濟 按 採 挒 肘 靠. 此 八 卦 也.

濟 按 採 挒 肘 靠. 此 八 卦 也.The Text with Commentary

With every movement, the entire body must be light and nimble, and all of its parts must be kept strung together like a string of pearls.

一 舉 動. 周 身 俱 要 輕 靈. 尤 須 貫 串.

Yi ju dong. Zhou shen ju yao qing ling. You xu guan chuan.

This first verse of the treatise is the most crucial and important for correct Taijiquan practice. The three aspects of being light, nimble, and stringing all the parts together of every movement are the essential skills needed for genuine performance of Taijiquan. Actually, the remaining verses of this treatise are in many ways the more technical aspects of how to develop these three optimum functions of body movement.

When these three attributes of lightness, nimbleness, and stringing the parts of every movement together are accomplished, Taijiquan for the most part is mastered. This verse is explaining that with every motion of the body, not just the motions of the arms, feet, or waist, but in unison with the four limbs, torso, and head as well—all must function as one complete unit and be moved with lightness and nimbleness so that everything and every part of the body feels “strung together like a string of pearls.” In other words, move one pearl and all the other pearls move with it. Move one body part and all the other body parts must move as well.

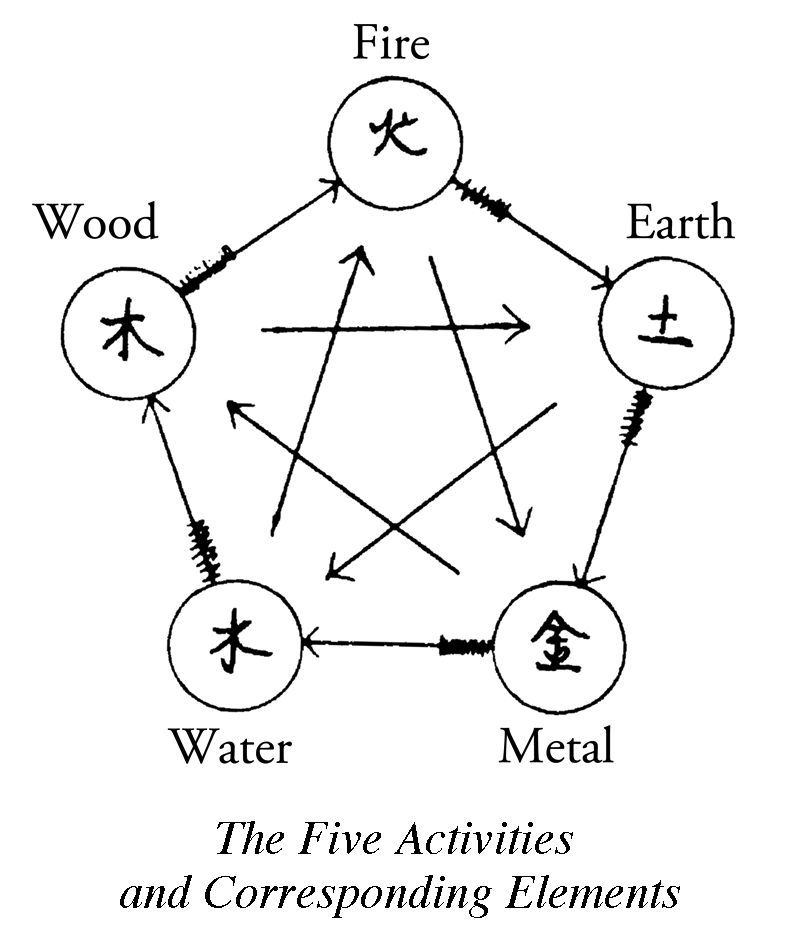

In Taijiquan, the word “movement” (動, dong) needs some clarification, as movements within Taijiquan are regulated according to the functions and movements of the Eight Operations and the Five Activities. Hence, the idea here of stringing all the parts together within the movements ensures that the entire body moves as one complete unit and in accordance with the principles of the Eight Operations and Five Activities.

The function of lightness within the practice of Taijiquan originates in the principle of “Suspending the head from above as if by a thread” or sometimes rendered as “Retain a light and sensitive energy on top of the head.” In either case, the idea is, through imagination, to sense the top of your head as if it were being pulled slightly upward by an imaginary thread. However, the area that is sensed is not directly on top of the head, rather the area of the soft spot we had as infants. This area is a little back from the actual topmost point of the head. The reason for sensing here is because when we imagine this spot being pulled upward, the chin will drop to a level position and the back of the neck will straighten slightly. Thus, the head will be in perfect alignment. In contradistinction, if you were to suspend from the actual top of the head, the chin would raise and the head tilt backward somewhat, causing the head to be out of alignment.

To be light doesn’t mean raising your body upward so that all the energy is in your upper body like a ballet dancer. Lightness has several definitions, depending on which part of the body is being discussed. For example, lightness in the feet and legs doesn’t mean no weight is placed on them (which would be impossible), rather that the body’s weight is concentrated into the bottoms of the feet with an awareness and sensitivity.

A statement from the Book of Changes (易 經, Yi Jing) best describes this sensitivity in the feet, when it says: “The fox walks cautiously over thin ice.” Rather than focusing on the idea of being cautious and careful here, which the Yi Jing is recommending in this analogy—consider the way a fox literally walks on thin ice.

When a fox walks across a frozen lake or river, before committing its entire body weight into a leg, it first lightly places one forward paw on the ice, using a slight energy to make sure it is safe first and strong enough to support its weight. If the ice proves safe, the fox will place its weight down—if not, it withdraws the paw. This is the idea of being sensitive, alert, and light.

Likewise, in performing Taijiquan, specifically in stepping forward, the heel lightly touches the ground first (sensing if it is safe). Then the foot is rolled flat, allowing the body’s weight to shift and sink into the Bubbling Well (湧 泉, Yong Quan) point on the bottom of the stepping foot.

If Taijiquan adherents do not step in this manner, like a fox walking on thin ice, they are just blindly—and often, clumsily—setting down the feet without any awareness or sensitivity. This is like two hard objects connecting together but are easily separated—like two pieces of wood or bricks that lose contact when slid against each other.

In contradistinction, stepping with sensitivity and awareness, as in setting down the heel and rolling the foot flat, is like how a wet mop attaches and adheres to a floor. Try kicking a wet mop to separate it from the floor, and it won’t easily slide away—nor lose its attachment to the floor. More likely your foot will just be entrapped by the strands of the mop.

Lightness, within Taijiquan, refers primarily to Intrinsic Energy (勁, Jin), the energy developed in the sinews and tendons through relaxed, sensitive, and alert use of employing the entire body as one unit. It is because of this lightness that when a Taijiquan master pushes, the opponent feels very little actual pushing strength coming from the master’s hand. This is a result of the master’s hands being sensitive, alert, and light, and not using any external muscular force.

To help illustrate this idea better, perform this simple exercise with two people. Person A extends her arm up and out at chest height with the palm facing upward. Person B stands to the side, placing his hands directly under A’s wrist and elbow, supporting her arm. B then asks A to completely relax her entire arm, shoulder, elbow, and wrist so that the entire arm just rests on B’s palms and is devoid of any energy. At this point, B is entirely holding up A’s arm. Then, when B removes his palms, the result will be A’s arm falling down immediately to her side. This exercise shows an example of collapsing, not relaxing, and is certainly not the way of Taijiquan.

Repeat the procedure with B supporting A’s arm, but this time B tells A to put just enough energy into her arm to hold it in place and then removes his hands. Usually, A’s arm will either bounce upward slightly or down slightly. Without telling A the correct response, practice the exercise until nothing happens, meaning A’s arm remains in place when B removes his hands. No movement happens here, because A has learned to apply just the right amount of energy to keep her arm in place, while remaining as light and relaxed as possible.

When a Taijiquan adherent can attach to an opponent with lightness and sensitivity, but not collapse when the opponent moves or attempts to get away, this person has developed an important aspect of intrinsic energy and is exemplifying the idea of lightness in the arms.

Two other aspects are of great importance in regards to acquiring lightness: learning how to rid the legs of all tension, and increasing the marrow in the bones.

Ridding the legs of all tension means learning how to relax the muscles in the thighs and calves. Normally, whenever we place the weight into a leg, the muscles tighten and cling to the bone. Just like when we make a fist to punch, the normal process is to wrap the muscles tightly around the bones of the hand and arm. This is what the Taijiquan principle admonishes against doing, when it says, “Do not use external muscular force.”

