[4]

PRINT CULTURE AND THE EMERGENT PUBLIC SPHERE IN COLONIAL TAIWAN, 1895–1945*

LIAO PING-HUI

[F]or a true collector the whole background of an item adds up to a magic encyclopedia whose quintessence is the fate of his object. … [C]ollectors are the physiognomists of the world of things—turn into interpreters of fate.

—Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library”

[N]ewspapers everywhere take “this world of mankind” as their domain no matter how partially they read it.

—Benedict Anderson, The Spectre of Comparisons

THE TANAKA COLLECTION AND THE “ANGEL OF [POST]COLONIAL HISTORY”

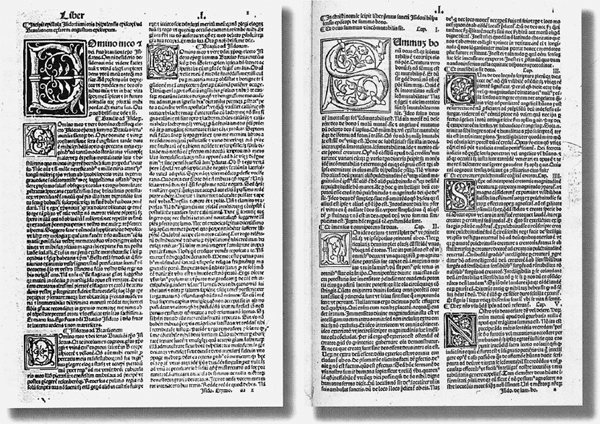

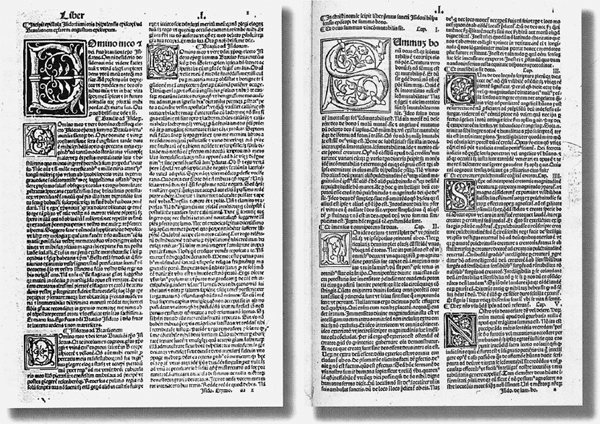

On March 6,1929, the renowned German botanist Otto Penzig (1856–1929) died in Genoa, Italy, leaving behind him a rich collection of old books and periodicals on citrus fruits and other related subjects that contained studies dating from antiquity up to the era of Carolus Linnaeus (1707–1778). Among the 2,446 titles and 3,326 volumes,1 four are especially valuable, as they were printed between 1480 and 1499, only a few decades after the Gutenberg Bible (1456): Regimen sanitatis salernitanum (Venice, 1480) by Arnaldi de Villanova (1240–1311); Il Libro della agricultura (Vicenza, 1490) by Pietro de Crescenzi; Etymologiarum et De summo bono (Venice, 1493) by Isidorus Hispalensis (560–636); and De virtutibus herbarum (Venice, 1499) by S. Avicenna (980–1037).

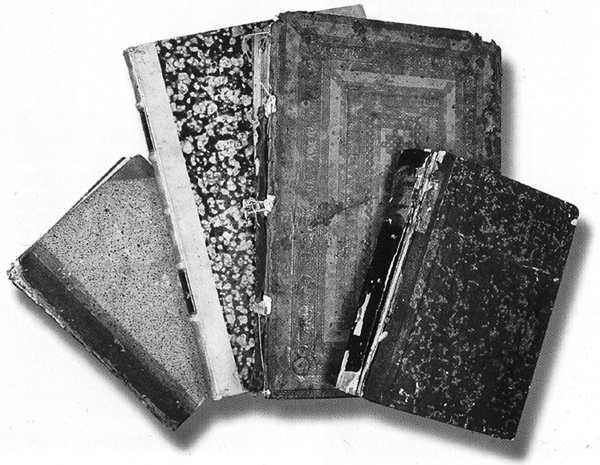

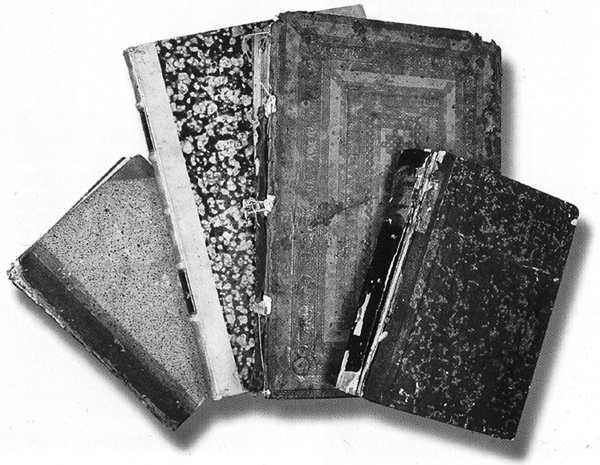

Penzig’s private collection was auctioned upon his death and soon sold through an agent to Tanaka Tyozaburō  (1885–1976), then professor in the agriculture division of Taipei Imperial University (the forerunner of the National Taiwan University, hereafter abbreviated as TIU). Tanaka had just been appointed the first university librarian (1929–1934) and was charged with starting to build the university’s collection. An eminent Japanese orchard horticulturalist, Tanaka came from a very wealthy family—his father, Tanaka Tashichirō

(1885–1976), then professor in the agriculture division of Taipei Imperial University (the forerunner of the National Taiwan University, hereafter abbreviated as TIU). Tanaka had just been appointed the first university librarian (1929–1934) and was charged with starting to build the university’s collection. An eminent Japanese orchard horticulturalist, Tanaka came from a very wealthy family—his father, Tanaka Tashichirō  , was the founder of Kobe Bank—and used US$100,000 of the inheritance from his father to purchase the Penzig Collection in 1930 (figs. 4.1 and 4.2).

, was the founder of Kobe Bank—and used US$100,000 of the inheritance from his father to purchase the Penzig Collection in 1930 (figs. 4.1 and 4.2).

