12 MOVE—Time to Move On

Urban Luck Design, urbanluckdesign.com

I would have preferred to carry through to the finish, whatever the personal agony. . . . But the interest of the nation must always come before my personal considerations.

—President Richard Nixon’s resignation speech

What do you do when nothing seems to work? This is the question that most leaders worry about. The fact is that every strategy we have proposed will work. The truth is that every strategy we have discussed won’t work. Remember, there are NO silver bullets.

Having said that, truth telling is challenging. Having the courage to confront teaching and leading that is less than effective is difficult. Leaders are constantly balancing expectations and actions in the belief that we can figure out the puzzle of learning and leading and supervising for improvement. When adults fall back on the tried and true, assumptions are not examined, and learning is most certainly not happening in a way that makes students successful. Progress becomes elusive and schools languish, attempting to make course adjustments that ultimately fail their students. The leader’s responsibility is to kids, but ultimately, leaders must deal with the adults.

Having progressed to this point in the book, as a leader you now have many ways to engage individuals and groups. You have been introduced to a multitude of approaches for creating meaningful conversations. You also know that your job is to engage constituents in deep conversations about practice. This lens expects that professional collaboration can be used to measure success. When communities engage in deep collaboration, those that do not engage are easy to pick out. When you notice that it is not happening, a tough decision lies ahead.

As always, the first question to ask is “What evidence do I have that this person truly wants to learn and change?” Obviously, when employees admit to their failings, then the discussion can turn to what is getting in the way. This opens the door for counseling or other support services that might help get mental health support or even point them toward a new career. It also allows the administrator to start the process of making sure that the employees know how serious this is and that their job is in jeopardy. We have both seen employees improve when faced with this dire consequence.

Unfortunately, changes at the last minute are often too late. Diane tells the story of a special education teacher who had terrible relationships with children. Together, she worked with Diane on some strategies to improve her rapport. It was slow going and took much of Diane’s time. By law, Diane had to give her notice of termination seventy days before the end of the school year. After that notice, the teacher completely changed the way she worked with the children. The change was really quite remarkable in how the fear of losing her job made her pay more attention and make changes. As Diane thought back on this experience, she realized that perhaps this teacher had a future, but it would not be in that district. Once the school board had taken action, she needed to follow through. Bill also adds, “When you have to whack employees over the head, they probably need to move on.”

Let’s face it: The work of leadership in schools is tough work, and despite our best efforts, we can alienate people when we tell them they do not have a job. These same people can make our lives miserable, and the worst part is they take far too much of the leader’s time. Sometimes in schools, we live with problem employees because their failings are elusive. Despite our best efforts, the changes made are minimal, yet there does not seem to be sufficient grounds for termination. This is a problem of mediocrity. We admire a principal friend who chose to transfer, knowing that another leader could accomplish some of the things she had not. She stated,

I decided to ask for a transfer after nine years. I am proud of the changes we made early on, but there are some folks who didn’t come along. At this point, I am not going to change them, and it is time for someone else to try.

When—despite your best attempts to be increasingly clear about expectations—there are still missteps and when you have provided data to document the failings, it is essential to move to the next step. In the face of evidence that the feedback is not being received in a constructive way, the leader must assume that person is not capable or willing to make the necessary changes. As Einstein and others have said, “If you always do what you’ve always done, you will always get what you’ve always got.” Without the courage to confront adult failings in the name of students, not much will change. Before giving up or shutting the door, here are some options.

