CHAPTER 1

Why Restore a Small Boat? Economics, Practical Considerations, and Having It Your Way

Copyright © 2006 by International Marine. Click here for terms of use.

Once upon a time—a long, long time ago—I owned and lived aboard a Catalina 27. For roughly four years, I lived aboard my boat. Then I decided it was time to go back to school. I sold the boat, moved inland, and used the money to get married and earn my master's degree.

I had always heard it said that the two greatest days in a sailor's life are the day he buys his boat and the day he sells it. Pardon me for saying so, but that's a boatload of manure. I was grateful to sell my boat, but it took all of two weeks before I started feeling like I had made a mistake. Almost immediately I started thinking about another boat to buy.

Eight years and one baby later, I still had no boat. The money for a sailboat always seemed to be urgently needed for one bill or another, so my wife and I had very little to work with. I decided to sit down and define the parameters for a boat that would fit my family's lifestyle.

Part of the problem was me: Having lived aboard a boat, I had definite ideas about what I wanted: a large, high-quality yacht. But my dream boat was totally unrealistic, at least at this stage of my life—newly married, fresh from grad school, unable to find work that capitalized on my degree, with a baby thrown into the mix. We didn't go too crazy buying stuff for our son, but we did want one of us to stay home with our son, and the lost income became significant. As our son Kyle got older, my wife was able to land a good job, I found a part-time editing contract (with flexible hours so I could homeschool Kyle), and we moved into a new house (with the accompanying mortgage and expenses). There was a little money left over after we paid the bills, but not much. I soon understood that there would never be enough to go out and buy that Island Packet 32.

That's when I finally settled on the idea of a trailerable sailboat—something that I could use to dash away for quick day sails, the occasional overnight or weekend cruise, and maybe a little longer trip once or twice a year. So I sat down and tried to turn my rather amorphous daydreams into concrete plans. Our sailboat would have to be:

1. Affordable. Although this can mean widely different things to different people, with us it meant really, really affordable—as in, not a lot of money at all. Like many young families, we had numerous priorities (our young son, for example) that ate up what little cash we had left over at the end of the month.

2. Small. A smaller boat would be a great deal cheaper and would suit the lake sailing that we'd be doing. Oh, sure, I'll cruise the Caribbean someday, but in the meantime, I could sail this boat. Then, when the tropical breezes start to blow my way, I can use the equity in the small boat to move up to something larger. I did want a boat that was large enough to sleep on in relative comfort, meaning some form of cabin (a Catalina 22, for example).

3. Trailerable. A boat on wheels can be vastly more flexible to use than one that's stuck in the water. Trailerability also reduces maintenance expenses and improves affordability, as I describe in more detail in the next section.

4. Quick. The boat had to be quick to fix, quick to rig, quick to launch, and quick to sail. It seems that time is a rare commodity these days, and we needed a boat that didn't take up all our spare minutes.

The only thing that seemed to fill all these requirements was an older, small sailboat (18—23 feet), with a trailer, in need of some repairs and maintenance. I eventually found one that came close, though it ended up needing a lot more repairs than I planned on. More about my particular choice later.

Reducing the Costs of Sailing

Our boat would have to be cheap—both to buy and to maintain. I figured I could come up with about $1,500 to buy the boat, which is not a lot of money. Realistically, the only boats in this range are trailerable.

A trailerable boat gives you options for storing it in the off season that larger boats don't have. You can keep it in your backyard and work on it over the winter if you like, or store it on the trailer in a rental yard or marina. Stick it in a slip during the summer months, and you'll be sailing at the drop of a hat. Some marinas will rent a parking space near their boat ramp where the boat can be kept fully rigged. As long as there aren't any overhead power lines, you can load up the car, drive to the marina, hook up the trailer, and slide it into the water. This can be a lot easier than trailering from house to the water every time you want to sail (although you still have that option), and it can be a lot cheaper than keeping the boat in a slip.

A trailerable boat kept at home is accessible for work without the haulout, yard fees, and trucking expenses that larger boats require. This reduces the cost of maintenance. Parking the boat in the backyard over the winter enables you to dash out and do a quick job whenever you have a free moment, instead of having to pack up the tools, drive to the yard or storage facility, discover you've forgotten something, and spend the rest of the day cursing your absentmindedness.

