INTRODUCTION

THIS BOOK deals with what have been called "the magnificent scraps of paper," the woodblock prints of Japan, and with their modern successors, the creative prints, of which more later. The proper name for the traditional prints reveals their meaning: ukiyo-e, "pictures of the passing world"; and the three examples which open this essay, Prints 2, 3, and 4, have been especially chosen to illustrate certain basic aspects of this enchanting art.

First of all, each print appears on a sheet of handmade paper, delightful in itself and resembling the end papers of this book. This paper is coarse and absorbent, composed of thousands of interlocking fibers into which the ink has been impressed. It is resilient, glowing, and vibrant. Its recuperative powers are phenomenal and it lends luster to whatever appears upon it. The beginning of any good Japanese print is the unique paper upon which it is printed.

Each of the first three prints is a sumizuri-e, sumi meaning "black ink," zuri "printed," and e "picture." Ukiyo-e prints began with such pictures, and color was a late innovation, so that to understand Japanese prints, one must first learn to enjoy the sumizuri-e; and it is a fact that most collectors prize first the black-and-white prints of the early days. Wherever possible throughout this book, sumizuri-e have been introduced, for I hold them in special affection, and if I were asked to nominate one print which has taught me most about ukiyo-e, it would probably be Print 9, a near-perfect specimen of sumizuri-e, a poetic recollection of one of the supreme moments in Japanese literature, and an intricate work of art whose grandeur derives from the judicious use of black and white.

Prints 2, 3, and 4 also illustrate the flowing line that characterizes ukiyo-e and forms its chief artistic accomplishment. The line is bold yet poetic, strong yet evocative, heavy black yet glowing with light, and above all a joy to look at as it twists and flows across the paper. This soaring line is the soul of ukiyo-e, and in these first prints one can see how effective it is. The second figure from the left in Print 4 is as attractive a bit of art as will appear in this book; yet it is composed principally of bold, strong lines, without any color. In most examples of ukiyo-e, this line dominates, and unless one appreciates its essential Japanese quality he misses the lesson of Japanese prints.

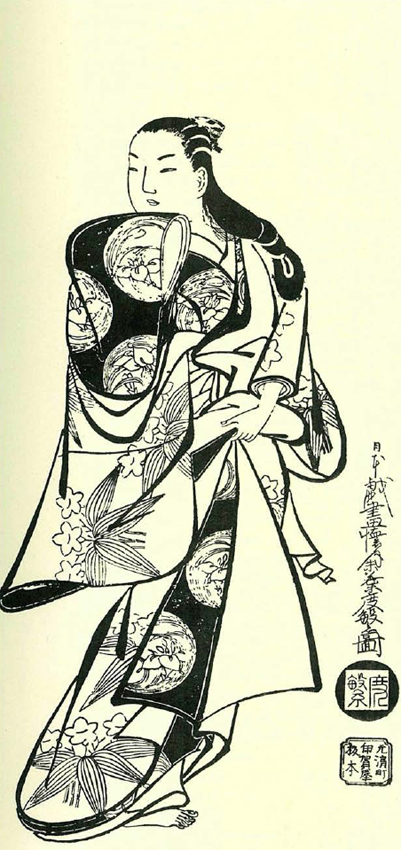

The print on the opposite page is of special interest in that it is the right-hand half of a page from an erotic album; unfortunately, modern publishing standards do not permit reproduction of the left-hand half of the print, which depicts the young courtesan's customer. A great many ukiyo-e prints were frankly erotic in nature-Prints 11 and 13, for example-and others contained esoteric overtones of eroticism that delighted the knowing. Three such different prints as in , 141, and 145-46 have sexual intimations which were not lost upon their original Japanese buyers. For example, the handsome courtesan opposite has her obi tied conspicuously in front, which signifies that she is an inhabitant of the Yoshiwara, the gay quarter of Edo, now called Tokyo. By looking for obi whose big bows ride in front, the reader will be able to spot some of the famous courtesans featured in this book.

Finally, these first three prints remind us of the fact the women who appear in them lived to provide excitement for the rising merchant class that had sprung up in Japan toward the close of the sixteenth century. In the Genroku period, 1688-1703, when ukiyo-e enjoyed its first great flowering, these wealthy merchants were not yet powerful enough to challenge openly the samurai class that ruled the nation; but they had already carved out for themselves a secure place in Japanese life. By law they were required to wear somber clothing dominated by blacks and grays, but the interior linings of their kimono were apt to be of silver and gold. They were forced to live in houses that were outwardly plain, but the inner quarters were often rich in art. The brothels in which they hid their Yoshiwara mistresses were luxurious and the costumes of the girls were resplendent, as Print 160 shows. It is the arriviste world of this rising middle class that ukiyo-e depicted, and in the prints one finds many echoes of that fact. The rowdy, exciting theaters patronized by the merchants occasioned many of the prints reproduced in this book; and it is for this rich record of Edo that the ukiyo-e is today prized by social historians.