MOVE

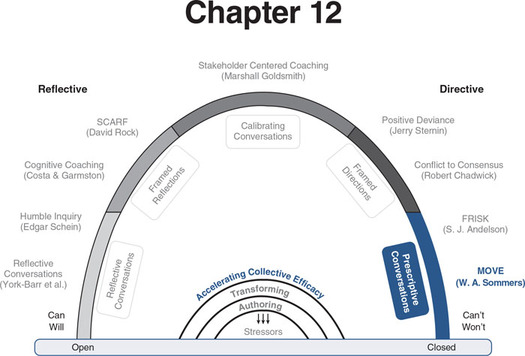

Bill loves acronyms and developed MOVE as a way to think about the next steps in a tough process. It allowed him to take a few humanitarian steps before finally saying good-bye. The first step is to decide if any kind of a move, such as a transfer or other option, is viable. As an intermediate step, the administrator should work with the personnel director to consider options requiring district support. Sometimes a leave of absence can give an employee a chance to make changes in his or her personal life or seek medication or counseling. When all else fails, it is time to confront the problem directly through termination and say, “You are done.” Before finally saying good-bye, though, there are steps that Bill takes in considering other options (see Box 12.1).

Box 12.1 The MOVE Process

M—Move to another assignment.

O—Outplacement; consider other job options, including career counseling.

V—Voluntary or involuntary leave: Will this help?

E—Exit the problem by moving for termination.

The first option is the candid conversation in which you as a supervisor return to previous conversations such as FRISK and revisit the lack of progress being made. The humane next step is to inform the person that her or his job is at risk and then ask, “What is keeping you from accomplishing . . . ?” Then listen. At this point, the person might become defensive, creating less-than-pleasant circumstances. When the person only attacks the supervisor and blames him or her for the failure and is unwilling to take any responsibility, the path is clear: It is time to move on. A less obvious but also equally damaging response is an attempt at sabotage, which manifests as ignoring the supervisor and going out to try to divide and conquer by getting support from friends. This is also a signal that no changes are intended. Before final termination, consider the following intermediate steps.

Move to Another Assignment

The leader with positional authority has the right of assignment in most districts. Sometimes, a staff member is not doing well in one situation, and moving to a new area might be better. Change in venues can help a person regroup for success. We have seen this work in moving a teacher to a different grade level in elementary school, to another department in middle school, or by changing the teaching assignment in a high school setting, all assuming proper certification. This is predicated on the belief that you want to keep the staff member in the organization, and she or he has qualities worth keeping. This should not, however, contribute to the system failure sometimes called “shifting the burden” or, more crassly, “the dance of the lemons,” in which failing employees are just moved around an organization.

For example, it became evident to Bill that an experienced (over thirty-five years) social studies teacher was not keeping up with the new curriculum approved by the board. He was very good person, a stellar community member, and was well liked by other teachers. The problem was further complicated by frequent complaints from students that his classes were boring, and the numbers of kids taking his advanced class were dropping each year. He always had a complaint or an excuse about why he could not address the issues. Bill was able to move him to an in-school suspension position (no loss of pay) using right of assignment—not an easy decision, but it needed to be done. This was done with the cooperation of the HR department and the superintendent. It gave this teacher the extra years he needed to maximize his retirement earnings—certainly a humane thing to do.

Being nice is not a leadership act; being thoughtful and fair in the service of students is. Bill knew it was the right decision when he was able to bring in an experienced replacement and the requests to take the AP class went up 30 percent. Within two years, they needed to add another teacher to handle the increased requests.

Offer Outplacement Services

There are times when a leader consistently is aware that staff members are unhappy with their own performance. They would like to change careers or go back to school, but taking that step is scary for many reasons. Districts are well served to offer some recompense to help this person move on. Offering outplacement services can be a positive step for the person as well as the school and has a positive, humane effect on the culture. We also have negotiated this process when there have been budget cuts resulting in staff reductions.

Here is an example to consider. Diane had a teacher involuntarily moved to her school; it was to purportedly to give her a second chance and allow her to receive some extra coaching from a vice principal. Early in the year, it became evident that something was not quite right. While her teaching seemed satisfactory, she rarely got through a week without an angry outburst from one of her students. Finally, the vice principal got a chance to see the problem in action—actually, the problem for this teacher was inaction. When a few students would start to act up, she was passive and used a voice that lacked command. Then other kids would jump in and try to control their peers’ behavior; soon, the class was riled up. Even with coaching, this teacher seemed to be unable to change. Finally, Diane asked, “What is keeping you from being firm?” She began to cry. It turned out that her father had been abusive, so she never wanted to raise her voice with kids. In her case, she belonged to a church that had a preschool position open. The vice principal knew of this position and suggested that perhaps she consider taking an assignment with younger children. She applied, was hired, and actually did quite well with a more open, less structured environment with younger children.

