7

Creating the Public’s Museum

FOR THE IMPROVEMENT, KNOWLEDGE AND INFORMATION OF ALL PERSONS

On 11 January 1753, Sloane died at Chelsea Manor, three months short of his ninety-third birthday. His longevity was a testament to his self-discipline and, as we have seen, proved vital to his career as a collector. At his memorial service, carried out with ‘great funeral pomp’ at the family vault at Chelsea Parish Church, where Lady Sloane also lay buried, Zachary Pearce, Lord Bishop of Bangor, delivered his eulogy to a ‘crowded audience’. Bangor read from the ninetieth Psalm; his theme, he said, was ‘ye uncertainty of human life, & ye advantages of a good one’. Sloane had suffered no pain, he observed, nor had the ‘pleasures of conversation’ forsaken him even at the end. His devotion to Christian charity was manifest in the ‘multitudes of lives’ he had saved while a doctor and, as one of the learned world’s most ‘diligent searchers of nature’, he was revered at home and abroad with ‘lasting marks of esteem from crowned heads as well as private persons’. Bangor emphasized that Sloane’s acquaintanceship, a mark of the man, cut strikingly across all ranks of society: ‘from ye throne to ye shop, thro’ all ranks & conditions of men, he met with that respect & encouragement wch he merited.’ This universal friendship was the foundation of his universal collection. ‘In no age either pass’d or present, in no country either distant or near, did ever (perhaps) the world see such an almost universal assemblage of things unusual & curious, of things ancient & modern, of things natural & artificial, brought together from almost all times, & almost all climates.’1

The bishop attributed solemn religious purpose to this legacy. Sloane had been determined, he said, ‘that ye wisdom & goodness of ye great author of nature might be ye more plainly seen, [where] so large a part of his works were collected & in one place so abundantly displayed to view’. Glossing over their restricted accessibility, and echoing the Prince of Wales, he patriotically insisted that they constituted a public work that brought ‘honour to the nation’. Sloane’s treasures were a distinctively modern triumph, on a scale unknown in antiquity, outstripping even the treasures of the Roman Empire as catalogued by Pliny: ‘what Pliny … never conceived the human genius would dare to undertake, we have seen accomplished; and it must warm the heart of every Briton, to remember that it was done in his own country.’ Echoing the prince once more, the bishop touted the collections as national treasures while stressing also Sloane’s personal glory. ‘The Chelsea collection affords, and all worthy men must hope that it will for ages afford, conviction of it, and make the name of Sir Hans Sloane immortal. That a treasure like to this never was amass’d together, is beyond a doubt: all that is call’d great in its kind in the whole world becomes contemptible in the comparison; nor can we imagine that such an one ever can be compil’d again, unless such another almost miraculous combination of causes should appear to give it origin.’2

Within days of Sloane’s death, the London gazettes were buzzing with rumours about his will and the fate of the collections. One reported that they were worth £50,000 but might be offered to George II for the reduced sum of £20,000. Another valued them at £200,000 and spoke of the use of ‘two covered carriages belonging to his Majesty’ to deposit the more valuable items in the Bank of England for safekeeping. ‘Nothing so fully displays the grandeur of [Sloane’s] mind as his immense and rare collections,’ which were ‘perhaps the fullest and most curious in the world’; one might ‘venture to proclaim it the most valuable private collection (perhaps publick one) that ever has yet appeared upon Earth’. Like the Bishop of Bangor, gazette writers stressed the collections’ public pedigree. ‘These treasures, though collected at his private expence, have not been appropriated to his own pleasure alone’ because ‘mankind has enjoyed the benefit of them.’ Sloane’s Britishness also became a source of pride, if ambiguously so. His ‘native country’, it was said, was ‘proud of the honour of giving birth’ to him. But was this a reference to Ireland? The London Evening Post did mention Sloane’s Irish background but only as a yardstick to measure how far he had come from his provincial origins. He was ‘born at Killelagh in the County of Downe and Kingdom of Ireland’ but ‘his thirst after knowledge tempted him to remove from thence in his youth, in order to employ his talents in a more extended scene of life.’3

Bequeathing the collections to create a public museum was a novel and complex proposition, not least because the very notion of the public was itself in flux. In early eighteenth-century Britain, the term was mainly associated with the state, its apparatus and its officers rather than the ‘general public’ or the people at large. But the notion of ‘public opinion’ as an autonomous and legitimate political entity was taking on new force, even though its source proved hard to specify. For some commentators, public opinion derived from ‘the people’, yet whether they should be regarded as the moral bedrock of the nation or an unreasoning mob was a matter of debate. Members of the governing class grew alarmed as they perceived the potential of public opinion to destabilize political and economic life. ‘There cannot be a more dangerous thing to rely on, nor more likely to mislead one,’ John Locke had written in 1689 despite his endorsement of the right of rebellion in the Glorious Revolution, ‘since there is so much more falsehood and error amongst men, than truth and knowledge.’ On this view, popular opinion was less something for governments to follow than to shape through the skilful propaganda of writers like Daniel Defoe, who sometimes worked for the government as well. According to the philosopher Jürgen Habermas, however, the decades around the turn of the eighteenth century witnessed the emergence of the ‘public sphere’ as an arena of debate separate from and critical of government, thanks to the flourishing of both coffee houses and print culture.4

The idea of a public museum had a number of precursors – depending on how both ‘public’ and ‘museum’ are defined. Versions of some such institution can be traced back as far as ancient Alexandria. Unlike the courtly collections of aristocrats and royal families, church treasuries in medieval Europe regularly put relics and other objects on display before entire congregations. Several European collections were public, moreover, in the sense that they belonged to the state or were kept in official palaces. Natural history collections in Bologna were sometimes housed and exhibited in civic buildings by the seventeenth century; so too were the art and antiquities collections of the Capitoline Museum on the Campidoglio in Rome, which opened in 1734. Tsar Peter the Great of Russia pursued an active programme of public exhibition, albeit as a form of absolutist enlightenment, issuing proclamations in 1704 and 1718 demanding that all ‘monstrous’ births be sent to the St Petersburg Academy of Sciences, where the peasantry might be educated to see them as natural phenomena rather than demonic portents. In Paris, to celebrate the king’s art collections and help mould the national taste in painting, the Luxembourg Palace opened its galleries to visitors on selected nights beginning in 1750.5

In England, Charles I’s execution in 1649 occasioned a radical redistribution of royal property when commoners snapped up the headless king’s art at auction to raise money for the Republic, though many of these works were given back after the Restoration. Of more lasting significance was the opening of the Ashmolean Museum in 1683 at Oxford, which included the collections amassed by the Tradescant family. Admission to the Ashmolean was not restricted by class or limited to personal invitations but open to any visitor who paid the entrance fee. This made it among the most accessible collections in Europe, although for some the admissions policy was a distressing commercialization of the gentlemanly code of museum-going. Zacharias Konrad von Uffenbach was woefully put off by the spectacle of commoners in the collections in 1710: ‘it was market day and all sorts of country-folk, men and women, were up there … as we could have seen nothing well for the crowd, we went down-stairs again and saved it for another day.’ ‘Even the women are allowed up here for a sixpence,’ he noted disdainfully; at Oxford’s Bodleian ‘peasants and women-folk … gaze at the library as a cow might gaze at a new gate with such noise and trampling of feet that others are much disturbed.’ Public audiences for collections violated Uffenbach’s sense of scholarly civility as though a sacred inner sanctum, defined by class and gender as much as learning, had been defiled by a swinish multitude.6

In London, Sir John Cotton had bequeathed his manuscript collection to Parliament in 1700, but it lacked a proper home for decades, nearly burning to a crisp in 1731 in a fire at Ashburnham House. The Royal Society Repository had been curated by the distinguished naturalist Nehemiah Grew early on but was languishing by the eighteenth century. Sloane tried to revamp it after becoming president, but it was his own museum that served as the model of expert management, not vice versa – a group of Fellows visited him in Bloomsbury in 1733 to ‘better judge what may be proper to be order’d in the Repository’. Traffickers in rarities, meanwhile, had taken the lead in setting up commercial curiosity shows. These included the impecunious Claudius Dupuys who sold rarities to Sloane but also displayed them for money. In Chelsea, Sloane’s former servant James Salter ran what became the most popular cabinet of curiosities in eighteenth-century London, and which Sloane himself reportedly visited on a regular basis after his retirement. Exoticizing his name to entice visitors, Salter baptized his establishment Don Saltero’s Coffee House, in which he set aside a space called the ‘Coffee Room of Curiosities’. Here, customers drank and smoked and paid to see his rarities. The ubiquitous Uffenbach was impressed: ‘standing round the walls and hanging from the ceiling are all manner of exotic beasts,’ he observed, ‘such as crocodiles and turtles, as well as Indian and other strange costumes and weapons.’ To him, Saltero’s was a bona fide museum that offered real knowledge of strange new worlds.7

