11 Frisk—Making Expectations Clear

Urban Luck Design, urbanluckdesign.com

Incredible change happens in your life when you decide to take control of what you do have power over instead of craving control over what you don’t.

—Steve Maraboli

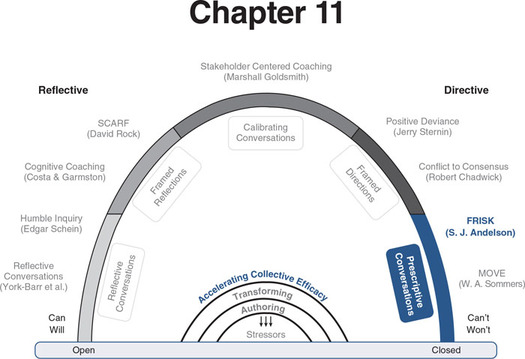

The originators of the FRISK model would likely be surprised to find their documentation guide in a book about conversations, and yet as we worked on the Dashboard, it became obvious that the tools provided by FRISK belonged on the arc as an invaluable tool for providing direct, candid feedback. Leaders must attend to employees who do not meet expectations; it is especially important for the success of conversations that appointed leaders manage problems that interfere with effective group work. When appointed leaders ignore bad behaviors, they lose respect from their constituents and also run the risk of having others join in the bad behavior. At some point, it is the appointed leader’s responsibility to step in and define expectations and then to hold participants accountable. This is where the FRISK model comes in.

The FRISKTM Documentation Model was developed as a communication tool to help promote positive change and correct misconduct. Developed by lawyers, its original purpose was to document the primary elements of just cause—the necessary information needed for termination in a progressive discipline system. The acronym reminds administrators of all the parts that need to be in a letter of warning or of reprimand.

The FRISK model is assertive, yet considerate in that it is both instructive and corrective. The facts are paired with a statement of rules that make the employee accountable. So while the supervisor takes responsibility for “telling” the employee what is wrong, the clear message then places the burden of improvement squarely on the employee’s shoulder.

Diane often found herself teaching this model to the administrators when it was time to document an employee’s problem behaviors. Over time, she also realized it was an effective way to provide verbal feedback—an early warning signal—to an employee that he or she was not meeting expectations.

There is no substitute for clear communication. This FRISK model provides a template for providing clear messages (see Box 11.1).

Box 11.1 FRISK: Acronym for Universal Components Needed for Just Cause

- ■ F—Facts that provide evidence of the conduct

- ■ R—Rule that establishes the authority

- ■ I—Impact of the behavior on the work environment

- ■ S—Suggestions for improvement and statement of expectations

- ■ K—Knowledge of the employee’s right to respond and provide corrective information

Diane has personally used this process both informally and formally and also has coached supervisors in how to use it with their employees. Here is an informal example from Diane’s work that explains the steps.

Informal Applications of FRISK

A ubiquitous problem on elementary playgrounds is teachers who do not show up for yard duty, despite repeated reminders. When it was brought to Diane’s attention that she had a repeat offender, she decided she could not ignore it. She asked to meet with the teacher after school about the duty schedule. Knowing that this teacher would have lots of excuses, she wanted to have his undivided attention when they talked. And she wanted him to know the topic in advance to provide him a chance to be reflective, if he chose.

When he arrived, he tried to act as if nothing was wrong. Diane asked him to sit down and then asked him to listen to all she had to say and that then he would be able to respond. Her speech went like this:

Today, you did not show up for yard duty at the 10:30 a.m. recess. (Fact) The schedule is published, and teachers are expected to show up or find another to cover. (Rule) When you don’t show up, you put the other teacher at a disadvantage; you are also negligent, and if someone was hurt, you would be liable and make the school liable as well. (Impact) I need you to tell me how you plan to make sure you do not forget this responsibility and that you will show up on time. (Suggestion for improvement) I consider the safety of our children so important that failure to comply will mean that I will put a formal reprimand in your personnel file. (Knowledge)

She finished with, “Now it is your chance to respond.”

The teacher started with an excuse—he had gone to the bathroom and then had run into another teacher and forgot to go to the yard. This required Diane to circle back and make a new rule that she expected him to follow. Diane explained that if both teachers had done this, the students would have been unsupervised. The rule she expected him to follow was to let his kids out a minute or two before the appointed time and to report to the playground. As soon as the other teacher arrived, he could excuse himself; but he needed to come right back. She then asked him what he needed to do so he would not forget the duty schedule. He decided that he should write his duty schedule on the chalkboard and ask his kids to help him remember.

Diane reflects on what really worked in this instance: Being nice did not work with this teacher, but being firm and clear did. She never had another problem.