While we have not seen it happen often, from time to time our districts have also offered employee support programs, and these have helped teachers decide to retire early or take a leave of absence to get more training. The Minneapolis Federation of Teachers, under the leadership of Louise Sundin, had a program in which the union would assign a mentor teacher to work with staff that were having difficulty in the classroom. In California, the Peer Assistance and Review Program became part of contract language and offered similar support. In some cases, these programs made a huge difference for an employee; in other cases, there was no difference at all. They did provide constructive ways to offer assistance before termination was considered.

Voluntary or Involuntary Leave

Although rare, occasionally staff members will leave the organization, either temporarily or permanently. In most cases, if they are honest with themselves, they report that they are not feeling productive, know they chose the wrong career, or personal issues are causing a decline in effectiveness. When not motivated by a job, it is better to find a new career that generates some passion, energy, or commitment.

Our example here comes from a friend who describes how a principal was handled in a district. The principal had served for many years, but over time, the mistakes he made had built up enough that he had no respect from his teachers. It is important to note that he was a nice man and that the teachers liked him and enjoyed his humor. They just did not respect him as a leader. When the board tried to terminate him, the teachers rose up in alarm—they correctly perceived a lack of ongoing support for improvement from the board. The board backed down, and the principal went back to the school—nothing changed. Fortunately, a new superintendent came in with many years of experience in personnel and found an elegant solution. The teacher had skills with technology, so he was asked to take a partial leave from the principalship and work part-time to build the technology capacity of the district. As part of this plan, he would job-share with a retired principal, who would also provide him with some coaching. Unfortunately, while the technology job was a good match, the district did not have funds for a full-time positon, and he did not make much progress in improving his relationships with the teachers, despite the coaching. It was time to move on. Once again, the principal thought he might be able to get the teachers to back him up; they refused. He had been given a more-than-fair chance to improve, and he had not changed his behaviors. He finally agreed to resign instead of being terminated. As one teacher put it, “Fair is fair, and he did not take advantage of the help.”

In another example, a very dynamic, popular teacher showed up after summer break sporting a new, countercultural haircut. To make matters worse, his behavior seemed erratic. One week into the school year, he suddenly panicked, turned his class over to another teacher, and left campus without checking out through the office. By that time, parents and teachers had started complaining about bizarre behaviors. Some students reported that the teacher frightened them because of his loud, erratic outbursts. The personnel director chose to put him on immediate paid leave and forbade him to come to campus during the leave. As part of the process, a FRISK notice was given, both verbally and in writing. The principal was perplexed. How had this dynamic, creative teacher become so irrational? The teacher insisted that there was nothing wrong and was belligerent in the meeting. The following week, he showed up a block from the school, handing out copies of the letter from the personnel director on one side of the paper and his statement of dismay about his treatment on the other. Needless to say, the parents were relieved that he had been “locked out of the school,” to use his words. Finally, the teacher’s wife showed up in person and told the real story. She had married an amazing man, and until that summer, he had been a loving husband and father. She was aware that he took medication, but she did not fully appreciate how important this medication was for his mental health—he had been diagnosed as bipolar. Together with the wife, the personnel director confronted this teacher; he needed medical help, and if he did not get control of his life, he could possibly lose his job. This entire episode ended happily, but it took this teacher most of the school year to get his life under control. He went back into the classroom later that year and has been successful to this day. Not only did the leave give him time to rebalance his life with medication, but it also saved him from sabotaging his career. Parents were aware of the problem, but because it was handled quickly and effectively, his behavior did not become the lore of gossip. When a reputation is ruined, teachers need to change schools, grade levels, or districts to get a fresh start.