Concerning the legs, there must be a constant awareness of the tension created from every movement, and if there is a conscious effort to constantly let go of that tension, the legs will gradually become more and more relaxed over time—and lightness in the legs will be achieved. This is not easy to do, but it must be practiced and developed so that the intrinsic energy can pass through the legs and into the waist.

The third aspect of lightness involves the idea of increasing the marrow in the bones. An infant, for example, has soft and pliable bones because the marrow content is very high. In practicing Taijiquan, the qi and breath become hot. This heat creates increased blood circulation, and this increased blood circulation causes more blood and qi to spread throughout the body. In Daoist thought, all this new blood, qi, and heat begin to penetrate into the muscles and sinews of the body that surround the bones. Gradually, the qi and heat from the muscles then penetrate into the bones, creating more marrow. The more marrow, the greater the pliability and lightness acquired.

The function of nimbleness in Taijiquan practice does not necessarily mean quickness, but rather the ability to move effortlessly with agility as the situation requires. The true source of nimbleness comes from the spirit (神, shen). A cat is a great example of embodying nimbleness, not only because it can jump ten times its own height from its ability to apply lightness and nimbleness, but also because it does so in accordance with its spirit.

Observe the eyes of a cat the moment it is about to move and you will clearly see its spirit. Just as when a cat sees a mouse, it first concentrates its spirit, sinks into its rear legs, and waits with sensitivity and alertness. When the mouse makes its move to escape, the cat springs off its rear legs and intercepts the mouse using lightness and nimbleness.

To be nimble in Taijiquan means to move effortlessly with all the parts of the body loose and relaxed, yet sensitive and alert, and distinguishing clearly the substantial and insubstantial aspects of your body, so you move with complete centeredness and grace throughout. When stepping, turning, or moving about in Taijiquan, it should feel as though your feet and legs are gliding across the floor, not like a laborious movement. In Sensing Hands practice, nimbleness gives you the skill to be able to interpret your opponent’s every move, just like a cat catching a mouse.

The opposite of nimbleness is clumsiness and awkwardness concerning physical movement, and being dull and dimwitted regarding mental functions. In Taijiquan, you need to be nimble in movement and nimble in mind. In English, the definition of nimble is to be quick and agile, but in the Chinese language the term for nimble is ling (靈) and it has a much broader meaning, such as “lively spirit,” “quick witted,” “mysterious,” and “an active reflex.” The Chinese take it even further, as Daoists associate ling with immortals and being spiritual, as immortals are capable of physical flight, obviously the apex of lightness and nimbleness skills.

The function of “stringing all the parts together like a string of pearls” in Taijiquan practice is accomplished in three principle manners, or relationships, found within the concept of the Six Unions (六 合, Liu He). 1

The Six Unions refer to a set of principles of movement, with the first three sets called “The Three Relationships.” These three relationships relate to certain body parts and movement:

The first relationship is a unified movement of the hips and shoulders. Meaning, that when, for example, the right hip is to be turned, the right shoulder will follow in unison, as if the two were connected and so move synchronously with one another.

The second relationship is a unified movement of the knees and elbows. For example, if the bent rear leg is to be raised by slightly unbending the knee, then the corresponding elbow will unbend at precisely the same rate.

The third relationship is a unified movement of the feet and hands. For example, like a marionette, when the feet are moved the hands follow accordingly.

This brief summary of the Three Relationships provides some insight as to how all the body parts connect and move in unison.

The idea of movement “being strung together” is often translated with the inclusion of an implied meaning of “like a string of pearls.” No matter how much a person twists or moves it, a string of pearls remains strung together, and if one pearl is moved, then all the pearls move.

Hence, when moving in Taijiquan, all the body parts (pearls) move as though all the joints of the body were threaded together like a string of pearls.

Another function and meaning of stringing all the parts together must be understood from the words, “In every movement.” As stated earlier, there is a difference between the “movement” mentioned in this verse, as it is referring to an entire Taijiquan posture, while “parts” is talking about the gestures that make up the posture. It is the gestures within a posture that are connected like a string of pearls, not the postures themselves.

The idea that all the postures are connected without the slightest pause is probably the most frequently misinterpreted principle of Taijiquan practice. In fact, the postures are connected by using the analogy of a broken lotus root. The fibers remain intact and connected, yet there is a noticeable separation and distinction between parts in the root. Although the root is one piece, each break separates it into parts. Just as the postures within the Taijiquan form have clear breaks between them, they connect together—like a lotus root—to make a complete form. But, the gestures within each posture connect and flow like the movements of pearls on a string.

In performing Taijiquan, many postures and gestures are performed to complete an entire solo form. Each posture is distinct, with the beginning and end of each posture clearly distinguished in the mind. Otherwise, the posture movements will overlap, extend, or fall short, causing the practitioner’s mind-intention to be confused and unfocused. For example, when moving through the gestures (parts) of the Taijquan posture Rolling-Back and into the gestures of Pressing, there must be a clear distinction of where Rolling-Back ends and Pressing begins. The pause between postures, so to speak, may be minute and slight, but it is clear enough so that the spirit (shen) clearly distinguishes and senses it.

A way of understanding how this is applied in Taijiquan is to define all the postures and gestures into beats and half-beats (or da beats). Each gesture, or posture count, then has two parts, a beat and a half beat. For example, Pushing is defined by four beats—counted as one da, two da, three da, and four da. On each beat and each half beat the body is moved into certain positions, but on the last da, or half-beat, of the fourth posture count, there will be a slight pause so the practitioner doesn’t overextend or contract the movement. Anyone watching would not necessarily perceive the pause, but within the mind-intention of the practitioner, this pause is clearly sensed and distinguished.

Whether talking about the gestures of a posture by “stringing all the parts together” or clearly distinguishing each posture from each other with the analogy of a broken lotus root, all movements in Taijquan must accord with certain principles.

Although there are twenty-two traditional, foundational principles of movement in Taijiquan, the first ten are discussed in detail to focus on the aspects that apply to moving the body as one unit.

The Foundational Principles of Tai Ji Quan (太 極 拳 基 本 要 點, Tai Ji Quan Ji Ben Yao Dian) was first presented in Chen Kung’s Chinese book Tai Ji Quan, Sword, Saber, Staff, and Dispersing Hands Combined. This list consolidates the theories of principles for the correct practice of Taijiquan. Chen Kung derived the list of these principles from the Yang family transcripts and they have become a standard reference for all Taijiquan forms. Master Liang always stressed teaching principles as the essence and heart of Taijiquan practice. Someone may learn the movements correctly from a teacher, but without the mastery of the underlying principles, the full skills and benefits of Taijiquan practice can never be accomplished. All practitioners of Taijiquan should deeply study and apply these principles to their practice so they can master the art of Taijiquan in its fullest sense.

1) Retain a light and sensitive energy on top of the head. 一) 虛 領 頂 勁; Yi) Xu ling ding jin.

2) Express the spirit in the eyes to concentrate the gaze. 二) 眼 神 注 視; Er) Yan shen zhu shi.

3) Hollow the chest and raise the back. 三) 含 胸 拔 背; San) Han Xiong Ba Bei.

4) Sink the shoulders and suspend the elbows. 四) 沈 肩 垂 肘; Si) Chen jian chui zhou.

5) Seat the wrist and straighten the fingers. 五) 坐 腕 伸 指; Wu) Zuo Wan Shen Zhi.

6) Keep the entire body centered and upright. 六) 身 體 中 正; Liu) Shen ti zhong zheng.

7) Draw in the tailbone. 七) 尾 闾 收 住; Qi) Wei Lu shou zhu.

8) Relax the waist and relax the thighs. 八) 鬆 腰 鬆 胯; Ba) Song yao song kua.

9) The knees appear relaxed, but not so relaxed. 九) 膝 部 如 鬆 無 鬆; Jiu) Xi bu ru song wu song.

10) Adhere the soles of the feet to the ground. 十) 足 掌 貼 地; Shi) Zu zhang tie di.

11) Clearly distinguish the insubstantial and substantial. 十 一) 分 清 虛 實; Shi yi) Fen qing xu shi.

