6 Cognitive Coaching—Lingering in Conversations to Learn

Urban Luck Design, urbanluckdesign.com

Fight the temptation to “know” and instead work to become curious about what the group “knows.”

—Micah Jacobson, Open to Outcome, 2004

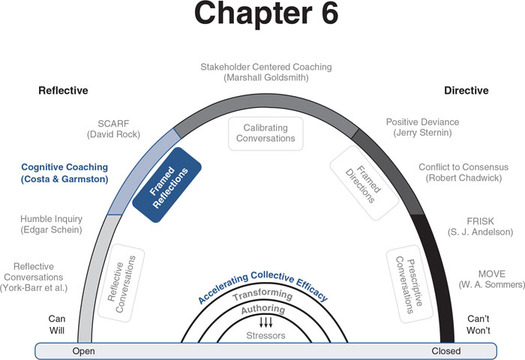

Over thirty years ago during the formative years of Cognitive Coaching, we were invited, along with others, to join Art Costa and Bob Garmston to form a collective partnership to support the development of Cognitive Coaching in schools. While Cognitive Coaching was originally conceived of as a one-on-one coaching cycle, the emphasis was always on communication skills, such as building trust, listening through the paraphrase, and building a culture of inquiry. Early in our collaboration, those of us working in schools observed how powerful these communication skills were for shifting school cultures from scarcity and limitation to abundance and reflection. This work challenged us to not only perfect communication strategies but to also build communities for reflection. We talked often about how to grow schools as “homes for the mind”—how to build cultures of inquiry.

As conceived of by its founders, Cognitive Coaching was about changing thinking, not about changing behaviors. This meant that rather than giving technical advice, often a common aspect of coaching, we taught others how to inquire into the thinking processes. In this respect, this work is similar to Edgar Schein’s. The goals are not to fix another person, but rather to build trust to ensure learning and to encourage autonomy and self-reflection. This requires that the coach or facilitator set aside personal agendas in order to seek possibilities generated by the others. This means that the coach needs to stay open to outcome. This ability to set aside personal solutions and to become curious about possible outcomes allows agendas to unfold. This ability to take a neutral stance and be of service to another or a group is central to our work as cognitive coaches and the thesis of this book. We are not advocating fixing others, but rather opening up pathways for others to find their own best solution. We seek schools where this open access to human thinking changes school culture.

Dedicated to Process—Planning and Reflection Conversations

Process matters and determines the outcome of conversations. Each of the conversations in this book describes how changes in process can tip the outcome ever so slightly and yet make huge differences. As cognitive coaches, we teach communication strategies for trust building and how to build inquiry cycles designed to open up deep thinking about teaching and learning. The job of the coach is to listen, paraphrase, and ask questions designed to explore intentions and expectations, as well as actions. We learned to linger in a conversation until we can discern a shift in thinking. These shifts, always accompanied by a change in posture or prosody, give powerful clues to the coach that indeed this “thinking out loud in public” brings new insights. We labeled this moment the cognitive shift.

The core conversations of Cognitive Coaching—planning and reflecting conversations—focus specifically on goal setting and attainment. These types of conversations are important for any type of performance art, such as teaching, facilitating meetings, or leadership actions. Planning and reflection conversations extend the reflection for–in–on practice to deeper levels. These conversations raise consciousness and invite introspection and work equally well with one-on-one coaching for group planning and evaluating.

Most teachers go through a process of planning for and reflecting on instruction; however, these practices vary widely and depend upon the teachers and their own diligence in lesson design and evaluation. No teacher can ever possibly reflect on everything he or she might do in a day, so by definition, this process is selective. As teachers become more skilled, some teaching behaviors become habitual and routinized, and reflection tends to decrease. For this reason, most teachers find the coaching cycle a refreshing reminder about the importance of this type of introspection, which might have been forgotten had they not been coached. We have found that the simple planning and reflection questions embed in the teachers’ thinking and become habitual processes for thinking after only a few sessions. These questions become a resource that the enlightened professional can pull from at any time to reflect on practice.

We have worked in the world of coaching for most of our professional careers and, as a result, are discriminating about how to describe the various coaching models. Our obvious bias is to work toward thoughtful reflections about practice.