3. STYLE OF SUKENOBU: Courtesans in Procession. See note, page 255

Therefore, these first three prints form an appropriate introduction to the art, for without a sound appreciation of sumizuri-e, one's final estimate of ukiyo-e must remain unbalanced; but if one acquires a love of these early prints he can proceed through all the stages of color printing and comprehend what the artist is trying to do, for the basis of ukiyo-e is line, and a print which starts with an evocative line will probably turn out to be a lovely thing, no matter what happens to the colors. I once knew an art dealer who found himself with a stack of faded Japanese prints to peddle, and as each potential customer thumbed them he would chant: "Faded, faded, but as that great collector Frank LloydWright has said, 'All is fled save beauty.'" Actually, it was the poet Arthur Davison Ficke who delivered that line, and although I was always amused when my dealer friend quoted it, trying to lure me into a purchase, I now think favorably of Ficke's statement; when the colors have finally fled we still have the flowing line, and essentially that is what counts.

It seems to me that the chief merit of Japanese prints is their ability to meet the human mind on the simplest level of appreciation and to lure it on, as one's comprehension increases, to successively more complex levels of enjoyment, until the mind is at last brought to contemplate one of the world's more profound problems: What is a work of art?

I now invite the reader to accompany me on a brief reprise of the exciting intellectual journey one undertakes when he first purchases a print. Let us suppose that you have just acquired Print 5, Harunobu's "Girl with Ox," believed to be a portrait of Osen, one of the teahouse beauties of the time, as she sweeps up superfluous love letters. It is easy to believe that this is a work of art. The design is carefully worked out; the coloring is both subtle and appropriate; the total effect is pleasing. If you proceed no further in your investigation than this, you have had a satisfying aesthetic experience, although one of limited scope.

But it is very unlikely that you will be able to stop there. Subtly you are drawn into speculative inquiries that become inevitable, and soon you are asking: "Why is it that Japanese connoisseurs with refined taste refuse to accept woodblock prints as first-class art?" You are now involved in the intricate aesthetic theories of Asia; and no matter how much you originally treasured this Harunobu print, you are forced to confess that it is spiritually on a lower plane than those other works of Asian art which Japanese connoisseurs have generally categorized as first class. For example, it is pretty obvious that prints lack the subtle intellectual content of Asia's famous black-and-white imaginary landscapes. Whether you like it or not, a study of Japanese prints forces you into making value judgments, which is a fine exercise for any mind.

But when you have settled to your own satisfaction the relative position of prints in Asian art, and when you have resignedly come to accept your Harunobu for exactly what it is-no more and no less-you suddenly find yourself asking: "Wouldn't this be a more legitimate work of art if it were a one-copy painting instead of a multicopy print?" This is a most perplexing question, and it has exercised able minds for many years; for when you ask it you are coming perilously close to the heart of aesthetics, and you will never be content until you have penetrated as far into this thrilling field as your mind can take you. For to answer the difficult question of "Can a multicopy print be as legitimate as a one-copy painting?" requires an answer to a much more profound problem: "What is a work of art?" There is no subject matter better suited on which to hang this question than your copy of Harunobu's "Girl with Ox."

You have purchased, for about seven hundred dollars, your original Harunobu, but what, actually, do you have? I should like to analyze rather carefully several possible answers to that question.

First, as we have seen, you have a piece of paper. It is one of the finest papers ever constructed by man. Rembrandt saved all he could find and reserved it for his finest prints. Other European artists also loved it. If you examine it under a microscope, you see a surface consisting of thousands of absorbent fibers casually interlocked in haphazard patterns. As centuries pass, ink that once appeared on the surface fibers seems to sink into the hidden interior fibers, so that from one generation to the next the beauty of the print is deepened and mellowed. Two hundred years from now your Harunobu will be different from what it is now, but it will be no less beautiful. But Harunobu himself had nothing to do with the paper. He did not make it, nor select it from others that were available. He probably never touched it and quite possibly did not even see it. Whatever of art he contributed to this print must have been imparted via some other medium than the paper.

