Ethnicity, Violence, and Wartime Mobilization in Colonial Taiwan

In the fall of 1945—after the announcement of Japan’s surrender to the Allied Forces but prior to the formal takeover of Taiwan—some two or three hundred incidents of assault and theft in Taiwan were reported by the colonial police bureau.1 Although contemporary newspapers, as well as latter-day memoirs and oral histories, briefly mention these incidents, few historians have given them much attention.

Contemporary and historical accounts provide various explanations for this unlawful activity. A leaflet distributed in September 1945 in mid-Taiwan (with the intent of curtailing this activity) stated:

Ignorant and stupid brothers, watching for the chance to commit wrongs and taking advantage of circumstances to act like brutes, have disrupted social order, encroached upon personal liberty, and damaged public construction materiel.2

In contrast, a November 1945 police bureau report that targeted areas for immediate attention inferred that postsurrender violence and plunder had been instigated by suppressed bandits who had reemerged in 1945 to incite the culturally deprived populace to commit crimes against the state.3 More recent explanations, on the other hand, tend to favor circumstantial (e.g., a political vacuum) or Nationalistic (e.g., anti-Japanese sentiment) explanations.4 This essay offers an alternative theory.

In this version of my analysis of this postsurrender behavior, I am concerned with the following issues. First, should we agree with the pundits and some post-colonialists that historians have no direct access to the motives and explanations of these acts of violence and incidents of plunder? Second, for those who recall the colonial period and its “lawful society” with nostalgia, how can these incidents of assault and theft, numbering in the hundreds, be understood? Will this evidence suggest that colonial-era law and order was but a myth? Or can we better understand this modernist rhetoric through a rigorous analysis of irregular data? Finally, how does one assess the state’s evidence without internalizing (or adopting temporarily) the state’s discourse and perspective? Are these immediate post-surrender actions really “crimes against the state”? Will this official data reveal what is powerful about the myth of political vacuums?

CONFLICT AND THEFTS: THE STATISTICS

The data on “violence” and “plunder” cited here was presented in quantitative form when it was first reported by the Taiwanese colonial police authorities in the fall of 1945, and it was the quantitative aspect of the documents that first caught my interest.5 Since 1993, when I first encountered this data on postsurrender violence and theft, I have analyzed the police reports (with supplementary tables and maps) intensively on two occasions, and in both instances the quantitative data obtained from these sources has been the primary focus of my effort and attention. I suspect there is something soothing about the knowledge that comes to us (from a source such as the police bureau) in the form of numbers. Like other “facts” (such as dates), numerical data may invite our interpretation, but we often expect that the analytical process will be relatively transparent, unlike our readings of textual information. Even the best of us question this assumption very seldom.

Thus, I begin my analysis here by looking at the quantitative data and my first-level manipulation of it. In fact, not much manipulation was really required. The brief tabular data of violence against police officers, and against public officials (excepting police officers), and incidents of mass plunder required more translation—then to now, Japanese to English—than manipulation. Dates, place-names, numbers of perpetrators, etc., were already distinguished from one another and arranged in chronological fashion in the tables. The visual presentation of violent action and thefts on the map required a “symbol-to-text” translation that was also rather straightforward.6 Even the narrative description and analysis of “hotspots” in the November 1945 police report had more information presented in tabular form than one expects to find in most documents.7

I also suspect that my first-level manipulation was governed by general disciplinary training—social history or maybe social science. Along with the police investigator, I expected that distinguishing the ethnicity of the victim, the locations of the violent (or plundering) incidents over time, or the relative numbers of perpetrators might explain these acts of human violence and theft. In addition to these correlations, I hoped to learn something from a basic chronological analysis (for example, whether events can be seen to occur in clumps, in peaks, or according to some sort of rhythm). And from the supplementary data in the tables—more interpretative in nature—I could at least compile a general listing of stated causes and police responses or compare the types and numbers of public officials involved in these conflicts. I was hoping that these first-hand annotations and speculations were as accurate as any that we latecomers could imagine. I have completed each of these manipulations more than once and discuss my results immediately below.

Finally, like any trained historian, I also expected that careful attention to mistaken calculations or conflicting figures would provide some critical distance from the numbers, whatever their reliability quotient might be. Thus, when I found three different sets of regional analyses, I compared them, though without obtaining any immediate revelations.

INITIAL INSIGHT FROM STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Regional Analysis

