Power, in the form of wealth, is the most important goal for a king—because it is the basis of social life.

—The Kāma Sūtra1

By performing sacrifices and offering gifts, one becomes a king in this world … By means of these rites and by performing sacrifices, O ruler, your enemies are destroyed and you will achieve kingship, without doubt.

—Kālikā Purāṇa (KP 85.79-80)

As a path of power, centered on the goddess as the embodiment of śakti in both its spiritual and material forms, Hindu Śākta Tantra has often been closely related to kingship and political rule in various periods of South Asian history. For śakti is not simply a spiritual or transcendent sort of metaphysical energy; it is also the material power that flows through the social body and the state as well as the physical body and the cosmos. As we saw in the previous chapter, Tantric texts promise the adept not just other-worldly benefits but also very this-worldly kinds of attainments, including the power to assume the throne and defeat enemy kings. Conversely, as Charles Orzech notes in his study of Chinese esoteric Buddhism, the tantras “were among the most important vehicles for the spread of Indian political and religious ideas throughout East, Central, and Southeast Asia.”2 Indeed, the king is, in many ways, the “Tantric actor par excellence,”3 the ideal embodiment of the Śākta as seeker of power and the male consort of the land represented by the goddess. As Flood observes, “The transgressive violence and eroticism of Tantric deities became tapped and controlled by the institution of kingship.”4

Perhaps nowhere is this connection between Tantra and kingship more apparent than in the case of Assam, where the worship of the goddess Kāmākhyā was closely tied to political power, from the mythical demon-king Naraka down to the last of the Ahom kings before British colonial rule. As the embodiment of divine desire and power, Kāmākhyā formed a key religio-political center during several of Assam’s ancient and medieval dynasties, such as the Pālas, Kochs, and Ahoms. Yet at the same time, Kāmākhyā was also a central point of interaction between the various indigenous communities of the northeast and the brāhmanic forms of Hinduism coming from Bengal and central India. This complex interaction between Tantra and kingship is apparent as early as the Kālikā Purāṇa, which not only narrates the conquest of Assam by king Naraka but also devotes its last several chapters to the seemingly secular matters of statecraft, politics, and military strategy.5 Clearly written for a king, the Kālikā Purāṇa combines elements of Vedic ritual, non-Hindu tribal practices, left-hand Tantra, and the rules of statecraft.

Similarly, the second most important Tantric text composed in Assam—the Yoginī Tantra, from the sixteenth or the seventeenth century—also provides a mytho-historical narrative of medieval Assam, recounting the divine origins of the Koch king Viśva Siṅgha and the violent struggles for power between the Kochs, Ahoms, and Mughals that took place in the sixteenth century.6 The inner wall of the present temple still bears an inscription dedicated to Viśva’s sons, Naranārāyaṇa and Chilarai, who rebuilt the complex in the sixteenth century and were praised as generous patrons of the goddess.

However, one of the most important and recurring themes throughout the Assamese literature is the profound ambivalence of kingship. For while he is the embodiment of worldly power and strength, the king is also—like the goddess Śakti herself—tied to the inevitable realities of violence, bloodshed, and impurity. In the particular case of Assam, moreover, the king is consistently linked to powerful but also impure traditions such as indigenous religions, non-Vedic rituals, and the deeply ambivalent power of sacrifice. From the time of the Kālikā Purāṇa down to the nineteenth century, in fact, the institution of kingship was closely linked to the offering of human sacrifice, a practice that probably shows the influence of several indigenous tribes of the northeast.7 Again, this reflects the unique power of Tantra, as a tradition that appropriates, harnesses, and transforms the dangerous but life-giving forces at the margins of the social body.

Kingship in Assam is at once a reflection of wider South Asian ideals of kingship and a unique instantiation of those ideals in the specific case of northeast India, with its complex history of negotiations between Hindu and non-Hindu indigenous traditions. On the one hand, since the time of the Varman dynasty (fourth to seventh centuries), the kings of Kāmarūpa have largely fit the model of the ideal king described in the Epics and Purāṇas. Throughout the Purāṇas, the king is praised as at once powerful, divine, and yet potentially dangerous, a being “endowed with divine luster … As he controls the people, he is Vaivasvata (the son of Vivasvān, the sun). As he burns evil, he is Agni, the fire-god; and as he gives gifts to brāhmaṇs, he is Kubera, the god of wealth”; and yet, “if he is sinful … rains stop in his kingdom.”8

Particularly in the Śākta or goddess-centered traditions, the king is also imagined as the male counterpart to the goddess as nature, earth or the land. As Thomas Coburn notes, the interplay between the goddess and the king may well be “one of the important continuities in Indian religion” and a key to the “growth of the cult of a buffalo-killing Goddess from local to pan-Indian scope between the ninth and sixteenth centuries.”9 As the embodiment of the earth, land, and nature, the goddess is the ultimate symbol of the kingdom that is wedded to and gives power to her human consort, the king: “The goddess, she who slays the buffalo demon and who gives victory to the king, is therefore that very Nature in which men have their place and from which they await the satisfaction of their needs.”10 Thus the Śākta and Tantric traditions continue many themes from earlier Vedic and Purāṇic models of kingship, such as the ideal of the king as supreme sacrificer; but they also add the ideal of the king as Tantric hero who can harness the tremendous energy of the goddess as the embodiment of divine power. As Flood suggests, the medieval period in India saw the rise of a more “aggressive, power-hungry” concept of lordship, which sought to appropriate the erotic violence of the goddess in the person of the king: “The king is also the patron of ritual, who assumes the classical Vedic role of the patron of the sacrifice … But the new Tantric conception of kingship saw the king as a deity warrior whose power is derived from the violent erotic warrior goddesses … The power of the king was linked to the power of the Goddess.”11

Not surprisingly, Tantric worship became increasingly popular in royal and aristocratic circles throughout India during the early medieval period, from the Chandella kings of Khajuraho, to the Kalacuris of Tripurī, and the Somavaṃśis of Orissa.12 The worship of the quintessentially Tantric goddesses, the yoginīs, also owed much to royal patronage in these same regions. Various tantras promise that a king who worships the yoginīs will see his “fame reach to the four oceans,” making him “king of all kings” (rājendraḥ sarvarājānām): “such worship will enable the king to achieve success in his military campaigns and to ward off invasion from neighboring kingdoms.”13

Something we see in several Tantric regions is the complex tension and negotiation between non-Hindu tribal kingship and mainstream brāhmaṇic traditions. The worship of powerful Tantric goddesses is often a complex point of intersection between indigenous kings and the priests who would convert them and win their patronage. A classic example is the case of the Chandellas. An originally non-Hindu tribe of the Gond ethnicity, the Chandellas carved out a kingdom in central India in the ninth century and gradually adopted brāhmaṇic traditions. Today they are perhaps most famous for building the spectacular erotic temples at Khajuraho and for establishing one of the most important early Tantric temples of the 64 yoginīs.14

