Incident of 1915

Incident of 1915HEGEMONY AND IDENTITY IN THE COLONIAL EXPERIENCE OF TAIWAN, 1895–1945

Prior to the 1990s, the story of colonial Taiwan under Japanese rule was rarely heard in the English-speaking world; it also lacked an audience in Taiwan itself. With its democratization, which also removed pan-Chinese ideology, people on the island began to show interest in their own history. A space was thus created in which colonial experience could be researched and its stories told. However, since the time for intensive research has been relatively short thus far, the stories of both the colonizer and the colonized, particularly in regard to cultural domains, remain rudimentary, and not entirely precise in many details. At best, it may be more like an outline than a narrative; it may be a study based on two organizing concepts, hegemony on the colonizer’s side and identity on the side of the colonized.

After a short discussion of the template—hegemony and identity—in terms of which the stories will be told, my essay will focus on the discourses of both colonizers and colonized in three specific periods, the 1910s, the 1920s and 1931–1945. The three periods roughly correspond to the three stages of the colonial viceroy-ship, in which the military viceroys dominated the first and the third stages, and the civilian the second period. Because of these shifts in power base, either from the military to bureaucracy or vice versa, we also witness the shifts of the source of coercion from soldiers to the police and then back to the soldiers and hence the shift of social atmosphere from tension to relaxation and back to tension. This rhythm also affected the spaces in which cultural activities, including discourses of ideologies, could be initiated.

By focusing on discourses from both sides of colonialism, we raise the issue of how the Japanese colonizers achieved a “weak hegemony” by polarizing the Taiwanese into two types and ascribing onto them different memberships—a traditional Chinese identity for the masses and a “modern” identity for the elites. (Compared with the Japanese, the Taiwanese elites were tacitly recognized as second-class though almost as equally modern.)

THE SCHEME OF HEGEMONY AND COUNTERHEGEMONY

“The intellectuals,” Antonio Gramsci suggests (1971:12), “are the dominant group’s ‘deputies’ exercising the subaltern functions of social hegemony and political government.” He refers to the indoctrinating and coercive work done by fellow Italian intellectuals of rural background. Gramsci highlights the intellectuals’ role in the noncoercive state influence in civil society in terms of “moral leadership” or “social hegemony”; however, such a role worked to support the hegemonic regime in a colonial context where the Japanese ruled over the Han-Taiwanese. Gramsci’s notion of hegemony serves as an ideal starting point for us to tackle the identity problem of the Taiwanese under Japanese rule. But first we need to elaborate it with the help of other notions, such as counterhegemony (Williams 1980), narrative (Ricoeur 1992 and White 1987), and a typology of compliance (Etzioni 1975).

Hegemony, as Gramsci (1971:334) views it, denotes an intellectual unity theory and practice. For an intellectual to support the state’s noncoercive hegemonic control what she says must be consistent both with what the rulers intended and with what the ruled actually felt. Her consistent discourse, especially when put in a narrative form, then amounts to a constant patchwork that gauges and reflects developments in state-society relations. Here Etzioni’s “exhaustive” classification of power and compliance is helpful; for he asserts that the rulers always have coercive, remunerative, and normative powers in stock and the ruled have the choice of alienative, calculative, or moral compliance in response. Not only does he thus unintentionally capture a nuance of hegemony by specifying both the practice (coercion and normalization) and the response (alienation and moralization) of the two dimensions of power, but he also adds the power of remuneration, or simply bribery in a power relation, which is certainly a time-honored tactic to induce popular compliance (Lukes 1974). But in order to render the Japanese rule and the Taiwanese submission intelligible, we must examine the constituents of both “normative” power and “moral” compliance. It is at this juncture that the notion of narrative discourse becomes helpful.

In a colonial context, the ruling regime, with the help of intellectuals, “talks” the colonized into compliance by weaving stories about them. These stories sanction the colonized both negatively, by describing how rebels will be punished, and positively, by exhorting the merits of being loyal colonial subjects. The stories can of course always be told with a mixture of coercive and remunerative powers available to the regime. They can on their own be effective only by inducing compliance. Their effectiveness is due to two mechanisms specified by Ricoeur and White.

For Ricoeur (1992), the mechanism of narrative identity functions in the context of story communication. In that context, every listener comes to the story with her distinctive personality traits and life commitments, all molded by dominant social values. The same set of values is represented first in the characters and in their personal involvement in the events that make up “episodes.” When a storyteller edits the episodes into a causal sequence, a “causal employment” (Somers 1994:616), she contrives a story to be told. Social values are often the criteria for turning episodes into plots and stories. The value-molded listener can thus identify herself with the character tailored by the story in accord with the same set of values. This moment of identification is the moment of coming to pass of a narrative identity with which she grows and thus changes her perception of her “real” self.

For White (1980), it is the mechanism of a secondary referent that makes a reader recognize the figurative truths of a narrative, whether in fiction or in history. Every narrative possesses a primary referent that is the literal reflection of the objective world; it gives the reader a sense of realism. But the story also provides a secondary referent, which, parallel to Ricoeur’s expanding units of episode, plot, and story, is made of motifs, themes, and plot structure. It is the secondary referent that induces emotional and attitudinal changes in the reader by sending her to the allegorical world immanent in the story. White wisely comments that the effectiveness of the secondary referent depends on the repertoire of literary genres available in a culture. A secondary referent embedded in an alien genre may thus suffer from a lack of familiarity among its readers and thus a diminishment of its persuasiveness.

With the mechanisms of the narrative identity and the secondary referent, a hegemon’s stories about its subjects are arguably capable of entrapping the latter’s loyalty, provided that the subjects do not possess either “residual” or “emergent” culture that can tell them alternative stories. These two types of counterhegemonic culture signify, for Williams (1977), resources for the subjects to imagine stories about themselves (also with the help of the notions of narrative identity and secondary referent) other than what the hegemon imposes upon them by means of education or mass media. Tradition and conventions constitute the residual resources that have always been ingredients of the subjects’ lifestyle and that the hegemon seeks to transform, if not destroy. Emergent resources, on the other hand, lie in the future when industrialization gives rise to a working class that is conscious of both resisting and altering the industrial status quo. The two countercultures thus situate the subjects, including the colonized, in a temporal sequence—they have at their disposal cultural resources either from past or from future to fight back their hegemon’s attempts at indoctrination. In that sense, a ruler’s hegemonic control is never complete; as we have mentioned, it is a patchwork that requires constant attention to countercultures in order to outwit them.

This scheme of hegemony and counterhegemony therefore focuses on the stories of the identities of the colonized. On the one hand, the colonizers construct the narratives of their subjects by means of narrative identity and secondary referent. Their purpose is to induce the subjects’ moral compliance. But when the normative attempt fails, they can always switch back to coercion or bribery for remedy. On the other hand, facing growing hegemonic pressures, the colonized still have the residual and/or the emergent symbolic resources with them. Their posture may be on the whole resistant but they appear to be most vulnerable when the old type of resource is dwindling but the new type is not forthcoming. This is the juncture where “weak hegemony,” a situation where a portion of the colonized is brainwashed into loyal subjects, comes to existence, as we shall describe in what follows.

THE THREE PHASES OF THE TAIWANESE COLONIAL STORY

The Seiraian  Incident of 1915

Incident of 1915

As the Taiwan government-general (sōtokufu  ) celebrated its twenty-year rod-of-iron rule on June 17, 1915, with a “custom improvement movement,”1 the largest millenarian rebellion the Japanese had ever seen in Taiwan erupted to chill their celebratory mood. Its participants, mostly illiterate peasants, were drawn to a surrogate “godly master” (shenzhu

) celebrated its twenty-year rod-of-iron rule on June 17, 1915, with a “custom improvement movement,”1 the largest millenarian rebellion the Japanese had ever seen in Taiwan erupted to chill their celebratory mood. Its participants, mostly illiterate peasants, were drawn to a surrogate “godly master” (shenzhu  ), called Yu Qingfang

), called Yu Qingfang  , who promised to build a “state of immense brightness and benevolence” (daming cibei guo

, who promised to build a “state of immense brightness and benevolence” (daming cibei guo  ) here and now, and because it was “pre-political” (Hobsbawm 1959:57–59), with the leader stratum being extremely vague about how to bring the chiliastic state to pass, let alone any articulation of the relationship between the godly state and the nation-states in the rest of the world. The Japanese government, on its part, treated the rebellion as but another incident of banditry, although of a significant magnitude, and believed its superstitious participants deserved nothing short of hanging. The official discourse on colonized banditry was well set before the incident.