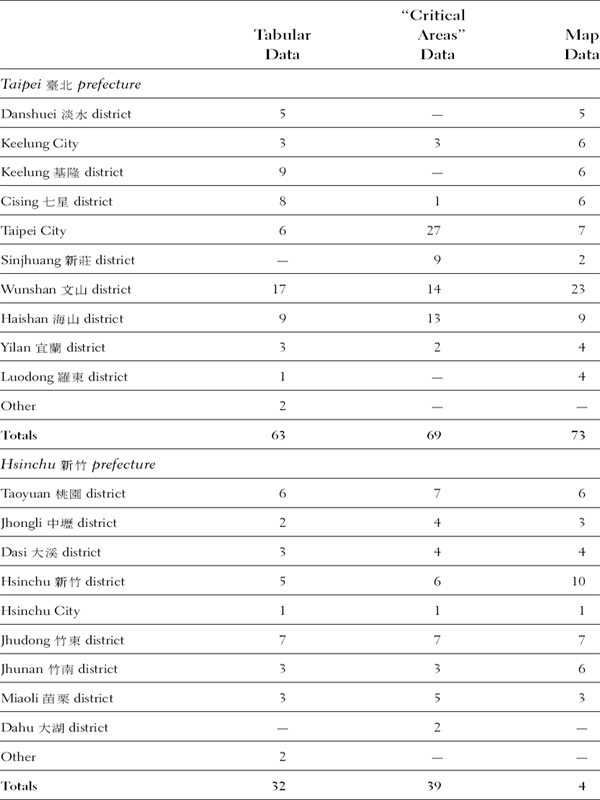

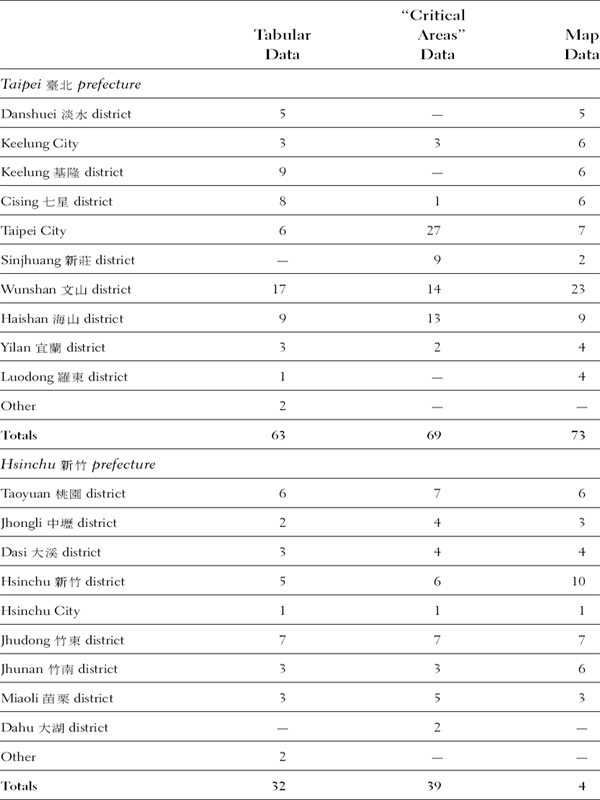

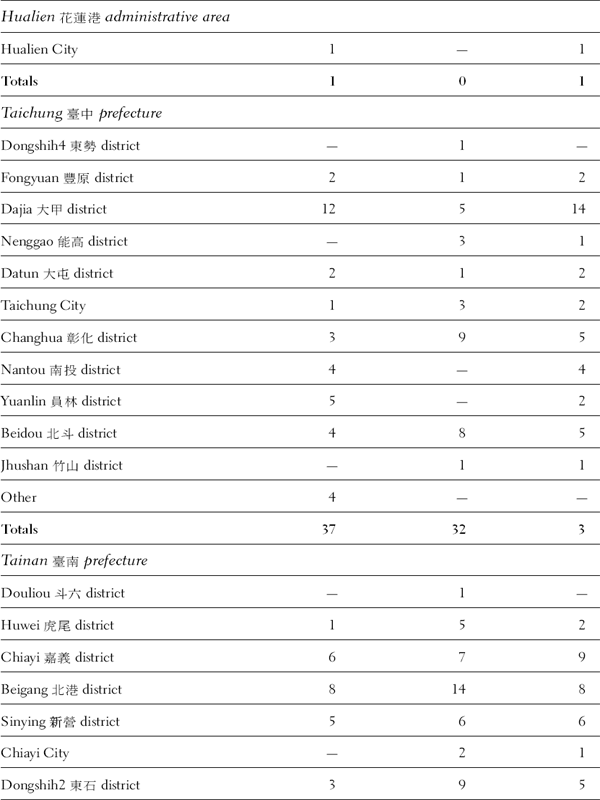

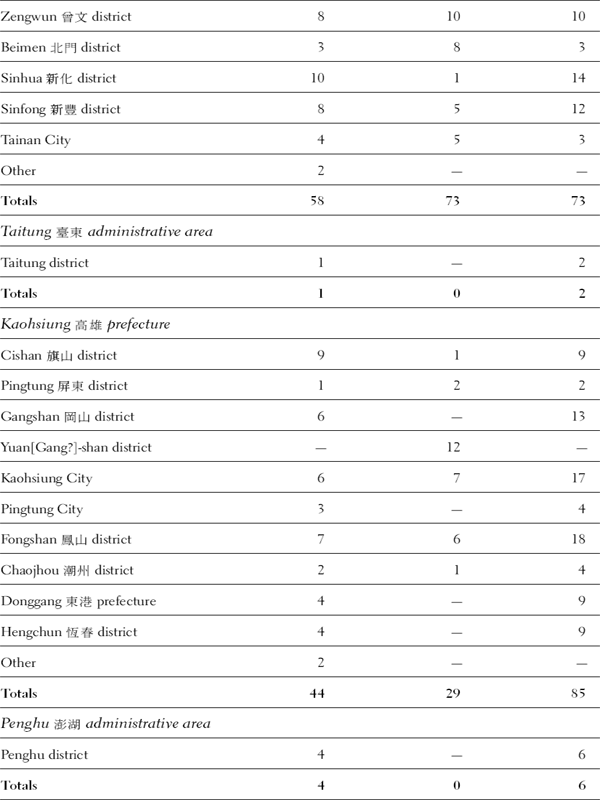

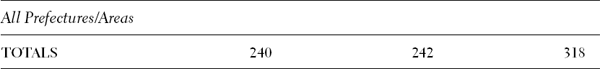

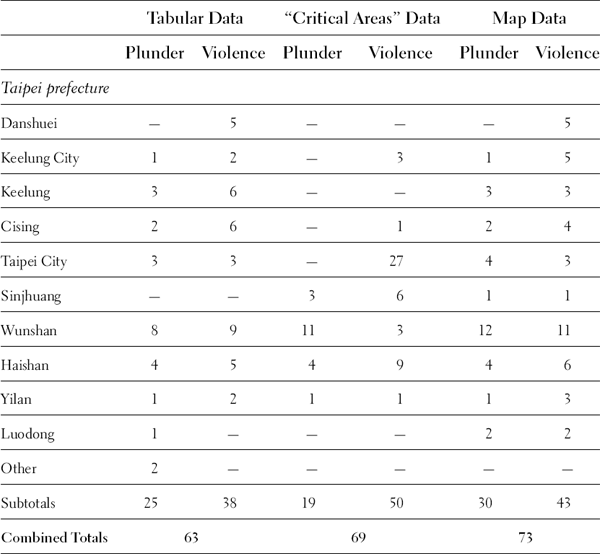

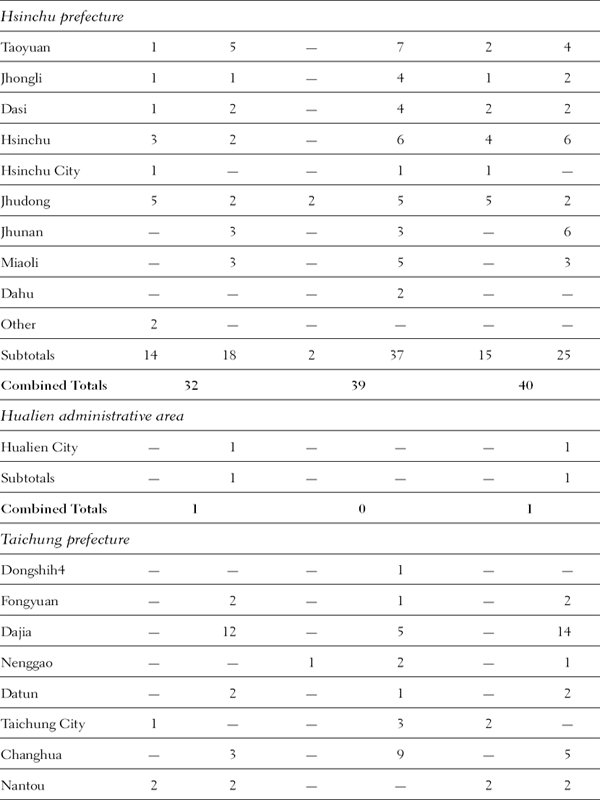

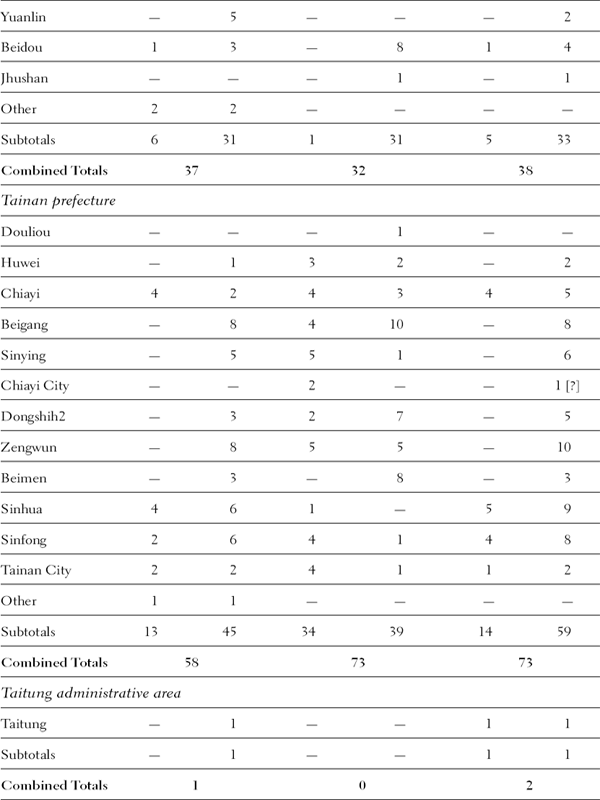

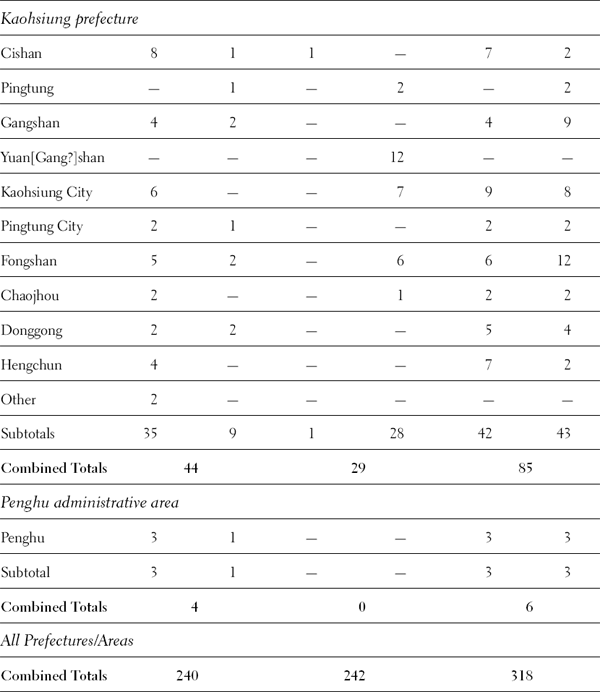

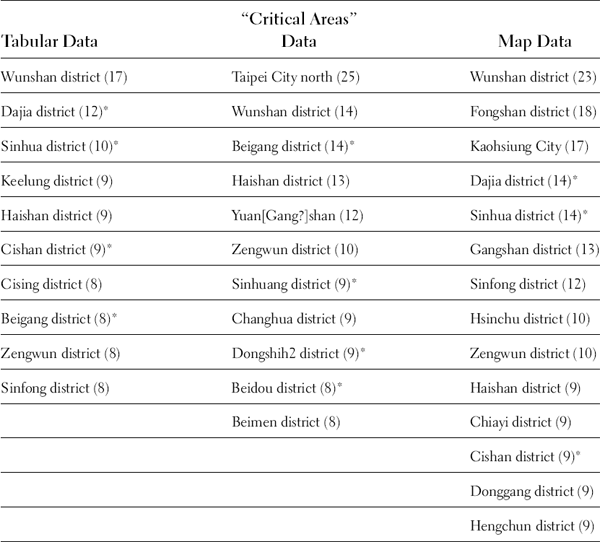

The three sources of regional information (i.e., tabular data, “critical areas,” and map) provide different data, perhaps because they are the results of three different “snapshots” of social (dis)order (see tables 16.1 and 16.2). Tainan prefecture rates high (in absolute numbers of incidents of violence and theft) in all three data sets, while Taipei and Kaohsiung prefectures score highest on the tabular and map data sets, respectively. With respect to incidents of disorder in single districts, Wunshan district (in Taipei prefecture) rated high in all three data sets. Dajia (in Taichung prefecture), Sinhua (in Tainan prefecture), and Gangshan (in Kaohsiung prefecture) registered high numbers of incidents in at least two of the data samples. One might conclude, then, that these areas revealed a relatively greater amount of social disorder in these months immediately after surrender.

If these statistics are reliable, then one might ask what is unusual about these particular areas of the island. This question occupied the police bureau analyst who compiled the report entitled “Information on critical areas of activities,” which I’ll discuss below.8 On the other hand, after exploring the disorder recorded in the tabular data,9 I find it clear that in some instances the reporting authority gave “incident” status to (what seem to be) individual segments of a larger “event.” Although a reconstitution and subsequent recalculation of the data may lower the scores of certain districts, I don’t suspect that this will change the overall results significantly. The question stands: “Why did more incidents of violence and theft occur in some areas than in others?”

TABLE 16.1 Total Incidents of Violence and Plunder, Regional Analysis: Comparison of Three Sources of Information

Sources:

Tabular data: [Taiwan Kempeitai Shireibu], “Funjō boppatsu o yosō shieru chi-iki ni okeru jōhō,” [October 1945].