This dynamic between tribal kings and the patronage of Tantric deities is perhaps nowhere more apparent than in Assam. Throughout the northeast region, non-Aryan ruling families were progressively brought within the brāhmaṇic fold and given a divine ancestry going back to Hindu deities. This began with oldest known historical dynasty of Kāmarūpa, the Varmans (fourth to seventh centuries), who are believed to have been non-Hindu people but traced their origins to the mythical king Naraka, the ambivalent divine-demonic son of Viṣṇu. Likewise, the second major dynasty, the Śālastambha (seventh to ninth centuries) is explicitly referred to as a mleccha or non-Hindu, tribal, barbarian dynasty; yet it too would claim to be descended from the dynasty of Naraka.15 Virtually all later indigenous kings of the northeast claimed some similar divine descent once they began to patronize brāhmaṇic traditions. Thus the Manipuris linked their kings to Arjuna, the Koch kings traced their origin to Śiva; the Chutiyas began worshipping Hindu deities and traced their origin to Indra; and the Ahoms not only traced their lineage to Indra but also identified their own deities with Hindu gods and goddesses, such as Chao-pha for Indra, Khan-Khampha-pha for Devī or Śakti, etc.16

However, Śākta Tantra appears to have reached its peak under the kings of Assam’s Pāla dynasty (tenth to twelfth centuries). As we saw in Chapter 1, it was under the Pālas that the Kālikā Purāṇa was composed and Assam’s sculpture and architecture reached their pinnacle. The great Pāla kings, Ratnapāla, Indrapāla, and Dharmapāla, clearly fit the model of the divine ruler who is at once the patron of sacrifices and also the Śiva-like consort of the goddess/kingdom. Indeed, many Assamese scholars believe that Indrapāla and others in his line were public patrons of orthodox rites and private patrons of the tantras: “what appears to be most likely is that the Kāmarūpa kings received Tantric dīkṣa [initiation] only in their private life while in public they remained followers of Brahmanical faiths.”17 Throughout the copper plate grants that survive from ancient Assam, the Pāla kings are identified as Parameśvara, the Supreme Lord, meaning both Śiva and the king; they are equal to Kāma in sexual prowess; they are supreme patrons of sacrifices; and, above all, they are indomitable in battle. For “war was the sport of kings, and success in war and valour in battle was the rulers’ highest ambition.”18 Thus King Ratnapāla (ca. 920–60) is described as a descendent of the demon-king Naraka, but he is also a destroyer of demons and so wears a garland made of the heads of “kings defeated in battle”19:

Even being the Parameśvara, he is the promoter of joy in Kāmarūpa. Even belonging to the family of Naraka he causes the pleasure of the enemy of Naraka [Viṣṇu] … Even being a vīra [warrior] he moves like an intoxicated elephant. His beauty surpasses even that of Cupid … His valor is productive of the conquest of the whole world. … He is an Arjuna in fame, a Bhīmasena in the battlefield, the god Yama in anger, a forest fire in respect of the grasses in the form of enemies.20

Ratnapāla’s son Indrapāla (ca. 960–90) is widely believed to have been a patron of Śākta Tantra, and it seems that the worship of the goddess (Mahāgaurī or Kāmākhyā) and her consort (Śiva or Kāmeśvara) was popular in kingdom during his reign. The king himself is said to have been “learned in pada (grammar), vākya (rherotic), tarka (logic) and tantra.”21 And Indrapāla is praised in no less spectacular terms as both a supreme lover, “to the damsels like Kāmadeva,” and a supreme warrior, omnipotent in battle: “He vanquished the enemy by dint of his might, which was increased with the three śaktis,” namely, the three royal powers of prabhuśakti or power of the king, mantraśakti or power of good counsel, and utsāhaśakti or power of energy.22

The greatest of the Pāla kings was Dharmapāla (ca. 1035–60), during whose reign the Kālikā Purāṇa was likely composed. Like his predecessors, Dharmapāla is celebrated as a “vanquisher of enemies” and a consort of the goddess in war: “On the battlefield beautiful with flower-like pearls struck off from the heads of elephants killed by the blows of his sword, king Dharmapāla alone remained victorious to sport with the goddess of wealth born of battle.”23

Even after the collapse of the Pāla dynasty and the fragmentation of the early Kāmarūpa kingdom, this association of kingship with the goddess, with bloodshed, and with terrible power would continue in the medieval dynasties of Assam. As we will see below, the Koch kings Viśva Siṅgha and Naranārāyaṇa Siṅgha resurrected the worship of the goddess in the sixteenth century, as did the Ahom kings Rudra Siṅgha and Śiva Siṅgha in the eighteenth century. Both the Kochs and Ahoms were, again, non-Hindu tribal kings who adopted brāhmaṇic traditions and patronized a kind of hybrid goddess worship woven of both indigenous and mainstream Hindu traditions.

Both Hindu mythology and the historical narratives of Assam closely link kingship with the goddess—though in complex and ambivalent ways, for the king is consistently portrayed as both a devotee of the goddess and a man flawed by sin and weakness. Like the goddess herself, the king is inevitably tied to the realm of bloodshed and the impurity that comes with it. As early as the Laws of Manu and the Mahābhārata, the king was conceived as a deeply ambivalent character who wields a dangerous and frightening power. This is what Heesterman calls the “conundrum of the king’s authority,” or the “ambivalent numinosity” of the king, who is seen as terribly powerful in both a positive and a negative sense. On the one hand, the king protects the people, maintaining the order of the universe; indeed, he is dharma incarnate. But on the other hand, the king is “roundly abominated. That he is simply the ‘eater of the people’ who devours everything he can lay hands on is already a cliché in the Vedic prose texts … [T]he king is put on a par with a butcher who keeps a hundred thousand slaughterhouses.”24

Likewise, the Kālikā Purāṇa consistently portrays the king as a being of dangerous power whose strength and self-will always threaten to bring his own downfall: “The power of kings is like the heat of the sun. If there is pride in it, he should abandon it like a diseased body”; indeed, “the self-will of kings will always destroy them. The self-willed prince surely goes astray.”25 Above all, the king is inevitably tied to impurity because of his involvement in punishing criminals, offering blood sacrifice, and waging war: “Kings immediately become impure when passing judgment, when consecrating an image, when performing sacrifice, or when invading an enemy kingdom.”26 That is why the king needs to support his brāhmaṇs, who alone can purify him of the evil deeds that he must inevitably perform. As Heesterman notes, “The king … desperately needs the Brahmin to sanction his power by linking it to the Brahmin’s authority. The greater the king’s power, the more he needs the Brahmin.”27

In part, this complex relationship between kings and brāhmaṇs in Assam reflects a larger tension between power and purity in South Asian Hindu traditions as a whole. Since the earliest Vedas, the brāhmaṇ was associated with purity and goodness (sattva) and the king with power and strength (rajas, vīrya, ojas); and the sacrificial ritual, as Romila Thapar suggests, served as a key exchange of material and symbolic capital between the pure priest and the powerful king: “The brāhmaṇa had a relationship with the kṣatriya embodying political power. The sacrificial ritual was an exchange in which … the priests were the recipients of gifts and fees and the kṣatriya was the recipient of … status and legitimacy.”28 But at the same time, in the Assamese tradition, we also see a deep tension between brāhmaṇic Hinduism and the local indigenous traditions of the northeast that were slowly being brought into the Hindu fold. Again, this clearly reflects the real political history of the region, since most of Assam’s kings came from tribal backgrounds and brought with them a variety of indigenous rituals and deities that were never fully “Hinduized.” And it is reflected throughout the narratives of Assam’s great mythic and historical kings.

