquerade traditions brought over from West Africa.6

Animals, too, shaped the economic and social life of Jamaica. They provided crucial sources of power in the pre-industrial era: both slaves and oxen were, for example, used to turn the sugar mills that ground juice from freshly harvested cane. Although conspicuously romantic in conception and produced over a century later in the British colony of Antigua, artist William Clark’s watercolour Shipping Sugar (1824) usefully anatomizes several of the interlocking components of the sugar and slave trades. These include the oxen and horses that cart hogsheads of sugar to the coast; the slaves who roll them into longboats for transfer to ships bound for Europe; and the distant windmill that symbolizes the wind-power on which transatlantic shipping depended (Plate 2). That planters listed both their slaves and their animals together as property in inventories and wills is unsurprising, not least because whites liked to claim that slaves were animals, although Caribbean authorities also took care to separate slaves and key animals to ensure their own security. Slaves were forbidden by law, for example, from riding horses in Jamaica for fear of their mobility, but such prohibitions had symbolic functions too, since ease of mobility was a badge of white freedom; low-status whites who walked rather than rode about were tarred with the disdainful epithet ‘walking buckra’ (buckra being a black word for whites). Access to good meat was a signal white privilege. In his diary, Thomas Thistlewood recorded his enjoyment of sumptuous dinners of roast beef and plum pudding, while slaves often received impoverished rations of discards: half-rotten meat, the head or feet of animals and diseased carcasses rather than meaty rumps. Beset by malnutrition, some slaves resorted to eating soil, a practice known as geophagy or pica, a behaviour brought on as a result of psychological distress but in some instances also a strategy to stave off the stomach pains caused by iron-deficient diets and worms.7

Despite this radical inequality of access to the fuel, comfort and status prized animals could provide, blacks developed their own traditions of animal use. Many slaves lived near the livestock pens they maintained for white masters, where they carried out the work of branding and castrating bulls, while ‘hogmeat gangs’ made up of children collected grasses as fodder for these beasts. Slaves kept their own livestock in yards close to their dwellings, areas that, like provision grounds, planters tended to overlook. Sloane noticed that slaves kept their own pigs, an example as he put it of their ‘small wealth’. They traded such ‘wealth’ at Sunday markets, which became a staple of the internal economy of slavery in West Indian society. It is likely that Sloane visited such markets while in Jamaica, looking for specimens – naturalists regularly targeted markets as places to see rare species. Doctors in South Asia, for example, frequented bazaars to acquire herbs and drugs, while John Ray regularly attended fish markets in England. Later on, the Jamaica-based doctor Henry Barham would write to Sloane about visiting the ‘negro market’ in Spanish Town.8

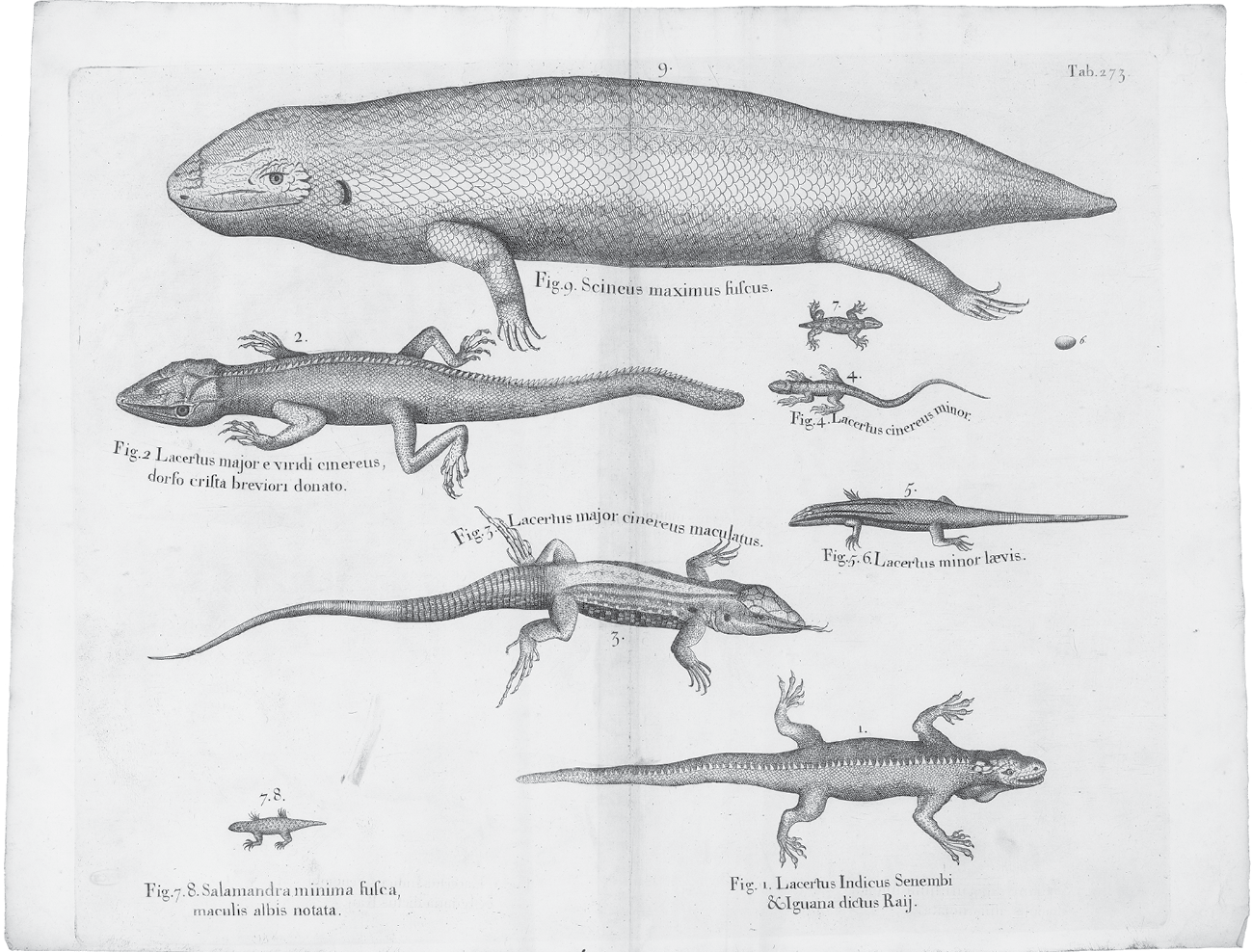

British artist William Beastall’s watercolour Negroes’ Sunday Market at Antigua (1806) visualizes the multiracial and interspecies character of Caribbean marketplaces, already well established in Sloane’s day (Plate 3). Like Clark’s Shipping Sugar, the image has a romantic quality but nonetheless illustrates English fascination with African traders and their wares. In Beastall’s tableau, blacks trade goods and produce including livestock, from hogs to chickens and eggs, attracting the attention of whites with rare specimens as well. Two dark-skinned men, wearing only trousers, emphasize the range of African access to Caribbean animals. In the centre, a man in light-blue trousers drags a hog after him, while on the far left, with the gesture of a proud hunter, a man wearing a skullcap and earring holds a reptile resembling a skink up to view. The vertical hierarchy of the scene suggests the racial hierarchy of Caribbean society, determined in no small part by access to animals: several whites ride to market on horseback, while the white officer with his back to the viewer sports a feather-topped hat that pierces the sky, making a striking contrast to the low horizontality of almost all the blacks and their creatures. Only one African stands tall: the hunter who holds up his reptilian prey and draws the curiosity of English ladies as well as black boys, suggesting the value of his prize – one of great potential interest to specimen hunters like Sloane, who ended up with several skinks in his collection.9

Slaves used their access to animals, as well as plants and objects, to invent their own cultural forms in Jamaica. They made musical instruments from country materials, while for performances like Jonkonnu they strapped cow tails to their bodies and donned ox-horn masks. Maroon fighters converted the abeng, a cow horn that planters used to summon slaves, into a horn for communication and battle. Blacks recycled common objects such as the iron strips they used both to cut cane for planters and to work their own land, as well as European gaming pieces they bought at market and used in their own games. One highly significant ritual involved the burial of their dead together with ‘grave goods’. The mathematician and traveller John Taylor, who was in Jamaica at the same time as Sloane, noted in his diary the variety of items blacks buried, which included animals: ‘casadar [cassava] bread, rosted fowles, sugar, rum, tobacco and pipes with fier to light’. In contrast to the stereotypical association of slavery and nakedness, Afro-Caribbean peoples’ natural and spiritual worlds possessed a rich vernacular material culture. To this day, Maroons still speak of the pot with a mysterious power to kill British soldiers wielded by Nanny, another fabled eighteenth-century leader of the Windward Maroons; and descendants still place a bottle of rum inside Ambush Cave near Accompong, a site they associate with the military victories over the British that culminated in the treaty of 1739.10

