7 SCARF–Open to Diverse Viewpoints

Urban Luck Design, urbanluckdesign.com

Strive not to be a success, but rather to be of value.

—Albert Einstein

So far, for the conversations introduced in this book, it is assumed that participants are open and willing to coauthor a common future. As we have mentioned, this requires attention to building trusting relationships. When the stakes are low and of no threat, open-ended conversations appear easy; however, when the stakes are high or the work at hand carries emotional baggage, these open-ended conversations can be frustrated by responses from just one group member.

A friend tells the story about a forty-five-minute productive conversation about setting goals using a variation of the planning and reflection conversation (Chapter 6). Suddenly, one teacher raised his voice and in an angry tone said, “I am sick and tired of this. We have been down this path before; we are just wasting our time talking about how we are going to do this.” The group stopped cold and turned to the principal. While it wasn’t stated, they were silently asking, “What now, Boss?” Fortunately, this principal could turn to Humble Inquiry. He responded, “So this is not working for you today. What is on your mind?”

Through a few gentle questions, the principal uncovered the real issue, which was time. The staff had been discussing a complicated implementation plan that would require teachers to dedicate time to collaboration after school; this teacher was just getting custody of his children and did not want to commit after-school time. His real issue was about autonomy; he needed to be able to do what he had always done to stay efficient and preserve time for his family. His personal motivations were in conflict with the group’s. While Humble Inquiry uncovered the motivation, the SCARF model can be invaluable in helping groups better understand each other’s unstated motivations.

The SCARF Model

Through coaching and work with groups, David Rock (2010) has identified personal motivations—status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness, and fairness—which he calls SCARF. Using results of brain research, Rock described how these five domains activate emotional response systems in the brain—either the primary reward or primary threat system. These two brain circuits reinforce with rewards (positive) or with protective behaviors (negative). In the chapter’s introductory example, the negative response was provoked by the threat to this teacher’s need for autonomy—control over his non–classroom time.

Interestingly, at the sample meeting there was also a grade-level partner who loved clarity and was getting profound satisfaction from the certainty of a plan, thereby activating her primary reward system—certainty. Initially, she was frustrated, as were others, by the teacher’s outburst. However, when she and others learned more about his motivation through the Humble Inquiry process, the threat was reduced. When threat is reduced, groups demonstrate understanding and empathy and work to create possibilities that both acknowledge and honor others’ needs.

Much to everyone’s surprise, the staff found an amazing solution—this example demonstrates how the underlying motivations of SCARF can both add to and detract from a conversation. It turned out that a small group of teachers wanted to be acknowledged (status) and were willing to take the lead and make sure the after-school collaborations were on-target and focused. It just so happened that the woman who loved certainty was willing to work on implementation and then copartner with her colleague to help him focus on just the essentials. The staff agreed that for the first semester, while he was becoming reacquainted with his own children, he would not have to attend any of the after-school collaborations. They all agreed that this was a fair compromise. Our friend the principal reflects,

The funny thing was that teacher missed the first collaboration, but once he knew the staff would support him, he did not miss any of the other collaborations. It was a win–win, and I am so glad I could find empathy for him. In the old days, I would have been angry that he had ruined my meeting.

When groups learn to work with these five social domains, they find solutions to group dilemmas that are elegant and sustaining.

This example demonstrates how expanding our conversational repertoire can be particularly useful, especially when emotional responses have the potential to break down communications. The paradox of emotional responses here was that just when one group member got what she wanted (certainty), another lost what he most needed (autonomy). When these emotional reward/threat systems kick in, the behaviors become self-protective (stress response), and if groups are not mindful, the focus on common outcomes can be lost in the power struggle over competing needs. This is often described as a vicious cycle, which is a habitual, nonproductive way of communicating. Variations of the vicious cycle are evidenced in most dysfunctional communication.

S–Status, C–Certainty, A–Autonomy, R–Relatedness, F–Fairness

Each one of the SCARF motivations influences behaviors in slightly different ways and is likely best perceived as an answer to these two questions: How do individuals respond in the face of threat? What motivates individuals to make a particular response?

