(1871–1945), who continuously used his watercolors and essays to report on what he observed in Taiwan, starting from the time of his first arrival in 1907.

(1871–1945), who continuously used his watercolors and essays to report on what he observed in Taiwan, starting from the time of his first arrival in 1907.COLONIAL TAIWAN AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF LANDSCAPE PAINTING

FROM JAPAN TO TAIWAN: DOCUMENTARY ART HISTORY

In modern times appreciation of the Taiwanese landscape, or the “construction” of landscape painting, gradually began taking shape after Japan established the colonial government, which then provided subjective and institutional guidance. The leading figure in the early phase of this process, and the person whose perceptions were most important, was Ishikawa Kinichirō  (1871–1945), who continuously used his watercolors and essays to report on what he observed in Taiwan, starting from the time of his first arrival in 1907.

(1871–1945), who continuously used his watercolors and essays to report on what he observed in Taiwan, starting from the time of his first arrival in 1907.

Ishikawa was a multitalented individual, gifted as both a watercolorist and a writer. His loyal followers in Taiwan praised him for being a modest, self-disciplined gentleman, a poet, and an artist. His painting skills “combined the character of Western painting with that of Nanga [ ]. His style was simultaneously that of naturalism, pleinairism, and Impressionism. He could be called Japan’s Corot (1796–1875), Turner (1775–1851), or Millet (1814–1875).”1

]. His style was simultaneously that of naturalism, pleinairism, and Impressionism. He could be called Japan’s Corot (1796–1875), Turner (1775–1851), or Millet (1814–1875).”1

In his 1926 essay, “Appreciating the Landscape of the Taiwan Region,” written after he had lived in Taiwan almost ten years, Ishikawa wrote, “To appreciate Taiwan’s landscape, one must first make a contrast and consider it from the perspective of the Japanese landscape.”2 Whenever this initiator of modern Taiwanese art looked at Taiwan’s landscape and, indeed, any scene of natural or human interest, he was always reflecting on his homeland, Japan. He would view the “virgin territory” of Taiwan through the filter of a traditional understanding of Japan’s natural and manmade scenery. Like many other cultural figures of the Meiji period, Ishikawa was especially talented as a writer of travel literature. Only three months after he retired and returned to Japan in April 1932, he published an essay, “Taiwan’s Landscape,”3 in which he provided a composite evaluation of the various characteristics of Taiwan’s landscape. He strongly emphasized general first impressions. For instance, “When one first arrives in Taiwan and gazes afar at the scene of Kheelung from the deck of one’s ship, the most enjoyable aspects are the fullness of natural color and the powerful contours of the mountains.” In 1935, when he once again reviewed his Taiwan experiences, he repeated that he would never forget his first impressions of Taiwan. He used general, strongly contrastive language: “According to legend, the place is hell, but once one sees it, it becomes heaven. This was my first impression of Taiwan. It is an island of very beautiful forms and colors, and it is pleasing.”4

In his early years, when Ishikawa worked for the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (seiheikyoku  ) in the Finance Ministry, he was a member of the Meiji Fine Arts Society (meiji bijutsukai

) in the Finance Ministry, he was a member of the Meiji Fine Arts Society (meiji bijutsukai  ) and a well-known painter of tourist sites in Yokohama.5 Watercolor paintings were then at the leading edge of the introduction of Western-style painting to Japan, and Japanese artists used watercolors to introduce Japanese scenes and local customs to foreign tourists. The functional aspect of watercolor matched Ishikawa’s fondness for travel, his erudition, and his powerful memory, but he also considered watercolor to be a Western medium that could fully express the flavor of Japan.6

) and a well-known painter of tourist sites in Yokohama.5 Watercolor paintings were then at the leading edge of the introduction of Western-style painting to Japan, and Japanese artists used watercolors to introduce Japanese scenes and local customs to foreign tourists. The functional aspect of watercolor matched Ishikawa’s fondness for travel, his erudition, and his powerful memory, but he also considered watercolor to be a Western medium that could fully express the flavor of Japan.6

In 1900, when Japan joined the eight allied powers to put down the Boxer Rebellion in China, Ishikawa used his English and painting skills to serve as a translator at the Japanese army headquarters. He once received orders to sketch a battle in progress for presentation to the Meiji emperor.7 In 1907, when he came to Taipei again as an army translator, he was already a well-known Tokyo watercolorist and an important contributor of essays to Mizue (Watercolor, a monthly journal established in 1905). During his first sojourn in Taiwan, from 1907 to 1916, his main outlets remained the Japanese art circles and magazines. Each year, like a migrating bird, he traveled back and forth between Taiwan and Japan.8

From his writings, one can readily deduce that he wished to report on Taiwan’s landscape, and that his anticipated reading audience consisted of Japanese people who had never visited Taiwan or who had not stayed in Taiwan very long. His first essay published after arriving in Taiwan, “Watercolor Painting and Taiwan’s Scenery,” encouraged Japanese amateur painters who lived in Taiwan to make use of watercolor’s convenience, and introduce Taiwan’s beautiful scenery to friends in Japan.