As we saw in Chapter 1, the first devotee of the goddess was king Naraka, who is said to have founded the first kingdom in Assam, then known as Prāgjyotiṣapura. An ambivalent character from the very beginning, Naraka was born the son of Lord Viṣṇu in his boar incarnation, who united with the goddess Earth during the highly inauspicious time of her menstrual period. Indeed, it was precisely because he was conceived during Earth’s menstruation that this son of a god was doomed to become demonic: “Because [he was born] in the womb of a menstruating woman by the seed of the boar, although the son of a god, he became a demon.”29 From his origins, however, Naraka was also associated with the sacrificial ritual and was in fact born upon the sacrificial ground of King Janaka.30 Thus he was from his birth an impure but dangerously powerful being.

According to the Kālikā Purāṇa, Naraka conquered the indigenous peoples of the region, slew Ghaṭaka, the king of the kirātas, and established brāhmaṇic traditions in the realm. His father Viṣṇu gave him a special weapon called none other than śakti, made him ruler of Kāmarūpa, and instructed him to worship Kāmākhyā on the great mountain Nīlakūṭa.31 The kingdom flourished until the arrogant Naraka forged an alliance with Bāṇa, a demon king in the non-Hindu tribal region of Sonitpura in eastern Assam. Thereafter, he became “inimical to gods and Brahmans … He destroyed heaven and earth, carrying his torture and destruction everywhere.”32 Thus he was cursed by the sage Vasiṣṭha that so long as he lived, the goddess would remain hidden. In fact, the goddess does seem to have gone into hiding for some time, as there is no clear mention of Kāmākhyā or her temple between the time of the Kālikā Purāṇa (tenth to eleventh centuries) and the rebuilding of the present temple (sixteenth century).33

Another popular story about a demon king and the goddess is told about both Naraka and the tribal ruler of Sonitpur, Bāṇa. In the latter version of the legend, the arrogant king Bāṇa wished to see the goddess. She told him she would reveal herself to him only on the condition that he could build a stairway up the hill to the temple in one single night before the first cock’s crow in the morning. The king worked all night with his men, building the staircase almost to the top, and then, just before he laid the last stone, the goddess miraculously caused the cock to crow. Thus “the Goddess got a stairway to her temple without having to show herself to the ashura king.”34 Much the same story is also told of Naraka, except in this case the demon-king wants not just a vision of the goddess, but the goddess herself as his bride. Again, the goddess in this narrative magically causes the cock to crow just before the king can finish his task, rebuking him for his demonic arrogance: “Hey proud demon, your request has been denied.”35

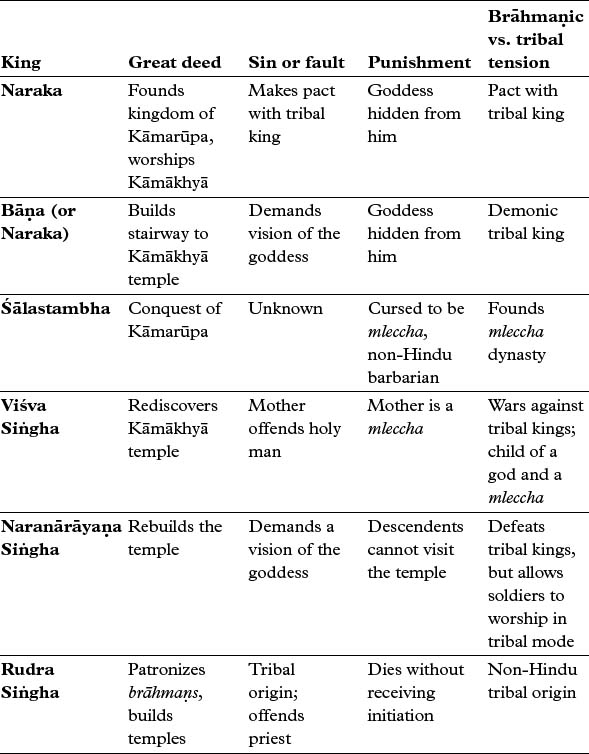

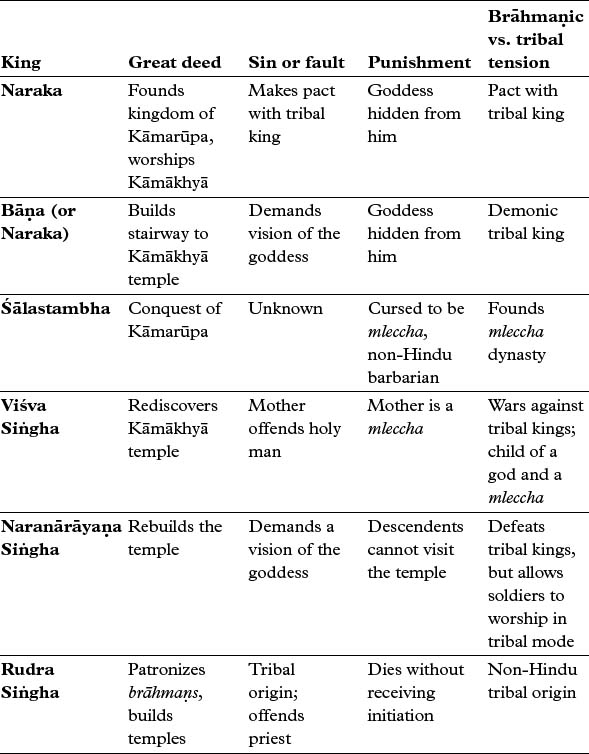

In sum, each of these narratives links the pride of the king—and specifically the pride of a king who either is himself non-Hindu or else who makes deals with a tribal king. And in each case, the king is punished by being denied access to the goddess. Ironically, however, the demon king was to have a long legacy in Assam, as virtually all the later kings of ancient Kāmarūpa, from the Varman dynasty (fourth to seventh centuries) to the Pāla dynasty (tenth to twelfth centuries) traced their lineage to Naraka. Perhaps the most mysterious and little-understood of the early Kāmarūpa dynasties was the Śālastambha kingdom, which flourished from the seventh to ninth centuries. According to two copper plate inscriptions from the ninth and eleventh centuries, the Śālastambhas claimed to be descended from the demon king Naraka. But, like Naraka, they too suffered some unknown curse (the portion of the plate that presumably explains why the dynasty became mleccha is damaged and unreadable) and were doomed to be called mlecchas, that is, non-Hindu barbarians. King Śālastambha himself became “lord of the mlecchas.”36