) here and now, and because it was “pre-political” (Hobsbawm 1959:57–59), with the leader stratum being extremely vague about how to bring the chiliastic state to pass, let alone any articulation of the relationship between the godly state and the nation-states in the rest of the world. The Japanese government, on its part, treated the rebellion as but another incident of banditry, although of a significant magnitude, and believed its superstitious participants deserved nothing short of hanging. The official discourse on colonized banditry was well set before the incident.

The notion of banditry presupposes an interruption of the established social order of whatever nature. It implies more than a nuisance from the ruler’s point of view; it implies an undesirable reading of the colonized that, without distinction, should be eliminated. “Bandit” was a term invented under the colonial context, as a famous historian of contemporary police affairs, Washizu Atsushiya

, candidly admitted: “The so-called bandit, or local villain, was not used in traditional Taiwan. It gained currency after Taiwan was ceded to Japan” (TSKE 1938, 2:267).

, candidly admitted: “The so-called bandit, or local villain, was not used in traditional Taiwan. It gained currency after Taiwan was ceded to Japan” (TSKE 1938, 2:267).

After “bandit” came into vogue, the officials used it to designate three types of rebels: Qing soldiers who stayed in Taiwan after 1895 and who were committed to toppling the Japanese colonial government, indigenous gangsters who controlled fixed turfs, and common-folks-turned-rebels whose family members were mistakenly killed by the Japanese military or who themselves were maliciously accused of being bandits.2 Washizu wasted no time in pointing out that the government could apply means of redress most effectively to the last group. The exact number of “bandits” was not available, but from the 8,258 cases of banditry reported to police stations in the period 1897–1900, Washizu estimated that, by 1903, the Japanese had killed or arrested well over ten thousand bandits on the island of some three million Han-Taiwanese (TSKE 1938, 2:268–269). This official classification of “bandits” (to be lumped together as “patriots” after the 1945 change of regime) met the sōtokufu’s control expediency. The government coined the publicly degrading term “bandit” for the Taiwanese to use in refer to their rebellious compatriots. The term pressured the majority of the Taiwanese, by focusing punishment on the “bandit” groups, to do what the colonizers desired, and it divided its potential threat onto the three groups that could be subjected to different counterstrategies.3

Why were there so many rebellions in Taiwan not only under Japanese rule but also in the earlier Qing period (1644–1911)?4 Implicitly comparing it to the unbroken Japanese emperorship,5 Washizu specifically pointed out the notion of “replaceable emperorship” (TSKE 1938, 2:265; 1939, 3:3), which, as a few contemporary Japanese colonizers asserted, was based on the Chinese cosmo-political view of the “mandate of heaven.” According to this view, an emperor would be dethroned if he did not follow heaven’s will by being “virtuous” (Shibata 1923:208). His loss of virtue was best indicated by his subjects’ complaints. A virtuous person, of whatever social level, would be mandated by heaven to lead the disgruntled people to oust the old emperor. This essentially Confucian political view became a folk belief with a twist—not only would heaven protect the people who followed the virtuous leader with his godly soldiers, but the people themselves would also become such soldiers by drinking holy water or by carrying paper charms (shenfu  ; Shibata 1923:211–216; Igeda 1981:196). This notion of “heavenly generals and godly soldiers” (tianjiang shenbing

; Shibata 1923:211–216; Igeda 1981:196). This notion of “heavenly generals and godly soldiers” (tianjiang shenbing  ) loomed large in the Seiraian incident and was the core element of its millenarianism.

) loomed large in the Seiraian incident and was the core element of its millenarianism.

In the colonial context, rebels who believed in the heavenly mandate had spiritually sinned against the irreplaceable Japanese emperor, and their treasonous behavior could be redeemed only by the death penalty. In 1898 Viceroy Kodama Gentarō  proclaimed an extremely harsh order for punishing bandits, with the first article reading:

proclaimed an extremely harsh order for punishing bandits, with the first article reading:

Those bandits who gather themselves to coerce or threaten others, no matter what their purposes are, are subject to punishment according to the following criteria:

1. The leaders and instigators are sentenced to death.

2. Those who participate in the decision-making or commanding are sentenced to death.

3. The mere participants or those who provide services are subject to imprisonment for a definite term and to harsh corvée. (TSKE 1938, 2:282)

By the time of the Seiraian incident in 1915, the sōtokufu had already defined who the rebels were, why they were motivated, and how they were to be treated by the government. The last and the largest pre-modern millenarial violence in Taiwan was to be framed by the mundane bureaucratic discourse on banditry, a discourse couched heavily on the coercive power at the sōtokufu’s disposal.

What, however, did the Seiraian rebels think of themselves? The answer could not be as “bandits,” and the question could not be answered directly. It is from their religion and its morality books (shanshu  ) that we might hope to look into their moral universe. The stories in these books can tell us both the narrative identities as imagined in the rebels’ reading (or more precisely, listening, since most of them were illiterate peasants), and the secondary referents that set the tone for their emotions and attitudes. These morality books may be divided into two parts: wartime literature used by leaders such as Yu Qingfang to agitate their believers, and a peacetime narrative that was preached as a daily routine. Nonetheless, stories in both parts focused on the need for the male believers fearing Buddhist-type retribution (baoying

) that we might hope to look into their moral universe. The stories in these books can tell us both the narrative identities as imagined in the rebels’ reading (or more precisely, listening, since most of them were illiterate peasants), and the secondary referents that set the tone for their emotions and attitudes. These morality books may be divided into two parts: wartime literature used by leaders such as Yu Qingfang to agitate their believers, and a peacetime narrative that was preached as a daily routine. Nonetheless, stories in both parts focused on the need for the male believers fearing Buddhist-type retribution (baoying  ), to respect both gods and parents, and to avoid at all costs greed and lust.

), to respect both gods and parents, and to avoid at all costs greed and lust.

In his wartime literature, Yu Qingfang declares war against Japanese (Chen 1977:149):

Now it is May of 1915. Japanese thieves have been in Taiwan for two decades and their rulership has come to an end.… Our State of Immense Brightness and Benevolence has just been set up. I, the Marshal, have received the heavenly mandate to fight with the thieves.… Wherever our heavenly soldiers go, the enemies will surrender.

Before this declaration, the morality books of the Seiraian Temple, the stronghold of the rebels, had prepared the believers to accept a coming Second Advent. One such morality book, The Book of Five Masters, described the coming calamity: “The heaven and earth are immensely dark … humans are beheaded and ghosts’ feet are cut off. There is no justice; there is no hierarchy” (Anonymous 1862:5). Behind this picture of living hell was the traditional Buddhist notion of retribution: “If you sow this melon seed, you inevitably get this melon,” a famous Buddhist allegory explains. The living hell was to be caused by nonbelievers, especially by Japanese: “You the commoners should behave yourselves, otherwise evils will fall upon you. Do not obtain unjust wealth, lest your descendants should not live long. Respect the gods and parents, and you should prosper” (Anonymous 1862:5). In Seiraian’s wartime literature, what was to have been learned were the moral teachings that believers should have absorbed—be careful with money and respect both gods and parents. However, it was in peacetime morality books that believers were to be gendered: in addition to prudence and respect, male converts should abstain from lust.

The only book written by Seiraian priests, with Yu Qingfang as a coauthor, The Book of the Alert Heart (Jingxinpian  ), tells two stories. One is about a rich man who married a widow by force and forsook her son. His wealth was exhausted in two years due to thefts and fire and he thus died of anxiety. The son, on the other hand, did well and married a merchant’s daughter. Later, he married a concubine who happened to be a former concubine of his stepfather. The other story is about two sisters-in-law who spoke ill of the other brother to each other’s husband. They caused the two brothers to divide their family properties. The morals of the stories are clearly encapsulated in the Seiraian morality books: “Sons who do not pay their parents piety will be struck to death by thunder, and who are addictive to lust … will be imposed upon disasters from heaven. Proper and just behavior is a must and one should respect all agnate and cognate hierarchies” (Anonymous 7).

), tells two stories. One is about a rich man who married a widow by force and forsook her son. His wealth was exhausted in two years due to thefts and fire and he thus died of anxiety. The son, on the other hand, did well and married a merchant’s daughter. Later, he married a concubine who happened to be a former concubine of his stepfather. The other story is about two sisters-in-law who spoke ill of the other brother to each other’s husband. They caused the two brothers to divide their family properties. The morals of the stories are clearly encapsulated in the Seiraian morality books: “Sons who do not pay their parents piety will be struck to death by thunder, and who are addictive to lust … will be imposed upon disasters from heaven. Proper and just behavior is a must and one should respect all agnate and cognate hierarchies” (Anonymous 7).