“Critical areas”: Taiwan Sōtokufu, Keimukyoku, “Sōjō boppatsu no kanōsei aru chi-iki ni kan suru jōhō,” November 1945.

Map: [Taiwan Kempeitai Shireibu], “Kiō no hassei jiken yori nitaru funjō boppatsu kanōsei chi-iki gaikenzu,” [October 1945].

TABLE 16.2 Incidents of Violence and Plunder, Regional Analysis: Comparison of Three Sources of Information

Sources:

Tabular data: [Taiwan Kempeitai Shireibu], “Funjō boppatsu o yosō shieru chi-iki ni okeru jōhō,” [October 1945].

“Critical areas”: Taiwan Sōtokufu, Keimukyoku, “Sōjō boppatsu no kanōsei aru chi-iki ni kan suru jōhō,” November 1945.

Map: [Taiwan Kempeitai Shireibu], “Kiō no hassei jiken yori nitaru funjō boppatsu kanōsei chi-iki gaikenzu,” [October 1945].

There are also some startling numbers in each of the data sets that require some explanation. For instance, in the “critical areas” data (see table 16.2), the authorities recorded twenty-five incidents of violence against public officials in Taipei City north.10 That number exceeds the total amount of disorder for any other city or district in the data samples (see table 16.1). Although this figure is not consistent with the map data for Taipei City (which may reflect more complete regional reporting) or the tabular data, I can find no reason to discard it without some explanation (though I do want to register some tentative suspicion). However, even if this figure for Taipei City north in the “critical areas” report is a clerical error, the same cannot be said for Tainan prefecture. In all three data samples, Tainan ranks first (or second in the “critical areas” data if Taipei City north figures are accurate) in incidents of violence committed against officials and police officers. Why would either region be so prone to violence against public officials? The statistics themselves provide us with no immediate answer; for that we will have to turn to other sources.

Finally, another figure that requires some explanation is the number recorded for collective plunder in Kaohsiung prefecture in two data sets (see table 16.2). I suspect that these unusual numbers of incidents (35 and 42) may simply reflect the concentration of military facilities in this southern prefecture rather than any “southern Taiwanese” predilection for collective plunder.