In his early reports, he expressed the thought that the colors of Taipei’s old street scenes were more beautiful than their counterparts in Japan. “The red eaves and yellow walls, matched with the green of the bamboo groves, create an effect of thorough intensity. The green of the acacia trees presents a deep majesty never seen before in Japan, and under the blue of the sky it becomes even more exquisite.”9 The images that created his initial impressions, such as houses, bamboo, acacias, and so on, became the main subject matter of Ishikawa’s Taiwanese landscapes, such as Little Stream (fig. 11.1). Depicting an arched stone bridge on one of Taipei’s old streets, the painting was admitted to the Bunten ( ; Ministry of Education art exhibition) in 1908. It would be no exaggeration to say that this was his interpretation of what was to him exotic about Taiwan’s special qualities or an equivalent of southern China’s rich colors.

; Ministry of Education art exhibition) in 1908. It would be no exaggeration to say that this was his interpretation of what was to him exotic about Taiwan’s special qualities or an equivalent of southern China’s rich colors.

FIGURE 11.1 Ishikawa Kinichirō, Little Stream, 1908.

PAINTINGS OF MOUNTAINS AND THE POLICY OF “CIVILIZING BARBARIANS”

The early development of Taiwanese landscape painting paralleled the opening and exploitation of the aboriginal lands in the mountains. The complex relationship between these developments involves many issues deserving of attention. The first concerns the subjugation of the aboriginal peoples.

Ishikawa’s first arrival as an army translator coincided with the campaign led by Army General and Governor-General Sakuma Samata  (1844–1915) to militarily subjugate “untamed barbarians” in the mountains so that the forest resources could be exploited. The bloody battles in the mountains lasted ten years.10 In the early period of Ishikawa’s stay in Taiwan, he produced many paintings of the historic battles undertaken to subjugate Taiwan. One of his monumental battleground pictures was hung up in the main hall of the new Taiwan Governor Museum in 1909.11

(1844–1915) to militarily subjugate “untamed barbarians” in the mountains so that the forest resources could be exploited. The bloody battles in the mountains lasted ten years.10 In the early period of Ishikawa’s stay in Taiwan, he produced many paintings of the historic battles undertaken to subjugate Taiwan. One of his monumental battleground pictures was hung up in the main hall of the new Taiwan Governor Museum in 1909.11

That same year Ishikawa was ordered to enter the central mountain range from Puli and draw topological maps of barbarian territories. He was accompanied and guarded by twenty soldiers, and the entire party, including policemen, translators, and porters, formed a line more than one hundred meters long. Along the guarded perimeter of their encampments, Ishikawa set up tables and chairs to paint large watercolors. Occasionally the guards next to him fired off warning shots toward the mountains, setting off wave after wave of echoes. Ishikawa recalled how he had had to conceal his sketching work on the Tianjin battleground in China, and how this time the work was different: “This time I could spend long periods of time in the open on the perimeter painting the scenery. It was a happy experience that I will never forget.”12 These sketches were sent personally from the governor-general to Tokyo, where they were presented to the Meiji emperor to promote his success in “civilizing barbarians.” It was reported that the emperor “was extremely satisfied” with the work.13

During this period, when the Japanese army was subjugating aboriginal tribes in the mountains, many Japanese artists like Ishikawa followed the army deep into the mountains to explore and discover new subject matter. These early artists maintained good relations with the military, and after they finished their paintings they would always present the works to the governor-general and other officials. For its part, the colonial government never tired of using art to promote its grand accomplishments.