From both wartime and peacetime Seiraian literature, therefore, there emerged an ideal model, a gentleman who believed in the Buddhist teaching of retribution and who thus respected both gods and parents, abstained from womanizing, and earned a just income. This narrative identity was the goal striven for by Seiraian believers lest they, as indicated by the secondary referent in the stories, should be exposed to violent death in living hell. In their imaginations, they were not bandits with superstitious beliefs in heavenly generals and godly soldiers, as the Japanese colonizers would have imagined.

In regard to the underclass of Han-Taiwanese involved in the Seiraian incident, the identity stories from themselves and from the colonizers simply crossed each other. This also indicated that, except by resorting to coercion, twenty years after their occupation of Taiwan Japanese were still far away from hegemonizing the moral universe of the Han-Taiwanese who came from a lower-class background.

The Discourses of Assimilation and Nationalism in the 1920s

The 1920s were a transitional period in the social history of Taiwan. Epidemics no longer threatened. Malaria had been effectively controlled. Physicians trained in Western medicine outnumbered Chinese herbal doctors. Even rinderpest had been eliminated.… Education had become popular. Conservative peasants also actively adopted new species and new technology. Productivity increased. Mobility of the population also increased. Bicycles, cars, and trucks became popular. Life had thus been improved. [Modern social movements occurred precisely at this juncture.]

(Chen Shaoxin 1979:127)6

With these words, Chen Shaoxin  , a Taiwanese sociologist trained during the colonial period (1906–1966), described a society just entering on the threshold of modernity, which was being imposed by a colonial regime.7 It is against this technology-based background that we should probe the contrasting discourses between assimilationism on the rulers’ side and the nationalist ideology of Taiwanese modern social movements on the side of the ruled. Under the colonizers’ modernizing and assimilating assault, the nationalism that Taiwanese intellectuals had learned from their Japanese professors was fundamentally ambiguous. It referred to a nationalist “I” that could be Taiwanese, or Chinese, or Japanese, or all of them. In other words, this nationalist discourse indicated the beginning of hegemonic control, especially of Taiwanese intellectuals.

, a Taiwanese sociologist trained during the colonial period (1906–1966), described a society just entering on the threshold of modernity, which was being imposed by a colonial regime.7 It is against this technology-based background that we should probe the contrasting discourses between assimilationism on the rulers’ side and the nationalist ideology of Taiwanese modern social movements on the side of the ruled. Under the colonizers’ modernizing and assimilating assault, the nationalism that Taiwanese intellectuals had learned from their Japanese professors was fundamentally ambiguous. It referred to a nationalist “I” that could be Taiwanese, or Chinese, or Japanese, or all of them. In other words, this nationalist discourse indicated the beginning of hegemonic control, especially of Taiwanese intellectuals.

Out of the public discourses on assimilationism in the early 1920s, Taiwan dōkasaku ron (On the assimilative policy in Taiwan  ) by Shibata Sunao

) by Shibata Sunao  (1923)8 probably stood out as the most systematic and articulate account of the new 1920 policy of “gradual assimilation.”9 Together with Nakanishi

(1923)8 probably stood out as the most systematic and articulate account of the new 1920 policy of “gradual assimilation.”9 Together with Nakanishi  ’s Dōkaron (On assimilation

’s Dōkaron (On assimilation  , 1914),10 the two texts set the tone and themes that would resonate among the Japanese assimilationists throughout the 1920s.

, 1914),10 the two texts set the tone and themes that would resonate among the Japanese assimilationists throughout the 1920s.

Assimilation as a policy, Shibata contended, was to be framed in cultural terms. It aimed to bring the Taiwanese “national ethos,” or simply nationality, in line with its Japanese counterpart—which he, incidentally, never specified in the text. This cultural policy required a long time to become effective and, when it did, it would show in changes of “social phenomena” in Taiwan (1923:6–8). After almost three decades of Japanese rule, Taiwan society had reached a “humdrum” moment (53) of boredom caused by tensions between constant and variable thoughts that together comprised the configuration of the Taiwanese nationality. The variable thoughts informed by reason and knowledge had been “rationalized” (26) by an advanced culture, Japan, in an effort to improve the socioeconomic infrastructure of Taiwan over the previous three decades. Thus the rationalizing process disconnected the variable thoughts from the constant thoughts, which remained centered on the “heavenly mandate” and “ancestry worship” (30–40). Out of this discord between the rational and the traditional sprang the general Taiwanese public boredom; they were ready for a movement of enlightenment:11

When the constant thoughts, which serve as the guidance of national spirit, cannot accord with the variable thoughts … which respond to environmental stimulus, this is a time when people wake up from their past life and feel puzzled about leading their future life. In cultural history, this is called a time of enlightenment. (Shibata 1923:53)

For Shibata, these constant thoughts could serve as a buffer against the “radical thoughts” of socialism and anarchism in the name of “enlightenment” (65). But assimilation would, in the long run, erode these traditional thoughts.

He thus suggested that the government should heed three fundamental policies in order to promote assimilation. Regarding religion, if the governmental authority was to change its hitherto free-handed policy, it should avoid encroaching on the functions Taiwanese folk beliefs, or what Shibata calls “imperial pantheism,” had performed—a highly tolerant attitude toward other religions, a substitute for an set of ethical criteria for good and evil, and the only entertainment for the rank and file (75–81). In education, the authority should promote the study of Confucianism and Chinese learning, for—contrary to his predecessor, Nakanishi—Shibata insisted that the ideals of Confucianism had been incorporated into the Japanese “national essence” (kokutai  ) and that their promotion would contribute to assimilation (82–66)—a point to which I shall return shortly. Finally, in social education, he suggested that a new office should be created in the government-general to coordinate the efforts of several civilian associations to change old customs (mainly queue-wearing and foot-binding) and to promote the learning of the Japanese language (98–102).

) and that their promotion would contribute to assimilation (82–66)—a point to which I shall return shortly. Finally, in social education, he suggested that a new office should be created in the government-general to coordinate the efforts of several civilian associations to change old customs (mainly queue-wearing and foot-binding) and to promote the learning of the Japanese language (98–102).

The overall tone of this scheme was, as Shibata himself admitted (61), “conservative.” In fact, other than the creation of an office of social education, he was suggesting that the colonial government refrain from interfering in either religion or education. He seemed to be optimistic about the inevitable coming of assimilation over the long run. This optimism in part arose from Shibata’s eccentric view of the congruent national ethos of the Japanese and Chinese peoples, as can be seen in the following comparison.

If we turn to the relationship between Shibata and Nakanishi’s books, we immediately notice their opposing interpretation of the connection between “national essence” and assimilation in the famous “Rescript on Education,” always the supreme official source for justifying the assimilative policy.

Nakanishi’s 1914 text distinguished two main categories in the rescript. One was about “universal ethics”: filial piety, affection, harmony, truthfulness, modesty, and benevolence (2). These were essentially what traditional Confucian scholars in both China and Japan would subsume under the term “the five virtuous categories” (gorin  ), with the single omission of loyalty from the 1914 text. The other category concerned the special national essence of Japan: the loyalty of the subjects for “the prosperity of our Imperial Throne coeval with heaven and earth” (2, 30):12 “As [the rescript describes,] our empire was founded on a broad and everlasting basis … and our people united in loyalty and filial piety …, these are unique in Japan and can be seen nowhere else. These are therefore called Japan’s kokutai” (Nakanishi 1914:2). Hence the national ethos of the Japanese people: “be loyal to the Emperor and be patriotic to the state” (chūkun aikoku

), with the single omission of loyalty from the 1914 text. The other category concerned the special national essence of Japan: the loyalty of the subjects for “the prosperity of our Imperial Throne coeval with heaven and earth” (2, 30):12 “As [the rescript describes,] our empire was founded on a broad and everlasting basis … and our people united in loyalty and filial piety …, these are unique in Japan and can be seen nowhere else. These are therefore called Japan’s kokutai” (Nakanishi 1914:2). Hence the national ethos of the Japanese people: “be loyal to the Emperor and be patriotic to the state” (chūkun aikoku

), with the catch that the Emperor was the state (5). Thus, for Nakanishi, to assimilate the Taiwanese required the transplantation into their consciousness of the Japanese ethos of chūkun aikoku.

), with the catch that the Emperor was the state (5). Thus, for Nakanishi, to assimilate the Taiwanese required the transplantation into their consciousness of the Japanese ethos of chūkun aikoku.

But for Shibata, it was precisely the Confucian gorin, what Nakanishi called “the universal ethics,” that could help achieve a viable assimilative policy (1923:85). Shibata claimed that the Chinese were culturally distinguished from the Japanese by the former’s collective notions of heavenly mandate and ancestry worship, and the only way to influence these constant thoughts was by gradually rationalizing variable thoughts of mundane life until the Chinese self-consciously changed their fundamental ideas. With this concern, Shibata could only see gorin as a godsend, an extra help that might speed the assimilative process, but the important thing was to continue the rationalizing policies in the socioeconomic domains while keeping Taiwanese religion, education, and socialization intact.