According to a widespread series of legends and semi-historical narratives, the temple of Kāmākhyā was rediscovered and her worship reinstituted in the sixteenth century by Viśva Siṅgha (1515–40) of the Koch kingdom immediately adjacent to Kāmarūpa (modern Cooch Behar). Apparently, the original temple had been destroyed by some natural disaster or invasion and was not rebuilt until Viśva and his sons conquered the region.37 Again, Viśva Siṅgha embodies the tensions between Hindu and tribal traditions and the dangerous power of kingship. As Subhajyoti Ray suggests in his study of northern Bangla and Assam, the Koch kingdom is yet another example of the “gradual process of ‘Hinduisation” of a tribal group that progressively replaces indigenous practices with mainstream Hindu traditions. Like many other northeast tribes, the Kochs did so by claiming a divine lineage descending from the gods.38 But it is a complex and ambivalent lineage, also linked to sin, curses, and their non-Hindu tribal past.

The Yoginī Tantra, for example, provides a mytho-historical narrative for the birth of king Viśva, which, again, involves the themes of Hindu–tribal tensions and the legacy of a curse. Here we learn that Viśva was the son of a beautiful, powerful, and wise yoginī name Revatī, who lived “in the land of Koch, adjacent to the yoni cave. She was honored as a beautiful yoginī, but she assumed the body of a mleccha.”39 Both charming and wise, versed in both the Vedas and Āgamas, the yoginī engaged in joyful love-play with Lord Śiva himself. But when a powerful sage came to her seeking alms, she ignored him, and the sage therefore cursed her to become a mleccha, that is, a non-Aryan, outcaste, or barbarian. The child born of her love-play with Śiva was Vinu Siṅgha (a.k.a. Viśva Siṅgha), who conquered the Saumaras (Ahoms) and the other tribes of the region and established a mighty lineage of Kuvācā (Koch) kings. As Lord Śiva praised the king and his descendents,

His many sons were great kings of the earth. The Kuvācās were all righteous kings and fierce in battle … Just like my son, Bhṛṇgarīṭa, Vinu is my offspring. So too, at the end of the age, Vinu will achieve supreme perfection. The descendents of that family are all kings and dwell on Mount Kailāsa.40

Indeed, because Viśva took birth in Kāmākhyā out of his own desire (svasya kāmasya), so too, all his descendents were destined to be kāmapālakās, meaning both “kings of Kāmarūpa” and “kings of desire.”41

Viśva’s rediscovery of Kāmākhyā temple is a popular and often repeated narrative (even making its way into modern popular film42). According to one widespread narrative, the king was leading his armies into Assam to wage war against the tribal kingdoms of the region, when he lost his way in the forest. There he came upon an old woman who gave him water from a sacred spring. The spring, she said, flowed from the goddess’ own yoni and marked the spot at which the original Kāmākhyā temple stood. The king prayed to the goddess, offered the sacrifice of a pig and a cock, and vowed that, if she would aid him in battle, he would build her a new temple made of gold. The king was indeed victorious and established a new kingdom in Assam with Kāmākhyā at its religio-political center.43 However, like Naraka before him, Viśva represents a complex negotiation between non-Hindu indigenous cultures and Hindu traditions imported from central India. Indeed, the new Kāmākhyā temple was established directly amidst and on top of existing tribal ritual practices. According to historical accounts from Cooch Behar, Viśva “built this temple over a mound where the inhabitants of the nearby Nilachal hill used to sacrifice pigs, fowls and other animals and … imported numerous brahmans from Kanauj and Benaras and other centres of learning to run it.”44 Here we see a classic example of the complex negotiation between indigenous and brāhmaṇic traditions in Assam: the tribal king claims a mythical descent from Śiva and then transforms the goddess’ temple from a site of tribal sacrifice into a center of brāhmaṇic rites.

A similar set of narratives, with a similar tension between brāhmaṇic and tribal traditions, surrounds Viśva’s son, Naranārāyaṇa Siṅgha (1540–86). It was Naranārāyaṇa and his brother Chilarai who brought most of the region under a single rule, subduing the Ahoms, Manipuris, Kacharis, Jaintias, and Tripuris.45 In 1565, they rebuilt Kāmākhyā temple, whose inner wall still contains an inscription celebrating their glory as supreme heroes and devotees of the goddess:

Glory to the king Malladeva [Naranārāyaṇa] who, by virtue of his mercy, is kind to the people, who in archery is like Arjuna, and in charity like Dadhichi and Karṇa; he is like an ocean of all goodness, and he is versed in many Śāstras; his character is excellent; in beauty he is as bright as Kandarpa, he is a worshipper of Kāmākhyā. His younger brother Śukladeva [Chilarai] built this temple of bright stones on the Nīla hill, for the worship of the goddess Durgā in 1487 Śaka [1565 CE]. His beloved brother Śukladhvaja again, with universal fame, the crown of the greatest heroes, who, like the fabulous Kalpataru, gave all that was devoutly asked of him, the chief of all devotees of the goddess, constructed this beautiful temple with heaps of stones on the Nīla hill in 1487 Śaka.46

Like Naraka, Naranārāyaṇa also had a complex relationship with the indigenous peoples of Assam. Although he was famed for his conquest of many indigenous kings, Naranārāyaṇa was also known for his tolerance of indigenous traditions. According to one well-known story, on the eve of battle with the Ahoms, Naranārāyaṇa allowed his Kachari soldiers to worship Śiva in their own indigenous mode, alongside his brāhmaṇic method of pūjā:

Besides the Vedic rites there were and even now are various tribal modes of worship of Shiva. On the eve of his expedition against the Ahoms, as recorded in the Darang Rajvasmsavali, King Naranarayana of Koch-Bihar worshipped Shiva according to accepted sastric rites. But at the insistence of his Kachari soldiers, the sacrifice of swine, buffalo, he-goats, pigeons, ducks and cocks and offering of rice and liquor and also dancing of women (deodhai) were allowed. By edict he allowed this form of Siva worship in the north bank of the Brahmaputra river.47

