Appendix

Creating Knowledge Legacies With Micro-Teaching and Visual Anchors

Diane often solves problems of group dynamics by teaching her staff a micro-skill she has picked up from her readings. By creating a visual anchor as a reference, complex concepts are broken down and visually represented so that this micro-skill can be applied in staff meetings. She describes the context in which she taught her staff two micro-skills here.

The power of these useful reminders was brought home when she used them to frame the conversation with the superintendent as described in Scenario 2 in Chapter 7. Her instructions based on the two graphics were clear to her staff. She told them to first seek to understand, and then to think about these two things as they related to the charts:

- Balance paraphrasing and inquiry with advocacy. (Chart 1)

- Remember that your responses will be at the initial levels of concern. (Chart 2)

When it came time for the appointed meeting with the superintendent, several of the teachers brought these graphics to the multipurpose room and posted them behind the superintendent. Diane laughs, “I do not think the superintendent ever noticed them, but he did notice that the staff were unusually sophisticated in their approach to the conversation.”

Balancing Inquiry With Advocacy (Chart 1)

As a young principal, Diane inherited a more senior, strong-willed, and fiercely independent staff. They set high standards for themselves and expected everyone to rise to these expectations. At staff meetings, a few tended to dominate. In order to help them learn to listen more to each other, she took about fifteen minutes to introduce them to a concept she had learned from Peter Senge (1990). As a way of teaching, she first drew the diagram the way Senge drew it in his book (no paraphrasing), and then she added paraphrasing (from her Cognitive Coaching work) to the mix and showed how it further tips the scales toward understanding and increases the power of the conversation. She then had the staff practice this new skill with an issue already on the agenda. The new graphic stayed up in the staff room, and from time to time, she would recommend on an agenda that the conversation about that item would use the tool Balancing Inquiry With Advocacy.

Balancing Inquiry and Advocacy

Source: Diane Zimmerman. Adapted from research in Senge, P. (1990). The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York, NY: Currency. Image source: iStock.com/iarti

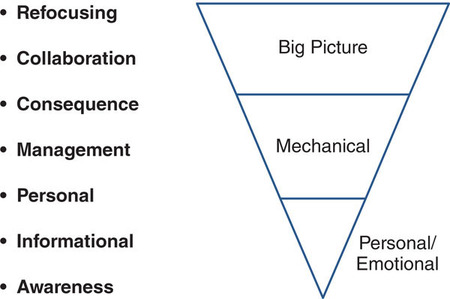

Concerns-Based Adoption Model (CHART 2)

When Diane first assumed the role of principal, she noted that her staff struggled with many mechanical problems that impacted their ability to teach. Teachers did not use the new computer lab because they did not understand how to use it. Several teachers spent precious instructional time cleaning acetates for a now-antiquated piece of equipment, the overhead projector. They often complained that there was not enough of a new set of math manipulative to go around and so forth.

Even more insidious was their “culture of complaint” about anything coming from the district office. Each time Diane put one of these items on the agenda, she would expect emotional outbursts from some of the staff.

As a way of helping teachers better understand the process of adoption and innovation, Diane taught them about the Stages of Concern (1990). As she told her teachers, the most important question we each need to ask is about impact: “How does what I am teaching impact my students?” She explained that when teachers get bogged down in the early stages of an adoption, they forget this aim. Diane challenged them by saying, “If we pay attention to these early levels, we can accelerate our adoption and are then in a better position to evaluate the efficacy of our work.”

Diane’s initial reason for introducing this concept of change was to help them self-diagnose the mechanical problems that were keeping them from excellent teaching. She used the example of the acetates and offered to work with teachers who were using the overheads to come up with a solution. “Ironically,” Diane states, “it turned out the entire staff was interested. Many had not chosen to use this tool in their teaching for just these mechanical reasons. Overnight, I needed more projectors for my teachers.” Once the teachers understood how important it was to manage the mechanical, they came up with all kinds of ways of solving problems. It was the first time the staff had worked together on their own to solve a systemwide problem.

Diane reflects,

What I did not realize until later is that it also gave me a tool to manage the emotional outbursts about the district office. I realized that these outbursts were often at the lowest stage of innovation and that I could use this model to frame a conversation by asking, “What is it about this district office that creates such an emotional response?” Being new to the district, I learned more from my teachers about the district history and also that they were hanging onto now-ancient memories. Most of the key players who created the angst were long gone. Just talking through the issues changed the dynamic; at future staff meetings, these outbursts disappeared.