In his capacity as librarian, Tanaka arranged the purchase of several precious collections, among them the Inō  , Huart, U-shih-shan-fang

, Huart, U-shih-shan-fang  , Ueta

, Ueta  , Momoki

, Momoki  , and Nagasawa

, and Nagasawa  collections,2 thereby making the TIU library one of the best in East Asia. The Inō Collection, for one, is the most comprehensive collection of materials concerning the Pacific Asia region under the South Advance Project launched by the Japanese government in its attempt to expand Japanese imperial forces before the Second World War to include the Philippines and Solomon Islands. To this day, the materials in the Inō Collection are most useful for the study of the aborigines in Taiwan.

collections,2 thereby making the TIU library one of the best in East Asia. The Inō Collection, for one, is the most comprehensive collection of materials concerning the Pacific Asia region under the South Advance Project launched by the Japanese government in its attempt to expand Japanese imperial forces before the Second World War to include the Philippines and Solomon Islands. To this day, the materials in the Inō Collection are most useful for the study of the aborigines in Taiwan.

The Penzig Collection, however, held a special place in Tanaka’s heart. Not only did he place bookplates in memory of his father in each of the books, but he carried on the unfinished project of classifying and naming species by updating this material in the manuscripts. Tanaka, a notable agronomist himself, drew and catalogued trees and crops that he discovered in Taiwan and elsewhere during field trips, mostly by adding real-sized portraits of specimens to the volumes. The accumulated pictures detailed the process of Taiwanese oranges recovering from various types of termite bites and worm attacks; they helped establish Tanaka’s reputation in his field. When the Japanese emperor acknowledged defeat and gave up sovereignty over Taiwan in 1945, Tanaka left his collection and manuscripts behind as the Kuomingtang (KMT) government declared them the property of National Taiwan University. In the 1960s Tanaka returned to Taipei to claim the Penzig Collection and his manuscripts. He was told that the collection belonged to NTU and that his drawings had been mistaken for useless cardboard. They had been cut up and distributed to schoolchildren for use during their art lessons at a time when the supply of good-quality sketch paper was deficient. Tanaka gave up his claims, although he found the results difficult to accept. He never visited Taiwan again and died in 1976.

Several elements are synecdochically revealing about the historical trajectories in which Taiwanese print culture became more developed under the Japanese colonial regime. First of all, small if historically contingent incidents like the death of Otto Penzig and Tanaka’s inheritance helped make the Penzig purchase possible and contributed to the enrichment of the TIU library collection. 1929 was a crucial year, in which Tanaka became university librarian and had both the chance and the desire to purchase more books.

Second, in this exceptional case of colonialism and modernity, the ambivalent roles of colonizer and benefactor, of librarian and collector, played out in several diverse arenas, among them public/private resources, personal/transnational predicaments, colonial and postcolonial situations. Like Penzig, Tanaka kept the collection personal even though he used the TIU library space and staff to catalogue his new possessions. He apparently didn’t intend the books to be public property or part of the library collection. However, the semiofficial and problematic status of the Penzig Collection in the library put Tanaka in an awkward position when he tried to reclaim what had originally been purchased under his name. The question was further complicated by Japan’s defeat, which left Tanaka a victim of transnational deals. These personal and historical mishaps ironically made Tanaka a contributor—albeit unwillingly—to the NTU library collection.

FIGURE 4.1 Tanaka Special Collection: the fifteenth-century incunabula.

FIGURE 4.2 Regimen sanitatis salernitanum (1480), by Arnaldi de Villanova (1240–1311).

Librarians such as Tanaka thus helped build both valuable and comprehensive collections of material on modern social and technological issues, slowly albeit unconsciously paving the way for Taiwanese students to develop cultural literacy. Three major libraries in the Japanese period were instrumental in this regard: the archival material of the colonial government library, the special collections and modern library of TIU, and books on various subjects in the Taichung public library. Together with newspapers and journals, these libraries made texts in Japanese, Chinese, and a rich diversity of European languages available to Taiwanese scholars as well as the general public.3 Motivated by the colonial assimilation policy, newspapers were published in bilingual forms from the time they were launched in 1896, with approximately eight pages in Japanese and two to three pages in Chinese translation (and one page designated for advertisements or public announcements). Common readers thus gained access to global and local news or information, and acquired modern cultural knowledge and skills. And because higher education was promoted, especially with the establishment of normal colleges and of TIU, private and public libraries were filled with books from Japan and Europe. In this regard, then, Tanaka’s library project went hand in hand with the introduction of print culture and literacy at the time.

Third, the Tanaka incident is also a representative case of colonialism and modernity. Tanaka came to TIU largely because of the interests, power, and prestige that the colonial regime provided. His stipend at TIU was 60 percent more than he had drawn at Kyushu Imperial University, not to mention other subsidies and benefits.4 The relatively “marginal” location of Taiwan gave him more freedom to collect research materials and books that would otherwise have been beyond his reach. It was colonial policy that TIU should have a library collection equivalent to what Tokyo Imperial University was purchasing at the time. This explains why NTU now has many good editions and rare books on European literature and philosophy in its special collections section, such as Naturalis Historiae (Venice, 1479) by Caius Secundus or the limited corrected version of Heidegger’s Sein und Zeit. This is of course a legacy of the assimilation policy introduced by Izawa Shuji  , the first minister of academic affairs under the Taiwan governor-general, and realized in July 1898, when the “Regulations concerning Taiwan public schools” were promulgated to familiarize the Taiwanese with the “national” Japanese language and culture, and when three systems of schooling were adopted—Japanese, Taiwanese, and aborigine—to reinforce racial differences.5

, the first minister of academic affairs under the Taiwan governor-general, and realized in July 1898, when the “Regulations concerning Taiwan public schools” were promulgated to familiarize the Taiwanese with the “national” Japanese language and culture, and when three systems of schooling were adopted—Japanese, Taiwanese, and aborigine—to reinforce racial differences.5

Founded in 1928, TIU followed the colonial government’s educational policy by employing a majority of Japanese professors to more “effectively” advance learning even though Taiwan was held to be an “extended” part of Japan, a part of the “interior.” In 1928, when Tanaka joined TIU, only 6 Taiwanese were enrolled, while 49 Japanese formed the main student body. It is against this background of racial inequality and discrimination that Tanaka taught his disciples agronomy and built his public as well as private collections. The situation changed when his home country was defeated and the university was handed over to the KMT government from China. His private collection was then declared to be public property. Because of anti-Japanese sentiments, the Tanaka, Inō, and other collections were actually left abandoned in the basements of the general and research libraries for almost half a century. It was not until Lee Tenghui  became president and launched a “Taiwanization” movement that the collections, by then heavily deteriorated and in deplorable conditions, drew attention again. History thus plays another traitorous and naughty trick on the collector, making narration of the colonial and postcolonial histories increasingly difficult.

became president and launched a “Taiwanization” movement that the collections, by then heavily deteriorated and in deplorable conditions, drew attention again. History thus plays another traitorous and naughty trick on the collector, making narration of the colonial and postcolonial histories increasingly difficult.