Chronological Analysis

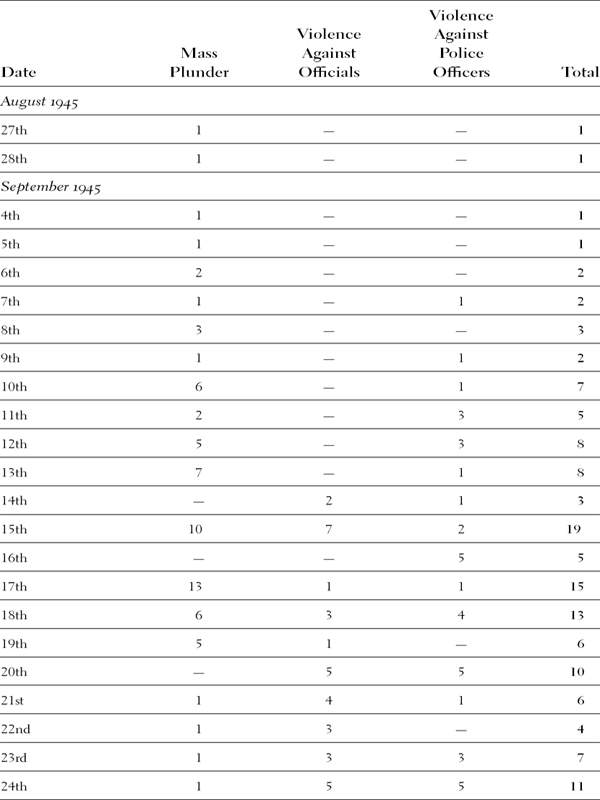

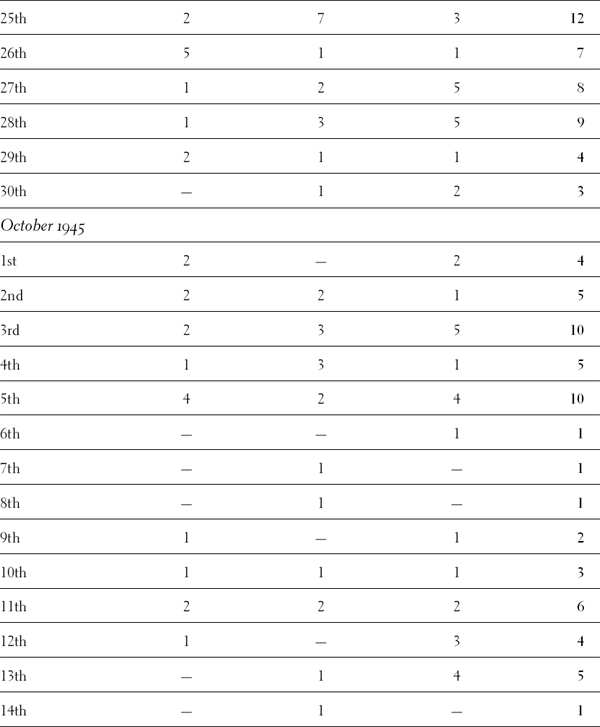

Unfortunately, my efforts to discover some pattern in the temporal arrangement of the incidents of disorder provided me with very few insights (see table 16.3). In part, the data for violent attacks begins later than the information on thefts. In addition, the fluctuation in number of incidents from day to day during the peaks of social disorder are quite difficult to interpret. One overall impression is clear: mid-September was a difficult period of time for those in law enforcement. On September 15, nineteen incidents of mass plunder and assaults upon police and public officials were reported by the colonial law enforcement authorities, and figures for September 17 and 18 are also unusually high. A second peak was experienced about ten days later (on the 24th and 25th), and the early days of October were relatively unstable. All other periods pale in comparison.

However, I suggest that we treat these numbers with some caution. The total number of nineteen incidents recorded on September 15 is not, in retrospect, surprising to me (though I wish I had data on the incidence of social conflicts for tense periods during 1941–1945 with which to compare these late 1945 figures). Ten attempts to steal military provisions, together with seven attacks on public officials and two incidents of violence against patrolmen, do not comprise an island-wide movement to overthrow the colonial government. Furthermore, although total incidents for September 17 and 18 are comparatively high, (attempted) thefts of military provisions seem to account for these peaks; violence against officials and the police rose later in the month (on the 20th, 24th, and 25th). In all honesty, I suspect that the chronological analysis merely tells us that it took about a month for the authority of the colonial police force to wear thin. However, these figures also support my contention that as late as the middle of October (before any of Chen Yi’s troops had arrived), the colonial government was still in control.

TABLE 16.3 Chronological Analysis of Incidents of Violence and Plunder

Source: [Taiwan Kempeitai Shireibu], “Funjō boppatsu o yosō shieru chi-iki ni okeru jōhō,” [October 1945].

Having made those very general claims, though, I want to register some skepticism with these explanations. All data is limited, and this chronological data is no exception. One hopes that limited data can still tell us something about change over time. While change in this case may merely be that associated with administrative stability and control capabilities (i.e., the degree to which local police stations are able to record and respond to acts of civil disorder), change might also be found in the incidence of civilian resistance against the colonial regime. Similar events, or shifts in civilian (or official) attitudes, may have had an impact on both types of change. However, at this point in my research I cannot yet pinpoint the specific (potential) events in the mid- and late September history of immediate postsurrender Taiwan that would give me a clearer explanation for the trends I see in this chronological analysis of civilian disorder.11

Perpetrator Numbers

Most of my in-depth quantitative analysis in this paper is based on the textual record of immediate postsurrender conflict compiled by the military police in mid-October—what I have called the data set in tabular form, or “tabular data.”12 Although this source is relatively precise when recording the ethnicity and number of victims, it is less accurate in regard to incident perpetrators. For example, fewer than one-third of the ninety-six incidents of collective theft (or “mass plunder”) give precise information on the number of perpetrators (see table 16.4). The term “villagers” is employed for fifty-two of these incidents, and no information is given for an additional seventeen cases.13 Reports on violent attacks are relatively more useful in this regard, but a substantial number of these records employ the term “several” or “many” rather than specifying the exact number of people involved. One can hardly blame the compiler for this flaw in the data. I mention it here merely to call attention to the uneven quality of the information being analyzed.

What do we learn from the statistics on perpetrators? First of all, it appears that a substantial number of the violent encounters were initiated by individuals or small groups. More than one-half of the violent attacks on public officials were committed by single individuals or groups of individuals fewer than five. If “several” refers to more than three and fewer than ten individuals, then attacks on policemen reveal the same type of pattern. I suspect that this is also true for the thefts of military provisions. However, one cannot end discussion here. The tabular data clearly states that twenty-four of these events (nine cases of mass plunder, nine instances of violence against public officials, and six attacks on police officers) involved a crowd of more than one hundred people. Within the history of social grievance in Taiwan, whether colonial or postwar periods, this level of large-scale action is astounding.

TABLE 16.4 Analysis of Numbers of Perpetrators

Source: [Taiwan Kempeitai Shireibu], “Funjō boppatsu o yosō shieru chi-iki ni okeru jōhō,” [October 1945].

In order to understand these large-scale incidents as an extraordinary type of collective theft or violent attack, I looked for patterns among the twenty-four instances of crowd behavior. First of all, regional concentration was readily apparent: nine cases occurred in Kaohsiung prefecture, while ten others erupted in Tainan prefecture. On the other hand, I found no significant temporal bunching, in part because of the small total number of events for any single date. Recorded causes were more useful than date of occurrence in understanding who had been involved in these large-scale incidents. Police authorities provided causal arguments for none of the incidents of large-scale plunder, but of the remaining sixteen incidents of large-scale disorder, five involved conflicts over goods provisioning. In addition, information on thirteen of the large-scale incidents is sufficient to trace the “development” of an event. (In other words, the original recorder envisioned a violent event developing over time.) Though no “pattern” of protest or rioting emerges, it is significant that in ten of these incidents, specific conflicts, protests, or demands concentrated the crowd together and focused their attention on a particular (group of) victim(s). Banners articulating demands (or “requests”) were associated with two of these incidents.

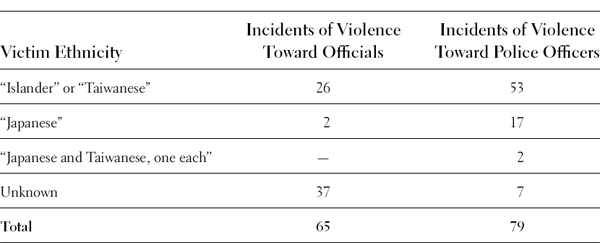

Victim Ethnicity Analysis

At least one-third (and probably far more) of the officials and two-thirds of the police officers cited as victims in these incidents of violence were labeled “Islander” or “Taiwanese” by the compiler of the report (see table 16.5). Although we will want to consider the complex meaning of the term “Taiwanese” in this late colonial context, the phenomenon it attempts to distinguish in the report is especially interesting, and suggests several types of questions: Is this unlawful behavior grass-roots condemnation of the Taiwanese collaboration with the colonial state? Would an organizational analysis of local police forces and local government offices prove, on the contrary, that these acts only represent dislike for colonial rule per se at an important transition period in the political history of the island? In other words, is it more likely that lower levels of the police and governmental bureaucracies were manned by “Islander” or “Taiwanese,” and therefore any postsurrender violent encounters that occurred would necessarily involve a greater percentage of “Islanders”/“Taiwanese”? Do the labels (and the actions that they attempt to record) challenge the goals and the stated claims of the kōminka movement in a fundamental way? These and other questions are addressed below.

Analysis of Victims’ Official Positions

Nearly all of the victims in attacks on police officers were patrolmen in direct contact with the local populace, though in some of the large-scale group protests that took place at the local police station, the police officer in charge was occasionally the target of attack. In contrast, violence toward public officials targeted a broader spectrum of local authorities, so a statistical analysis of this data presents additional information about these encounters (see table 16.6).

TABLE 16.5 Victim Ethnicity Analysis

Source: [Taiwan Kempeitai Shireibu], “Funjō boppatsu o yosō shieru chi-iki ni okeru jōhō,” [October 1945].