While technical coaching can have its place in assuring that a particular way of teaching is being implemented, we find that for most teaching acts, teachers are guided by far more interesting and complex questions about their practices. As mentioned earlier, the simple planning and reflecting conversations are invaluable for quick interventions; however, we find the real work occurs during the longer conversations that we have when we take the time to probe the other’s deepest thoughts. There are no shortcuts to thoughtful conversations.

Planning Conversation

As stated in Chapter 4, the ethic of inquiry requires that the listener slow down and ask questions to learn more from the other person or to probe from a deep well of curiosity about the topic of focus. A major portion of Cognitive Coaching training focuses on building this ethic of inquiry—that commitment to ask questions that neither person has a preconceived answer for.

In Box 6.1, the thinking prompts of a planning conversation are outlined. For the purposes of this book, we have used slightly different words than found in the training materials. This is partly for brevity and partly to make the questions applicable to both individuals and groups. Take moment to review the key inquiries. Remember the goal is not to get done, but to linger long enough to allow the other person to delve more deeply into his or her own thinking. The linguistic skills of pausing, paraphrasing, and probing further enhance these conversations and are reviewed in more depth later in the chapter. The ethic of inquiry is assumed in that these questions are asked in the spirit of learning more about outcomes and going deeper, not just covering the territory.

Box 6.1 Planning Conversation—Organized Around Four Key Inquiries

- ■ What goals/outcomes have you set? (Goal)

- ■ What steps will you take to accomplish these goals? (Plan)

- ■ How will you measure your success? (Criteria)

- ■ What data might you collect? (Data)

Teachers report that these questions have helped them think specifically about what they want the students to learn and how to begin to collect data as part of the teaching process. It turns out that these questions also require that a teacher step out from behind the overly scripted teacher’s manuals, which are part and parcel of the high-stakes testing environment. These simple questions help the teachers pull what is important from these manuals, while encouraging them to include their own expertise. As one teacher put it, “During the first year of our language arts adoption, I was overwhelmed with all the materials. I found that your questions helped me narrow down and focus on what I really wanted from my students.”

It turns out that planning conferences have an additional benefit of increasing awareness during teaching by increasing consciousness. The planning conference serves as a mental rehearsal for the lesson, thereby increasing preparedness. Teachers often report that the conversation before the lesson made them much more attuned and observant during the lesson itself—as defined in Chapter 4 as reflection-in-action.

Planning and Reflection Are a Cycle

In the 1980s when the lines between supervision and coaching were often blurred, some decided that a planning conversation, formerly referred to as the preconference, was not necessary. It was during these years that Madeline Hunter first started to quantify elements of effective instruction and many supervisors saw their job as inspection: Was the teacher using the five elements of a lesson plan or not? When the supervisor considered the work that of inspection, he or she considered preconferences a waste of time. The problem with this assumption was that it limited the conversation to technical discussions about how the teacher did or did not meet the expectations. The irony of this is when a teacher was competent, the supervisor often skipped the postconference as well. It was not uncommon to find a note in the mailbox that said, “Great lesson. All five elements of instruction were present. No need for a postconference.”

This digression into history points to the heart of the issue still with us today. Reflective practices require conversations. Reflective practices happen when school cultures establish them as a norm for how they do their work. How refreshing it would have been all those years ago if the principal had said, “You have the elements of instruction down, so what else are you thinking about when you plan for instruction?” In the end, teachers in California turned to unions to protect them against the tyranny of such a narrow view of instruction, and in some districts, the Madeline Hunter model was specifically written out of evaluation clauses in contracts. When one person holds a tool that she or he perceives as “the solution,” thinking shuts down and defensive behaviors often kick in.

To make the point, in Cognitive Coaching training, we’d tell the story of how one expert marksman gained his reputation. Instead of worrying about hitting the bullseye, he’d shoot and then draw the bullseye, creating a perfect shot every time. He never needed to become a better marksman. While the coach cannot quite hit every bullseye, deciding after the fact what to focus on has the same impact: It shuts down learning.

So we cannot stress enough that these two conversations—planning and reflecting—belong together, not apart. As previously mentioned, reflection can start at any point in the process; however, when these conversations bookend teaching, both conversations are essential. Without one, the other will lose its potency as a reflective tool.

The Reflection Conversation

While the planning conversation is focused on goal setting, the reflective conversation is organized around how humans compare and contrast to evaluate the efficacy of actions. Once again for brevity, the terms here are slightly different than those found in the manual, and the ethic of inquiry is assumed.