Others begged to differ. ‘I cannot allow a liberty he takes of imposing several names … on the collections he has made,’ Isaac Bickerstaff complained in the Tatler, doubting that Salter possessed either the knowledge or the honesty to be truthful about his wares. On the one hand, many of Salter’s objects possessed an impeccable pedigree, coming from virtuosos including Sloane himself, among them one of Sloane’s manatee straps – the banned Jamaica slave whip. Salter even published a catalogue in several editions trumpeting his inventory in suitably learned style. On the other hand, he indulged in low humour that suggested parts of the collections were mere jokes. His catalogue listed ‘a starved cat, found many years ago between the walls of Westminster Abbey’ and dealt in bankable anti-Catholic jibes by describing such relics as ‘the pope’s infallible candle’. Like the Ashmolean, the mixed reception Don Saltero’s occasioned shows how the reputation of curiosity collections remained decidedly chequered in the first half of the eighteenth century, poised between exotic museology and commercial tomfoolery. In any event, no collection, either in Britain or on the continent, was yet the property of a nation that granted free right of access to its citizenry as a matter of principle.8

Sloane’s own design to create a posthumous public museum appears to have evolved gradually. By 1700, he had started to buy books as a collector rather than for his own personal use; by 1707, he had begun to organize his correspondence with a view to posterity (this was no mean feat: one estimate puts his total number of correspondents at 1,793). That same year, he commended a plan to unite the Royal Society with the Cotton and Royal Library collections. He was thus publicly or at least institutionally minded from early on, at a time when there were effectively no national institutions to consolidate the many different private collections in the country. Contemporaries likewise came to regard his private museum as a repository of record. When in 1725 the horned lady of Pall Mall finally shed her famous growth, the London Journal announced its dispatch to Sloane’s museum ‘to be deposited amongst his other curiosities’ as a logical matter of fact. When the Leeds antiquarian Ralph Thoresby died that year, Thomas Hearne immediately urged to their mutual friend Richard Richardson that Thoresby’s things should ‘fall into good hands’ – ‘methinks they might be proper to be joyn’d with Sir Hans Sloane’s’ – no doubt mindful that Sloane had already collected the Courten and Petiver collections and several others. By 1725 Sloane, too, had begun to speak of himself as a public collector, voicing his hope that acquiring Petiver’s specimens would ensure they would be ‘preserved and published for the good of the publick’. A number of visitors to Sloane’s museum had also contributed to his collections over the years. In all these different ways, Sloane’s collections assumed an increasingly public profile as time went by.9

It was only in 1738–9, however, that Sloane considered his legacy in earnest as his health started to decline. ‘[I] begin to think of my affairs other ways than I have done,’ he wrote at age seventy-eight. He was not an aristocrat by birth and lacked a male heir. This meant that he was free from the conventional preoccupations of the nobility, who often sought to maintain the family name by ensuring their possessions passed to their children, but also that he was burdened by the concern, no doubt stemming from the prejudices of the time, that his two daughters Sarah and Elizabeth would not make appropriate custodians of his museum. Nor, if he could help it, did he wish to entrust his collections to the royal family or to an academy or learned society in Britain (the poor state of the Royal Society’s Repository may have dissuaded him from any such course), though all these options lay open before him. Instead, an original vision took shape in his mind: the foundation of a public museum. After a serious bout of illness in 1739, he focused his thoughts and began drafting a will to offer his collections to the nation according to a careful set of conditions.10

Testimony from James Empson, Sloane’s closest curatorial assistant, sheds light on how the project of a public museum coincided with Sloane’s personal desire for immortality. Some of the more grandiloquent collectors of the Renaissance had taken to styling themselves in the image of Narcissus, the Greek youth who fell in love with his own reflection. The love of fame was not necessarily the sin Sloane’s critics charged; in fact, it was arguably a civic necessity. Eighteenth-century commentators made a nice distinction between celebrity, which they defined as fleeting renown achieved during but not outlasting one’s lifetime, and imperishable fame (fama) as a noble and fitting reward for great works, usually military valour or literary achievement, which would inspire posterity to virtuous emulation. The idea of keeping Sloane’s entire collection together held great personal significance too, since collectors were haunted by the possibility that their collections would be dispersed, their labours squandered and their memory lost to posterity. Preserving collections whole was thus essential to preserving the memory of the collectors themselves. Empson championed Sloane’s cause after his death. It was the ‘duty’ of his executors, he stated in 1756 as one of them himself, and ‘in justice to his memory’, to prevent any part of the collection from being detached ‘from the whole’ and to ensure that it be ‘preserved and continued intire in its utmost perfection and regularity’. ‘Having been with the deceased to his last moments,’ he recalled, ‘[I] can positively assert, that one of his greatest inducements for disposing of his so extensive and large collection in the manner he has done, has been that his name, as the collector of it, should be preserved to posterity; far from being ever willing, that it should be eclipsed, or render’d less conspicuous by his collection being mixed with other matters or receiving an addition from other things.’ Embedded in Sloane’s audacious public gambit of a universal museum that surveyed the creation was the provincial Ulsterman’s personal ambition that his name should live for ever.11

This dual design of public and personal immortality was no departure for Sloane but the logical extension of a career advanced at almost every step by the intersection of public and private interests and the inextricability of personal and institutional lives. ‘I have seen the British Museum,’ the fictional Squire Matthew Bramble later declared in Tobias Smollett’s novel The Expedition of Humphry Clinker (1771), ‘which is a noble collection, and even stupendous, if we consider it was made by a private man, a physician, who was obliged to make his own fortune at the same time.’ To call Sloane ‘a private man’, however, fails to capture either the highly public career he enjoyed as a physician and naturalist or the extent to which he assembled both his own fortune and his collections through a wealth of connections to public persons and institutions in an age of national consolidation and imperial expansion. Sloane had clearly seen himself as playing a leading role in British public life. Writing to the Abbé Bignon in 1737, for example, he praised ‘the genius’ of French state support for scientific expeditions that had measured the shape of the earth in Peru and at the North Pole, only to lament that in Britain it fell ‘among our nobles and persons of consideration and taste’ – above all himself – to back voyages such as Mark Catesby’s American expeditions by private subscription. When it came to such projects, Sloane and his associates were the British state. The contents of Sloane’s collections reinforce this view, as his papers often resemble those of a state more than those of a private individual, including descriptions of projects for legal and penal reform, insurance schemes, workhouses and highway and harbour repair. Just as Sloane’s banker Gilbert Heathcote had leveraged his private fortune to support both the Glorious Revolution and the creation of the Bank of England, Sloane now aimed to use his massive private collections to force the foundation of a public museum.12

Sloane’s will was published on his death in 1753. The care with which he had crafted it and its codicils suggests that the lessons of the bitter dispute over the Hamiltons’ contested Ulster estates he had witnessed all those years before had stayed with him. Having swallowed so many other collections whole, he understood just how easy it was for a lifetime’s work to disappear and so knew what to avoid: there would be no auctions, no sell-offs and no combinations with other collections. After stating his view that his museum was a ‘manifestation of the glory of God’ that should be used ‘for the confutation of atheism and its consequences’, the centrepiece of his final draft stipulated that it be accessible in the following terms: ‘I do hereby declare, that it is my desire and intention, that my said musaeum or collection be … visited and seen by all persons desirous of seeing and viewing the same … [and] rendered as useful as possible, as well towards satisfying the desire of the curious, as for the improvement, knowledge and information of all persons.’ To serve the ‘public benefit’, a museum housing his things should be located ‘in and about the city of London, where I have acquired most of my estates, and where they may by the great confluence of people be the most use’. Sloane’s use of the phrase ‘all persons’ suggests literally universal access: that any person who wanted to see the collections should be free to do so. However, he also invoked ‘the curious’, a rather ambiguous term in the eighteenth century. ‘The curious’ connoted learned gentlemen (and ladies) possessed of education, wealth and station but by mid-century might also suggest mere curiosity-seekers: those who paid to witness unusual or dubious spectacles in taverns and coffee houses. A related ambiguity lay in the distinction between what Sloane referred to as ‘seeing and viewing’ the collections and ‘rendering them useful’. These activities implied rather different functions for his proposed museum and divergent definitions of the public, leaving open to debate what the correct balance should be between mounting exhibitions for audiences and facilitating research by scholars.13