Status relates to a person’s sense of worth based on experience, knowledge, specific skills, or life experiences. When group members don’t feel validated or noticed, they seek status as a way of triggering the reward circuit. They are often called braggarts because even in everyday conversations they do not want to be perceived as any less valued than others. To reduce the threat and increase the reward value of this motivation, groups must find ways to give more credit to each other for the learning that is taking place. School culture that values diverse input and seeks all voices allows group members to be recognized in the course of the conversation, thereby reducing the need for status seekers to assert their status through bragging.

Certainty provides a sense of security by allowing the person to operate in familiar and more certain circumstances. Closely associated with certainty is a desire to anticipate the future. On the upside of this behavior is the drive for clarity and perseverance in seeking to understand. On the downside is the need to control and to operate from fixed views. To reduce threat and increase reward, groups need to work toward clarity and as much certainty as possible. Process structures, such as these conversations, that remain constant also help people feel a sense of predictability. When cultures have established routines for working through differences of opinion, group members learn to trust that certain processes contribute to a sense of direction and certainty. When groups have conversational processes in place, they are more willing and able to deal with the ambiguity of not knowing. Trusting that any conversation will find a logical ending point if the participants are patient is an important thing to learn.

Autonomy creates a need for control. Directives and other efforts to control behavior are often met with resistance. Opening up choice to give some autonomy provides options and gives the responsibility for deciding back to those who will need to act on the decision. This is a powerful motivator and activates the reward circuit. It is important to note that autonomy does not mean total control, but rather some aspect of control. For this reason, boundaries (rather than strict rules) allow for more choices. For example, in our sample the teacher wanted to control his time, while others wanted to maintain an investment in curriculum designs. By setting parameters, the group found boundaries that worked for all.

Relatedness builds mutual trust and encourages work toward common ends. A higher sense of relatedness influences the production of oxytocin in the brain and creates the positive emotions of the reward. Building relationships becomes motivating and can be the social glue that holds organizations together; yet these alliances can also lead to dysfunction. When group members form alliances that exclude others, they create “in” and “out” groups. For the “in” group, the bond of relationship is powerful; for the “out” group, these shifting alliances can create distrust and resentment. To reduce threat and increase reward, groups need to expect to cross relationship boundaries as part of the conversational design. Opportunities for short, pithy small-group conversations provide these opportunities and then become counterpoints to the larger discussions. One quick way to manage this is to build in reflection time at set intervals. When it is time to take a reflection break, group members are instructed to find someone they do not usually talk to, someone from another department or grade, or allow those who have been in a school fewer than five years to pick a partner that has been there more than five years.

Fairness communicates a sense of balance and encourages us to consider equity. In business, issues of fairness often arise around payment and reward structures such as bonuses. In schools, where pay is based on job function or time on the job, the perceived “investment of effort or time on the job” can be seen as a violation of fairness. When one person works long hours and the other skips out early, the threat response can kick in and get in the way of productive group work. Another fairness issue is the feeling that decisions are not fair; so more transparency, especially by describing why or how a decision was made, can lead to better understanding. Bill’s Minnesota friends often noted with humor when something wasn’t fair—they responded with the aphorism “Fair happens the ten days before Labor Day.” By this, they meant “Yes, life isn’t fair, so get over it.” As with most things, fair is in the eye and emotion of the beholder.

By now, it should be obvious that these five different motivations can easily promote bonding with a few and conflict with others. When a few strong people create alliances, especially if they include an appointed leader, they can make others feel decisions are not fair or that decisions are railroaded through. This can trigger any of the SCARF responses, with some experiencing reward and others perceiving negative impacts. These can be particularly toxic environments.