Bill found that the simple question frames in Box 6.2 were invaluable to him while working as a high school principal. While out and about campus, it was not uncommon to have to conduct business on the fly. Teachers would often reach out to him for help, and rather than offering his own solutions, he’d often ask them about outcomes and strategies. Instead of asking about lessons, he would ask, “So what happened that raised your concerns?” and then would follow up with “Based on what you observed, what might you try?” While it was not possible to linger while walking the campus, these questions would bring solutions. Even in a three-minute conversation, Bill states, “Teachers would regularly find their own solutions.”

Box 6.2 Reflection Conference—Organized to Elicit Reflective Thought

- ■ How did the lesson turn out? (Comparing intentions to impact)

- ■ What teaching actions supported your successes? (Causal actions)

- ■ Based on what you observed, what might you try? (Data focus)

or

- ■ What got in the way of your success, and what would you change? (Causal actions)

- ■ What teaching practices would you change and why? (Evaluation)

- ■ How might we collect better data to inform your teaching? (Data focus)

- ■ How would you apply what you are learning to future lessons? (Applications)

Lingering in the Conversation

One of the most significant differences between Cognitive Coaching and other models of coaching is the focus on deep thought. Early in our work, we learned to use inquiry as a way to help others solve problems for themselves. This focus on problem resolution expanded Cognitive Coaching repertoires from a strictly supervisory focus to a model for adaptive change. Cognitive Coaching was our first experience of the power of deep, reflective conversations to change the way we think and also our practices. Teaching, being full of dilemmas, is well suited for this unique, adaptive form of reflection. When teachers come together to think deeply about practices, based on personal understandings and what is learned from others, they report renewal.

A by-product of the listening skills that are taught as part of the Cognitive Coaching process is that they slow down the conversation and open up space for deeper thinking. Important to the coaching process is pausing, paraphrasing, and probing. We find that when a coach uses paraphrasing to communicate understanding, it encourages expanded thought. Often, the response is, “Yes, and another thing I am thinking about is . . .”

Likewise, the act of paraphrasing and inquiry require that both parties slow down and respond in thoughtful ways. When questions are asked from a point of curiosity, they are engaging to both parties. While these conversations can be short, the real value comes when the teachers decide to talk in depth about what they are coming to understand. The value is both the frame and the ability to linger. This learning is so important for the success of all conversations that we explicate it in more detail here and call it accountable listening.

Accountable Listening Extends and Expands Reflection

Accountably requires acting with congruence on intentions—in other words, to match intentions to actions. If we intend to listen, we need to demonstrate that intention.

Accountable listening employs three practices that make listening overt, authentic, and accountable, as summarized in Box 6.3. Because these behaviors are overt, they are also observable; hence, there is never any question about the commitment to listening. Indeed, the commitment to listen is necessary for any of the conversations in this book to be effective. Listening is the true catalyst for all conversations, creating cultures that are authentic and leave personal identities intact.

Box 6.3 Accountable Listening Practices

- ■ Confirming paraphrase—Confirm the commitment to listen deeply by summarizing understandings.

- ■ Thoughtful pause—Confirm this commitment by taking time to think.

- ■ Ethic of inquiry—Confirm this commitment by inquiring for learning.

Confirming Paraphrase

The first commitment of accountable listening is to listen deeply; this is demonstrated by authentic paraphrases—a restatement of what the listener is coming to understand—sprinkled throughout the conversation. To emphasize, paraphrasing is not the parroting of words, but a statement of what the listener is coming to understand. In order to paraphrase, the listener pays deep attention to the message and often comes to understand nuances that are otherwise missed. Communicating that we understand is one of the most inexpensive and authentic gifts we can ever give another person.

Effective paraphrasing requires deep focus and is a summary of what has been understood in the listener’s own words. The paraphrase serves to validate that the listener understood the message. Paraphrases also allow time for clarification; when the message is not received as intended, the speaker corrects it. Paraphrases take us deeper into the conversation. When humans feel understood, they breathe more deeply, bringing more oxygen to the brain and opening up to deeper reflections. When humans hear their thinking reflected back to them, they feel validated and, as a result, will often add more information. By design, paraphrases elicit more contemplative speech. When paraphrasing is used with regularity, the speaker comes to expect this authentic response and appreciates the way it slows down the conversation by opening up space for thought.

