INFORMATION AND PERMITS: These trips are in Yosemite National Park: wilderness permits and bear canisters are required; pets and firearms are prohibited. Quotas apply, with 60% of permits reservable online up to 24 weeks in advance and 40% available first-come, first-served starting at 11 a.m. the day before your trip’s start date. Fires are prohibited above 9,600 feet. See nps.gov/yose/planyourvisit/wildpermits.htm for more details.

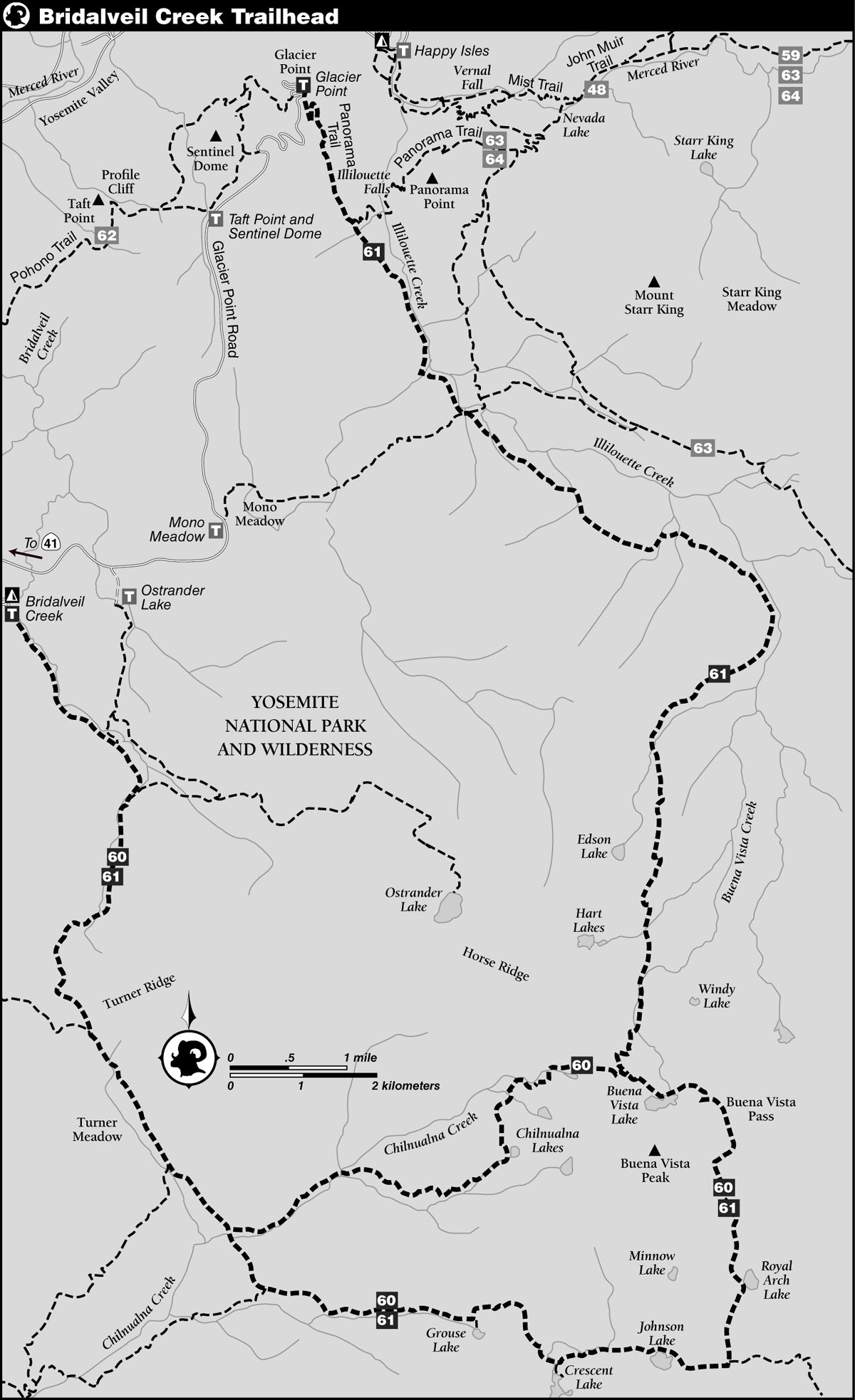

DRIVING DIRECTIONS: From a signed junction (Chinquapin Junction) along Wawona Road (CA 41), drive 7.8 miles on Glacier Point Road to the entrance road to Bridalveil Creek Campground; this is 7.9 miles before Glacier Point. Turn right onto Bridalveil Creek Campground Road and follow it past the camping loops. The trailhead is on your right at a tiny lot with room for perhaps three cars, just before the road crosses Bridalveil Creek.