4. STYLE OF MASANOBU: Courtesans in Procession. See note, page 257

Second, you have on the paper some of the most satisfying lines in art. In fact, if from your ownership of this Harunobu you attain only an increased appreciation of line as a component of art, you will have gained the essential lesson of Japanese prints. It is a line that sings, that moves joyously, that evokes empathy, that delights the eye, and no matter how long you own this Harunobu, you will never tire of its gentle, Japanese line. Yet Harunobu himself had nothing to do with the line you see. It is true that he drew a basic sketch for the print, exactly as Giorgione drew a sketch for his "Fête Champêtre" in the Louvre, but there the similarity ends, for when Giorgione's sketch was finished, he went ahead and transferred it onto his canvas; that is to say, Giorgione both drew the sketch and painted the resulting picture. Harunobu did not transfer his sketch onto the wood block from which your print was made; a skilled artisan did that, and often where Harunobu drew thick, he carved thin. Where Harunobu merely suggested an idea, he developed it. In many instances, we suspect that the art-content of a completed wood block depended as much upon the woodcarver as it did upon Harunobu.

Third, your print contains areas of color, skillfully mixed and applied, and the second major lesson which the Japanese print can teach the Western owner is the judicious placement of masses of flat color. But Harunobu neither mixed the colors you see nor applied them to the absorbent paper. That was accomplished by highly trained printers. In fact, Harunobu probably never saw the specific colors that appear on your print. All he did was to obtain from the printer a bundle of key-block proof sheets that looked like the Hokusai key-block proof of Print 6. Picking up one of these proofs, Harunobu indicated the three areas that were to be printed green-panniers, broom, pine needles-but he did not use green ink to do this; he daubed the required areas with an ugly, reddish stain, adding at one corner of the print a swatch of the green he had in mind. This key-block proof was then returned to the woodcarver, who cut the green block. Next Harunobu took another proof and with the same ugly red stain marked the kimono to be printed salmon, and the salmon block was cut. The orange, the reddish brown, and the gray were similarly indicated. When the required color blocks had been cut-in this case, about seven-it was up to the printer to mix the recommended colors, to see that they harmonized, and to apply them to the paper.

By a process of elimination we have now subtracted from your print every tactile component and have proved that Harunobu could not possibly have had anything to do with any one of them. He did not make the paper; he did not cut the lines; he neither mixed nor applied the colors. One further important fact must be borne in mind. At no time in the history of your print did Harunobu ever "paint" it as you see it now. Your print is therefore not a copy of an original work of art, for I must stress that no "original work of art" ever existed, except as a concept in Harunobu's mind. All he did was to set in motion, by means of an idea which he represented in the shorthand of a sketch, the processes which resulted in a work of art. What you have is a scrap of paper to which certain things have been done-but never by Harunobu-and it is interesting that each of the things done to the paper can also be subtracted one by one, for they are tactile accomplishments: the colors can easily be faded out by either sunlight or bleaches; the lines can be removed; and the paper itself can be lifted away strand by strand until mysteriously what was, is suddenly no more.

You are thus driven, whether you like it or not, perilously close to the Platonic concept that your print can be nothing but a constellation of accidental physical components, held together momentarily by their relationship to a master idea. I hold this to be the most logical definition of a Japanese print, and the one that provides the greatest intellectual stimulation.

You are now prepared to face the problem which launched your investigation: "Is a multicopy print in any way inferior to a one-copy painting?" The conclusion you have reached as to what a print is applies equally to a painting, although in the latter case its applicability is not so obvious. One can visit Giorgione's "Fête Champêtre" throughout a lifetime without being forced to consider the conclusions reached above, for one can easily delude himself into believing that, in viewing the canvas upon which Giorgione happened to paint, one somehow or other sees the painting itself, as if the canvas and its accidental pigments were the work of art; but no sensible person can study Harunobu's portrait of Osen without wondering exactly what it is he holds in his hands, for sooner or later he will fall prey to several persistent doubts, which I should now like to express as questions.

Question one: Since Harunobu issued about two hundred copies of his print, what is the relation of my copy to the ultimate work of art which it represents? For example, if you could see at one instant all two hundred copies, would you then understand what Harunobu intended his work of art to be? More practically, how many different copies from among the two hundred must you see before you can detect the artist's basic intention, as for example in the case of Prints 183 and 184?

Question two: Were all two hundred copies of the original printing equal works of art, or was one lucky success the real work of art with the other 199 no better than near misses? And if the latter is the case, how can you be sure that the copy you have is not one of the failures and therefore of no artistic value?

Question three: Is it not more logical to think of a print as an original Platonic idea which has been subdivided mechanically into two hundred equal representations, each a reasonably satisfactory approximation of what the artist intended? Obviously this is the concept upon which the collector or museum has to operate, but to accept the concept as a philosophical principle raises many difficult points, the most perplexing being this: Since it is likely that of the original two hundred prints at least 190 have been destroyed, do the ten surviving now divide among themselves the original reservoir of artistic content, so that each surviving print is now twenty times richer in art-content than it was when issued? Finally, if the day comes when only one copy remains, as seems to be the case with Print 81, does it then absorb the entire art-content with which the original edition was once endowed? You can see that this form of question brings us back once more to where we started: "If you destroy all but one copy of a print, is it then as important a work of art as a painting?"