Obeah involved one of the most dynamic ways slaves used animals, plants and objects in Jamaica. The term – also rendered as Oba, Obia and Obi and its cognate Myal – probably derives from the Ibo-speaking peoples of the Bight of Biafra, dbia connoting an adept or master. To British observers the practice was a form of demonic magic. ‘Most people in the West Indies’, commented the Barbados soldier Thomas Walduck in one early report around 1710, ‘are given to the observation of dreams and omens, by their conversation wth the negros or the Indians, and some of the negros are a sort of magicians.’ While insisting that he personally was ‘very free from superstition’, he conceded he had ‘seen surprizing things done by them’. He could not help recording the story of one black man who appeared able to make birds disappear: ‘the master, mistress, and severall white people in the plantation would see them flye upon the tree, and then the negro would tell them if they could finde any of these foules … they have gott up into the tree severall at once, and could not.’ That ‘the negros here use naturall (or diabolical) magic no planter in Barbados doubts’, he reflected, ‘but how they doe it non of us knows.’ ‘That one negro can torment another is beyond doubt, by … unaccountable paines in different parts of their body, lameness, madness, loss of speech’ as well as the loss of the use of their limbs ‘without any pain’. Observers like Walduck tended to dismiss Obeah as mere trickery on the one hand while nevertheless granting the reality of its effects, suggesting how many whites placed their trust in black healers without ever understanding what they did.11

Those men and women who practised Obeah used plants in order to achieve hallucinogenic states of communion with ancestral spirits; to heal both whites and blacks; and to cast spells against and poison their enemies, from sadistic overseers to blacks who stole from each other’s provision grounds. Evidence collected in the late eighteenth century suggests the remarkable range of ingredients they incorporated. In 1789, the Jamaica Assembly’s London agent Stephen Fuller – who just happened to be Sloane’s step-grandson by marriage – enumerated for the House of Commons ‘the farrago of materials’, as he put it, which made up the contents of the obi or ‘fetish’ that Obeah men carried, often around their necks. These materials would be placed inside the hollow of a goat horn and included ‘blood, feathers, parrots beaks, dogs teeth, alligators teeth, broken bottles, grave dirt, rum, and eggshells’. The following decade, the Jamaica physician Benjamin Moseley wrote that the contents of the ‘obiah-bag’ carried by the fabled runaway slave Jack Mansong (known as Three-Fingered Jack) contained ashes, human and animal fat, a cat’s foot, a dry toad, a pig’s tail and ‘a slip of virginal parchment, of kid’s skin, with characters marked in blood’. Obeah turned abject substances, odd animal parts and the commonest objects into magical instruments that emboldened resistance to slavery. Tacky’s Rebellion, the largest slave uprising in the eighteenth-century British Caribbean, was led by Akan-speaking Coromantees in 1760 who were also practitioners of Obeah, leading the British authorities to ban its materials by law afterwards as a security measure.12

What did Sloane make of all this and what attention did he pay to the ways blacks engaged with the Jamaican environment? A number of English commentators at the time made tentative attempts at noting how blacks conceived of the operations of body and soul. In the 1680s, John Taylor claimed to have ‘discoursed with many old negroas, of witt and sence’ who told him that their ‘camaix (which signifies in their language shape and understanding) soon after death passeth into [their] own country, and ther lives for ever’. Writing to Sloane years later in 1717, Henry Barham described blacks’ use of a plant they called Attoo to plaster the bodies of the sick, as well as their interpretation of how it worked. They ground it into a paste to apply to the head and face and ‘sometimes their stomach if their heart is affected: for they attribute all inward ails or illness to the heart saying their heart is noe boon not knowing the situation of the stomach from that of the heart’. In the 1780s, Stephen Fuller would tell Parliament that Obeah men used ‘a narcotic potion, made with the juice of an herb (said to be the branched Calalue or species of Solannum) which occasions a trance or profound sleep of a certain duration’. He cited Sloane as a source.13

Sloane did collect species of Jamaican Solanum and, as we saw in the previous chapter, quizzed Africans repeatedly about medicinal plants. But, unlike some of his contemporaries, Sloane is strikingly quiet in the Natural History about practices such as Obeah, and makes only a few oblique references to black witchcraft. He was less curious about slaves’ knowledge than other travellers. A short, undated but singular entry in the catalogue of bird specimens he assembled typifies his dismissive attitude to black knowledge: ‘feathers made up to fright the slaves. Wald. Barb.’ The entry refers to some feathers sent by Captain Walduck in Barbados that were evidently part of the regalia of an Obeah man: the Jamaica planter historian Bryan Edwards later noted that one of the leaders of Tacky’s Rebellion, who had ‘administered the fetish’ to his associates, was ‘hung up with all his feathers and trumperies about him’ and publicly executed. Sloane’s catalogue entry thus turned the ‘frightening’ instruments of slave rebellion into a mere ornithological curiosity, jumbled among a list of hundreds of bird specimens. Sloane seems, moreover, to have been indifferent to the uses blacks made of the Jamaican plants he set about collecting. For example, the plant he described as Senae spuriae aut aspalatho affinis arbor siliqua foliis bifidis, flore pentapetalo vario (now known by the Linnaean name Bauhinia divaricata and popularly as the pom pom orchid tree) has been identified as one used hallucinogenically by slaves. If Sloane knew this, he did not say so in his writings. As we shall see, he composed lengthy descriptions of plants and their uses in his Natural History but for the most part did not include uses made by blacks. Part of the reason is surely that because African herbalism presented a formidable alternative to European medicine in the West Indies, Sloane had little motivation for crediting those black understandings of body and cosmology with which he was competing. Instead, he focused on turning Jamaican plants and animals into natural history specimens.fn1 It is to this process that we now turn.14

FROM PLANTATION TO HERBARIUM

Anyone who opens Sloane’s Natural History is struck by the quantity and detail of the hundreds of life-size engravings that burst from the pages of its two large folio volumes. Consider his engraving of cacao, the source of chocolate (here). Sloane intended such pictures not simply as supporting illustrations of the verbal descriptions of plants he composed but as carriers of essential scientific information about the anatomies of species which words alone could not arguably convey. These pictures constitute one of his greatest scientific achievements in providing a model of visual knowledge and by communicating the results of his Caribbean research to successive generations of botanists. Understanding how he made them requires exploring a chain of transatlantic processes: collecting, preserving, describing and drawing specimens in Jamaica, combined with subsequent research and additional illustration back in London. Executing these processes was a remarkable feat for the time. Turning specimens into anatomically precise pictures was arduous, especially in the Caribbean. ‘In that distant climate the heats and rains are excessive,’ Sloane admitted, ‘so that there are often hindrances upon those accounts.’ Jamaica’s uninhabited regions contained ‘several things very curious, but have no conveniencies for lodging men or horses, and are often full of serpents and other venomous creatures’ – not to mention fugitive slaves who stood ready to ambush their white enemies.15

Sloane’s plant collecting took advantage of environmental transplantations set in motion by others long before he ever stepped ashore in Jamaica. Cacao, for example, does not appear to have been native to the island but originated on the American mainland where the Maya and the Mexica (the pre-eminent people of the Aztec Empire in the Valley of Mexico) had consumed it for centuries. The Mexica served cacao, both hot and cold, mixed with various spices, maize and chili peppers, as a brew they knew as chocolatl – a Nahuatl word meaning bitter water. The Spanish discovered this drink in the sixteenth century, calling it chocolate, though Catholic observers baulked at its consumption in ritualistic indigenous ceremonies they identified with devil worship and, in line with Hippocratic assumptions about local climates moulding physical constitutions, feared that it would render them humorally degenerate and make their bodies more like those of Native Americans. Gradually, however, both Spanish-American Creoles and consumers on the Iberian Peninsula became avid chocolate drinkers, albeit in altered form, as they sweetened cacao with sugar. They brought the plant to Jamaica, establishing it as one of the island’s profitable early crops, harvested by slaves. Only ‘the most handy negroes’ were skilled enough to do this work, according to the French naturalist D. Quélus. They ‘go from tree to tree and from row to row, and with forked sticks or poles, cause the ripe nuts to fall down, taking great care not to touch those that are not so, as well as the blossoms’. When Sloane was in Jamaica, the cacao crop remained ravaged by a blight that had struck in the 1670s. Yet by this time various recipes for chocolate were already circulating in France, the Netherlands and England, giving rise to a flourishing culture of chocolate houses, the more socially exclusive counterparts of coffee houses. As a sign of his affiliation with this culture of luxury consumption, Sloane later acquired several gilt-rimmed earthenware chocolate cups bearing elaborate painted illustrations, apparently including one of Moses striking water from the rock (Plate 9).16