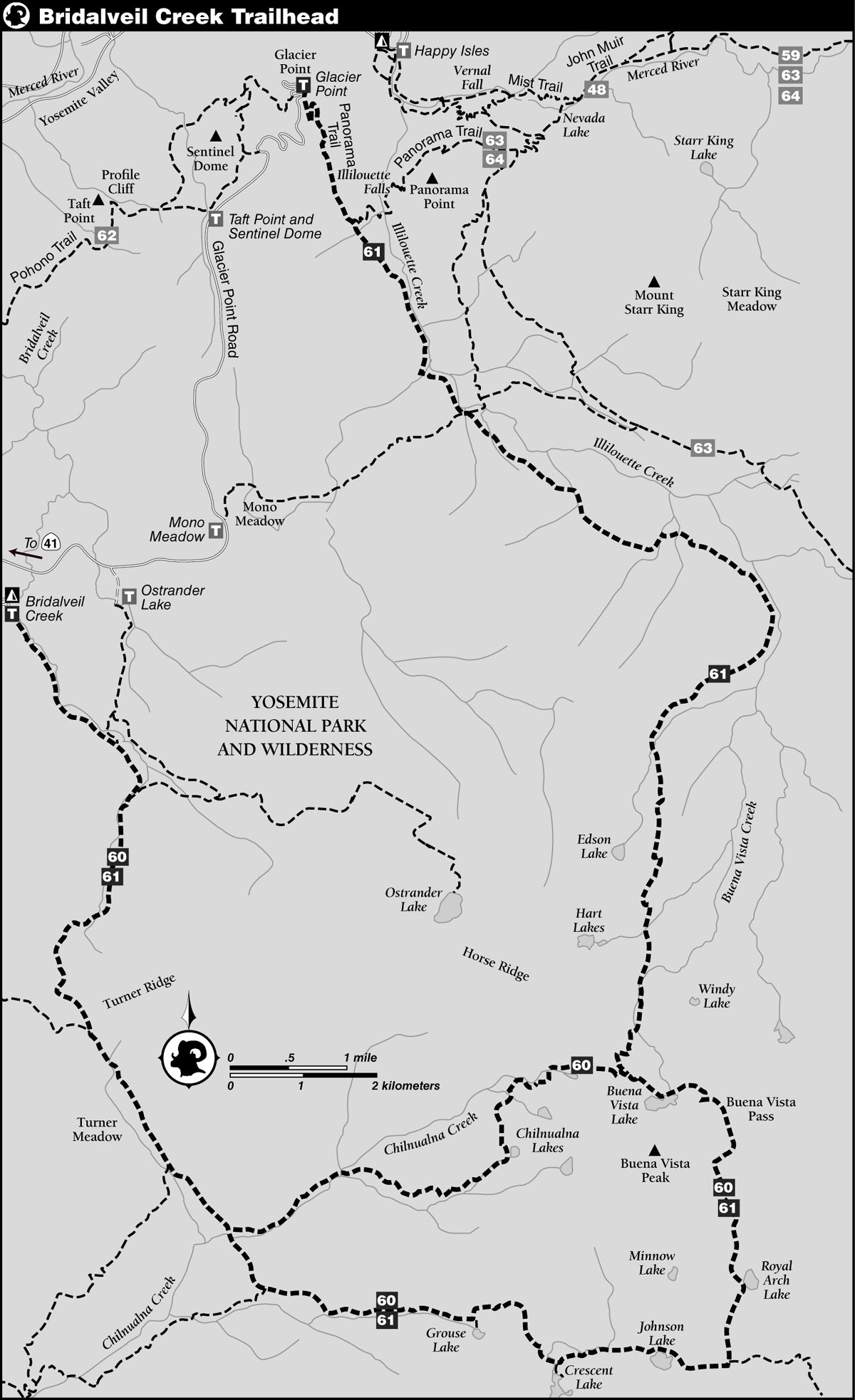

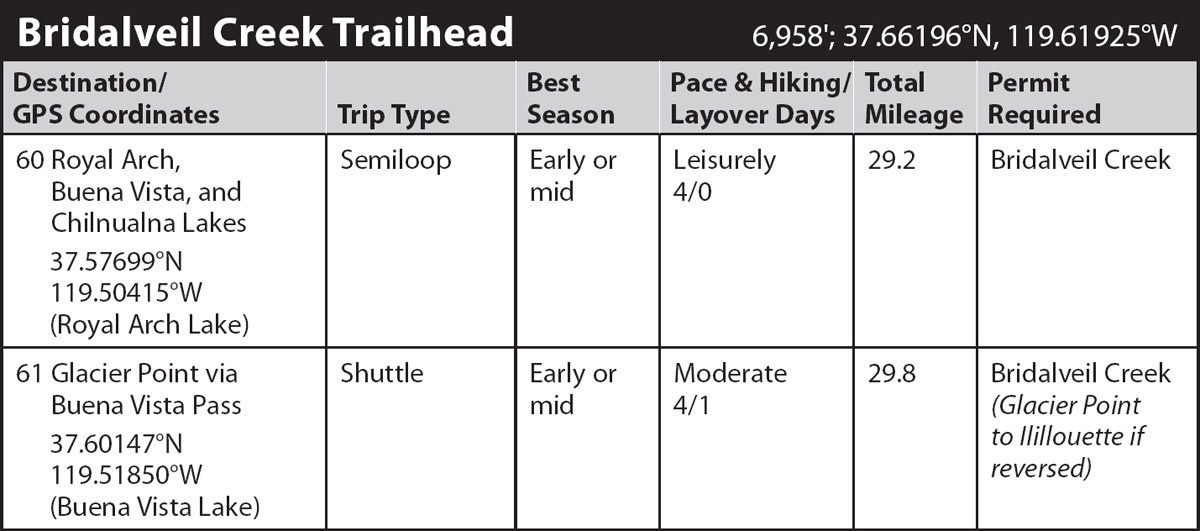

trip 60 Royal Arch, Buena Vista, and Chilnualna Lakes

Trip Data: |

37.57699°N, 119.50415°W (Royal Arch Lake); 29.2 miles; 4/1 days |

Topos: |

Half Dome, Mariposa Grove |

HIGHLIGHTS: In early season, this route is lush with wildflowers of every variety (and unfortunately mosquitoes); the fishing at Royal Arch Lake is excellent. The generally gentle grades make this a fine early-summer choice as you’re getting in shape for the summer.

HEADS UP! The mileage includes the distance along short spur trails to reach Grouse, Crescent, and Johnson Lakes—a grand total of 0.9 mile extra over skipping the lakes. It is strongly recommended you visit these lakes because you barely notice them from the trail.