However, the first persons to enter the mountain territories after Japan took control of Taiwan in 1895 and to study the aborigines had in fact been anthropologists from Tokyo University, such as Torii Ryūzō  (1870–1953).14 The explorer Mori Ushinosuke

(1870–1953).14 The explorer Mori Ushinosuke  (1877–1926) became acquainted with Torii in Taiwan in 1895 and became his loyal assistant and correspondent in Taiwan. Mori, who studied the aborigines for more than twenty years, not only published descriptive articles under the heading “Correspondence from Taiwan” in the Tokyo Anthropology Magazine (Tōkyō jinruigaku zasshi

(1877–1926) became acquainted with Torii in Taiwan in 1895 and became his loyal assistant and correspondent in Taiwan. Mori, who studied the aborigines for more than twenty years, not only published descriptive articles under the heading “Correspondence from Taiwan” in the Tokyo Anthropology Magazine (Tōkyō jinruigaku zasshi  ) but also wrote large numbers of expedition reports for the Taiwanese newspaper Taiwan nichinichi shinpō

) but also wrote large numbers of expedition reports for the Taiwanese newspaper Taiwan nichinichi shinpō  and the monthly Taiwan jihō

and the monthly Taiwan jihō  (Taiwan times). Sponsored by the colonial government, he also published Illustrated Guide to Taiwan’s Barbarian Tribes (Taiwan banzoku zufu

(Taiwan times). Sponsored by the colonial government, he also published Illustrated Guide to Taiwan’s Barbarian Tribes (Taiwan banzoku zufu  , 1915; 2 vols.) and Record of Taiwan’s Barbarian Tribes, vol. 1 (Taiwan banzoku shi dai-ikkan , 1917). These were used as handbooks for learning about Taiwan’s aboriginal peoples, and they were widely read.15

, 1915; 2 vols.) and Record of Taiwan’s Barbarian Tribes, vol. 1 (Taiwan banzoku shi dai-ikkan , 1917). These were used as handbooks for learning about Taiwan’s aboriginal peoples, and they were widely read.15

The anthropologists’ exploratory activities took place primarily during the first ten years of Japan’s rule of Taiwan, when the mountain regions were still basically at peace. They were able to gather a wealth of material in a very short period of time. The anthropologists’ detailed, lively reports not only became the artists’ guidebooks in the mountains and inside their studios—they also became a primary resource for the colonial government as it exploited and oppressed the aborigines under its “civilizing barbarians” policy. If we consider events from this perspective, might it be that while Ishikawa was happily sitting among soldiers at his table in the mountains, depicting the scenery of the central mountain range, he was thinking about the role played by artists under the colonial government?

SUBJECTIVITY AND OBJECTIVITY IN CULTURAL AND ARTISTIC VIEWS

In 1924, one year after he experienced the Great Tokyo Earthquake, Ishikawa was offered a position as art instructor at Taipei Normal School. By this time, Taiwan was being administered by civil, not military, officials, and Ishikawa considered the job offer to be a great opportunity to promote watercolor painting, which had been steadily losing importance in Japan’s Western painting circles. Meanwhile, in Taiwan, where art education was just beginning its development, Ishikawa could fully devote himself to spreading his knowledge and techniques.

Ishikawa took seriously his role as a disseminator of culture. For instance, in 1925, he published a painting or an essay almost every other day in the newspaper Taiwan nichinichi shinpō. He also published numerous articles on painting techniques and basic appreciation in the monthly journal Taiwan kyōiku  (Taiwan education), which was read by teachers and students. He was the most important art educator in Taiwan at that time. In the July 1929 issue of the Taiwan jihō he published a long essay on art and culture, “Kumpūta

(Taiwan education), which was read by teachers and students. He was the most important art educator in Taiwan at that time. In the July 1929 issue of the Taiwan jihō he published a long essay on art and culture, “Kumpūta  ” (The south chair), that centered mainly on the theme of mild nostalgia that develops out of patriotic sentiment. He expressed the thought that Taiwan’s natural and human environments lacked an intrinsic flavor and had no distinguished, lingering charm—there was only a bright, hard, coarse quality, no feeling of mysterious loneliness.16 In contrast to Japan’s delicate, stylish culture, Taiwan’s culture was coarse, monotonous, and naïve; contrasted with Japan’s subdued, gentle landscape, Taiwan’s landscape was bright, majestic, and hard.

” (The south chair), that centered mainly on the theme of mild nostalgia that develops out of patriotic sentiment. He expressed the thought that Taiwan’s natural and human environments lacked an intrinsic flavor and had no distinguished, lingering charm—there was only a bright, hard, coarse quality, no feeling of mysterious loneliness.16 In contrast to Japan’s delicate, stylish culture, Taiwan’s culture was coarse, monotonous, and naïve; contrasted with Japan’s subdued, gentle landscape, Taiwan’s landscape was bright, majestic, and hard.