12) Upper and lower should mutually follow each other, and the body should move as one unit. 十 二) 上 下 相 隨. 週 身 一 致; Shi er) Shang xia xiang sui. Zhou shen yi zhi.

13) The internal and external should be mutually joined together with natural breathing. 十 三) 內 外 相 合. 呼 吸 自 然; Shi san) Nei wai xiang he. Hu xi zi ran.

14) Use the mind-intent, do not use muscular force. 十 四) 用 意 不 用 力; Shi si) Yong yi bu yong li.

15) The qi should circulate freely throughout the body, yet dividing the upper and lower activity. 十 五) 氣 遍 週 身. 分 行 上 下; Shi wu) Qi bian zhou shen. Fen xing shang xia.

16) Mutually connect the mind-intent and qi. 十 六) 意 氣 相 連; Shi liu) Yi qi xiang lian.

17) Move in accordance with the gestures of the posture. Do not bend forward and do not expose your back. 十 七) 式 式 势 順. 不 拗 不 背. 週 身 舒 適; Shi qi) Shi shi shi shun. Bu ao bu bei. Zhou shen shu shi.

18) All the gestures are to be uniform, continuous, and unbroken. 十 八) 式 式 均 勻. 綿 綿 不 斷; Shi ba) Shi shi jun yun. Mian mian bu duan.

19) In performing the postures, be free of excess and deficiency, and seek to be centered and upright. 十 九) 姿 势 無 過 或 不 及. 當 求 其 中 正; Shi jiu) Zi shi wu guo huo bu ji. Dang qiu ji zong zheng.

20) Use the method of concealing by not outwardly exposing. 二 十) 用 法 含 而 不 露; Er shi) Yong fa han er bu lu.

21) Seek tranquility within movement; seek movement within tranquility. 二 十 一) 動 中 求 靜. 靜 中 求 動; Er shi yi) Dong zhong qiu jing. Jing zhong qiu dong.

22) Lightness brings about nimbleness, nimbleness results in movement, and movement results in transformation. 二 十 二) 輕 則 靈. 靈 則 動. 動 則 變; Er shi er) Qing ze ling. Ling ze dong. Dong ze bian.

Think of the first ten Tai Ji Quan Principles of Movement as a beginner’s guide to applying Taijiquan, and the full twenty-two as more for those who are well acquainted with Taijiquan practice and principles. When these first ten principles are all applied within each posture and gesture of Taijiquan, all the parts will be strung together so that the entire body can move as one unit.

1. Suspend the head as if by a thread means to imagine a light and sensitive energy on top of the head, or to imagine a thread is suspending the head from above. This both stimulates the spirit and keeps the head in perfect alignment.

2. Concentrate the line of vision means to move the head and waist in perfect unison as if the eyes were in the waist. This also keeps the spirit focused and keeps the whole body moving as one unit.

3. Sink the shoulders, suspend the elbows, seat the wrists, and relax the fingers. Sinking the shoulders means to let them drop naturally, not forcing them down. This is to help keep the breath and qi from rising into the upper body. Suspending the elbows means to imagine they are held in a position to better enable blood circulation and so not to let them collapse into the body. Seating the wrists is to imagine as if the hands and wrists were resting on a pillow, so that the wrists and hands are in perfect alignment. This will create the perfect conditions for blood and qi to flow freely into the hands. Relaxing the fingers means to keep each finger slightly bent, not straight and not curled, so the blood and qi can enter the fingertips. This entire third principle is primarily employed to allow blood and qi to flow through the entire arm and into the fingertips, as well as to create the conditions for intrinsic energy (jin) to be expressed out through the arms and hands.

4. Hollow the chest and raise the back aids in the development of adhering qi to the spine (raising the back) and sinking the qi into the Dan Tian (hollowing the chest). But it also helps in keeping the back rounded out and sinking the shoulders so that there is no pinching of the shoulder blades together.

5. Abide by the lower Dan Tian has two important functions: First, it keeps all the movements generating and functioning from the waist. Second, it keeps the mind-intention on sinking the qi into the Dan Tian.

6. Draw in the Wei Lu (tail bone) keeps the spine aligned and prevents leaning. Drawing in means to tuck the tailbone in and down about one inch so there is no protrusion of the buttocks.

7. Relax the waist and thighs means not to collapse the hips inward nor expand them outward, but to keep them in perfect alignment with the thighs. Relaxing the coccyx opens the perineum area so that blood and qi can flow into it freely and unobstructed.

8. Do not let the knees pass over the toes does not mean the knees can be aligned directly with the toes. It means that the calf and shin of the front leg is held upright and perpendicular to the floor, so that if looking down the toes can still be seen—as the knee isn’t passing over or hiding them. This principle prevents overextension of the legs and from creating too much stress and tension upon the knees and legs.

9. Round out the legs and knees is crucial for ridding the legs of tension, for opening up the perineum area, and for developing root (central equilibrium). In all related Asian inner-cultivation methods, be it meditation, yoga, martial art, Taijquan, and so forth, there is this principle of opening the legs so as to allow blood and qi to enter into the perineum area.

10. Sink the weight into the Bubbling Well points on the bottom of the feet is really a misnomer. Actually, it is impossible to place the entire weight of the body into specific qi centers, especially the Bubbling Well points, as they are located behind the balls of the feet in the hollow area near the center of each foot. Therefore, this principle can’t be taken literally. The idea here is that if a person focuses on the Bubbling Well point when committing weight into a given leg, the entire foot can be relaxed and the weight will evenly distribute throughout the foot. Otherwise, there will be a tendency to press down the foot (causing the root to be easily severed from the tension) or more weight gets placed onto the heel of the foot or into the toes (again causing easy severing of the root).

Applying these ten Tai Ji Quan Principles of Movement can be seen, in analogy, as if a person were floating in mid air—from the head being suspended upward and the feet sunk downward—so that the entire body can function freely without hindrance, while the waist controls and generates all function of movement from the middle of the body.

Calmly stimulate the qi, so the spirit is retained internally.

氣 宜 鼓 盪. 神 宜 內 斂.

Qi yi gu dang. Shen yi nei lian.

Moving water cannot be boiled is the underlying message of “calmly stimulate the qi.” The qi is like an inherent oxygen within the blood deriving its power in the same manner as steam coming off boiling water.

Actually, the very ideogram for qi in the Chinese shows a pot with rice inside being cooked, with the vapors rising and symbolizing the energy of qi. In the human body, the idea is the same. The lower abdomen is like the pot, the breath like the fire, and the Dan Tian the rice. When we keep our breath in the lower abdomen, the fluids in the stomach are heated, and this stimulates the Dan Tian to expand. Like the pot in which the rice is cooked, it must remain undisturbed over the fire in order to cook. Hence, in order to stimulate the qi in the abdomen, it must be done calmly and without forcing the breath.

To give a better understanding of this principle, use a visualization technique by imagining a pot of water within your abdomen, filled to the brim, and then move through the Taijiquan postures with utmost concentration so as not to spill one drop of water from the pot—making no jerking-like motions, no disconnected movements, no leaning, and no sporadic movements. In this way the qi can be calmly stimulated and the mind-intent fully placed in the lower abdomen.

The Chinese character for qi means two things: breath and energy. Energy here means the very source of what animates a human body. Qi is the energy that allows motion in a human being. Therefore, the more powerful the breath is the greater the energy of the body will be, and the more natural the movement and animation of the body will be. For example, a common trick or game you may have played as a child involves standing in a doorway and pressing your hands against the door jambs with great force. If you have ever tried this, you know that when you release your hands from the door, the arms will float upward all by themselves. This is one of the best examples of how the qi animates the body. From creating tension in the arms, you are blocking the qi and blood flow. When you release the pressure on the door jams, the blood and qi rapidly rush back into the arms, creating a movement that is not generated by external muscular force. It is precisely this sensation people should feel in their hands and arms throughout their Taijiquan form practice. If not, then it really isn’t Taijiquan. When the arms feel as if they are floating, the qi is being calmly stimulated.

Another example demonstrating the idea of calmly stimulating the qi is to stand upright with the hands held in front of the thighs, elbows slightly bent, and the shoulders dropped and released of all tension. Focus all your attention into the Dan Tian and simply breathe. This will cause the hands and arms to gradually float and sink according to the breath. After some practice with this exercise, the hands and arms will naturally float up to shoulder level when the breathing is full and strong. In essence, it’s a measure of how strong your qi is.

