Section

2:

THE FULL-COLOR PRINTS

THE FLOWERING of ukiyo-e was made possible by the invention and perfection of the kento, "aiming mark." At the lower right-hand corner of the wood block on which the basic design had been cut, the carver cut away the block to leave standing a right-angle stop, each leg being about one inch long. Obviously, if the corner of a sheet of paper to be printed were snugly jammed into that right angle, a rough kind of registry would be assured, and the exquisite color prints that began to be issued in 1765 were so printed.

But a moment's reflection will show that this right angle alone Would not insure general registry. The paper could be snug in that corner but could still slip noticeably in other areas. To correct this, the carver next added, at the bottom edge of his wood block, an additional kento, this time a straight-line stop about an inch long. Now, if the corner of the paper is snug in the angle, and if the bottom edge is secure against the guide line, perfect register throughout the entire length and breadth of the paper is automatically insured. This method is clearly shown in Print 249, where the rough-edged paper was trimmed away smoothly at two points so that it would fit into the kento; so far as I can recall, this is the only print in the collection still showing such kento trimmings, for which reason they have been retained in our reproduction even at the risk of some injustice to the print itself.

To cite but one example of the remarkable effects the kento made possible, Print 141 is probably the most intricately designed work in this book. The paper is oversize and was printed about twenty times, yet the colors were kept in exact registry. And in exhibitionistic prints of a later date more than forty different colors were applied in sequence, yet thanks to the kento, all appeared in perfect registry. The shimmering beauty of the Japanese color print was thus assured.

We do not know who invented the kento. Four rather widely varied persons have been given credit: a fan manufacturer; a bookseller who was trying to force his way into the fan business; the publisher of a street guide who wanted to show routes in yellow; and that genial experimenter Okumura Masanobu. At any rate, by 1764 several technicians in Edo were technically prepared to experiment with the system, and artists were eager to see what could be accomplished with it.

In 1765, Harunobu began issuing prints utilizing up to a dozen different colors, with each in registry, and his work was so instantly appreciated that the further issuance of older-style prints such as hand-colored urushi-e and two-colored benizuri-e was unprofitable. In each of the remaining prints shown in this book the color was applied exclusively by means of wood blocks, except for certain experimental work in the ioso's, where paper blocks and sometimes glass were used instead of wood. Handcoloring was not to be seen again until its occasional use by present-day experimenters.

The prints that appear in this section represent the classic accomplishment of ukiyo-e. These are the subjects that have become most popular throughout the world, and critics have usually felt that upon this body of work will ultimately rest the artistic reputation of ukiyo-e. Certainly, these lovely scraps of paper present a kaleidoscope of color judiciously arranged insofar as the interrelations of color harmonies are concerned; and from these prints the observer can deduce the second and third artistic lessons to be derived from ukiyo-e, the first having been the use of line.

99. KORYUSAI: Young Man with Hawk. Page 266

Japanese prints demonstrate how adroitly the flat space represented by a sheet of paper can be broken up into pleasing patterns. The placement of figures, the allocation of color, the addition of significant details, and the location of the artist's signature are apt to be harmonious, in good aesthetic taste, and pleasing to the eye. In austere, uncomplicated form Prints 101 and 140 are held to be masterpieces of design, each component being exactly in place. For more complicated patterns Prints 114 and 160 show typical Japanese dispositions of space, with some elements of the design off-balance, but all handsomely interrelated. As for the placement of heads within a portrait, it would be difficult to excel the examples provided by Prints 137 and 168. If the prints of this great era of ukiyo-e demonstrate anything, it is that in the design of flat spaces the Japanese woodblock artists were supreme.

