2 The Disadvantage of Being Left Behind—A Knowing–Doing–Learning Gap

Urban Luck Design, urbanluckdesign.com

Wisdom is to know what you do not know.

—Socrates

Teachers begin their careers at a disadvantage. Most professions require at least three to four years of undergraduate or graduate training. Diane remembers her nursing friends who were immersed in the field as freshmen. Later when she majored in speech pathology, she had to take a year of undergraduate courses before beginning an extended-year graduate program. Most other professions require three to four years of graduate studies. In the United States, however, teaching certification requires few undergraduate education courses and only one year of graduate work to receive degrees. Teachers are also required to attend a short-term student teaching experience which is mainly focused on delivering content.

Quite simply, one year of coursework in which a practicum counts as half is not sufficient to build a knowledge base for a profession in the 21st century. Teacher development in the United States stands in stark contrast to Finland, where teachers major in education as undergraduates and follow it up with a graduate program; Finnish teachers are required to obtain a two-year master’s degree. They must attend a university that is also involved in educational research. No wonder Finland is one of the best educational systems in the world; their teachers begin teaching with as much or more schooling than doctors, dentists, psychologists, and lawyers. We also recognize that Finland’s educational system did not happen overnight. It took planning and commitment to increase the effectiveness of their school results. Likewise, other nations have also made great strides in elevating teacher and administrator preparation. Closely aligned with professional preparation are salaries commensurate with their training.

Noteworthy to mention here is how this subpar certification process in the United States vests teachers with a false competence. Armed with a credential, beginning teachers enter the profession believing that they have had sufficient training, only then to discover that teaching is not quite so simple, causing many to leave the profession. Others who work well with children can become overconfident, swayed by their charisma with children. Diane recalls a fairly new first-grade teacher who was popular with students and parents; her class was fun. What was not evident to the untrained eye was that she really did not understand the scope and sequence of a robust reading program and had huge gaps in the learning progression. This showed up in reading test scores; some children made no gains during the year. Even though the first-grade teachers were given some training in reading, she had not applied what was taught. This is called the “knowing–doing gap.”

Closing the Knowing–Doing Gap

The knowing–doing gap, identified by Pfeffer and Sutton (2000) of Stanford, recognizes that as knowledge expands, the leadership challenge becomes one of how to turn knowledge into action. All professions require on-the-job learning, and the gap between knowledge and doing continues to be problematic in all professions. The “gap” identifies the paradox of inaction; even with knowledge, people will not act to change behaviors. In other words, exposing employees to knowledge does not produce the needed actions to operationalize knowledge. The belief that dissemination is sufficient to bring about change is a failure of leadership. Instead, the most important task of a leader is to build systems that facilitate the transfer of knowledge into action; taking time for professional conversations about practice best does this.

Pfeffer and Sutton (2000) found four problems that contribute to the knowing–doing gap that apply to schools. First, when “talk substitutes for action,” schools tend to have the same conversations over and over. For example, one teacher puts “school litter” on every staff meeting agenda. Even when a plan is finally implemented, most teachers take their students out once and then forget about it. Accordingly, an abundance of trivial items on any agenda saps energy and robs time that could be spent on more substantive talk.

Second, “memory is substituted for thinking” when schools continue to plan for rituals that are no longer important, such as carnivals, spelling bees, or award assemblies based on past history. In one district, an entire school refused to adopt the new mathematics curriculum because they liked the old one better. When queried, it turned out most knew next to nothing about the new curriculum. We coined the term contempt before investigation to describe this attitude.

A third cause of gaps is “fear that prevents acting on knowledge.” In the Introduction, we describe teachers who are afraid to speak up for fear of reprisals from peers. Yes, teachers can be our own worst critics.

A final cause of gaps is when “measurement obstructs good judgment.” Nowhere is this more evident than with high-stakes testing. It shows up in small ways when teachers let kids chew gum to relax during a test or throw a pep rally to reward high test scores. It manifests in tragic ways when well-meaning educators are caught changing answers to improve scores. Another problem with end-of-process measures is that the results come too late to inform action. Receiving last year’s test score as teachers return in August to begin a new year with new students has limited use for teachers.

