CHAPTER 10

Sea Trials and Commissioning Finishing It All Up

Copyright © 2006 by International Marine. Click here for terms of use.

At some point in the restoration process, the jobs left to do cease to be "rebuilding projects" and start to become "ownership projects." I spent two years and five months of part-time work restoring my boat. It wasn't "finished" at that point, but it was ready for its sea trials (perhaps we should call them "lake trials") and commissioning.

Sea trials of your newly restored boat will be more important than with most boats. No matter how much planning and thinking you do, you'll find some glaring deficiencies in your boat the first time you sail it—I promise. Launch your boat, and bring a ruler and a clipboard. Take notes of all the things that need to be done, relocated, changed, and so on. Hopefully, you won't need to change or add that much.

I first launched the boat in late August. I left her in the water for most of the fall, taking several sails in varying conditions. Each time, I noticed something that would need changing—not immediately, but when I hauled the boat for the winter. For example:

The mainsail headboard chafed against the backstay, and the new main is a bit too long. The stock MacGregor masthead for the year my boat was built uses cheek blocks on the sides of the mast. If, however, I use a masthead with sheaves built in (like a stock masthead from Dwyer Mast Company), I'll gain maybe an inch or two of hoist. Plus, the masthead extends the headstay and backstay attachment points out a few inches from the mast, giving the sail's headboard a little extra room. Hopefully, the change in halyard lead will make them a little less likely to foul the steaming light, which has also been a problem.

Stowage below is inadequate, and I need to make an inventory list of things that will stay on the boat, along with locations for each item. Small eyelets for bungee cords need to be installed pretty much everywhere, as I've had a few sails where everything ended up on the floor.

Many other small things were deferred until later, like installing the VHF, final bolting of the head cabinet, screen bags and snaps, and so on. All these things are going on the "winter boatwork" list. You'll find that you have a list like this every winter. I find that some boatwork is enjoyable in the winter, as long as it isn't too ambitious.

Outfitting for Sailing

One of the shortcomings of restoring a boat will be felt acutely now, and that's the fact that you have to buy a ton of little doodads that would normally come with a better-kept vessel—fenders, dock-lines, life jackets, whistles for each, a horn, a fire extinguisher, some sailing gloves . . . the list can seem endless and can get pretty expensive. But these are the inescapable costs that you'll have to pay for just about any kind of watercraft, so just grit your teeth and get out the wallet. It only hurts for a few moments when you're handing over those bills anyway; you'll forget all about it once you get on the water.

At the very least, though, you should have aboard the complete list of equipment required by the Coast Guard. For the size boat we're discussing here, this means Coast Guard Class 1, 16 to 26 feet in length. The list includes (but may not be limited to):

Personal Flotation Devices (PFDs). One for each person onboard, plus one throwable. We have four aboard, properly sized for kids and adults.

Fire Extinguishers. Not specifically required, since my boat is under 26 feet and outboard-powered, but we have one anyway.

Ventilators. These are required on inboard boats, and on boats that keep their gas in lockers. I keep my tank on deck, in the outboard well.

Whistle/Bell. The Coast Guard requires Class 1 boats (of which your trailer sailer is an example) to carry a device capable of making an "efficient sound signal." We have a Freon horn in a dedicated cockpit holder. Plus, we have whistles tied to each of the life jackets. Whistles are not commonly considered "efficient sound signal devices" by the Coast Guard, but they are useful in man-overboard situations. If you sail in areas with fog, a ship's bell becomes an important signaling device, rather than a shippy nautical decoration.

Visual Distress Signals. Although sailboats under 26 feet are exempt from this, Coast Guard regulations require that you carry a bright orange flag with a black square and disc for daytime use. It's a good idea to have a distress flag aboard no matter what size boat you sail. Smoke signals can also be used, but they have to be currently dated. At night, the visual distress requirement can be satisfied with a flashlight capable of signaling SOS, but we carry flares as well. A new development in nighttime distress signaling is a small handheld laser. These look much like inexpensive laser pointers, but rather than a single dot of light (which is very difficult to aim) these new lasers produce a vertical band of laser light that can be pointed towards a target at a very great distance.