Sloane attached highly specific conditions. First, he did not offer his collections as a gift to the nation, as is often thought, but asked £20,000 for them. This amount was, he claimed, one-quarter of their actual value of £80,000. The proceeds would go to his two daughters. Second, because he could not be sure that the notoriously partisan Parliament would cooperate and embrace his terms, and because he was probably well aware of the neglect of the Cotton collection supposedly in their care, he devised the following contingency plans. If Parliament did not buy his collections within twelve months, they were to be offered, in order, to the scientific academies at St Petersburg, Paris, Berlin and Madrid, each having a year to decide (early versions of Sloane’s will had included the Royal Society, the University of Oxford and the Edinburgh College of Physicians, but he later ruled these out). Only in the unlikely event that there proved to be no takers at all were the collections to be auctioned off. This was bold. The threat of sending the collections abroad may have been strategic, but Sloane could not have predicted with certainty that it would succeed in forcing Parliament’s hand. Sending the collections overseas might in fact have been genuinely desirable in ways that reflected a significant ambiguity in their status: were they treasures that belonged first and foremost to Britain, or did they rather belong to the Republic of Letters and international learned society? Was Sloane ultimately more patriot or cosmopolitan? That he was a member of every foreign academy he listed as a possible repository for his museum points to the seriousness with which he contemplated moving his collections out of Britain (he continued to receive foreign honours until 1752, when the Academy of Sciences at Göttingen made him a member at the age of ninety-two). Indeed, he moved St Petersburg up the pecking order after his former curator Johann Amman assured him of the high quality of the Russian facilities. Selling to the Russians was exactly what some did, like the Dutch naturalist Albertus Seba, whose collections Peter the Great acquired in 1716. London was Sloane’s first choice, but keeping the collections and his legacy intact was in some ways as important.14

Sloane choreographed his own legacy from the moment he died, assembling an impressive group of friends to carry out his plan. He had drawn up a list of attendees for his funeral, each of whom was to be given a commemorative ring worth twenty shillings. He named four chief executors to be led by his grandson Lord Cadogan – the others were James Empson and his nephews William Sloane and Sloane Elsmere – as well as a set of trustees, who met soon after his death at Chelsea Manor. Numbering sixty-three in total, these trustees featured many prominent society figures, family members, friends and Fellows of the Royal Society – a cross-section of the elite public life Sloane had lived. They included John Heathcote, son of Gilbert Heathcote, and an East India Company director, a Bank of England director and the president of the Foundling Society; James Lowther, a South Sea Company director, the storekeeper of ordnance and the Foundling vice-president; General James Oglethorpe, the soldier and founder of Georgia; Joseph Ames, paymaster to the Scottish armed forces; Thomas Burnet, judge of the Common Pleas; Count Nicolaus Zinzendorf, who leased land from Sloane in Chelsea on behalf of the Moravian Church; the Duke of Northumberland, who sat on the Privy Council, and other officers of state such as Edward Southwell, secretary of state for Ireland; Sir Paul Methuen, formerly lord of the Treasury, lord of the Admiralty and secretary of state; the Bishop of Carlisle; and Horace Walpole, the writer and son of the prime minister.15

Walpole was among the most interesting because he was in fact highly sceptical regarding Sloane’s collections and because that scepticism embodied an important division in British culture between natural history and art collecting. ‘We are a charming, wise set,’ he wrote to his friend the diplomat Horace Mann of his fellow trustees in 1753, ‘all philosophers, botanists, antiquarians, and mathematicians.’ But he had better things to do. ‘You will scarce guess how I employ my time,’ he continued, ‘chiefly at present in the guardianship of embryos and cockleshells … [which Sloane valued] at fourscore thousand; and so would any body who loves hippopotamuses, sharks with one ear, and spiders as big as geese! It is a rent-charge, to keep the foetuses in spirits! You may believe that those who think money the most valuable of all curiosities, will not be purchasers.’ A few years later in 1757, in an ‘advertisement’ for a Catalogue and Description of King Charles the First’s Capital Collection of Pictures, Walpole outlined his personal hope that the new British Museum would inaugurate ‘a new aera of virtùe’ and inspire collectors to contribute to it for the good of ‘their country’, rather than see their collections dispersed by ‘straggling through auctions into obscurity’. Walpole held conflicting views on auctions: he frequented them avidly but also saw them as a threat to the social order, affording arrivistes quick climbs in status and threatening noble collections with dissolution. These fears were later realized when his father’s art collection at Houghton Hall – an expression, ironically, of Sir Robert Walpole’s own upward social mobility – was sold to Catherine the Great to pay off debts. Horace thought so little of Sloane because he evidently saw him as a parvenu peddling petty curios, bereft of true connoisseurship. Prizing the ‘fine arts’ rather than the merely ‘useful arts’ of natural history, his hostility was surely piqued by the vexed status of painting in British culture, due to longstanding associations with Catholic finery and princely corruption. Not until 1768 – after the British Museum had opened – would the Royal Academy be created and establish art galleries as an essential feature of public life. In the meantime, Walpole dreamed of the British Museum, not as the encyclopaedic museum Sloane envisaged, but as an inaugural national art gallery. Shamelessly hijacking Sloane’s legacy in his introduction to Charles I’s catalogue, Walpole transposed the dead king in Sloane’s place as the museum’s patron saint, lionizing him as ‘the royal virtuoso’ who had martyred himself to develop the national taste for art by suffering ‘rebellion and rapine’ by the ‘envious mob’ who stole his pictures.16

If the other trustees harboured similar reservations, they kept them to themselves. While parts of the collections sat in the vaults of the Bank of England for safekeeping, Sloane’s executors approached Parliament with his terms. The offer, however, did not automatically win assent from MPs: word came back that there was no money in the Treasury for the purchase. Serious advocacy was going to be necessary if Sloane’s collections were to be secured. So the trustees petitioned Parliament and succeeded in setting up a debate in the House of Commons on 19 March 1753. Empson, acting as their secretary, was among the leading witnesses called when the day came. The cost of running the museum unsurprisingly emerged as a key issue. Empson did his best to reassure the ministers that the tally would be far from exorbitant by itemizing the estimated salaries, for example, of each proposed member of staff. But scepticism concerning the purpose of the collections persisted, MP William Baker typically dismissing Sloane’s museum as ‘a collection of butterflies and trifles’.17

Fortunately for the trustees, they had allies in the Commons. Arthur Onslow, a Whig member and speaker of the House, took up the case for the creation of the museum. He included the still-pending fate of the Cotton manuscripts in the debate while Henry Pelham, an old friend of Sloane’s, took the opportunity to urge that the library of Robert and Edward Harley, the Earls of Oxford, already bequeathed to the nation by the Duchess of Portland, should also form part of any purchase. Given the general scorn for natural history, the addition of these manuscript collections may actually have helped to galvanize MPs’ interest. Political manoeuvring for partisan advantage was likely one important subtext of the discussions; collection building was often ideologically motivated. For example, Thomas Hollis was an avowed Whig and an advocate of American rights during the American Revolution who donated many books on political philosophy – specifically concerning republican political thought – to both the British Museum and Harvard College in Massachusetts. Sloane had long enjoyed close ties to prominent Whigs and it was Whig MPs who now championed his cause: Onslow, the member for Bristol, Edward Southwell, Jr (son of Edward and grandson of Robert Southwell, the secretaries of state for Ireland) and Philip Yorke. Sloane had named both Southwell and Yorke as trustees. These men may well have seen the collections as an instrument for promoting Whig politics since they could be taken to embody the traditions of Anglo-Saxon liberty: the Cotton manuscripts contained a copy of the Magna Carta that might be used as a potent vehicle to ground Whig claims to its legacy. Not that Whigs had a monopoly on such designs. The Tory and Jacobite Thomas Carte had argued for acquiring the Harleian manuscripts in the early 1740s because they were evidence, as he put it, of ‘the ancient rights and privileges of Englishmen … which our ancestors enjoyed’ – and which, by Tory implication, the Whigs had undermined.18