The Tanaka case shows Walter Benjamin to have been correct when he associated history with an “automaton constructed in such a way that it could respond to every move by a chess player with a countermove that would ensure the winning of the game” or with a “hunchbacked dwarf—a master at chess—[who] sat inside and guided the puppet’s hand by means of strings.”6 The relationship between colonialism and modernity is a “no-win game.” Taiwan print culture, our more immediate concern here, has a more complex story to tell than simply a victim’s tale or a celebration of moral good luck.

If we were to rewrite Benjamin’s story of the “Angel of History” in a postcolonial hindsight, this is how one could picture the angel and the collector. His face turns away from the past. Where we perceive a chain reaction of events, he sees catastrophes—among them the February 28 Incident—which keep piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurling them in front of his feet. The angel would like to move, awaken the dead, and make use of what has been collected. But a storm is blowing, propelling the angel into the future, to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris and ruins grows underneath him.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF PRINT CAPITALISM IN COLONIAL TAIWAN

Print culture—”a new way of linking fraternity, power, and time meaningfully together … which made it possible for rapidly growing numbers of people to think about themselves, and to relate themselves to others”—includes newspapers, books, and any form of printed material that helps promote literacy and a sense of an imagined community.7

Chinese books were brought to Taiwan when Ming loyalists such as Shen Guanwen  followed Koxinga

followed Koxinga  there. Shen and twelve other exiled literati formed a literary society called Dongyin

there. Shen and twelve other exiled literati formed a literary society called Dongyin  (Reciting in the East) and saw to the distribution of their poems. In fact, even before the Chinese immigrants and exiles came to the island, Dutch missionaries had introduced the aborigines to the Bible and provided a translation of the New Testament in one of the local languages. The style of printing indicates that the printers may have come from the Fukien province of southern China.

(Reciting in the East) and saw to the distribution of their poems. In fact, even before the Chinese immigrants and exiles came to the island, Dutch missionaries had introduced the aborigines to the Bible and provided a translation of the New Testament in one of the local languages. The style of printing indicates that the printers may have come from the Fukien province of southern China.

However, it was only in 1895, when the Japanese colonial government took command and began its rule, that colonial officials on the island proposed printing a Japanese newspaper. On June 17, 1896, the first anniversary of the “initiation” of Japanese rule, Taiwan shinpō  (Taiwan News) was launched. One of its goals was to satisfy the needs of the Japanese in Taiwan who had developed newspaper-reading habits back in Japan. It also aimed to report important events as they occurred. The Meiji era is famous for its modernization project to “popularize” Western knowledge and national news.8 Taiwan shinpō was inspired by just such a spirit, and in order to succeed it had to import everything from Japan to Taiwan—machinery, printers, and even paper were shipped directly from the homeland.9

(Taiwan News) was launched. One of its goals was to satisfy the needs of the Japanese in Taiwan who had developed newspaper-reading habits back in Japan. It also aimed to report important events as they occurred. The Meiji era is famous for its modernization project to “popularize” Western knowledge and national news.8 Taiwan shinpō was inspired by just such a spirit, and in order to succeed it had to import everything from Japan to Taiwan—machinery, printers, and even paper were shipped directly from the homeland.9

According to Li Cheng-chi  , between 1898 and 1900, Taiwan news paper and media culture underwent a second structural transformation by going public. As sanctioned by the governor-general, Kodama Gentarō

, between 1898 and 1900, Taiwan news paper and media culture underwent a second structural transformation by going public. As sanctioned by the governor-general, Kodama Gentarō  , and civil officer Gotō Shimpei

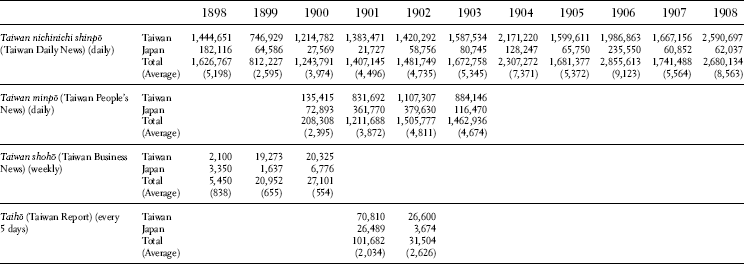

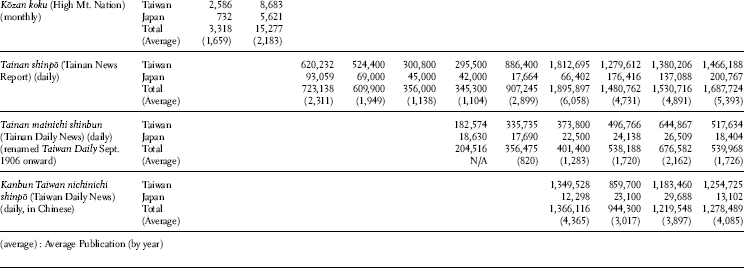

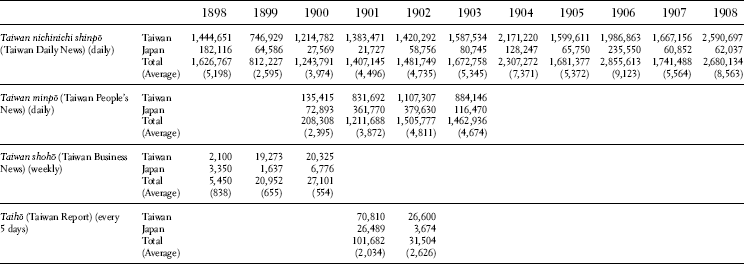

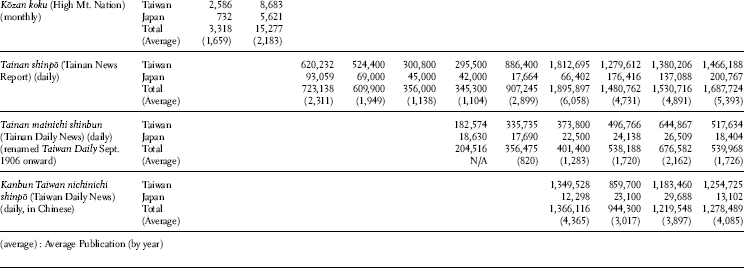

, and civil officer Gotō Shimpei  (1857–1929), the right to operate news papers was handed over to Japanese commoners in Taiwan, who collected capital and ran their businesses according to market logic. Public opinion was galvanized for the first time to criticize the colonial regime in Taiwan, and interest shifted to local issues in order to attract the attention of readers and consumers located in three cities—Taipei, Tainan, and later Taichung. From 1898 onward, local news papers in Japanese had a much wider circulation in Taiwan than in Japan (see tables 4.1 and 4.2 for durations and circulations).