In retrospect, the importance of Shibata’s work lies not so much in his offering guidance for policy-making, although an office of social education (shakaika  ) at the sōtokufu level was established in 1926 (Ajiken 1973:227), as in his systemizing Japanese themes of assimilation in the period after Nakanishi’s pioneering work and in directing discussion thereafter. Hence, in terms of the importance of education, Shibata redirected the focus on equal educational opportunities for both Japanese and Taiwanese students (TY 1.1 [1920]: 16; 2.1 [1921]: 20; 3.4 [1921]: 27) to respect for Confucian learning. He thus foreshadowed what Yanaihara, a famous Japanese scholar of imperialism, would later attack as Japan’s capitalistic substitution of the premodern Confucian schools, shobō

) at the sōtokufu level was established in 1926 (Ajiken 1973:227), as in his systemizing Japanese themes of assimilation in the period after Nakanishi’s pioneering work and in directing discussion thereafter. Hence, in terms of the importance of education, Shibata redirected the focus on equal educational opportunities for both Japanese and Taiwanese students (TY 1.1 [1920]: 16; 2.1 [1921]: 20; 3.4 [1921]: 27) to respect for Confucian learning. He thus foreshadowed what Yanaihara, a famous Japanese scholar of imperialism, would later attack as Japan’s capitalistic substitution of the premodern Confucian schools, shobō  (1984:148–151). In respect to religion, he contrasted what Yamoto (TY 2.5 [1921]: 28–31; 3.1 [1921]:15–20) proposed in basing colonial domination on Buddhism and asked that the functions of Taiwanese folk beliefs be taken seriously. Finally, regarding nationality, he clarified the previously vague discussions of the differences in national ethos (TY 1.1 [1920]: 27; 2.1 [1921]: 21–22; 3.4 [1921]: 21–33) and talked instead about “constant thoughts,” ideas which would later be echoed in, for example, Ihara’s elaboration of the Japanese nationality—chūkunaikoku and, incidentally, in ancestry worship (1926:222–249).

(1984:148–151). In respect to religion, he contrasted what Yamoto (TY 2.5 [1921]: 28–31; 3.1 [1921]:15–20) proposed in basing colonial domination on Buddhism and asked that the functions of Taiwanese folk beliefs be taken seriously. Finally, regarding nationality, he clarified the previously vague discussions of the differences in national ethos (TY 1.1 [1920]: 27; 2.1 [1921]: 21–22; 3.4 [1921]: 21–33) and talked instead about “constant thoughts,” ideas which would later be echoed in, for example, Ihara’s elaboration of the Japanese nationality—chūkunaikoku and, incidentally, in ancestry worship (1926:222–249).

Therefore, in the Japanese discourse on assimilationism, there emerged a prototheory and practice. The theory dictated that the national essence of the Taiwanese could be assimilated into the Japanese chūkunaikoku only by long-term socioeconomic policies that rationalized first the form and then, very gradually, the content of Taiwanese culture. In practice, the dominant assimilative discourse suggested a restrained attitude toward upsetting the cultural life of the Taiwanese in the domains of religion, education, and social education.

Turning now to the indigenous nationalism on the Taiwanese’ side, Dr. Jiang Weishui  (1891–1931), a Japanese-trained physician who founded both the Taiwan Cultural Society (1921) and later, the Taiwan Populist Party (1927), stood out as a middle-of-the-road advocate.13 Together with his long-term comrade, Xie Chunmu

(1891–1931), a Japanese-trained physician who founded both the Taiwan Cultural Society (1921) and later, the Taiwan Populist Party (1927), stood out as a middle-of-the-road advocate.13 Together with his long-term comrade, Xie Chunmu  (1902–1969), and his comrade-turned-foe, Cai Peihuo

(1902–1969), and his comrade-turned-foe, Cai Peihuo

(1889–1983), he shared a discourse of nationalism that was not only willing to compromise but fundamentally ambiguous. When Jiang became determined to set up the Populist Party, he had to convince the Japanese authorities that his party would serve as “a medium to promote good will between Japan and China.” His justification was as follows:

(1889–1983), he shared a discourse of nationalism that was not only willing to compromise but fundamentally ambiguous. When Jiang became determined to set up the Populist Party, he had to convince the Japanese authorities that his party would serve as “a medium to promote good will between Japan and China.” His justification was as follows:

Eighty percent of the Taiwanese came from Fujian [ ] and twenty percent from Guangdong [

] and twenty percent from Guangdong [ ]. The aborigines of these two provinces were assimilated into Chinese culture in the Han Dynasty [202 B.C.–A.D. 220]. This was also the era when Japan imported culture from China.… [Therefore] the three groups of aborigines had certainly married with the Han people and absorbed the latter’s culture. (Jiang 1998:127)

]. The aborigines of these two provinces were assimilated into Chinese culture in the Han Dynasty [202 B.C.–A.D. 220]. This was also the era when Japan imported culture from China.… [Therefore] the three groups of aborigines had certainly married with the Han people and absorbed the latter’s culture. (Jiang 1998:127)

Since the people of Fujian and Guangdong had been incorporated into China, their descendants in Taiwan understood Chinese better than the Japanese did and could work to improve Sino-Japanese relationships. Note that in this justification, it was the people of Fujian and the people of Guangdong who were the real ancestors of the Taiwanese and who could therefore be distinguished from the Han people. Written in early 1927, the tone of this piece is different from that of Jiang’s earlier text of 1924. There he defined “people,” or more precisely “nation,” as “an anthropological fact”: “no matter how the Taiwanese changed into Japanese citizens, they did not thereby become members of the Japanese nation. It cannot be denied as fact that the Taiwanese are Chinese, belonging to the Han people” (Jiang 1998:27). When talking about being a medium between China and Japan, his justification in 1924 was that because the “Taiwanese have both Chinese origins and Japanese citizenship,” they can naturally play the role well (1998:30). Jiang’s idea of Taiwanese identity subsequently evolved further into “Taiwanese in toto.” In mid-1927, when the authority publicly criticized this special usage of Jiang’s and demanded that it be changed into “this-islanders (hontōjin  ),” he responded,

),” he responded,

“This-islanders” refers only to the traditional Han people, so they can only mean the Han people in Taiwan, excluding Japanese and aboriginal tribes.… “Taiwanese” is a name based on living quarters. Therefore, broadly defined, “Taiwanese in toto” can include anyone residing in Taiwan. It is more adequate than “this-islanders,” which is especially for the Han people. (1998:212–213)

With the invention of Taiwanese in toto, Jiang seemed to have reached the end of his abilities in imagining national identity. Heavily involved in his Populist Party before his untimely death, he grew ever more sympathetic with socialism. The collective identity that concerned him now was no longer nation, but class (Jiang 1998:244, 302).

Therefore, in the 1920s and against a modernizing and assimilative background, Jiang Weishui’s imagination of Taiwanese national identity rapidly changed from that of Han origin to that of Fujian and Guangdong aborigines and, finally, to that of Taiwanese in toto. But his changing the collective name is just like changing the subject in a sentence: inevitably the predicate that describes the subject will have to change in order to maintain the sentence’s consistency both grammatically and substantively. Jiang’s discourse of national identity kept changing its subject, thus rendering his discourse totally ambiguous in regard to what he really thought of the issue. In this he was not alone in his quest of a proper definition of national identity, as our study of his contemporaries, Xie Chunmu and Cai Peihuo, will show.

For Xie, a journalist and a key cadre in Jiang’s party, the ambiguity of his sense of national identity was seen when asked whether he himself was a member of the “Chinese nation” or the “Han people in Taiwan.” From May to June 1929, Xie traveled extensively in Japan and China, where he reported on Dr. Sun Yat-sen’s national funeral held in Nanking, then the capital of China. In his travelogue, he reports that when he landed in Shanghai, he saw Indians serving as “loyal doormen of imperialism.” He could not help but compare the status of Indians to that of Chinese: “We Chinese people are trotting the same miserable route as they are … [and] we Taiwanese are not just slaves, we are slaves who have lost their nation” (Taiwan minpō 274 [1929]: 11). But this slave felt very much at home in Nanking, because individual Chinese were together again. Xie had heard that Chinese people were “persistent, enduring, and strong… As a member of this people, I hope all these qualities are true” (Taiwan minpō 276 [1929]: 12). He fully agreed with his fellow Taipeinese’ comment, “As an overseas Chinese, we should try our best to contribute to our ancestral place, the new republic” (Xie 1999:184).