Thanks to the efforts of Onslow and his colleagues, Sloane’s executors eventually won the debate and the Commons voted to accept the terms of Sloane’s will. Parliament would oversee the creation of a public museum. The House of Lords passed the British Museum Act between discussions of a bill for preventing disease in cattle and the setting of a prize for discovering longitude at sea, and on 7 June 1753 George II gave his royal assent. Echoing Sloane, the act stipulated that the collections were ‘not only for the inspection and entertainment of the learned and the curious, but for the general use and benefit of the publick’. The precise form the new museum would take and the details of its terms of access, however, remained to be finalized. In return for keeping the collections together and making them available in London, Sloane’s executors accepted a series of changes imposed by Parliament, including the installation of officers of state as ex officio trustees (rather than exclusively retaining Sloane’s personal friends), among them the lord chancellor, the speaker of the House of Commons, the Archbishop of Canterbury and the several secretaries of state. How the new institution came to be baptized the British Museum, and by whom, is not known, but the choice of name was significant. It declared national possession of the collections, making their preservation and display a projection of national honour and power. For the most part these were British things not by origin but by ownership. As the author Edmund Powlett put it in his 1761 guidebook, evidently the first of its kind, the ‘Museum of Britain’ was ‘a lasting monument of glory to the nation’. The Sloane, Cotton and Harley collections would be brought together with the additional library of Major Arthur Edwards (by then joined with the Cottonian Library), the sum of £20,000 paid to Sloane’s daughters, and a regular revenue established to support maintenance, financed in part by investment in public stocks.19

The purchase of shares wasn’t the only form of organized gambling on which the museum was to rely. The bulk of the British Museum Act was in fact taken up by the scheme Parliament hatched for raising the £20,000 it owed Sloane’s daughters by means of a public lottery. It was thus not the allocation of state funds or far-sighted royal patronage that paid for the nation’s museum but the money ordinary folk were willing to stake on winning cash prizes by forking out for a ticket or two. The authors of the act were well aware that they were making a public virtue out of private vice, so they ordered a lengthy series of crimes and punishments for cheating, including imprisonment and even the death penalty in the event of tickets being forged. The hoarding of tickets was another major concern. Up to 100,000 were to be issued at £3 each, each drawn up by hand in duplicate, of which there was to be a sliding scale of 4,159 ‘fortunate tickets’, from a grand prize of £10,000 all the way down to 3,000 worth £10 each. The lottery draw eventally began in London’s Guildhall on 26 November 1753, and a total of £200,000 was given out in prize money afterwards.20

Even by the gamble-happy standards of the eighteenth century, the British Museum lottery was widely seen as scandalous. Parliament ordered an official review the month after it had been completed. One of the appointed lottery managers, Peter Leheup, stood accused of buying tickets in bulk and profiteering on their resale, allegedly making as much as £40,000. He was fined £1,000 and dismissed. A large number of tickets also appear to have been bought by an unidentified individual who adopted a variety of aliases. The gregarious City banker, financier and sometime art collector Samson Gideon reportedly obtained thousands of tickets even though he was allegedly in France at the time (a friend of Sir Robert Walpole’s, he was not indicted). Chicanery notwithstanding, £95,194 8s 2d comprised the net proceeds after expenses were deducted, to cover the purchase of the collections and a building to house them, pay Sloane’s daughters and make initial investments in shares. This was indeed a British museum. This new temple of the arts and sciences, with its promise of scholarly and practical enlightenment, had been erected on the basis of a private fortune, a vast web of imperial connections, wrangling over money and the national addiction to betting (Plate 42).21

Since Chelsea Manor was deemed too far from the centre of London and too small to accommodate large numbers of visitors or indeed the collections themselves (Sloane had taken to using his basement for storage), it was decided that a larger and better-placed site was needed. The then privately owned Buckingham House (now Buckingham Palace) was one option but was thought too expensive at £30,000, so Montagu House, originally designed by Sloane’s Royal Society colleague Robert Hooke and rebuilt after a fire in 1686, was acquired for the bargain price of £10,000 in 1754–5, with a subsequent £8,600 spent on restoration and repair. As chance had it, the building was situated on Great Russell Street, just a few steps from Sloane’s original residence off Bloomsbury Square, on the edge of the city and flanked by open fields. In an especially strange coincidence, Montagu House happened to be the former residence of the widowed Duchess of Albemarle – the duke’s wife and Sloane’s former patron – who had gone on to marry the Duke of Montagu, bizarrely, only after the duke agreed to impersonate the Kangxi emperor to indulge certain exoticist fantasies of hers, or so the story went. The Sloane, Cotton and Harley collections were all carefully checked, as well as Sloane’s catalogues, which were found to be ‘exactly answerable’ to the objects they described. Library books still out on loan at Sloane’s death were called back and the trustees began to set up the building and its staff. Early in 1756, the natural philosopher, inventor and wily promoter of magnetic compasses of his own design Gowin Knight secured the key appointment of librarian and headed up his own staff of three, including Empson and the physicians Matthew Maty and Charles Morton. There was much to do: new catalogues to be compiled, wooden cabinets to install, shares to buy and salaries to fix. The physical environment needed work too, since Montagu House turned out to be damp and cold (the source of endless complaints), so the number and cost of candles and coals to light and heat the place needed proper calculation. Many of the decisions were to be overseen by Knight, but the ambitious magnetizer soon overreached, with the museum’s standing committee censoring him for choosing his own workmen to effect repairs without consulting them. There was also trouble with some of those who lived on the premises – not the maids or curators but the porters who by all accounts liked their liquor rather too much.22

As preparations progressed, the museum staff began to consider what kind of display would be appropriate for presenting the nation’s museum to the general public. A number of Sloane’s duplicates were disposed of, some claimed by Sloane’s daughter Sarah; the plates of the engravings from the Natural History of Jamaica also went to the family, as did a few select objects, perhaps for sentimental reasons. Knight, Empson and their colleague the natural philosopher William Watson decided to rearrange the collections. Keeping them together, they determined, did not mean they could not be reorganized. ‘However so much a private person may be at liberty arbitrarily to dispose and place his curiosities,’ Empson told the Board of Trustees, ‘we are sensible that the British Museum being a public institution subject to the visits of the judicious and intelligent, as well as curious, notice will be taken, whether or no the collection has been arranged in a methodical manner.’ Sloane’s approach to display was with polite harshness discarded: the change from private to public museum entailed a shift from mere ‘curiosity’ to ‘judiciousness’. Plans drafted by Knight and early descriptions of the museum show that the curators moved towards a more didactic scheme modelled on the Chain of Being, according to which the cosmos was structured by a hierarchy of being passing from God down through the angels to human beings, animals, plants and minerals. Sloane’s emphasis on variety within object categories was now dismissed as lacking the coherence and harmony deemed appropriate for a public museum. Knight explained how Sloane’s collections could instead ‘be properly classed in the three general divisions of fossils, vegetables, and animals’ and made to exhibit nature in its ‘gradual transitions’ as it ‘ascended to the next degree of being’, so that ‘the spectator will be gradually conducted from the simplest to the most compound & most perfect of nature’s productions.’23

Interestingly, contemporary observers linked museological order with social order. Some feared that free access to the collections might inspire dangerously emboldened passions in the common people. In 1756, after a preview tour of Montagu House, the Berkshire essayist and Bluestocking Catherine Talbot recorded a singular vision that had gripped her. She had been, she wrote, ‘delighted’ to see ‘valuable manuscripts, silent pictures, and ancient mummies’ in the museum but ‘in another reverie’ had imagined ‘the books in a different view, and consider’d them (some persons in whose hands I saw them suggested the thought) as a storehouse of arms open to every rebel hand, a shelf of sweetmeats mixed with poison’. It is not clear exactly whom Talbot saw handling the collections, but in her premonition free access raised the spectre of civil unrest. She was not alone in such presentiments. The previous year, the antiquarian and museum trustee John Ward had objected to ‘appointing public days for admitting all persons’ as giving free rein to ‘the mob’. ‘If the common people once taste of this liberty … it will be very difficult afterwards to deprive them of it.’ The only visitors should be those who ‘will conform to the rules & orders’, as most ‘ordinary people will never be kept in order [and] will make the apartments as dirty as the street’, wreck the furniture and gardens ‘& put the whole oeconomy of the museum into disorder’.24