(1857–1929), the right to operate news papers was handed over to Japanese commoners in Taiwan, who collected capital and ran their businesses according to market logic. Public opinion was galvanized for the first time to criticize the colonial regime in Taiwan, and interest shifted to local issues in order to attract the attention of readers and consumers located in three cities—Taipei, Tainan, and later Taichung. From 1898 onward, local news papers in Japanese had a much wider circulation in Taiwan than in Japan (see tables 4.1 and 4.2 for durations and circulations).

Even though the newspapers and weeklies or periodicals were in Japanese, anti colonial sentiments and cultural criticism prevailed in their pages, and corruption in the colonial government was exposed and satirized in political cartoons. Of course, from 1898 to 1945 the colonial government continued prepublication censorship and banned any printed material (and from 1930, films as well) that appeared to conflict with the interests of the colonial regime or of the Japanese emperor. Documents show that police stations were piled with censored books and news articles.10 Together with censoring and banning the import of dangerous items from Japan, the colonial government resorted to all sorts of means both to promote news media that supported the regime and to repress the public sphere.

TABLE 4.1 Histories of Major Newspapers in Colonial Taiwan

= One of three newspapers for Imperial use in Taiwan

= One of three newspapers for Imperial use in Taiwan

= One of the nonofficial newspapers funded by the Japanese living in Taiwan

= One of the nonofficial newspapers funded by the Japanese living in Taiwan

= One of the “yellow” newspapers in the 1930s (notorious for reporting on violence, murders, rapes)

= One of the “yellow” newspapers in the 1930s (notorious for reporting on violence, murders, rapes)

Table provided with the assistance of Li Cheng-chi.

TABLE 4.2 Average Publication of Major Newspapers in Colonial Taiwan

It has often been assumed that the colonial government had Taiwan nichinichi shinpō  (Taiwan Daily News) on its side, countered by Tai oan chheng lian

(Taiwan Daily News) on its side, countered by Tai oan chheng lian  (Taiwan Youth, 1920) and Taiwan shin minpō

(Taiwan Youth, 1920) and Taiwan shin minpō

(Taiwan People’s News, 1923), which were introduced by Taiwanese intellectuals. However, a detailed analysis of the content of the newspapers and journals shows that ideology might not have been an important motivation. In early issues of the so-called official newspaper Taiwan nichinichi shinpō, several Taiwanese publically demanded the right to challenge or correct “untruthful reports,” and by 1910 half of the advertising sections were devoted to Taiwanese goods. Apparently long before 1910, the public sphere had come into being even within the news media controlled by the colonial government. We may well describe this institution of public opinion and anticolonial discourse as “anamorphosis” (as defined by Jacques Lacan) or “unbound seriality” (which Benedict Anderson found to be ubiquitous in tracing the development of nationalism and cosmopolitanism in media dialectics at home and in the world).

(Taiwan People’s News, 1923), which were introduced by Taiwanese intellectuals. However, a detailed analysis of the content of the newspapers and journals shows that ideology might not have been an important motivation. In early issues of the so-called official newspaper Taiwan nichinichi shinpō, several Taiwanese publically demanded the right to challenge or correct “untruthful reports,” and by 1910 half of the advertising sections were devoted to Taiwanese goods. Apparently long before 1910, the public sphere had come into being even within the news media controlled by the colonial government. We may well describe this institution of public opinion and anticolonial discourse as “anamorphosis” (as defined by Jacques Lacan) or “unbound seriality” (which Benedict Anderson found to be ubiquitous in tracing the development of nationalism and cosmopolitanism in media dialectics at home and in the world).

Drawing on Baltrusaitis’ book on Hans Holbein’s intriguing The Ambassadors, Lacan suggests that the distorted fetus-like shape in the foreground of this painting is not simply a skull or even the dread of death but “a trap for the gaze,”11 a gaze “imagined by me in the field of the Other,”12 the illusion of “seeing itself seeing itself” in the “inside-out structure of the gaze.”13 The phenomenon that he calls “anamorphosis” involves the projection of one’s fears and anxieties (of annihilation and of castration) onto an “oblique” surface to produce a “figure enlarged and distorted according to the lines of what may be called a perspective.”14

In the case of Japanese newspapers in Taiwan and their discursive practice of doing cultural critique from the inside out, of exposing corruption from a transnational perspective, the anamorphic vision was constructed around power struggles at home between Tokyo imperialists who supported the occupation of Taiwan and Kyoto radicals who were in favor of giving up Taiwan or even of trading Taiwan to China or any foreign nation for a billion yuan to avoid further budgetary deficits.15 Fiscally, the 1896 tax income from Taiwan amounted to two and a half million yuan (2,710,000) while keeping the colonial government running required almost seven million yuan (6,940,275). During the following two years, aid from the Japanese government also neared six and four million yuan, respectively.16

Printed in Taiwan and circulated in Taiwan and Japan, newspapers like Taiwan nichinichi shinpō criticized the colonial government in Taiwan in rather harsh terms. Two political cartoons, for example, satirized the colonial officials’ grand narratives of their accomplishments in the colony, and laid bare the corrupt official strategies of containment by using a pretty-looking jar to store rotten fish (see figs. 4.3 and 4.4).

FIGURE 4.3 Political cartoon: “Rotten fish stored in a pretty-looking jar.” From Kōzan Koku, extra-vendor no. 3, February 17,1899,15.  ,

,  . “Even if covered up it still stinks; it just wont’t shup up.” “Try to cover it up with one more piece of paper.” [The paper is aptly entitled “peace and prosperity.”]

. “Even if covered up it still stinks; it just wont’t shup up.” “Try to cover it up with one more piece of paper.” [The paper is aptly entitled “peace and prosperity.”]