When about to start performing the Taijiquan form, stand first and just breathe. Let the hands and arms rise and fall according to the breath. This is exactly what is meant by letting the mind first lead the qi, the qi will then lead the blood, and the blood will lead the body. Place all the attention into the Dan Tian, then the breath and qi will follow and generate from the Dan Tian. At this point, the qi mobilizes the blood circulation throughout the entire body, and this causes the body to be capable of creating motion without external muscular force.

To calmly stimulate the qi, you must first put all your attention into the Dan Tian, and this is where the second part of this verse comes in, “so the spirit is retained internally.” Actually, this verse could also read, “When the spirit is retained internally, the qi can be calmly stimulated,” as each stimulates the other.

The meaning of “so the spirit is retained internally” is really defined by the idea of mind-intention. Meaning, when fully focusing on the Dan Tian, or better said, “Abiding by the Dan Tian,” the breath and qi will begin to generate and accumulate in the lower abdomen. Just like with infants, it is not just their abdomen that moves with the breath, but their entire body.

Infants are still generating breath from where the umbilical cord was attached, and over time, as we age, the breath will rise into the lungs. As Daoists say, “the spirit (mind-intention) begins to rise toward the head.”

In Taijiquan, the idea is to reverse this process, so the breath (qi) is led back down into the lower abdomen, where it is with infants. Abiding by the Dan Tian, then, sensing and focusing on the lower abdomen, is the essence of internally retaining the spirit. When breathing in this way, the qi will likewise be calmly stimulated.

In The Mental Elucidation of the Thirteen Kinetic Operations by Wang Zongyue, it is said,

Your mind-intention must be focused on retaining the spirit internally, not on the breath and qi. If your mind focuses only on the breath and qi, the result will be stagnation; you will only have breath, but no strength of the qi.

This passage raises the question on how to breathe while performing the Taijiquan movements. As Master Liang would say, “Don’t worry, by and by you will know it.” This simple answer was not his attempt to avoid the question, but to get a student to let it happen naturally. Just put your attention into the Dan Tian and abide by it. Sensing the lower abdomen, instead of trying to make something happen there, allows the qi to sink naturally into it. No one can force the qi into the Dan Tian; it must be done naturally and with mind-intent.

“Sink” is an important word choice, because it implies no force or expansion of the breath to get the qi into the Dan Tian, just mind-intent and allowing it to sink downward.

The bigger question pertaining to this verse is why do you need to calmly stimulate the qi and retain the spirit internally? Actually, these functions are at the root of mastering all Taijiquan skills—and occur from abiding by the Dan Tian.

To develop the qi, it must first be stimulated calmly. This calm stimulation has its source in the Dan Tian. The qi is calmly mobilized through the circulation of the breath and blood, and the source of doing this is through the mind-intent.

From abiding by the Dan Tian, the qi, breath, and blood begin circulating more fully throughout the entire body and, consequently, are heated. This internal heat then starts affecting the sinews, tendons, and muscles of the body. Once the warm qi, breath, and blood have entered the muscles, they begin to penetrate into the bones and help create more marrow, thus increasing pliability of the bones and leading to greater health.

When the qi circulates freely throughout the body, it can then be directed through the arms and into the hands. This is the true nurturing of qi and it originates with the mind-intent. Therefore, to retain the spirit internally is actually rooted in the principle of sinking the qi into the Dan Tian.

The second benefit from abiding by the Dan Tian can be seen in the self-defense aspects because all the responses will be directed by the waist rather than by the upper body. And, because the reactionary force is generated from the waist, the qi and jin (intrinsic energy) can be more easily expressed as well. Intrinsic energy comes from the sinews and tendons, and so the more pliable and stronger they are, the greater the energy that can be released. When the qi and jin are expressed together, nothing is stronger. Therefore, this verse, “Calmly stimulate the qi, so the spirit is retained internally,” is full of meaning and purpose, and essential to the correct practice of Taijiquan.

Avoid deficiency and excess, avoid projections and hollows, avoid severance and splice.

無 使 有 缺 陷 處. 無 使 有 凸 凹 處. 無 使 有 斷 續 處.

Wu shi you que xian chu. Wu shi you tu ao chu. Wu shi you duan xu chu.

This particular verse must be discussed regarding performing the solo Taijiquan form and the self-defense aspects to acquire a fuller understanding of each of the three avoidances. These three avoidances are a way of saying what not to do to ensure that the instructions of the first line of the treatise are accomplished—With every movement the entire body must be light and nimble, and all of its parts must be kept strung together like a string of pearls.

In other words, if every movement is to be light, then there can be no deficiency or excess in the movements. If every movement is to be nimble, then there can be no projections or hollows when moving. If every movement is to be strung together, there can be no severance or splice taking place. Hence, this verse is actually a kind of mirror, reflecting what causes incorrect movement and function in Taijiquan.

Avoid deficiency and excess: To be deficient means the movement is defective as a result of not correctly applying the ten Tai Ji Quan Principles of Movement , not using your waist to generate a movement, and so forth. For sake of illustration, assume a situation in which you are pushing an opponent, but instead of rising off your rear leg and sinking into your front leg, the weight is retained in the rear leg and your body leans back. This is a deficiency because the method and issuing of energy was defective. Therefore, you could easily be toppled backward. Excess would be the opposite problem. In pushing, there is an extending outward and toward the opponent, but if leaning forward, you could fall into the opponent or be pulled off balance.

In Chinese, the terms que xian (缺 陷, deficiency and excess) as a compound means, “falling into a hopeless situation or trap.” Therefore, if your movements are deficient or excessive it will be easy to fall into the opponent, or off center, and for the opponent to take advantage of the defect. As mentioned, when the feet are light, like the fox walking over thin ice, there is no deficiency; when the feet are nimble, there is no excess. Hence, not finding your root and center of balance when moving is deficiency, and pressing your feet down in order to establish a root is excess.

The principles of Taijiquan can be very subtle at times and therefore difficult to interpret as to what extent they must be applied, especially for a beginning student. For example, the principle of “suspending the head” is often taken too literally and the head is stretched upward. This is excess. To pay no attention and let the head slump down would be deficiency.

If you are practicing the solo form and feel clumsy and sluggish, you are not applying the principles of being light and nimble, and the spirit is not being retained internally. This is deficiency. When the Taijiquan solo form feels like a gymnastic performance, the breathing will become pensive and the muscles tense, and this is excessiveness.

Think of the terms “deficiency and excess” as also meaning “defects and difficulties,” because when things are deficient, defects are created, and when there is excessiveness, difficulties are created.

Avoid projections and hollows: To allow either of these corruptions means that the body is not centered, upright, or relaxed, and the qi and intrinsic energy are being obstructed. Basically, projections and hollows are corruptions of both movement and function. The Chinese terms for projections and hollows are tu ao (凸 凹), which can also be translated as “protrusions and depressions.” Now, protrusions or projections are referring to issues like pushing out the abdomen, pushing the head upward, expanding the chest, straightening the limbs and joints, and so on. Hollows and depressions are exactly the opposite, such as contracting the abdomen, drooping the head, collapsing the chest, or over bending the limbs and joints.

There is a big difference, however, between creating projections and hollows, which are external dysfunctions, and following correct Taijiquan principles of movement, such as “hollow the chest,” “sink the qi,” and “keep the joints slightly bent,” which have to do with internal functions.

Taijiquan principles are subtle, and for the most part are performed internally with mind-intent, not external muscular expressions. For example, the principle of “hollow the chest” means to not trap the breath and qi into the chest, “sink the qi” is rooted in the application of mind-intent, and “keep the joints slightly bent” is not a projection—it is referring to the natural positioning of the body that allows the blood to flow most freely through the joints. No principle could be a defect of either projections or hollows, as they signify the optimal internal functioning of the body.

Ideally, only 10 percent of Taijiquan movement is expressed externally, as 90 percent of the true functioning occurs internally and is unseen by others. Chen Kung in Tai Ji Quan, Sword, Saber, Staff, and Dispersing Hands Combined reiterates this point: “The principles of practice must be kept concealed internally, not expressed externally.”

Avoid severance and splice: In Chinese, duan xu (斷 續) literally means to “separate through breakage.” Severance and splice, then, can occur in body movements, mind-intent, the breath and qi, and issuing intrinsic energy (jin).