Sloane’s excursions from Spanish Town were also plant-hunting expeditions. Although he displayed little interest in what blacks thought about plants, he would have been well aware of how other naturalists used slaves to gather specimens for them. ‘Gathering and preserving … may be done by the hands of servants,’ advised John Woodward in his instructions for collectors, ‘and that too at their spare and leisure times: or in journies, in the plantations, in fishing, fowling, &c. without hindrance of any other business.’ After all, it could not be expected ‘that any one single person will have leisure to attend to so many things’. By the late seventeenth century, travellers increasingly employed slaves as collectors. Please ‘bestow on me 4 or 5 guinny negros’, the Virginia naturalist John Banister asked the Royal African Company. James Petiver, an apothecary based in Aldersgate, London, developed one of the largest natural history correspondences and became a close associate of Sloane’s after his return from Jamaica. Although he never credited their contributions in the lengthy specimen lists he published, Petiver systematized the use of slaves as collectors. By the 1690s, he directed correspondents to show slaves how to collect ‘shells with live snails inside’ and pin insects into pillboxes (or to the insides of hats), offering twelve pence per dozen plants and half a crown per dozen flies, beetles, grasshoppers or moths. ‘Procure correspondents for me wherever you come,’ he instructed the servant George Harris, who sailed on HMS Paramour with the astronomer Edmond Halley in 1698, ‘and take directions how to write them, and procure something from them [with whom] you stay, showing their slaves how to collect things by taking them along with you when you are abroad.’17

Sloane stated at its outset that the Natural History was based on local knowledge from ‘the inhabitants, either Europeans, Indians or Blacks’, but on only a few occasions did he credit slaves for accessing specimens he gathered. The company in which he rode up to St Ann’s, for example, included both knowledgeable planters and a ‘very good guide’, most likely an African (though possibly an Indian). Blacks, Sloane realized, knew the island better than anyone. Writing about the Palma spinosa minor (the prickly-pole), he noted that ‘negro’s travelling barefooted thro’ the woods, very carefully avoid places where these grow, because of the many prickles that fall from their stems and leaves’. His Radix fruticosa lutea or ‘chew sticks’ that were ‘us’d by the negroes for cleansing their teeth’, consisted of a root ‘taken up out of the woods of Jamaica by the blacks’. There was ‘no great difficulty in the curing or preserving of this fruit for use’, he wrote in the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions of the Jamaica pepper (which he expected to surpass ‘the East-India commodities of this kind’ in value) because ‘’tis for the most part done by the Negro’s; they climb the trees, and pull off the twigs with the unripe green fruit.’ Such acknowledgements were rare, but simply because Sloane said little about slaves’ work in finding plants does not mean that it was not substantial. As Petiver’s example shows, it was customary for naturalists not to credit their contributions, just as natural philosophers like Robert Boyle failed to acknowledge the laboratory technicians who carried out the experiments they then wrote up as their own. Notwithstanding this silence, there is little doubt that Sloane turned to slaves to aid his collecting since he regarded Jamaican blacks as a living link to Spanish and Taíno knowledge of the island’s species. He was well aware that the Jamaican environment had been reshaped over many years by botanical transplantation: the Spanish, he wrote, ‘had brought many fruit-trees from the main-continent, where they are masters’. And he believed that their knowledge had been passed on: ‘the skill of using’ Spanish crops ‘remain’d with the Blacks and the Indians’. So, while Sloane derided African healing, he ‘look’d into [it] as much as I could’ to try to know what they knew, not least ‘because of the great effects of the Jesuits Bark [Peruvian bark], found out by them’.18

Sloane therefore made sure to visit slaves’ provision grounds, their own ‘small plantations … wherein they took care to preserve and propagate such vegetables as grew in their own countries, to use them as they saw occasion’. He described several of their crops in the Natural History and collected specimens that remain immaculately preserved to this day in the Sloane Herbarium at London’s Natural History Museum. His herbarium volumes are astounding scientific pop-up books that contain dried fruits, leaves and stalks glued to the page as they were over 300 years ago, such as ‘the great bean’ (Phaseolus maximus perennis), which was ‘planted in most gardens, and provision plantations, where they last for many years’ (Plate 4). His sample of Milium indicum arundinaceo caulo granis flavescentibus is a striking specimen of Guinea corn ‘met with in some negro’s plantations’ (Plate 5). His okra probably came from provision grounds too; ‘Indians and Negroes commonly plant[ed] and use[d]’ the bell-peppers he collected as both medicine and food; and his Ceratoniae affinis siliquosa lauri folio singulari, ‘called Bichy by the Coromantin Negros’, was brought over on slave ships and used by blacks to treat stomach complaints. Rice was also ‘sowed by some of the negro’s in their gardens, and small plantations in Jamaica’. Whether Sloane seized the specimens he collected or exchanged for them is again unknown but he did talk to slaves about them. Writing about the so-called ‘hog doctor-tree’, he remarked that ‘a very understanding black assur’d me he saw a wounded hog go to this tree for relief.’19

Sloane naturally talked to many planters as well. He learned about how botanical transfers linked West Africa with the Caribbean. He noted how Bichy came to Jamaica as ‘a seed brought in a Guinea ship from that country’ and was ‘planted by Mr Gosse in Colonel Bourden’s plantation beyond Guanoboa’. Arachidna Indiae utriusque tetraphylla were nuts ‘brought from Guinea in the negroes ships, to feed the negroes withal in their voyage from Guinea to Jamaica’, which Sloane saw ‘planted, from Guinea seed, by Mr. Harrison, in his garden, in Liguanee’. And he observed that Scotch grass (later known as Guinea grass) came from ‘that part of Barbadoes called Scotland’, had been ‘brought hither, and is now all over the island in the moister land by rivers’ sides’, serving as feed for livestock. Comparison with other travellers again makes clear, however, the limits of Sloane’s curiosity about African knowledge. He described, for example, how vervain (verbena) was combined with onions in poultices for the treatment of dropsies; taken as a kind of hot tea; used in clysters (enemas) for belly ache; and drunk warm with lime root. He cited eminent European authorities’ accounts of it – the Spanish naturalist Nicolás Monardes and the Dutch physician Jacobus Bontius – and added, ‘it is very much in repute among the Indian and Negro doctors for the cure of most diseases.’ But there he stopped. Henry Barham, by contrast, went much further. In a manuscript natural history he later passed on to Sloane, Barham related how blacks used vervain to help those ‘bewitched with Oba [Obeah] which is a sort of Negro fascination or sorcery’ and relieve swellings, palpitations and fatal debility. Like Walduck, Barham thought Obeah was a trick of ‘faith’ and art of ‘persuasion’, though the effects of its poisons were undeniable and its antidotes, therefore, worth knowing about. Where plants like vervain provided Barham occasion to comment on black belief systems, Sloane limited his remarks to plants’ practical uses as he saw them.20

Such were Sloane’s observations from what he could see and learn through conversation. Once he had plants in hand, preserving them required enormous care. He did not record the exact techniques he employed, but contemporary accounts provide a good indication of how he probably proceeded. Herbaria were collections of dried plants that originated as objects of spiritual devotion but, after the work of Renaissance naturalists like Luca Ghini of Pisa, they evolved into botanical documentation centres replete with technical labels and notes. The practical demands were many. If the specimen was large, Woodward advised in his instructions the taking of ‘a fair sprig, about a foot in length, with the flower on’; for smaller ones like grasses and ferns, ‘take up the whole plant, root and all.’ Desiccation was of the essence: collectors should press plants between leaves of paper and hang them up to dry ‘in the air, at the top of some cabin, to keep them from rotting’. After thorough drying, they should then be placed between the leaves of a large book or quire of brown paper, spreading them smooth and even, before transferring them to more fresh pages ‘in some dry place, till they be sent over’ and flattened with a heavy weight. Costly supplies were called for which only wealthy patrons could afford. William Courten’s instructions to the Quaker James Reed, bound for the Caribbean in 1689, priced a single ream of paper at three shillings and sixpence. ‘I [have] gott severall plants not usuale,’ Thomas Grigg wrote to James Petiver in 1712 from Antigua, ‘but cannot save ym haveing no brown paper’ – itself a precious commodity imported from continental Europe. Sloane evidently faced no such difficulties and must have made few excursions without numerous quires to hand, likely carried by slaves.21