Like Naraka, however, Naranārāyaṇa was also a flawed king, whose pride eventually led to a terrible curse. According to one widespread story, a pious brāhmaṇ named Kendukalai received a vision of the goddess. Upon hearing of this vision, Naranārāyaṇa also wished to see Kāmākhyā and demanded that the priest help him pray until the goddess revealed herself. The goddess, however, became so furious at his audacity that she beheaded the priest and cursed the king: thenceforth, if he or any of his descendents ever visited the temple they would be doomed.48

This intimate connection between kingship and the goddess continued even after the defeat of the Koch Behar kings by the Ahoms in the seventeenth century. Although originally a non-Hindu people derived from the Tai or Shan race, who first entered Assam in the thirteenth century, the Ahoms adopted many brāhmaṇic traditions and worship of Kāmākhyā after they conquered the region.49 The Ahoms brought in new priests from Bengal and other parts of India and constructed hundreds of temples throughout the region. As part of their complex blending of Hindu and indigenous traditions, they not only identified Ahom gods with Hindu deities, as we saw above, but also gave both a traditional Ahom and a Sanskritic Hindu title to each of their kings, who thus embodied fusion of Ahom and brāhmaṇic traditions.50

The greatest of the Ahom kings was Rudra Siṅgha (Siu-Khrung-Pha, 1696–1714), who ruled during the zenith of Ahom power, subjugated the neighboring Jaintia and Dimasa kingdoms, and raised a vast army against the Mughal empire. According to one widespread narrative, Rudra decided that he should adopt brāhmaṇic rites and worship of the goddess, thus being initiated into the “cult of strength or Śakti.”51 Too proud to receive initiation from any of his subjects, however, he invited a famous Śākta priest named Kṛṣṇarāma Bhaṭṭācārya to come to Assam from Bengal, promising him the care of Kāmākhyā temple itself. Even then, the king had second thoughts and changed his mind, sending the priest away. But then the king received a cataclysmic warning that he took to be a sign from the gods that he had offended them:

After the priest departed there was a severe earthquake that shattered several temples. Rudra Singh thought he had attracted divine displeasure by hurting a favorite of God and recalled the Mahant and satisfied him by ordering his sons … to accept him as their Guru.52

Kṛṣṇarāma was subsequently given management of Kāmākhyā temple by Rudra’s son, Śiva Siṅgha (1714–44), perhaps the greatest patron of Śāktism among the Ahoms. Kṛṣṇarāma’s descendents, in turn, became known as the Parvatīya Gosāiṅs, whose method of worshipping Kāmākhyā is said to have continued down to the present era.53 Ironically, however, many contemporary Assamese historians also blame Śiva Siṅgha for the eventual decay and “final crash” of Ahom rule, largely because of his over-indulgence in Tantra and “absorption in the Śākta cult”:

Shiva Singha used to spend most of his time in Shakta worship … The Ahoms in their fanatic zeal for their new religion had turned indifferent to the political consequences of their actions. The Ahoms now became unmindful of the effects of their religious conduct on the stability of the government … Such patronage now became the criterion of excellence of kings and individuals rather than … state service.54

Thus, in each of these narratives, we can see a consistent structural theme that centers around kingship, the goddess, and a basic tension between Hindu and tribal religious practice. In each case—Naraka, Bāṇa, Viśva Siṅgha, Naranārāyaṇa Siṅgha, and Rudra Siṅgha—the king worships the goddess and conquers his enemies; but in each case, the king also has some flaw that prevents him from seeing the goddess or worshipping her properly; and in each case, this flaw centers on the king’s relation to indigenous traditions, whether by making alliances with tribal kings, allowing tribal practices to continue, or by his own non-Hindu origins.

In sum, the king in these narratives is always an ambivalent character, a devotee of the goddess, but also a flawed being tied to impurity, sin, and non-Hindu indigenous traditions.

There are good reasons for this connection between the political power of the king and the spiritual power of the goddess—and also for the ambivalent status of the king. As Coburn notes, the goddess and the king mirror one another in many ways, sharing a “common character as both valorous and irascible.”55 The goddess is, after all, the embodiment of the earth and the land, of which the king is the ruler and protector. The goddess, moreover, embodies a fierce and awesome source of power, the power to destroy demons, to cleanse the world of evil, and, by extension, to defeat one’s enemies and rival kings. As Biardeau notes, “she is closer to earthly values … but she is more apt to make use of the violence without which the earth could not live.”56 But more important, the king also embodies many of the same tensions as the goddess. Above all, he reflects the tension between dangerous impurity and terrible power, between the polluting flow of blood and the strength to destroy enemies. Like the goddess, the king is bound to the world of warfare, battle, violence, and inevitable impurity that is necessary to the functioning of the state.

These three related themes of kingship, impurity, and the brāhmaṇic–tribal tension all come together in the ritual of sacrifice, of which the king is the supreme patron. Virtually all of the inscriptions and textual evidence from Assam, from ancient Kāmarūpa down to the Ahom era, consistently link the king with the bloodshed of sacrifice and war. Thus the earliest copper plate inscriptions from the Varman dynasty portray the Varman kings as patrons of the great royal rite, the horse sacrifice, which was performed as a prelude to the conquest of new regions. Indeed, Mahendravarman was praised as the “repository of all sacrifices” (yajñavidhīnāmāspadam)57 and his mother as “the goddess of sacrifice”58 (yajñadevī), because of their generous patronage, as were their descendents: “Mahendravaman is said to have performed two horse sacrifices, Bhūtivarman one and Sthilavarman two sacrifices. This sacrifice was always preceded by some conquests.”59

This link between kingship and sacrifice is also seen throughout the copper plate grants of Assam’s Pāla kings (tenth to twelfth centuries), who are endlessly praised as patrons of sacrifice. Thus Ratnapāla (920–60) “caused the whole world to be crowded with white-washed temples of Śiva, the dwellings of brāhmaṇs to be stuffed with various types of wealth, the places of sacrifice to be littered with sacrificial posts, the sky to be filled with sacrificial smoke.”60 Likewise, Harṣa Pāla (1015–35) is praised as making offerings of enemy blood, spilled on all sides in the great sacrifice of battle: “In the battlefields he, by breaking with weapons the foreheads of the enemy elephants, repeatedly made offerings of drinks to the demons on all sides, who being thirsty drank up hurriedly the lukewarm blood mixed up with a profuse quantity of froth.”61

Probably composed during the reign of the Pāla kings of the tenth and eleventh centuries, the Kālikā Purāṇa makes the most explicit link between kingship, sacrifice, and dangerous power. Throughout the text, blood sacrifice is identified with both the attainment of political power and the conquest of enemies in battle: “By sacrifices one attains liberation. By sacrifices one attains heaven. By offering sacrifice a king always conquers enemy kings.”62 Indeed, a large portion of the Kālikā is devoted to the complex details of kingship, statecraft, politics, and military strategy. Like the classic Hindu political text, the ArthaŚāstra, the Kālikā Purāṇa provides detailed directions on economic affairs, agriculture, forts, farms, taxes, and especially warfare. For “kings should always be engaged in war. If one concludes he can obtain land, wealth, or allies, there should be wars.”63 At the same time, the text emphasizes that the king must also be a good patron of brāhmaṇs, carefully listening to their teachings and funding their ritual performances.64 Here we see, again, that the Śākta traditions of Assam are the result of a complex negotiation between the Sanskrit-trained priests who composed these texts and the local kings whose patronage they sought.