Surprisingly, this is all that is required by the Coast Guard, but the list is far from complete. Good anchors are extremely important. You should have at least one anchor, preferably two, with plenty of line. Don't scrimp on anchors . . . get good ones, properly sized for your boat. There have been whole books devoted to the subject of anchors and anchoring, and anchor manufacturers have published tables of recommended sizes for different sailboats. For example, Simpson Lawrence recommends an 11-lb Claw anchor for boats up to 23 feet, and Danforth says that their 5-lb Danforth Hi-Tensile anchors with 1,000 lbs of "holding power," are good for boats 24 to 31 feet in length. It's good to have several different types of anchors aboard, because different bottom conditions have a great impact on holding power. Again, do not buy cheap anchors . . . those little PVC-coated "mushroom anchors" do little more than sink your line to the bottom, and will not hold a sailboat in position in anything but a dead calm. With most anchors, a length of chain is required to help them set properly. Correctly-sized rodes (the line connecting the anchor to the boat) are a necessity, as well as strong cleats to make the rodes fast to the boat. An oversized "storm anchor" is often carried on many boats, but I'm of the opinion that a correctly-sized, high-quality anchor (such as a genuine Danforth, CQR, Delta, Bruce, or Claw) is better than an oversize, inexpensive copy.

Oars. Some kind of alternate propulsion, like an oar, is a real blessing to have if—or perhaps I should say when—your engine croaks in a flat calm. I'm still trying to come up with some way to row my boat: the oars need to be quite

|

A NOTE ON HORNS . . .

|

|

You should always know exactly where your horn is stowed and be able to retrieve it quickly. I learned this the hard way. Once, when I was a liveaboard, I was onboard my boat during a very large storm. I was anchored upriver, along with several other boats. When the windspeed increased to over 80 knots, most of the boats upwind of me began to drag anchor, including a large powerboat who was trying to use his engines to keep headed bow-to-wind. At one point during the night, the captain was getting tired, and began to drift straight for my still anchored boat. He was very close. I vividly remember tearing through the cockpit locker, tossing lines, winch handles, and other junk out of the way, frantically looking for my freon horn. I finally found it and blew a long blast . . . the power boat was within fifteen feet of me. The moral of the story is that you won't need your horn every day, but when you do need it, you'll likely need it immediately. In my case, it very nearly cost me my boat. So give it a dedicated spot to live and make sure it's ready when you need it.

|

Various used boat electronics, all purchased on eBay. Some were brand-new, some needed repairs, but most were pretty good buys. If you're all thumbs when it comes to electronics, though, you're better off buying new or doing without.

long to work. Sculling is a possibility, though I haven't yet mastered the fine points of this art form. (See Appendix 2 for a discussion on how to build your own oars.)

Tie-Downs. One of the other things that you'll need to do when commissioning is figure out ways to secure all this stuff that you're bringing aboard. I had a couple of early sails where everything ended up on the floor, since my boat will heel past 40 degrees relatively easily (at about 18 knots of wind). Lightweight items are rather easy to secure with small or medium-size bungee cords and stainless eyes. Larger items, such as the water tank and battery, required larger cords and eyes. Figuring out the best place to put things, and the best way to secure them, will definitely require some trial and error.

Electronic Equipment for Small Boats

As I neared the completion of my boat, I began to consider adding a few electronic extras. These things aren't essential—yachtsmen got along fine without them for years—but they were things I wanted to have, mostly just for fun. They added cost and complexity to my boat, to be sure. But

|

WHAT'S DSC?

|

|

It's short for "digital selective calling," and the hope is that it will revolutionize the way rescue operations are handled. DSC uses a digital signal to transmit specific information, such as:

|

|

The caller's unique ID number (similar to a telephone number) The caller's unique ID number (similar to a telephone number)

|

|

The ID number of the unit being called, for example all Coast Guard stations The ID number of the unit being called, for example all Coast Guard stations

|

|

The caller's location and the time of the call The caller's location and the time of the call

|

|

The requested working frequency The requested working frequency

|

|

The priority and type of the call (collision, crew overboard, fire, sinking, piracy, and so on) The priority and type of the call (collision, crew overboard, fire, sinking, piracy, and so on)

|

|

Ideally, DSC will eliminate much of the human factor in monitoring radio frequencies for distress calls. There are still plenty of bugs in the system. For example, the Coast Guard is being plagued with large numbers of relayed DSC distress signals, 99 percent of which are accidental transmissions. It remains to be seen if DSC will mature into a vastly improved communications system as promised.

|

a few trade-offs can keep the downside of electronic equipment to a minimum.