Because Ishikawa’s role changed during his second Taiwan sojourn to that of an art teacher, he dealt with students who were extremely eager to learn, and he was warmly welcomed and revered by them. However, his knowledge of Taiwan seemed to remain stuck at the level of drawing superficial, impressionistic comparisons, especially with regard to light and color. In fact, because he usually did not date the large quantity of Taiwanese landscapes that he finished during the seventeen years he stayed in Taiwan, we always have to rely on changes in his signature or the appearance of newly constructed buildings in his pictures to arrive at approximate dates for his paintings. It is not easy to judge the dates based on his stylistic development or his interpretation of the landscape.

As we re-read Ishikawa’s “The South Chair,” we see that Japan is always the subjective reference point for his cultural perspective, and that Taiwan functions only occasionally as an objective contrast. He begins his essay:

As a balmy breeze blows, I sit on my chair, meditating on stylistic perspectives, which is also very much a cooling pleasure. The first question I think about is, does Taiwan really have that kind of stylistic perspective we think of? Thus, it’s necessary to first study and examine the so-called Japanese stylistic perspective.

He then introduces in some detail the formation of Higashiyama culture during the Muromachi period (1333–1568), including the tea ceremony, nō drama, literature, and art. He infers that Taiwan has no similar stylistic perspective. Although his essay is subtitled “Taiwan’s stylistic perspective,” he discusses Japanese styles or attitudes toward artistic appreciation only from the Muromachi period to the Edo period. We can well imagine that searching for signs of Muromachi aristocratic culture in Taiwan during the early colonial period was no different than searching for fish in a tree. However, this prompts us to consider a more worthwhile question: what is the deeper meaning to what he considered was the stylish, elegant cultural perspective of the Japanese people?

THE LANDSCAPE OF JAPAN AND TAIWAN

In 1931, another famous watercolorist, Maruyama Banka  (1867–1942), Ishikawa’s friend, spent nearly two months traveling in Taiwan. He exhibited the works that he painted at the sites he visited and lectured in Taipei on what he had seen and heard.17 Like Ishikawa, Maruyama was fond of categorizing landscapes, and he also thought that the acacia was Taiwan’s most noble tree.

(1867–1942), Ishikawa’s friend, spent nearly two months traveling in Taiwan. He exhibited the works that he painted at the sites he visited and lectured in Taipei on what he had seen and heard.17 Like Ishikawa, Maruyama was fond of categorizing landscapes, and he also thought that the acacia was Taiwan’s most noble tree.

His impressionistic categorizations of Taiwan’s rural and natural scenes not only follow Ishikawa’s but can also be traced further back to an 1894 work that influenced the aesthetic views of both artists, The Landscape of Japan (Nihon fūkeiron  ) by Shiga Shigetaka

) by Shiga Shigetaka  (1863–1927).18 A cultural-geographical treatise, the book presents a lively description of Japan’s landscape. By describing the landscape as a heaven on earth, it promoted a highly patriotic viewpoint. Shiga identified three particular characteristics of the Japanese landscape: elegance, beauty, and boldness. This emphasis on literary elegance is echoed in Ishikawa’s “The South Chair” when he extols the stylistic elegance of Japan’s Muromachi period. Even though Ishikawa’s argument might not come directly from Shiga Shigetaka, the two probably have a common source, and Shiga’s theories had circulated widely in Japanese intellectual circles for many years.

(1863–1927).18 A cultural-geographical treatise, the book presents a lively description of Japan’s landscape. By describing the landscape as a heaven on earth, it promoted a highly patriotic viewpoint. Shiga identified three particular characteristics of the Japanese landscape: elegance, beauty, and boldness. This emphasis on literary elegance is echoed in Ishikawa’s “The South Chair” when he extols the stylistic elegance of Japan’s Muromachi period. Even though Ishikawa’s argument might not come directly from Shiga Shigetaka, the two probably have a common source, and Shiga’s theories had circulated widely in Japanese intellectual circles for many years.