However, by the time of his writing Taiwan had been separated from China for over three decades. Senses of difference had inevitably grown on both sides. Xie says, for example, “The most inconvenient thing in traveling in China is the Chinese’ lack of efficiency.” This kind of judgment frequently deteriorated into a “we Chinese, you Japanese” kind of quarrel. Worse still, Taiwanese working in China were accused of being “the running dogs of Japanese.… And if they want to change their nationality to that of Chinese, what are they going to do with their wives, kids, and especially, the ancestral graves in Taiwan?” (Xie 1999:295–296). Caught between the non-clear-cut identities of the Chinese nation and the Han people in Taiwan, he asked himself, “Which system is better for the inhabitants: a colony or a semi-colony?” (Xie 1999:259).14 Colonial subjects (Taiwanese) served one metropolis without any sense of autonomy, but semicolonial subjects (Chinese) served several metropolises with their own autonomy. In Xie’s view, Taiwanese as colonial subjects had only two options: bowing to their fate or rising up to fight. It took another three years after the death of Jiang Weishui for him to reach his decision; he opted for fighting and joined the Chinese army against Japan. Xie’s ambiguity regarding his national identity was real but short.

Finally, we come to Cai Peihuo, a brilliant social reformer in the early 1920s who, after Jiang Weishui founded the Populist Party, denounced the party and leaned toward a conservative, assimilative mode. The point of Cai’s social reform was to set up a special Taiwan council within the jurisdiction of the Japanese constitution in order that it could overview the budget and laws raised by the sōtokufu. In 1928 he put his ideas into a Japanese book, called Nihon honkokumin ni ataeru (To Japanese compatriots  ), in which he explained his understanding of national identity.

), in which he explained his understanding of national identity.

He called the Japanese his “compatriots” because, although they belonged to different “nations,” they “not only shared the same passport status but were comrades in terms of sharing a common humanity and a love of peace and freedom” (Cai 1928:29). The concept of “compatriots with different nationalities” was the ambiguity underlying Cai’s imagination of his national identity. Because they were compatriots, he demanded that Taiwanese be treated equally in political and economic affairs; but because they were of different “nations”—referring to “different languages, habits, and lifestyles” (1928:108–110)—the Japanese in Taiwan had both a sense of superiority to the Taiwanese and exploitative policies toward them. This was the reason why, in the 1920s, there arose a national consciousness in the minds of the Taiwanese (1928:43). Cai proposed a Taiwan council composed of local residents to help bridge the widening gap of national differences.

Furthermore, Cai criticized Japanese officials who tended to reject the possibility of Han people becoming His Majesty’s loyal subjects, because they thought that Han-Taiwanese did not possess Japanese nationality. It was “common humanity,” not “nationality,” that should be the criterion for compatriotship. “Nationality is subsumed in humanity” (1928:144). Since Confucianism had indoctrinated nothing but decent humanity in both Japanese and Taiwanese people, there was no reason why Han-Taiwanese could not become Japanese who were “loyal to the Emperor and patriotic to the state” (chūkun aikoku).

Once granted the Taiwan council by the Japanese Diet, Cai contended, the Taiwanese would not, and could not, pursue independence. There were four conditions that could then prevent the movement from succeeding: Japan continued its imperialist policy; Japan could not maintain its current power; the Taiwanese abandoned Confucianism and became a warlike people; and a strong nation came to Taiwan’s help in fighting with Japan (1928:181–182). None of these was acceptable to Cai, and he was determined to pursue limited Taiwanese’ autonomy under the Japanese empire’s tutelage.

In the thought of Cai Peihuo, compatriotship and nation were different but bridgeable; they required a common humanity, molded by the same Confucian learning, and an institutional innovation to convert one to the other. Unless the Japanese yielded to the demands of the Taiwan council, the “Han-ness” of the Taiwanese would be preserved precisely because of the Japanese colonizers’ superior sense of national identity.

In the discourses of Taiwanese nationalism, it was Cai whose thought most showed the influence of assimilationism. Pursuit of limited autonomy, inclination to chūkun aikoku, and the notion of the malleability of nationality all underlined his vagueness over the issue of national identity. This ambiguity also applied to Jiang Weishui and Xie Chunmu. There was the rapid change in the subject of nationalism, from that of Han origin to that of Fujian and Guangdong aborigines and to that of Taiwanese in toto on Jiang’s part. On Xie’s part, there was his hesitation between the Chinese nation and the Han people in Taiwan. The ambiguity inherent in the incipient Taiwanese nationalism came, we suggest, from the fact that, because of the Taiwanese nationalists’ complete Japanese education, their residual Han-culture could no longer be a resource for identity formation. Furthermore, the emergence of socialism was not yet strong enough to guide this nationalism. Finally, this ambiguity indicated the beginning of hegemonic control of Taiwanese intellectuals against the modernizing and assimilative background of the 1920s.

POLARIZED IDENTITY IN THE PERIOD OF HIGH JAPANIZATION (1931–1945)

On the periphery of the Japanese empire in the 1920s, Taiwan began to be upgraded to a “semi-periphery” by metropolitan politicians in the early 1930s. This was due to the military expansionism adopted by Japan. Especially after the Marco Polo Bridge incident in mid-1937, Taiwan served as a bridgehead to push Japan’s “Southbound” policy, that is, the military inroad upon both South China and Southeast Asia. Taiwan’s changed military status is important if we are to understand why the government-general relentlessly enforced the comprehensive cultural policy kōminka  (literally, to Japanize) during the last period (1931–1945) of its rule. It needed both loyal soldiers and resources to refuel Japan’s war machine.

(literally, to Japanize) during the last period (1931–1945) of its rule. It needed both loyal soldiers and resources to refuel Japan’s war machine.

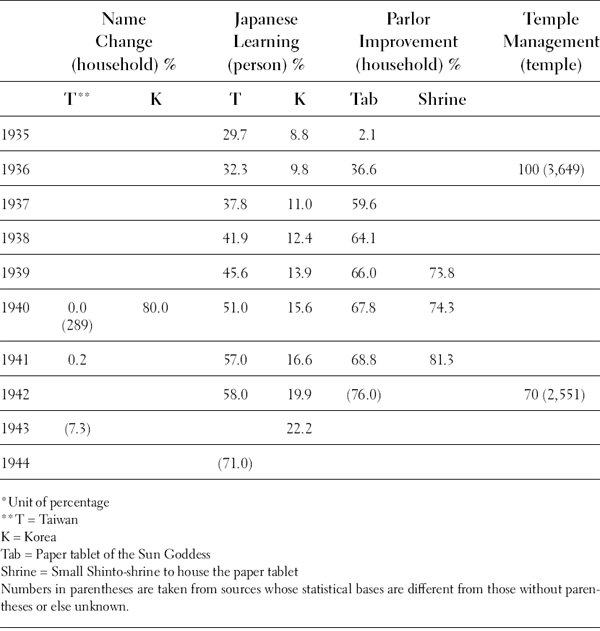

With each major military advance, notably the Marco Polo Bridge incident and the Pearl Harbor attack (1941), the sōtokufu redirected kōminka, under different names,15 to cope with the new reality. Over time we see a pattern of enhanced assimilating efforts, which reached a climax around 1940 and then diminished afterward, apparently due to a trade-off for extraction of wartime materiel. In the main, kōminka involved four cultural practices in regard to Taiwanese daily life: changing to Japanese-style names, teaching Japanese language, imposing upon families the worship of the Japanese sun goddess, Amaterasu  ,16 and abolishing both local temples and the idols they housed. Table 8.1 shows how effective these practices had been.

,16 and abolishing both local temples and the idols they housed. Table 8.1 shows how effective these practices had been.

TABLE 8.1 Statistics Supporting Weak Hegemony

Source: Cai 1990:319, 322; Ihara 1988:359; Uesuki 1987:156; Chen 1987:75, 78; Wu 1987, 37.4:71; Yokomori 1982:215–220.

From table 8.1, it is easy to infer that, except for the change in name, Taiwanese on the whole were very responsive to the new cultural policies of the sōtokufu. Their enthusiasm showed particularly in the learning and use of Japanese language. With over 70 percent of Taiwanese able to communicate in Japanese by 1944, it is no wonder that the short stories and novels regarding identity confusion that Taiwanese authors wrote were in Japanese.

But before discussing this identity issue, let us first say a word about the name-changing movement. Contrary to the commonly held opinion that name-changing was one of the most significant kōminka movements in the early 1940s (Ko 1981:167; Uesuki 1987:169) and that its poor result showed Taiwanese “lack of interest” or plain “resistance” (Ko 1981:168; Chen 1984:50; Chen 1987:78), we suggest that the Taiwan sōtokufu lacked the enthusiasm to promote the movement. Elsewhere we have documented that, in implementing the policy, the sōtokufu had bypassed the powerful neighbor-watching system (hokō  ) for help, imposed no deadline for application, and especially insisted that only the Japanese-speaking family could apply (Fong 1993). All this suggests that by 1940 the sōtokufu was reluctant to commit itself to this metropolitan-imposed policy of name-changing. If this interpretation is acceptable, then not all kōminka cultural policies were resisted by the Taiwanese, a further indication that Japanese hegemonic control was, by then, effective. However, it was a “weak hegemony” because only the educated upper Taiwanese class identified with kōminka. The rest of the population remained marginalized, outside hegemonic control. It is this polarized Taiwanese identity that is revealed in contemporary short stories and novels.