For those who work in organizations with cliques, the key is to find ways to open conversational doors across the relationship boundaries. Picking topics that are more neutral—less important to the group members, but still worthy of time and attention—is one way to open the door. When a friend of ours, Kim Harper, first became a principal, she found a common purpose by working on uniform spelling expectations for the school. It turns out that most teachers welcomed suggestions, as they had not given their own practices much thought and hence were not much invested in the outcome. In reflection, she describes these conversations as pivotal in building the collaborative culture, which became a hallmark for this school. She states, “The feeling we had of having found common ground was an important first step toward my long-term goal of building collaborative cultures.”

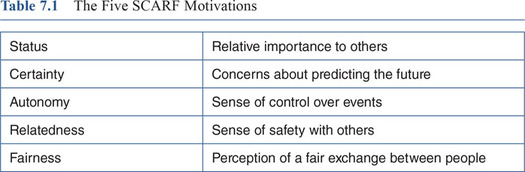

To summarize, knowing about how SCARF needs drive behaviors allows the coach or group to stay more tuned in and be able to slow down to listen and engage in inquiry so as to understand these unstated motivations. Listening for the motivations opens up understanding and makes what seemed odd or offensive understandable. When humans understand the motivations behind behaviors, they are willing to let go and engage to remove points of conflict. Giving the teacher in the sample story control removed the protective behaviors and resulted in positive, productive team members and a team solution. To aid in recall, we offer a short review of the five SCARF motivations in Table 7.1.

Understanding how differences either limit or expand our capacity to learn together as a group is an important developmental threshold that changes cultures from ones of complaint to ones of solution. Just one person can change a vicious cycle into a virtuous cycle by deciding to act as a catalyst—by paying attention and actively listening and inquiring about underlying motivations. When a few serve as catalysts, others follow along and begin to generate solutions well beyond the normal expectation. This kind of work stimulates the reward system in the brain and creates virtuous cycles—the belief that a beneficial path can be found. This feeling of competence creates a feeling of renewal and the desire to have more conversations that are similar.

Once again we reinforce the theme of this book: When the coach or facilitator is seeking positive change, instead of dictating next steps the job becomes one of creating productive conversations that allow the group, and individuals within the group, to explore and produce the effective solutions. These solutions are both win–win and value added. For example, once this teacher had autonomy and trusted the group, he participated without complaint. It may seem small, but for this teacher, having choices was important. The larger, value-added benefit was that the group had a firsthand experience in how diversity enriches group work. Issues of conflict and diversity will become stronger themes as we move to the right side of the conversation arc.

Interaction Models Versus Diagnosis

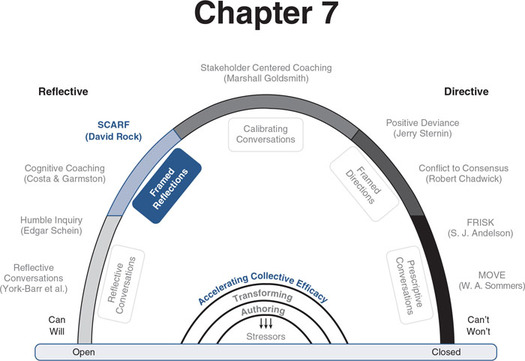

Rock (2010) describes SCARF as an interaction model—one that minimizes threat and maximizes rewards in relation to the five identified domains. In the example, the staff did not have to label the motivation to achieve success. It turned out Humble Inquiry led to the unexpected solution. Understanding the SCARF model, however, helps peers begin to understand and appreciate diverse responses. It is important to understand at this juncture that as long as individuals are invited to explore these motivations for themselves and reflect on their work based on what they are coming to comprehend, the conversation lives on the left side of the arc. If, however, even one person imposes a diagnosis on another—makes a judgment about another—the conversation moves to the right side of the arc. When labels are applied, without realizing it the speaker directs the other’s thinking in a specific way and runs the risk of shutting down creative thought. Put yourself in our teacher’s shoes and consider how you would have responded if the principal or another teacher had said any of these things in response to the teacher’s outburst:

- “Your comment is getting in the way of our productive work. We’ll finish in 15 minutes, and then you and I can talk in my office.”

