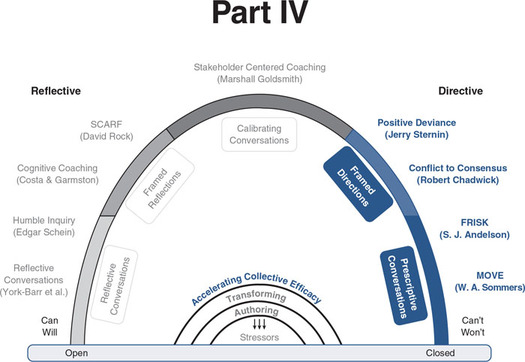

Part IV Conversations Designed to Build Knowledge From the Outside In

Urban Luck Design, urbanluckdesign.com

As authors, we write to learn. Writing in itself, particularly this kind of a book, is a reflective act. As we grappled with what we were trying to say, we had our own breakthroughs and came to a deeper understanding about our own knowledge. Early on, we agreed which types of conversations we wanted to include and the sequence for the types of conversations we would offer. What was more difficult was making explicit why we had made these choices.

We also confronted an unexpected challenge. When we showed our colleagues the Professional Conversation Arc, they were quick to want to make it a diagnostic tool. As leaders, they somehow seemed to think that it was their job to choose where to start on the Dashboard. They wanted to use it to prediagnose the other person or group and then choose where to intervene—in other words, they wanted to be directive. This puzzled us, and we struggled to figure out why we were so adamant the process be left open to choice—even though we present a continuum, it is not a diagnostic tool. The Nine Conversations are a collaborative leadership tool designed to expand repertoire for responding to real issues in real time. We hope this is clear to the reader by now.

The biggest breakthrough came when we realized that most conversations in schools really do not live on the Dashboard at all. In fact, if the arc were the top of a clock, most conversations in schools would start at about 1:00—somewhere just beyond Stakeholder Coaching. By this, we mean that most public conversations—and we include all professional development—start with someone making a determination about what others should know; hence, that is what is focused on and talked about. Even when teachers are involved in making choices, it is often a small group who decides for the larger group. The point is that most conversations are not reciprocal, but are designed to impart information and give direction so are more unilateral. While some of this type of work is necessary, these unilateral conversations should not consume all available time for collaboration. Indeed, in our view, these conversations should be organized around teachers’ understanding of their own knowing–doing–learning gaps.

We also include much of the data focus of PLC work in this unilateral approach. Even though teachers are collaborating, the focus is often test scores, benchmark assessments, and other forms of data mandated by others. The problem we have learned is that these are constructed data sets that often bear no relationship to practice. Diane tells the story about how diligently she worked with teachers to analyze state-mandated assessment data. She reflects,

To be sure, we collaborated; but in the end, we gleaned little useful information for the classroom. While it was an interesting intellectual exercise, it gave no guidance to practice. Quite frankly, the teachers told me that they already knew who struggled. They were right; after all that work, most of the time our conclusions were that we needed to improve reading comprehension or basic math concepts.

Diane finishes, “My regret is that I made this mistake at least five times—every time we had a new mandated test.”

Bill tells the story of secondary teachers spending all their collaboration time designing benchmark assessments to monitor progress in algebra. One teacher later said,

You know we did all that work and were so proud of it. The problem was that in the end we still did not really know how to reach those kids who just do not get it. We would have been better off trying to figure out how to teach those students differently.

What was startling for us was to think how long in our careers we lived by these expectations—that somehow these external directives would hold the solution. We had mistaken data study for action, but could not develop operating instructions. This is why we expanded the knowing–doing gap with learning.

We know, we do, and we learn, which sometimes means we modify our actions. We would have loved to know earlier in our careers the piece of Hemingway advice: “Never mistake motion for action.” We have seen lots of motion in our long careers and occasionally refer to it as the “reverse butterfly effect.” Remember that a butterfly effect means that small changes produce large results. A reverse is when huge expenditures of time and money result in small or few results. We were lucky—and persistent—and found a way out . . . hence, this book. And, we are still learning.

Part IV could be a book in and of itself, but that is not the kind of book we wanted to write. After all, most of us have become experts ourselves in planning for professional development delivered by content experts or in facilitated processes using protocols. For the purposes of this book, we have picked two specifically Framed Directive Conversations by way of example. What is important here is that in most cases, one person, or one small group, has decided that something needs to change. In the case of Positive Deviance, a failure needs to be reconciled. In the case of Conflict to Consensus (the Chadwick Process), the parties are in an intractable conflict that inhibits progress and needs to be resolved. Both are unique processes and are strategies that come from outside of education.

Finally, we finish the continuum with two Prescriptive Conversations—conversations that confront issues head on; yet they still require listening, reflective thought, conversational skill, and humane treatment. These conversations require due process, a chance for the other person to know and respond to the claims. When used appropriately, due process is invaluable in giving both sides another chance to be heard. It also helps the supervisor ascertain when the person is unable or unwilling to keep a commitment to do better. At this point, lip service or excuses are not acceptable; when responsibility for change is not forthcoming, the signal is clear that this is not the right time or place for that person. So join us in rethinking how we frame change and give directives that allow for a return to reflective thought.