On the basis of newspaper circulation numbers, it appears that more Taiwanese were reading such newspapers and learning from the anamorphic visions of Japanese politicians and intellectuals in order to cultivate both their own literacy and their consciousness of an incubating civil society. Entries in an 1899 diary by Zhang Lijun  , a town clerk at Fengyuan in Taichung county, show that he was a dedicated subscriber to and an avid reader of both the Taiwan nichinichi shinpō and the Taiwan shinbun

, a town clerk at Fengyuan in Taichung county, show that he was a dedicated subscriber to and an avid reader of both the Taiwan nichinichi shinpō and the Taiwan shinbun  (Taiwan News) from as early as 1900.

(Taiwan News) from as early as 1900.

FIGURE 4.4 Political cartoon: “Evoking the false deity to fend off criticism.” From Kōzan Koku, extra-vendor no. 5, October 28, 1899, 10.

. Hudō Daimeiō (punning on Gotō): “While evoking the false deity to fend off criticism, Gotō heard the voice from above: ‘Thou Shalt Not.’”

. Hudō Daimeiō (punning on Gotō): “While evoking the false deity to fend off criticism, Gotō heard the voice from above: ‘Thou Shalt Not.’”  .

.

After his retirement from a small office job, Zhang kept his newspaper-reading habit.17

According to Anderson, a newspaper or periodical makes national as well as world news available to its readers and performs an everyday institutional modeling by not only reporting news stories that are quotidian universals but also by translating events as they happen elsewhere into comprehensible and relevant codes or discourses for local readers.18 Early Japanese language newspapers and periodicals allowed Japanese subscribers to see themselves via anamorphic visions while at the same time opening up possibilities for Taiwanese readers to connect with the outside world and to acquire a standardized modern vocabulary.

It is small wonder that by 1920 news media such as the Taiwan shin minbō (Taiwan People’s News) very openly published Taiwanese views and critical opinions, and when the newspaper was issued daily it published many popular and imaginative fictional works representing social realities in addition to providing news reports and commentaries. Schools and public places were major sites where new newspaper literary works circulated. In several recent collections of oral narratives, public school teachers are said to have used newspapers articles in their classrooms. Together with the newspaper distributors, school libraries, hospitals, and other communal public facilities provided billboards for common readers.

As the news media rapidly expanded and evolved, more Taiwanese became subscribers to daily newspapers than to weekly periodicals. Statistics show that the print media on the island grew at such an accelerated speed that by 1937 there was practically one newspaper sale or subscription for every 34.41 Taiwanese. In the same year the total annual sale of newspapers imported from the metropolitan territory of Japan amounted to fifteen million copies, with Taiwanese newspapers taking up to 42.9%.

It is estimated that in Asia the literacy rate in Taiwan in 1930 was second only to that of Japan.19 Though censorship and discrimination kept local Taiwanese from receiving a higher education, rich businessmen and the cultural elites sent their children to high schools and colleges in Japan. A checklist of publications by Taipei county writers between 1920 and 1945 catalogued thousands of poetic and fictional works that appeared in literary magazines and were made available by publishing houses.20 It is apparent that during this period magazines, books, and the news media were becoming commonplace in Taiwanese people’s daily experience.

ANAMORPHIC VISION AND COSMOPOLITANISM

Newspapers and the media had since 1895 become the domestic battleground for Japanese wars fought on distant fields—Taiwan, Manchuria, Korea, and even Okinawa. Officials and statesmen survived political struggles first by doing remarkably well in the colonies—particularly in Taiwan, as in the case of Gotō Shimpei, who modernized the systems of census, public health, and infrastructure, among other things—and then by overturning their opponents at home when the latter made wrong judgments or moves about riots in the colonies. The transnational or transcolonial character of the news media thus brought about anamorphic visions of seeing colonizers seeing themselves and of envisioning the colonized seeing their “masters” exposed by their colleagues from afar.

Often the rivalries and tensions between the military and the civilian officials in the metropolis were acted out in and displaced and distorted onto the colony. In spite of Gotō’s achievements in modernizing Taiwan, he was faulted for failing to realize his colonial policy regarding localization and incorporation. Because of such criticisms launched against him from home, Gotō was recalled. Although he was later cleared of accusations, he was not able to form his cabinet in spite of his popularity as minister of transportation.21

In October 1919, with the death of the seventh governor-general, Lieutenant-General Akashi Motojirō  , Prime Minister Hara Kei

, Prime Minister Hara Kei  was finally able to appoint Den Kenjirō

was finally able to appoint Den Kenjirō  (1919–1923) as Taiwan’s first civilian governor-general to bring into effect his reforms in the colony. Hara Kei’s rise to power greatly depended on using Taiwanese news media to expose corruption and violence in the colony.

(1919–1923) as Taiwan’s first civilian governor-general to bring into effect his reforms in the colony. Hara Kei’s rise to power greatly depended on using Taiwanese news media to expose corruption and violence in the colony.

The second feature of Taiwan’s news media between 1895 and 1945 is the “unself-conscious” modernization process it brought about in modeling readers and citizens to follow national and international news in serialization, and in standardizing new vocabulary in such areas as the economy, technology, cultural literacy, and political representation. In addition to channeling the anamorphic vision back and forth between the metropolitan center and the colonial peripheries, the news media of the time also reported local and foreign events, thus providing the Taiwanese a cosmopolitan knowledge of the modern world.

As advanced by Anderson, newspapers embody two interconnected principles of coherence: worldliness and universality.22 No matter how partially readers may be able to decode messages in the media, “newspapers everywhere take ‘this world of mankind’ as their domain” and override formal boundaries. “In Misbach’s era, Peru, Austro-Hungary, Japan, the Ottoman Empire—no matter how vast the real differences between the populations, languages, beliefs, and conditions of life within them—,” Anderson suggests, “were reported on in a profoundly homogenized manner.” “Tenno there might be inside Japan, but he would appear in newspapers everywhere else as (an) Emperor. Gandhi might be the Mahatma in Bombay, but elsewhere he would be described as ‘a’ Nationalist, ‘an’ agitator, ‘a’ [Hindu] leader. St. Petersburg, Caracas, and Addis Ababa—all capitals. Jamaica, Cambodia, Angola—all colonies.”23

This kind of “unself-conscious” modeling character of the media brings us back to the “unself-conscious” albeit “unwilling” contribution of Tanaka to NTU’s library collection. In fact, when Tanaka tried to catalogue his Penzig Collection using research assistants—two of them were Taiwanese students—and library space, he was already engaging in the standardized labeling of new possessions and in offering privately purchased materials for public use.