- “I just went to a workshop, and I think the SCARF model would help you better deal with your need for autonomy.” (Implied here is “I have been secretly diagnosing your behaviors.”)

- “When you report that this ‘wastes time,’ I think that you are seeking autonomy. What is it that you want?”

By now, the reader can discern that none of these responses are helpful. Even the last response that begins an inquiry misses the mark. It may seem strange, but emotional responses do not come with rationale, so asking the person what he or she wants can be problematic. The heart of the matter is that when someone makes an emotional response, no amount of reasoning or rational thought will bring a solution. Emotions must be understood, accepted, and validated through the emotional mind. The simple paraphrase “So you think this meeting is wasting your time” paired with the question “What is on your mind?” communicated an acceptance of the emotion and validated that this response was important enough to take time to understand it.

The irony of this entire story is that this curmudgeon’s outburst ended up being a gift to the group. By listening and inquiring, they found elegant ways to meet his needs but also used their own talents to support the entire group. The dissenting view ended up putting creative tension into the conversation and produced a value-added response.

SCARF Reflections—Checking In With Our Emotional Brains

No matter what the topic, it is often helpful to take a reflective break to check in with group members as a way to open up the conversation and give individuals a chance to respond to concerns. One way to use this model is to teach groups to do a SCARF check-in about two-thirds of the way into the conversation. By this, we mean taking a short reflection break to ask, “What are we thinking or feeling?” At that point, the teacher described earlier would likely have voiced his concern, but it would not have been so emotionally loaded. He might have said, “Planning all these after-school meetings is problematic for me.” The teacher who loved certainty might have said, “For the first time in a long time, we are all planning to do something together. This excites me!”

These check-ins should be quick and efficient, with group members rotating between giving opinions and serving as catalysts, listening and reflecting on what they are learning about differences. When initially starting a SCARF reflection, it can be important to ask all group members to respond in some way, even it is just to say they are “neutral.” Once the group learns that this is a safe space for voicing different options, only those who are experiencing an emotional response—positive or negative—need to speak up. Once participants have stated problems and know they have been understood, they are more likely to negotiate to get what they need. This is the nexus of using creative tensions to come up with elegant solutions (see Box 7.1 for more details).

When these check-ins become the norm, they often do not take more than five minutes. Sometimes all someone wants is to be heard. Diane learned a valuable lesson about how even an overwhelmingly positive meeting can have silent dissenters. Indeed, the more positive a group is, the more isolated and alone dissenters will feel. At the end of a positive school site council meeting, one member quietly said, “I did not feel there was any space for disagreement today. Everyone was so excited that I did not feel comfortable voicing a concern.” Because this group had worked hard to develop norms that supported open, honest conversations, they were stopped dead in their tracks. The member went on to explain that she realized she has some issues of fairness and that her opinion probably would not change the ultimate consensus, but it would have been validating had she had a chance to speak her mind. The lesson here is that dissenters can provide valuable input and should not be ignored. We will return to this when we move to the right side of the conversation arc.

Box 7.1 SCARF Reflection—A Check-In With the Emotional Self to Open Up Diversity in Thought

“At this point in the conversation, it is time to check in with the group’s emotional core.”

This is usually at the point when the group (1) becomes overexcited, (2) becomes overheated, or (3) begins to lull.

Prompt: “Take a moment and think about this question: As an individual, what are you gaining or losing with this change?”

- ■ Status—Gaining or losing expertise

- ■ Certainty—Gaining clarity or experiencing more confusion

- ■ Autonomy—Developing or losing control

- ■ Relatedness—Feeling more connected or more isolated

- ■ Fairness—Gaining or losing a benefit or investment of time

Directions:

- ■ Take a moment to reflect silently, and then turn to a partner and share insights gained from this reflection.

- ■ Invite the group to reflect about what they are learning that builds an understanding of strengths and differences.