Following the ancient Indian social model, which dates back to the early Vedas, the Kālikā Purāṇa imagines the kingdom as an alloform of the human body. In the well-known myth of the Ṛg Veda mentioned above, the entire universe is born from the sacrifice and dismemberment of the primordial person, Puruṣa, who is ritually divided up into the various forms of both cosmic and social hierarchies. Puruṣa’s body forms of the paradigm for the cosmic hierarchy of heaven, atmosphere, and earth as well as for the hierarchy of the social classes: brāhmaṇs become the head, the kṣatriyas become the torso, the vaiśyas become the legs, and the śūdras become the feet of the body politic. Similarly, the ideal kingdom is conceived on the analogy of a human corpus with its even limbs: “The king, the ministers, the kingdom, friends, the treasury, the army, and the citadel—these seven are known as the limbs of the kingdom [rājyāṅgam].”65 As B.K. Sarkar comments, “This conception is not merely structural or anatomical but also physiological … It embodies an attempt to classify political phenomena in their logical entirety.”66

Just as the proper maintenance of the Vedic universe was said to depend on the regular performance of rituals, so too the proper order of the sociopolitical universe relies on the king’s generous patronage of sacrifice. And just as the Vedic sacrifice was believed to regenerate and reunify the cosmic body of the first sacrificial victim, Puruṣa, so too, the sacrifice performed by the king is necessary of the ongoing unity and vitality of the body politic. Indeed, he would risk disaster and ruin if the sacrifice were not performed:

Having performed these [rites], his army, kingdom and treasury increase, but if these sacrifices are not performed, famine, death, etc will occur … 67

By performing sacrifices and offering gifts, one becomes a king in this world. Therefore to have a kingdom one should follow dharma. By means of these rites and by performing sacrifices, O ruler, your enemies are destroyed and you will achieve kingship, without doubt. The [enemy] king does not follow the dharma of a king or perform aśvamedha sacrifices, etc, therefore you should perform all these, O best one!68

Many of the rites described in the Kālikā Purāṇa are specifically designed to ensure the prosperity of the kingdom and the conquest of enemies. During the autumnal worship of Durgā, for example, the king should prepare a horse sacrifice that will “increase his strength” and determine his success in war.69 In other rites, the king should fashion an earthen image of his enemy and magically infuse it with the enemy’s spirit. Finally, he should “pierce its heart with a trident and sever its head with a sword,” before marching against his enemies on horseback.70

Above all, the power of blood sacrifice can be harnessed by the king and turned directly against his enemies in battle. Whereas the Vedic sacrifice had, on the offering of a pure victim, identified with the divine offering of Puruṣa, the Śākta sacrifice centers on an impure, demonic victim—ideally, a buffalo—identified with the evil and danger of a hostile king. And the deity worshipped here is not a pure male god, but rather the goddess in her most terrible, blood-thirsty, left-hand forms as the destroyer of evil:

A king may offer sacrifice for his enemies. He should first consecrate the sword with the mantra, and then consecrate the buffalo or goat with the name of the enemy. He should bind the animal with a cord around his mouth, reciting the mantra three times. He should sever the head and offer it with great effort to the goddess. Whenever enemies become strong, more sacrifices should be offered. At such times, he should sever the head and offer it for the destruction of his enemies. He should infuse the soul of the enemy into the animal. With the slaughter of this [animal], the lives of his unfortunate enemies are also slain. “O Caṇḍikā, of terrible form, devour my enemy, so and so”—this mantra should be repeated. …. “This hateful enemy of mine is himself in the form of the animal. Destroy him, Mahāmārī, devour him, devour him, spheṇg spheṇg!” With this mantra, a flower should be placed on his head. He should then offer the blood, with the two-syllable [mantra].71

Here we see that the ritual explicitly manipulates the transgressive forces of impurity, bloodshed, and the severed head in order to unleash the violent power of the goddess in her most terrible Tantric form, now turned against an enemy in battle.

This link between kingship, power, and sacrifice (especially buffalo sacrifice) persisted long after the time of the Kālikā Purāṇa and the end of the Pāla dynasty. Even as late as 1781 when the Ahom king Gaurīnatha Siṅgha (Chāophā Shuhitpungngam Mung) assumed the throne, the coronation culminated with the royal sacrifice of a buffalo: “For seven days and nights, drums were beaten, gongs were struck, and flutes were blown … At the time of ascending the throne, the king pierced to the death a buffalo. All the great men of he country were entertained with feasts for seven days.”72 Up to the end of Ahom rule, sacrifice remained closely tied to royal power, believed to be “conducive to the welfare of the kings and their people,” and “performed for bringing victory to Ahom arms or in celebration of victories in war.”73

In fact, the link between Kāmākhyā, kingship, and sacrifice has even survived into the twenty-first century. During the Ambuvācī celebration in 2002, King Gyanendra and Queen Komal of Nepal visited the temple with the intention of offering animal sacrifice. However, the plan drew such protest from animal rights groups that the king himself offered the substitute of vegetarian offerings and left the site before a buffalo, a sheep, a duck, and a goat were sacrificed on his behalf.74

According to Assamese texts like the Kālikā Purāṇa and Yoginī Tantra, the supreme sacrifice that can be offered by a king is that of a human being. Indeed, human sacrifice receives a great deal of attention in the Kālikā Purāṇa, where it is said to be the most perfect offering and greatest source of power: “With a human sacrifice, performed according to ritual precepts, the goddess is pleased for a full one thousand years, and with three humans, for 100,000 years. With human flesh, Kāmākhyā and Bhairavī, who assumes my form, are pleased for three thousand years.”75 The Yoginī Tantra likewise declares that the sacrifice of a human boy (narasya kumāra) is the highest of all sacrifices, worth more than the offering of any number of yaks, tortoises, rabbits, boars, buffaloes, rhinos, or lizards.76 As Wendell Beane points out, human sacrifice had deep roots in the political history of Assam, closely tied to power, warfare, and royalty: “The sacrificial cults had royal patronage, and sacrifices were demanded of the most loyal officials … [T]he occasion tended to coincide with calamities such as war or for obtaining wealth.”77

But did human sacrifice ever really take place? It is tempting, of course, to dismiss accounts of human sacrifice as mere mythological fantasy or British colonial paranoia (which in some cases they were, as we will see in Chapter 6). However, there seems to be sufficient evidence from textual and ethnographic that suggests that human sacrifice did indeed occur among several indigenous communities of the northeast and was carried over into Śākta Tantra.