Armed with new worldviews and with anamorphic visions, Taiwanese intellectuals in the Japanese period were bricoleurs in mixing transnational codes and cultural goods to their own advantages. This was especially true in the case of those overseas students in Tokyo between 1915 and 1935, who seemed to have no difficulty acquiring the Chinese and Japanese modernization experiences. Inspired by the revolution in China (1911) and the liberal spirit of the Taisho  era (1912–1925), Taiwanese students in Tokyo formed the Qifahui

era (1912–1925), Taiwanese students in Tokyo formed the Qifahui  (the Enlightenment Society) in 1918 and began to publish the first Chinese and Japanese bilingual monthly journal Tai oan chheng lian (Taiwan Youth) in 1920 when the society was renamed New People’s

(the Enlightenment Society) in 1918 and began to publish the first Chinese and Japanese bilingual monthly journal Tai oan chheng lian (Taiwan Youth) in 1920 when the society was renamed New People’s  . It has been often pointed out that Taiwan print culture began its modernization with this locally produced journal.24 However, our study suggests that modernization had taken root from as early as 1896, and that news media of the time already exhibited a transnational, anamorphic, and cosmopolitan (albeit discrepant or uneven) character.

. It has been often pointed out that Taiwan print culture began its modernization with this locally produced journal.24 However, our study suggests that modernization had taken root from as early as 1896, and that news media of the time already exhibited a transnational, anamorphic, and cosmopolitan (albeit discrepant or uneven) character.

NOTES

*An early version of this paper was presented at the Books in Number Conference, October 17–16, 2003, at Harvard University, in commemoration of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Harvard-Yenching Library. Yingche Huang of Aichi University, Japan, and Chengji Li of Tokyo University, Japan, contributed substantially to the arguments of this paper, to such an extent that they may well be considered coauthors. I would like to take the opportunity to thank them and to express my gratitude to the organizers and participants in the conference: James Cheng, Wilt Idema, Jessica Eykholt, Rudolph Wagner, and Patrick Hanan, among many others.

Epigraphs: Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library,” Selected Writings, 1927–1934 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999), 127.

Benedict Anderson, The Spectre of Comparisons: Nationalism, Southeast Asia, and the World (New York: Verso, 1998), 33.

1. Tanaka continued to add his own books to the Penzig Collection, making it difficult to tell what comprised the original acquisition. The number is given on the basis of the initial count. All references to the titles, publication data, and names (including Tanaa) are to the catalogue as compiled by National Taiwan University Library.

2. The collections are named either for the scholars who headed research projects on Taiwan aborigines (such as Inō) or in referrence to special collections of rare books originally owned by individuals (such as Ueta and U-shih-shan-fan).

3. See Huang Ying-che  , preface to

, preface to  [Remembering Taiwan], ed. Wu Mi-cha

[Remembering Taiwan], ed. Wu Mi-cha  et al., Tokyo University Press, 2005, 9–27; also, Li Cheng-chi

et al., Tokyo University Press, 2005, 9–27; also, Li Cheng-chi  ,

,

[The emergence of the reading public in 1930s Taiwan], 245–279.

[The emergence of the reading public in 1930s Taiwan], 245–279.

4. Wu Mingde  and Cai Pingli

and Cai Pingli  , eds., Guoli taiwan daxue tushuguan tian zhong wenku cangshu mulu

, eds., Guoli taiwan daxue tushuguan tian zhong wenku cangshu mulu  (Taipei: Guoli taiwan daxue tushuguan, 1998), 18.

(Taipei: Guoli taiwan daxue tushuguan, 1998), 18.

5. Wu Wenhsing  , Riju shidai Taiwan shifanjiaoyu zhi yanjiu

, Riju shidai Taiwan shifanjiaoyu zhi yanjiu  (Taipei: Guoli taiwan shifan daxue lishi yanjiusuo zhuankan, 1983), 12–13.

(Taipei: Guoli taiwan shifan daxue lishi yanjiusuo zhuankan, 1983), 12–13.

6. Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 4 (1938–1940), trans. Edmund Jephcott et al. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996–2003), 389.

7. Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, rev. ed. (New York: Verso, 1991), 36.

8. Yamamoto Taketoshi  , Jindai riben di xinwen duzheceng

, Jindai riben di xinwen duzheceng

(Tokyo: Fazheng daxue chubanshe, 1981), 180–181.

(Tokyo: Fazheng daxue chubanshe, 1981), 180–181.

9. Ishihara Kōsaku  , Taiwan Nichinichi sanshinian shi

, Taiwan Nichinichi sanshinian shi  (Taipei: Taiwan ririxin baoshe, 1928), 9.

(Taipei: Taiwan ririxin baoshe, 1928), 9.

10. Kawahara Isao  , “The State of the Taiwanese Culture and Taiwanese New Literature in 1937: Issues on Banning Chinese Newspaper Sections and Abolishing Chinese Writings,” in this volume.

, “The State of the Taiwanese Culture and Taiwanese New Literature in 1937: Issues on Banning Chinese Newspaper Sections and Abolishing Chinese Writings,” in this volume.

11. Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Norton, 1978), 89.

12. Lacan, Four Fundamental Concepts, 84.

13. Lacan, Four Fundamental Concepts, 82.

14. Lacan, Four Fundamental Concepts, 85.

15. See Tadao Yanaihara  , Shi nei yuan zhong xiong quanji

, Shi nei yuan zhong xiong quanji  , vol. 2 (Tokyo: Yanbo shudian, 1963), 196.

, vol. 2 (Tokyo: Yanbo shudian, 1963), 196.

16. Takekoshi Yosaburo  , Japanese Rule in Formosa (London: Longmans, 1907), 134.

, Japanese Rule in Formosa (London: Longmans, 1907), 134.

17. Hsu Hsueh-chi  et al., eds., Shui zhu ju zhuren riji

et al., eds., Shui zhu ju zhuren riji  , 6 vols. (Taipei: Academia Sinica, 2000–2002).

, 6 vols. (Taipei: Academia Sinica, 2000–2002).

18. Anderson, Spectre of Comparisons, 32–33.

19. Wu Wen-hsing  , Riju shidai taiwan jiaoyu zhi yanjiu

, Riju shidai taiwan jiaoyu zhi yanjiu

(Taipei: Guoli taiwan shifan daxue lishi yanjiusuo zhuankan, 1983).

(Taipei: Guoli taiwan shifan daxue lishi yanjiusuo zhuankan, 1983).

