INFORMATION AND PERMITS: This trip begins in Sierra National Forest and wilderness permits are required. Quotas apply from May to October, with 60% of permits reservable online starting in January each year and 40% available first-come, first-served starting the day before your trip’s start date. See tinyurl.com/sierranfwildernesspermits for more details. Monday–Friday, permits can be picked up at the Bass Lake Ranger District at 57003 Forest Service Road 225, North Fork (559-877-2218), and seven days a week in summer at the Yosemite Sierra Visitors Bureau, located in downtown Oakhurst at 40343 CA 41 (559-658-7588), or the Clover Meadow Ranger Station (559-877-2218, ext. 3136). If you plan to use a stove or have a campfire, you also need a California Campfire Permit, available from a U.S. Forest Service office or online at readyforwildfire.org/permits/campfire-permit.

DRIVING DIRECTIONS: From the CA 49 junction in Oakhurst, drive north on CA 41 for 3.4 miles to a junction with Forest Service Road 222, signposted for Bass Lake. Follow FS 222 east 3.5 miles. Beyond, continue straight for an additional 2.4 miles, but your road is now called Malum Ridge Road (FS 274). Then turn left (north) onto Beasore Road (FS 5S07) and reset your trip odometer to zero. Paved but windy Beasore Road climbs north, passing Chilkoot Campground at 4 miles, followed by a series of dirt roads departing westward. At an odometer reading of 11.6 miles, you reach a four-way intersection at Cold Spring Summit, where Sky Ranch Road (FS 6S10X) departs to the left and a parking area with toilets is on the right. Continuing straight ahead on Beasore Road (FS 5S07), you wind past Beasore Meadows, Jones Store, Mugler Meadow, and Long Meadow. At 20.2 miles, you reach Globe Rock (on your right; toilets) and FS 5S04 which leads left (north) to the Upper Chiquito Lake Trailhead.

Beyond Globe Rock the road surface can be speckled with potholes, although parts are being resurfaced during the summer of 2020. You pass a spur to Upper Chiquito Campground (21.3 miles), the impressive granite domes named the Balls (24.2 miles), the Jackass Lakes Trailhead (26.8 miles), and the Bowler Campground (27.1 miles). Soon thereafter two prominent spur roads bear left, first one to the Norris Trailhead (FS 5S86; 27.5 miles) and just beyond one to the Fernandez and Walton Trailheads (FS 5S05; 27.6 miles). You follow FS 5S05 2.3 miles to its terminus in a large parking area.

If you do not yet have your wilderness permit or need to camp for a night before starting, instead of turning onto FS 5S05, continue along Beasore Road. You pass FS 5S88 (branches south 0.4 mile to Minarets Pack Station; 29.6 miles) and quickly meet the end of paved Minarets Road (FS 4S81; 29.8 miles), which has ascended 52 paved miles north from the community of North Fork. At this junction, you stay left (northeast), turning onto FS 5S30, and drive 1.8 miles to a junction at the Clover Meadow Ranger Station. Here is the small building where you will pick up your wilderness permit. The entrance to the Clover Meadow Campground is just beyond it, a pleasant campground with piped water, vault toilets, and—amazingly—cell reception! There are also vault toilets at the trailhead.

Note: If you are traveling from the south, you may wish to access the trailhead via Minarets Road; use a map app for directions.