Labelling each specimen was crucial. The provenance of every sample should be noted on an accompanying sheet, urged Woodward, with the names ‘by which the country people call the plants … and the medicinal, or other uses, they make of them’. Ray provided a model of exactitude in provenance: in one memorable instance, he had described a plant in Cambridge as growing ‘on Jesus Colledge wall’. Sloane didn’t always measure up, however. ‘I found it in the woods,’ he later wrote of the Tilia forte arbor racemosa in the Natural History, ‘I cannot exactly tell where.’ ‘I found it in Jamaica’ was a phrase he reiterated several times, unable to summon further detail from either his notes or his memory. Slave plantations, however, provided trusty coordinates for mapping species in many instances. The fern Trichomanes foliolis longioribus eleganter grew ‘out of the fissures of the rocks, of each side on the Rio d’Oro, near Mr. Philpot’s plantation in Sixteen Mile Walk’; Hemiontidi affinis filix major thrived ‘on a woody shady hill, near the banks of the Rio Cobre, by the orange walk in the Crescent Plantation’; and the fern Filix ramosa maxima scandens flourished ‘in the woods on the roads between Guanaboa and Colonel Bourden’s plantation, on the side of Mount Diablo, and Archers Ridge’. Such observations underscore how important the assistance of Jamaica’s planters was in enabling Sloane to make collections and how his mapping of the island’s natural species relied on the artificial reference points supplied by plantations.22

Sloane’s main purpose in collecting plants was to publish pictures of them. Visualization, naturalists agreed, was essential to producing better scientific knowledge. In his Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language (1668), John Wilkins had argued that language itself should be reformed to possess an immediacy akin to that of pictures. Obfuscating words were the problem, he held, and pictures the solution: language should be more like a picture. Increasingly, those few naturalists with sufficient wealth turned to the production of engravings using finely wrought copper plates to print multiple copies of drawings, a technique that succeeded the cruder woodcuts of the sixteenth century. There was, however, no self-evident form of ‘accurate’ scientific representation: as methods of visualization continued to evolve, naturalists did not reach consensus about how best to picture nature. After the 1730s, Linnaean botany would usher in a tendency among illustrators to draw pictures that gathered together anatomical characteristics from several different samples of the same plant to create idealized composite images of a given species, believing these to be truer to their essential forms than any individual specimen could ever be. But Sloane was guided by his Baconianism, which prescribed the gathering of strictly factual particulars in all their unsystematic and unidealized individual variety as the greatest guide to what existed in nature. He also placed his trust in Ray, adopting as his own his friend’s method of classification by scrutinizing all of a plant’s characters rather than focusing on one single feature. These commitments led Sloane to produce large and detailed pictures of individual specimens.23

Sloane’s handling of cacao provides a vivid example of how he turned specific plants into pictures of scientific species. The cacao specimen he collected in Jamaica is stuck on to the fifty-ninth page of the fifth volume of his Jamaica herbarium (pp 104–5). The browned leaves of the cacao tree are pressed on to the right-hand side of the page, where they have been glued (and subsequently taped) in place, with only incidental damage and decay over three centuries. Glued above the leaves are several of cacao’s tiny flowers, also brown with age, while below a cacao nut has been stuck to the page with fragments from the bark of the pod that contained it. In Jamaica, Sloane would have placed freshly acquired specimens into loose quires of paper, dried and repacked them in the manner described by Woodward, before putting them (long afterwards) into the bound folio volumes of his herbarium once back in London, where his herbarium was ‘pasted and sticht’ together by several assistants, possibly including Henry Hunt, who worked at the Royal Society assisting Robert Hooke with his experiments, drawing and printing, and curating its Repository. Once the plant was in place, Sloane wrote up a label and pasted it at the foot of the page to identify each sample, whose names he derived wherever possible from previous descriptions in Ray’s Historia plantarum, which he used as a guide to known species.24

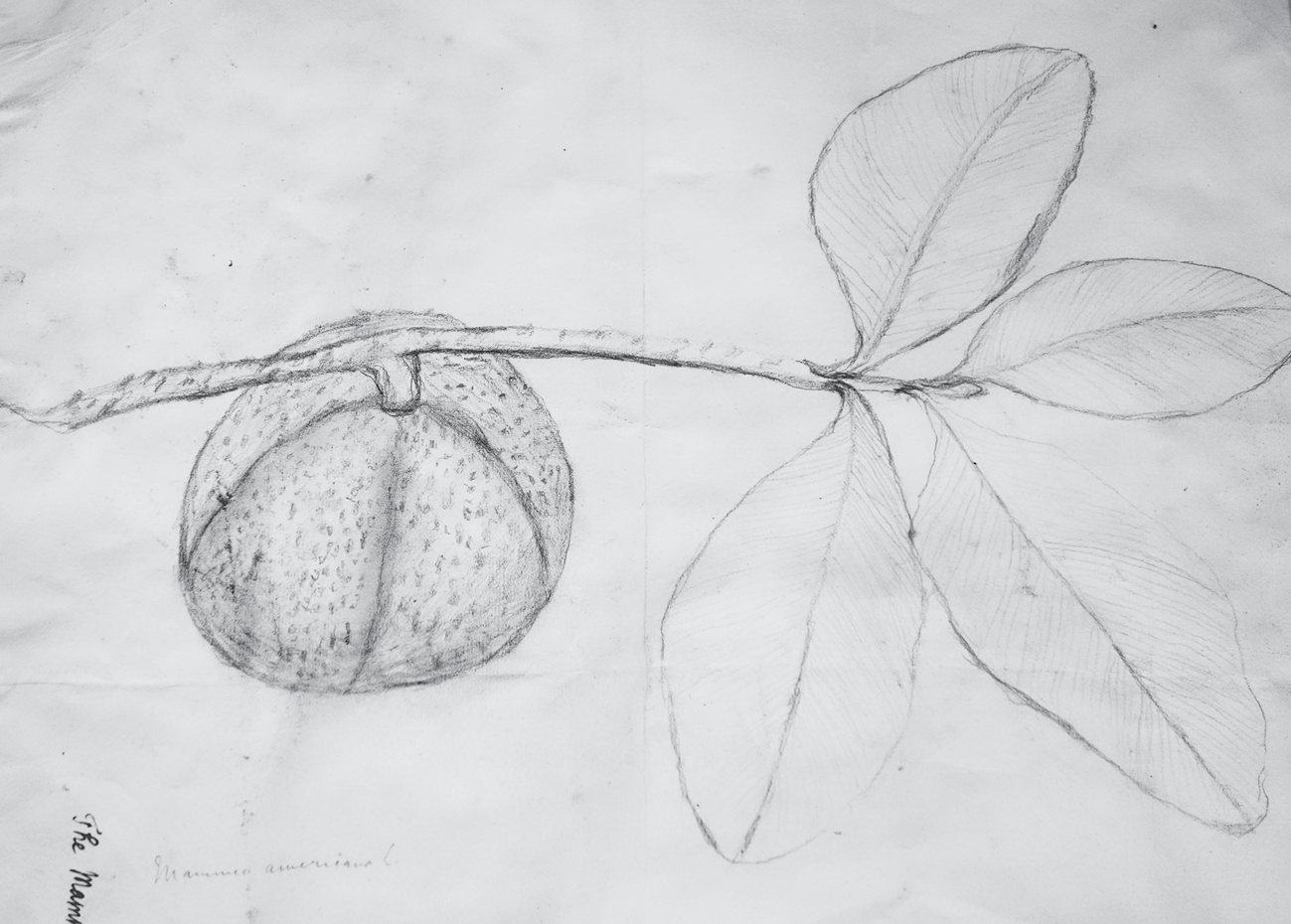

But Sloane brought more than just specimens back from the Caribbean. Pasted opposite his cacao sample is a page of paper that came from Jamaica and which bears the image of a living cacao plant with its weighty nut-filled pods (‘a stalk or branch of cacao wt ye fruit’, as Sloane labelled it). The picture was not, however, drawn by Sloane. Most naturalists were not accomplished in artistic technique, since they aspired to be recognized as gentleman authors and men of letters, while draughtsmanship was typically regarded as a form of lower-class artisanal dexterity. This picture of a live cacao plant was in fact drawn by one of Sloane’s companions on the journey to and from St Ann’s: a minister named Garrett Moore, who was ‘one of the best designers I could meet with there’, Sloane wrote, and so ‘[I] carried him with me into several places of the country.’ Drawing plants in situ was another means of collecting them when one ‘met with fruits that could not be dried or kept’, such as the pineapple, which Moore sketched for Sloane (Plate 6). Moore executed a number of drawings in both terracotta crayon and pencil, including many trees done ‘from the life [and] in their natural bigness’. Sloane undoubtedly paid Moore well for his labours, but he had other promises at his disposal as well. ‘You were pleased when heare to promis to speake to my Lord Bishope of London,’ Moore later reminded him, intimating a pledge on Sloane’s part to improve his standing within the church. Moore also requested cloth, oil and pencils ‘to draw what peeces you will have done’, which Sloane undoubtedly supplied.25