In the solo form, the movements must be like a long, flowing river, continuous without jerks or stopping. Splice is an interesting term, because it is like the splicing of a movie film together where there can be no overlapping of images. As in Taijiquan, there can be no overlapping of postures either. The beginning of a posture must be as clear and defined as the end of it.

When performing the Taijiquan solo form (as mentioned earlier), each gesture of a posture should be divided into a count and half-count so that no overlapping of postures can occur. This also prevents the movements from being fast in one count and slower in others. Meaning, the form should be smooth and consistent throughout, and not lose the motion of being strung together.

However, there must still be a slight pause at the end of each posture. This pause is neither an example of severance nor splice, because the mind-intent is not severed. It is just a momentary awareness that the posture has ended so as not to create an overlapping of the movements.

In Sensing Hands practice, severance and splice are the corruptions of Stick, Adhere, Join, and Follow. Stick and Adhere are corrupted by severance, and Join and Follow are corrupted by splice. Stick, Adhere, Join, and Follow were the original meanings of Warding-Off, Rolling-Back, Pressing, and Pushing.

The great Zen teacher, Dogen Zenji, rightly instructed his students by emphasizing the great importance of posture. He instructed that if someone wants to be a Buddha, one must sit like a Buddha, and so the real work of meditation practice is to constantly pay attention to posture, to constantly correct it, and to repeatedly sit to perfect the posturing of the Buddha. The same is true for Taijiquan—applying constant attention to gesture and movements is far more important than being sidetracked by the anticipation of experiencing qi or jin.

When practicing the solo form, thoroughly examine and pay close attention to the correctness of the postures, the gestures within each posture, and the rate of speed applied to the movements. Each beat of a posture must be neither too fast nor too slow, and performed in accordance with the breath. Each movement must be uniform, properly adjusted, strung together, centered, upright, and, most importantly, the entire body made light and nimble. Only through lightness and nimbleness can the words of this treatise be of any functional use. If your movements are not nimble and light, the corrupted practices of deficiency and excess, projections and hollows, and severance and splice will create the conditions for opponents to easily take advantage of you, and you will be unable to catch them unawares.

The energy is rooted in the feet, issued through the legs, directed by the waist, and appears in the hands and fingers.

其 根 在 腳. 發 於 腿. 主 宰 於 腰. 形 於 手 指.

Ji gen zai jiao. Fa yu tui. Zhu zai yu yao. Xing yu shou zhi.

This verse is considered the secret of Taijiquan, at least in the self-defense aspects of the art. No other martial art system makes such exclusive use of deriving energy from the bottom of the feet. Jin (intrinsic energy) comes from the sinews and tendons of the body, and from increased levels of bone marrow. When you have developed your intrinsic energy, you reach a state of Song (鬆) energy, which is akin to the energy of a cat (sensitive, alert, and relaxed). Normally, Song energy is translated into English as just “being completely relaxed,” but it is much more than just that definition. With intrinsic energy comes a very heightened sense of alertness and sensitivity, so the “energy” being referred to in this verse is different than the internal energy of qi.

This verse can be divided into four basic and necessary functions:

1) Rooting the energy into the feet.

2) Issuing energy through the legs.

3) Directing the energy via the waist.

4) Expressing the energy in the hands and fingers.

Intrinsic energy can take on many forms and levels of skills. In Tai Ji Jin, volume 2 in the Chen Kung Series (Valley Spirit Arts, 2013), well over thirty such variations of intrinsic skills are explained. In this verse, the aspect of “issuing energy” (發 勁, fa jin) is being described, and it is the very root of Song energy and the origin of developing the many variants of intrinsic energy and skills. Once the energy can be expressed in the hands and fingers, it can be expressed and issued from any area on the body. So, it is actually not the case that all functions and skills of intrinsic energy be solely expressed through the hands and fingers.

However, until the energy can be rooted in the feet, issued by the legs, directed by the waist, and expressed in the hands and fingers, all the other intrinsic energy skills cannot be developed. It is through these four functions that the entire body is trained to become one complete unit—meaning the aspects of lightness, nimbleness, and all the parts of the body strung together—resulting in a state where Song energy is achieved. Therefore, it is crucial to learn how to issue energy in this manner.

Issuing energy is often described in terms of how a whip functions, as this relates so well to how the body reacts in regards to these four functions and how precisely the principles of Taijiquan interrelate. For example, when lashing out a whip, the length of the whip remains soft and pliable, yet energy is released out the tip of the whip. Likewise, the energy is produced and revealed for only an instant and then disappears. This is exactly how intrinsic energy functions within Taijiquan. The yang is revealed (issued) in an instant and then immediately the body returns to yin again. Intrinsic energy cannot be issued if the body is either constantly yang or yin. To be completely yang is just using external muscular force—this is not intrinsic energy. Nor can you be completely yin, as this is just to be in a state of collapse, not Song energy (sensitive and alert).

Like a rubber band that is stretched out too far, it will snap (extreme yang). If it is not stretched at all, it has no function (extreme yin). Hence, the sinews and tendons of the body are like the rubber band where there is both kinetic and potential energy. They must be developed and exercised properly through Taijiquan practice if the intrinsic energy is to be made capable of issuing out. To use another analogy, issuing intrinsic energy is like a bullet being shot from a gun, with just one instant of yang energy being expressed, and then immediately returning to yin.

This same idea is seen in the practice of Taijiquan sword. From using the entire body as one unit, the entire length of the sword can be made to quiver and vibrate right to the tip of the sword. But those who attempt this without using the whole body as one unit, without relaxing the hand and arm, who grasp the sword handle too firmly, only encounter dead metal. The same is true of training the saber and staff. So, the aspect of training intrinsic energy is paramount in Taijiquan. Indeed, the majority of all Taijiquan practices and principles, be they empty hand drills, two-person exercises, or weapons, the primary function is to aid in the development of intrinsic energy right along with accumulating qi.

Therefore, intrinsic energy, in the analogy of the entire body being perceived as and functioning on the workings of a whip, is indispensable for mastering Taijiquan, and this is not just concerning the self-defense aspects of Taijiquan. This idea is also crucial to the health and longevity aspects as well. From the development of intrinsic energy, blood circulation is increased, sinews and tendons are made strong and viable, and bone marrow is increased—all of which stimulate and mobilize the qi.

Consider the whip handle as being your foot, and when the length of the whip is lashed out, the entire length of the whip is soft, just as your body is soft (yin) as the energy generates from your foot, travels through the legs, and is directed by the waist. Then, just like a whip that releases a strong energy through the tip, the energy issuing through the body appears in the hands and fingers for an instant.

As Yang Chengfu (陽 澄 甫) stated, “You have hands, but it has nothing to do with hands.” Meaning, your hands may touch the opponent, but it is not the hands that push the opponent, rather it is the feet, legs, and waist that actually deliver the strike to the opponent. Like a whip, the energy is delivered or issued quickly, following the Taijiquan ideology that the body is yin, instantly yang, and then immediately yin again.

The statement “directed by the waist” is important because without the correct application of the waist, the intrinsic energy will be obstructed. Although using the waist in Taijiquan is one of those fundamental principles people are taught as beginning students, many practitioners misinterpret this injunction because they were never taught how to properly direct intrinsic energy through their waist. Actually, they were not taught how to properly allow the intrinsic energy through the waist, as the defects in issuing occur from trying to make something happen by applying some external, muscular movement that leads to any of the defects already discussed.

Assume, for example, you are applying Brush Left Knee and Twist Step. Your right hand is attached to the opponent’s left shoulder, your left hand lightly grasps the opponent’s left wrist, and your rear right leg is bent to issue. The energy of the push generates from your right foot and it travels up the leg. As the leg slightly straightens, the hips will naturally open up from the leg rising, which allows the energy to direct through the waist. The waist needs to stay open and relaxed here, otherwise your issuing energy will be obstructed and ineffectual. This is what will release the energy through the waist and direct it into the opponent.

Immediately after issuing the energy out the hands and fingers, the hips close off again as the body sinks and returns to yin. Not to issue in this way will only result in the energy becoming obstructed in the right hip as it tries to pass through the waist. If it doesn’t pass through, then external muscular force must be used to push the opponent.

Why does Taijiquan make use of deriving energy off the bottom of the foot? Aside from the fact that this allows the entire body to strike the opponent, it also makes it impossible for an opponent to detect the intention and attack prior to issuing.