Inquiry Opens Up Understanding

We first started using the SCARF model as a way to diagnose needs and then tried to match those needs with opportunities for contributions from the group. We now see the SCARF acronym as another way to frame inquiries. Furthermore, when groups learn to embed this type of reflection into their collaborative work, staff members become more comfortable stating needs and are able to maintain a positive contribution. Not taking these five values into account may cause missed opportunities for accelerated reflection. Indeed, Rock (2010) and those of us who have applied his model have advocated that leaders can enhance teamwork and build positive school cultures by focusing on the positive reward of each of these motivations as follows:

- ■ Increasing perception of status with positive feedback

- ■ Enhancing levels of certainty by creating boundaries that are the same for everyone

- ■ Validating autonomy by creating options that allow for some choice

- ■ Improving relatedness through open communication and coaching

- ■ Verifying fairness by asking for perceptions about assumptions

These are worthy goals, yet we advocate that the solution is not in one enlightened leader but in how groups come to embody these beliefs; this only happens when groups create their own culture based on these reward systems. The old adage “You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make him drink” is true here. A leader can work hard to create a positive culture that reinforces the positive, but if the participants are not aware and hence not ready for these interventions, they will be of little avail. When leaders take responsibility for creating the culture, by diagnosing and then creating opportunities, they end up working harder than everyone else. And, as Schein reminds us, they run the risk of offering suggestions that are neither wanted or helpful. Instead, when leaders set parameters as identified by the conversations in this book, the participants create their own best futures.

As teams find coherence and alignment in their thinking, they began to develop their own knowledge legacies and take responsibility for helping newcomers understand and join the culture. This is a powerful antidote to teacher burnout that drives many from the profession. The lesson is this: When we want to drink, we drink in and nourish not just our thirst; we replenish our souls, and when this happens, the experience is renewal and the activation of a powerful reward circuit.

Learning About Diversity

Learning about SCARF can open up understanding and help groups capitalize on learning about diverse skills, but it is important to note that any model of behavior that is descriptive about different viewpoints can be applied to open up understanding. It is not uncommon for facilitators to use style inventories such as Myers-Briggs (www.myersbriggs.org) or Gregorc (gregorc.com) to help groups understand personality differences.

In the early 1990s, the Federal Mediation Board introduced the Working Styles Assessment to negotiators from the Davis Joint Unified School District to help them better understand how they had almost come to a strike (see (http://partnerships.hivechicago.org/content/uploads/2016/06/01_Working-Styles-Assessment.pdf). In this case, the groups took a quick self-assessment to determine personal working style strengths: analytical, driver, amiable, or expressive. (Note: This model was originally developed by Merrill and Reid [1981]). Once the different groups were established, they took time to explore how these different styles contributed to the misunderstandings. This same process could be used with the SCARF model. The important point is that the participants were taught the model as a way for them to self-evaluate their own behaviors. No one from the outside imposed his or her assumptions about how this district almost came to a strike.

A much more complicated and nuanced way of looking at how values and beliefs influence behaviors can be found in the work of Stan Slap (2010) and his book Bury My Heart in Conference Room B. Slap suggests asking what is the person’s most important value. Go to Slap’s website (www.slapcompany.com) to find the list of fifty values he identified, and for the full directions to a group activity, go to https://tantor-site-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/bonus-content/1755_BuryMyHeart/1755_BuryMyHeart_PDF_1.pdf. Some of the questions Slap suggests are as follows:

- ■ If you had to pick one of these values—the one most meaningful for you—which one would it be?

- ■ How did you get that value? (This usually elicits a story from life experiences.)

- ■ Share your thinking and feelings with a partner.

- ■ What are we learning about ourselves?

Bill regularly uses a shortened version of this activity with groups. He projects the fifty values at the front of the room and then takes the group through the questions Slap suggests. When we worked with Stan Slap, we found his process to be provocative and reflective. For those wanting more skill in this area, we refer you to Slap’s books listed in the reference list.