20. Huang Meier  , Ruzhi shiqi taipei diqu wenxue zuopin mulu

, Ruzhi shiqi taipei diqu wenxue zuopin mulu

(Taipei: Taipeishi wenxian weiyuanhui, 2003), 49–60.

(Taipei: Taipeishi wenxian weiyuanhui, 2003), 49–60.

21. Yang Bichuan  , Hou teng xin ping zhuan: taiwan xiandaihua dianjizhe

, Hou teng xin ping zhuan: taiwan xiandaihua dianjizhe

(Taipei: Yiqiao chubanshe, 1996).

(Taipei: Yiqiao chubanshe, 1996).

22. Anderson, Spectre of Comparisons, 33.

23. Anderson, Spectre of Comparisons, 33.

24. Wu Sanlian  , Cai Peihuo

, Cai Peihuo  , Ye Rongzhong

, Ye Rongzhong  , Chen Fengyuan

, Chen Fengyuan  , and Lin Boshou

, and Lin Boshou  , Taiwan minzu yundongshi

, Taiwan minzu yundongshi  (Taipei: Zili wanbao chubanshe, 1971).

(Taipei: Zili wanbao chubanshe, 1971).

(1885–1976), then professor in the agriculture division of Taipei Imperial University (the forerunner of the National Taiwan University, hereafter abbreviated as TIU). Tanaka had just been appointed the first university librarian (1929–1934) and was charged with starting to build the university’s collection. An eminent Japanese orchard horticulturalist, Tanaka came from a very wealthy family—his father, Tanaka Tashichirō

(1885–1976), then professor in the agriculture division of Taipei Imperial University (the forerunner of the National Taiwan University, hereafter abbreviated as TIU). Tanaka had just been appointed the first university librarian (1929–1934) and was charged with starting to build the university’s collection. An eminent Japanese orchard horticulturalist, Tanaka came from a very wealthy family—his father, Tanaka Tashichirō  , was the founder of Kobe Bank—and used US$100,000 of the inheritance from his father to purchase the Penzig Collection in 1930 (figs. 4.1 and 4.2).

, was the founder of Kobe Bank—and used US$100,000 of the inheritance from his father to purchase the Penzig Collection in 1930 (figs. 4.1 and 4.2). , Huart, U-shih-shan-fang

, Huart, U-shih-shan-fang  , Ueta

, Ueta  , Momoki

, Momoki  , and Nagasawa

, and Nagasawa  collections,

collections,

, the first minister of academic affairs under the Taiwan governor-general, and realized in July 1898, when the “Regulations concerning Taiwan public schools” were promulgated to familiarize the Taiwanese with the “national” Japanese language and culture, and when three systems of schooling were adopted—Japanese, Taiwanese, and aborigine—to reinforce racial differences.

, the first minister of academic affairs under the Taiwan governor-general, and realized in July 1898, when the “Regulations concerning Taiwan public schools” were promulgated to familiarize the Taiwanese with the “national” Japanese language and culture, and when three systems of schooling were adopted—Japanese, Taiwanese, and aborigine—to reinforce racial differences. became president and launched a “Taiwanization” movement that the collections, by then heavily deteriorated and in deplorable conditions, drew attention again. History thus plays another traitorous and naughty trick on the collector, making narration of the colonial and postcolonial histories increasingly difficult.

became president and launched a “Taiwanization” movement that the collections, by then heavily deteriorated and in deplorable conditions, drew attention again. History thus plays another traitorous and naughty trick on the collector, making narration of the colonial and postcolonial histories increasingly difficult. followed Koxinga

followed Koxinga  there. Shen and twelve other exiled literati formed a literary society called Dongyin

there. Shen and twelve other exiled literati formed a literary society called Dongyin  (Reciting in the East) and saw to the distribution of their poems. In fact, even before the Chinese immigrants and exiles came to the island, Dutch missionaries had introduced the aborigines to the Bible and provided a translation of the New Testament in one of the local languages. The style of printing indicates that the printers may have come from the Fukien province of southern China.

(Reciting in the East) and saw to the distribution of their poems. In fact, even before the Chinese immigrants and exiles came to the island, Dutch missionaries had introduced the aborigines to the Bible and provided a translation of the New Testament in one of the local languages. The style of printing indicates that the printers may have come from the Fukien province of southern China. (Taiwan News) was launched. One of its goals was to satisfy the needs of the Japanese in Taiwan who had developed newspaper-reading habits back in Japan. It also aimed to report important events as they occurred. The Meiji era is famous for its modernization project to “popularize” Western knowledge and national news.

(Taiwan News) was launched. One of its goals was to satisfy the needs of the Japanese in Taiwan who had developed newspaper-reading habits back in Japan. It also aimed to report important events as they occurred. The Meiji era is famous for its modernization project to “popularize” Western knowledge and national news. , between 1898 and 1900, Taiwan news paper and media culture underwent a second structural transformation by going public. As sanctioned by the governor-general, Kodama Gentar

, between 1898 and 1900, Taiwan news paper and media culture underwent a second structural transformation by going public. As sanctioned by the governor-general, Kodama Gentar , and civil officer Got

, and civil officer Got (1857–1929), the right to operate news papers was handed over to Japanese commoners in Taiwan, who collected capital and ran their businesses according to market logic. Public opinion was galvanized for the first time to criticize the colonial regime in Taiwan, and interest shifted to local issues in order to attract the attention of readers and consumers located in three cities—Taipei, Tainan, and later Taichung. From 1898 onward, local news papers in Japanese had a much wider circulation in Taiwan than in Japan (see

(1857–1929), the right to operate news papers was handed over to Japanese commoners in Taiwan, who collected capital and ran their businesses according to market logic. Public opinion was galvanized for the first time to criticize the colonial regime in Taiwan, and interest shifted to local issues in order to attract the attention of readers and consumers located in three cities—Taipei, Tainan, and later Taichung. From 1898 onward, local news papers in Japanese had a much wider circulation in Taiwan than in Japan (see

= One of three newspapers for Imperial use in Taiwan

= One of three newspapers for Imperial use in Taiwan = One of the nonofficial newspapers funded by the Japanese living in Taiwan

= One of the nonofficial newspapers funded by the Japanese living in Taiwan = One of the “yellow” newspapers in the 1930s (notorious for reporting on violence, murders, rapes)

= One of the “yellow” newspapers in the 1930s (notorious for reporting on violence, murders, rapes)

(Taiwan Daily News) on its side, countered by Tai oan chheng lian

(Taiwan Daily News) on its side, countered by Tai oan chheng lian  (Taiwan Youth, 1920) and Taiwan shin minp

(Taiwan Youth, 1920) and Taiwan shin minp

(Taiwan People’s News, 1923), which were introduced by Taiwanese intellectuals. However, a detailed analysis of the content of the newspapers and journals shows that ideology might not have been an important motivation. In early issues of the so-called official newspaper Taiwan nichinichi shinp

(Taiwan People’s News, 1923), which were introduced by Taiwanese intellectuals. However, a detailed analysis of the content of the newspapers and journals shows that ideology might not have been an important motivation. In early issues of the so-called official newspaper Taiwan nichinichi shinp

,

,  . “Even if covered up it still stinks; it just wont’t shup up.” “Try to cover it up with one more piece of paper.” [The paper is aptly entitled “peace and prosperity.”]