Question four: Since in the original edition of the Osen portrait Harunobu had nothing directly to do with the paper, the carving, or the printing of his prints, why are they any more legitimate as works of art than a facsimile copy which you could buy in Japan today, hand-carved on Harunobu's type of wood, hand-printed on his type of paper, and colored with his kind of colors? And if you conclude that the copy is an adequate work of art, since it is capable of reminding us what Harunobu intended, why wouldn't a good colored photographic reproduction, like Print 5, serve equally well?

Question five: What is the artistic value of a work like Print 7, which was re-issued in 1916 by printing with certified old paper and old ink from the original wood block preserved since the 1710's? This problem is most perplexing. It should be noted that when the Art Institute of Chicago issued the first volume of its history-making catalogue it saw fit to include as Kiyonobu I, Number 1, a modern printing, like Print 7, whose block dated back to 1698.

In the years when I was assembling the collection shown here, and helping others to assemble theirs, I was extraordinarily busy with other work, yet I think that a day never passed when I did not for recreation contemplate the intellectual problems posed by these alluring scraps of paper. I have reached the following tentative conclusions, but I could be persuaded by some better informed investigator to surrender them tomorrow if he could show me how to escape certain contradictions.

It seems to me that a work of art consists of two parts, and the fact that they are mutually repellent emphasizes the complexity with which we deal. First, a work of art must exist as an idealistic concept in the mind of a human being, but I shall not argue if you prefer to express the condition as "a felt stimulus within the viscera." It is generated from an intuitive impulse which illuminates in an instant the total ultimate possibilities of which this work of art will be capable. This intuitive impulse may be received either before, during, or after conscious thought processes about the work of art have begun, but for most of us it is not responsive to an act of will; that is, the required intuitive impulses cannot be evoked when needed. There appear to be some men who can consciously generate repeated intuitive impulses, and I suppose that this skill is what we refer to as genius. (It is obvious that the entertainment of intuitive impulses is not restricted to artists; an artist is a man who develops his intuitive impulses within the field of the arts; a general develops his in warfare; a scientist, in the field of science.) When the intuitive impulse has been accepted and understood, it is consciously elaborated into a fully developed master idea for the work of art. For example, the grand design is determined; the meaning is reviewed and organized; the techniques which will be effective are selected. When this elaboration is completed a master plan has been evolved and perfected, and it stands ready to be transformed into a canvas, a statue, a poem, or a woodblock print.

When this master plan has been developed intellectually, or viscerally, the first half of the artistic process has been completed, but observe that it exists only as a potential in the mind, or perhaps being, of an individual. It can exist nowhere else, and unless it has once so existed it can never be transformed into an objective realization. That is why it is ridiculous to call a segment of natural landscape a work of art, or a stone that has been accidentally polished by the sea. Such things are adventitiously appealing, because by accident they conform to definitions which human beings have decided to accept as identifying beauty, but the accidents of nature have nothing to do with art.

A work of art must begin as an intuitive insight which has been consciously elaborated into a master idea capable of being objectified; but a work of art cannot be considered created until it has been transformed into an objective realization. When Keats wrote "Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard are sweeter," he was referring only to the first half of the artistic process, for unheard melodies may not be considered art. They are something else. Obviously, Harunobu's intuitive impulse regarding what might be accomplished in a print portraying Osen must have been finer than the master idea which he subsequently developed, and I suppose that in its turn the master idea must have been finer than the end product after it had been filtered through the hands of the papermaker, the woodcarver, and the printer. But in neither of its more perfect ideational forms was it yet a work of art.