From Knowing–Doing to Knowing–Doing–Learning Gap

Closing the knowing–doing–learning gap is not an event, but rather a process of continuous learning and reflection. Learning is an adaptive act, requiring ongoing reflection about what we are coming to know, and this knowing impacts “the doing.” For this reason, we prefer to use the term knowing–doing–learning gap. Joyce and Showers (2002), in their book Student Achievement Through Staff Development, studied the impact of professional development—specifically, imparting knowledge, demonstration, and coaching—and found that coaching conversations led to a 95 percent increase in learning. In other words, professional conversations have the power to close the knowing–doing–learning gap. By adding learning to this term, we signal our intention, which is to improve professional learning. For this reason, we have added a fifth impediment to closing the knowing–doing–learning gap, and that is the belief that “adult learning is private.” Learning should be collective (see the WISE report on Collaborative Professionalism by Hargreaves and O’Connor, 2017).

The lack of collective learning shows up in schools that reward competition; hence, teachers do not share or see the value of working with colleagues. These teachers view their teaching as sufficient and do not feel a need to learn from others. These schools tend to have favored teachers who get more accolades and attention from parents, students, and administrators. We have even heard teachers say, “I don’t want her to steal my ideas.” This attitude—that ideas are commodities that can be stolen and that popularity equals excellence—creates real barriers to the collaborative conversations described in this book. These schools in which teachers feel isolated or excluded create deep resentments that serve only to divide the staff further. It is a vicious cycle: The less we talk with our colleagues, the more we judge from limited information and the less we want to talk with them.

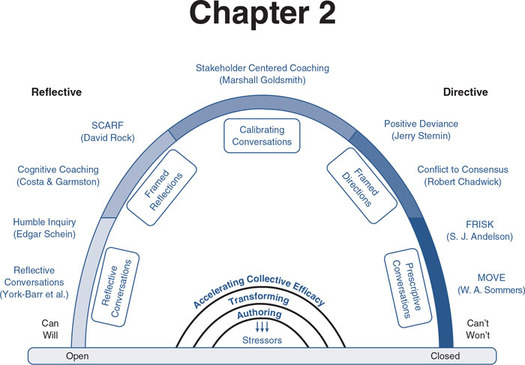

It is through collective conversations that groups change minds and improve practices. The conversations in this book help break down the barriers of fear. They move groups from talk to action. They challenge known assumptions and foster a willingness to explore. They help teachers learn ways to measure what they value, not what is mandated. Knowledge is important and insufficient; doing requires action; and learning is the end product and becomes collective when these processes are shared. We believe a popular aphorism about Las Vegas should be reversed in education: “What goes on here, leaves here—in fact, shout it out.”

Short of a major overhaul to training requirements in the United States, it is essential for the profession to take responsibility for filling in this knowing–doing–learning gap. This capacity building cannot happen in isolation or from mandates from the outside; it does not happen from fragmented, irregular professional development. It is not uncommon that as teachers come to know more collectively about how to best meet the needs of students, they become angry—why hasn’t anyone addressed this issue before? This failure that leaves teachers behind is evident throughout our school systems. As an antidote, this book offers capacity-building pathways through the morass in order to build relationships so that teachers can improve professional skills by examining capabilities, values, and beliefs.

Reflection

A Place to Pause

iStock.com/BlackJack3D

- ■ How do schools bring new teachers into the profession?

- ■ How do schools enrich the professional lives of veteran teachers?

- ■ How can we learn from newer teachers with good ideas?

- ■ How can we learn from the experienced teachers and administrators?

- ■ How can veterans pass on their best knowledge and reevaluate what is not working? How can this knowledge be used to support new teachers?

Building High-Capacity Learning Communities

Capacity, as defined here, is a developmental construct in large part influenced by personal mental models about learning. Those who demonstrate high-capacity learning are adaptive and focused, yet flexible—always inquiring and paying attention to personal assumptions and knowledge gaps. These teachers seek challenges that pique thinking and allow for adaptable, professional knowledge creation. They continue to learn and create even through retirement and often beyond. They value collaborative learning and seek it at every opportunity. They inspire others.

The educational community needs to find ways to open access to conversations and to create regular graduate-level conversations in which knowledge is gained, created, and practiced in context. In many systems, professional development is often taught in a manner familiar to most undergraduates—listen and get knowledge. This type of learning may be essential for foundational learning, but once the foundation has been established, learning needs to be more personalized and nuanced. The learner needs to be able to engage in intellectual dialogue and practice-based learning. This idea is not new, but it has been difficult to sustain. Bill tells how such a program was life changing.