Value-Added Conversations

What is interesting to note about models that describe sets of behaviors, as the SCARF model does, the group need open only one door to begin to understand. Through these types of discussions, group members gain insights into others’ motivations and can compare and contrast these to their own motivations. For the chapter example, when the need for autonomy was understood, each person was able to respond from his or her own personal reward system. The grade-level partner who sought certainty stepped in and found ways to use her clarity to help focus on just what was important. Other members of the staff agreed that it was fair to opt the teacher out of after-school meetings for the time he needed to reestablish his after-school family time. A few gained status by agreeing to do extra organization work. Through this conversation, they all began to feel more related and empathic. In other words, the same behaviors that protect also lead to productive pathways. The trick is to get school culture to shift and seek out the diverse ways groups can support each other in the quest to create better learning for all, both students and adults. When groups learn to embrace their diversity as an opportunity to find a creative edge, they cross an important threshold and begin to seek out diverse viewpoints. This attention to diverse viewpoints builds knowledge legacies.

Reflection

A Place to Pause

iStock.com/BlackJack3D

How to Build Knowledge Legacies

- ■ Create virtuous cycles of learning.

- ■ Become a catalyst for knowledge expansion.

- ■ Listen for understanding and amplify ideas with paraphrase.

- ■ Use Humble Inquiry.

- ■ Listen and inquire about underlying motivations.

- ■ Verify assumptions by asking.

- ■ Ask others to respond, based on this new information.

Expanding the Knowledge That Supports SCARF Conversations

Kim and Marbogne (2003) published an article in the Harvard Business Review on “fairness.” We reinterpret it here as another way to think about how SCARF motivations are embedded within context. Thinking about fairness in relation to the other four motivators can add value to check-ins during or at the end of a meeting by asking from the following SCARF categories. By confirming the “SCAR” part of SCARF, fairness is more assured.

- ■ Engagement (builds relatedness)—Have group members been heard? If people cannot tell their story, the process does not seem fair.

- ■ Explanation (builds autonomy)—What is the thinking behind the decision? By understanding the thinking behind a decision, groups can more effectively find options and establish boundaries rather than rules for behavior.

- ■ Expectation (clarity creates more certainty)—Have processes and purposes been made clear? Transparency is key, especially as groups decide on the process tools to use to shape a particular conversation.

We add a final expectation:

- ■ Expectation of appreciation (builds status)—Have group members been recognized for their contributions? A genuine thank-you for something specific is always appreciated.

Together, these four ways of thinking about fairness foster successful conversations and, as a result, give the entire group status. When added to the other practices learned in this book, groups build cooperative capabilities—a belief in their own capability to take appropriate actions. To review, collective efficacy defines a group as one that has the skills needed to take collective actions and reflect on these actions to further improve their skills. Collective efficacy rewards with status; those schools note that they have learned to do something that was once just a dream.

Having multiple options for setting contexts for professional conversations generates positive results. What we think can divide us. What we feel unites us. Everyone knows what being mad, sad, glad, scared, or rejected means. Bring people together, and when the work is productive it creates better relationships and better responses. There is wisdom in crowds.

Scenario 1

Bill points out that when using SCARF as a diagnostic tool we can both hit and miss the mark. A teacher he worked with was innovative, used data as feedback about his own teaching, employed technology to expand his teaching repertoire, and was very popular with students and parents. But because of his strong personality, he was not looked upon kindly by some of the other staff members. Some thought he was a know-it-all. Thinking that elevating his status would help him connect with staff, Bill and his leadership team tried a few things, like inviting him to serve on the leadership team, putting him in charge of the school goal to raise test scores, and having him co-chair the team meetings. At the end of the year, he quit all of those positions because he did not feel colleagues respected him.

It turns out that, for this teacher, being connected to a small group of teachers and having regular visits from Bill was enough to satisfy his status issues. Furthermore, because he was such a strong teacher, Bill learned more about effective teaching, and from time to time, he would ask him to coach others. He seemed to really value the time Bill spent talking about his teaching, when he asked his opinion, or when he asked him to work one-on-one with another teacher. Honoring his status and having fruitful conversations kept his positive affect and seemed to reduce his need for public status comments in staff meetings.