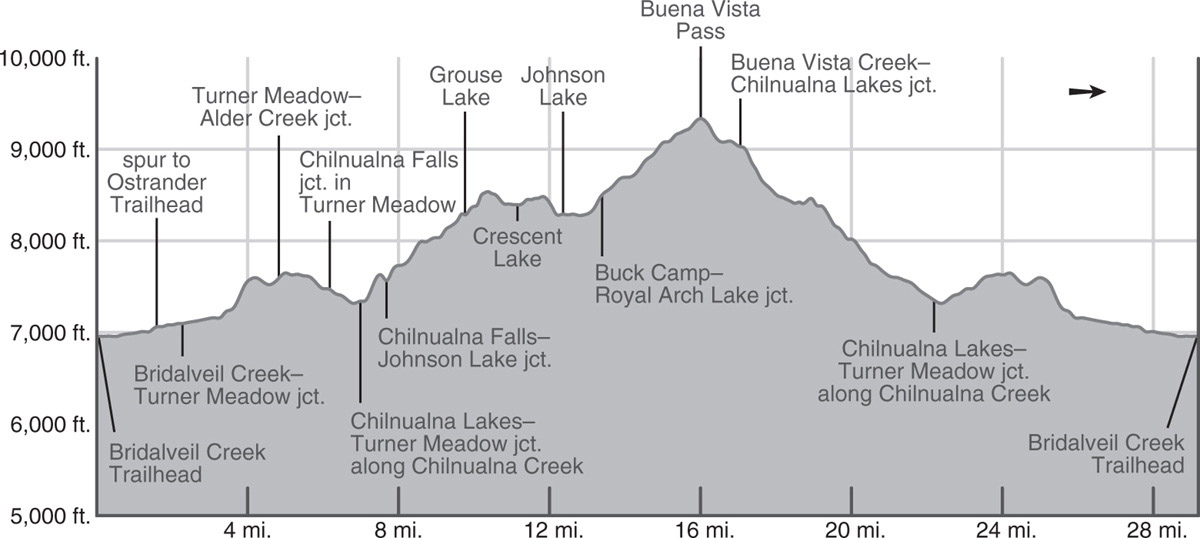

DAY 1 (Bridalveil Creek Trailhead to Turner Meadow, 5.9 miles): From the trailhead at the far southeastern corner of the Bridalveil Creek Campground (and just before the road fords Bridalveil Creek to the stock camp), the unmarked and little-used trail begins winding along meandering Bridalveil Creek’s western bank. It is a lush streamside walk through dense lodgepole forest that periodically opens into intimate meadows filled with shooting stars. The grade is delightfully gentle—you climb just 100 feet in the 1.6 miles to a junction with a spur that hooks sharply left (north) to cross Bridalveil Creek and shortly meet the Ostrander Lake Trail; you stay right (south).