Bill describes his first encounters with Art Costa in 1983 at an administrative workshop on the topic of thinking skills. Not only was his curiosity piqued by teaching thinking skills to students, but he also became interested in some of the research cited by Art. After the workshop, Bill read one of his first professional books since college (his humble confession). Most startling for Bill was the realization that there was a vast knowledge base about teaching and leading accessible to him through books. Anyone who knows Bill knows he reads and summarizes at least one book a week and shares these summaries widely; he even finds time in Hawaii to continue this daily ritual. An avid reader, he summarizes what he reads and shares these with hundreds of educators, building his own personal legacy (see a sample at www.learningomnivores.com and “Sommers Summaries” on Chris Coffey’s website at http://christophercoffey.com/upcoming-events/).

Later, when Bill became a trainer for a summer institute, he began to appreciate even more the unique design of this program. The participants split their time between learning new knowledge and practicing this knowledge in classrooms with children. They watched each other, reflected, and learned together. Bill continues to share a professional relationship with some of these people all these years later. As Bill reflects, “This immersion in compelling ideas and then the application of this knowledge in the classroom, followed by reflection on those practices, was new to me. I was hooked.” Indeed, Bill goes on:

I would never have been in a place to be a leader or to write this book if I had not taken that workshop all those years ago. It was as if a screen had been lifted as I came to a realization that continual learning is essential for professionals.

He laughs when he thinks about how one of Art Costa’s questions gave him fuel for thought for the next school year. Art stated, “I am more interested in what kids do when they do not know the answer, rather than when they do know the answer.” This question shifted both Bill’s teaching and leading. Others noticed, and Bill moved into administration when his principal tapped him on the shoulder and said, “Have you ever thought about being a principal?” His first answer was no. A year later, he was an administrative intern.

The Illusion of Control Over Student Learning

For efficiency, as schooling in the United States became compulsory, schools moved from one-room schoolhouses to clustered grade levels based on age and to larger, comprehensive high schools. This allowed teachers to specialize in the pedagogy of a particular age grouping or in the content domains. While grade-level grouping and departmentalized high schools have many advantages, they also have disadvantages; the most significant is the lack of continuity for children. All these groupings create the silo effect—the creation of artificial boundaries that serve specific needs and ignore others. This means that elementary teachers become grade-centric and secondary teachers become domain-centric, and collaboration often stays within these boundaries. The conversations in this book assume that these barriers need to be broken down.

The truth is that without professional conversations, curriculum implementation in schools will never be even. Policy makers and many administrators believe that textbooks bring alignment and fidelity. However, unless teachers are provided with quality conversations about the implementation of any program, the idea of fidelity is an illusion. Often during the first year of a textbook adoption, teachers spend time grappling with emotions tied to letting go of the “tried and true” and the mechanics of this new adoption. It is only over time that teachers get to the essential question: How is this making a difference for my students? And many schools never get to this question, leaving each teacher to answer the question and find his or her own pathway through the adoption. It is not unlike a well-manicured park: Early on, most will follow the path, but over time, some take shortcuts, making new pathways and changing the landscape. Likewise, over time, teachers even in the same grade or department can have wildly different curricula with the same textbook.

The essential question is not about fidelity but about how any curriculum makes a difference for children. By working together to explore the goals and strategies of a new curriculum, teachers begin to participate in collective reflection about practice. They begin to find points of coherence. They share successes and failures and build a robust understanding of how students learn in relation to the adopted materials. Diane used to tell her teachers, “We have paid a lot of money for this new board-adopted curriculum. Your job is to understand the new curriculum and to ask how it makes a difference. If you think you have a better way to teach something, we need to take time to understand what you are coming to know.”

When curricula are developed in this way, teachers grow together rather than apart, and they speak with one voice, which is both confident and adaptive, demonstrating collective efficacy. Diane saw this firsthand when she hired eight new teachers to implement class size reduction in the primary grades. She observed a startling contrast between classrooms during the first year; some of the new classrooms were full of books and materials and looked like all the others, but some seemed empty, like her own classroom in her first year of teaching. It turned out that the first-grade team had knowledge coherence about literacy instruction and were quick to share materials, lesson plans, and support with the new teachers. The other grade levels had limited coherence, and as a result, the new teachers were left on their own. Without realizing it, one group of teachers demonstrated the importance of collective efficacy. They also had created a knowledge legacy without even realizing it; they worked collaboratively to pass down what they knew to the newcomers. In the other classrooms, the teachers were truly newcomers left to forge their own pathway.