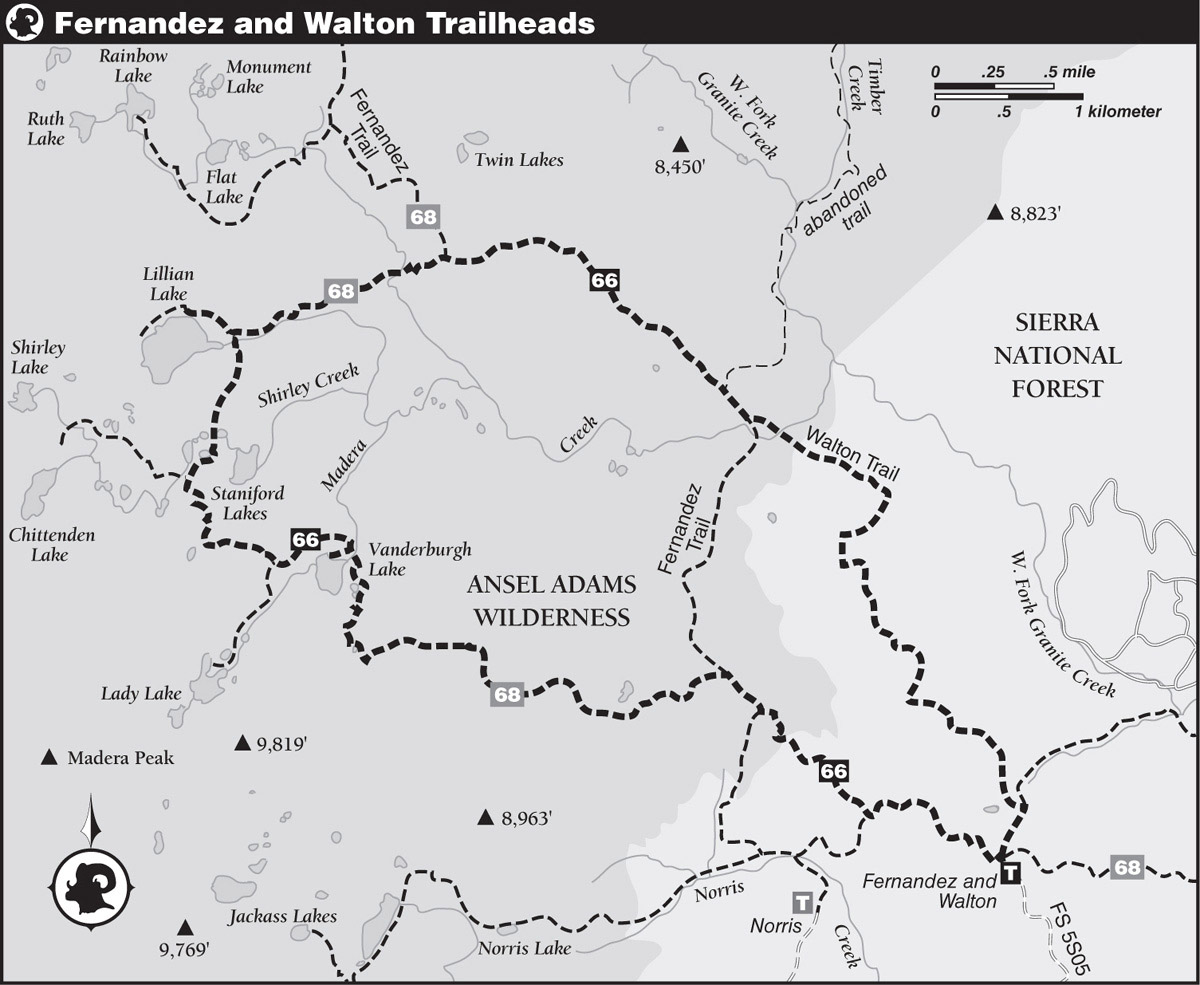

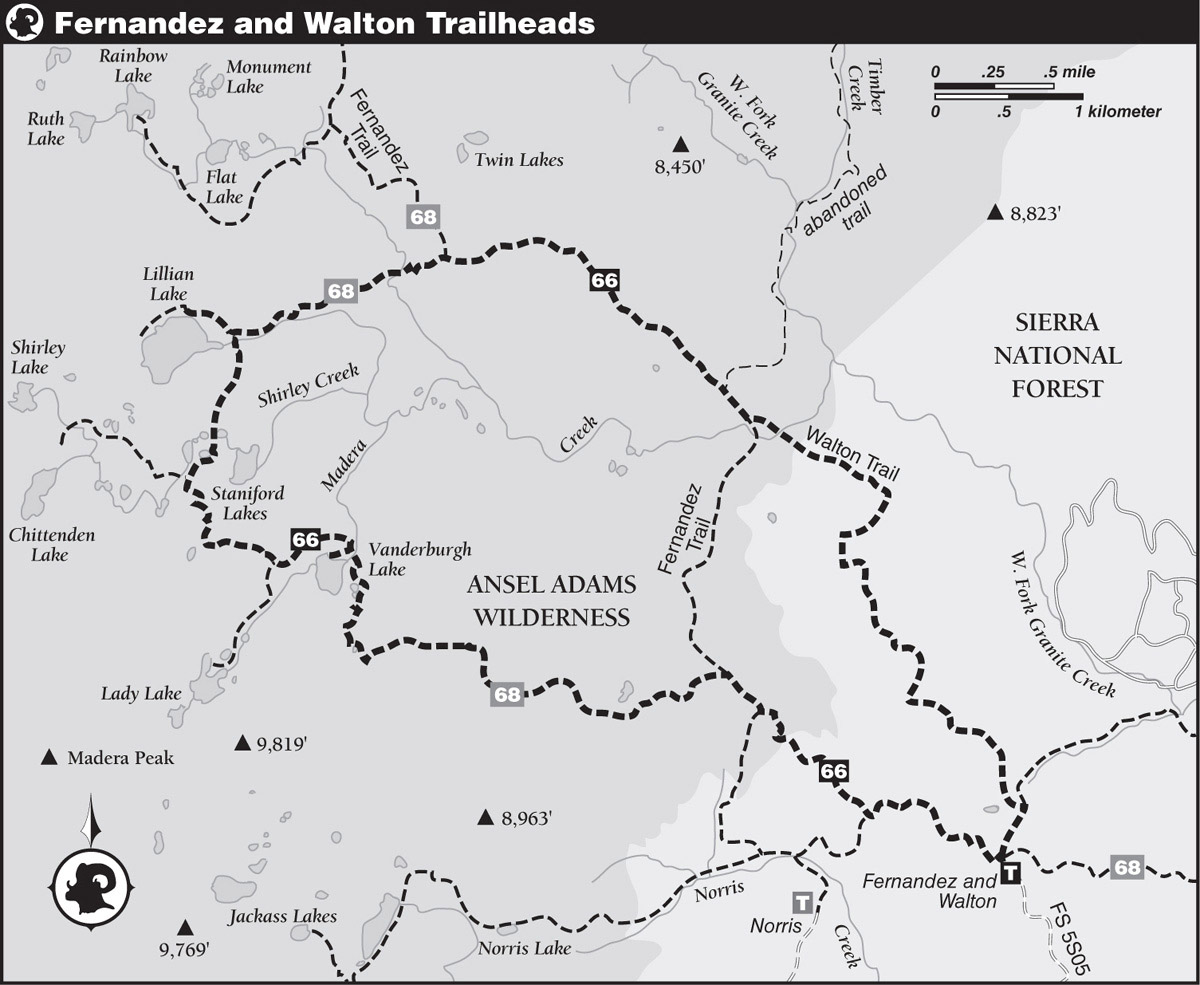

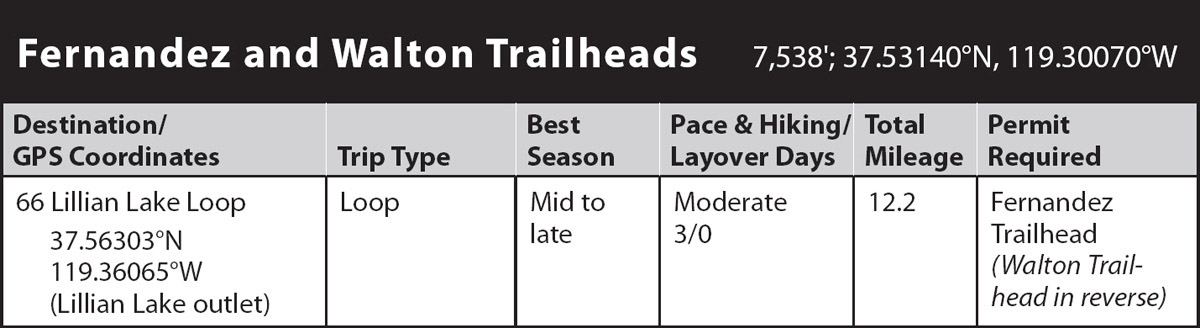

trip 66 Lillian Lake Loop

Trip Data: |

37.56303°N, 119.36065°W (Lillian Lake outlet); 12.2 miles; 3 days |

Topos: |

Timber Knob |

HIGHLIGHTS: Nestled beneath Madera, Gale, and Sing Peaks, just southwest of Yosemite National Park, the many lakes and easy mileage on this trip provide ample opportunity for exploring, fishing, and dayhiking in Ansel Adams Wilderness. The lakes along this loop rival the diversity offered in any Sierran lake basin around the 9,000-foot mark. The 12.2-mile distance includes only the main loop, but budget in hiking an additional 2–5 miles for detours to Lady Lake or Chittenden Lake or to more fully explore Lillian Lake.