Observable Facts—First-Person Data

One of the hardest parts of this process is getting firsthand facts. Legal advisors never want secondhand knowledge and so advise against hearsay. A principal friend of Diane’s once had two teachers report that they had witnessed a teacher roughly shaking a student outside the classroom door. The principal explained that she would need them to provide firsthand testimony and asked these teachers to go back to the teacher at fault. She coached them how to give an honest statement of facts to that teacher. She said, “Tell her the facts of your observation, then tell her the rule, which is that as professionals we cannot ignore abusive behaviors toward children, and then tell her that you have reported it to the principal.” In this case, the principal decided that a reprimand was in order, and because she had firsthand testimony to document the letter, her FRISK letter was well done and would have held up in a hearing. Fortunately, it never went to a hearing; the teacher shared that she was having personal problems and needed some time off to sort things out. She asked that this be shared with her teammates, and all were grateful that she would take care of her own mental health first. She came back later and retired two years after that.

Likewise, in order to solve the problem with the yard duty schedule, Diane needed her staff members to report on their peers. She used FRISK to help the teachers understand why being nice and covering for another teacher was negligent. As you read along in Diane’s example that follows, label the parts of FRISK. At a staff meeting, Diane laid out her expectations:

We have a problem. It has been reported to me more than three times in the last month that teachers have failed to show up for yard duty. It is a contractual obligation that teachers complete “other duties as assigned.” Failure to report another teacher is negligent. I want to make the impact of being nice to a colleague clear. When you stand out there alone and fail to act, you are negligent, and you also make the school negligent. This is not about being nice; this is about being responsible. If a teacher is not on the yard soon after the recess starts, please send a student runner to the office to report the absence. Someone will cover until the teacher is located.

What she did not tell the teachers, she told her office staff. When a student came to report a “failure to show,” they needed to contact Diane immediately so that she could go the yard and cover. This also gave Diane that valuable firsthand information. Diane laughs, “For 90 percent of the teachers, this was enough. For that one teacher, he needed to be FRISKed in order to get the message.”

Having open, candid conversations with staff about these kinds of problems and helping them understand that it is once again everyone’s responsibility to be accountable contributes to the overall cultural value for open, honest communication. Learning how to give difficult messages is a necessary skill. Administrators need it, teachers need it, and Diane has even taught parents to use it. The French have a proverb: “Children need models more than critics.” The students need models for how to deal with difficult situations.

A Fair Shot at Improvement

While this meets the legal requirement for documentation should the supervisor need to terminate the employee, it also gives the employee a fair shot at improvement. It is positive in that it makes clear what the expectations are and lists corrective action that gives the employee a chance to commit to change. Indeed, we have found that when an employee understands and accepts the expectations there is usually improvement; however, if the employee does not seem to hear the message and argues to defend behaviors, changes usually do not occur. This is a pivotal point in the relationship, as when no change is forthcoming, it may mean that it is time for the employee to move on, which is the topic of the next chapter.

Typically, following a progressive discipline procedure, this type of a conversation may be held several times in an attempt to help the employee improve. The supervisor has to decide if the effort to improve the behavior is worth the time invested. In some organizations, such as public employee unions, the discipline needs to be progressive, in that the first time might be a verbal warning.

Reflection

A Place to Pause

iStock.com/BlackJack3D

As professionals, we often state that we want to have open, honest, and candid conversations with peers, and yet, we avoid them.

- ■ How might you apply FRISK to communicate a concern with a colleague?

- ■ Which parts of the FRISK conversation are most difficult, and what does that tell you about your relationship with candor?

- ■ How might you apply FRISK in a future conversation? Jot down some reminders or mentally rehearse so you are ready when need be. These conversations work best when they occur soon after the offending behavior.

Formal Application of FRISK—Documenting the Problem

F—Facts

At this point in the communication, the message needs to be explicit and observable with appropriate examples. It should tell what, when, where, and how the facts were gathered. To illustrate the steps, here is an example of the application. This needs to be a first-person report and not anonymous. It should not include belief statements or other justifications. It should state just the facts, as this example shows:

On April 1, 2017, you came into the office at X school and told the secretary, XX, that you had looked her up on a dating website. You then asked if she had met anyone “hot.” The phone rang, and then you left. The next day you came back in the office and said that you had told a friend that she was “hot” and that he should look her up. XX was embarrassed by your comments and told you her dating life was private. For the next week, you continued to pester her each afternoon, asking her if she had any “hot prospects.” XX says she tried to ignore you. She was finally fed up and complained to me.

R—Rule

Stating the rule is easy if there is a clear violation of a written guide, such as a board or administrative policy, an employee contract, professional standards, or other such document. If this is not the case, a rule can be established that then becomes a standard by which all future behaviors will be measured. In the previous example, the behavior had become harassing in that it was unwelcome and repeated. Most workplaces have rules about harassment. While the sexual innuendo seems clear here on paper, the employee later pled that he was “just trying to be friendly.” He also thought because she was on a dating site, that made it public. To avoid any future confusion, it is time to make a clear rule that will become the new standard of behavior.