. “Even if covered up it still stinks; it just wont’t shup up.” “Try to cover it up with one more piece of paper.” [The paper is aptly entitled “peace and prosperity.”] , a town clerk at Fengyuan in Taichung county, show that he was a dedicated subscriber to and an avid reader of both the Taiwan nichinichi shinp

, a town clerk at Fengyuan in Taichung county, show that he was a dedicated subscriber to and an avid reader of both the Taiwan nichinichi shinp (Taiwan News) from as early as 1900.

(Taiwan News) from as early as 1900.

. Hud

. Hud .

. , Prime Minister Hara Kei

, Prime Minister Hara Kei  was finally able to appoint Den Kenjir

was finally able to appoint Den Kenjir (1919–1923) as Taiwan’s first civilian governor-general to bring into effect his reforms in the colony. Hara Kei’s rise to power greatly depended on using Taiwanese news media to expose corruption and violence in the colony.

(1919–1923) as Taiwan’s first civilian governor-general to bring into effect his reforms in the colony. Hara Kei’s rise to power greatly depended on using Taiwanese news media to expose corruption and violence in the colony. era (1912–1925), Taiwanese students in Tokyo formed the Qifahui

era (1912–1925), Taiwanese students in Tokyo formed the Qifahui  (the Enlightenment Society) in 1918 and began to publish the first Chinese and Japanese bilingual monthly journal Tai oan chheng lian (Taiwan Youth) in 1920 when the society was renamed New People’s

(the Enlightenment Society) in 1918 and began to publish the first Chinese and Japanese bilingual monthly journal Tai oan chheng lian (Taiwan Youth) in 1920 when the society was renamed New People’s  . It has been often pointed out that Taiwan print culture began its modernization with this locally produced journal.

. It has been often pointed out that Taiwan print culture began its modernization with this locally produced journal. , preface to

, preface to  [Remembering Taiwan], ed. Wu Mi-cha

[Remembering Taiwan], ed. Wu Mi-cha  et al., Tokyo University Press, 2005, 9–27; also, Li Cheng-chi

et al., Tokyo University Press, 2005, 9–27; also, Li Cheng-chi  ,

,

[The emergence of the reading public in 1930s Taiwan], 245–279.

[The emergence of the reading public in 1930s Taiwan], 245–279. and Cai Pingli

and Cai Pingli  , eds., Guoli taiwan daxue tushuguan tian zhong wenku cangshu mulu

, eds., Guoli taiwan daxue tushuguan tian zhong wenku cangshu mulu  (Taipei: Guoli taiwan daxue tushuguan, 1998), 18.

(Taipei: Guoli taiwan daxue tushuguan, 1998), 18. , Riju shidai Taiwan shifanjiaoyu zhi yanjiu

, Riju shidai Taiwan shifanjiaoyu zhi yanjiu  (Taipei: Guoli taiwan shifan daxue lishi yanjiusuo zhuankan, 1983), 12–13.

(Taipei: Guoli taiwan shifan daxue lishi yanjiusuo zhuankan, 1983), 12–13. , Jindai riben di xinwen duzheceng

, Jindai riben di xinwen duzheceng

(Tokyo: Fazheng daxue chubanshe, 1981), 180–181.

(Tokyo: Fazheng daxue chubanshe, 1981), 180–181. , Taiwan Nichinichi sanshinian shi

, Taiwan Nichinichi sanshinian shi  (Taipei: Taiwan ririxin baoshe, 1928), 9.

(Taipei: Taiwan ririxin baoshe, 1928), 9. , “The State of the Taiwanese Culture and Taiwanese New Literature in 1937: Issues on Banning Chinese Newspaper Sections and Abolishing Chinese Writings,” in this volume.

, “The State of the Taiwanese Culture and Taiwanese New Literature in 1937: Issues on Banning Chinese Newspaper Sections and Abolishing Chinese Writings,” in this volume. , Shi nei yuan zhong xiong quanji

, Shi nei yuan zhong xiong quanji  , vol. 2 (Tokyo: Yanbo shudian, 1963), 196.

, vol. 2 (Tokyo: Yanbo shudian, 1963), 196. , Japanese Rule in Formosa (London: Longmans, 1907), 134.

, Japanese Rule in Formosa (London: Longmans, 1907), 134. et al., eds., Shui zhu ju zhuren riji

et al., eds., Shui zhu ju zhuren riji  , 6 vols. (Taipei: Academia Sinica, 2000–2002).

, 6 vols. (Taipei: Academia Sinica, 2000–2002). , Riju shidai taiwan jiaoyu zhi yanjiu

, Riju shidai taiwan jiaoyu zhi yanjiu

(Taipei: Guoli taiwan shifan daxue lishi yanjiusuo zhuankan, 1983).

(Taipei: Guoli taiwan shifan daxue lishi yanjiusuo zhuankan, 1983). , Ruzhi shiqi taipei diqu wenxue zuopin mulu

, Ruzhi shiqi taipei diqu wenxue zuopin mulu

(Taipei: Taipeishi wenxian weiyuanhui, 2003), 49–60.

(Taipei: Taipeishi wenxian weiyuanhui, 2003), 49–60. , Hou teng xin ping zhuan: taiwan xiandaihua dianjizhe

, Hou teng xin ping zhuan: taiwan xiandaihua dianjizhe

(Taipei: Yiqiao chubanshe, 1996).

(Taipei: Yiqiao chubanshe, 1996). , Cai Peihuo

, Cai Peihuo  , Ye Rongzhong

, Ye Rongzhong  , Chen Fengyuan

, Chen Fengyuan  , Taiwan minzu yundongshi

, Taiwan minzu yundongshi  (Taipei: Zili wanbao chubanshe, 1971).

(Taipei: Zili wanbao chubanshe, 1971).