The third artistic lesson of ukiyo-e is the artist's skill in using flat masses of color. Those of us brought up in the West have been trained to prize color which modulates form, as in the work of Michelangelo, or expresses plane relationships, as in the paintings of Cezanne. We are apt to forget that there was an earlier use for color: the application of flat areas across a solid design, so distributed as to yield pleasing results and so interrelated as to produce satisfying color harmonies. Duccio and Fra Angelico knew how to use flat areas of color in this manner, but the experiments of the High Renaissance outmoded their technique in favor of modulated colors which suggested the weight of the subjects to which the color was being applied. Today the earlier use of color has again become popular, and there are few art forms in which this style is more easily studied than ukiyo-e; for here flat areas of color are utilized to perfection. Print 173 is a color masterpiece; in more involved style, Print 177-78 shows how effective the use of flat color can be. The color plates of this section have been chosen with special attention to the wide variety of effects that can be achieved by the Japanese method.

The prints of this classical period fall into several distinct forms, and each has its own ingratiating charm. Easily identified are the chuban, "medium size" prints, which are small and almost square, by Harunobu, like Prints 101 and 102. Their restricted size invited the artist to keep his design simple and his use of color harmonious, for if he failed in either respect, his chuban was apt to be a disappointment. Kiyonaga also did a masterful group of chuban, but space could not be found for any of them, his larger prints being so much more effective.

The hashira-e, "pillar picture,'' flourished in this period, and the nine presented here, Prints 116-24, have been chosen from nearly a hundred in order to show different artists at work on representative themes. This is not an art form that I enjoy, but I do admire the adroitness with which artists contrived to fill the exacting dimensions, the example shown on this page being especially poetic.

Most of the artists represented in this classical period designed hoso-e, the short, narrow prints like the three Bunchos, Prints 125-27. Prints 128-29 demonstrate how pairs of hoso-e were sometimes combined to make a diptych, while Prints 133-35 demonstrate their effectiveness in triptych form. Hoso-c are not expensive and inch for inch undoubtedly represent the simplest and most rewarding way of augmenting a collection.

But the characteristic print-format of the classical period was the oban, "large size," and the first two offered in this book, Prints 114-15, are splendid examples. The paper is solid, with a life of its own; it is handsome to see and exciting to touch; it is a much more vital background for a work of art than either canvas or wood, which accounts for the fact that in the greatest prints it was so often left bare to sing its own song. I find the paper of an early oban one of the most lyric materials in art; in later stages of the classical period the paper grows thinner and loses some of its appeal, but in a print like 115 it is a magnificent substance and from its heavy, resilient body both color and line stand forth brilliantly. The oban size is particularly appropriate to the best Japanese papers; it is also of a proportion pleasing to most eyes; and it accommodates itself well to a wide variety of subject matter, being especially well adapted to portraiture. In fact, an oban on fine early paper is about as harmonious an art form as the world has produced; and in this book we are fortunate to be able to present some excellent examples. As in the case of hoso-e, pages have been set aside to demonstrate how effectively two oban unite to form a diptych, Prints 177-78 and 180-81, and how impressive they are when three are strung together in triptych form, Prints 153-55.

In subject matter the classical period continued several established types and developed others of its own, and it is the latter which give it character. For example, the three Bunchos already referred to, Prints 125-27, are in content nothing but an extension of the actor prints popular in the earlier urushi-e period. True, they are refined and the color is expertly block-printed rather than hand-applied, but spiritually the Bunchos are little different from the Kiyomasu II actor prints. Nor is there much change in content of the hashira-e. But in three areas, the classic oban did make significant new contributions. First, the two prints that combine to make the striking diptych of Prints 177-78 seem to me to present an idea of content that is radically different from what one finds in the early period. Six women and a boy, each differentiated and with her own personality, rest in a specific and developed landscape with living trees, atmosphere, and the smell of flowers. This is quite an advance over Print 92; the picture is more complete; the psychological content is more interesting; and the sense of the world is much more impressive.

The second major innovation of the oban in this period was the portrait of a big head that fairly filled the print. It has not yet been ascertained who initiated this striking new manner, but Prints 137-38 were among the earliest, just as the four Sharakus of Prints 167-70 were among the greatest. In the market today the so-called "big heads" command top attention after the Kaigetsudo women.