Three types of government services involve the majority of official victims: a) the staff of local government offices; b) officials involved in labor mobilization work (whether for air defense, general mobilization, or specific labor provisioning); and c) officials affiliated with agricultural affairs or the local agricultural association. In local areas these three entities (all interrelated) initiated and managed many of the demands made by the colonial government on the rural populace. Therefore, their presence on the roster of victims is not surprising. However, it does raise (for me) some more specific questions about late wartime governance and postsurrender assessment of colonial control: Do these acts of violence prove that late wartime mobilization of goods and labor at the local level was unreasonably harsh? (And can this proof of harsh rule be projected back earlier than 1945 or 1944?) In the execution of local governance, did town and village officials play a larger role in the active requisitioning of labor and goods than local patrolmen? Were these demands on rural resources the most important act of colonial government and therefore far more likely to cause enmity than other aspects of colonialism?

Stated Explanations for Incidents of Violence

Some tentative answers to the above questions can be found in the next set of figures (table 16.7). This list of motives for attacks upon officials and patrolmen corroborates some of my conclusions—namely, the wartime provisioning of labor and goods, as well as inequities in the requisition and assessment of these provisions and services, was a matter of contention between local communities and colonial authorities, and resulted in violent retribution in the fall of 1945. More than half of the military police report’s explanations for violent behavior directed toward public officials are related to this type of disagreement. Immediate conflicts, personal enmity, or revenge for prior arrests comprise a much smaller percentage of the explanations cited by military police intelligence.

TABLE 16.6 Victims’ Official Position Analysis

| Victim’s Official Position/Role | Number of Incidents Against |

| Government office staff | 20 |

| General affairs | 1 |

| Police station | 1 |

| Mobilization | 8 |

| Provisioning of labor | 2 |

| Air defense | 4 |

| Provisioning of goods | 1 |

| Rationing of goods | 1 |

| Agricultural affairs | 10 |

| Industrial affairs | 6 |

| Animal husbandry affairs | 1 |

| Education related | 2 |

| Railway | 2 |

| Unknown or uncertain | 6 |

| Total | 65 |

Source: [Taiwan Kempeitai Shireibu], “Funjō boppatsu o yosō shieru chi-iki ni okeru jōhō,” [October 1945].

Violence against police officers is not so easily explained. “Immediate conflicts” [my term; see note to table 16.7] comprise a larger number of the stated explanations here, and revenge for prior arrests or confiscation of gambling monies is as prominent a motive in this listing as the discontent over the requisitioning of goods. Although the large number of unknown or unstated causes precludes a stronger argument at this point, the list of stated causes suggests that postsurrender violence against the police was motivated differently from assaults on public officials.

Finally, let me say a word about police responses, based on the information found in the tabular data set, which is limited primarily to thefts (see table 16.8).14 First, it is important to remember that more than half of the thefts were still under investigation when the report was compiled. This suggests that either the authorities (police, military police, and local base security forces) were reluctant to pursue any vigorous investigation of these thefts of military property or their ability to investigate had been severely hampered—for any number of reasons. Nevertheless, the data in this table does indicate that sentries were still protecting military supplies at some facilities and that different types of policing forces were working together in order to minimize the loss of goods to “mass plunder.”

TABLE 16.7 Stated Causes for Incidents of Violence

| Stated Source of Discontent Leading to Violence | Resulting Number of Incidents |

| Against officials | |

| Conflicts over the provisioning of labor | 7 |

| Conflicts over labor mobilization | 4 |

| Demanding labor wages | 1 |

| Conflicts over air defense duties | 1 |

| Quota inequities (goods, labor, etc.) | 6 |

| Conflicts over provisioning of grains and goods | 8 |

| Demanding return of provisions (rice, eggs, etc.) | 5 |

| Demanding rice | 1 |

| Taxes and fees | 3 |

| Rationing inequities | 2 |

| Fertilizer distribution | 1 |

| Iron recycling | 1 |

| Previous arrests (or reporting leading to arrest) | 4 |

| Personal emnity | 4 |

| Improper official attitude | 2 |

| Official wrongdoing | 2 |

| Unknown or not specific | 13 |

| Total number of incidents | 65 |

| Against police officers | |

| Immediate conflict(*) | 16 |

| Previous arrest (or reporting leading to arrest) | 6 |

| Previous confiscation of goods or money | 3 |

| [Excessive] control of provisioning (grain, etc.) | 8 |

| Improper officer behavior | 2 |

| Fertilizer problem | 1 |

| Wages inappropriate for labor given | 1 |

| General discontent with officer’s regular duties | 4 |

| Unknown or not specific | 38 |

| Total number of incidents | 79 |

*Note: “Immediate conflicts” include: collecting information (2); arresting illegal slaughter (2); arresting illegal fishing (2); arresting illegal business transactions (2); arresting theft (1); arresting illegal gambling (1); arresting illegal tree cutting (1); interrupt fighting (1); labor pressing (1); over foodstuff (1); other (2).

Source: [Taiwan Kempeitai Shireibu], “Funjō boppatsu o yosō shieru chi-iki ni okeru jōhō” [October 1945].

OFFICIAL INTERPRETATIONS

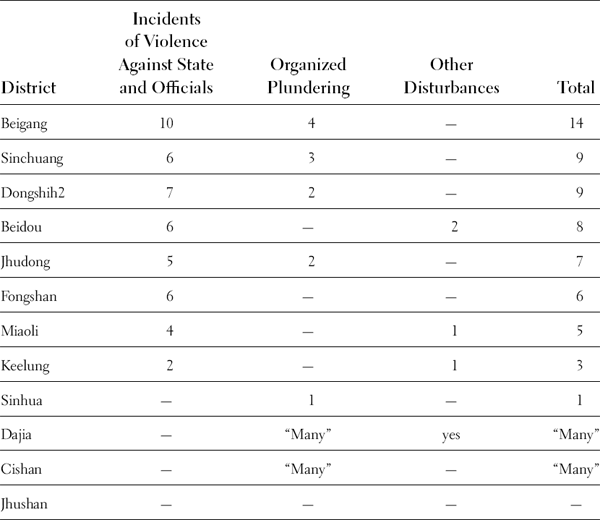

A report on “critical areas” where trouble was most likely to occur, compiled in November 1945 by the police bureau, singled out twelve districts and provided the relevant statistics for assaults, organized plundering, and other disturbances in each (see table 16.9).

A comparison of these results with the three data sources cited in the first section of this essay reveals some interesting discrepancies. Table 16.10 lists, based on total disturbances alone, the top ten areas where trouble was most likely to occur. It’s surprising that there is so little overlap between this set of three rankings and the “critical areas” in the November report (table 16.9).

Furthermore, it is important to note that in the descriptive analysis of “critical areas” in the November report the investigator did not cite quantitative data to support his list of twelve hotspots. Instead, he presented a historical argument: chronicles of early-20th-century resistance to Japanese rule had provided him with answers to the present dilemma. In the November report, the descriptions of each region and its “characteristic disorder” follow the same general narrative structure: Early colonial-era banditry (which included attacks on government offices and seizures of army materials) was suppressed by the Japanese military and police, without completely destroying anti-Japanese sentiment. For various reasons, cultural development in the region did not keep pace with other areas of the island, and lawless elements continued to exist. Consequently, in 1945, when the political situation began to change, local villagers believed the anti-Japanese propaganda of former bandits, who incited their followers to resist the colonial government. The author of the report literally took the history of region-specific social unrest in the early years of the colonial period as a mirror for predicting which areas would experience anti-Japanese disturbances in the fall of 1945.