HEADS UP! The first and last miles of this hike have been partially burned by the 2020 Creek Fire, but the lake basins remain untouched as this book goes to press.

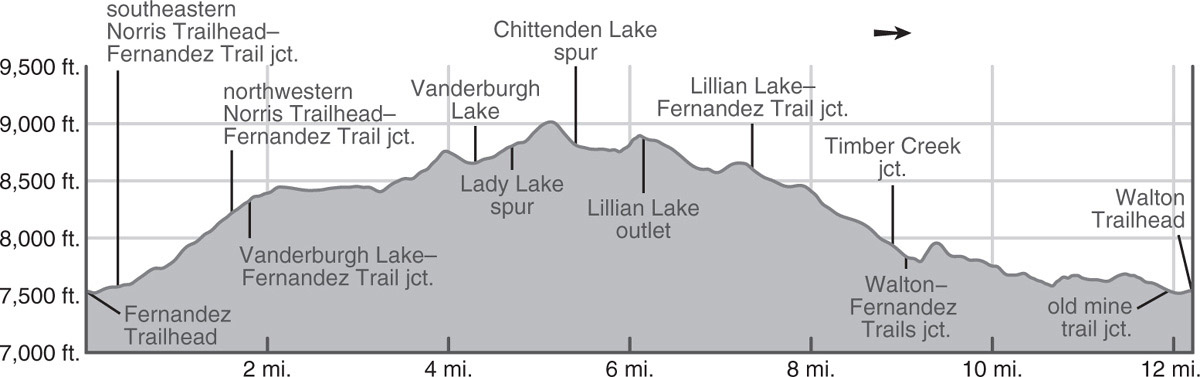

DAY 1 (Fernandez Trailhead to Vanderburgh Lake, 4.3 miles): Two trails depart from the parking area at the end of Forest Service Road 5S05, the Walton Trail and the Fernandez Trail. You will be departing along the Fernandez Trail, located along the western side of the parking area, and returning along the Walton Trail, located at the northern tip of the parking area. Both are signposted with their respective names.

Departing west along the Fernandez Trail, you pass through a typical midelevation Sierran forest: white fir, Jeffrey pine, and lodgepole pine in the flats and draws and scrubby huckleberry oak on open sandy slopes where slabs lie near the surface. A gentle ascent across morainal slopes leads to the lower end of a small meadow, where you reach a junction with an easily missed and little-used trail that branches left (southwest) and meanders 1.2 miles to the Norris Trailhead; here your route bends to the right (northwest). Beyond the junction your trail’s gradient becomes a moderate one and red fir quickly begin to replace white fir. The forest then temporarily yields to brush as you struggle up short, steep gravelly switchbacks below a small, exfoliating dome. The slope becomes steeper yet near where you enter Ansel Adams Wilderness. Merging from the left is a steep trail that also leads to the Norris Trailhead. Again staying right (west), you continue your steady pull up the Fernandez Trail for a few more minutes to a near-crest junction.