The practice of human sacrifice, I would argue, is another example of the rich intermingling of traditional Vedic rites with indigenous practices of the northeast hills. Human sacrifice is clearly mentioned in the Vedas and Brāhmaṇas, and the human being is even listed as the first among animals fit for sacrifice. Yet paradoxically, consumption of human flesh is explicitly considered taboo throughout the same literature.78 As Heesterman suggests, the sacrifice of a human being is part of the same basic conflict at the heart of the sacrifice—the problem of violence and impurity at the center of a ritual that is supposed to be life-giving and pure. As we saw in Chapter 2, human sacrifice, like animal sacrifice in general, was gradually eliminated in mainstream Hindu traditions, as the sacrifice was increasingly domesticated and the violent elements were gradually replaced by a logical system of ritual procedures.79

Yet human sacrifices continued throughout many non-Vedic indigenous traditions, particularly in remote, mountainous regions like Assam. Several of the northeast tribes, such as the Nagas and Garos, were head-hunters with a long tradition of collecting human heads. And human sacrifice was widely practiced by many other northeast tribes such as the Jaintias, Khasis, and Chutiyas.80 As Briggs points out, the rite of human sacrifice described in the Kālikā Purāṇa has little in common with any Vedic ritual, but quite a lot in common with non-Hindu indigenous practices: “though they may be performed by non-Aryans under Brahmanic auspices, they form no part of the Aryan religion. But they are recommended to princes and ministers … The ritual bears little resemblance to Vedic sacrifices, and the essence of the ceremony is the presentation to the goddess of the victim’s severed head.”81 Again, the rite of human sacrifice described in texts like the Kālikā Purāṇa and Yoginī Tantra is likely the result of a complex interaction between Vedic and indigenous traditions, through which Vedic paradigms that were later rejected by the mainstream tradition were reworked within a more accommodating religious framework.

The Kālikā Purāṇa makes it clear that human sacrifice is at once an extremely powerful and yet also dangerous and potentially polluting act. In fact, a brāhmaṇ cannot offer a human victim without losing his priestly status.82 Members of the kṣatriya class may offer human sacrifice, but only with the permission of the king, who alone can sanction such a rite. Above all, in times of political turmoil such as anarchy or war, it is the king alone who may perform the puruṣamedha:

The prince, the minister, the counselor, and the sauptika, etc., may offer human sacrifice [in order to attain] kingship, prosperity and wealth. If one offers a human being without the permission of the king, he will find great misfortune. During an invasion or war, one may offer a human being at will, but only a royal person [may do so], and no one else.83

The preferred human victims, moreover, are said to be neither a priest nor an untouchable, but ideally “the mercenaries of enemy lands, who are captured in battle.”84

Overall, this ritual is surrounded with an aura of fear and danger. It must be performed in the cremation ground.85 As the locus of human remnants and the ashen leftovers of bodies, the cremation ground is a place of utmost impurity in the Hindu religious imagination and is the dwelling place of Śiva in his terrible form as Bhairava.

The human victim, however, is described in terms that draw explicitly on the classical ritual of the Vedas. Indeed, the victim is a representation of the primordial sacrificial victim, Puruṣa, who was slain and dismembered to create the various parts of the cosmos at the beginning of time. In the consecration of the victim, all the gods and aspects of the cosmos are ritually identified with various parts of the body, infusing the sacrifice with the powers of the universe and, in a sense, reconstructing the original cosmic victim. Thus, one should worship Brahmā in the cavity of the skull, the earth in the nostrils, the sky in the ears, water on the tongue, Viṣṇu in the mouth, the moon on the forehead, and Indra on the check, declaring, “O, most auspicious one, you are the supreme embodiment of all the gods!”86 Still more important, the king also identifies himself with victim, who is offered in his place in order to insure the protection of his kingdom and wealth:

Save me, taking refuge in you, together with my sons, livestock and kinsmen. Save me, together with my kingdom, ministers and fourfold army, giving up your own life, for death is inevitable … Do not let the demons, ghosts, goblins, serpents, kings, and other enemies attack me, because of you. Dying, with blood flowing from the arteries of your neck and smearing your limbs, cherish yourself, for death is inevitable…

The one worshipped in this way has my own form and is the seat of the guardians of the four quarters. He is possessed by Brahmā and all the other gods. Even though he was a sinner, the man worshipped in this way becomes free of sin. The blood of this pure being quickly becomes nectar. And the great goddess, who is the mother of the universe and also herself the universe, is pleased.87

What we have here, then, is a complex series of homologies that symbolically link the body of the victim, first, with the body of the cosmic or the cosmic man, Puruṣa; second, with the body politic of the kingdom; and finally, with the body of the king himself. And just as in the Vedic sacrifice, the universe is reintegrated through the performance of the ritual and the reconstruction of the cosmic man, so too, in this sacrifice, the kingdom and the body politic are rejuvenated and preserved through the offering of this now-divinized victim. As in the case of other Tantric sacrifices, the focal point of the human sacrifice is the ambivalent but powerful offering of the severed head. Indeed, the sacrificer must carefully observe exactly how and where the severed head falls, for the Kālikā Purāṇa provides a long list of various good and bad omens associated with its direction, the sound that it emits, and how the blood flows out, along with their portents for the future of the kingdom.88 Ultimately, by standing in all-night vigil holding the severed head as the supreme gift to the goddess, the king achieves the highest fruit of the sacrifice:

If the adept stays awake all night holding the head of a human being in his right hand and the vessel of blood in his left, he becomes a king in this life, and after death, he reaches my [Śiva’s] realm and becomes lord of hosts.89

Here again we see the circulation of divine power between the goddess and her devotee, flowing through the physical medium of blood.

Much of the efficacy of rituals like human sacrifice, I would argue, lies precisely in the use of impurity and the dangerous power that such transgressive acts unleash. As we have seen above, the king himself is a complex figure, often associated with impurity, bloodshed, and death. Forced by his dharma to deal with the impurity of war, conquest, and punishment, the king is likened to an “eater” of the people and a “butcher.”90

For the early brāhmaṇic tradition, priestly ritual serves as the expiation for the inevitable impurity that comes with the office of the king: “The guilt of the warrior or the evil of the sacrificer was easily removed by the priest in Vedic times.”91 As Heesterman argues, however, the brāhmaṇic tradition would gradually seek to eliminate as much impurity and violence from the ritual as possible—ultimately even excluding the impure king from the sacrificial arena: “The elimination of conflict… resulted in the internal contradiction of Vedic ritualism. This has already come out in the fact that the kṣatriya—the king who… is the ideal sacrificer—is… excluded from the agnihotra … The kṣatriya perpetrates many impure acts, he kills and plunders.”92

For the later Śākta Tantric, however, the sacrifice seems to function quite differently. Indeed, the Tantric sacrifice actually seizes on and exploits the transgressive nature of ritual violence, precisely in order to unleash its dangerous power. Tantric ritual turns to the dark and furious energy of the goddess in her most terrifying forms—as Kālī, Cāmuṇḍā, and Caṇḍikā—to let loose their violent power. As Biardeau suggests, the goddess in her aggressive, militant forms is the supreme symbol of a kind of necessary violence: she is the one who deals in bloodshed, battle, and impurity in order to preserve the cosmic order:

When we pass from bhakti to Śāktism … she becomes the preeminent divinity, the Śakti who is superior to Śiva, and this reversal of the hierarchy is accompanied … by a reversal of dharma: what was prohibited becomes permitted, the impure becomes pure. She is closer to earthly values … but she is also more apt to make use of the violence without which the earth could not live.93

We might also say that the goddess represents the violence without which the kingdom and the political order could not be maintained.