Shiga encouraged Japan’s geographers to go out and research the geography of all continental Asia. He wrote:

Japan is a “forerunner country” for Asia, and Asian cultural development is a natural occupation for the Japanese. Therefore, while Europe’s geographers have not yet fully researched the geography of continental Asia, Japan’s geographers should work to do so. … This will help establish a lasting reputation for Japan’s natural sciences.19

Under this “Great Japan” mindset, Mount Fuji became the standard for famous mountains. Shiga suggested that Taiwan’s highest mountain, Mount Jade, be renamed “Taiwan’s Fuji.” Likewise, Mount Tai in Shandong province could be renamed “Shandong’s Fuji.”20

While Shiga elevated Japan’s pine trees, Ishikawa chose Taiwan’s acacias as a conventional representative of the landscape.21 Landscape of Japan also encouraged an enthusiasm for mountain climbing among Japan’s watercolorists, which accounts for the appearance of “mountain painters” (sangaku gaka  ). They formed groups to study Japan’s landscape and local folkways. Thus, when the elderly Maruyama Banka went to Taiwan, he headed directly to Alishan, where he investigated the climate and flora. Based on this first impression of Taiwan’s landscape, he categorized Taiwan as a sweet potato-shaped island with a north-south central mountain range that looks like the background of a painting when viewed from the western shore: “In the foreground [of the painting] is an acacia grove, or just one or two acacias, or perhaps a small hill covered with acacias. Matching this in the background is the central mountain range. Water buffaloes function to decorate the scene.”22 This kind of simple, formulaic view-finding, coupled with a poetic vision, is similar to the aesthetic structuring methods used by Shiga Shigetaka to categorize the Japanese landscape.23 Despite the brevity of such descriptions, they are full of romanticism and nostalgia.

). They formed groups to study Japan’s landscape and local folkways. Thus, when the elderly Maruyama Banka went to Taiwan, he headed directly to Alishan, where he investigated the climate and flora. Based on this first impression of Taiwan’s landscape, he categorized Taiwan as a sweet potato-shaped island with a north-south central mountain range that looks like the background of a painting when viewed from the western shore: “In the foreground [of the painting] is an acacia grove, or just one or two acacias, or perhaps a small hill covered with acacias. Matching this in the background is the central mountain range. Water buffaloes function to decorate the scene.”22 This kind of simple, formulaic view-finding, coupled with a poetic vision, is similar to the aesthetic structuring methods used by Shiga Shigetaka to categorize the Japanese landscape.23 Despite the brevity of such descriptions, they are full of romanticism and nostalgia.

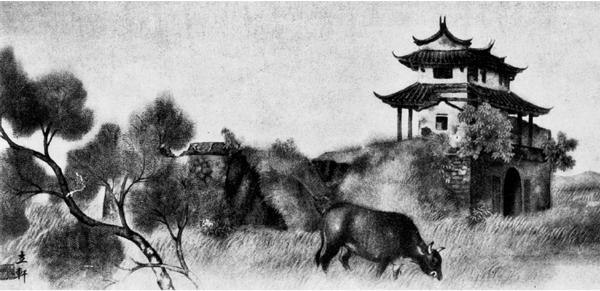

This kind of nostalgic sentiment may be said to represent Ishikawa’s main theme in his depictions of Taiwanese landscapes. Among his Taiwanese landscape paintings, we find many that depict acacia trees (fig. 11.2: Taiwan Street), and many others that seek to express a nostalgic mood through the depiction of old buildings, such as Old City, painted around 1910. The pavilion-like structure in this painting is Taipei’s Little South Gate (Hsiao-nan-men), which remains from the Ch’ing dynasty city wall. Later in his career Ishikawa repeatedly depicted Little South Gate from memory, even though the scene had long since changed, as in 1932’s South Gate Street (fig. 11.3). In his earlier Old City, the detail in the clouds, the broad, low horizon, and the majestic height of the trees clearly reflect the influence of nineteenth-century English landscape painting.

FIGURE 11.2 Ishikawa Kinichirō, Taiwan Street, undated.

FIGURE 11.3 Ishikawa Kinichirō, South Gate Street, 1932.

With all this as background, we can better understand how Ishikawa came to define Japanese stylistic elegance via a blend of Muromachi period literature and artistic tradition. Meanwhile, under the rising influence of patriotism from the beginning of the Meiji era, he considered Japanese aesthetics as the highest expression of East Asian civilization. Due to the impact of Shiga’s Landscape of Japan, Ishikawa could not avoid using “Japan’s three most beautiful sights” as standards for all other landscapes, or for considering the coast of the Seto Inland Sea as the most beautiful in the world.24 Perhaps the same kind of Meiji era nationalism that led him to join the eight allied forces in China also accompanied him after he went to Taiwan’s mountains and portrayed the governor-general’s invasions there.