Cash Value

Generally speaking, sailboats are very poor investments. We've all heard the "hole-in-the-water-into-which-you-pour-money" bit. However, I've never heard this phrase from someone who actually owns and uses a boat. Oversimplifications like this are usually pronounced gleefully by landlubbers.

But there is a grain of truth there. Sailboats in top condition can bring a price that's vastly different from the price of a boat that's been neglected. What some people fail to realize is that the difference is often less than the restoration cost, especially if you do all the work yourself.

That said, a sailboat is not like a car, where the value drops every year until it effectively reaches zero and you haul the thing to the dump. As long as the hull is basically sound, nearly any fiberglass boat can be restored. The restored boat, in good condition, can be sold for a reasonable amount of money—its value is preserved, up to a point. A boat doesn't appreciate in value the way real estate does, but its worth doesn't evaporate like a car either. I like to think of a boat like a bank account that doesn't earn any interest—the money is always there and can be recovered to some degree when it's time to sell. But a boat is a whole lot more fun than a bank account.

Emotional Reasons

Buying a sailboat isn't like buying a toaster. You can't really weigh features against price, then pick the best value; there are too many variables involved. One of those variables involves your feelings. Don't ignore them. Sailing is mainly an aesthetic activity; it's not essential for our survival. So the aesthetics of the boat, and your feelings about sailing, need considering, too.

I like the idea of fixing up a boat. It preserves the resources that went into creating it, and in all cases those resources are considerable. Thousands of pounds of fiberglass and resin have been kept out of a landfill because of my efforts. Some boats (not mine) have teak in them, and with the replacement price of teak reaching $15 per board foot, you'd be crazy to throw it away. With my boat, I took an ugly, useless eyesore and made it into something functional and, to my mind at least, fairly good-looking. I get a tremendous amount of satisfaction from that. You can, too.

You've probably heard this old adage from the world of real estate: "What are the three most important things to consider when buying a house? Location, location, and location." Well, the equivalent adage with boats could be "Condition, condition, and condition." Neither phrase is an absolute truth, but it's valid to say that condition is one of the single most important determinants of a boat's value. And while this book is about buying a junker cheap and fixing her up, you'd be nuts not to consider paying a little more for a boat in markedly better condition. Sometimes a boat that is a little dated, but relatively clean and ready-to-use, can be purchased for perhaps $1,000 more than a similar boat in dismal condition. This is especially true with smaller, trailerable-sized boats. If you have the cash, spending it up front, making a few upgrades as time and cash allow, and sailing sooner will usually (but not always) make more sense. This may not be the case if you're really tight on disposable cash, or if you have definite ideas about sailing and how you want to set up your boat.

Which Boat?

On any given day, there are thousands of different boats in your size and price range for sale in the United States. How do you decide which one is the best choice?

First off, don't try to find the best choice. Concentrate instead on making a good choice. So many people get hung up on finding the "perfect" boat, but this boat doesn't exist. All boats are compromises, so develop a flexible attitude. Think about the type of sailing you want to do. Are you a racer at heart, or does the thought of a hot cup of coffee in the morning mist get your heart thumping? Maybe you'd like a little of both? Where will you be sailing? San Francisco Bay commonly has 35-knot winds, while the lakes where I sail are often dead calm. Each area has boat types that are better suited to it. Will you be sailing alone or with a crew? With your husband or wife? With kids? (These last two are especially important, because in my house at least, if they ain't happy, nobody's happy. So try to include them in the process.)