Sloane’s provision of free universal access was causing serious consternation. To some the very idea was highly threatening. From early on, the trustees had envisaged different ranks of person enjoying unequal degrees of access to the different parts of the museum. Lord Cadogan urged in 1756 that admission actually be denied to ‘very low & improper persons, even menial servants’, while early proposals for ‘making the collections of proper use to the publick’ sought to parse and narrow Sloane’s call for universal access ‘to prevent as much as possible persons of mean and low degree and rude or ill behaviour from intruding on such who were designed to have free access to the repository for the sake of learning or curiosity’. The curators Charles Morton and Andrew Gifford commented in 1759 that ‘from the mechanic up to the first scholar and person of quality in the kingdom, who come all whetted with the edge of curiosity … there are hardly any two that apprehend alike, or do not require the same thing to be represented to them in different lights.’ Gowin Knight, jealous of his fiefdom, argued for barring persons of ‘no distinction’ from the library, contending that they posed a threat to the collections and that scholarship was a public mission best served by the learned only. ‘The public’ may have been a universal category but it was far from a uniform reality.25

Turning a private cabinet into a public museum meant bringing people closer to things but also keeping them away from them. New rules recorded by Thomas Birch mandated that all medals, gems and ‘other small curiosities of a like nature, in the repository, [should] be locked up in drawers, with glasses or wires over them, thro which they may be seen; but not taken out, and intrusted in the hands of any person, unless in the presence of the keeper or his assistant’. Other objects were also to be put ‘in wainscot presses or cases of like dimension and with the like guard of brass wire in the front’. According to Knight, the museum’s primary purpose was ‘for the use of learned and studious men, as well natives as foreigners’, although because it was funded by public money access should be ‘as general as possible’. The emphasis had shifted subtly but surely from Sloane’s insistence that ‘all persons’ be admitted to the museum to the prioritization of good conditions in which scholars might carry out their researches. Where Sloane had given his private guests objects to hold, touch and even taste, the public were to be extended no such trust. ‘In viewing the contents of the cabinets no one is to be permitted to lay their hands on any thing,’ Knight stated categorically. Further regulations were laid down for the behaviour of visitors, who were to be admitted only in appointed groups. In death as in life, Sloane collected not just a world of things but a world of people: universal access to the museum would swell the numbers of people who saw his collections beyond any historical precedent and make them the most famous the world had ever known. Montagu House’s new locked cases and drawers were, however, a sign of the ambivalence with which his successors prepared to greet the public as they passed through the doors of the British Museum for the first time.26

ENTERING THE BRITISH MUSEUM

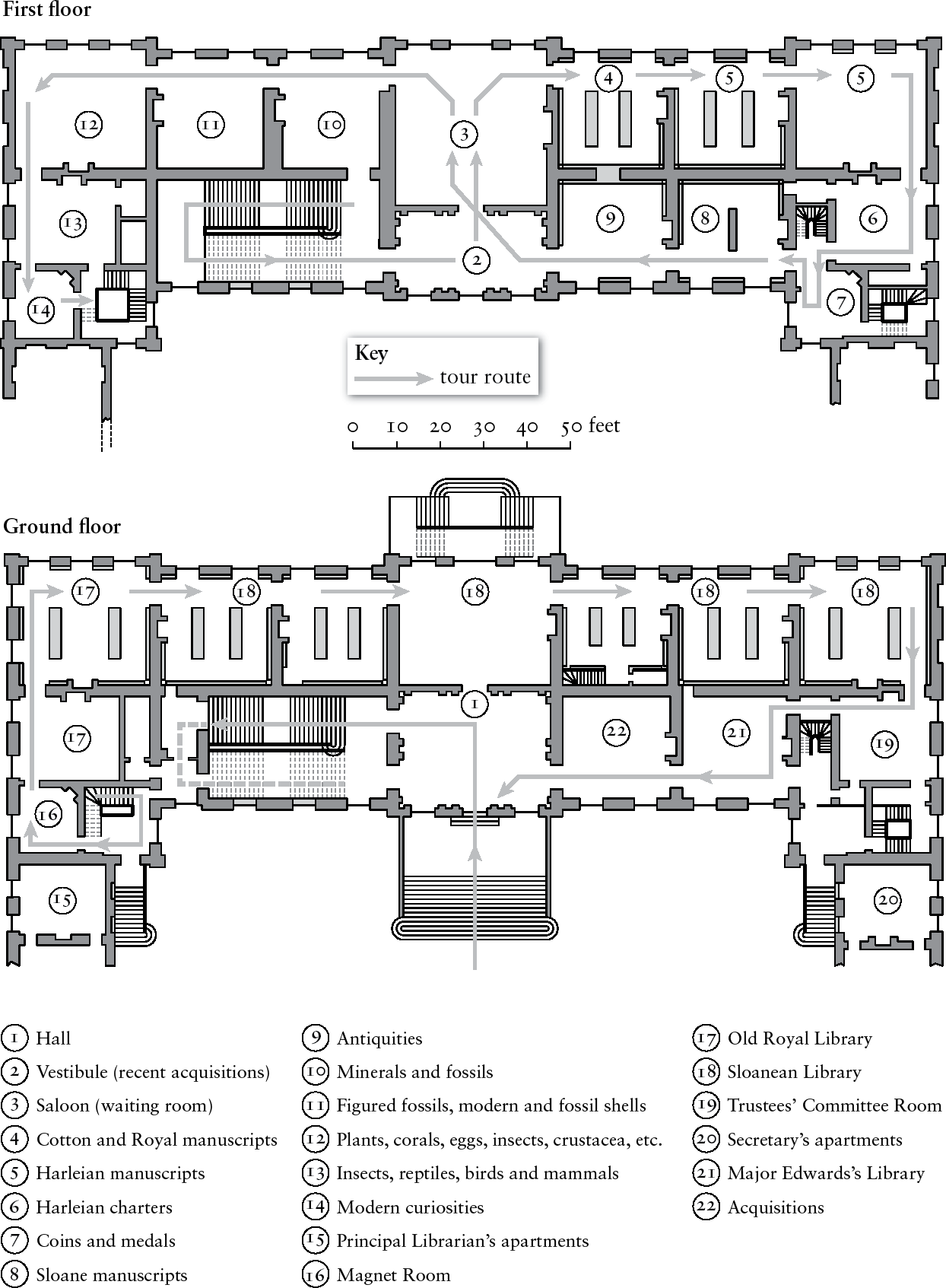

The British Museum opened on Monday 15 January 1759, six years after Sloane’s death, almost to the day. Admission was free but had to be requested in advance in writing, a requirement that kept numbers down. On the appointed day, visitors congregated at the museum gates on Great Russell Street where they were met by one of the porters, who ushered them across the courtyard (opposite). Initially the tours were small – two groups of five were admitted together; a few years later this was expanded to fifteen. Each visit lasted two hours, originally on Mondays and Thursdays only. The museum’s managers decided that the majority of visitors would have little interest in the reading room, so most time would be spent in the natural history collections under a watchful curatorial eye (here). By far the best account of the early tours comes from the 1761 guide published by Edmund Powlett, The General Contents of the British Museum. Little is known about Powlett. He did, however, explain that his book was a collective effort based on contributions from ‘several gentlemen, who gave me notes they had taken on viewing it’, as well as ‘a lady, who gave me some curious remarks on the recent shells’. Powlett especially thanked one unnamed source – possibly Empson – ‘who greatly assisted me, which he was the more qualified to do, as having been intimately acquainted with Sir Hans Sloane’. His aim was to direct the reader ‘to apply his particular attention to that part of the museum that suits his taste’, since ‘his curiosity will be much more gratified, than if he wanders from object to object’.27

Entering Montagu House in all its refurbished glory, visitors were greeted by fine French frescoes above their heads; a stone from the Appian Way in southern Italy and fragments of other Roman landmarks at their feet; the skeleton of a unicorn fish; a buffalo head from Newfoundland; and various stones bearing Latin inscriptions. On the ground before them, they beheld several hexagonal pillars from near Coleraine, County Down, taken from the Giant’s Causeway – probably the samples Sloane had acquired back in the 1690s. The tourists then turned left through a stone archway towards the grand staircase and moved past a series of painted mythological scenes, Roman military tableaux, Bacchanalian revels, French landscapes and architectural scenes – holdovers from Montagu House’s original classical design. On going upstairs, they filed past ‘the busto of Sir Hans Sloane, on a pedestal’, but there was little time to dwell. Entering the first chamber on the first floor, they saw an Egyptian mummy, probably the recent gift of the Lethieullier family (London merchants who were among Sloane’s trustees), followed by a medley of Sloaneana: corals, wasps’ nests, a sample of ‘brainstone’, a stuffed flamingo and assorted animals coiled into spirit-filled jars. Turning left, they entered the grand saloon and were invited to sit and rest awhile on handsome Virginia walnut chairs. Warmth could be felt from nearby fireplaces. There were more paintings and the wax model of a sculpture depicting the tragic Trojan priest Laocoön. The museum’s idyllic gardens were visible through the windows, with the inviting greenery of Hampstead and Highgate off in the distance.28