TABLE 16.8 Police or Military Responses to Plunder Incidents

| Response | Plunder Incidents |

| Sentry discovered perpetrators, challenged them; they fled | 2 |

| Sentry fired weapon, and perpetrators fled | 1 |

| Sentry fired weapon, and some perpetrators were arrested | 1 |

| Criminals discovered/confirmed (and arrested) and materials recovered | 5 |

| Some criminals arrested and some materials recovered; rest being investigated | 5 |

| [Criminals] questioned, reprimanded, (forced to write an apology) released; goods returned | 3 |

| Criminals reported (and arrested) and matter under investigation | 1 |

| Criminals reported (and/or arrested) by military police; under investigation by the police | 2 |

| All goods recovered | 1 |

| Most goods recovered | 1 |

| Military detachment ordered to be more vigilant | 1 |

| Being investigated | 58 |

| Being investigated by military police with assistance from police | 1 |

| Being investigated with assistance from military police | 3 |

| Being investigated with assistance from military detachment | 6 |

| Response unknown | 3 |

| Total number of incidents | 96 |

Source: [Taiwan Kempeitai Shireibu], “Funjō boppatsu o yosō shieru chi-iki ni okeru jōhō” [October 1945].

TABLE 16.9 Police Bureau Summary of “Critical Areas” (November 1945)

There were also other interpretations in 1945. Three interim police reports15 and contemporary elite observers16 explained these popular acts of violence and plunder differently. Most describe (or assume) a foundational Taiwanese hatred for Japanese rule, though official accounts are ambivalent about the truth or power of these islander emotions. In the August and September police bureau reports, “Han Chinese nationalism” served as an equivalent term to classify one type of islander motive. However, careful attention to context and underlying assumptions reveals an important shade of difference among these various explanations. Police spokesmen inferred that news from China (or from Nationalist Chinese representatives in Taiwan in early September) drove a wedge between the Taiwanese and the Japanese; the changing situation and elite islander activism facilitated this distancing action. In contrast, elite Taiwanese observers, in particular those from the more conservative Nationalist camp, tended to describe this action as more of an awakening, in response to new circumstances and new potentialities. However, all contemporary observers agreed that popular characteristics were essential to the understanding of postsurrender developments. Police analysts depicted a Taiwanese propensity to look out for themselves, while elite Taiwanese observers across the political spectrum cited cultural and social backwardness of their lower-class brethren to explain acts of popular violence and plunder. Finally, whenever nationalism and cultural (or class) traits were necessary but insufficient explanations for disorder, official reporters tended to rely on the explanatory power of a rapidly changing situation: With each incidence of assault or theft, a spiraling circle of popular doubt in police abilities and the consequent decline in police effectiveness ensured the ultimate inability of a formerly powerful police force to control popular violence and plunder.

TABLE 16.10 Likely Troublespots Identified by Data Sets

* Areas included in November 1945 predictions (table 16.9).

MY ALTERNATIVE INTERPRETATION: CONCLUSIONS IN BRIEF

In the following two sections, I wish to present an alternative set of explanations for the tens and hundreds of conflicts from late August to mid-October 1945 that are recorded in postsurrender police reports. In brief, my argument consists of the following points:

1. Beginning in 1944, the colonial authorities made increasing demands upon local goods, possessions, and labor to meet the needs of the Japanese imperial military as it began to lose the Pacific War. By late 1945, these demands had taken a serious toll on the resources and personal well-being of the average Taiwanese.

2. A rapidly changing situation immediately following the announcement of Japan’s surrender in August provided a fertile context for innovative actions in citizen-police-official encounters. Stable parameters in these relationships were very difficult to gauge—by all parties.

3. Despite variations in practices and differences of effectiveness, police officers and local government officials continued their attempts to maintain social order and (where possible) to carry out many of their official duties. The data presented in the October 1945 military police report documents those official actions.

4. I do not consider elite Taiwanese activism to be the dominant storyline of this postsurrender drama. The record of elite activities tells us that their political maneuvering and competition during the months of August, September, and October resembled the activism of the pre-1937 period.

5. Finally, subaltern voices (and behavior) suggest that the postsurrender civilian actions documented in the police bureau’s “crime report” were a direct response to the wartime demands of the colonial state. From this perspective, these demands for various kinds of restitution and reimbursement were not crimes; and most were not motivated by the nationalism promoted by elite activists.

PROBING CONTEXTUAL KNOWLEDGE

Although I am unable to provide a comprehensive summary of late wartime demands for Taiwanese goods and labor, and the means by which those demands were met, perhaps I can suggest an outline of that rather complex and (to most of us) unclear history.

Increased Demands

All official sources indicate that local police and officials mobilized more provisions and labor in the last two years of the war than they had previously. To organize this increased exploitation, the colonial authorities made several changes in their hierarchy. In December 1943 the government-general established citizens mobilization departments and sections in prefectural, administrative-area, and district levels of government. In all towns and settlements, the authorities created a new specialized position to manage these mobilization affairs.17

After April 1944 there was a much greater need for local labor resources to construct additional military facilities (e.g., airfields, military roads). New government-general directives (first in July 1944 and then again in February 1945) mandated greater mobilization of local labor and established new organizations at all levels of government to control and manage these new resources efficiently.18 Most of this mobilizing was organized by local police and the officials of town government offices.19

In most (but not all) areas of the colony, the Japanese surrender in August 1945 brought an end to much of this wartime construction work. Mobilized work units were disbanded and returned home. Although colonial officials recognized the need for immediate reconstruction work, they were hesitant to organize this activity.20 The tabular data in the October military police report does suggest, however, that labor mobilization did continue in a few outlying towns and settlements.

The memoirs of one colonial official, Morita Shunsuke, remind us that one of the more important matters facing the colonial state in August 1945 was reimbursing these mobilized laborers for unpaid wartime wages.21 Morita sought to resolve the issue of unpaid wages before the Chinese authorities arrived. However, his attempt to obtain workers’ confirmation of the daily wage for this wartime work backfired when his selected workers’ representatives refused to accept the figure of 80 cash per day, which was the amount specified in the original state budget. Morita tells us why: Although (he contends, but I doubt, that) local governments had paid for the daily meals of laborers during the war, the black market rate for labor substitutes was as high as 2 yen per day. Thus, even Morita knew that 80 cash per day was an improper reimbursement in the minds of those who had loaned their labor to the state.

Greater Control

Most research on the wartime years has focused on the kōminka movement or the training of Taiwanese youth (both men and women) for service in the military.22 We know very little about the actual work of kōmin hōkōkai activities in local areas, in particular during the last two years of the war. Without more detailed research on this activity, it’s impossible for me to elaborate on the impact of these institutions and their activities on civilians in the postsurrender drama that I’m narrating.

Likewise, we also need more detailed studies of the day-to-day disciplining of local police forces as they attempted to mobilize increasingly more goods and labor to meet the needs of the Japanese military in 1945. The economic police force was a product of the war, initiated in 1938 and then institutionalized in 1940 when economic police divisions and departments were established in all prefectures and administrative areas. One indication of their duties would be the statistics on “economic crimes” committed in 1944.23 This source also gives us an indication of the major areas of conflict between populace and police. The highest number of crimes in this listing is for violations of the price-control regulations, but the next three or four major types of crimes on this list are all directly related to the postsurrender activities I’ve been discussing: violations of the regulations on pork rationing and hide rationing (related to illegal slaughter of livestock); and violations of regulations controlling the storage of unhulled rice and the rationing of rice and other grains (related to conflicts over provisioning, quota inequities, and grain rationing).

Japanese Officials and Elite Taiwanese as Participants

According to the August 1945 police reports, policing strategies were revised in that month on order to shift their primary focus to the maintenance of law and order; chaos prevention and maintaining basic living conditions were given the highest priorities. The central police bureau strengthened the work of special policing corps even as it encouraged the efforts of local police stations and ordered more frequent patrols. Local police chiefs were required to collect more intelligence on potential ideological and economic problems and report such information more rapidly to police headquarters. Police officers were instructed to avoid actions that might induce conflicts between Taiwanese and Japanese. It is likely that these changes in policy and practice had some impact on subsequent encounters between police officers and local islanders.