Beyond, the trail veers south beside one of the larger tributaries of Bridalveil Creek. It crosses this tributary on a log and immediately meets a lateral left (northeast) to the Ostrander Lake Trail; again, you trend right (west). The verdant banks are thick with wildflowers, with the lavender shooting stars, elephant’s head, and giant red paintbrush among the most evocative. The gradual climb along the creek corridor continues through the burned remnants of a red fir and lodgepole pine forest, the damage caused by the 2017 Empire Fire. Sections of forest are decimated, while elsewhere stands of trees have survived, likely because the expansive meadows and bald sandy areas in the drainage helped curtail the fires’ spread. After another mile, you cross the now smaller (and seasonal) tributary, where there are (somewhat burned) campsites when there is water.

The second ford marks the beginning of an easy, 400-foot climb over the unglaciated ridge that separates the Bridalveil Creek and Alder Creek watersheds—and indeed the main Merced and South Fork Merced drainages. The Empire Fire did not spread south here and ahead the canopy is again green. From the top of this ridge, where you can glance east toward Mount Starr King, the trail drops south-southeast to meet the trail that leads right (west) to Deer Camp and Empire Meadows. Continuing straight ahead (left; southeast), climb just briefly, then cross a small creek, and follow a shelf that overlooks Turner Meadow. In early season, you’ll ford many little rills, all with abundant corn lilies, as you descend to Turner Meadow. Wildflowers are abundant in early season—and so are mosquitoes.

Just before the ford of a sizable tributary (7,475'; 37.59605°N, 119.59705°W), there’s a large packer campsite on your right (southwest) in the trees fringing the meadow. Farther ahead is another site in a slender, open, sandy flat. Make some time to sit quietly by the meadow, especially in the early morning, to see wildlife.

DAY 2 (Turner Meadow to Royal Arch Lake, 8.2 miles): Resume your descent down the long, gently sloping Turner Meadow and soon meet a trail coming across from Chilnualna Falls and Wawona. At the junction, you go left (southeast), continuing through moist lodgepole forest, and in 0.9 mile reach a junction (and an alternative creekside campsite for your first night). Left (east) leads to the Chilnualna (chill-NWAHL-nah) Lakes, your return route, while you turn right (south) and immediately ford swirling Chilnualna Creek on a cobbled base (can be difficult in early season). From the ford, climb southeast on switchbacks over an eastward-rising ridge and down to a junction; here a second lateral trail leads right (west) to Wawona, while you turn left (eastward), signposted for Buck Camp.

Climbing Buena Vista Pass Photo by Elizabeth Wenk

You are paralleling a small tributary of Chilnualna Creek east. Initially your route follows a gully north of the creek corridor, passing a flat that was scarred but not decimated by the 2017 South Fork Fire, then you are channeled up a second shaded gully before finally dropping to the unnamed creek. Quickly exiting the burn zone, you continue upstream for about a mile to a junction with a hard-to-spot spur trail leading 300 feet right (south) to little Grouse Lake and campsites; this junction is located where the main trail turns sharply left.

Back on the main trail, a slightly steeper ascent leads to drier terrain atop a small rise, from which the trail drops southward, then briefly eastward, to ford the inlet of shallow Crescent Lake, just out of sight to the south. Just past the crossing, a minor trail heads south 0.15 mile to the lakeshore and campsites. This spur, like those to the other nearby lakes, is included in the daily mileage, to ensure you’ve budgeted the time to visit them, for just out of sight of the trail they are easy to forgetfully bypass—and yet aren’t they part of the reason for taking this walk? Grouse, Crescent, and Johnson Lakes all sit on a relatively flat bench high above the South Fork Merced River. Each is drained by a separate creek flowing into the South Fork Merced—those exiting Crescent Lake and Johnson Lake drop steeply to the west. At Crescent Lake, you might visit or camp near the lake’s south end, for, from its outlet, you can peer into the 2,800-foot-deep South Fork Merced River Canyon.

Eastbound again, another 0.9 mile of level walking through often mosquito-infested forest with superb wildflower patches, brings you to a junction with a spur leading south to Johnson Lake’s west shore and more campsites. For the September hiker there is an extra treat—western blueberries. Johnson Lake and its perimeter were one of the last acquisitions of private property within the park’s boundaries, and two crumbling cabins remain to remind you of the homesteading era.

The next 0.8 mile is a 170-foot ascent up a lodgepole-covered slope alongside Johnson Lake’s inlet stream, the ground sporting expanses of corn lilies and shooting stars in June and July. At a junction you turn left (north) toward Royal Arch Lake, while right (east) leads to Buck Camp, a summer ranger station.