The third innovation was the portraiture of beautiful professional women, the bijin-e, "beautiful-woman pictures," Prints 183-86 being typical examples, although Prints 162 and 164 are perhaps the more pleasing.

Finally, the prints of this period are marked by two unusual technical experiments. When certain prints, such as 160 and 170, were finished, with all colors in place, a stencil was cut masking everything but the background. To the parts thus left exposed a workman applied, by brush and not by block, a mixture of glue and powdered mica. When dried, the mica ground scintillated with an iridescent quality, and today such prints are unusually attractive to collectors. Such use of mica was known in the early period, but we have come to think of it as one of the marks of the classical period. A second type of background, the vivid yellow seen in Print 182, was achieved by blocks used in the normal manner; such prints are also eagerly sought today, for not many were issued.

But despite the many technical advances in this period, the wealth of variation resulting from earlier experiments was now no more; after Print 98 and until we reach the moderns, all the succeeding prints are nishiki-e, "brocade pictures." All are polychrome prints.

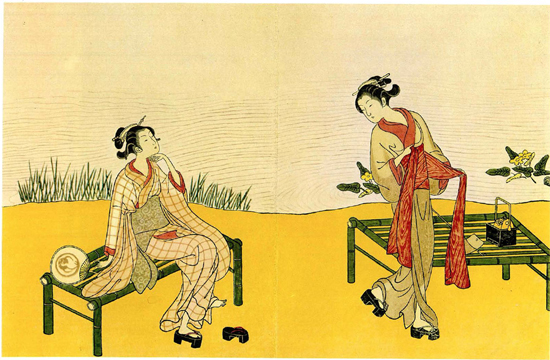

WITH THE prints of Harunobu, that sweet singer of youth and innocence, we enter the full-color period. Study of the frontispiece along with Prints 5, 100, 103-4, and 116 will show what Harunobu was able to accomplish when his printers had perfected their kento marks to permit the use of many different color blocks in succession. The diptych of Prints 103-4 was apparently printed from eight different blocks, including one which caused subtle ripples on the water to be raised in delicate gaufrage, embossing achieved by means of blind printing. Print 5, as we have seen, seems to have utilized about seven different color blocks. From now on there will be no return to earlier styles of print-making, so that Harunobu constitutes one of the great watersheds of the movement. After him, nothing could be the same.

Prints 101, 103-4, and 109 have special charm in that they remind us of one of the most exciting artistic finds of this century. In 1873 a British civil servant named A.M. Litchfield served in the city of Yokohama as crown prosecutor. When it came time for him to return to England, a Japanese admirer gave him as a going-away present a small album into which forty prints of no great apparent value had been pasted. Because the unknown donor had loved the work of Harunobu, all the prints were by that artist and in nearly flawless condition. They were kept in England largely unappreciated for thirty-seven years, by which time a craze for Japanese prints had been generated by exhibitions in Paris, and someone recalled the collection, which was to become famous as the Litchfield Album. It went on sale in 1910, where it was bid in by the London dealer Tregaskis for the sum of $1,500. Today it would unquestionably bring at least $25,000.

Tregaskis broke up the album, soaked off the near-perfect Harunobus, and began quietly to sell them singly at fairly high prices. Whenever one appeared at auction it was labeled "From the Litchfield Album," and this became one of the prized cachets of ukiyo-e history. The present collection has five of the Litchfield prints, and possibly a sixth; they are magnificent specimens of Harunobu at his best.

Print 107, while not in Harunobu's classic style, is important in that it stems from the Hayashi and Straus-Negbaur collections and is apparently the only copy known to critics who wrote on this artist, for it has been widely reproduced. A slightly different version exists, less appealing in execution, and other copies of this are known.

Print 112 presents a fascinating question in attribution. It is signed Harunobu and has always been attributed to him in catalogues and auction lists. The fine artist Shiba Kokan, famous later for his studies in Western art, worked for some years with Harunobu under the name Harushige. Later he confessed that many late Harunobus were actually his forgeries. For various stylistic reasons, both Dr. Lane and I attribute this delightful subject to Shiba Kokan.