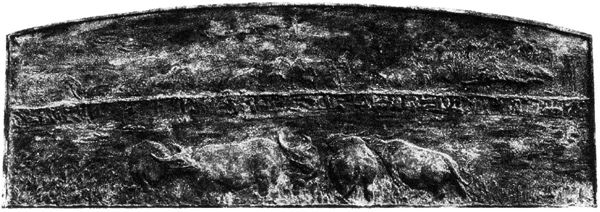

We cannot overlook the lasting influence that the rural landscapes promoted by Ishikawa and other watercolorists had on the first phase of modern Taiwanese art. The influence was not limited to the students who studied directly under him but extended to all who formed their earliest artistic perspectives by reading his many articles. We cannot help but recall that Huang T’u-shui  , the first-generation Taiwanese sculptor active during the 1920s, also understood the Taiwanese landscape through the filter of a kind of rural romanticism (fig. 11.4).25

, the first-generation Taiwanese sculptor active during the 1920s, also understood the Taiwanese landscape through the filter of a kind of rural romanticism (fig. 11.4).25

If we look at the list of works shown in the first three Taiwan Art Exhibitions (Taiwan bijutsu teurankai  ; 1927–1929), we find that acacia trees were a very popular subject, especially in rural scenes, where their gently curving branches often appear at the foot of mountains or along roadsides. In the Oriental painting (Tōyō ga

; 1927–1929), we find that acacia trees were a very popular subject, especially in rural scenes, where their gently curving branches often appear at the foot of mountains or along roadsides. In the Oriental painting (Tōyō ga  ) category of the exhibitions, artists like Lin Yü-shan

) category of the exhibitions, artists like Lin Yü-shan  (b. 1907; Large Southern Gate, 1927, fig. 11.5) and Kishita Seigai

(b. 1907; Large Southern Gate, 1927, fig. 11.5) and Kishita Seigai

(1887–1988; Wind and Rain, 1927, fig. 11.6) paid very close attention to the forms of acacia trees. As for the Western painting (Seiyō ga

(1887–1988; Wind and Rain, 1927, fig. 11.6) paid very close attention to the forms of acacia trees. As for the Western painting (Seiyō ga  ) category, many paintings by Ishikawa’s students were admitted, such as Su Hsin-i’s To the Three Gorges (1928; fig. 11.7).

) category, many paintings by Ishikawa’s students were admitted, such as Su Hsin-i’s To the Three Gorges (1928; fig. 11.7).

FIGURE 11.4 Huang T’u-shui, Landscape of the South, relief, 1927.

FIGURE 11.5 Lin Yü-shan, Large Southern Gate, 1927.

FIGURE 11.6 Kishita Seigai, Wind and Rain, 1927.

FIGURE 11.7 Su Hsin-I, To the Three Gorges, 1928.

WATERCOLOR PAINTING AND TRENDS IN CONTEMPORARY ART

Ishikawa’s promotion of watercolor painting in Taiwan was an extension of the early-twentieth-century popularity of modern Western art in Japan, and Taiwan in the 1920s was an excellent place for him to establish watercolor painting.26 Of course, he succeeded in cultivating many amateur artists. As for Ishikawa himself, though, he gradually lost touch with the mainstream trends of Western-style art in Japan, including the academic school, after he spent so many years in Taiwan—not due to the geographic distance so much as the rapidity of change in Japanese artistic trends. More important, with the opening of the Taiwan Art Exhibition in 1927, more and more professionally trained artists appeared. These included Taiwanese and Japanese students who had received training in the Tokyo School of Fine Art and eminent Japanese artists who had been invited to come to Taiwan as judges for the art exhibitions. As these artists enriched the Taiwanese art scene, watercolor painting gradually faded from the mainstream, and Ishikawa’s influence waned quickly.

Furthermore, the other Japanese judge of Western-style exhibition painting, Shiotsuki Tōhō  (1885–1954), specially addressed the issue of watercolor painting in his brief judge’s statement after the exhibition in 1927:

(1885–1954), specially addressed the issue of watercolor painting in his brief judge’s statement after the exhibition in 1927:

Watercolor painting, which is more prone to technical constraints than oil painting, can easily fall into the old pattern of following prior masters’ methods. I hope that watercolorists deeply reflect on this. If they forget to explore their own unique realm, then their painting stops at the level of mere work.27

Shiotsuki’s brief warning cut deep. By the 1930s, his distinctive style and influence had formed a counterbalance to that of Ishikawa, replaced it, and become another force—which will be the subject of another essay. In short, at the sixth Taiwan Art Exhibition in October 1932, only one watercolor painting was included, Lan Ying-ting  ’s Commercial Lane (fig. 11.8). Lan was considered Ishikawa’s handpicked successor, but after this year he withdrew from the competition.