ROYAL ARCH?

This lake probably got its name from the arching pattern of exfoliation on the granite dome on the lake’s east side, which strongly resembles that of the famous Royal Arches—also exfoliation features—in Yosemite Valley.

The dense forest almost immediately gives way to more open, drier walking as the trail trends along benches on an open hillside. The landscape flattens as you approach dramatic, small, deep Royal Arch Lake. The best campsites are in the forest fringe on the lake’s south shore (8,695'; 37.57699°N, 119.50415°W). Fishing is good for rainbow and brook.

DAY 3 (Royal Arch Lake to Lowest Chilnualna Lake, 5.1 miles): From Royal Arch Lake, resume your northward climb, traversing an idyllic meadow and fording its creek just below Buena Vista Pass on Buena Vista Peak’s northeast ridge. Along the creek corridor are additional campsites as long as water is flowing.

CLIMBING BUENA VISTA PEAK

From the pass (9,340'), it is an easy 0.75-mile climb to the top of aptly named Buena Vista Peak (9,709'). As the highest point for miles around, this peak offers some of the most expansive views in this part of the Sierra. Since this day is the trip’s shortest, you should have ample time for this detour, simply following the ridgeline southeast to the peak. Sandy walking transitions to broken slab and then to talus for a short distance before the summit.

From the very gentle pass, the trail descends more steeply, crossing through a streamside pocket meadow and presently reaching deep, rugged Buena Vista Lake—dramatically situated beneath its namesake peak and offering several very scenic campsites in sandy patches between stunted lodgepole pines. The temptation to cut the day short and stay here is almost irresistible.

Resisting, you skirt the lake’s north shore and descend to a junction with views extending to Half Dome and Mount Hoffmann to the north and the Clark Range to the east. The right fork descends generally north into the drainage of Buena Vista Creek, on its way to Glacier Point (Trip 61), while you take the left fork westward. It drops just over 400 feet across broken slabs, dotted with clusters of lodgepole pines and solitary junipers, to reach the northernmost of the Chilnualna Lakes. Lying at the headwaters of Chilnualna Creek, each of these little lakes is forested and meadow edged, and each has a good campsite. Fishing is good for brook and rainbow except at the lowest lake. The trail skims the shores of this northernmost lake and, later on, the lowest lake. The other two Chilnualna Lakes are off-trail and, especially the southernmost one, offer better and more secluded camping if you’re up to the cross-country leg to get to them.

In denser, damp forest now, trace the northernmost lake’s outlet for a short distance before stepping over it and curving south, then west, and finally south again on a pleasant ramble that’s mostly a gentle descent. It’s not long before you step over the off-trail middle lake’s outlet (following it is a possible route to that lake). Going west then south from here, you skirt a small meadow, and climb over a low bouldery morainal ridge to reach the lowest lake with good campsites on its north side (8,380'; 37.59320°N, 119.54127°W). This little lake is quite shallow and is one of this trip’s warmest lakes for a dip.

DAY 4 (Lowest Chilnualna Lake to Bridalveil Creek Trailhead, 10.0 miles): From the lowest Chilnualna Lake, resume your gentle, forested descent just out of sight of its outlet creek. After 0.4 mile, where the trail curves west, you step across the outlet creek and traverse out of the lush riparian corridor onto a drier slope, a bouldery ridge that is a recessional moraine. You follow it for 1.4 miles toward the confluence of your outlet creek and Chilnualna Creek proper (the outlet creek of the northernmost lake). Cross Chilnualna Creek on rocks, another tributary on a log, and continue down the drainage, alternating between lush red fir and lodgepole forest and open stretches full of slabs. The moist areas have spectacular wildflowers in late June and early July—alpine lilies, crimson columbine, violets, shooting stars, and larkspur to name just a few. Trending more westerly, away from the creek, exactly 3 miles below lower Chilnualna Lake, you reach the junction where you began the loop part of this trip on Day 2. Turn right (northwest) toward Turner Meadow and retrace your steps of Day 1 and part of Day 2 to the trailhead.