Print 113 is not reproduced in color here because it has been done so often before; this must surely be one of the best-known ukiyo-e subjects, and in recent years its notoriety has been increased by the fact that it has become one of the most popular Christmas cards, the subdued coloring being especially attractive in juxtaposition to the snow. Of course, two versions of the print are known, and the variations between them are so substantial-different branches at the top, a black line outlining the snow on the umbrella, and a different obi pattern-that they must have been printed at least in part from different blocks. It is impossible to say which appeared first, but this has not affected adversely the acceptance of either version.

100. HARUNOBU: Girl by Veranda. Page 264

101. HARUNOBU: Shoki Carrying Girl. Page 264

102. HARUNOBU: Princess Nyosan. Page 264

103-4. HARUNOBU: Two Girls by Stream. Page 264

105-6. HARUNOBU: Girl Greeting Lover. Page 264

107. HARUNOBU: The Emperor's Ladies at Backgammon. Page 264

108. HARUNOBU: Lovers Reading Letter. Page 265

109. HARUNOBU: Lovers Reading Letter. Page 265

110. HARUNOBU: Chinese Scholar and Japanese Geisha. Page 265

111. HARUNOBU: Lovers and Plum Tree. Page 265

112. STYLE OF HARUSHIGE: Girts with Snowball. Page 26$

113. HARUNOBU: Lovers in the Snow. Page 265

Koryusai:

FOR THE beginning collector who must budget his funds severely, there is probably no ukiyo-e artist on whom it would be more sensible to specialize than Koryusai. Because he is less popular than either Harunobu, who preceded him, or Kiyonaga, who followed, his prints are usually marked below their real value and offer real bargains to the discerning. But what makes him especially appropriate is the wide range of his types.

His early chuban can sometimes not be distinguished from Harunobu's, and I regret that space precludes the offering of some of his lovely prints in this form. His later chuban are as good as Kiyonaga's, and if one could get together six or eight of these, they would provide a fine understanding of this period.

It has usually been claimed that Koryusai pioneered the fifteen-by-ten-inch oban size, which became standard for ukiyo-e, and some of his works in this dimension, like the two shown here, are superb. In design they are apt to be unhackneyed, and in color, vivid. Their printing is technically excellent, as if the workmen wished to show off their newly acquired skills. But I especially appreciate the balance between the garish colors of the prints, particularly the Koryusai brick-orange, and the heavy texture of the paper. To get a good Koryusai from this middle period is to acquire a print which tells one a great deal about this art. The trail-blazing series of about four dozen prints from which Prints 114 and 115 were taken, First Designs of Model Young Leaves, was started by Koryusai and finished by Kiyonaga; there is always a good chance of picking up some of the earlier prints and they are well worth having. After Koryusai, literally thousands of advertising prints were issued showing famous courtesans attended by their child-servants, but never again did they attain the fresh, startling quality they enjoyed when Koryusai launched the type. The collection contains half a dozen good prints from this series, but lacks the masterpiece: a manservant holding an umbrella over a courtesan while her two girls huddle under their own, which they carry at a different angle. I have never known of a copy's coming onto the market.

The specialist in Koryusai can also obtain fine bird prints of high quality and, above all, the hashira-e which are the special mark of this artist. Print 118 is a good example of his work in this field. Some of the finest hashira-e issued were designed by Koryusai, for he had an aptitude for filling the awkward space presented by a piece of paper twenty-eight by five inches, and each year some of his pillar prints come on the market.