Yet over our thirty-plus years as trainers, we have found some who resist or even refuse to paraphrase. The reasons are varied: it does not feel comfortable, why state what is obvious to me, it seems like overkill to me, and so forth. But when we ask the speakers how they received the paraphrase, the response is overwhelmingly positive—I felt supported, I felt listened to, and so on. Notice that all the reasons for not paraphrasing are about the listener, not the speaker. Time after time, these novice paraphrasers have missed the point—this is not about the listener, but about being of service to the speaker.

Reflection

A Place to Pause

iStock.com/BlackJack3D

- ■ How is accountable listening of service to both the speaker and the listener?

- ■ What is your own relationship with the paraphrase?

- ■ Based on your reflection about your own habits, what would you change?

- ■ How might using paraphrasing change the cadence of your conversations?

What is often not known about paraphrasing is that it is a powerful way to shift conceptual focus toward a more global or detailed way of thinking about something. It turns out that this form of summarizing also helps the listener organize thoughts. For example, when a teacher gave a particularly long paraphrase that detailed student responses, the coach summarized just a few examples and then added, “Cooperative behavior is an important value for you.” Adding this label was like turning on a lightbulb for the teacher, and she responded, “Yes, that is exactly what I value—cooperation.”

In another example, a teacher was confused by a behavior exhibited by a student. The coach summarized the confusion and then clarified, “So you assume that the behavior was purposeful?” In this case, the teacher thought out loud, “I am not sure about that; sometimes I do and sometimes I don’t, so I guess that is why my responses to this student are uneven.”

Thoughtful Pause

The second commitment to accountable listening is to take time for thoughtful pauses. By this, we mean slowing down the conversation, taking a deep breath, and thinking about what is being learned. This pause gives time for both listener and speaker to really think about the conversation. It gives the listener time to consider when a paraphrase is warranted or perhaps when a question would be more appropriate.

Pausing and paraphrasing go hand in hand. Initially, the listener needs the pause to think about what was heard; then the speaker needs to pause to think about answers. The pause is what gives speech its cadence and shape; it slows down breathing and signals respect for the other person’s thoughts. The pause allows group members to move in sync with one another by signaling turn taking or the need to stop and think.

The pause allows time for small reflections, a necessary ingredient in the continuous development of individual and organizational learning capacities. Any teacher who has used Mary Budd Rowe’s (1986) strategy of “wait time” knows how important the pause is to support thinking. Rowe found that most teachers do not provide time for students to think after asking a question and that pausing even for just thirty seconds improves student responses. For teaching, coaching, and facilitating, the pause allows for the listener and the speaker to check out each other’s response and communicates how to pace the conversation, by allowing time for thought and turn taking in conversations.

Ethic of Inquiry

This ethic of inquiry requires a deep commitment to be of service to the other and to ask authentic questions for which the listener is curious and has no preconceived answer. Questions, when asked from an attitude of curiosity, heighten thinking. Consider a question asked from an expert’s agenda: “Why didn’t you introduce the vocabulary in the beginning?” This question assumes a correct action and, as a consequence, the answer will be a justification, not an exploration. Consider this question asked out of curiosity: “I am wondering what you might do to assist students with the vocabulary to support your goals.” This question invites the other to think out loud about possible solutions.

This emphasis on “ethic” reminds us that inquiry is a moral principal—maintaining a respect for the learning of others. Questions deepen intellectual curiosity, and the most powerful questions often shift thinking and become transforming. Questions asked from an authentic point of reference model ethical ways of relating and, as a result, produce ethical behavior in others.

Accountable Listening Assists Groups in Managing Conflicts

Before moving on, we make one more important point. Just the few moves of accountable listening can solve just about any conflict, and it can be done with any group. We know, that might seem preposterous, but consider this example.