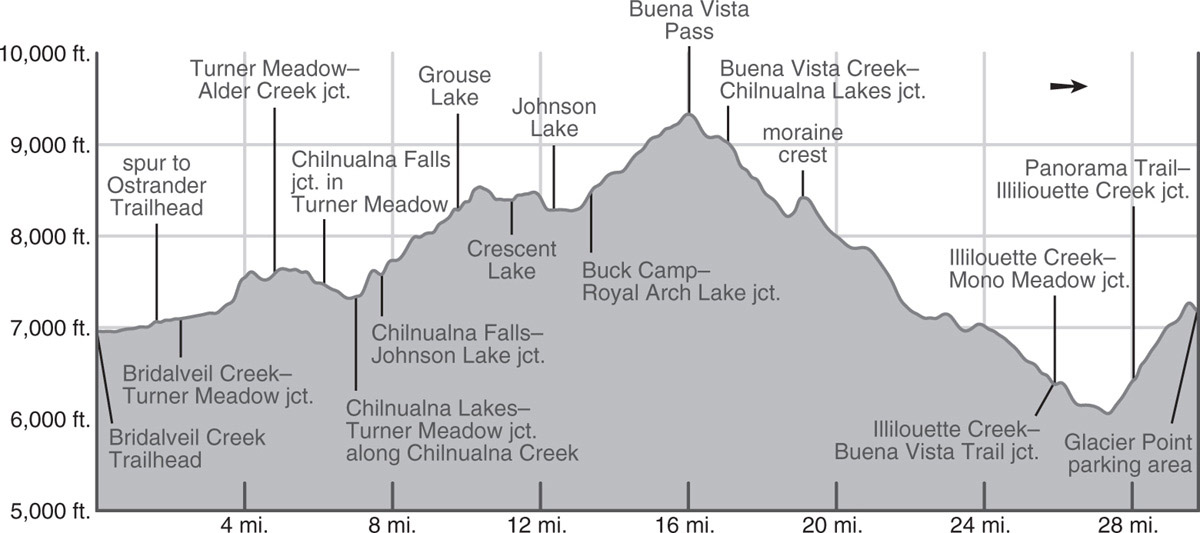

trip 61 Glacier Point via Buena Vista Pass

Trip Data: |

37.60147°N, 119.51850°W (Buena Vista Lake); 29.8 miles; 4/1 days |

Topos: |

Half Dome, Mariposa Grove, Merced Peak (just barely) |

HIGHLIGHTS: On this trip, early- and midseason travelers will find splendid forests, lush meadows, delightful wildflower displays, beautiful creeks, and excellent angling, all topped off with vistas of Yosemite’s famous scenery. It also makes a beautiful late summer or fall trip, but water sources will be more limited, so plan to camp by a major creek or lake.

SHUTTLE DIRECTIONS: The endpoint is Glacier Point, located at the terminus of the Glacier Point Road. To reach it, from the starting trailhead, drive back out of the Bridalveil Creek Campground to the Glacier Point Road and continue an additional 7.9 miles east and north along it to a large parking area. The Panorama Trail, on which you finish, enters the maze of trails at the far southeastern corner of the Glacier Point environs, near the amphitheater.

HEADS UP! The mileage includes the distance along short spur trails to reach Grouse, Crescent, and Johnson Lakes—a grand total of 0.9 mile extra over skipping the lakes. It is strongly recommended you visit these lakes, because you barely notice them from the trail.

DAY 1 (Bridalveil Creek Trailhead to Chilnualna Creek, 7.0 miles): Follow Trip 60, Day 1, which leads you 5.9 miles to Turner Meadow (7,475'; 37.59605°N, 119.59705°W). Then continue an additional 1.1 miles, described here.

Just before the ford of a sizable tributary, there’s a large packer campsite on your right (southwest) in the trees fringing the meadow. Farther ahead is another site in a slender, open, sandy flat. Continuing your descent down the long, gently sloping meadow, you soon meet a trail coming across from Chilnualna Falls and Wawona. At the junction, you continue left (southeast), onward through moist lodgepole forest and in 0.9 mile reach Chilnualna Creek and a beautiful creekside campsite (7,345'; 37.58448°N, 119.58477°W) near a junction.

DAY 2 (Chilnualna Creek to Buena Vista Lake, 9.8 miles): Back at the nearby junction, left (east) leads to the Chilnualna Lakes and would be an alternative, much shorter route to Buena Vista Lake, while you turn right (southeast) and immediately ford swirling Chilnualna Creek on a cobbled base (crossing can be difficult in the early season). From the ford, climb southeast on switchbacks over an eastward-rising ridge and down to a junction; here a second lateral trail leads right (west) to Wawona, while you turn left (eastward), signposted for Buck Camp.

You are paralleling a small tributary of Chilnualna Creek east. Initially your route follows a gully north of the creek corridor, passing a flat that was scarred but not decimated by the 2017 South Fork Fire, then you are channeled up a second shaded gully before finally dropping to the unnamed creek. Quickly exiting the burn zone, you continue upstream for about a mile to a junction with a hard-to-spot spur trail leading 300 feet right (south) to little Grouse Lake and campsites; this junction is located where the main trail turns sharply left.