As stated, the analogy of issuing the energy is like the function of a whip, but in reality this is difficult to achieve if the body has not reached some level of Song energy. Just as cracking a whip is not necessarily a given skill either. In cracking a whip, the hand must not grasp the handle too firmly. The whip must be held loosely if the correct motion is to be administered for the length of the whip to extend out and produce energy and sound at the tip. A master of the whip knows that it takes little force to produce the cracking sound. Likewise, it takes very little energy to produce intrinsic energy in the hands and fingers as well.

Enabling the intrinsic energy to reach your hands and fingers unobstructed is half the process, as you must also learn how to properly return to an insubstantial yin state. You must re-establish your root immediately after issuing, otherwise you will be excessive (extended), giving energy to the opponent, and thus create the conditions of deficiency within the movement. If you do not immediately become yin (insubstantial), the opponent has something substantial in you to counterattack or grab onto. Likewise, without immediately returning to yin, you will suffer the case of either double weighting or double floating.

Double weighting, in part, means maintaining the energy (weight, strength, yang, substantial) in the same-side forward leg and arm of the body, thus making it easy for an opponent to take advantage by pulling or grasping the forward arm, or by attacking the front leg. Double floating, on the other hand, means that no energy is maintained (no weight, no strength, yin, insubstantial) in the legs. If, after issuing off your rear leg, the front leg is not rooted and returned to yin, it is like both legs are floating upward with no sense of balance or central equilibrium. In this case, if an opponent attaches or grabs on to any part of your body, in any manner, you will lose your center of balance.

To better demonstrate these two corruptions, perform these two tests with a partner. For double weighting, stand in a Bow Stance with the left foot forward and the right foot back, shoulder-width apart. Bring your left arm out as if pushing outward at the partner and maintain that position. Have the partner seize your left wrist and pull on it. You will find it easy to be pulled and have difficulty maintaining your root.

To experience the effect of double floating, have a partner stand in the same position but with the arms hanging down along the sides. Place a hand on your partner’s chest and then fake a push into his or her body. The result will be your partner rising off both legs onto the tiptoes, and in that instant you can easily knock him or her over because the root has been severed by the defect of double floating.

It is easy to understand how Taijiquan movements contain roundness in the arms, but it is more difficult to see how this applies to the legs and waist. When actually issuing off the rear foot, maneuver your knees and thighs as if they were straddling and turning over a ball. Imagine a large ball with your feet attached to each side of it, and then by simply rolling the ball over, it will stop as one of the feet is touching the ground, and if rolled back the other foot will stop the ball. So, when issuing, either in the solo form or during two-person practices, feel the energy coming up and off the rear leg, through the waist, then down into the front leg—and, lastly, the front foot finds its root.

In teaching students the proper way to move in Taijiquan, former masters almost exclusively used terms like “rise,” “shift,” “sink,” and “seat” to help eliminate the misconceptions and excessiveness from moving upward, downward, forward, and backward. In reality, there are only the actions of rise, shift, sink, and sitting in Taijiquan movements so that central equilibrium is constantly maintained. The Five Activities of Advancing, Withdrawing, Looking-Left, Gazing-Right, and Central Equilibrium are purely aspects, principles, and movements of the feet, legs, and waist. However, the whole idea of both Advancing and Withdrawing function on the actions of rising, shifting, sinking, and sitting. For example, there is a huge difference between shifting into the front leg as opposed to leaning into the front leg. There is a huge difference between rising off the back leg and raising the body upwards (where both legs straighten). There is a huge difference between lowering and adjusting the waist to sink as opposed to bending the knees down. Lastly, there is a huge difference between relaxing the thighs and legs when being seated over the feet as opposed to feeling tension in the legs when doing so.

As mentioned, pressing the foot into the ground is like two solid objects coming together, which can be easily broken or separated. The feet need to be like wet mops, and the legs (calves and thighs) must be relaxed and devoid of tension and strain. Root cannot be gained by simply pressing the feet into the ground, nor by tightening the toes as if to grasp the ground.

When Master Liang was studying Taijiquan in Taiwan, he had the good fortune of meeting with a Daoist priest by the name of Yang (not a member of the Yang Luchan family), who had studied with Yang Jianhou (陽 健 侯) in China before his later escape to Taiwan. With this priest, Master Liang witnessed something he had never seen before with any of his other teachers. Yang could stand on one leg, yet his thigh and calf would remain as soft as cotton. This really impressed Master Liang, and it taught him the enormous gap between what was really meant by hard and soft styles of martial arts. Daoist priest Yang had, in all respects, mastered the principle of sinking all the energy into the Bubbling Well points (on the bottom of the feet), and so could issue and direct intrinsic energy through his legs and waist quite expediently.

Root acts as a person’s center of balance and foundation. With root, a person can apply it to issuing and directing intrinsic energy (jin) for practical use. This skill comes from the foot utilizing the root, and is the secret of Taijiquan.

With a solid root, it’s as if the feet were coiled downward into the ground. The legs easily bend and contract, and the intrinsic energy can issue out and be directed by the waist. When you have root in combination with being light and nimble, all the controlling power can be concentrated throughout the entire area of the waist, functioning as if it were the axle on a cart.

When intrinsic energy appears in the hands and fingers, only then is the energy genuinely being issued (fa jin). So, let the feet be the feet, the legs be legs, the waist be the waist, and the hands be the hands, so that they are all in perfect unity with each other. If they are moved separately, dispersed about like scattered sand, there will be no practical use nor potential to issue.

Therefore, rooting the energy in the feet, issuing it through the legs, and directing it by the waist so it appears in the hands and fingers is a very important principle that leads to high achievement. Pay very close attention to this verse in the text. The significance of uniting the movement of these four parts—feet, legs, waist, and hands—is essential for learning how to gain a root, issue, direct, and exhibit the intrinsic energy.

The feet, legs and waist must act as one unit so that whether advancing or withdrawing you will be able to obtain a superior position and create a good opportunity.

由 腳 而 腿 而 腰. 總 須 完 整 一 氣. 向 前 退 後. 乃 能 得 機 得 势.

You jiao er tui er yao. Zong xu wan zheng yi qi. Xiang qian tui hou. Nai neng de ji de shi.

This aspect of using the feet, legs, and waist as one unit is crucial to both the performance of the solo form and for self-defense. It also demonstrates the proper function of Taijiquan that is completely in the lower body, not the upper. The upper body follows the lower body, or, simply put, the upper body is just along for the ride. All the movements of Taijiquan must first be in the feet, legs, and waist. The feet must be trained so that the insubstantial and substantial aspects can easily be distinguished; the legs must be trained to rise, sink, shift, and step in accordance with the feet; and the waist must always be able to lead and direct the feet and legs. Then you can maintain a superior position and create good opportunities.

An effective method for training the feet, legs, and waist to function as one unit is to perform the entire Taijiquan solo form with the hands held behind the back, leaving you to just focus on the feet, legs, and waist. You will quickly learn how much you rely on your hands and arms. This exercise will strengthen your waist and teach you to pay more attention to all the rises, sinks, shifts, and steps. More than anything else, it really reveals how powerful the waist is and why it is the axletree of all Taijiquan movement.

To further help explain the necessity of using the feet, legs, and waist, practice the following exercise with a partner, first by doing it the wrong way so that the correct method will be much clearer.

Both people face each other. Person B grasps A’s left wrist with his left hand and A’s elbow with his right hand. B then makes a twisting motion with both hands to A’s left arm, which causes A to bend forward and look down at the ground. For all intents and purposes, B can be said to be in total control of A and in a superior position.

A then takes her right hand and arm and strikes up toward B’s face. The normal reaction will be for B to move his head back to avoid being struck, thus losing control over A’s left arm and the ability to take advantage of a good opportunity. This is the wrong way for B to react.

Try the exercise again, but this time when A strikes out the right hand towards B’s face, the correct response is for B to simply sink all the weight into his left leg and foot, and then turn his waist toward the left. This will send A off balance and toward the ground. B, then, takes a superior position and turns it into a good opportunity.

This demonstration will teach you how effective and natural it is to use the feet, legs, and waist, rather than the arms and upper body when reacting to an attack.

Failure to obtain a superior position and create a good opportunity results from the body being in a state of disorder and confusion. To correct this, adjust the waist and legs.

有 不 得 機 得 势 處. 身 使 散 亂. 其 病 必 於 腰 腿 求 之.