A school is just finishing up a presentation on an action research project, and two teachers get into an argument. As part of the study of student engagement in reading, the teacher had allowed small groups of sixth-grade students to select books that he had not reviewed; the librarian was incensed that he would be so lax. They began to argue loudly in front of the entire staff. The facilitator, skilled in the Chadwick model (Chapter 11), interrupted the diatribe and said, “We have a conflict here. Let us make sure we understand the viewpoints.” She divided the teachers into two groups and invited each group to work in pairs to summarize one side of the debate; half the teachers paraphrased the teacher and the other half the librarian. This took about four minutes. The facilitator then focused the group on two charts and alternated between putting up the viewpoints for each position. This took another four minutes. Turning to the two in conflict, she asked if anything was missing. They both responded no and were strangely calm; the conflict had evaporated in fewer than ten minutes, and the staff now had consensus on the problem. The facilitator then assigned the task of next steps to the leadership team. They went on with the planned agenda, knowing that follow-through would happen at a later date.

Conflicts invite accountable listening, and when used respectfully, accountable listening almost always reframes a conversation toward productivity. All the conversations in this book assume a commitment to accountable listening. We will delve more deeply into this theme in Chapter 11.

The Cognitive Shift

Over the years as coaches, we lingered in the conversations in order to provoke deep thought, and we noticed another phenomenon. When thinking deeply about an issue or problem, it is not uncommon to find a new understanding and a change in mind. The person being coached will often report a small, internal aha moment when her or his thinking shifts to something new or enlightening. For the coach, this change is observable. The person almost always shifts posture or makes an audible sound of approval, and facial features often show a change toward a look of surprise. These changes in body language can be missed, unless the coach learns how to observe and calibrate based on these behaviors. Cognitive shifts demonstrate the power of a thoughtful conversation, which goes deep and accesses our deepest unconscious resources. There is no rushing here. And not only do these conversations offer a chance for authoring, but they are also transforming.

Using the Dispositions of the States of Mind to Build Collective Efficacy

In the last two chapters, reflection was used as a general way to think on–in–for practice. In Cognitive Coaching, reflection is expanded to help reframe experience from limitations to positive outcomes. Applying the work of cognitive psychologists on reframing, Costa and Garmston (2015) identified five forward filters that shift thinking toward positive outcomes. Forward filters are dispositions that focus thought on solutions rather than concerns. In the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education Glossary (2017), the term professional disposition is defined as follows: “Professional attitudes, values, and beliefs demonstrated through both verbal and nonverbal behaviors as educators interact with students, families, colleagues, and communities. These positive behaviors support student learning and development.” We know of no other coaching model than Cognitive Coaching that so directly focuses on dispositions for thought and hence works to directly build teacher efficacy.

These five dispositions, which Cognitive Coaches call “States of Mind,” are efficacy, consciousness, flexibility, craftsmanship, and interdependence. In coaching and facilitating, these dispositions are used as a way to expand inquiry toward positive outcomes. Box 6.4 has examples of how these dispositional frames can anchor concepts, shape the inquiry, and foster collective efficacy.

These five mind states are gifts of thinking. They invite searching for a multiplicity of outcomes and are the grist for authoring a life. Like a flashlight, brightening some areas and leaving others dark, these five filters focus the mind in specific ways. They build positive, solution-oriented states of mind, which move us beyond distracting habits that protect our self-importance and offer ways to consider potential. All humans would benefit from this transformational framework that seeks adaptive, positive outcomes. Each one of us has internal resources we have not used. We all fail to notice signals that would increase awareness or consciousness. Most of us forget to consider options when we rush and would benefit from slowing down and perfecting our craft. And finally, professional allies open up possibilities that we had not considered. These mind states point toward positive futures in which we make choices that support our own growth and development. The true reflective practitioner sees the process of reflecting as self-authoring and delights when these processes become self-transforming.

Box 6.4 Seek Collective Efficacy—Five States of Mind

- ■ Efficacy: What resources might best assist us?

- ■ Consciousness: What are we becoming more aware of?

- ■ Flexibility: What other options should we consider?

- ■ Craftsmanship: What refinements might support us?

- ■ Interdependence: How can others support our success?

Reflection

A Place to Pause

iStock.com/BlackJack3D

- ■ Which state of mind might you choose to use to frame opportunities to observe yourself and others?

- ■ Which state of mind might best serve your thinking during teaching and learning?

- ■ How might these five states of mind help you accelerate learning?

This inquiry frame is actually quite complex, and we have found that learning how to use it skillfully takes lots of practice. One way we have accelerated learning is by creating lists of synonyms that can be used by a coach or a group to think about questions to expand thinking for each disposition. When working with groups, we often ask them to consider a problem, consider which state of mind would be the best point of reflection, and then to frame two or three questions to frame the inquiry (see Table 6.1 for more specific details).