5. HARUNOBU: Girl with Ox. See note, page 264

The second requirement of a work of art is its realization in some objective form which the human audience can perceive. The audience is not required to understand the objective form; it is required only to perceive it; customarily, understanding comes later. The general public is always tempted to identify this objective realization of the master idea as the work of art, but as Harunobu's Osen portrait proves, that cannot be the case. The objective realization is best comprehended as a convenient and persisting reminder to the perceptive world that the work of art does exist. It is helpful to keep in mind two characteristics of the objective realization of the work of art. It is not required to conform to what society currently considers beautiful, for a moment's analysis will satisfy anyone that beauty is merely an agreed-upon convention at once arbitrary, capricious, irrelevant, and temporary. I am afraid that beauty as defined by popular taste has very little to do with art. It is closer to fashion. More important, however, is the fact that the technical processes whereby the master idea is transformed into an objective realization are relatively unimportant, and the fact that the Japanese Harunobu in the Osen print utilized-or perhaps commandeered-a certain well-defined set of techniques which he himself helped pioneer does not make it binding upon the Japanese Onchi to use the same techniques when he wants to create his objective realization of Print 242, in which Onchi's radically new techniques proved as successful for his purposes as Harunobu's had done for his. If genius consists of the ability to generate or to entertain repeated intuitive impulses upon which a work of art can be elaborated, then talent is the gift which certain men have for selecting and operating the skills appropriate for transforming their master ideas into satisfactory objective realizations. Consequently, whatever technique proves effective for the job in hand is the right technique. There can be no other hierarchy of values, which disposes of the question: "Is an oil painting more important as a work of art than a woodblock print?"

It is apparent that I have maneuvered myself into a difficult dualism: a work of art is both an idealistic concept, never fully realized, plus an objective realization whose function is to remind the world that he complete work of art exists. It is a dualism which contains many perplexing contradictions, but one with which I have been increasingly content to live. It has enhanced a thousandfold the joy I have found in prints, and it has given me a philosophical base from which to conduct my daily work. Few abstract ideas ever give a man so much.

The questions asked earlier may now be answered. The portrait print of Osen which you bought is an objective realization of a master idea which Harunobu the artist developed from an initial intuitive impulse. The realization was accomplished mainly by skilled artisans working upon Harunobu's rough report of his master idea, delivered in the form of a sketch. The print's function is to remind you that a work of art exists.

If all two hundred copies of the original edition were extant, one would in no way diminish the art-content of another. The two hundred would merely be capable of reminding more people that a work of art exists. It is true, however, that of the two hundred prints in the original edition some were better executed than others and can be said to have been materially closer to what Harunobu intended than those with poor registry or smeared colors. That is why, as we shall see later, an amusing argument has arisen over Print 175. Also, to buy any copy of Print 233 is now risky, because the artist rejected many of his printings as having failed to come up to his demanding standards; but, prudently, he did not destroy the failures; he kept them in the corner and either he or his heirs later peddled them at high prices.

6. HOKUSAI: The Poet Abe no Nakamaro Longing for Home (key-block proof). See note, page 274

Obviously, when only one copy of a famous print remains, its money value is enhanced, but not its art-content. When only one copy exists, as only one copy of the "Fête Champêtre" has always existed, its responsibility to an appreciative world is increased, but not its art-content. In common sense, it is obvious that since Giorgione may be presumed to have touched the canvas of the "Fete" and to have applied the pigments with his own hand, the "Fete" has a certain souvenir value which your print of Osen, which Harunobu probably never saw or touched, cannot have. But souvenir values are not art values, and when Giorgione started work on the actual painting of the "Fete" he surely came no closer to realizing his master idea than did Harunobu and his team of artisans when they produced the Osen portrait. In Giorgione's case all shortcomings could be attributed to one man; in Harunobu's to a team of men. But the relationship of objective realization to master idea must have been about the same. If this concept seems repugnant-and to some it does, for they insist that a canvas actually touched by Giorgione must be finer art than a print not touched by Harunobu-please consider the roomful of Rubens in the Louvre not far from the "Fête Champêtre"; we know that students applied much of the pigment and some of the underlying drawing; so this leaves a Rubens somewhere between a "Fete" and a "Girl with Ox," and pretty soon we are lost in distinctions which become ridiculous.

There is another way to approach this ticklish problem of objective realization. Of all the world's performances of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony no two have ever been identical; they could not be. Nor has any even closely coincided with the master idea evolved by Beethoven, just as his finally developed master idea could not have exhausted the possibilities latent in the initial intuitive insight out of which he built the symphony. The analogy to Harunobu's portrait of Osen is close: an orchestra does for Beethoven's master idea what the woodcarvers and printers did for Harunobu's.