Now the real tour of the museum’s three departments began. First, manuscripts and coins. The manuscripts were divided into four parts, each housed separately: Sloane’s collection, the library donated by George II just prior to his death in 1760, and the Cotton and Harley collections. The entrance had a portrait gallery including likenesses of kings and queens, Oliver Cromwell, John Locke, William Shakespeare, Francis Bacon, Sloane’s portrait of William Dampier, the famed anatomist Andreas Vesalius and the eminent scholar Anna Maria von Schürmann. There were busts too of Homer, Peter the Great, Ulisse Aldrovandi and monarchs from Edward III to Charles II (but no James II). The manuscripts were stored in newly made cabinets and presses wrought of wood and wire, ornamented with still more busts. Learning involved climbing: stepladders and staircases were everywhere. Most of the manuscripts were folded away in drawers, although Cotton’s copy of the Magna Carta was prominently displayed in its own glass case – the ‘bulwark of our liberties’, Powlett called it. Harley’s remarkable collection of almost 8,000 manuscripts took up three chambers by themselves, including antique copies of the Bible, the Qur’ān and the Torah. The next room contained the Sloane manuscripts: not the most ancient but of great value for natural history and medicine. Cabinets holding Sloane’s thousands of coins and medals filled the next chamber as well.29

The museum’s second department housed ‘artificial and natural productions’ in a series of chambers, drawn mostly from Sloane’s collections of antiquities and miscellanies. There were artefacts from Mexico and Peru and the model of a Japanese temple; baskets made out of bark; ‘hubble-bubbles’ (similar to hookah pipes) and tobacco pipes from America; drums from China; amulets and charms in Arabic and from ancient Rome; musical instruments, scientific instruments, instruments of punishment and instruments of sacrifice; classical sculptures; and ‘American idols’. These were followed by natural specimens: fossils, vegetables and animals arranged in a sequence to show off the ‘chain of gradation’, as Gowin Knight had envisioned, all arrayed in yet more exquisite furniture: glass wall cabinets made from deal and mahogany, with table cases and portable show-tables of mahogany and glass. Sloane’s minerals and fossils were laid out in a chamber of their own, their cases labelled in Latin. In the next room were shells, more minerals, bezoars and a curiously encrusted skull fished out of the River Tiber in Rome. These were followed by plants and insects, woods, fruits and barks packed into drawers by the thousands – Sloane’s vegetable substances. There was silk grass, Indian cotton and Sloane’s Jamaican lagetto; virtual reefs of coral; wasps’ nests; and countless animals in jars. Rings, intaglios and seals were spread out in glinting variety on large tables, just as they had been for the Prince and Princess of Wales at Chelsea.30

The final chamber contained ‘modern curiosities’. These included items ranging from glass cups fashioned in imitation of china to ‘articles in great esteem among many Roman Catholics, as relics [and] beads’, as Powlett diplomatically put it, ‘and some models of sacred buildings’, as well as crucifixes placed by miners at the entrance to mines in those parts of Germany ‘where the Roman Catholic religion prevails’. There were Native American feather crowns and Wampum beads; scalps and specimens of cassava poison; European bronzes and ivories; Engelbert Kaempfer’s portable Buddhist shrines; samples of money from the East Indies; Chinese deities done in bronze and congee; forks and counting beads; japanned boxes and vessels; Chinese porcelain and tea leaves; a ‘cyclops pig, having only one eye, and that in the middle of the forehead’; and the horn of the horned lady, with her picture, which had made it from Pall Mall to Sloane’s and now the British Museum. Finally, visitors made their way back downstairs, past a series of paintings and canoes. Gowin Knight showed off some of his compasses and magnets before admitting guests to the library, although only for a brief peep at the third and final department: that of printed books (Sloane’s included) laid out in a sequence of six rooms, together with Sloane’s herbarium and a series of maps spread out on tables. Without actually entering the reading room, most visitors were informed that their two hours were up, escorted to the museum gates and bid good day.31

In some respects, little had changed since the private tours Sloane had conducted in his Bloomsbury townhouse. Curiosities still abounded in riotous variety from Roman skulls to cyclops pigs, with surprising juxtapositions of horned ladies and fine Chinese porcelain. Sloane’s hybrids of art and nature were still on show like his coral-encrusted bottles and timbers from the 1680s. Mysteries of nature remained too. The Museum Britannicum, a guide published by the Dutch artists Jan and Andreas van Rymsdyk in 1778, featured an alluring painting of Sloane’s coral hand, which the authors thought ‘very curious’, noting that the manner of coral’s generation was not yet determined by the naturalists (here). Nor was the art of recounting curious tales entirely neglected. Powlett told the story of a ‘model of a fine rose diamond’ of nearly 140 carats that had originally been owned by Charles the Bold until his defeat at Nancy in 1477, when it had fallen ‘into the hands of a common soldier’ who picked it up on the battlefield but who, in his ignorance, sold it off for a pittance. The diamond then found its way to one of the grand dukes of Tuscany, the Medici family and the Emperor of Germany before somehow winding up in the British Museum. The Rymsdyks also repeated exotic object tales, describing for example how ‘black women’ used the hairballs Sloane liked to collect for medical purposes (and which they illustrated for their beauty) as deadly poisons.32

Powlett also encouraged his readers to keep up the tradition of visitors contributing to the collections. ‘I am not without hopes that the time may soon come, when every public-spirited collector’, he wrote, ‘will deposit the produce of his labour in this most valuable cabinet.’ Numerous gifts are recorded in the early years of the museum archives, including letters to James I, a fourteenth-century herbal, exotic plants for the garden, a hornet’s nest from Yorkshire, an electrostatic machine, books from China and a human heart preserved in wood found in the hollow pillar of a Cambridgeshire church. As a result, there was more than ever to see. Given the ‘almost infinite number of curiosities’, Powlett lamented, it was ‘impossible for [tour guides] to gratify every particular person’s curiosity’. ‘I am sorry to say, it was the rooms, the glass cases, the shelves, or the repository for the books in the British Museum which I saw,’ the German author Karl Philipp Moritz complained about the visit he made some years later in 1782, ‘and not the museum itself, we were hurried on so rapidly through the apartments.’ He spoke of ‘rapidly passing through all this vast suite of rooms, in a space of time, little, if at all, exceeding an hour … just to cast one poor longing look of astonishment on all these stupendous treasures … in the contemplation of which you could with pleasure spend years’. That ‘a whole life might be employed in the study of them – quite confuses, stuns, and overpowers one’.33

Powlett’s description also suggests substantial continuity with Sloane’s emphasis on the collections as a survey of the world’s resources and commodities. American pipes served to ‘discover the industry, genius, and manners of the inhabitants’ of the New World, he advised. ‘Marble is a hard opake precious stone,’ he explained, ‘does not strike fire with steel, yields easily to calcination, and ferments with, and is soluble in acid menstrua.’ ‘Alabaster’, he clarified, ‘is of the same nature as marble, but of one simple colour, more brittle, softer, and, when cut into thin plates, semi-transparent.’ He pointed out how different cultures valued different commodities – hence the high price of ginseng in the Indies but not in Europe, and the great sums Wampum beads fetched in America, while the Chinese valued only their own handicrafts and shunned foreign goods. Imagining their readers as would-be connoisseurs, the early guides warned them about avoiding fraud and even taught them how to do so. The Rymsdyks went so far as to describe practical techniques on ‘how to know good pearls’ from bad by the use of microscopes. While curiosities offered lessons about commodities, visitors to London saw the city itself as a giant commercial Wunderkammer. On the same trip during which he toured the British Museum, Moritz promenaded on the Strand and admired the way that ‘paintings, mechanisms, curiosities of all kinds, are here exhibited in the large and light shop windows, in the most advantageous manner’, resembling ‘a well regulated cabinet of curiosities’.34