’s Commercial Lane (fig. 11.8). Lan was considered Ishikawa’s handpicked successor, but after this year he withdrew from the competition.

FIGURE 11.8 Lan Ying-ting, Commercial Lane, 1932.

As for the Taiwan Watercolor Society, founded under the guidance of Ishikawa in 1926, it faced a serious trial in 1931, due to the storm caused by the exhibition in Taipei of Fauvist and surrealist paintings by artists of the Dokuritsu Bijutsukyōkai  (Association of Independent Artists) from Tokyo: one after another member abandoned watercolor and joined the new schools of painting. At the summer art seminars of the Dokuritsu Bijutsukyōkai in Taipei, more and more younger Taiwanese and Japanese artists who had been born in Taiwan were in attendance.28 From this time onward, watercolor painting was no longer part of the Taiwanese artistic mainstream, just as rural cowherd romanticism had also faded. The artists of the younger generations would have a much broader subject matter and much brighter prospects to confront in their individual works.

(Association of Independent Artists) from Tokyo: one after another member abandoned watercolor and joined the new schools of painting. At the summer art seminars of the Dokuritsu Bijutsukyōkai in Taipei, more and more younger Taiwanese and Japanese artists who had been born in Taiwan were in attendance.28 From this time onward, watercolor painting was no longer part of the Taiwanese artistic mainstream, just as rural cowherd romanticism had also faded. The artists of the younger generations would have a much broader subject matter and much brighter prospects to confront in their individual works.

NOTES

1. “Onshi Ishikawa Kinichirō sensei [Our beloved teacher, Mr. Ishikawa Kinichirō],” Taiwan kyōiku  [Taiwan education] 412 (Nov. 1936), 71–74.

[Taiwan education] 412 (Nov. 1936), 71–74.

2. Ishikawa Kinichirō, “Taiwan hōmen no fūkei kanshō ni tsuite,” Taiwan jihō  [Taiwan review] (March 1926), 53.

[Taiwan review] (March 1926), 53.

3. Ishikawa Kinichirō, “Taiwan no sansui,” Taiwan jihō (July 1932), 110–116.

4. Ishikawa Kinichirō, “Taiwan fūkō no kaisō [Recollections of Taiwan’s scenery],” Taiwan jihō (June 1935), 53.

5. Tachibana Gishō, “Ishikawa Kinichirō—aru Meiji seishin no dansei to sono shūen [Ishikawa Kinichirō: The birth of a certain Meiji spirit and its final moment],” in Shizuoka no bijutsu V—Ishikawa Kinichirō ten  [Fine Arts of Shizuoka V—Exhibition of Ishikawa Kinichirō] (Shizuoka: Shizuoka Prefectural Museum of Fine Art, 1992), 10.

[Fine Arts of Shizuoka V—Exhibition of Ishikawa Kinichirō] (Shizuoka: Shizuoka Prefectural Museum of Fine Art, 1992), 10.

6. Ishikawa, “Suisaiga to Taiwan fūkō [Watercolor painting and Taiwan’s scenery],” Taiwan nichinichi shinpō  [Taiwan daily news], Jan. 23, 1908.

[Taiwan daily news], Jan. 23, 1908.

7. Ishikawa, “Tattaka no omode [Recollections of Tattaka],” Taiwan jihō (November 1929), 124.

8. “Ishikawa Kinichirō nempu [Chronology of Ishikawa Kinichirō],” in Shizuoka no bijutsu V—Ishikawa Kinichirō ten, 168–169; Lin Ju-wei, “Shih-ch’uan Ch’in-i-lang ti-i-tz’u tsai T’ai-wan te huo-tung [Ishikawa Kinichirō’s activities during his first sojourn in Taiwan],” I-shu-chai [The artist], June 1995, 350–360.

9. Ishikawa, “Suisaiga to Taiwan fūkō.”

10. Fujii Shitsue, Li fan—Jih-pen chih-li T’ai-wan te chi-ts’e [Civilizing the barbarians: Japan’s policy in governing Taiwan] (Taipei: Wen-ying-t’ang, 1997), 209.