Physical Location of the Boat

An important factor to consider when buying a boat is its physical location. Depending on where you live and plan to sail, the cost of the boat you choose can go up—sometimes significantly. For example, let's say you live outside of the major sailing areas (as I do) and you find a great deal on a Cal 25. Trouble is, it's in California, you're not, and it doesn't come with a trailer. You could have the boat trucked to you at a cost of about $3,000. Add the cost of getting the boat on and off the truck, and suddenly your great deal isn't so great. If you have a vehicle capable of towing it, you might get lucky and find a boat with a trailer—but the trailer will likely need some work to make it roadworthy. If you don't have a vehicle capable of towing, one option might be to rent an empty U-Haul truck

|

SAILING TERMS

|

|

The term knots means "nautical miles per hour." So you don't want to say "The wind was blowing at 35 knots per hour" to describe the wind speed, or you'll be immediately recognized as a landlubber . . . or a geophysicist (they use the term knots per hour to describe acceleration, but not speed).

|

|

A nautical mile ("6,076.11549 feet approximately," according to Bowditch) is slightly longer than a statute mile—about 1.15 times longer. It equals 1/60th of a degree or 1 minute of latitude. The difference came about when people discovered that the Romans weren't quite right when they estimated the size of the Earth. Mariners adopted the corrected figure, while people ashore kept the old measurement, the statute mile (5,280 feet).

|

|

WHAT'S A BUC?

|

|

BUC International Corporation is a marine industry service corporation that has been around for 40 years. It began by publishing the BUC Used Boat Price Guides in 1961 with only 5,000 entries. Today, the "BUC books" are an industry standard, containing values for over 700,000 used boats. You can purchase BUC's printed price guides, or look up values online at www.bucvalu.com.

|

|

A word about the BUC values: BUC defines "average condition" this way: "Average condition means that the vessel is ready for sale, requiring no additional work and normally equipped for its size." So a boat that "needs some cleaning" is below average or poor, depending on the work required. Likewise, incomplete boats (boats without a mast) are not considered "normally equipped," so they command a lower price as well. Note that the BUC value does not include the trailer or motor.

|

|

NADA also publishes a boat price guide. Its website is www.nadaguides.com.

|

and use that to tow the boat. The bottom line: The closer to home your prospective purchase is, the better.

As you think about these issues, get familiar with boat values. I'm not referring to a sales term, but the published book values for used sailboats. I used the BUC values (see sidebar) while looking for my boat, but other guides exist, including NADA's. You'll notice that there are patterns in the prices for older boats; some, like MacGregors, are relatively inexpensive, while others aren't. Some prices drop over time; others don't seem to change that much. Whatever you do, avoid being an impulse buyer. There will always be more neglected boats available than people willing to fix them up, so in a sense, this is a buyer's market. The first thing you need to do when you see a boat for sale is look up the BUC value. This gives you a baseline idea of how much the boat is worth.

Remember that this is a baseline idea, not an absolute value. The real value of any boat is what a buyer will pay for it. In some areas, particular boats sell well above the book value, while others are at or even below the given figure. Outboard motors usually aren't part of the BUC value, and the replacement cost of an outboard can go as high as $1,200 to $1,400 for a new 9.9 hp. I bought a used 5 hp for $450. Keep in mind that a good or repairable trailer can have a big impact on the selling price as well.

The Self-Survey

Professional marine surveys are almost always a good idea, but for a small, inexpensive, trailerable sailboat, you may not need one. I make this claim for several reasons:

The cost. A competent surveyor will charge at least $300, and that's over half of what I paid for my boat.

The cost. A competent surveyor will charge at least $300, and that's over half of what I paid for my boat.

The type of boat we're talking about. Any neglected sailboat will have a plethora of problems, and most surveyors will tell you to pass on just the sort of boat that you're after.

The type of boat we're talking about. Any neglected sailboat will have a plethora of problems, and most surveyors will tell you to pass on just the sort of boat that you're after.

An exception to this would be if you can find a surveyor who is sympathetic to your idea of fixing up an old boat. Another exception might be if you don't have much experience in boat work, and you really have no idea of the extent of a vessel's problems. Or perhaps the boat is a long distance away, and a survey would be less than a plane ticket. In this case, getting a surveyor to work for you becomes a viable option.

If you do choose to do your own survey, you should become familiar with the art of fault-finding in boats. Ian Nicholson has written one of the few books available on the subject called Surveying Small Craft. Other books on boat repair and maintenance will give you an idea of the magnitude of work required for various jobs. One of my favorites is This Old Boat by Don Casey. Another good writer on this subject is Ferenc Maté, who wrote From a Bare Hull and The Finely Fitted Yacht. Though both these books deal with newer boats, they offer a wealth of information. I'm a big fan of boatbuilding, sailing, and cruising books; in the following chapter, we'll look at some additional titles you may find helpful.