The Transformative Act of Asking Your Own Questions

While working to train coaches, we were diligent in perfecting inquiry skills and often took groups through lengthy practice sessions. As we grew in our capacity to facilitate change, we realized that the real questions come out of the conversation, not some preconceived notion of pattern. Indeed, one of the most powerful reflective pauses can be to ask the person or group being coached to self-author their own next question by asking, “What questions are you asking yourself now?” Indeed, the cognitive shift is a signal to the coach to get out of the way of the other person’s thinking and to simply linger as they explain the shift in thinking.

The questions, which are self-authored, are exactly what are needed. They are real-time questions, not questions forced from a model. Consider this example. A friend was in the middle of coaching another, and he noted that the teacher seemed stuck; the teacher kept lamenting, “These mandates are stifling my creativity.” The coach kept thinking that the teacher lacked efficacy and focused his questions on “resources” with questions such as, “What resources have opened up your creativity in the past?” Then the coach finally thought to ask this teacher to self-author the next question; it made all the difference. The coach queried, “So based on what we are talking about, what question might you ask yourself?” The teacher stopped, looked into the distance for what seemed like forever, and then came back to the coach. Something had shifted inside—a cognitive shift moment. The teacher said, “At my other school, I worked on a wonderful team—we did everything together. Now I work with a team that does not like each other, so we do nothing together. The question I am asking myself is, ‘Where can I find a team to work with at this school?’” The coach was stunned; he would never have figured out that “interdependence” was the state of mind most needed at this moment. Reflective conversations create reciprocal learning; the learning goes on at all levels of understanding, and conversations that matter produce cognitive shifts for all.

For the purposes of this book, we do not have time to extend this chapter into two other models for reflective practice that have drawn from Cognitive Coaching and from which we have also learned much. The first is summarized in the book The Adaptive School: A Sourcebook for Developing Collaborative Schools (2016), articulated by Bob Garmston and Bruce Wellman to describe how the skills of Cognitive Coaching can be applied to group work. They both draw from their rich experience with facilitation groups and offer compendiums of adaptive strategies. The second is the work of Laura Lipton and Bruce Wellman, who have developed advanced processes for conducting learning-focused conversations (miravia.com). Each of these models draws from and reinforces the Cognitive Coaching skill set while adding additional practices from their extensive experience in training others.

Scenario 1

This example has been chosen to demonstrate the power of reflective practices to influence all parts of our lives. The story begins with a reflection conversation about a teacher new to special education teaching. The lesson had not gone well. Later, this day would be remembered as one of the worst days of her life.

To the teacher’s surprise, the supervisor began with the question, “So how did the lesson go?” Without realizing it, the teacher burst out, “The lesson did not go according to plan!” Two students in particular had been disruptive, and she had entirely left out one of the steps in the plan. In short, the lesson had been disorganized, and as a result, the students had been confused about expectations. As she talked, the teacher started to cry, and between the tears, she explained, “Last night I learned that a friend from college committed suicide. I would have stayed home, but I did not have any way to get lesson plans to the school.” (Note: This was before the Internet.)

A month later, the supervisor was back for another conference cycle and observation. In the planning conference, the teacher outlined what she expected to accomplish and was glad to have another opportunity to demonstrate her skills. After the lesson, she didn’t even wait for the supervisor to talk; she started out, “If I had to do it over again, I would have asked the students to review the directions before I asked them to move. Once I asked them to move, I had difficulty getting their attention back. Otherwise, I think the lesson went well.”

Two months later, the teacher began the reflection conference by saying, “Can I change what I wanted you to look at? I thought that the students would still have some difficulty with my instructions, but they didn’t. Now I am asking myself how I can get them more engaged in the tasks.” When she was asked to reflect on the year, the teacher responded, “When I did my student teaching, I only wrote plans when I knew I was being watched. I have learned that even if I do not write them down, I need to make plans in my head, and I need to mentally rehearse. If I do not do that, I sometimes forget important steps in my plan.” She went onto say that she was much more organized and that her mother had even noticed that she was planning for things in advance.