Powlett’s guide kept Sloane’s hostility to magic in full view as well, once again singling out amulets and talismans as examples of the superstitions of backward ancient and foreign peoples. He spoke, vaguely yet pointedly, of ‘several small amulets … which in Egypt the blind superstition of the inhabitants prompted them to wear about their persons, as charms, or preservatives against bad fortune’. He described Sloane’s Sámi drum as being ‘of the same sort as those used by their enchanters, by the help of which … they were enabled to raise mighty tempests’. There was an ancient Roman charm with the head of the god Mercury and ‘Turkish talismans, or charms, with Arabic inscriptions, being generally a sentence of the Alcoran’, not unlike the ones Ayuba Suleiman Diallo had translated for Sloane. ‘In these the superstitious among the Mahometans have great faith, and rely much on their power’ against spirits that ‘they believe are continually hovering about the world’. There were bezoars used for protection by ‘credulous people’ and Sloane’s ‘Scythian Lamb’, in reality ‘the root of a plant much like [a] fern’. ‘A very little help of the imagination makes it altogether a tolerable lamb,’ Powlett sarcastically allowed.35

Flush with such contrasts between superstition and enlightenment, Powlett did not stop there. He insisted that the museum’s collections had a special power – the power to civilize those who saw them. ‘Learning was for many ages in a manner buried in oblivion,’ he stressed, intimating a grand if rather hazy narrative of progress, and ‘a dark ignorance spread itself over the face of the whole earth’, a period during which real innovations in science, medicine and technology had been foolishly derided as ‘magic’. In contrast to this epoch of ‘blind infatuation’ and ‘obstinate prejudice’, the British Museum displayed ‘the progress of art [technology] in the different ages of the world’ for all to see, ‘exemplified in a variety of utensils each nation in each century has produced’. The contemplation of such tools, Powlett urged, would ‘prevent our falling back again into a state of ignorance and barbarism’. ‘Many things deemed of small value by a vulgar observer, when viewed by the learned, are found to be of abundant use to science,’ he confidently observed. By inculcating lessons that enabled visitors to distinguish treasures from baubles, the museum would prove a mighty bulwark against the ‘iron hand of ignorance and superstition’.36

Who the ‘ignorant’ and ‘barbarous’ were exactly, Powlett did not say. For decades, however, Europeans had used such language to pour scorn on the cultures and belief systems of foreign peoples they encountered as they built up their empires. Powlett, moreover, was writing during a period of dramatic British gains when the resonance of these terms intensified significantly. Although the Seven Years’ War began with a number of setbacks and was not formally concluded until the Peace of Paris in 1763, the British scored decisive victories against the French in the so-called annus mirabilis of 1759 – the same year the British Museum opened. By the time the war ended, a largely maritime power that had struggled to emulate its Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch and French rivals in both the Atlantic and Indian Oceans had been transformed into the greatest territorial empire enjoyed by any European nation. After defeating France, Britain set about governing India and Québec using this same language of ‘ignorance and barbarism’ to justify its subjection of local populations and the agricultural exploitation of their land, insisting that colonial rule would ‘improve’ backward peoples and savage landscapes alike.37

How awareness of Britain’s dawning ascendancy shaped early visitors’ perceptions of the museum as a set of collections gathered from around the empire – and conversely how the museum shaped perceptions of the empire – is hard to say for sure. When it came to Ireland, for example, Powlett’s guide was suggestive rather than declaratory. He stated that the presence in the museum of stones taken from the Giant’s Causeway in Sloane’s native Ulster redounded ‘in honour of our own islands’ – an ambiguous phrase that appeared to submerge Ireland (or at least Ulster) in the larger idea of Britain. Unsurprisingly, the moral Powlett drew was one of Irish ignorance. He explained that ‘the common people of the country call them the Giants Causeway, from an old tradition that they were placed in that order by the ancient inhabitants of the island, who were of a gigantic stature,’ whereas in reality they were ‘entirely the work of nature’. More generally, Powlett used the museum’s collections to encourage nationalistic pride. The museum was, he said, ‘the largest and most curious … the world has to boast of’. ‘There is scarcely a country, though ever so distant,’ he pointed out, ‘that has not greatly contributed’ to its ‘almost infinite number of curiosities’. Its fish specimens had been ‘brought from various parts of the world’; its flintstones from ‘almost all parts of the world’; its ores ‘from almost all the known mines in the world’; and its drawings were ‘perhaps the finest that are to be seen in the world’. From its beginnings, the British Museum was framed as a showroom for celebrating the global reach of British power.38

The new museum also instituted several important changes in how the collections were handled and experienced. Sloane’s stipulation that his collections should not be mixed with others was observed: according to the British Museum Act, these were to be kept ‘whole and intire, and with proper marks of distinction’. But they now existed under the same roof with several other impressive libraries donated by aristocrats and even the king himself. Rehoused in a national institution and lacking Sloane’s animating presence, the collections inevitably came to lose something of their personal flavour, as did museum tours. Admission was no longer the expression of private favour but a matter of public application. Powlett still mentioned a certain delectable East Asian ‘soup nest’ but did not invite guests to lick it; such objects were not, after all, his personal property. There were fewer stories about individual curiosities and their pedigrees since these now lay buried in Sloane’s correspondence and catalogues, if not with Sloane himself in the family vault at Chelsea. All that remained of his interactions with Ayuba Suleiman Diallo and his dramatic odyssey in and out of slavery, for example, were a few short passages in his letters and the phrase ‘Interpr. Job’ in his Amulets Catalogue, all quite invisible to most museum goers. Powlett did describe a wasps’ nest from Pennsylvania but did not mention that it came from John Bartram, nor did he refer to Pennsylvania’s volatile milieu of colonization and war. Institutionalization separated objects from their contexts and depersonalized the collections. As Sloane’s curiosities became the nation’s, whom they came from became less important than what they were and where they fell in the order of things.39

Such order was in the eye of the beholder and subject to change. As Knight and Empson emphasized the Chain of Being to impress visitors with the hierarchies of the creation, Powlett alerted his readers to the Latin terms for many of the species he described. Yet to some, sorting the collections into discrete departments undermined the true purpose of a universal museum: to present a unified picture of the world. ‘Great as the collection is,’ Smollett had his fictional Squire Bramble grumble, ‘it would appear more striking if it was arranged in one spacious saloon, instead of being divided into different apartments, which it does not entirely fill.’ Sloane’s triumphant institutional legacy led to the new museum carving the collections into sections that could fit into the various apartments of Montagu House. The dream of total knowledge thus came into view and receded almost in the same instant, summoning a prospect of completeness it could not satisfy due to the exigencies of the physical space available and, Smollett implied, a limited public purse. ‘I could wish the series of medals was connected,’ Bramble went on regretfully, ‘and the whole of the animal, vegetable, and mineral kingdoms completed … at the public expence.’40

Admitting visitors free of charge who enjoyed no personal relationship to the collections was a highly significant innovation, although since tickets could be slow to materialize (they were required until 1805), knowing someone on the inside still helped. In 1782, Moritz managed to jump the two-week waiting list for tickets thanks to his connection to Karl Woide, a scholar who worked in the library. The logical corollary of admitting the public, who were presumed to lack knowledge of the collections, was the textualization of the museum experience. Written labels now appeared next to the objects on display and ‘concise and cheap’ guides like Powlett’s primed guests for tours. Powlett encouraged readers to study his guide prior to visiting and to keep it as a souvenir; and he recommended it to those who would never visit the museum at all: ‘it will likewise serve to give a tolerable idea of the contents to those who have no opportunity of seeing it.’ For the first time, general readers would be able to ‘see’ the collections through the medium of print. By 1778, readers might also view pictorial highlights without visiting thanks to the Rymsdyks’ Museum Britannicum. Sharing Horace Walpole’s vision of the artistic potential of the museum, the Rymsdyks encouraged artists to make their own sketches of items on show, proposing specific distances from which to do so and explaining that there were several ‘different ways of imitating an object’. Foreign guides were also published. Moritz brandished one in German by the London-based pastor Frederick Wendeborn, which ‘at least, enabled me to take a somewhat more particular notice of some of the principal things; such as the Egyptian mummy, an head of Homer, &c.’. Visiting the museum took its place in the polite culture of the middling as well as upper ranks of society.41

In some respects, Sloane’s published will and the British Museum Act constitute British equivalents of the American Declaration of Independence and Federal Constitution of 1787. They are written Enlightenment enunciations of universal egalitarian principles, albeit in the realm of culture and intellectual life rather than politics and government. In reality, what universal access meant in practice continued to evolve. Sloane’s 1753 will had stipulated that his collections be ‘visited and seen by all persons desirous of seeing and viewing the same … [and] rendered as useful as possible, as well towards satisfying the desire of the curious, as for the improvement, knowledge and information of all persons’. But the British Museum Act, published the following year, stated that the collections should ‘be kept for the use and benefit of the publick, with free access to view and peruse the same … under such restrictions as the Parliament shall think fit’; and that ‘a free access to the said general repository, and to the collections therein contained, shall be given to all studious and curious persons, at such times and in such manner, and under such regulations for inspecting and consulting the said collections, as [determined] by the said trustees’. The language of these two documents thus shows how the legal abstraction of creating a public museum with universal access, and the question of how to balance exhibition and display with scholarly research, became subject to oversight by those who hoped to ‘restrict’ and ‘regulate’ accessibility.42