Finally, if all two hundred prints from the original edition of the Osen portrait were destroyed, there would be some merit in having available one of the modern hand-carved, hand-printed facsimiles which you can buy in Japan; its merit would derive from the fact that it was created under almost the same conditions, using almost the same materials as the original. It is therefore slightly closer to the spirit of Harunobu's objective realization of his concept than our color reproduction, Print 5. That is why hand-carved Roman copies of lost Greek statues have a minor artistic value of their own, for they are the only reminders we have of the fact that Greek artists once entertained transcendent intuitions and realized them in majestic form. However, the modern facsimile of the Osen is markedly poorer in evocative power than one of the two hundred original copies issued under Harunobu's direction, but only because cumulative errors must have been introduced in paper, wood, carving, pigment, and printing, and these remove the end product a little farther from what Harunobu originally intended. Since I doubt that Harunobu ever saw or touched the original of Print 5, which now rests in Honolulu, I obviously do not love this print because it was ever close to Harunobu; I love it because it represents in objective form a dazzling idea which Harunobu once entertained. However, later in this essay I do admit that I cherish any print a little more if it once belonged to someone like Edmond de Goncourt, Louis Ledoux, or Frank Lloyd Wright, but when I say this I am speaking as an antiquarian interested in the history of collecting and not as an appreciator of art. The fact that De Goncourt once owned a print is as irrelevant artistically as the fact that Giorgione once touched the "Fête Champêtre."

As to the value of Print 7, which was struck off on old paper using old ink applied to an original block carved more than two hundred years ago, I must confess perplexity. I see some merit in having such a print available, especially when all copies of the original seem to have been lost, which is the case of a handsome Kiyonobu block held in the Freer Gallery, but I would not buy such prints myself; the three I have came with another collection. Yet I know that Japanese ink in its solid form retains its properties for centuries and is truly identical with what it was three hundred years ago; the paper is demonstrably the same, for it also is identical; and the wood block is unquestionably ancient; but it seems to me that enough change must have taken place in the latter two components to produce cumulative variations which remove the resulting print some further distance from what the artist originally intended. On the other hand, I confess that frequently the modern printing has been done so adroitly that I cannot distinguish the copy from the original, nor can many others, which is why honorable publishers fasten onto the backs of their copies certificates explaining how they were printed. Intending counterfeiters do not, and I would not care to estimate the number of undetected copies held presently in unsuspecting collections, including my own. In recent times the carved blocks of both Goyo and Onchi have been used posthumously for large editions; the latter bear certificates admitting late origin; the former do not. I say I am perplexed by this problem because I fear that my objection to such prints stems from antiquarian considerations and not from artistic ones. I am perilously close to saying: "I don't like this Goyo copy, made only shortly after his death by the same printer who made the originals, from the same blocks and using the same paper and ink, mainly because Goyo never touched the print." And that of course is, artistically speaking, nonsense.

It comes down to this. Art concerns only two value judgments: "Was the original master idea of merit? Was it effectively realized?" One is not concerned with whether it was tastefully realized or in conformity with prejudicial standards. On the other hand, it is obvious that it will usually be the dedicated and skilled artist who will have the best chance of either generating a good master idea or of effectively realizing it. This is merely to say that professionals create art, not amateurs.

Japanese prints are a joy to those who know them, for by the processes I have briefly summarized, these magnificent scraps of paper lift us from idle contemplation of what was an unimportant plebeian art into the upper realms of speculation, and anything which can do that is good to have around.

At this point the general reader may wish to pass directly to the prints, for what follows is largely an explanation of how the ukiyo-e which appear in this book were assembled, information that may be of more interest to fellow collectors than to others. I would urge, however, that the reader first glance through those paragraphs below and on page 22 that explain the inclusion of modern prints, to my mind one of the most important features of the book.

7. KAIGETSUDO DOHANI Courtesan. See note, page 255

In 1942, America's foremost collector of Japanese prints, the successful New York businessman and poet Louis V. Ledoux, started publishing "what ultimately became, in five sumptuous volumes, the most handsome catalogue of an ukiyo-e collection ever issued. The work produced two opposite effects, the second of which would have dismayed the author.

On the one hand, it demonstrated to Japan and Europe the high level which American connoisseurship had reached, which was Ledoux's intention. But on the other, it stultified American collecting for a decade, because comments occasioned by it created the impression that this was the last great assembly of Japanese prints that could ever be collected by one man. The international market was supposed to be dried up; Japanese storehouses had no more prints to disgorge; and all previously existing major collections in America had come to permanent rest in museums.

Among the potential collectors who were scared off by the Ledoux catalogue and its attendant rumors was the present author. For some time both my travels and my interests had been concentrating on Japan, and I had often casually considered starting a small personal collection of prints, but I knew, for the experts had told me, that no good ones were available.

Then three unrelated accidents changed my mind. First, while I was exploring in the Afghan desert, a letter arrived advising me that I had unexpectedly inherited from a donor I had not seen in twenty-five years a small, choice collection of Japanese prints. So whether I wanted to or not, I had become a collector.

Second, the trustees of the estate of Charles H. Chandler, of Evanston, Illinois, called upon me to discuss the sale and dispersal of the great Chandler collection, consisting of 4,533 prints assembled mainly in the first two decades of this century, when collecting was at its height. I found to my surprise that there was a possibility that this splendid group, containing many masterpieces, might possibly be sold to a single purchaser.