Here, find a signed junction with the Lillian Lake Loop: The right (east) fork, the continuing Fernandez Trail, would be the most direct route to Lillian Lake itself, while left (west) leads there via Vanderburgh Lake, the Staniford Lakes, and the many other lakes in the Madera Creek drainage. Your turn left onto the Lillian Lake Loop and enjoy a generally easy 2-mile tread. Conifers shade your way first past a waist-deep pond, on your right, then later past two often-wet, moraine-dammed, flower-filled meadows. Beyond, the trail climbs to a bedrock notch in a granitic crest. Turning around, you enjoy your first views of the San Joaquin drainage, including dark-colored, pyramidal-shaped Mount Goddard, nearly 50 miles southeast in Kings Canyon National Park. On the crest you arc around a stagnant pond and then make a short descent to Madera Creek.

Note that there is much confusion—and probably sloppiness—in the spelling of Vanderburgh Lake in both official and unofficial sources. For years the name was spelled Vandeberg on maps, but the most recent (online) USGS topo maps are using Vanderburgh, matching the spelling of its namesake, Chester M. Vanderburgh, a Fresno-area physician who enjoyed stock trips to the area. From Madera Creek, the trail curves west past good-to-excellent campsites along the lake’s north shore (8,656'; 37.55039°N, 119.35162°W; no campfires), where steep, granitic Peak 9,852, on Madera Peak’s northeast ridge, is reflected in the lake’s placid early-morning waters as you cast for brook or rainbow trout. If you are trying to decide which of the many nearby lakes to camp near, this is the lowest elevation and most forested of the choices, making it more or less appealing based on your predilection.

DAY 2 (Vanderburgh Lake to Lillian Lake, 1.9 miles): This short-but-sweet hiking day gives you a chance to admire the views, discover the lakes, fish, and maybe even bag a peak.

Gale Peak reflected in Lillian Lake’s waters Photo by Elizabeth Wenk

At the west end of Vanderburgh Lake, climb bedrock to the edge of a lodgepole flat that has a junction with a trail to Lady Lake, well worth the easy detour (see sidebar on the facing page). Beyond, the trail crosses a lodgepole flat and then climbs a few hundred feet on fairly open granitic slabs to a ridge. Here you can stop and appreciate the skyline panorama from the Minarets south to the Mount Goddard area. Descending northwest on a moderate-to-steep gradient, you reach an easily missed junction, where a small sign indicates that a left (northwest) turn leads to Chittenden Lake. The junction is soon after the gradient has lessened and where the main trail bends a little to the right (northeast).

Just 0.1 mile past the Chittenden Lake Trail junction, you see a Staniford lake. A waist-deep, grass-lined lakelet, this water body is not the Staniford Lake that attracts attention. Instead, continue a few more steps until you come to a trailside pond atop a broad granitic crest. In this vicinity you can leave the trail and descend southeast briefly cross-country on low-angle slabs to the largest of the Staniford Lakes, lying at 8,708 feet. This large, mostly shallow lake is wonderful for swimming, sometimes warming up to the low 70s in early August. The great bulk of the lake is less than 5 feet deep, with its only deep spot being at a diving area along the west shore. Among the slabs you can find sandy camp spots.

More ponds, still part of the Staniford Lakes cluster, are seen along the northbound Lillian Lake Loop Trail before it dips into a usually dry gully. It then traverses diagonally up along a ridge of glacier-polished slabs with truly outstanding views to the Ritter Range and the entire San Joaquin drainage—your best views yet. You cross the nose of the ridge and then quickly descend to Lillian Lake’s outlet creek. Just beyond is a junction with the spur trail around Lillian Lake’s eastern and northern shores (8,870'; 37.56303°N, 119.36065°W).