Exit the Problem by Moving for Termination

When students aren’t learning at the level they should be and there has been little cooperation in trying to improve, parting company is the best alternative. After reading this, you might be thinking, “Yikes, this is the hardest conversation.” Remember, you are dealing with a very small number of people. In over forty years of administration, Bill has removed only four teachers before the end of the year; Diane has been a bit tougher because of the short tenure period in California. However, only once did she remove someone before the end of the year. Caution: You must have district support before you take this step. And at this point, there should have been multiple conversations, so it should be no surprise to the staff member.

A Word on Termination

There is another E that will need to be addressed—Evaluate. Without a proper progressive evaluation process, the removal process will not seem humane. There was a time in California when teachers in the first two years could be let go for “no cause.” The lawyers often advised administrators to give no input—to just say, “Things have not worked out.” Diane remembers how crazy this made some teachers; they could not understand why the district was letting a good person go. Instead, in Diane’s district they decided to pick the one area that stood out and use that as humane explanation for termination. It was amazing that a clear statement such as what follows calmed them down: “We have worked hard on student discipline this year, but you still have too many problems with students.” Think about it; don’t we owe it to others to at least leave some door open for improvement? After all, they will go on to seek other employment. We do no favors by denying information that is evident.

There are times that the four steps of MOVE do not work, and formal termination is required. Personnel directors and legal advisors will often tell administrators they have not done enough evaluation. As leaders, we do not get to make a decision based on “no data” or limited documentation. Yes, paperwork is cumbersome. Yes, evaluation takes time. Yes, we would rather not have to go to these lengths, but we must. This is a leadership responsibility and obligation to students, staff members, and society as a whole. As a colleague of ours, Skip Olsen, former business agent for Minneapolis Federation of Teachers, said, “We don’t want bad teachers in the schools either. We want to ensure the process is correct. Make the case for removal. Don’t expect to make an arbitrary decision.” Good advice, and it is part of our job description.

In our experience, working the process using FRISK and MOVE in an unemotional way is perceived as a humane way to do business. We all are compassionate and don’t want to hurt anyone; this allows for both compassion and a steadfast commitment to serve in the best interest of students. Bill once had a union representative say, “I hate to lose a teacher, but I also know how much time you have spent trying to help and change teaching behaviors. It is the right decision.”

We know that at some point nothing is going to work. There may not be support in the administrative levels above, or there may be political situations that make removal impossible. At that point, we recommend going back to FRISK and MOVE strategies. Continue to hold this person accountable, and do everything you can to make the situation better or build the support needed to move her or him on. On a positive note, your best teachers know that protecting inefficiency or incompetence does not help them in the school or the community. The willingness to confront hard issues turns out to be a positive cultural intervention; it sets a benchmark for high standards. Use these strategies wisely.

Reflection

A Place to Pause

iStock.com/BlackJack3D

While personnel issues are confidential, most school staffs are aware of problems with peers and almost always know something about the interventions being made by an administrator. When you are aware of administrative action that may result in MOVE, how do you work with the affected peer? Do you sympathize? Do you avoid? Or do you “bear witness” (support the colleague without rescuing)?

Think about it: If you were in that situation, you would want to know that your peers cared. Here is a way to engage in a reflective, professional, and supportive conversation.

If you engage in this kind of conversation, do not sympathize; simply listen, paraphrase, and let the person know you care about him or her as a person.

- ■ “I sense that you could use a listening ear right now, would it be helpful to talk confidentially with me about what is going on?”

Then, if appropriate, try probing further with questions that keep the person focused on what she or he might do.

- ■ “Wise counsel once told me we learn most from our missteps. What are you learning during this tough time?”

- ■ “What might you learn from this experience that would help you in the future?”

- ■ “At times like this, it can help to focus on what we do well. What is it that you’d most like to focus on in these next few weeks with your students?”

It is helpful to separate the issues by stating what you can and cannot do. (This is especially necessary if you have been a mentor or a coach for this teacher.)

- ■ “I can’t really help you with this problem, but I can be here to allow you to reflect out loud with me about what you are experiencing.”

If any of these probes are rebuffed, stop. The intent is to be there for the person, not to fix him or her.

Final reflection: How might these kinds of interactions make a difference for a school culture?