Third, and as I look back on this fact it seems the most important of all, I discovered the contemporary school of Japanese prints. I grew to know some of the artists and to love their work. From them I acquired many handsome prints that spoke to me in vital, modern accents. I therefore conceived the idea of doing what no one else had done before: building a single, small collection of choice prints that would start with Moronobu and continue right down to the challenging work of today.

When I began collecting seriously I suddenly discovered that many art shops around the world had excellent single prints. In Paris, London, and New York, dealers had surprisingly good, though small, stocks. I also found that Japanese collectors were willing to sell or trade choice items and that small collections were constantly coming on the market.

8. MASANOBU: Onoe Kikugoro. See note, page 257

However, it was obvious from the start that one could not hope to duplicate or even rival the great Ledoux collection; prints of supreme quality are not coming onto the market rapidly enough. But I found that I could do what Ledoux had not done: I could gather into one small collection representative examples of the exquisite work of the past plus the thundering vitality of the present. It was within those limitations that I worked. The present volume, in its quiet and limited way, demonstrates what any collector can accomplish in today's market. It is, I think, the first private collection that exhibits the entire gamut of Japanese prints. If it has any special merit, this lies in the fact that in the later pages I have chosen from the work of living men, men whom I love as creative brothers, for they have produced a group of prints which illuminate our age and form a worthy capstone to the work of the past. The collection here offered is thus not merely an antiquarian thing, preserving and treasuring past beauties; it is an exploration into the future. It has an intellectual justification of its own.

The critical notes appearing at the end of this book are the work of Dr. Richard Lane and indicate where each print was found. Here the reader will quickly discover that of the 257 prints reproduced in this volume, 166 came from the Chandler collection. This could be construed as proving, not that Japanese prints are available today, but that anyone can have a reasonably good collection if he can stumble upon a treasure trove like Chandler's.

That is not a fair conclusion. When I started collecting I knew what the Chandler collection contained: a wealth of Masanobu, Toyonobu, Harunobu, Utamaro, Sharaku, Hokusai, and Hiroshige prints. Therefore I bought few or no prints by these artists, even though thousands were offered.

Similarly, dealers offered me dozens of fine early prints, but again I elected to gamble on acquiring the Chandler holdings. Had there been no Chandler prints in the offing, and had I been restricted only to the prints available in public shops over the past five years, I would nevertheless have been able to build a collection just about as good as the one here offered. It is interesting to note which Chandler prints would have been unobtainable elsewhere: the Choki snow scene, Print 174; the big Kiyomasu, Print 16; and the Toyonobu puppeteers, Print 81. They are unique treasures. The others could have been duplicated, and still can be, not always in identical subject matter, but in prints of the same relative importance.

Take for example the case of the Kaigetsudo prints, like Print 15. After Ledoux accumulated six of these rare masterpieces, it was confidently assumed that this feat could never be duplicated. In fact, it was doubted that any additional Kaigetsudos would ever appear on the market, and collectors like me accepted the prospect of having no prints by these artists. But in 1957 five different Kaigetsudos came up for sale. Two are still available in Japan. Dealers in that country also have for sale three substantial general collections which, if combined, would surpass what is shown here. From California a marvelous collection will one day be available to the general buyer.

Collectors are repeatedly asked to compare their collections with others, and this provides me with an opportunity to point out once again how rich our public collections of ukiyo-e are. The 257 prints shown here have been chosen from a total of about 5,400, of which half are Hiroshiges. The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston owns a total of more than 54,000 marvelous prints. For example, Utamaro once issued a set of six portraits of women against gray grounds, superbly designed and looking much like Print 163, but better. Certainly, they are among Utamaro's masterworks and became quite popular, because later he reissued the series with new titles and minor changes. There are thus twelve different prints in this memorable series, and for the past ten years I have been hoping to find one. None has ever come my way, but Boston has eight excellent copies. It is probable that only a very few of the prints shown here would be needed by Boston to fill holes in its collection. For example, this book has nine Utamaros. Boston has over seven hundred.

A good way to judge any collection is by the number of big sumizuri-e and tan-e prints it has, because these are the ultimate rarities in ukiyo-e. I have managed to acquire four: one tan-e, the Kiyomasu, Print 16; and three sumizuri-e, the Kaigetsudo, Print 15 and the two Kiyomasus, Prints 21 and 23. But the Art Institute in Chicago has a total of thirty-seven, including eight sumizuri-e and twenty-nine tan-e. In general, it has a magnificent collection, as does the Metropolitan in New York.