For some, the concept of collective efficacy seems like an elusive dream because the teachers they work with do not agree. We would argue that in the face of disagreements, it is even more important for these teachers to learn how to participate in the Nine Professional Conversations outlined in this book. These teachers need to find a coherence—an understanding of what they agree about and what they are going to agree to disagree about. For us as authors, it is essential that the reader understand that speaking with one voice does not always mean agreement—it means speaking from a coherent understanding about how teaching impacts learning. We both have been successful at building productive relationships with unions, and this requires that both sides know where they agree and where they do not agree. While it is not covered in this book, interest-based bargaining sets in motion very specific types of conversations, which when done well bring this same kind of coherence.

The Cliché: Children Are Still Left Behind

The real problem, however, with the lack of coherence across and between grade levels is the uneven experience offered to students. Students who struggle stop working from fatigue; those who are successful persist and puzzle through what they do not understand. When the pedagogy changes from grade level to grade level, students who lag begin to fail repeatedly. In secondary schools, this problem is compounded when failing students are siloed into remedial classes that have nothing in common with what peers at the higher levels are learning. In one local junior high, English language learners are required to take two periods of English but lose out on a year of social studies. Common sense dictates that the English and social studies teachers, with the proper support and collaboration, could create a curriculum that better serves these students. It may be cliché: School curriculums, thoughtlessly implemented, can and do leave children behind.

Diane experienced this lack of continuity firsthand as a superintendent. As she grappled with the high costs of educating special needs students, especially the cost of outside referrals, Diane began chatting with special education staff. One specialist mentioned the large numbers of students in intermediate grades being referred for occupational therapy for handwriting. The resource specialist was emphatic: “If we taught handwriting in our schools, this would not be a problem!” New to her job, this was just the opening Diane was looking for to begin a series of conversations about literacy instruction.

Diane thought (mistakenly, it turns out) that handwriting would be a low-threat conversation. She soon learned that the gaps were huge. Handwriting in many classrooms had been left to happenstance, and those classrooms that did attend to writing were using a variety of outdated methods. The resource specialist had been correct; over the years, handwriting instruction has been eroded. While handwriting to some might seem less important, it exemplifies the fragmentation that occurs when teachers are left alone, and in this case, it had economic implications for a district already strapped for funds.

Seeking Coherence in the Curriculum

For schools to seek coherence in curriculum design, teachers must have quality time to codevelop a curriculum that builds one element upon another and that provides integrated, articulated learning programs. A learning consultant once told Diane that for teachers to meet the needs of all students, teachers require an understanding of five grade levels—the two before the one they teach and the two after. Likewise, at secondary levels teachers who know how thinking patterns enhance or limit student learning are able to better accommodate all students and link courses across the domains. They would never suggest that students lose an entire year of social studies in the service of learning English!

Armed with this knowledge as a superintendent, Diane began insisting that district-level collaborations include more than one grade or department. The questions were always these: What is going on here? How is what we teach the same and different across the levels? The payoffs were profound. At the elementary level, teachers found gaps in their teaching strategies. Depending upon when they had been trained, they had entirely different ideas about the difference between phonics and phonemics and even how to teach these skills. By coming together and talking about how they teach reading, they found a coherence, and it changed forever the way some teachers worked.

An example of how to do this at the secondary level would be to have one department, such as math, work to build bridges with science, economics, and even the statistics collected by PE teachers. And in the converse, other subject areas should also work to build bridges to the mathematics curriculum. When students experience these connections across a curriculum, they experience the coherence of learning—everything is connected.

There is no subject better served by these cross-pollinating discussions than the teaching of writing. When Diane brought teachers together to probe into current practices, the teachers in intermediate grades were amazed to learn that their primary counterparts were teaching basics, which were then retaught at every grade level. The question became not of what we teach, but how do we hold students accountable for what they have learned as they travel through the grades. Writing is hard work, and without an accountability system, the students had tended to slip to more immature work patterns. A special education teacher created a simple rubric that students could use to maintain expectations. This ended up being the first of many conversations about writing.

When teachers work to find knowledge coherence for a discipline or across disciplines, they begin to speak with one voice. They find that their differences often are not as great as they thought and that many times points of divergence yield the greatest breakthrough in understandings. When they do disagree, they understand that it is nuanced and that both ways produce results for students. Confident in their knowledge, they not only help students understand how learning connects, but they also help parents—and school boards such as the one described in Chapter 1—better understand changes in curriculum. Knowledge coherence requires that teachers talk, debate, argue, and challenge each other to find the deepest truth about teaching that they know. This in turn guides the teaching practices of a school in a coherent way. When this happens, teachers create knowledge legacies that are shared, and new teachers benefit from the wisdom of the elders. Leaders focus less and less on control and more and more on how to close learning gaps and increase coherence within and across the grades.