11. “Hakubutsukan no itsu isai (Kitashirakawa go dassen no hengaku) [A conspicuous addition to the museum (Prince Kitashirakawa’s battleground picture)],” Taiwan nichinichi shinpō, March 8, 1909, 5; Ishikawa, “Nōkyū shinnō tenshita Hakkeyama sensō yuga kinsaku ni tsuite [Regarding the respectfully composed oil painting of His Majesty Prince Nōkyū at the Mount Pakua Battle],” in Taiwan Hakubutsukan kyōkai, Sōritsu sanjū nen kinen ronbunshū [Essays on the thirtieth anniversary of the Taipei museum’s founding] (Taipei: Hakubutsukan, 1939).

12. Ishikawa, “Tatsutaka no omode.”

13. “Nantō bankai shaseiga no kenjō [Presentation of paintings of the barbarian regions],” Taiwan nichinichi shinpō, July 24, 1909, 2; “Eikan no seiban shasaiga (Ishikawa Kin’ichirō shi no kōei) [Imperial approval of the paintings of untamed barbarians (Mr. Ishikawa Kin’ichirō’s honor)],” Taiwan nichinichi shinpō, Aug. 29, 1909, 6.

14. Nakasono Hidesuke, Niao-chü Lung-tsang—ts’ung-heng T’ai-wan yü Tung-ya te jenlei-hsüeh hsien-ch’ü [Torii Ryūzō: Pioneering anthropologist who covered Taiwan and East Asia], trans. Yang Nan-ch’ün (Taichung: Hsing-chen, 1998).

15. See Miyaoka Maoko, “Yajin no bunka jinruigaku [Rustics’ cultural anthropology],” in Nanpō bunka 24 (Nov. 1997), 123–137; Mori Ushinosuke, T’ai-wan hsing-chiao—Sen Ch’ouchih-chu te T’ai-wan t’an-hsien [Taiwan tracks: Mori Ushinosuke’s Taiwanese expeditions], trans. Yang Nan-ch’ün (Taipei: Yuan-liu, 2000), 26.

16. Ishikawa, “Kumpūta [The south chair],” Taiwan jihō (July 1929), 50–55.

17. Maruyama Banka, “Watashi no moku ni Taiwan fūkei [Taiwanese landscapes I have seen],” Taiwan jihō (August 1931), 32–42.

18. This book was so widely read that by June 1903 it was already in its fifteenth printing, and had been expanded with each reprinting.

19. Shige, Nihon fūkeiron, 326.

20. Shige, Nihon fūkeiron, 320, 329.

21. Ishikawa, “Suisaiga to Taiwan fūkō.”

22. Maruyama, “Watashi no moku ni Taiwan fūkei”; Yen Chuan-ying, T’ai-wan chin-tai mei-shu ta-shih nien-piao, 115–116.

23. Shiga, Nihon fūkeiron, 17.

24. The “Three Famous Scenes” in Japan are Matsushima  , Amanohashidate

, Amanohashidate  , and Itsukushima

, and Itsukushima  , all of which are famous for their pine trees. For descriptions of these three places and the Seto Inland Sea, see Maruyama, “Watashi no moku ni Taiwan fūkei,” and Ishikawa, “Kumpūta.”

, all of which are famous for their pine trees. For descriptions of these three places and the Seto Inland Sea, see Maruyama, “Watashi no moku ni Taiwan fūkei,” and Ishikawa, “Kumpūta.”

25. For a discussion of Huang T’u-shui’s rural style, see Yen Chuan-ying, “P’ai-huai tsai hsien-tai i-shu yü min-tsu i-shih chih chien—T’ai-wan chin-tai mei-shu-shih hsien-ch’ü Huang T’u-shui [Wandering between modern art and ethnic consciousness: Huang T’u-shui, a forerunner of Taiwan’s modern art history],” in Yen, ed., T’ai-wan chin-tai mei-shu ta-shih nien-piao, xvii–xxiii.

26. Nakamura Giichi, “Nihon kindai bijutsushi ni okeru Taiwan—Ishikawa Kinichirō to Shiotsuki Tōhō [Taiwan in modern Japanese art history: Ishikawa Kinichirō and Shiotsuki Tōhō],” in Shizuoka no bijutsu V—Ishikawa Kinichirō ten, 24.

27. Shiotsuki Tōhō, “T’ai-chan yang-hua kai-p’ing,” trans. Wang Shu-chin, in Taiwan jihō (November 1927), 21–22.

28. About the activities of Taiwan’s newly developed arts groups, see Yen Chuan-ying, “Jihchih shih-tai mei-shu hou-ch’i te fen-lieh yü chieh-shu [Divisions and endings in art during the late period of Japanese rule],” in Ho wei T’ai-wan, 17–18.