Back on the main trail, a slightly steeper ascent leads to drier terrain atop a small rise, from which the trail drops southward, then briefly eastward, to ford the inlet of shallow Crescent Lake, just out of sight to the south. Just past the crossing, a minor trail heads south 0.15 mile to the lakeshore and campsites. This spur, like those to the other nearby lakes, is included in the daily mileage, to ensure you’ve budgeted the time to visit them, for just out of sight of the trail they are easy to forgetfully bypass—and yet aren’t they part of the reason for taking this walk? Grouse, Crescent, and Johnson Lakes all sit on a relatively flat bench high above the South Fork Merced River. Each is drained by a separate creek flowing into the South Fork Merced—those exiting Crescent Lake and Johnson Lake drop steeply to the west. At Crescent Lake, you might visit or camp near the lake’s south end, for, from its outlet, you can peer into the 2,800-foot-deep South Fork Merced River Canyon. Indeed, if you have time to make this a 5-day trip, a night at Crescent Lake or Johnson Lake is recommended as soon as the mosquito population moderates.

Eastbound again, another 0.9 mile of level walking through often mosquito-infested forest with superb wildflower patches, brings you to a junction with a spur leading south to Johnson Lake’s west shore and more campsites. For the September hiker there is an extra treat—western blueberries. Johnson Lake and its perimeter were one of the last acquisitions of private property within the park’s boundaries, and two crumbling cabins remain to remind you of the homesteading era.

The next 0.8 mile is a 170-foot ascent up a lodgepole-covered slope alongside Johnson Lake’s inlet stream, the ground sporting expanses of corn lilies and shooting stars in June and July. At a junction you turn left (north) toward Royal Arch Lake, while right (east) leads to Buck Camp, a summer ranger station.

The dense forest almost immediately gives way to more open, drier walking as the trail trends along benches on an open hillside. The landscape flattens as you approach dramatic, small, deep Royal Arch Lake. The best campsites are in the forest fringe on the lake’s south shore. Fishing is good for rainbow and brook.

From Royal Arch Lake, resume your northward climb, traversing an idyllic meadow and fording its creek just below Buena Vista Pass on Buena Vista Peak’s northeast ridge. Along the creek corridor are additional campsites as long as water is flowing. From the very gentle pass, the trail descends more steeply, crossing through a streamside pocket meadow and presently reaching deep, rugged Buena Vista Lake—dramatically situated beneath its namesake peak and offering several very scenic campsites in sandy patches between stunted lodgepole pines to either side of the trail (9,903'; 37.60147°N, 119.51850°W; no campfires).

DAY 3 (Buena Vista Lake to Illilouette Creek, 9.1 miles): In the morning, skirt the lake’s north shore and descend to a junction where left (west) leads back to Turner Meadow via the Chilnualna Lakes (Trip 60), while the right (north) fork, your route, descends generally north into the drainage of Buena Vista Creek. From the junction the view extends to Half Dome and Mount Hoffmann to the north and the Clark Range to the east—a vista you’ll be enjoying repeatedly on today’s walk.

View east to Half Dome, Vernal and Nevada Falls, and up the Merced River drainage from the Panorama Trail Photo by Elizabeth Wenk

Turn right and descend steeply down a short headwall to two ponds (possible campsites) and into the Buena Vista Creek canyon. After crossing Buena Vista Creek several times, the trail trends north away from the drainage, crosses a shallow saddle (with a possible campsite) and descends into the valley draining Hart Lake’s outlet creek. Crossing this creek, the trail now climbs dry, scrubby slopes up the eastern face of a large moraine, the ascent boasting outstanding views of the Clark Range. West of the moraine crest, the trail begins a gentle descent down sandy slopes and through scattered red fir stands, until, 1.25 miles north of the moraine crest, you suddenly enter burned forest—a flat of logs and regenerating trees, the result of the 2001 Hoover Fire. A little beyond, you cross the seasonal outlet from Edson Lake between two wet meadows (there are good campsites at the lake).

Turning northeast, the grade soon steepens, and the trail descends over indistinct glacial moraines, all the while walking through a mostly burned landscape—indeed for the next 5 miles the trail passes continually through landscape burned in at least one blaze in the past four decades. The 1980 Fat Head and 1981 Buena Vista Fires were the first to burn some proportion of the trees here, while the area was, in part, retorched in 2001, 2004, and 2017. Until you are close to Illilouette Creek, stretches of intact forest are rare, with the landscape, in many places, crisscrossed by downed logs and carpeted in dense shrubs or thickets of young trees.