You bu de ji de shi chu. Shen shi san luan. Ji bing bi yu yao tui qiu zhi.

When a person doesn’t know how to obtain a superior position and create a good opportunity, the body will always be in a state of disorder and confusion, causing defective movements such as double weighting, double floating, overextension, clumsiness, and loss of central equilibrium. All of these lead to defeat and poor performance of the solo form. However, once you learn how to correctly adjust the waist and legs, these defective movements will not occur. In fact, you will be truly difficult to defeat. This may sound boastful, but once you learn how to react with your lower body, whatever comes at you, you will instinctively be capable of redirecting the force. To quote from the Tai Ji Quan Classic (attributed to Wang Zongyue), you will be capable of “removing one thousand catties with only four ounces of energy,” which results from knowing how to adjust the waist and legs.

The primary reason the body becomes disordered and confused is because of the hands and arms. People seek to defend and protect themselves with the hands first, a natural reaction after years of conditioning themselves to be strong and forceful. It is the hands and arms that cause the upper body to tense, and so the waist and legs are ignored. This is doubly troublesome because the legs and waist are so much stronger than the hands and arms.

Normally, when faced with a threatening situation, people initially react with the upper body, causing the breath to rise into the chest, the mind to freeze, and the hands to immediately move up to protect. Taijiquan, however, trains us to employ the opposite approach. The lower body reacts, the breath is kept low, the mind is calmed, and the waist and legs seek to protect. Yet, it is not the case that the hands and arms aren’t used, they are, but the difference is that they respond in conjunction with the waist and legs. The hands adhere to the attacker to sense the substantial and insubstantial aspects of his or her body, and when the insubstantial is found, the feet, legs, and waist issue (fa jin) to the opponent.

Keep in mind, it is not the hands and arms that try to maneuver and manipulate the opponent, as this would only result in creating tension, resistance, and force. The opponent would then be able to interpret the intent and the encounter would become just a matter of strength against strength, speed against speed, and whoever is not the strongest or fastest will lose the bout. Therefore, in Taijiquan the idea is to redirect an opponent’s force to place him or her into a defective position and to create a superior position for oneself. Thus making it easier to topple the opponent with just four ounces of energy.

But there is much more to learn here than just adjusting the waist and legs, as these only create the superior position and the good opportunity. Next, you must determine what a good opportunity is and how to take advantage of it. For this, three separate applications need explanation, even though they all happen simultaneously when finding a good opportunity.

The first application is called “Affecting the upper, middle, and lower parts of the opponent’s body.” As an example, once again consider the techniques of Brush Left Knee and Twist Step. In this example, person A’s left hand is adhered to person B’s left wrist (whose arm is across his body because A led it there). A’s right-hand fingers are adhering along B’s left flank, and A’s left knee and foot adhere to the outside of B’s right leg.

If, in one instant, A pulls on B’s left wrist in a downward, diagonal manner (affecting the upper part of his body), pushes on B’s left flank with her right hand (affecting the middle of his body), and collapses B’s right leg inward with her left knee (affecting the lower part of B’s body), A puts B in a dire situation of trying to recover and respond to three actions at once. Needless to say, this is nearly impossible for B to distinguish and escape from all three effects.

The second application is “Issuing from the bottom of the foot.” Although issuing has been discussed, note how it would be applied in this situation. If A’s right hand is just adhering to B’s left flank, not pressing in or giving any tension, B will be unable to detect the issuing until after A has pushed him.

The third application is called, “Using a line of attack.” This is much more difficult to explain, but in essence it is knowing where to issue the push so that an opponent has no chance to either find a center of balance or to turn out of the push. If person B, for example, is put in a defective position in which his balance is already being affected, and A pushes on his body in a direction in which B is unable to find a root to remain upright, B is then defeated easily.

Lines are extremely important, and they are what make the really good Taijiquan masters appear to use no energy nor movement to topple opponents. Actually, this is true, as they are not using a lot of energy or movement. They simply don’t need to. What they are using is really good physics.

There are ten variants of lines, but the secret to lines is in knowing how to use them while the opponent is in motion. It is not a matter of person B standing in a fixed stance and person A just walking up to him and pushing on a line so that he falls over. It is all about the motions B makes and the defective positions that A redirects him into.

Therefore, from learning how to adjust the legs and waist, the above three applications can be brought into play to take advantage of a good opportunity and the opponent’s defective position.

Concerning adjusting the legs and waist, I once witnessed an interesting interchange between Master Liang and a so-called Taijiquan master who came to visit Liang at his home. During the visit, the man asked Master Liang about this principle of adjusting the waist and legs. After much side stepping of the question Master Liang was compelled to answer the man. But, as I had learned, if you pestered Master Liang too much on a question, he would demonstrate rather than explain. So, he first had the man stand with his waist turned to the side, with his left arm and leg in the rear. Liang then placed his left hand on the man’s right elbow, and his right hand on his wrist. Liang then pushed on the man’s arm, causing the man to sink further into his left leg. Liang shouted out “Incorrect! You must adjust your waist and legs.”

The man then turned his waist towards Master Liang and while doing so brought up his right arm to attempt to sweep Liang’s hands off of him. But Liang simply folded up his left arm and struck him with his elbow, and then readjusted his waist and legs and sent the man back up against the wall with a push. Lastly, as was his nature, he jovially chided, “You are still wet behind the ears.”

Master Liang then had the man push on him in the same manner, but Liang simply adjusted his waist and legs and adhered his fingertips to the man’s arm, which caused the man to double-weight and to extend his body out and down diagonally. Immediately, Liang gave the man a small push, uprooting him and sending him back. Liang then proclaimed,

The Tai Ji Quan Treatise is very clear: adjust the legs and waist. There is nothing about adjusting the hands and arms. You resisted with your upper body and hands, so it was easy to take advantage of you. If you use your hands like that then you are just “putting legs on a snake” or “removing the pants to fart.” Superfluous actions, young man!

One of the clearest ways in seeing the basic ideas of a “good opportunity” and “superior position” is with the posture Rolling-Back. For example, if person A performs Rolling-Back, person B’s force is directed diagonally downward and away from her, so that B’s waist is turned to the corner and he is leaning his body forward. At this point, A has created a “good opportunity.” When A turns her waist straight ahead, and simultaneously attaches her hands lightly to B’s forward arm, with her weight in the rear leg, this is then a “superior position.” From this superior position, A can issue energy and topple B.

If, however, B has adjusted to a superior position, then A has no good opportunity to exploit. If it happens that A is then in an inferior position, her mind-intent will certainly be in disorder and confusion.

At the time of adjusting the legs and waist to overcome an opponent, this is also the juncture for defeat. Supposing A withdraws and attempts to return to a superior position, but only finds herself falling over, this is because she did not follow with the legs and waist. A must promptly seek to turn and change her legs and waist into a superior position. Immediately, A must issue out the intrinsic energy. Her entire body must be as if all the parts were strung together, along with being light and nimble. Otherwise, there will be no skill or victory.

Only with effortlessness can the simplicity of this function be experienced. It is not easy for the inexperienced to change from an inferior position to a superior one. Therefore, when practicing the round form (the solo movements), change and turn the waist and legs, clearly distinguish the substantial and insubstantial, and pay heed so that each part of your body directly follows the mind-intent. These are the methods for avoiding defeat.

Likewise, upward and downward, forward and backward, leftward and rightward, all of these are to be directed by the mind-intent, and not to be expressed externally.

上 下 前 後 左 右 皆 然. 凡 此 皆 是 意. 不 在 外 面.

Shang xia qian hou zuo you jie ran. Fan ci jie shi yi. Bu zai wai mian.

This verse is an extension of the previous one and is connected to the following one as well. The primary idea here is that no matter if you are in an inferior position about to be toppled or in a superior one seeking to create a good opportunity, any position can be adjusted by the legs and waist. The secret to these adjustments, so to speak, first resides in the mind-intent, not from external movement.

In Chen Kung’s Tai Ji Quan, Sword, Saber, Staff, and Dispersing Hands Combined, the following passage comes from a section titled “Mind-Intent and Qi.”