The story that I and others have previously told of these interactions between colonial officials and civilians has focused primarily upon the activities of a small group of well-known cultural and political elites, though several businessmen and a few professionals have played significant roles in some of our tales.24 Depending on the particular subject of research, historians have highlighted the machinations of pro-independence forces, the meetings of welcoming committees and their chairman, or the public rallies in late September and October that brought elite activists directly in contact with a broader segment of the (primarily) urban populace. Students and youth play a strong supporting role in these historical dramas. In some accounts they take responsibility for social control, garbage collection, and cultural censorship as early as late September. Yet youth deference to welcoming committee chairmen or the newly designated leaders of the “Three Peoples Principles Youth Corps” is repeated in many a memoir and biography.

More recent accounts help us understand the political maneuvering and competitive rivalries of all these groups and individuals, as well as the high stakes that such political battles involved. However, as I am attempting to argue in this essay, our histories have not explained the data on violent assaults and the plundering of military goods.

INTERPRETING SUBALTERN STATEMENTS

More than half the incidents of violence against local officials mentioned in this data involve some type of conflict over wartime provisioning, rationing, or the taxing of goods and services (see table 16.7). The statistics on violence committed against police officers are more difficult to interpret. Stated causes are not recorded for nearly half of these “crimes.” Of the remainder (41 incidents), only 13 incidents are specifically related to conflicts over provisioning, while 16 of the incidents involve more immediate conflicts between civilians and policemen. However, I wish to suggest that these numbers are also significant. The relatively higher incidence of immediate conflicts between police and civilians demonstrates that colonial police continued to perform their official duties, a strategy that may have placed them right in harm’s way.

Multiple Cases in One Area

New insight may also be found by exploring the multiple instances of crime in a single town or settlement. Only nine such multiple-incident sites can be detected in the tabular data. (Surprisingly, the map data is much less precise in this regard.) Three incidents of theft in Yuehmei village, Cishan district, suggest that the military was dispersing its stored provisions away from military bases in the latter months of the war, and this may have confused the issue of ownership in villagers’ minds. In addition, thefts of building materials near Hu-hsi-chuang in Penghu involved coastal encampments already abandoned by the Japanese navy in mid-September. And the so-called thefts at Man-chou settlement in Hengchun district were in fact only attempts; vigilant military guards prevented any loss of property, but we might also note that villagers attempted more than once to pilfer military supplies.

Multiple cases of violent assaults are not especially revealing. On September 24, in Hua-X settlement, Changhua district, the same thirty villagers apparently beat up more than ten officials in two separate incidents. Here the stated cause for the violence was declared to be civilian discontent with the high-handed attitude and behavior of local officials. The record of the late September and early October assaults in Dongshih settlement, Sinhua district, is decidedly more helpful because it shows an escalation of violence over the period of a week, as well as a strong degree of discontent. Approximately thirty Taiwanese assaulted an on-duty Taiwanese policeman on September 30. The same day, several Taiwanese injured a Taiwanese policeman who was attempting to check the household registry data in the settlement. Whether the same policeman was involved in both conflicts is impossible to determine, but it’s important to note that both assaults occurred away from government offices.

In contrast, on October 4 approximately two hundred villagers surrounded the police station in Dongshih settlement and demanded that the police chief return the fines and money that he had confiscated when he arrested suspected gamblers. This incident either was unresolved on that day or stimulated other recollections. The following day, several tens of villagers surrounded the station again in an attempt to force the police chief to apologize for his excessive zeal in the control of commercial transactions in the past. That the military police was called in to deal with the latter incident suggests to me that local authorities had to admit their weaknesses in the face of repeated villager demands.

Subaltern Demands or Threats

Finally, I turn to subaltern demands themselves. Like the rumors embedded in newspaper reports, the occasional demands, threats, or challenges that have been recorded in Japanese police reports can assist us in comprehending the complexities of subaltern motives. In this instance, the statements are few and the messages cannot be taken as verbatim or complete quotes. Nevertheless, I employ them to reiterate claims made by subaltern actions.

A single statement in a police report articulated a Nationalist claim, and would seem to confirm all the myths about postsurrender civilian-official conflict we have read in other accounts of the period. On September 9, when a solitary Japanese patrolman tried to curtail the work of five Taiwanese who were cutting trees from a windbreak (in Anting settlement, Sinhua district), the accused responded: “Taiwan is not Japan’s land. Why are you stopping us?” This is the only statement in the report that articulates this fundamental Taiwan vs. Japan difference.

Three of the eleven quotes demonstrate the utility of shouting a threat in a conflict situation. For example, pressing Donggang residents to join an announced work corps must have been dangerous business for the patrolman that five men threatened to destroy in early October. However, the swift dispersal of the five islanders, without any violent action taking place, attests the power of police authority even at this late date. On the other hand, the threat “I will kill this pitiful policeman who is all alone” (October 13, Chi-lung) reminds us of the insecurity of patrolmen and the increasing likelihood that they would abandon their out-of-office duties.

The rest of these recorded statements confirm the story that I have been trying to tell in this essay. Representing assaults or public protests that occurred between September 16 and October 11, these seven statements register a) vehement protests against the scale and inequity of wartime provisioning assessments; b) demands for the reimbursement of agricultural goods that were requisitioned by the imperial army; c) criticism of repeated attempts at tax collection in the postsurrender period; and d) denials of the legitimacy of police attempts to define “crimes” (e.g., gambling and illegal slaughter).

In short, the subaltern message that I have read in police reports and police crime statistics does not confirm the Nationalist tale previously told in our histories, but rather articulates a far more compelling story of late wartime exploitation and injustice, one that requires our further attention.

NOTES

1. I thank the many friends and colleagues who provided me with valuable feedback on earlier versions of this analysis. In December 1996, I first presented some of these findings to students in Wu Micha’s graduate symposium at National Taiwan University. Later the next year, I discussed revised analyses of this data in two settings: at one of the regular symposia of the Institute of Taiwan History at Academia Sinica, and for a group of graduate students at Chi Nan University. Several scholars at each of these gatherings suggested additional sources to me. In the summer of 2001, I also received much substantive input from scholars gathered for the “Symposium for Exchange Between Japanese and Taiwanese Historians of Taiwan,” at Ilan, Taiwan. In addition, I’m especially indebted to Wu Micha (for providing copies of Gaimushoo reports and police reports that were “companion volumes” to the reports, maps, and tabular data that I found in the U.S. National Archives) and Kondo Masami (for sharing reports from the thought-control police). Marc Schneiberg, a sociologist at Reed College, also gave my statistical analysis a careful specialist’s critique. For all of this assistance and feedback, I am truly grateful.

2. Yeh Jung-chung 1985: 283.

3. Taiwan Sōtokufu, Keimukyoku, November 1945.

4. For example, Chen Tsui-lien 1994, 1995.

5. See Taiwan Sōtokufu, Keimukyoku, November 1945; and Taiwan Kempeitai Shireibu, [Tabular data], October 1945.

6. Taiwan Kempeitai Shireibu, October 1945.

7. Taiwan Sōtokufu, Keimukyoku, November 1945.

8. Taiwan Sōtokufu, Keimukyoku, November 1945.

9. Taiwan Kempeitai Shireibu, October 1945.

10. The figure of twenty-seven violent incidents for Taipei City in table 16.2 includes two incidents for Taipei City south and twenty-five incidents for Taipei City north.

11. Marc Schneiberg has even suggested that this evidence provides a “powerful rebuttal of the alternative hypotheses for all of [my] data: that these patterns reflect business as usual.” For example, the tabular data associates the theft of building materials in Kaohsiung City on September 15 with the “dissolution of the commissariat for the headquarters of the Kaohsiung strategic area.”

12. Source: Taiwan Kempeitai Shireibu, October 1945.

13. Based on the presentation of information in the data as a whole, I do think this reference to “villagers” represents a rather small number of people involved in each case of collective theft or plunder.