A cautious assessment of the condition of each print will be found in the notes, but certain of the prints are in such exceptional condition as to merit special notice. The big Masanobu uki-e, Print 43, was kept in a traditional Japanese scroll box, apparently from an early date, and is breath-takingly beautiful. The Buncho portrait of Osen, Print 127, is in handsome condition, while the Kitao Masanobu book on the Yoshiwara, of which Print 141 forms the middle pages, is in an unusually good state of preservation.

Like most collectors, I find much pleasure in identifying prints once owned by illustrious predecessors. For example, the notable Japanese pioneers Wakai and Hayashi once held many of these prints, and their seals are seen, respectively, on Prints 21 and 226; Kobayashi, Kuki, and Mihara are also represented. Most of the distinguished French connoisseurs, who in Europe launched both the love of ukiyo-e and its scholarship are here: Gonse, Manzi, Haviland, Jacquin, Bing, Rouart, Vignier, and Koechlin. The finest German of them all, Straus-Negbaur, is represented in strength; Jaeckel, Von Heymel, and Tikotin also appear, as do Bateson, Kington Baker, and Hillier of England.

Most of the Americans are here, of course, from Fenollosa, the dean of all ukiyo-e collectors, to Happer, Morse, Wright, Chandler, Ficke, Gookin, Field, Ainsworth, Metzgar, Mansfield, Ford, May, Schraubstadter, Ledoux, Grabhorn, Packard, Lane, and the two pioneering collectors of moderns, William Hartnett and Oliver Statler. Present in the collection, but not represented in this book is one extremely distinguished name: De Goncourt, with several fine Harunobus and others. Four distinguished collections are missing, and I regret their absence; Vever, Morrison, Swettenham, and the Spaulding brothers.

The reader will find, running through the collection, recurrent portraits of three famous actors: Sanokawa Ichimatsu, with his mon, or crest, in the form of a stylized Chinese character, well shown in Prints 41 and 44, appears twelve times; Segawa Kikunojo, with his mon of a sheaf-like bale of cotton padding, as seen in Print 27, is shown seven times, always in female roles; while the various Ichikawa Danjuros, with their memorable mon of concentric squares representing nested rice measures, as seen in Print 71, appear eighteen times. These same mon also appear often as decorations, as in Prints 43, 53, and 60, and such thematic repetitions are one of the peculiar pleasures of ukiyo-e.

The reader will also spot for himself the many deliberate cross-references presented in these prints. It is interesting to compare how Masanobu and Kuni-yoshi, many years apart, handled the same incident in Prints 46 and 215; and how Kiyomasu borrowed from himself in Prints 19 and 20.

At present these prints find their home in the Honolulu Academy of Arts, where they may be seen and where I hope they may remain permanently. I am not unmindful of the glowing passage written by De Goncourt, one of the most perceptive comments ever made about collecting: "My wish is that my drawings, my prints, my curios, my books-in a word those things of art which have been the joy of my life-shall not be consigned to the cold tomb of a museum, and subjected to the stupid glance of the careless passer-by; but I require that they shall all be dispersed under the hammer of the auctioneer, so that the pleasure which the acquiring of each one of them has given me shall be given again, in each case, to some inheritor of my own taste."

It was this passage that inspired Louis Ledoux to direct that his fine collection be broadcast upon his death, so that men new to collecting could enjoy what he had once treasured. In fact, Prints 126, 177-78, and 183 appear in this book only because Ledoux shared De Goncourt's view. But I like museums and consider them one of the major adornments of our civilization, and the Academy in Honolulu is one of the best.

I am indebted to many experts for help in preparing this book, but mostly to Richard Lane, who with his meticulous knowledge of Japanese and his love for ukiyo-e seems certain to become America's equivalent of the great German scholar Fritz Rumpf. Dr. Lane is responsible for the captions and the critical notes and has enriched the text at many points. Miss Marion Morse, of the Honolulu Academy of Arts, tracked down the provenance of each print and in consultation with the Academy staff determined its condition. Raymond Sato, also of the Academy, took the photographs, while those genial friends Marvell Hart and Robert P. Griffing kept all moving forward. Tseng Yu-ho, distinguished Chinese artist, expertly checked the colors of the plates.

In Japan three notable experts, Ishizawa Masao and Kondo Ichitaro of the Ueno Museum staff, and Adachi Toyohisa of the printing firm, inspected many of the prints shown here for authenticity and helped me weed out certain fakes whose inclusion would have been embarrassing. I thank them. Finally, I want to express my appreciation of the way in which Ogimi Kaoru and Kuwata Masakazu have designed and laid out this book and the patience with which Meredith Weatherby has edited it, by air mail, across many miles of ocean.

9. MASANOBU: Lady Murasaki. See note, page 257