) for help, imposed no deadline for application, and especially insisted that only the Japanese-speaking family could apply (Fong 1993). All this suggests that by 1940 the sōtokufu was reluctant to commit itself to this metropolitan-imposed policy of name-changing. If this interpretation is acceptable, then not all kōminka cultural policies were resisted by the Taiwanese, a further indication that Japanese hegemonic control was, by then, effective. However, it was a “weak hegemony” because only the educated upper Taiwanese class identified with kōminka. The rest of the population remained marginalized, outside hegemonic control. It is this polarized Taiwanese identity that is revealed in contemporary short stories and novels.

Taiwanese fiction during the kōminka period may be classified into two genres: that of the masses and that of the intellectuals. The mass genre underlined the socioeconomic predicaments of minority groups—mainly the poor and women who were tradition bound, while the intellectual genre constituted a grand narrative of the elite immersion into Japanese identity.

The situation of poverty, as described in the mass genre, was best symbolized by the image of the “public steelyard.” In “Overload” (Zhang 1935), a mother carrying a baby and a load of bananas (which weigh 36 kilograms) walks 6 kilo-meters to the market with her twelve-year-old son, who carries another load of 12 kilograms. She sells all the bananas for 48 qian  but is responsible for paying the use of the public steelyard (3 qian) and sales tax (8 qian for 48 kilograms). She pleas for mercy with the policeman in charge of collecting the money. After being humiliated, she still has to pay all 11 qian.

but is responsible for paying the use of the public steelyard (3 qian) and sales tax (8 qian for 48 kilograms). She pleas for mercy with the policeman in charge of collecting the money. After being humiliated, she still has to pay all 11 qian.

In “A Steelyard” (Lai 1926), Chin sells vegetables in the market. A policeman wants to take the produce for free. Chin does not agree to this and is fined on the pretext of using an imprecise private steelyard. Next day, the Chinese Lunar New Year’s Eve, the cop shows up again and this time puts Chin in jail for three days, presumably because he did not use the steelyard at all and thus broke the law. Bailed out by his wife, Chin kills the cop that night and commits suicide.

In addition to Japanese police brutality, women’s predicaments were often explored in the mass genre. Not only were they depicted as their husbands’ scapegoats, they were often trapped on a dead-end road, becoming first concubines and then prostitutes. In his short story of 1935, Lu Heruo  first describes how the modern highway replaced trails and caused the drivers of oxcarts to become unemployed. One such unfortunate driver, Young, thus asks his wife to sleep with his creditors. Lu also tells the story of a tenant who could only keep his farmland by letting his wife become the landlord’s mistress. Worse, because of poverty and male chauvinism, Taiwanese families often sent their baby girls to be adopted by the rich. The fate of these girls was miserable. In one story (Zhang 1941), a fourteen-year-old Caiyun was sent to keep a sixty-year-old man company for three days because her adopted mother had received a thousand yan and a golden bracelet from him. She was then sent to become a geisha. In another (Lu 1936), a dancing girl, Shuangmei, was forsaken by her boyfriend after six years of cohabitation. In order raise their daughter, she decides both to become a prostitute and to train the daughter to follow in her steps for revenge.

first describes how the modern highway replaced trails and caused the drivers of oxcarts to become unemployed. One such unfortunate driver, Young, thus asks his wife to sleep with his creditors. Lu also tells the story of a tenant who could only keep his farmland by letting his wife become the landlord’s mistress. Worse, because of poverty and male chauvinism, Taiwanese families often sent their baby girls to be adopted by the rich. The fate of these girls was miserable. In one story (Zhang 1941), a fourteen-year-old Caiyun was sent to keep a sixty-year-old man company for three days because her adopted mother had received a thousand yan and a golden bracelet from him. She was then sent to become a geisha. In another (Lu 1936), a dancing girl, Shuangmei, was forsaken by her boyfriend after six years of cohabitation. In order raise their daughter, she decides both to become a prostitute and to train the daughter to follow in her steps for revenge.

Lu Heruo’s artistic talent and his concern for the underclass in Taiwanese tradition reached its peak in the early 1940s. In order to expose the contradictions within traditional families, he created an evil character, Zhou Wenhai, in “Wealth, Sons, and Longevity” (1942). Zhou, as the elder son and, hence, householder, causes every kind of misery for other family members. His brother’s family is expelled from the ancestral house under his charge. He rapes his maid, who then competes with his wife for his favor. His wife subsequently goes crazy. His ancestral house is called the Hall of Happiness and Longevity, an ironic name that contrasted with what Zhou does to betray it.

However, the real gem of Lu’s achievement is his “Pomegranate” (1943). Here he tells the story of two orphaned brothers, Jinsheng and Muhuo. Jinsheng married into his wife’s house and became less than a man in the Taiwanese value system, while Muhuo was adopted by a clansman. One day Muhuo, who was single, went mad and accidentally died without a son; he thus could not be worshiped by his offspring and become an ancestor. To solve this lineage problem, Jinsheng, being poor, seeks to combine two rituals—one to put Muhuo’s name on the wooden ancestral tablet that Jinsheng, as an elder son, had to keep, the other to let Jinsheng’s son be adopted by Muhuo in order for them to worship him—together. The description of how the rituals were held at night and away from the family of Jinsheng’s wife are meticulous and filled with such folk knowledge that the story moves its readers.

In its depiction of police brutality (as symbolized in the steelyard), the unequal status of women, and the Han-tradition, which perpetuated minority groups’ miseries, the mass genre in fact kept the underclass away from the Japanese hegemon. Being exploited and humiliated, the weak were reminded in their daily life that they were insignificant and marginal, an enduring experience that effectively served as an antidote against Japanization indoctrination. Their immunization was further reinforced by residual Taiwanese culture, as seen in Jinsheng’s performance of the rituals of ancestral worship and son adoption. It was doubtful whether people like Jinsheng really understood the meaning of these rituals. But by enacting the form of the rituals to address their daily concerns, they were empowering the tradition to reaffirm their Taiwanese identity. The residual culture, however, could not serve the same purpose for the Japanese-educated Taiwanese upper class; they actively responded to the calling of kōminka and sought from the bottom of their hearts to Japanize themselves. Their experience, as captured in fiction, constituted the intellectual’s genre.

Taiwanese elites’ change of heart was first set forth in the short story “The Little Town with Papaya Trees” (Long 1937). After graduating from high school, Chen cannot find a job for five years. Finally he becomes an accounting assistant in a township government through civil examination. As a clerk, he decides he must either pass the exam for an accountant certificate or marry a Japanese girl and become a Japanese himself (then he would get a 60 percent raise in his salary). Frustrated in both attempts, he gradually adopts the lifestyle of his Taiwanese associates—lustful, alcoholic, and greedy.

If Chen’s degeneration was largely caused by the colonial environment, this was plainly not the case in the 1941 story of Zhang Minggui, Chen Qingnan, or Itō. In “Voluntary Soldiers” (Zhou 1998), Minggui, a college student just returned from Japan, gets into an argument with his friend, Gao Jinliu, over how to become a Japanese. Gao’s method is “mysterious”: he thinks that only by obeying strictly the Shintō ritual of kashiwade  (clapping hands) can one’s Taiwanese soul be cleansed and become Japanese. Minggui’s solution, however, is essentially based on self-recognition: “Born in Japan, raised up in the Japanese language, knowing nothing but Japanese kana, I have to be a Japanese to survive” (Zhou 1998:35). It was this recognition of forced Japanization that revealed Taiwanese intellectuals’ understanding that, at best, they could strive to be second-class Japanese. This sub-Japanese complex was reincarnated in Itō, while Gao’s Shintō way toward becoming Japanese is embodied in Chen Qingnan.

(clapping hands) can one’s Taiwanese soul be cleansed and become Japanese. Minggui’s solution, however, is essentially based on self-recognition: “Born in Japan, raised up in the Japanese language, knowing nothing but Japanese kana, I have to be a Japanese to survive” (Zhou 1998:35). It was this recognition of forced Japanization that revealed Taiwanese intellectuals’ understanding that, at best, they could strive to be second-class Japanese. This sub-Japanese complex was reincarnated in Itō, while Gao’s Shintō way toward becoming Japanese is embodied in Chen Qingnan.