14. The information on responses to assaults in the tabular data set was brief and unitary, giving me very little insight into this type of conflict.

15. Taiwan Sōtokufu, Keimukyoku, August and September 1945.

16. Yeh 1967; Chen Yi-sung 1994; Wu 1981.

17. See Taiwan tōchi gaiyō and Tsai 1994, 1995. For example, one of Tsai Hui-yü’s informants told her that clerks in charge of mobilizing local labor resources were established within the local public office in towns and settlements in the Kaohsiung in late wartime.

18. Taiwan tōchi gaiyō.

19. Tsai 1994, 1995.

20. Taiwan tōchi gaiyō.

21. Morita 1979.

22. For example, Kondō 1996; Li 1997.

23. Taiwan tōchi gaiyō, pp. 111–115.

24. For example, Chen Tsui-lien 1995; He 1998; Kondō 1996.

REFERENCES

Chen Tsui-lien  . 1994. “228 shih-chien yen-chiu

. 1994. “228 shih-chien yen-chiu  .” Ph.D. diss., Graduate Institute of Political Science, National Taiwan University.

.” Ph.D. diss., Graduate Institute of Political Science, National Taiwan University.

———. 1995. P’ai-hsi tou-cheng ch’uan-mou cheng-chih  . Taipei: Shih Pao.

. Taipei: Shih Pao.

Chen Yisong  . 1994. Ch’en Yi-sung hui-yi-lu

. 1994. Ch’en Yi-sung hui-yi-lu  . Wu Chun-ying and Lin Chung-sheng, compilers. Taipei: Ch’ien Wei.

. Wu Chun-ying and Lin Chung-sheng, compilers. Taipei: Ch’ien Wei.

Fix, Douglas. “Taiwanese Nationalism and Its Late Colonial Context.” Ph.D. diss., University of California, Berkeley

Gaimushō, Kanrikyoku, Sōmubu, Nampōka  . 1946. “Taiwan no genkyō

. 1946. “Taiwan no genkyō  .” February 10.

.” February 10.

———. 1946. “Taiwan kankei  .” March 10.

.” March 10.

He Yi-lin  . 1998. “Taiwanjin no seiji shakai to 228 jiken

. 1998. “Taiwanjin no seiji shakai to 228 jiken

.” Ph.D. diss., University of Tokyo.

.” Ph.D. diss., University of Tokyo.

Ikeda Toshio  . 1982. “Haisen nikki

. 1982. “Haisen nikki  .” Taiwan Kin Gendaishi Kenkyuu 4:55–108.

.” Taiwan Kin Gendaishi Kenkyuu 4:55–108.

Kondō Masami  . 1996. Sōryokusen to Taiwan: Nihon shokuminchi hōkai no kenkyū

. 1996. Sōryokusen to Taiwan: Nihon shokuminchi hōkai no kenkyū  . Tokyo: Tōsui Shobo.

. Tokyo: Tōsui Shobo.

Li Kuo-sheng  . 1997. “Chan-cheng yü T’ai-wan-jen: Chih-min cheng-fu tui T’ai-wan te chun-shih jen-li tung-yuan

. 1997. “Chan-cheng yü T’ai-wan-jen: Chih-min cheng-fu tui T’ai-wan te chun-shih jen-li tung-yuan  (1937–1945).” M.A. thesis, Graduate Institute of History, National Taiwan University.

(1937–1945).” M.A. thesis, Graduate Institute of History, National Taiwan University.

Morita Shunsuke  . 1979. Nai Tai gojūnen mokuji: Kaisō to zuihitsu

. 1979. Nai Tai gojūnen mokuji: Kaisō to zuihitsu

. [Tokyo].

. [Tokyo].

Mukōyama Hiroo  . 1987. Nihon tōchika ni okeru Taiwan minzoku undōshi

. 1987. Nihon tōchika ni okeru Taiwan minzoku undōshi

. Tokyo: Chuuō Keizai Kenkyuujo.

. Tokyo: Chuuō Keizai Kenkyuujo.

Shiomi Shunji  . 1979. Hiroku: Shūsen chokugo no Taiwan: Watakushi no shūsen nikki

. 1979. Hiroku: Shūsen chokugo no Taiwan: Watakushi no shūsen nikki  . Kochi: Kochi Shinbunsha.

. Kochi: Kochi Shinbunsha.

Strategic Services Unit, Canary Mission. 1945. “Cables (outgoing).” September–November. [Taiwan Kempeitai Shireibu  .] 1945. “Funjō boppatsu o ŷosō shieru chiiki ni okeru jōhō

.] 1945. “Funjō boppatsu o ŷosō shieru chiiki ni okeru jōhō  .” [Tabular data.] [October].

.” [Tabular data.] [October].

[———.] 1945. “Kiō no hassei jiken yori mitaru funjō boppatsu kanōsei chiiki gaikenzu

.” Map. [October 1945].

.” Map. [October 1945].

Taiwan Sōtokufu  1945. (Shōwa nijūnen) Taiwan tōchi gaiyō

1945. (Shōwa nijūnen) Taiwan tōchi gaiyō

. Taihoku, [1945].

. Taihoku, [1945].

Taiwan Sōtokufu, Keimukyoku. 1945. “Taishō kampatsu ato ni okeru tōnai chian jyōkyō nara[bi ni] keisatsu sochi (dai-ichi hō)

.” August 1945.

.” August 1945.

———. 1945. “Taishō kampatsu ato ni okeru tōnai chian jyōkyō nara[bi ni] keisatsu sochi (dai-ni hō)  .” August 1945.

.” August 1945.

———. 1945. “Shūsen ato ni okeru tōnai chian jyōkyō nara[bi ni] keisatsu sochi (dai-san hō)  .” September 1945.

.” September 1945.

———. 1945. “Sōjō boppatsu no kanōsei aru chi-iki ni kan suru jōhō

.” [“Critical areas of activity”.] November 1945.

.” [“Critical areas of activity”.] November 1945.

Ts’ai Hui-yu  . “Pao-cheng, pao-chia shu-chi, chieh chuang yi-ch’ang

. “Pao-cheng, pao-chia shu-chi, chieh chuang yi-ch’ang

.” Shih Lien 23 (1993): 23–40; Taiwan Fengwu 44.2 (1994): 69–111; Taiwan Fengwu 45.4 (1995): 83–106.

.” Shih Lien 23 (1993): 23–40; Taiwan Fengwu 44.2 (1994): 69–111; Taiwan Fengwu 45.4 (1995): 83–106.

———. 1995. “Pao-cheng, pao-chia shu-chi, chieh chuang yi-ch’ang—K’ou-shu li-shih

.” Taiwanshih Yenchiu 2.2:187–214.

.” Taiwanshih Yenchiu 2.2:187–214.

Wu Hsin-jung  . 1981. Wu Hsin-jung rih-chi (chan-hou)

. 1981. Wu Hsin-jung rih-chi (chan-hou)  . Chang Liang-tse, editor. Taipei: Yuan Ching.

. Chang Liang-tse, editor. Taipei: Yuan Ching.

———. 1989. Wu Hsin-jung hui-yi-lu  . Lin Heng-che, et al., editors. Taipei:Ch’ien Wei.

. Lin Heng-che, et al., editors. Taipei:Ch’ien Wei.

Yeh Jung-chung  . 1985. “T’ai-wan-sheng kuang-fu ch’ien-hou te hui-yi

. 1985. “T’ai-wan-sheng kuang-fu ch’ien-hou te hui-yi

.” Taiwan jen-wu ch’ün-hsiang. Taipei: Po-mi-erh. Reprinted from Hsiao-wu ta-ch’e chi (Taipei: Chung-yang Shu-chu, 1967).

.” Taiwan jen-wu ch’ün-hsiang. Taipei: Po-mi-erh. Reprinted from Hsiao-wu ta-ch’e chi (Taipei: Chung-yang Shu-chu, 1967).