Moore’s sketches were only the beginning of the visualization process: they provided the basis for a second round of illustrations completed years later, a full decade after Sloane returned to London. After Jamaica, Sloane became so busy with his medical practice, his work at the Royal Society and his collections that it was only during 1699–1701 that he commissioned Everhardus Kickius, one of many Dutch artists working in England at the time, to complete his visual catalogue for the Natural History. Kickius’ task was two-fold: to draw those dried specimens from Jamaica that Moore had not sketched in situ (and objects like Sloane’s strum strums); and to use Moore’s original sketches of living plants and combine them with details from dried ones to produce composite pictures that captured all of a flowering plant’s different parts. The drawing of the live cacao plant in Sloane’s herbarium is thus signed ‘E. K.’ for Everhardus Kickius – but in reality it is a sketch done by Moore in Jamaica which Kickius inked over later in London, either to correct certain details according to Sloane’s instructions or simply to preserve the pencil sketch from fading. To this he then added sketches of the dried cacao flowers, nut and pod bark done from Sloane’s specimens. This composite picture of cacao, including both live and preserved elements, then formed the basis for one of the engravings in Sloane’s second Jamaica volume (opposite), which were executed for him by another Dutchman, Michael van der Gucht, and by an English engraver, John Savage, who also made pictures for the Philosophical Transactions. At one point in the herbarium, Moore and Kickius seem to meet where both of their names appear next to a picture of a Jamaican jasmine tree. But this meeting is an illusion – one produced by Sloane’s ability to collate the work of different artists separated both by an ocean and by a decade in time.26

There was, therefore, a distinct art to the naturalism of Sloane’s pictures: he artificially combined the elements of both living and dried specimens in unified views to depict all of a plant’s features. There are numerous examples of such artifice in his Natural History. His engraving of the mammee tree was a composite based on a drawing by Kickius that again combined elements from Sloane’s dried specimen with a live picture Moore had drawn in Jamaica (here). Yet Sloane evidently wished his readers to believe they were seeing an individual specimen exactly as it was, so the line of shadow across the mammee fruit Moore and then Kickius drew, cast by an overhanging stalk, was retained in the final engraving, conveying the illusion of a specific plant drawn at a given moment in time. Sloane’s engraving of the clammy cherry tree likewise combined fruits and leaves drawn in crayon by Moore (on a piece of paper Sloane brought back from Jamaica and had pasted into his herbarium) with anatomical details Kickius later supplied from Sloane’s dried specimen of the same species (Plate 7). ‘I saw it in Jamaica,’ Sloane routinely remarked of the species he had illustrated. The seemingly self-evident act of seeing plants in the pages of his Natural History is, however, to behold a subtle work of colonial scientific art. These were pictures made neither in Jamaica nor in London, strictly speaking, but by movement and coordination between England and the West Indies.27

Like numerous gentleman naturalists who depended on others to make pictures for them, Sloane sought to exercise close scrutiny over his draughtsmen. Although their skills were fundamental to his science, the difference in status between learned authors and visual ‘workmen’ (as Sloane referred to them) was significant. Engravers signed their pictures in published books, but apart from a brief acknowledgement in Sloane’s introduction, the names of Moore and Kickius were absent from the Natural History (other assistants like Henry Hunt, who may have assembled Sloane’s Jamaica herbarium, left no named trace behind them at all). Such collaborations were subject to disagreement, as authors tried to ensure that their artists gave them exactly the kinds of pictures they were paying for. Some of Sloane’s corrections of Kickius’ drafts can be found in the herbarium. ‘Leaves sett too thick’, he wrote on a piece of paper with an ink sketch of a convolvulus stalk; ‘disjoine the leaf and flour at ye stalk which should be left out,’ he indicated elsewhere. The detail both Moore and Kickius rendered is extraordinary, as shown by countless examples like Kickius’ painstaking work on specimens of Lonchitis altissima (Plate 8), which lies folded several times over in the herbarium, and his striking Viscum cariophylloides maximum. Much of the scientific value of Sloane’s Caribbean travels lay in this artistic command. ‘I am sensible that the charge of figures may deter you,’ the penny-pinched Ray had earlier counselled him, so ‘draw them in piccolo, using a small scale, and thrust many species into a plate.’ But this was precisely what Sloane did not do, ultimately spending a remarkable £500 on a total of 274 engravings. Where specimens were invariably subject to damage and decay, publishing detailed engravings would allow Sloane to circulate his stunning collections as ageless pictures, allowing readers, wherever they might be, to examine them as if they too had made the voyage to Jamaica.28

When the Swedish naturalist Carolus Linnaeus reorganized plant classification according to sexual characteristics and through the use of binomial nomenclature, beginning in the 1730s, his achievement consisted in doing away with the cumbersome polynomials over which Sloane spilled so much ink. Although Sloane went on to become a standard reference point in natural histories of the West Indies, some Linnaean naturalists like the Irish physician Patrick Browne (the author of a work on Jamaica published in 1756) criticized his labours as inaccurate and outmoded. Linnaeus himself, however, worked from a copy of Sloane’s Natural History as he composed his 1753 Species plantarum – still the standard departure point for plant taxonomy – citing its engravings as authoritative illustrations of the species he classified. Many of Sloane’s fellow botanists around Europe (Linnaeus included) were in all likelihood unable to read his plant descriptions, since these were written in English for the benefit of his fellow countrymen, rather than in Latin, the lingua franca of natural history. And it was for this reason that the botanist Antoine de Jussieu asked Sloane in 1714 if ‘a sample of figures could be detached from the body of the work’ and sent to Paris, regretting that his ‘ignorance of the English language deprives me of the benefit I might derive from reading your history’. Sloane doubtless obliged. At least one London bookseller, Thomas Osborne of Gray’s Inn, sold ‘cuts’ of Sloane’s pictures without the Natural History’s text – such was their value as stand-alone scientific sources. For many of Sloane’s readers, the greatest scientific value of his Natural History lay in its artistic ability to show them what grew in Jamaica without their ever leaving Europe.29

But pictures could never completely do away with words. Sloane collated his images with vast amounts of text to produce a work that combined extraordinary visual detail with encyclopaedic botanical description. Indeed, verbal description remained important in late seventeenth-century botany as an authoritative (and inexpensive) means of assembling information about species, as exemplified by works like Ray’s densely textual Historia plantarum. In addition to producing a wealth of pictures, therefore, Sloane made thorough verbal accounts of species to record information not easily captured in visual terms such as colour (though he admitted colour was ‘very hard to describe’) and to preserve information that might be lost if his specimens got damaged in transit. Like picturing, verbal description entailed an extended transatlantic process. Sloane ‘immediately described [plants] in a journal’ as he collected them and kept both notes and specimens together. Page 68 of volume three of the Sloane Herbarium, for example, contains a specimen with a sheet of paper pasted opposite with notes in Sloane’s hand. These appear to be notes made in Jamaica that label the sample Filia forte foliis subrotundis mali colonea and record its anatomy: it ‘had a gray smooth bark wt a white wood under it’ and had ‘on its branches & twiggs many leaves wch grew out alternatively’. Sloane also noted measurements of the plant’s parts and the ‘yellowish green colour’ of its leaves. He fell back on the authority of his own senses, expecting that readers would trust his word as a gentleman as he explained that he measured plants’ ‘several parts by my thumb, which, with a little allowance, I reckoned an inch’, although he conceded that measures taken in this ‘gross manner’ sometimes proved unsatisfactory and that ‘more nice measuring’ would have been preferable. Many species had parts ‘so extraordinary small as not to be easily visible’, he granted, ‘and perhaps others have perfect flowers, which escap’d my observation.’30

Emulating Ray once more, Sloane chose to exclude folkloric and philological information about species and concentrate on their physical characteristics, distancing himself from the methods of famed Renaissance naturalists like Konrad Gessner and what Ray called ‘human learning’. ‘We have wholly omitted’, Ray had declared in his Ornithology (1678), ‘hieroglyphics, emblems, morals, fables, presages or aught else appertaining to divinity, ethics, grammar, or any sort of human learning; and present … only what properly relates to natural history.’ Sloane thus focused on providing detailed anatomical descriptions. The cacao tree he observed was 15 feet tall, he wrote, ‘with a grey and almost smooth bark, and a trunk as thick as ones thigh’. Its flowers had only half-inch stalks and were ‘made up of 5 capsular leaves, 5 crooked petals, several stamina, and a stylus, of a very pale purple colour’. Its fruit was ‘7 inches long and two and a half broad in the middle where broadest, of a yellowish green colour, hard and pointed’ and, when ripe, ‘as big as one’s fist’. It was ‘a deep purple colour’ and its shell ‘about half a crown’s thickness’. It contained many kernels ‘of an oval shape’, each covered by a mucous membrane and each as large as a pistachio nut. The nuts inside the pods were ‘made up of several parts like an ox’s kidney’ and the pulp inside the pods – which Sloane tasted – was ‘oyly and bitterish to the taste’.31