In the story of “The Way” (Chen 1943), Qingnan puzzles over the transformation of “Taiwanese I” into “Japanized I.” He first seeks inspiration from his Japanese colleagues but soon realizes that it is only being born with Japanese blood that would make one Japanese. This means training oneself to possess the Japanese spirit, which boils down to being loyal to the emperor and being patriotic to the state. To have this spirit, Qingnan tries to marry a Japanese girl (which fails), to worship the Sun Goddess, and finally to become a voluntary Japanese soldier. “To be loyal to the emperor amounts to death”: these were Qingnan’s last words and belief.

The sub-Japanese issue reappears in “Torrent” (Wang 1943). Itō Cunsheng wants to become Japanese so badly that he changes his Taiwanese surname, marries a Japanese, and lives in his wife’s house so that he speaks nothing but Japanese. Even at his father’s funeral, he refuses to practice the Chinese ritual of kneeling down before the coffin. The narrator reveals that, in his early thirties and desperate to be come Japanese, Itō has already turned his hair gray.

Itō’s choices are contrasted with those of his cousin and student, Lin Bonian, in the same story. Lin is on bad terms with Itō because he did not care about his own mother, Lin’s aunt. Lin is good at the Japanese art of sword play and won the championship over his Japanese schoolmates. Subsequently, Lin, against his parents’ wish but with Itō’s financial help, goes to Japan to study the art of the sword. He writes a letter, asserting that “to be an honorable Japanese I have to be an honorable Taiwanese first.” However, one wonders if Lin is too young to say this. Who knows what he would become, given that he would spend years studying in Japan?

In the intellectual genre, the key issue was not Taiwanese identity at all. It was about the means to become a fully Japanese, which involved both mysterious (Shintō  ) and rational paths. Particularly in the rational path, the identity-seekers knew perfectly well that they were imitating the Japanese way and that the best they could hope to achieve was a second-class Japanese nationality. Contrasting this genre with the mass genre, we suggest the Han-Taiwanese in the early 1940s had effectively been polarized into two identity groups: the educated elites who imagined themselves to be sub-Japanese and the underclass majority who had not yet forgotten their Han-ness. We attribute this polarizing effect to the hegemonic attempts of the Japanese colonizers, what might be called the success of the “weak hegemony.”

) and rational paths. Particularly in the rational path, the identity-seekers knew perfectly well that they were imitating the Japanese way and that the best they could hope to achieve was a second-class Japanese nationality. Contrasting this genre with the mass genre, we suggest the Han-Taiwanese in the early 1940s had effectively been polarized into two identity groups: the educated elites who imagined themselves to be sub-Japanese and the underclass majority who had not yet forgotten their Han-ness. We attribute this polarizing effect to the hegemonic attempts of the Japanese colonizers, what might be called the success of the “weak hegemony.”

CONCLUSION

In the cultural domain of the Japanese colonial project, coercion and remuneration were administrative practices constantly at the rulers’ disposal. Hence, in the Seiraian incident, it was the sheer brutality of the military strength that suppressed the Taiwanese rebels. The death penalties for the captives, 866 altogether, were soon reduced to life imprisonment due to the rescript of amnesty issued in celebration of the enthronement of Emperor Taishō  in 1915. It was a substantive favor that reinforced the coercive power of the colonial government. Furthermore, in the agitation of nationalism in the 1920s, countless arrests of Taiwanese advocates and the banning orders of their gatherings and public speeches all testified to the power of the Japanese police, whose atrocities also had a salient presence in the mass genre of Taiwanese fiction.

in 1915. It was a substantive favor that reinforced the coercive power of the colonial government. Furthermore, in the agitation of nationalism in the 1920s, countless arrests of Taiwanese advocates and the banning orders of their gatherings and public speeches all testified to the power of the Japanese police, whose atrocities also had a salient presence in the mass genre of Taiwanese fiction.

During this decade, higher education became the sōtokufu’s tool for buying off the Taiwanese elite families. To study in the metropolis they would need special permission from the administration; family business in wines, tobacco, salt, and rice all required the sōtokufu’s licenses. Finally, during the Pacific War, military power and martial laws again replaced the police in keeping peace on Taiwan island. Material quotas were set up, but those who adopted Japanese names and spoke Japanese were given double or triple shares. Coercive and remunerative powers were always present to enhance the colonizer’s indoctrination attempts.

However, from the discourse of bandits, to that of assimilation, and finally to kōminka, the effect of the sōtokufu’s moral appeal was on the whole limited. Not only was the banditry discourse countered by the religious imagination of the Seiraian rebels’ ideal self, the discourse of assimilation was also seriously circumscribed by Taiwanese nationalism. The changing subjects in the incipient ideology of nationalism also revealed the ambiguity in the Taiwanese elites’ imagination of national identity, the first sign of the effectiveness of the hegemonic control. It was in the period of high Japanization and among the cultural practices (of name-changing, the enhancement of Japanese literacy, parlor improvement, and temple management) that the polarizing effect of hegemonic discourse was seen. Since the effect only brainwashed some Taiwanese intellectuals into believing they possessed the Japanese spirit (tacitly understood as a second-class spirit), what Japanese had achieved must be judged to be a weak hegemony.

To the underclass of Taiwanese colonial subjects, their discourses in Seiraian and, later, in the mass genre of fiction consistently suggest that it was the residual culture from their precolonial life that was the fundamental source of their collective identity. We can distinguish this identity as a traditional one, which, up to the 1910s, still was free of any contamination from the colonial project, and a proto-national one, molded in the daily experience of being humiliated and exploited under the regime. In either case, the Taiwanese underclass was immune to the Japanese hegemon.

It was Taiwanese intellectuals who were fully immersed in Japanese education and who eventually became the fifth column of the Japanese colonizers. In the short stories told about them during kōminka, they were portrayed as enthusiasts for becoming Japanese, often by way of rational or irrational means. It is not surprising, given that the colonial project was also a modern project, that one could not be addicted to the latter (as indicated by Chen Shaoxin’s description) without being trapped in the former at the same time. They had contributed to the success of the weak hegemony.

One wonders, however, what would have become of this colonial project had there been no Pacific War. Most likely the hegemonic success would have spread and the Taiwanese would have become no different from the people of Okinawa, for four centuries an independent nation under the name of Ryukyu but now a periphery of Japan and suffering continuing discrimination from the metropolis.

NOTES

1. This customs movement included cutting Han-Taiwanese’ queues, unbinding Han-women’s feet, and stopping opium-smoking (TSKE 1938, 2:741–752).

2. Viceroy Kodama, who made his career in suppressing the “bandits,” had his own classification of seven types, based on why they had become bandits: (1) because, in the process of an army expedition, they had suffered either from scouts’ mistranslation or from improper killings; (2) because they had lost their jobs due to the law “regulation of the mining industries”; (3) because they had lost their jobs due to the new system of recruiting guards against aborigines; (4) because they were coerced by other bandits; (5) because they believed other bandits’ rumors and lies; (6) because they had committed crimes in Qing China and fled to Taiwan; (7) for revenge against the Japanese army and police who had killed their parents or siblings (this is the largest category) (Tsurumi 1944, 2:1356).

3. For example, the former Qing soldiers, once caught, would be sent back to mainland China; the gangsters would be sentenced to death; and common-folks-turned-rebels would be given a second chance to lead a normal life.

4. In the 268-year reign of the Qing Dynasty, there occurred 148 riots waged by Han-Taiwanese immigrants from mainland China. Of these riots, 85 were classified as rebellions against the Qing government and 63 as clan struggles (Weng 1986:44).

5. This was one of the most fundamental tenets of Japanese fascism before and during World War II.

6. The last sentence, in brackets, was taken from the site of an ellipsis in the citation.

7. In one sociological account, “modernity has operated with the rationality/irrationality distinction as its core organizing code” (Albrow 1996:56). Hence the expansion of technological rationality into the fields of health, agriculture, and transportation, as indicated in Chen’s words, certainly serves as a criterion for distinguishing the modern from the premodern.

8. Shibata Sunao was a social scientist who was responsible for the first and the only official religious survey (1915–1917) in the Taihoku area (Masuda 1939:234). He had lived in Taiwan for eleven years before he published the book. His book was apparently well received, and went into a second printing in less than six months. The second printing drew favorable reviews from major newspapers and magazines in both Taiwan and Japan.

9. An editorial in Taiwan Minpō (1925, 3.6:1) summarized Viceroy Den’s gradual assimilative policy of interior extensionism: “[T]he policy is first implemented in the easily done aspect—substituting local Taiwanese names with Japanese ones. It then gradually eliminates the written Chinese language (hanwen) and replaces it with Japanese for daily use. It subsequently transplants the Japanese legal system to Taiwan.”