In a notoriously partisan era, contemporaries nevertheless marvelled at the museum’s public status. ‘Considering the temper of the times, it is a wonder to see any institution whatsoever established for the benefit of the public,’ Smollett’s Bramble sighed. Remarkably, universal admission to view the collections was becoming a reality. ‘The company … was various, and some of all sorts … [including] the very lowest classes of the people,’ Moritz noted of the museum in 1782, ‘for, as it is the property of the nation, every one has the same right (I use the term of the country) to see it.’ This was a significant choice of words. Strictly speaking, neither Sloane’s will nor the British Museum Act spoke of the collections as national ‘property’ or of ‘rights’ of entry – but Moritz now used just these terms. Rights talk had erupted in Britain in the 1760s and 1770s during the explosive debates over the constitutional status of the American colonies, as they came to defend what they saw as their natural rights of life, liberty and property against arbitrary taxation. Radicals like John Wilkes, who advocated making Parliament more representative (and, tellingly, favoured enhanced funding for the British Museum), and the revolutionary Tom Paine, espoused full-fledged democracy, leading to the formation by 1780 of reformist organizations like the Society for Constitutional Information. Yet before the age of revolution, it was the creation of the British Museum back in the 1750s that first intensified political debate about who the public were and what their status was. Moritz’s invocation of ‘rights’ of entry demonstrates how revolutionary discourse then filtered back into the museum, reframing the question of access in explicitly political terms.43

‘The public spirit of the English is worthy of remark,’ observed François de la Rochefoucauld, the aristocrat and agricultural reformer who visited England to observe its industrialization in 1784. But access remained uneven. The status of women in the museum was markedly subordinate. Maids worked on the most menial rung of the staff, there were no female trustees and women were rarely admitted to the reading room for research. ‘I … flatter myself’, Powlett nonetheless gallantly offered, ‘that my readers among the ladies will be very numerous.’ Many ladies did indeed visit, though public excursions were fraught with issues of propriety. Caroline Powys visited in 1760 and returned in 1786 with her eleven-year-old daughter, recording her impressions in her diary. She noted collection highlights including several manuscript Bibles and the art of Maria Sibylla Merian, as well as ‘one room of curious things in spirits … but disagreeable’ (Gowin Knight had advised that pregnant women be sheltered from just such sights to prevent the alleged power of imagination from deforming their unborn children). ‘Sr Hans seems justly to have gain’d the title of a real virtuoso,’ Powys concluded. In partaking of the ‘spring diversions of London’ as an older woman in 1786, she took care to keep her daughter away from the fashionable pleasures of Ranelagh Gardens, guiding her instead back to the museum. Access to the museum’s own gardens, however, was restricted by trustee permission and roiled by class tensions. In 1769, one of the maids had endeavoured to stop a Mrs Ambrose Hankin from walking on the garden’s borders and picking a pear from a pear tree. ‘You are an impertinent slut to talk to me,’ Hankin fulminated, ‘for if you knew who you was talking to, you woud not talk in that manner … how dare you pretend to dictate to me.’44

Scholars battled the tourists, or so they felt. Empson griped in 1762 that his ‘constant & necessary attendance on the company that come to see the museum’ had ‘prevented him from making that progress he could wish’ in his work as a curator. As he reclassified Sloane’s plants according to Linnaean nomenclature in the 1760s, the naturalist Daniel Solander also protested at the disruptions caused by ‘companies’. Discussions about using the collections for scholarly purposes were in effect discussions about restricting access by class and gender, since ‘scholar’ was usually a synonym for gentleman. In 1759, Knight had stated that the overarching purpose of the museum was ‘to incourage & facilitate the studies & reserches of learned men’. In 1774, during a series of parliamentary hearings on the state of the museum, assistant librarian Matthew Maty offered his opinion that ‘the joining of companies is often disagreeable, from persons of different ranks and inclinations being admitted at the same time.’ That same year, an official blasted ‘persons of low education’ who ‘mixd’ themselves in with the educated merely to gratify their ‘idle curiosity’ and disrupt tours with ‘sense-less questions’. When the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots shook London in 1780, the spectre of mobocracy returned to menace the collections, at least in the minds of their managers. After damage had been done to the Bank of England and the Customs House, Parliament stationed 600 troops around the museum. The nation’s collections were now to be protected in the name of the public against the mob. When the French Revolution gave rise to the looting of aristocratic and church property, and prompted the transformation of the Louvre from a royal preserve into a republican institution in 1793, the British Museum decided to station guards on a permanent basis.45

The military conflict with France during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars created an atmosphere of deep hostility to republicanism and democracy in much of British society. Yet even before this point, the desire to restrict admission to the British Museum had prompted initiatives to introduce an entry fee, as early as 1774. But the logistics of admission had, in effect, narrowed access from the start. By the 1770s, entrance was allowed between nine in the morning and three in the afternoon, which excluded working people (admission did not include the summer months at this time). Where some recoiled at the idea of different classes mixing in the museum, the experience of access reinforced some visitors’ awareness of their low station rather than emboldening egalitarian feeling. Moving through the museum with his own German guidebook, Moritz attracted a crowd of fellow tourists, eager for information, only for one of the curators to express his ‘contempt’ at this challenge to his authority. William Hutton, founder of the first circulating library in the city of Birmingham, felt particularly uncomfortable on his visit in 1784. The process of writing to request tickets from the porter required that applicants mention their ‘condition’ for the approval of the librarian. This was a ‘mode [that] seemed totally to exclude me’, Hutton commented in his diary, and he ended up buying a ticket for nearly two shillings. Once inside, his group ‘began to move pretty fast’ so he asked a guide for clarification about what they were seeing, whereupon ‘a tall genteel young man in person … replied with some warmth, “What? would you have me tell you every thing in the museum?” ’ The docent brusquely referred him to the captions. ‘I was too much humbled by this reply to utter another word,’ Hutton confessed, and ‘no voice was heard but in whispers.’ In the public museum, all members of society were welcome but some were made to feel more welcome than others. Hutton took his leave, ‘disgusted’ at his treatment.46

Admission charges ultimately proved undesirable and unworkable. It was thought that they would lower the museum to the same moral status as commercial pleasure gardens like Ranelagh and Vauxhall while contradicting Sloane’s will and the British Museum Act. The drive to introduce them, however, does reveal a persistent pattern of hostility to the idea of equal access as a public ‘right’ on the part of a number of museum officials. One unnamed officer stated his view in an undated report around this time that the problem was that ‘persons of low education’ claimed ‘a right, which [the librarian] cannot controvert, to an equal participation of his attentions with those of the highest rank or the deepest erudition’. This ‘perfect equality in the rights of those who chuse to visit the museum’ had originated in ‘an opinion’ that because the museum had been ‘purchased with the money of the people’ they were ‘intitled to the free use of it’. Such an opinion, however, was ‘quite unfounded’. The use of the collections should instead be ‘placd in the custody of men of liberal education’ who would ‘diffuse’ knowledge in an appropriate manner.47

The museum’s public nevertheless expanded dramatically as the nineteenth century dawned, as did its collections. While Britain fought Napoleon on the battlefield and at sea, British collectors battled French rivals for the stunning treasures of antiquity then in the process of being uncovered. The early decades of the century witnessed the installation of truly spectacular new collections in Bloomsbury. These included the Rosetta Stone, which finally allowed for accurate translations of Egyptian hieroglyphics, and which the British Army took from the French in Ottoman Egypt in 1802; the many Greek and Roman sculptures given by the antiquarian and Grand Tourist Charles Townley in 1805; the Parthenon Marbles Lord Elgin cunningly removed from Athens between 1801 and 1812, before selling them on to the British government; the head of the Younger Memnon (Ramses II) brought from Luxor in 1818 by the erstwhile Italian circus man Giovanni Belzoni; and, a generation later, the Assyrian sculptures excavated and taken from Nimrud and Nineveh (ancient Mesopotamia, now Iraq) by Austen Henry Layard in the 1840s and 1850s. The number of people who saw the collections soared from 12,000 in 1805 to over 200,000 by the 1830s.48