As the trail nears the sometimes seasonal Buena Vista Creek, stare down the remarkably steep escarpment to the creek below. Notice the giant boulders at the channel’s edge and the cobble bars, all evidence of long-ago floods. The trail then turns westward and climbs gently as it passes through a lovely stand of dispersed, stately Jeffrey pines, then crosses a broad flowery meadow at the head of a seasonal tributary; there are some splendid campsites northeast of the trail near the first creek crossing where some stands of trees remain. The bald dome rising across the drainage is Mount Starr King.

FIRE AND TREES

Fire is a natural part of the ecology of the Sierra’s midelevation coniferous forests, with the fires generally ignited by lightning strikes. Historically, fires were frequent and mostly burnt at low intensity, preventing a large buildup of dead wood, which in turn prevented subsequent fires from reaching severe intensity and killing the canopy trees. Unfortunately, a century of fire suppression (putting out every fire that ignited) led to dense understory growth and the accumulation of dead wood, such that when fires have ignited in the past 30–40 years, they have been increasingly catastrophic for the plant community. Along this stretch of trail there are only a few patches of intact forest that escaped the flames, and the conifer forest will take at least a century to reestablish. However, the fires have created an elegant mosaic of trees’ ages, openings filled with spring wildflower displays, and have spared enough mature trees that there is still a local seed source.

Following fires, lodgepole pines are the first to appear, germinating quickly and profusely and producing cones after about 20 years. The trail passes through one dense thicket of lodgepoles that are just starting to reproduce—as long as another fire doesn’t again reset the successional clock before you walk the trail. In time, this thicket will thin and later-germinating conifers, such as fir and Jeffrey pine, will begin to mature.

Climbing gently, the trail passes through a thicket of young lodgepole pines and drops into the drainage of another Illilouette Creek tributary, descending along its margins. Most of the landscape here has been well charred, and dense shrubs, especially whitethorn, encroach rapidly on the trail between trimmings. There are a few places to camp, but better sites await along Illilouette Creek. As you approach this trail junction you walk past a beautiful forest with several giant sugar pines, survivors of many fires over the centuries. At the trail junction, turning right (east) leads to some beautiful, albeit well-used, campsites to either side of the trail just before a ford of Illilouette Creek (6,396'; 37.68641°N, 119.54685°W).

Leichtlin’s mariposa lily grows in dry, sandy areas. Photo by Elizabeth Wenk

DAY 4 (Illilouette Creek to Glacier Point, 3.9 miles): Returning to the junction with the Buena Vista Trail, head right (north), signposted for Glacier Point. After just 100 feet, you reach a second junction, where left (west) leads to Mono Meadow (an alternate ending point), while you turn right (north-northwest), soon descending more steeply down a mostly open slope back toward Illilouette Creek. At 0.6 mile from the last junction, just as you approach Illilouette Creek’s banks, you ford the creek descending from Mono Meadow.

For nearly a mile you now descend parallel to Illilouette Creek as it winds through a gorge, a most spectacular experience. There are cascades; big, deep pools; mill holes in rocks created by the churning water; and smooth, giant boulders. Pink and yellow azalea flowers grace the banks. Although you pass some attractive riverside benches, camping is not permitted here. Leaving the river corridor, the trail begins to ascend a steep sandy slope through firs, manzanita, and spiny chinquapin, leading to a junction with the Panorama Trail.

From here you have 1.75 miles remaining to the Glacier Point parking area and another 800 feet of ascent. If you have time and energy and water flows are still decent, a detour to the top of Illilouette Fall is highly recommended—although be forewarned the viewpoint does require an extra 400-foot descent and ascent.

ILLILOUETTE FALL VISTA

To reach the Illilouette Fall vista, from the junction where you meet the Panorama Trail, head down (right; northeast) five switchbacks (counted as the number of straights); the fifth switchback is the longest, and as you reach its northern end, follow a use trail carefully to an unfenced overlook of the fall. You are staring at Illilouette Fall head-on, and it is beautifully backdropped by Half Dome.

At the junction with the Panorama Trail, turn left (north-northwest) and begin the exposed and hot, but scenic, ascent to Glacier Point. The shade vanished and the views improved following a 1986 fire. Unfortunately, the shade is still absent, but with each passing year, the wall of scrub is higher and only occasionally are the views east still unfettered. The panorama extends northeast to Half Dome, east to Vernal and Nevada Falls, up the Merced River Canyon, and southeast across Illilouette Creek to naked Mount Starr King and sharp-tipped Mount Clark. A few switchbacks climb the final distance to Glacier Point. Once you reach the tangle of trails signaling your imminent arrival at the trailhead, continue first north to the east-facing amphitheater and then make your way west to the parking area (7,185'; 37.72757°N, 119.57439°W). If you’ve never visited Glacier Point, certainly do so now. The short trail to it is on your right (northeast) and the main vista point offers incredible views down into Yosemite Valley.