In his analysis of the development of early modern natural history, Michel Foucault argued that the seventeenth century witnessed a decisive shift from depicting species as magical Renaissance emblems, oozing with symbolic meaning, to naturalistic anatomical diagrams that stripped them down to their corporeal essence, exemplified by the dominance of Linnaean plant illustration in the Enlightenment. Sloane shunned anthropomorphism and folklore, yet anatomical description constituted only a small fraction of his account of cacao, as he compiled a series of notes about the culinary, medicinal and commercial aspects of plants, which he later combined in London with information excerpted from books in the library he began building up. This utilitarian encyclopaedism followed the example set by previous travel writers. A century earlier, the Spanish naturalist Francisco Hernández had taken extensive notes on the medicinal properties of a drink known as cacahoaquáhuitl (a version of chocolate) based on interviews with the indigenous inhabitants of Mexico City, where he spent several years during 1570–77. These notes were published in his posthumous Rerum medicarum Novae Hispaniae thesaurus (1651), and Sloane subsequently acquired a number of Hernández’s Latin manuscripts, from which he would translate a total of forty-eight extracts for his own Natural History. Combining botanical, medicinal and commercial intelligence about species was common in natural history. Sloane’s contemporary Thomas Trapham had advocated the use of chocolate as a health food since at least 1670 and Sloane followed suit. ‘Chocolate is here us’d by all people, at all times,’ he observed, noting how cacao trees had to be shaded from the sun and their nuts thoroughly dried for torrefaction, although it was precisely their ‘oiliness’ that made chocolate so nourishing, especially when mixed with eggs. ‘The common usage of drinking it came from the Spaniards,’ he acknowledged, earlier recipes including spices such as Indian pepper, and he raided the accounts of Spanish rivals to cite well-known sources such as the Jesuit José de Acosta as well as Hernández. English recipes for chocolate, however, were different: ‘ours here is plain, without spice,’ and Sloane later collected recipes for making chocolate ‘the Spanish way’ and ‘the English way’ – with eggs and milk, respectively. Chocolate ‘colour[ed] the excrements of those feeding on it … a dirty colour’, he found, and was ‘nauseous, and hard of digestion’, which made him ‘unwilling to allow weak stomachs the use of it’, even though infants drank it in Jamaica ‘as commonly as in England they feed on milk’. If taken warm, however, it proved especially beneficial. So Sloane experimented by sweetening medicines with chocolate. The stuff could stop bloody fluxes (dysentery), he believed, provide essential nourishment and even promote ‘venery’. It was also highly lucrative. When English merchants sold slaves as contraband to neighbouring Spanish colonies, they often got large quantities of cacao in return, which they then sold back in England at a hefty mark-up of 55 per cent.32

Sloane also remained fascinated by the striking cultural functions attached to specific plants. Cacao, he noted, was particularly curious because it was used as a form of money in several Native American societies and he spent considerable time scouring other books to find evidence to this effect. He cited sixteenth-century Spanish sources like Peter Martyr and Hernández, who had concocted a romantic contrast between Europeans’ corruption by gold with Native American virtue as embodied by their use of cacao nuts as money. In addition to raiding the natural histories of England’s imperial rivals, Sloane quoted English sources, too, such as the traveller John Chilton, who described how the natives of Nova Hispania ‘pay the king their tribute in cacao, giving him four hundred carga’s, and every carga is twenty four thousand almonds’, as well as the pirate William Dampier, who circumnavigated the globe in the 1690s and who likewise observed that cacao grew ‘in the Bay of Campeche, where the nuts pass for money’. In the end, despite his commitment to the sober anatomical depiction of species through both word and image, Sloane actually spent more time in his Natural History describing chocolate’s function as currency than on its medicinal properties or even commercial value. Unlike Martyr and Hernández, he did not comment on the meaning of such intriguing usages, however, preferring to curate the pages of his book like a cabinet of curiosities – leaving it to readers to form their own judgements about what they found there.33

Thus it was that Sloane assembled with enormous pains, and over many years, the vast botanical catalogue that constituted the centrepiece of the Natural History. While in Jamaica, he collected plants, took notes on them and had them drawn from the life as he travelled between plantations, preserving his specimens, notes and pictures as he went. Back in London, he had his specimens transferred to a bound herbarium, had more drawings made and conducted further research. His drawings formed the basis for his numerous ‘large copper-plates as big as the life’, as advertised on his title page, inviting readers to examine his specimens as though looking at the real things, spread over double pages in an unstitched folio edition designed to be opened out, complete with wide margins for making annotations. At the same time, Sloane compiled an encyclopaedic work of reference that showcased his learning by combining anatomical description with medicinal, commercial and ethnographic information. The result was a work that invited readers to move back and forth between image and text and study them together. Joining fieldwork with research back in London, Sloane’s natural history was at once emphatically visual and deeply learned, intended for both Caribbean colonists and European naturalists, and one of the age’s most spectacular works of colonial science.34

FLESHY BODIES ARE CERTAINLY PRESERVED

Plantations transformed Caribbean landscapes in obvious ways but also in ways Sloane and his contemporaries little suspected, with creatures sometimes barely visible playing dramatic roles. Sloane’s Jamaican medical career owed a great deal to the buzzing of the mosquito, for instance, and the environmental factors that allowed it to reproduce in great numbers. The Taíno had regularly burnt woods as part of their pastoral culture, so their extinction led to a temporary reforestation of the island before the clearances the English made to establish plantations and harvest timber. This deforestation, however, produced unintended effects. Sloane remarked in passing on the ‘troublesome’ buzzing of mosquitoes, observed that whites used gauze nets to keep them at bay and noted that Africans and Indians set smoky ‘fires near the places where they and their children sleep … both for their healths sake, and to keep themselves from gnats, mosquitos or flies’. But he did not dwell on the matter. He did not realize that these creatures carried diseases that would later be identified as yellow fever, brought over from West Africa on slave ships, and malaria. Nor did he understand that the accumulation of stagnant rainwater in cisterns and clay pots allowed mosquitoes to hatch eggs on a far greater scale than before, exacerbated by the clearing of Jamaica’s woodland (which reduced the island’s insectivorous bird population) and the fencing in of savannahs to create livestock pens (which expanded the numbers of cattle and pigs on whose blood mosquitoes gorged). Sloane’s livelihood was thus gifted to him in part by the unanticipated environmental consequences of colonization and the mosquito’s meddlesome buzz.35

Collecting animals formed an integral part of natural history, and one that inevitably presented greater practical challenges than the collection of plants. Sloane hoped to contribute specimens for the compiling of new species catalogues by colleagues like Ray, who were busily engaged in assembling comprehensive classifications of fish, insects and other creatures based on what travellers could find. They often focused on animals they believed would be relatively straightforward to accumulate in great numbers, allowing them to constitute entire series as God had created them, such as insects, their physical fragility notwithstanding. Typically, the questions European naturalists asked about animals pertained to commercial exploitation as much as taxonomy. Could horses, cats and cows survive on the island while drinking virtually no water? Did fireflies stay bright after they died? Could hogs tolerate brackish water even though men could not? And was there really a ‘magotti savanna’ where maggots bred spontaneously in the rain? Such questions, posed by the questionnaire Governor Thomas Lynch took with him to Jamaica in 1670–71, show the range of concerns animating animal study at the time. They reveal how ignorant English naturalists remained concerning the basic behaviours of many different creatures. Most interestingly, the query about spontaneous generation shows that while naturalists may have dreamed of assembling providential catalogues that brought their taxonomies to a state of rational perfection, they still wondered whether monstrous forms of life awaited them in the degenerate landscapes of the torrid zone.36