The behavior described here has occurred over time and has sexual overtones. If it continues, you will be violating the Board and Administrative Policies (list numbers for harassment and sexual harassment). Furthermore, online dating sites are designed for adults to meet other like-minded adults; they are not to be thought of as a way to delve into another’s private life during work time. We expect employees to be professional and to give other employees the respect they would want for themselves. This means that what you learn about others on the Internet on your own time should not be brought into the workplace. You would not want others talking about your dating life, and you need to show others the same respect.

I—Impact

This is the first time the supervisors can weigh in with their own feelings and beliefs. At this point, they should start with the larger impact statement for the organization, but they can also include their own values and beliefs.

This is the kind of behavior that eventually leads to a hostile work environment as addressed in Board and Administrative Policies (list numbers for policies on hostile work environment). XX was very upset about your insinuations about her dating life and does not think she can work with you. As a custodian, you need to be able to work with the secretary, and she needs to be assured that you will not bring up personal topics of conversation. As a woman, I am also offended by your behavior in that describing a woman as “hot” treats her as a sexual object, not with the respect she deserves.

S—Suggestions

This is best considered as a “needs” statement in that it describes what you need them to do. It should also be thought of as a chance to teach about policies or other written documents used to guide behaviors. By taking time to teach, you are verifying that this person now understands the rules.

I am providing you with the written policies so that you are well informed about the implications should you continue or repeat this behavior. In addition to improving the working relationship, she needs to be assured that you will not harass her further. From now on, you will need to clean the office after the staff has gone home, and when you come to the office, it will need to be for business purposes only.

K—Knowledge`

This is the part that provides the due process protections. Not only have you informed them of the problem, but you are now telling them the consequences of their action. You are also telling them that this is their chance if they want to clarify or rectify anything with you. This is an important conversation, and often, there are contractual or policy procedures in place. For example, in some districts the employees need to sign to indicate that they have been informed of their rights.

The fact that we have written policies about sexual harassment means that we take this misconduct seriously. For this reason, I will be placing a written summary of these statements in your personal file, and as per (list policies or contractual requirements), you have a right to respond in writing as outlined in that document.

The FRISK model makes what would normally be a difficult conversation manageable. In most cases, it provides a civil way for the employer and an employee to meet and confer about a problem. Sometimes, employees can be less than grateful and begin to verbally attack or blame the supervisor. Once again the FRISK process assists the leader in staying on topic. When the employee attacks, the administrator can respond, “I know you are upset about this meeting, but attacking me does not solve the problem. If you think there is something we could have done differently, you can put it in writing as part of your response.” This allows the supervisor to stay out of an argument with the employee.

Scenario 1

Interventions done early are always better than ones that occur after a longer period of the behavior. If the principal had become aware of the custodian’s behavior when it first happened, she could have had the female employee use a modified FRISK message. It would have been a direct message and would have gone something like this.

Yesterday, you came in here and started talking about my dating life and the website I use. I need to set a rule about our conversations at work. I do not talk about my dating life at work. It embarrasses me when you talk about me being “hot.” I also do not like you meddling in my dating life. I need to know that you will stop telling friends about me and also stop talking about this with me at work. Will you do this?

This intervention likely would have stopped the behavior, and if it didn’t, it would give the supervisor more information about how inappropriate this custodian was, despite warnings. It would have also saved this female employee from the distress she suffered as a result of his harassment. She had a great deal of emotional distress about this episode, and it took a lot of work to help her understand that this was a first warning and that they would have to have conversations from time to time, as that was the nature of the job.

Scenario 2

Diane used this process to facilitate a conversation that came up at a staff meeting about the norms. It turns out that one of the more senior teachers was upset that so many teachers brought other work to the staff meetings. She wanted to make a rule that staff could not bring other work to the meeting. This created quite a debate. Just looking around the room gave the facts. One teacher had a stack of papers to grade, another was knitting a shawl, another brought stationery and wrote notes to her kids, and so forth. Here is how the FRISK process worked in this meeting.

The facts were obvious; staff members did bring other things to do. The problem was there was no consensus about the rule. Some thought it was fine to not allow outside work; some were offended that others wanted to control their behavior. (Note: The SCARF themes of status and autonomy are playing out here as well.)

The valuable part of this model came with the honest discussion of impact. It turns out that the teacher with the concern felt that it was disrespectful to Diane for staff members to do other work. It did not demonstrate listening. Those that did other work pointed out that their work, such as the knitting or grading of math papers, allowed them to listen and work. Others indicated that not all agenda items were of equal value and that they should be allowed to do other things as long as they did not distract others. Diane finally had to admit that she was one of those who brought work to the meetings she attended.

As they talked, it became clear that there were times in staff meetings that Diane didn’t need every teacher’s attention; but they often used staff meetings for important conversations. Indeed, this conversation was one of them—everyone was engaged. They agreed on a rule. Staff members could bring other work to meetings, and when Diane needed all the staff to be engaged, she would tell staff it was time to put away their projects and to focus. They would check in to see how the rule was working at future meetings.

Diane said the rule worked like a charm. It was a win–win. The solution respected autonomy and also showed respect when needed.