In regards to the mind-intent, it has been said by some that this is none other than just the mind [rational thinking mind], or that the mind and mind-intent are one in the same. But truly there is both a mind and a mind-intent. These are two separate things and should be thought of as such. The master of the mind is the mind-intent. The mind only acts as an assistant to the mind-intent. When the mind moves, it does so because of the mind-intent, and when the mind-intent arises, the qi will follow. In other words, these three—mind, mind-intent, and qi—in relation to one another, are all interconnected and work together in a rotational-like manner. So when the mind is confused, the mind-intent is disrupted; when the mind-intent is disrupted, the qi is dispersed and insubstantial. So it is said, “When the qi sinks into the Dan Tian, the mind-intent is strengthened and becomes vital; with a strong and vital mind-intent, the mind becomes tranquil.” Therefore, these three mutually employ each other, and in truth they must be united and not allowed to become separated.

What is this mind-intent, and why is it different than mind? Mind-intent, by definition, is the unconscious will and spirit (shen) of a person and it reacts spontaneously and without thought or rational thinking. In analogy, this is similar to the idea of when a person undergoes an adrenal rush and spontaneously acquires the strength to lift a car. There are countless stories of people doing such feats during a crisis, and even though science credits this to adrenals, it is the mind-intent that initially stimulates the adrenals.

For purposes here, however, the mind-intent is purely a question of a natural, spontaneous, and trained response to a situation wherein the thought process is overridden. Meaning, after a long period of practicing Taijiquan your body will move and react without any initial rational and calculating thoughts. It just moves.

It is said that Yang Panhou while sleeping threw a rat off his body, splattering it against the wall. When the students came to check on him in the morning he was fast asleep, and when awoken, he had no recollection of the rat. This is a function of mind-intent. As the Mental Elucidation of the Thirteen Kinetic Operations states, “So sensitive and alert not even a fly can alight.”

Yang Luchan while sitting by a river meditating was attacked from behind by a man, and without any external movement he repelled the man away. These are all examples of the function of mind-intent.

Actually, every time you tie your shoelaces and hold a conversation at the same time, this is a function of mind-intent. When we were younger and first learning to tie our shoes, it took great thought and calculation. After years of doing it, however, we no longer need to think about it. We use mind-intent a great deal in our daily lives, but because certain actions are so routine and mundane, we give them no conscious thought.

Therefore, when we perform Taijiquan with mind-intent, the qi can move freely throughout the body and the mind can be tranquil, without conscious thoughts, as we no longer need to focus on the movements. In other words, the process of thinking obstructs the qi from flowing and the mind-intent from functioning.

The Tai Ji Quan Classic states, “The mind-intent is like the commander of an army, the qi is like his officers, and the mind is like the troops.” If the troops are unruly and fail to follow the dictates of the officers and commanders, all then is disrupted. But if the mind-intent (commander) is made strong and vital, both the officers and troops will obey their orders and the army can function smoothly and without error.

The mind-intent is the cornerstone and an absolute necessity of correct Taijiquan function. The solo form or any of the other exercises must function on the mind-intent. No one can mobilize the qi or issue intrinsic energy purely with rational thought and calculation. Rather, mind-intent is an action so spontaneous it is devoid of all preconception and thought. Achieving mind-intent in Taijiquan is difficult, to say the least, and takes many years of practice.

Mind-intent is the essence of what is meant by “internal.” Many internal stylists, from martial artists to meditators, erroneously consider that if they are concentrating on the Dan Tian, inhaling and exhaling while visualizing qi, and so forth, they are somehow practicing the internal arts correctly.

However, nowhere in any of the Taijiquan classical writings is it stated that the qi leads or dictates the mind-intent. The qi, in reality, can only be developed and mobilized through mind-intent. Attempting to find spontaneity and perfection of movement through concentrating on the breath, visualizations, or techniques will only confuse and bring disorder to the mind-intent and qi. Mind-intent is not the product of focusing on the qi or any of the intrinsic energies developed in Taijiquan. Conversely, all these are products of mind-intent.

Using the breath, visualizations, and techniques to acquire mind-intent and qi is like the anecdote in the Zhuang Zi, “Traveling north to Chu by heading south towards Yue.” Meaning, someone wishing to travel to a southern destination by heading in a northern direction. Unfortunately, many Taijiquan students are taught to follow this futile path and so end up doing nothing more than relying on externals. Their forms may look like Taijiquan, but in reality are just exercises in gymnastics and calisthenics.

Master Liang always emphatically declared that “only 10 percent of the movement in Taijquan should be visibly seen, the other 90 percent occurs internally and is unseen.” This is all a matter of mind-intent, and with 90 percent of your movement occurring internally, it doesn’t leave much room for fancy, exaggerated, and external movements.

Admittedly, in my ignorance, when I first started learning Taijiquan with Master Liang I wasn’t impressed by his Taijiquan movements whatsoever. He was old, 82 at the time, and moved in a very compact and seemingly unenergetic way. It looked nothing like I had envisioned Taijiquan movements to be. However, I soon learned that he was functioning more on mind-intent than external movements. After forty-plus years of practice and from his age, the movements really were internalized.

On one particular occasion, I remember practicing the Taijiquan form with him. I was going through the form in a very expanded, flowing, and energetic manner. He just moved very compactly and unenergetically. When we were finished with the form he turned to me and said, “Beautiful, your Taijiquan movements are much better than mine.” I was so proud of myself and arrogant enough to say at that time, “Yes, I felt like I was moving in the wind.”

Liang then immediately chided me, “Yes, if you mean like passing wind. You bloody idiot that was only an external display of Taijiquan. Nothing was internal, and I saw everything, including your breath. How pitiful!”

He then walked calmly past me as if to leave the room, but seized my arm and threw me to the floor instantly without breaking his stride. Grinning down at me, he said, “Ready to be beaten and crushed into a pancake. Practice more, and learn to calmly stimulate your qi, then there will be hope for you.”

No single explanation or word can fully define mind-intent. Yang Chengfu likened it to “meditation in action.” Yet, the concept of this goes much further than just a focused and quiet mind. Rather, it is a mind in thoughtlessness, an abstract state of mind devoid of form, perception, consciousness, activity, and thought. Chan Buddhists consider it a form of samadhi, and Daoists as wei wu wei (active non-action). To the Taijiquan adept, mind-intent is the perfection of movement and spontaneity within tranquility, wherein movement and stillness are one in the same (“not two”).

Master Hsiung Yanghou referred to it as the “one action” (一 氣, yi qi). Philosophically, yi qi is considered the point or stage where yin and yang are in complete harmony, where the breath and body are one, where the body and mind-intent are one, where the mind and body are one complete unit. Basically, it means the body, mind, qi, mind-intent, and movement all become one action, not separate ones.

Master Liang was never very philosophical about explaining mind-intent. His advice on the subject, especially to beginners was more frustrating than clarifying, and was always the simple advice of “just practice, relax, and by-and-by you will come to know it. Just use your imagination, then gradually it will become reality.”

Taijiquan is a matter of how Lao Zi in The Scripture on the Dao and Virtue explained inner cultivation, “Cultivation is a matter of subtraction, not addition.” This is the only way.

How can you learn to yield and lose by constantly trying to gain and win? People who talk about big secrets only fool themselves and others. They’re just imposters. Taijiquan is so simple, so spontaneous that the genius completely overlooks it. So don’t try to be clever. Use your imagination, not your clever mind and strength, then gradually it will all become a reality. Just like Lao Zi said,

When the mind rests in a state of nothingness, we can look at the inner enigma; when the mind tries to manifest an inner state of some kind, we can only see the outer manifestations.

In other words, by only paying attention to external expressions, we never realize the internal expressions. Mind-intent leads the qi, and this is the internal expression; the qi leading the body is then the external expression. But too many students attempt to do the opposite, erroneously thinking the body can lead the qi and the qi can lead the mind-intent. Only through the mind-intent, can the internal and external become “one” (yi qi).

Assuming that a person has already and completely unified the entire body and four limbs, there will then be a firm foundation for understanding how to adjust the legs and waist in any of the six directions—upward and downward, forward and backward, and leftward and rightward—each of which are of equal importance.

The text here is ultimately stating that the feet, legs, waist, shoulders, spine, and even the hands and fingers are to follow not only the principle of yi qi, but to likewise train, focus, and strengthen the mind-intent so that every part follows its dictates. Then you can succeed in reaching a stage where the Six Unions, internally and externally, are all one in the same. It is at this stage you can find complete spontaneity and perfection of movement where the body moves in accordance with the mind-intent.