VHF Radio

I installed a VHF radio and a depth sounder. New radios can get quite expensive, so I figured I'd save some money by buying a used one on eBay. I did save money—my VHF cost only $56. But it didn't come with any power connections or antenna. So I bought an antenna on eBay for $45, but then I had to figure out where to install it. It was too big for the masthead, so I bought an antenna mount and put it on the stern quarter. It will fold down, and it's in the way only part of the time. But I should have bought a handheld. They can be purchased brand-new for $130 or so, require no installation, and their range on the lake is more than adequate. As it is, I've had quite a bit of grief installing the radio. It's an old unit that could fail at any time, and I didn't save that much. To add insult to injury, when I finally got everything powered up, no audio. Everything seems to be working, it appears to transmit, but you can't hear a thing. So here's a case where it's definitely better to buy new if you really want a VHF.

A VHF radio isn't a necessity, but it's nice to have for safety and convenience. Cell-phone coverage is kind of iffy in coastal waters (but this is improving all the time), and cell phones are useless for ship-to-ship communication. (You aren't likely to know the phone number for a tug that's rounding the river with a big tow, nor does he broadcast security information via cell phone.) VHF weather broadcast information is very handy to have aboard, especially with our smaller vessels, where being caught in a storm can make a bigger impression. You no longer need an FCC license to operate a VHF ship station, but you need to know the rules. A good website that outlines VHF operations is at www.boatsafe.com/nauticalknowhow/radio.htm#ch.

Depth Sounder

My depth sounder was another story. The cheapest brand-new unit I could find was $100 on sale, and they're more usually found at about $150. A depth sounder is nice to have, as it can really help with your navigation by following a contour. A grounding isn't nearly the inconvenience with a trailer sailer that it is with a keelboat, but it's good to avoid. I had one on my previous boat, and it was a great comfort to know how deep the water was where I was sailing.

There are two basic types of depth sounders. Older ones of the type most commonly used on sailboats have analog dial displays, while more recent ones have digital readouts. The other type is the old fish-finder-style, which uses a revolving neon bulb on a dial face. These are usually larger than the digital type, but they can give a little more information about the bottom density and obstructions, and they can locate schools of fish. They'd be an excellent choice to use in your dinghy to scout out anchorages.

I bought a used sounder on eBay, but I had a world of trouble with it, so I wouldn't recommend this route. I've learned the hard way that used electronics are often false economy. Newer sounders, and new electronics in general, are more compact, work better, have greater functionality, have more readable displays, and come complete with all the parts and factory support. When it comes to marine VHF radios, only a new unit will get you DSC, which is a very cool new feature (see sidebar).

There is, however, a good, low-tech alternative (or supplement) to an electronic depth sounder.

A Lead Line. While you're out buying stuff, pick up a big fishing sinker and some lightweight cord to make a lead line. Even if you have a depth sounder, there will be a time when you'll need to heave the line—the battery will die, or your sender will get dirty, or you'll just want to verify that there really is only 3 feet of water under you.

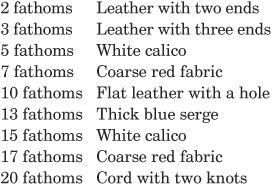

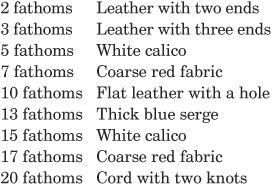

Ferenc Maté gives instructions for making a traditional lead line in his book, The Finely Fitted Yacht. A traditional lead line has a large, heavy weight, about ½ inch in diameter, and weighing about 5 or 6 pounds. The line is marked with different materials at varying depths, as follows:

Normally, I like traditional ways and gear aboard boats, as time-proven designs are often the best, but not this time. The traditional lead line was designed for use aboard sailing ships, and the boats we sail are closer in size to the ship's dinghy. Everything can be much smaller—the line, the weight, and the spaces between the marks. Boat chandleries sell little plastic tags with numbers on them. I'd skip these—they don't last, and they're impossible to read by feel.