Sloane’s ability to acquire Jamaican animals depended on local assistants, including African and Indian hunters, fishermen and divers. For example, Sloane had many birds and fish sketched by Garrett Moore, whose drawings formed the basis for a large number of engravings. These were almost certainly done from creatures obtained by local hunters. Although Sloane did not acknowledge this, he tellingly remarked several times on hunters’ prowess. He noted how blacks and Indians used ‘gangs of dogs’ to catch wild hogs, for example, which they ‘fill’d with salt and expos’d to the sun, which is call’d jirking’ and ‘brought [them] home to their masters’. Indians in particular made ‘very good hunters, fishers, or fowlers’ and were ‘very exquisite at this game’, while Africans cleverly caught fish ‘by intoxicating them with dogwood-bark’. Sloane conversed with African hunters: ‘a negro hunter told me the berries [of the currans tree] were not eatable but poysonous,’ he noted, while another told him of saving a companion from a snake who had twisted itself around his body until ‘he could not speak’. Sloane bought animals at market. Iguanas, which he collected and had figured, made ‘very fat and good meat’; he was assured they had been ‘commonly sold for half a crown a piece in the publick markets’ when the English first arrived. He saw pampuses, garfish, gurnets, pilot fish and barracudas for sale; the geroom, he noted, was ‘taken at Old Harbour, and brought to market, where I had it’. He likely bought his corals and sea urchins from Indian and African divers, who harvested the nearby pearl fishery off Santa Margarita Island for the Spanish, and whom the English employed on salvage dives and to conduct hull maintenance on ships at Port Royal.37

Sloane inventoried the island’s beasts of burden and its livestock. Under the heading equus, for instance, he related that Jamaica’s horses had first been introduced by the Spanish, were ‘small, swift, and well turn’d’ and were often taken wild; he added that he had ‘several stones taken out of dead horses bodies in Jamaica, which are very ponderous and of different shapes’; and he referred his readers to previous accounts in works on quadrupeds by Ray and the German naturalist Elias Brackenhoffer. But that was it – no anatomical descriptions and no pictures. His accounts of oxen, deer, hogs and chickens also lacked detail. Sloane dutifully catalogued these commodities but they held little interest for him: they were simply too common. They weren’t curious. The Ovis africana (Guinea sheep) interested him because of its African provenance but little more. Asinus, the ass, merited but one sentence: ‘they are in Jamaica.’ Cattle were redeemed only by the hairballs that ‘the peristaltick motion of the paunch’ threw up as ‘a fine and comely ball of the bigness almost of ones fist’. Sloane acquired several samples. Here at last was something curious with hidden utility. These oddly attractive clumps of matter harboured little-known medicinal properties: ‘some of this powder’d and given half a drahm is said to be a powerful astringent.’38

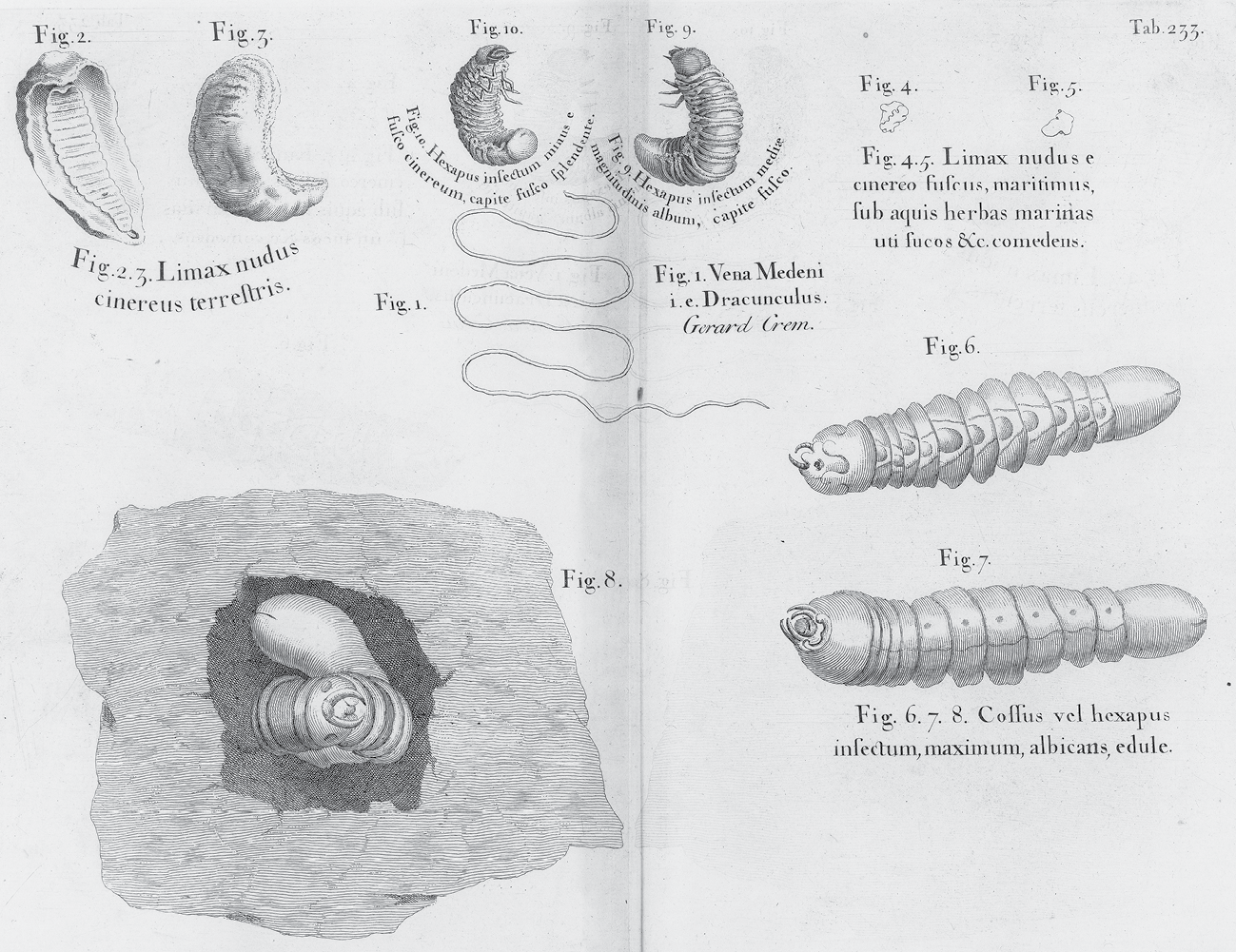

Sloane lavished attention instead on rare species about which Europeans were ignorant. His exacting curiosity about the skink, or galliwasp as it was called in Jamaica, makes a vivid case in point (here). Sloane dissected and examined skinks, meticulously describing their anatomy. Scincus maximus fuscus was 11 inches from head to tail and 6 around the middle; its ‘back was hard, and a little compress’d, and so was the belly’; it had two ‘round spiracula or nostrils in the two corners of the snout’; and its feet resembled those of a lizard, with two joints and five toes. Its anus was covered ‘with a transverse flap’ and its back was covered with ‘rhomboidall small rowes of scales of a brown colour, with spots of orange’. It had a ‘short larinx’ and ‘lungs not altogether membranaceous, the heart as of other animals, the stomach not all muscular, but made not sack fashion, but of several wide circumvolutions, with cells like those of the colon in other animals, and with all very thin and wide’. It lived on marshy ground, fed on crabs and was ‘reckoned very poisonous in the bite’: Sloane was ‘told one [person] had his thigh bit by this creature and dy’d the next day’. In reality, it was incurably shy but even though ‘it flyes from a man,’ it ‘loves to feed on the remainder of his victuals’. Sloane acquired several samples, listing ‘skinks of severall colours’ in his Quadrupeds Catalogue; had pictures of them drawn and included in the Natural History; and stored specimens for medicinal use in his pharmacopeia drawers. Both timid and dangerous, skinks were the kind of prey which only skilled hunters could take and which Sloane likely bought, therefore, at African markets.39

As with his plants, Sloane did not detail his methods of preservation, but a printed sheet of ‘Brief and Easie Directions’ circulated by James Petiver to his correspondents describes key period techniques. All ‘beasts, birds, fishes, serpents, lizards, and other fleshy bodies capable of corruption, are certainly preserved’, Petiver directed, by immersing them in ‘rack, rum, brandy or other spirits’ or brine, together with three or four handfuls of salt added to each gallon of fluid and a spoon or two of powdered alum. Any simple pot, bottle or jar would do, with a corked or resined top. For large fowl, the head, legs or wings were welcome; smaller birds and insects should be sent entire ‘drowned’ in spirits. If dried, the entrails should be removed first by cutting under the wing, stuffing with ockham or tow mixed with pitch and tar, and drying in the sun. Desiccation was again vital to ‘kill the vermin which often breed in’ specimens. Woodward’s instructions suggested the considerable dexterity required to secure delicate specimens in boxes padded with chaff or cotton. Shells, minerals and corals ‘ought to be put up carefully in a piece of paper … by it self, to prevent rubbing, fretting, or breaking in carriage: and then all put together into some box, trunk, or old barrel, placing the heaviest and hardest at the bottom’. Woodward insisted that ‘great caution ought to be used that the boxes wherein they are, be not turned topsy-turvy, or much tumbled and shaken in carrying to and from the ship’. Courten’s collector James Reed carried a dozen pairs of scissors that cost a shilling and sixpence; two dozen knives at four pence; fish-hooks at two shillings and sixpence; one hundred needles for a shilling; a gallon of spirit of wine for sixpence; several boxes, also for sixpence; and two glass bottles for three pence. Sloane doubtless carried a large number of such supplies.40