With this background information in mind, I've come up with a list of potential "boat-killer" problems to watch out for. Remember when I said that nearly any fiberglass boat can be brought back? This is true in theory, but some of the following problems can result in a boat that takes far more effort than it's worth.

"Boat-Killers"

Structural Cracks or Holes in the Hull. Unless the boat is free—and even then—consider that this type of problem involves a major repair that may never look right. If it isn't fixed perfectly, you may never be able to sell your boat later. There are so many available boats without this sort of problem that it rarely makes sense to tackle this unless the boat is worth a great deal of money repaired (for example, a Bristol Channel Cutter or a Flicka). An article in the July 2002 issue of Good Old Boat magazine describes the replacing of a ten-foot section of hull from a sunken Hinckley. When completed, this boat will be worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, thus justifying some very extreme repair measures. But for most boats, you don't want to go there.

Missing Major Equipment. The replacement cost of a mast and standing rigging, for example, will often be higher than the value of the entire boat. Rudders—possibly even a keel—can be replaced. But it's almost always better to repair an existing part than to fabricate one from scratch, especially of you don't have a pattern. Likewise, a boat with a brand-new motor, trailer, or sails may turn out to be a bargain, despite the higher initial purchase price.

Extensive Wood Rot. While a small amount of rot isn't too big a deal, large rotten areas or water-delaminated plywood bulkheads mean a pretty major repair job. A telltale sign to watch for is a mud line near the cabin sole, where standing water has sat in the boat for a while. If this mud line gets

|

SAILING TERMS

|

|

The cabin sole is the boat's floor. The walls (the flat ones that divide the boat into front and back compartments) are called bulkheads, while the ceiling is called the overhead. In boatspeak, ceiling refers to strips of finished wood that are screwed to the inside surfaces of the hull.

|

|

Go figure.

|

as high as the bulkheads, they may be starting to delaminate. In an inconspicuous area, poke the wood with an ice pick or pocketknife. If the tip goes in easily, there's trouble, and that area needs attention.

A "Partially Restored" Boat. You'll need to know how things went together before you can put them back. If the boat has been taken apart, then it has a huge strike against it. Plus, you'll need to use the rotten pieces to make patterns (see Chapter 4)—this is hard to do if the rotten pieces have been thrown away. Very often, someone buys a boat, realizes the project is just too much, and decides to cut his losses. A situation like this might be worth investigating closer, but it will be harder to put the boat right. The seller should expect to deeply discount a boat like this; after all, you're doing him a favor by bailing him out. Remember: Arm yourself with knowledge before you take on someone else's nightmare. Sometimes, a knowledgeable restorer has unusual reasons for stopping a project and selling (a death in the family, for example), and you can pick up on a great deal. But cases like this are rare, so be careful of partial restorations.

Tools to Bring

Tools for the small boat surveyor are fairly simple: a notebook and pen, a finely-tipped awl or pocketknife (to check for rotten wood), and a flashlight or work light. A camera can really help refresh your memory later, but interior shots are hard to get correctly exposed. Inexpensive autoflash cameras aren't made for tight interiors and dark closeups, so use the best camera you can. A digital camera is the best choice, because you have the luxury of viewing the pictures right after you've taken them. Some people have used video cameras with great results; you can add a running commentary to refresh your mind later. After you look at a few boats, the details start to run together.

Where Do I Begin?

When I look at a boat, I like to start at the bilge and work my way up. There isn't much of a bilge on most small boats, so this means looking at the keel/centerboard area. Repairs here aren't necessarily all that difficult, but the weight of the keel plus the problem of limited access make repairs a big job. On my MacGregor, for example, the keel was made up of three plates of ½-inch-thick steel, welded together and