The Tantric traditions, however, make no attempt to rationalize this violent impurity, but instead seek to transform it into a tremendous source of power. The one who knows how to harness this violent power can become a master of this world, a hero in statecraft and war. The Kālikā Purāṇa makes this abundantly clear, often making an explicit appeal to the desires of the royal classes: “He who performs this [sacrifice] enjoys all the pleasures of this world and after death remains in the abode of the goddess for the three ages and then becomes a sovereign king on earth.”94 Ultimately, the king who performs these rites will achieve success in everything—not only “all the objects of his wishes and Śiva’s form in the afterlife” but also supreme success in battle and virtual invincibility against any foe: “he has the power to subdue gods, kings, women and others … He lives a long life, becomes prosperous, endowed with wealth and grain; he becomes … invincible to enemies.”95 Ultimately, “that hero, like me [Śiva] enters into battles. The weapons of the enemies become like grass upon a fire … The Tiger among men becomes strong and virile.”96

Human sacrifice appears to have continued throughout the northeast region long after the period of the Kālikā Purāṇa and the Pāla kings, persisting up to the arrival of the British empire. As late as the nineteenth century, the Jaintia kings offered human victims to the goddess Durgā at her mountain temple near Nartiang, Meghalaya. Still today, one can see the ritual mask allegedly worn by human victims and the sacrificial hole into which the heads were offered, sending them down to the river far below the temple (Fig. 17).97 As we will see in Chapter 6, the practice apparently continued up until the 1830s when the British authorities put a stop to it after four British subjects were kidnapped and taken to be offered to the goddess.98

The Ahoms, too, are said to have performed several human sacrifices, particularly during their war with the invading Muslims in the early seventeenth century. On the eve of the great Saraighat battle, the Ahom commanders and soldiers were said to have knelt at Kāmākhyā temple, praying to the goddess: “’O mother Kāmākhyā, eat up the Moghuls and give us victory.’ This no doubt put courage and confidence in the hearts of the Assamese army.”99 According to the Ahom burañjīs, the defeated Muslim commanders were subsequently sacrificed, beheaded, in some cases flayed, and offered to Kāmākhyā by the Ahom kings:

Near the principal shrine of Kamakhya is the smaller temple of Bhairavi … here human sacrifices were once held. In 1615 Karmachand, son of Satrijita, a commander of an invading Musalman army, was sacrificed to the goddess Kamakhya.100

In 1616 King Pratap Siṅgha (Chāopā Shushengphā) is even said to have made a garland of severed heads from the Muslims slain in the sacrifice of battle—an act that is clearly a tribute to the goddess in her terrible forms as Kālī and Cāmuṇḍā, with her own dripping garland of severed heads:

The king came back to the capital and offered oblations to the dead and sacrifices to the gods. In the month of Dinshi (Phalgun) the heavenly king made a “Mundamala” (garland of heads) with the heads of the deceased Musalmans.101

However, the most infamous example of human sacrifice in medieval Assam is the worship of the terrible goddess Kecāi Khātī, “the eater of raw human flesh,” by the Chutiya kings of eastern Assam.102 Annual sacrifices of human victims—usually criminals sentenced to capital punishment—were apparently offered at the Tāmreśvārī temple near the town of Sadiya. Details of the offerings are found both in various British colonial accounts and in manuscripts such as the Tikha Kalpa, which was found in the Manipur State Library. According to this text, “Human sacrifices are made, after the royal consent has been obtained, on the occasion of public calamities such as war or for the purpose of obtaining great wealth.”103 As the sacrificer offered the victim, he was to pray as follows: “O Goddess, living on the golden mountain, I offer this sacrifice to thee! He is good and stout and without blemish, I bind him to a post. I offer this sacrifice to remove my misfortune.”104 Again, the central act was the beheading of the victim, whose severed head was then added to a heap of skulls that were “piled in view of the shrine.”105

With the coming of British colonial rule and the end of royal power in the northeast, the practice of human sacrifice largely died out by the early nineteenth century. However, there are in fact still periodic rumors of the rite being practiced secretly around Kāmākhyā, and the region retains its aura of blood rites and dangerous but tremendous supernatural power to this day. As recently as 2003, in fact, a man was arrested for attempting to sacrifice his daughter during the Ambuvācī celebrations in the hopes that the goddess “would bestow him with tremendous powers.”106

In sum, the Śākta traditions of Assam represent a striking example of the complex relations between kingship, sacrifice, impurity, and power that characterize the Tantric traditions of South Asia as a whole. They reveal the intimate associations between the king as the embodiment of the male deity (Śiva, Kāma, Kāmeśvara) and the goddess as the land and divine power (Śakti, Kāmākhyā, Kāmeśvarī). The two are joined symbolically and ritually through the circulation of śakti, which is embodied above all in the circulation of blood—namely, the blood that flows from animal (and human) victims, and the blood that flows from enemies slain in the sacrifice of battle.

However, the Assamese traditions also highlight another key aspect of this circulation of power and blood: namely, the impurity of power, the association of the king with the dangerous pollution that comes with sacrifice and war. Throughout the narratives of kingship from Assam, from the Kālikā Purāṇa to the Yoginī Tantra, from mythic king Naraka down to Rudra Siṅgha, the king is repeatedly associated with impurity and bloodshed. Finally, the Assamese traditions also highlight the complex tension between indigenous, non-Hindu traditions and the brāhmaṇic Sanskritic traditions that lies at the heart of Śakta Tantra in this region. Indeed, the long history of Tantra in the northeast could be described, in part, as a complex negotiation between the Assam’s many non-Hindu kings and the brāhmaṇs they patronized. Again, this is also a complex tension between purity and power.

As we will see in the following chapter, much the same logic of sacrifice, the circulation of blood, and the inherent impurity of power also lies at the heart of the esoteric sexual rites that constitute the most poorly understood aspect of Tantric practice.