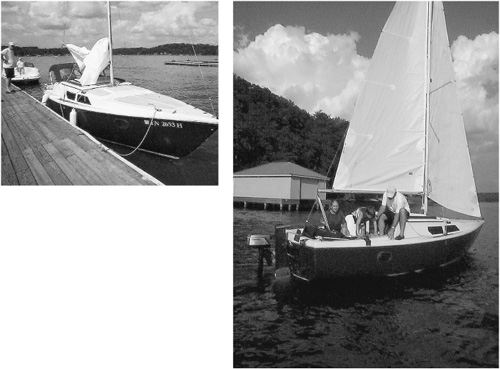

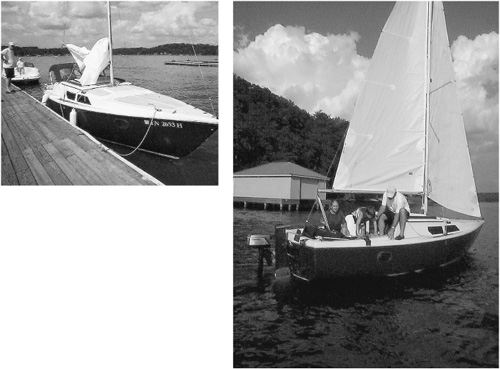

Launch day. The boat is rolled out of the drydock it's called home for the last two years and headed for the lake near our house. Don't forget to buy insurance before taking this step!

My lead line is made of 1/8-inch-diameter braided cord. I have knots in the cord every 3 feet. Measured from the bottom of the weight, one knot for 3 feet, two knots for 6 feet, three knots for 9 feet, and a piece of leather at 12 feet (two fathoms). You can even stamp a 12 on the piece of leather to help remind you of the system. From then on, the line follows the traditional system, with the addition of single knots at 4 fathoms and 6 fathoms. My line stops at 40 feet, though I'd use a longer line on a blue-water passage. If you really want to get traditional, bore a shallow hole in the bottom of the sinker. Put a little Crisco in the hole, and you can bring up a small sample of the bottom to help determine what type of anchor you should use—try that with an electric depth sounder! Yet another method, which may be a little easier, is to use nylon zip ties to mark the depth, though this may be a little harsh on your hands when you're heaving the line.

The Payoff

A few weeks after the initial launch of my boat, a few other MacGregor owners brought their boats to Chattanooga for an inaugural day sail. Six people I hardly knew drove half a day just to help me celebrate. The wind was blowing nicely, and as we heeled to the freshening breeze, I looked up at the sails. That's when I realized that, finally, I was sailing again with my own boat under me. It

(above) Four hours later, and we're in the water. The first time out will definitely be taxing as you try to figure out where everything goes. (right) The first day out, we had very little wind. My 7-year-old son prepares to abandon ship after loudly proclaiming, "This is boring," and, "I can walk faster than this!" Sailing with children requires quite a bit of advance preparation and ready diversions, but that's another book.

took time and money, but I really have something to show for it. Oh, sure, there's still plenty to do, but that's true with any boat. For now, I really enjoyed watching the curve that was pressed into the sailcloth by the breeze, the feeling of movement, and the quiet splashing of water running past the hull. The fact that this was a direct result of my work made the day that much sweeter.

If you choose to rebuild an old sailboat, and I hope you do, I wish you all the success in the world. May all your bolt holes line up, and may all your epoxy cure without a hitch. Make no mistake: it's a serious commitment of time and money. Don't give up—keep at it. When you get to the point of actually sailing, be sure to savor that moment. Everyone deserves that feeling once in his lifetime.

Fair winds,

Brian Gilbert