Insects commanded special attention. Because they were especially challenging to collect and preserve, they had become a darling fetish of the naturalist in a spectacular reversal of cultural fortune. Christians believed that insects had been absent from the Garden of Eden and had only emerged as a consequence of original sin. So, in addition to scathing vernacular about ‘dunghills’ and ‘pisspots’, Caribbean travellers’ invocation of insects to paint Jamaica as physically degenerate (hence the ‘magotti savanna’) smacked of ungodliness as well. However, since the sixteenth century, insects had risen to divine heights in human estimation. Through its microscopic engravings of fleas and flies, Robert Hooke’s Micrographia (1665) astounded readers with glimpses of undreamed-of worlds. Sloane, in common with many contemporaries, emphasized the value of insect study in revealing the microstructures of the creation. ‘The power, wisdom and providence of God Almighty, the creator and preserver of all things,’ he declared, ‘appear no where more than in the smallest animals, called insects’, which, despite their ‘little bodies and many enemies … live, thrive, and propagate their kind, so that since we have an exact history of them, none seem to be lost.’ This was the dream of total knowledge in Christian natural history: the universe had not changed since the creation so naturalists could aspire to assemble complete catalogues of natural kinds.41

Obtaining insects in Jamaica served this aim of universal cataloguing. Some Sloane evidently caught himself, perhaps even in his own house in Spanish Town, such as the great house spider that was ‘very common in all houses, running about even on their cielings’. Slaves probably contributed a number of specimens. Petiver directed his correspondents to pay slaves to collect and went into great detail regarding insects in particular. ‘Hire a negro or any labouring man’, he told one supplier, ‘to goe up into ye island or ye woods and highest mountains.’ He worked out a pay scale of ‘halfe a crown a dozen for every different fly, beetle, grasshopper, moth &c’. Like Petiver, Sloane did not record which species he got from slaves, but he did provenance such specimens like his plants, observing for example that he had found the ‘naked white’ snail Limax nudus ‘in the woods near Captain Drax’s plantation in the north side of the island by the old town of Sevilla’. Other samples came to him as gifts. After leaving Jamaica, he received a parcel of cotton-tree worms (the Cossus, that delicacy savoured by both African slaves and ancient Romans) from the wife of a planter named John Leming, ‘according to promise … together with the wood wherein they were’. The brown and white spider called Araneus niger minor, he noted, was ‘brought to me from Jamaica by Mr. Barham’.42

Mrs Leming’s worms fascinated Sloane for what they did as much as for what they were. He listed several of them in his Insects Catalogue as well as ‘a piece of sallow wood wherein was lodged a cossus’. Sloane dissected a number of these creatures, describing the water and fat that issued from their bodies as he worked and the ‘black, hard, hairy sharp claws, with which it … corroded rotten wood’. Insects like the cochineal beetle, used to make a lucrative red dye, could make imperial fortunes: Sloane reported with furtive excitement that a few bags of them had been brought to the island by privateers and had ‘taken life and crept about’. But worms like the Cossus could devour imperial fortunes just as fast. Sloane’s collection of worm-eaten keels testified to this menace: in one instance, he shelled out one pound and six shillings to procure a single exemplary ‘timberworm which eats ships in West Indies’. He commissioned engravings for his Natural History that deviated from the customary specimen views of most naturalists – decontextualizing the specimen by abstracting it on to a white background – by illustrating such worms boring through wood, for example the Scolopendra maxima maritima, which burrowed through the oak and cedar hulls of English ships, notwithstanding their coats of allegedly impervious resin (opposite). The wood of the juniper tree could, it was said, withstand such ‘all-devouring’ vermin, but Sloane for one doubted it very much, having ‘seen keels of ships of this wood eaten thro’ and thro’’.43

Sloane’s entomology was thus embedded in British maritime and imperial economic interests, which worms also threatened by invading the bodies of slaves. ‘Worms of all sorts are very common amongst all kinds of people here,’ Sloane observed, ‘especially the blacks and ordinary servants.’ They caused fevers, convulsions and stomach pains, rendering slaves unfit for work. The long worm lodged ‘amongst the muscular flesh under the skin, in several parts of the bodies of negroes and others coming from Guinea’. Gold Coast natives suffered more than Angolans or Gambians. Sloane examined at least one slave who had a worm ‘in his thigh, [whence] half an inch of the end of was hanging out, which was flat and blackish’. He ‘was told that the only remedy for this distemper was to draw it out by degrees every day some upon a round piece of wood, as a piece of tape or ribbond’ and was ‘assured that if any part of this worm, which is tender and very long, and requires great care in the management of it, should chance to break within the skin, that there follows an incurable ulcer’. Black children often got worms from sucking raw sugar cane, vomiting them up in ‘divers shapes and magnitudes’, prompting Sloane to try a range of purgatives as well as bleeding, but often without success as the worms ate ‘through the[ir] guts’. His interventions were once more an attempt to use his medical expertise in defence of slavery. In his Insects Catalogue, he described a ‘long worm drawn by piece meal from the Guinea negros leggs and other muscular parts’ sent to him years later by John Burnet, a South Sea Company surgeon tasked with inspecting cargoes of slaves shipped to Cartagena in South America for sale to the Spanish colonies.44

While dismissive of African healers, like many whites in the Caribbean Sloane took advantage of blacks’ manual dexterity to rid his own body of a parasite. ‘I found an uneasiness, soreness, or pain in one of my toes,’ he recounted of one occasion, so he sought help from a slave woman. ‘I had a negro, famous for her ability in such cases, who told me it was a chego.’ The woman in question, who he said ‘had been a queen in her own country’, opened Sloane’s skin with a pin above the swelling, pulled out the ‘tumour’ and filled the wound with tobacco ashes from a pipe she had been smoking. The swelling had resulted from eggs laid by female fleas and ‘after a very small smarting it was cured.’ Sloane recorded another case that showed how delicate such operations were, where ‘a very neat lady had one of these bags bred in one of her toes’ and ‘part of it was by a black taken out with a pin,’ though ‘not the whole bag’. As the swelling ulcerated, Sloane declined to intervene, protesting that as a physician this was not his ‘proper business’, referring the woman instead to a surgeon, ‘who applying poultesses, &c. to it, it broke and kept running for a long time, after which it cicatriz’d not without great trouble’. A later report by Henry Barham calls forth an interesting question about which blacks were most adept at such operations. Writing to Sloane in 1718, Barham described the ‘trumpery’ of ‘oba or doctor negroes’, some of whom ‘whissels at the time they draw [the worm] out pretending they got it out by that’, rather than attributing their success to the quill they used to perform the extraction. This raises the intriguing possibility that Sloane may have had his swelling healed by one of the Obeah women whose beliefs he so scorned.45

Once secured, insects again confronted Sloane with the question of how to have them drawn. In the late seventeenth century, consensus was elusive on whether insects should be classified according to their modes of generation or their anatomical variation, so naturalists differed over whether artists should draw them to capture their development over time or to render their bodies as they appeared at a specific instant. Because he was collecting and preserving dead specimens, rather than keeping live insects over an extended period, Sloane had Garrett Moore draw specimen views that brought out static yet clear anatomical details. Table 237 in volume two of the Natural History presents a host of insects in this way, including beetles, cockroaches and bedbugs. Sloane supplied full Latin polynomial labels and, as with his plants, referred readers back to descriptions by previous naturalists including Ray, gave insects’ English names and provided brief descriptions. He also had these specimens arranged to produce aesthetic effects. While table 236 presents locusts, crickets and other creatures in miscellaneous physical arrangement, table 239 artfully arranges butterflies in symmetrical formation, their labels moved down to the bottom of the page to create space for an attractively harmonious pattern. Such arrangements reflected a belief in the inherent beauty of nature, which naturalists believed derived from its divine origin. By curating his insects in this artful manner, Sloane cast himself not merely as a conscientious contributor to animal taxonomy but as a pious exhibitor of the aesthetic splendour of God’s creation.46