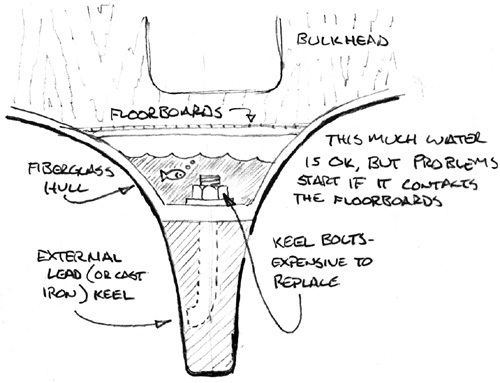

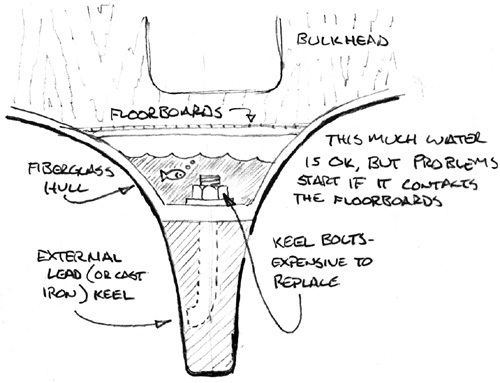

A fixed keel bilge. There's room here to hold the water that will find its way aboard, though the keel makes launching and trailering difficult.

encapsulated in polyester resin and fiberglass. The polyester failed over the years, and the plates began to rust. Rust expands metal, and the fiberglass skin had swollen the keel until it stuck inside the keel trunk. A previous owner had sliced away large sections of the offending areas, leaving the metal exposed when the boat was in the water. The only fix was to rebuild the keel from the metal plates up. The repair itself wasn't that complex in theory, but the reality of lowering the keel out of the boat and maneuvering it around was a royal pain. Some boats have cast-iron keels, making repairs much easier. If I had been able to find one, I would have replaced this keel with a cast version.

Blisters are a common problem with boats that are left in the water. Experts disagree on the exact cause, but water migrates into the fiberglass resin and collects in pockets that can be as small as a pinhead, just under the gelcoat, or as large as a quarter, forming deep within the laminate. They can even lift apart the layers of fiberglass in the hull, causing significant structural damage. Gelcoat blisters are mainly cosmetic but could indicate future problems if you're planning on keeping the boat at a marina. Large, deep blisters need to be dug out, thoroughly dried, filled with epoxy,

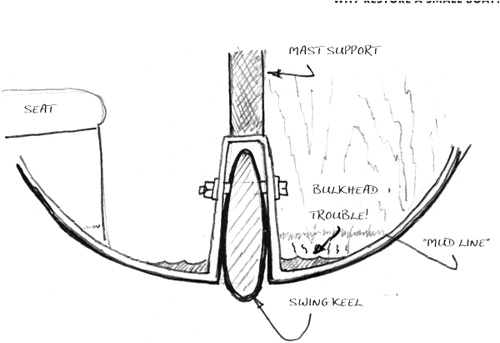

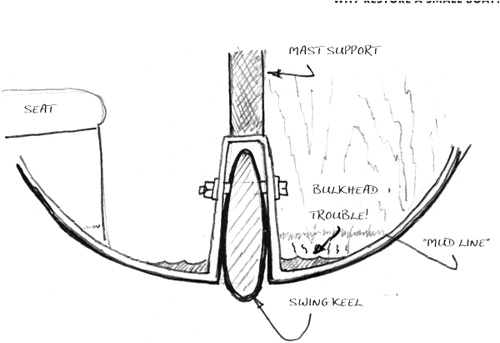

A swing keel bilge. Water collects by gravity in the lowest part of the boat. There's a far higher likelihood that any standing water will cause damage compared to a boat with a traditional bilge. This is one of the "trailerability tradeoffs."

and sanded. Then the whole hull needs to be barrier-coated with a special paint containing coal-tar solids or epoxies (such as Interlux's Interprotect 2000, which is epoxy-based, or VC-Tar Barrier Coat, which contains coal tar). Earlier repair practices of coating the entire hull with epoxy have in some cases made the problem worse. At any rate, the amount of work required to fix a badly blistered hull can be considerable. But if the boat is otherwise in good shape, this can be used as leverage to lower the purchase price. Trailerable boats seem to be less afflicted with blisters, as they are often stored on the trailer.