Myriad use trails dive into the beautiful, dense hemlock forest ringing Lillian Lake’s northeastern shore. Camping is prohibited within 400 feet of the northeastern shoreline, but if you continue about 0.25 mile to the north, you will encounter a series of well-used-but-splendid sites set sufficiently back from the lake. As the largest and deepest lake you’ll pass along this hike, Lillian Lake is also the coldest, and its large brook and rainbow trout population is attractive to anglers; the rugged crest rising from the lake’s southwestern shore provides an elegant backdrop.

OTHER NEARBY LAKES

Lady Lake: A spur trail takes off south (left) and climbs gently to moderately 0.6 mile to Lady Lake. As you walk along the outlet creek, about halfway to the lake, you will note an unsigned trail departing from the creek. From here, right leads to a large campsite above the north shore of the lake, while left leads to the east-shore moraine that juts into the lake, with an even better campsite. If you miss this cryptic junction, don’t worry because you will most certainly realize when you’ve reached the shore of granite-rimmed, 8,908-foot-high Lady Lake and can follow the shore between the two trail ends. Both campsites are ideal for large groups—this is one of the few subalpine lakes that can accommodate many tents without environmental concerns.

Chittenden Lake: 9,182-foot-high Chittenden Lake, the highest of the lakes in the vicinity, is reached by a 1-mile spur trail. The trail leads west then northwest from the shelf holding the Staniford Lakes. After climbing open slabs, the trail sidles up to the eastern bank of Shirley Creek. Stepping across the creek, the trail turns sharply left (south), continues briefly under forest cover, and then traverses open slabs. Across here there is no indication of a trail—just continue due south, and before long the lake comes into view. If there are more than two backpackers in your group, don’t plan to camp at this lake because flat space is really at a premium. The best site is on the ridge east of the lake, boasting absolutely stunning views. Peakbaggers may choose to continue from Chittenden Lake southwest to the crest—and Yosemite boundary—then follow Sing Peak’s southeastern ridge to its panoramic summit.

DAY 3 (Lillian Lake to Walton Trailhead, 6.0 miles): Lillian Lake is the last of the lakes along this loop, and from its outlet the trail descends a forested mile east to a two-branched creek with easy fords. After a short, stiff climb over a gravelly knoll, the trail descends to a junction on a fairly open slope. Here the Lillian Lake Loop Trail ends and you rejoin the Fernandez Trail, on which you turn right (east, later south); left (northwest) leads to additional lake basins and onward to Fernandez and Post Peak Passes (Trip 68). The forest cover quickly thickens, and the trail enters a dense forest glade situated in a shallow trough. You are next routed back onto a ridgeline, an old moraine. Drier and sandier again, the trail follows the moraine crest to its end before switchbacking to the drainage below. Soon you then reach a junction with the trail up Timber Creek. Though the junction itself is signposted and obvious, the unmaintained trail rapidly deteriorates, helped on its path to oblivion by abundant uncleared tree falls. Staying right (southeast), you continue down beneath forest cover, quickly reaching a junction in a sandy flat, where the Fernandez Trail forks right (southwest) and the Walton Trail leads left (southeast). Given that these two trails lead to the same parking area and both are 3.2 miles in length, it is up to you which you take, though the Walton Trail requires less elevation gain, has more open views, and takes you through all new terrain—hence it is the route described here. Turning left and walking through the open flat, along which there are many camping options, you soon cross Madera Creek. A possible wade under the highest of flows, this crossing becomes a rock hop by midsummer and can dry out in late summer. To your left (north) is an interesting geological feature, a dark plug of olivine basalt, which was once part of the throat of a cinder cone. This dark monument is most obvious if you look north after you climb the few short, steep switchbacks up the open slope to the south.

Enjoy the open views as you cross this slabby slope, with a slightly different vista north to the Yosemite boundary near Post Peak Pass and south to the Silver Divide in the South Fork San Joaquin drainage. Dropping off the bare slabs into open lodgepole forest, the trail trends south, continuing its descending traverse. Stretches of dry lodgepole pine forest are interspersed with wetter glades where red fir dominates and drier rocky knobs where manzanita and huckleberry oak replace the trees. Turning right (southwest), where an old road once led left (east) to the Strawberry Mine, you promptly reach the trailhead.