10. Nakanishi Ushio was a key supporter of Itagaki Taisuke  ’s assimilation society, which was established in Taipei in January 1915 but banned two months later. In fact, he wrote Dōkaron, in classical Chinese, both to advocate Itagaki’s idea—namely, Taiwan should be assimilated into Japan so that the Taiwanese could bridge the relationship between Japan and China in fighting against the white race—and to impress traditional Taiwanese Confucians (see Ye 1971:15).

’s assimilation society, which was established in Taipei in January 1915 but banned two months later. In fact, he wrote Dōkaron, in classical Chinese, both to advocate Itagaki’s idea—namely, Taiwan should be assimilated into Japan so that the Taiwanese could bridge the relationship between Japan and China in fighting against the white race—and to impress traditional Taiwanese Confucians (see Ye 1971:15).

11. It may be inferred that Shibata here was pointing to what the young Taiwanese intelligentsia had been doing in Tokyo (publishing Taiwan Youth and petitioning for a Taiwan legislature) and in Taiwan (opening up island-wide cultural associations, which served as the initial institutional base for the fourteen-year “petitionary movement for establishing a Taiwan legislature”).

12. Nakanishi used synonyms and parallel phases to express this rescript phase, but I shall stick to the official English translation. After the Manchuria incident in 1931, the phase was changed to “the unbroken imperial line” (banseiikkei). This new phase suggests that Nakanishi’s view on the Japanese national essence was a widely accepted one.

13. Jiang Weishui was sympathetic to the Taiwanese Communist Party (founded in Shanghai in 1928), and became more so toward the end of his life. However, he firmly directed his new party away from both radical socialism and pro-Japanese conservatism.

14. “Semi-colony” was a term made famous by Dr. Sun Yat-sen, who used it to refer to the status of China when it conceded enclaves to several imperial powers, including Great Britain, France, and Japan, in the early 1920s.

15. At the end of 1935, the Bureau of Culture and Education of Sōtokufu promoted “the movement for exalting civilian customs” (minpū sakkō undō  ), which was restructured as “the general movement for mobilizing the national spirit” (kokumin seishin sōdōin undō

), which was restructured as “the general movement for mobilizing the national spirit” (kokumin seishin sōdōin undō  ) in 1937, an event modeled after the same movement, with different emphases, in Japan proper. In mid-1941, before Pearl Harbor but after Japan’s alliance with Germany and Italy, the movement was retitled and restructured as “the movement for the devotion of the Emperor’s subjects to the national course” (kōmin hōkō undō

) in 1937, an event modeled after the same movement, with different emphases, in Japan proper. In mid-1941, before Pearl Harbor but after Japan’s alliance with Germany and Italy, the movement was retitled and restructured as “the movement for the devotion of the Emperor’s subjects to the national course” (kōmin hōkō undō

; Taiwan jihō [Taiwan times] 11 [1937]: 10; 6 [1941]: 37).

; Taiwan jihō [Taiwan times] 11 [1937]: 10; 6 [1941]: 37).

16. This practice was called the “parlor improvement” movement, because every family had to set up a small shrine to contain a sacred paper tablet, the symbol of Amaterasu, in its parlor, or living room.

REFERENCES

Ajiken (Ajia keizai kenkyusho), ed. 1973. Union Catalogue of Publications by Former Colonial Institutions—Taiwan. Tokyo: Institute of Developing Economics.

Albrow, Martin. 1996. The Global Age: State and Society Beyond Modernity. Stanford: Stan-ford University Press.

Ang Kaim. 1986. Taiwan hanren wuzhuang kanrishi yanjiu (1895–1902) [Taiwanese armed resistance under early Japanese rule (1895–1902)]. Taipei: Taiwan National University.

Anonymous. Dadongjing [The book of the immense cave]. Tainan: Songyunxuan.

———. 1912–1915. Jingxinpian [The book of the alert heart]. Tainan: Seiraian.

———. 1862. Wugongjing [The book of five masters]. Tainan: Songyunxuan.

Cai Jintang. 1990. “Riju shiqi de taiwan zongjiao zhengche yanjiu: Fengsi ‘shengong dama’ji faxing shengong li [A study of the religious policy in Taiwan under Japanese rule: The worship of the paper tablet and the circulation of the calendar from the Sun Goddess’ shrine].” In Zheng Liangsheng, ed., Dierjie zhongguo zhengjiao guanxi guoji xueshu yantaohui lunwenji [The second international symposium on politico-religious relations in China]. Taipei: Department of History, Danjiang University.

Cai Peihuo. 1928. Nihon honkokumin ni ataeru [To Japanese compatriots]. Tokyo: Taiwan mondai kenkyūkai.

Chen Huoquan. 1943. “Dō [The way].” Bungei Taiwan [Literature and art of Taiwan] 6.3:87–141.

Chen Jinzhong. 1977. “Xilaian kangri shijian zhi xingzhi quantan—jiu qishi ‘yugaowei’ fenxi [A preliminary study of the nature of the Seiraian anti-Japanese incident: An analysis of its “Declaration of War”]. Donghai daxue lishi xuebao (Donghai University: Journal of history) 1:147–158.

Chen Renkui. 1984. “Riju meqi taibao dizhi ‘huangminhua’ yundong zhi tantao [A discussion of Taiwanese’ resistance to the kōminka movement at the end of Japanese occupation].” Taiwan wen hsien [Archival materials of Taiwan] 35.1:45–52.

Chen Shaoxin. 1979. Taiwan de renkou bianqian yu shehui bianqian [Population and social change in Taiwan]. Taipei: Lianjing.

Chen Xiaochong. 1987. “1937–1945 nian Taiwan huangminhua yundong shulun [A discussion of the kōminka movement in Taiwan from 1937 to 1945].” Taiwan yanjiu jikan [Taiwan research quarterly] 18:72–81.

Etzioni, Amitai. 1975. A Comparative Analysis of Complex Organization. Rev. and enlarged ed. New York: Free Press.

Fong Shiaw-Chian. 1993. “Achieving Weak Hegemony: Taiwanese Cultural Experience Under Japanese Rule, 1895–1945.” Ph.D. diss., Chicago: University of Chicago.

Gramsci, Antonio. 1971. Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. New York:International Publishers.

Hobsbawm, Eric J. 1959. Primitive Rebels. New York: Norton.

Igeda Toshio. 1981. “Yanagita Kunio yu Taiwan—Seiraian shijian de chaqu [Yanagita Kunio and Taiwan: An episode of the Seiraian incident].” Trans. Cheng Daxue. Taiwan wen hsien 32.3:180–202.

Ihara Kichinoshke. 1988. “Taiwan no kominka undo—shōwa junendai no taiwan (2) [The kōminka movement in Taiwan: Taiwan in the second decade of Shōwa (2)].” In Nakamura Koshi, ed., Nihon no nanpo kanyo to taiwan, 271–386. Nara: Tenrikyo doyusha.

Jiang Weishui. 1998. Jiang Weishui quanji [The complete works of Jiang Weishui]. Ed. Wang Xiaobo. Taipei: Haixia xueshu chubanshe.

Ko Shodo. 1981. Taiwan sōtokufu [The government-general of Taiwan]. Tokyo: Kyoikusha.

Lai Ho. 1926. “Yigan chenzi [A steelyard].” Taiwan minpō [Taiwan people’s news] 92 (February 4), 93 (February 21).

Long Yingzong. 1937. “Papaya no aru machi [The little town with papaya trees].” Kaizō[Tokyo] 19.4.

Lu Heruo. 1935. “Gyūshya [Oxcart].” Bungaku hyōron [Review of literature] 2.1.

———. 1936. “Ona no baai [The fate of woman].” Taiwan bungei 3.7–8:11–36.

———. 1942. “Jai ko jyū [Wealth, sons, and longevity].” Taiwan bungaku [Taiwan literature] 2.2:2–37.

———. 1943. “Jakuro [Pomegranate].” Taiwan bungaku 3.3:169–188.

Lukes, Steven. 1974. Power: A Radical View. London: MacMillan.

Masuda Fukutaro. 1939. Taiwan no shukyo: Noson o chushin to suru shukyo kenkyu [Religions in Taiwan: A religious study centered on villages]. Tokyo: Yokendo.

Nakanishi Ushio. 1914. Dōkaron [On assimilation]. Taihoku.

Ricoeur, Paul. 1992. Oneself as Another. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Shibata Sunao. 1923. Taiwan dōkasaku ron [On the assimilative strategy in Taiwan]. Taihoku: Kobunkan.

Somers, Margaret. 1994. “The Narrative Constitution of Identity: A Relational and Network Approach.” Theory and Society 23.5:605–649.