When you look at the interior, think low and inside: low down in the hull where the water collects, and inside all the lockers, covers, and hiding places. One of the things you're looking for is standing water, because it can cause a surprising amount of damage in a fiberglass boat. Standing water greatly accelerates rot in wood, delaminates plywood bulkheads, corrodes wiring and fasteners—it's generally bad news. If the boat has deep standing water in it, that's a sign of a careless owner, and you can expect to find much preventable damage caused by neglect. The selling price on this type of boat should be very, very low. Don't believe the often-chanted sales mantra, "All she needs is a good cleaning." In my opinion, no boat can survive an appreciable amount of time with water in it without suffering significant damage.

Now I'm not talking about a little water in the bilge. Boats with fixed keels or keel centerboards sometimes have a bilge beneath the floorboards. The bilge

|

WHAT ABOUT THE SAILS?

|

|

When you look at a potential boat to restore, pay particular attention to the condition of the sails. Get all of them out of the bag and spread them out on the lawn. I'm of the opinion that folded sails can indicate a conscientious owner. There's an argument that sails are better stored by simply stuffing them in the bag, because the wrinkles are never in the same place, but the sails are never folded exactly the same way each time, are they? Points off if you find the boat stored for the winter with the sails wrapped around the boom. More points off if the sail cover is in tatters or missing. Sailcloth is sensitive to UV rays, so a rotten sail follows soon after the cover goes.

|

|

Try to find out when the sails were made. If they're the original sails, you can count on replacing them unless they look really good. You want the cloth to be somewhat stiff and the stitching tight. The stitches are usually the first to deteriorate, so examine them closely.

|

is designed to be able to cope with a certain amount of water that will inevitably find its way aboard. Leaving standing water in the bilge might accelerate blistering, but, other than that, a small amount of water doesn't hurt.

Many trailerables with retractable centerboards or daggerboards don't have a bilge in the traditional sense. Instead, you stand on the lowest part of the boat and walk through any puddles that collect. A boat like this can only cope with a small amount of water before it comes into contact something that isn't supposed to be wet, like wood or wiring. So watch out for any water that'll get your feet wet as you look at the interior.

If you don't see any standing water down below, that's better, but you're not out of the woods. Now you're looking for evidence that the boat has flooded in the past. Usually, in lower-priced boats, a seller will pump out his neglected boat, but he won't take the time to clean away the evidence. What you're looking for is a mud line, a small dark band that forms at the top of the flood. Think, "ring around the bathtub." Look inside all the lockers, especially the ones under the quarter berths; these lockers are rarely cleaned out, even if the rest of the cabin is spotless and shiny.

If you find evidence of flooding, ask the owner about it. Show him the line if he denies it, and begin searching for water damage and rot below the line. Here's another chance to use your handy fine awl or a pocketknife. With the owner's permission, probe the wood parts to see if you can find any rot, but do it in areas that won't show. You may see marks where other potential buyers have done the same. Be especially suspicious if wiring was submerged, and doubly so if there are splices in the wiring that have been submerged. This can lead to mysterious intermittent shorts that are difficult to trace.

Now seems like a good time to talk about liners. Starting about 1973 or so, boat builders figured out that they could save a lot of time by installing molded fiberglass cabinetry inside a boat, rather than building the interiors piece-by-piece. These hull liners or hull socks, as they were sometimes called, fit inside the hull and cut completion time and material costs dramatically. This method of construction has some drawbacks, mainly the loss of access to important parts of the hull and centerboard. It can also be an inherently weaker form of construction, because the liners are bonded to the hull in fewer places than a piece-built plywood interior where each bond would add stiffness to the hull. But one of the big advantages is that less plywood and lumber are used down low in the boat. Thus, flooding isn't as serious a problem as it is in boats built without liners. Less wood means that the boat may do all right with a very thorough cleaning in cases of neglect (in other words, standing water). Even so, you still need to be careful; some liners are attached using plywood "tabs" that are bonded to the hull, and then the liner is screwed to the tabs to secure it. There's no way to inspect wood that's buried behind a liner in this way. If the tabbing is severely rotted, it could allow portions of the interior to come adrift in a seaway—not a pleasant thought. If the boat looks badly neglected, you should suspect this sort of problem, but otherwise a boat with a liner might be a good deal easier to restore than one without.