Scenario 2

While working as a superintendent, Diane decided to start a districtwide focus on writing. Rather than going outside to look for expertise, she started with her staff. She invited each school to pick two or three intermediate teachers that would be released to spend a day doing a writing audit. Teachers were instructed to bring anything that helped them explain what they currently used to teach writing.

Diane wanted to approach this session in an open-ended way and knew that as a newcomer to the district she would want to organize the audit as a listening opportunity for herself. She loosely structured the conversation using Cognitive Coaching as the framework. She took the group through the process, using questions to frame current goals and measures of success, stretch goals, and strategies needed. Together, they summarized their collective knowledge and identified gaps in their programs. Here are some of the questions she asked:

- ■ What are the teachers’ current goals for an intermediate writing program?

- ■ How do the teachers measure the success of the current writing program?

- ■ What are the stretch goals that teachers are currently working on, and what is keeping them from reaching those goals?

- ■ What are the next action steps you want to take individually?

- ■ What actions steps can the district take to support the teachers in achieving the next steps?

At the end of the day, the teachers had a clear set of outcomes that were needed to build a more robust writing curriculum. They agreed to inform the other teachers at their school what they had learned and to also seek ways to close the gap between existing and desired outcomes.

A few months later, Diane brought these same teachers together to learn about a writing program that one teacher had identified as meeting many of the needs listed earlier in the year. The teachers were so enthused by this opportunity, they insisted on a pretraining so that they could serve as lead teachers the following fall when the entire district would be involved. Diane reflects,

The power of the group to facilitate the change they needed was phenomenal. I could never have imagined the leap forward this group took and how quickly it impacted the entire district. Once again, it reminded me to slow down and really listen. When teachers are honest about what they know and do not know, they find the best path forward.

A Final Note—A Process of Inquiry That Will Demonstrate Cognitive Shifts

For over twenty years, we have used an Intervision process introduced to us by someone from Denmark. Unbeknownst to us, a similar process for problem solving can be found on the Web, with most of the references coming from European sources. Our process is different in that we only ask questions; we do not generate solutions. What we have found is that by asking questions only, we open many more options. We have also found just questions without answers help all focus on how the receiver responds to the question. It is a powerful practice exercise, as those questions that are most valuable to the receiver’s thinking show an obvious shift in expression.

The most powerful questions require that the other person break eye contact to think about the answer; it is in this pregnant pause that we notice the change in expressions. We now use this process regularly when working with adults on problems of practice. It demonstrates the power of some questions to make shifts and offers the gift of an unanswered question—which is a question we take away with us and ponder long after the session.

Intervision

We have used this as a warm-up for a meeting, using only one person’s problem. At other times we explore up to three people’s problems as a way to expand repertoire. It takes about twelve to fifteen minutes per problem. The process is as follows:

- ■ One person sits in front of the group and describes a professional problem, giving a brief description of the problem. The description should be just long enough to frame the problem, telling who, what, when, and where.

- ■ A short period is offered for participants to generate a few clarifying questions to make sure they understand the problem. Limit this time.

- ■ For the Intervision stage, participants pause and write down some questions they might ask about the problem from a point of exploration or curiosity. No embedded suggestions are allowed. (The Five States of Mind questions are invaluable for this process.) The aim is to ask thoughtful questions that will mediate thinking.

- ■ In pairs, the participants check each other’s questions to make sure they come from a point of not knowing—a point of curiosity. If a question has an embedded suggestion, the pairs rework it.

- ■ The person with the problem sits in a comfortable chair in front of the group, and participants take turns asking the questions. The person with the problem is instructed, “Go internal just long enough to think of the answer, then come back to the group; do not answer the question out loud.”

- ■ One person serves as scribe by writing down the questions as they are asked. As the participants observe the person’s response to each question, the scribe notes which questions have impact. This is easily discernable. Questions that do not require much thought, which do not have impact, are quickly answered, and the person returns to the center point, reestablishing eye contact. Questions that have impact, which produce a cognitive shift, require the person to stay in their mind longer and often get a discernable change in body language, maybe even a smile or head nod. When this happens, the scribe notes a star by the question and moves on.

- ■ Ask the person with the problem to quickly review the questions and tell why some of them had more impact and what his or her thinking is now about the problem.

What the group observes firsthand is how some questions seem to have ready responses and others cause the person to linger in thought longer. The questions are then given to the person with the problem so she or he can reflect on the important ones on her or his own time.