Scenario 2

Years ago, Diane was required to give a tough message to her staff, with little time for planning or deliberation. On a Tuesday night, the superintendent told Diane that he was recommending to the school board on Thursday that they consider reconfiguring her school from an intermediate (Grades 4–6) building to an elementary (K–6) grade pattern. Housing needs of a growing dual immersion program drove his decision, and Diane’s school was picked because with three grade levels it was one of the smaller schools in the district. This meant that her entire school would be disrupted and that some teachers would need to transfer.

Initially, Diane was distraught; she had worked so hard to build a culture of inquiry and an open, transparent way of working together. How could she help her teachers understand and be ready to meet with the superintendent the next afternoon? After sleeping on it, she realized that she needed to appeal to the staff’s sense of fairness as a way of preparing them to meet with the superintendent that day after school.

Diane addressed fairness outright by telling the teachers how she had learned of his recommendation the night before and how she had felt that it was “unfair.” She said, “Arguing with him from this position will not help. Instead, I am going to offer another path.” Following an inquiry path articulated by Stephen Covey (1989), she asked her staff to “seek first to understand, and then to be understood.” (Note: This is also Humble Inquiry.)

In order to do this, she reminded the staff to use the tool they used in staff meetings to Balance Inquiry With Advocacy (see p. 208). Second, she reminded them that fairness was about perceptions and that it would be helpful for them to consider the decision through lenses of Concerns-Based Adoption (2015), using a simplified modification. Diane explained that their issues would be personal and mechanical, the initial stages of concern, while the superintendent would focus on the highest level—how this decision would benefit the district (see http://www.sedl.org/cbam/stages_of_concern.html). Once again, she had a graphic they had used in a previous staff meeting (see p. 209).

The most amazing result occurred. Instead of arguing with the superintendent, the teachers began an elegant dance of listening and inquiring. Instead of advocacy, they actually coached the superintendent and helped him uncover his biases. What was even more interesting was that the sister school (K–3 configuration) joined the meeting and, after listening to the lead set by Diane’s teachers, began to inquire in the same way. Neither principal said a word; together, they sat and listened to one of the most elegant group coaching sessions either had ever seen. Afterward, the other principal said, “I don’t know what happened here, but I was so impressed by our teachers; they are truly amazing in their ability to listen and respectfully respond.” (Note: Ultimately, this school was not reconfigured immediately, but it was reconfigured three years later. No doubt everyone in the room probably realized that eventually this action would need to happen.)

While this example did not address the entire SCARF model in its entirety, it does remind that just one of these motivations—fairness—can be put to work to look at both the negative and positive intentions of a decision. This also reinforces our belief that other participants can easily adopt models of linguistic excellence. This is an example of how the modeling of accountable listening—paraphrasing, pausing, and inquiring—had a profound effect on the entire meeting.

The Final Note—Using SCARF to Think About Teaching

Bill has used the SCARF model as a way for teachers to reflect on their practices and also to highlight excellence. Any of these question frames would be worthy of a Reflection Conversation as described in Chapter 4.

Status

- ■ What are some of the methods you use to get these results, and how would they contribute to the school knowledge base?

- ■ This staff is knowledgeable and experienced. What strategies are you using that would benefit the entire school?

Certainty

- ■ Knowing that the world keeps changing, what are the foundational instructional strategies that we believe ought to be constant?

- ■ As you think about your experience here, what are some things you believe should be changed? How could we change those things?

Autonomy

- ■ As veteran teachers, what are you continuing to focus on to increase your impact with students?

- ■ How can we balance what works now with finding out what else works for these kids?

Relatedness

- ■ Our school continues to be more and more diverse. How are we building relationships with students that come from different backgrounds?

- ■ Student performance has gone up. What has each of you done that helped students know we care about their learning?

Fairness

- ■ Knowing kids see fairness differently, how do you sustain the goals of learning while accommodating for such diverse needs?

- ■ What are the things that don’t change in your classroom for all students? What are things that are negotiable, depending upon the needs of the student? How do these relate to those of your peers?