But it is probably a waste of effort to accumulate too many hashira-e. Usually they are not in good condition; by their very nature they were intended to be tacked to pillars, there to accumulate grease, thumb marks, tears, and bleaching. In time even the best are apt to become tedious, but the ones shown here are of interest because of their good condition and general high quality and because they demonstrate how nine different artists adapted themselves to this peculiar strait jacket. Prints 121 and 124 provide two variations on the most popular single theme for hashira-e, and it would not be difficult, in our larger collections, to uncover two or three dozen fine hashira-e depicting this mitate-e, "parody," of the seventh act of Japan's dramatic masterpiece, Chushingura, or The Forty-seven Loyal Ronin. One of the highlights of the play occurs when the geisha Okaru from a balcony reads with her mirror a secret letter held by the hero Yuranosuke, while the villain Kudayu reads the tag end of the letter from his hiding place beneath the porch. Masunobu's and Choki's versions of the scene exemplify the lightheartedness of ukiyo-e, as also do Harunobu's earlier parodies, Prints 108-9.

114. KORYUSAI: The Courtesan Michinoku with Attendants. Page 266

115. KORYUSAI: The Courtesan Michiharu with Attendants. Page 266

116. HARUNOBU: Young Man Playing Kick-ball. Page 265

117. KUNINOBU: Lovers Walking at Night. Page 266

118. KORYUSAI: Girl with Mouse. Page 266

119. TOYOHARU: Lovers with Kite. Page 268

120. SHUNKO: Ichikawa Danjuro V. Page 267

121. MASUNOBU: Chushingura Parody. Page 266

122. KIYONAGA: Maiden Watching a Young Man. Page 268

123. UTAMARO: Agemaki and Sukeroku. Page 270

124. CHOKI: Chushingura Parody. Page 272

Buncho:

IN MANY respects Buncho is the most difficult ukiyo-e artist about whom to formulate a secure artistic evaluation, for in studying him one is constantly faced by anomalies. His reputation is excellent and he is always referred to as a superior artist, but the average collector would find it difficult to list offhand six top-notch Buncho prints. It is an obligatory cliche for sales catalogues to state of any Buncho print: "A fine example of this rare artist"; yet year after year so many of his prints come onto the market that he does not begin to be as rare as men like Shigemasa, Toyoharu, and Yoshinobu, to name only three of his contemporaries. The individual collector usually says, "I was lucky to find this rare Buncho," whereas what would be remarkable would be to collect for any period of time without coming across half a dozen "rare" Bunchos. Further to restrict one's judgment, Buncho's output is extremely limited in form: some delightful fairy-tale chuban, and a good many hoso-e of actors and lovely women. And finally, his style is not easily appreciated; it is angular, harsh, powerfully colored, and rarely completely satisfying.

Yet his reputation remains toward the top of any list, for he is what might be called the artist's artist. The superior quality of his work is instinctively felt, even though when analyzed its various components may not support that first feeling. His prints carry distinction and seem more intellectual than those of either Harunobu, whose chuban excel Buncho's, or Shunsho, whose hoso-e are superficially more appealing. He is a tight, well-disciplined artist and is always fresh in his approach. Collectors grow to love his work, for it speaks to them in much sharper accents than that of other artists more widely known. Yet the myth that his prints are excessively rare, whereas in fact they are fairly common, has kept their price up and many beginning collectors forgo acquiring a Buncho, when actually they would derive more ultimate pleasure from a good example of his work than from the prints they do buy.

Prints 126-27 show the phenomenally popular teahouse waitress Osen, whose fame and beauty preoccupied Edo in the 1770's and whom we jhave met in the Introduction and seen in Print 5. She worked at the Inari Shrine, dedicated to the fox god, located at Kasamori in the outskirts of the city. It was the custom for visitors to the shrine to stop at Osen's teahouse to buy dumplings, and there are many prints of that day showing Osen standing beside the shrine's red torii bearing in her hand a trayful of dumplings, and for some curious reason which I do not understand but to which I am a prey, these prints have always been eagerly sought after by collectors. Perhaps the reader will share with me the suspicion that the girl shown on the kakemono held by the Japanese geisha in Print 110 also depicts the divine waitress.

The most famous portraits of Osen are those by Harunobu, but I have never seen any more exquisite than Print 127, which seems to me an almost perfect print. If we could see Osen, I think she would look something like this.

Print 127 is also of interest in light of my earlier remarks concerning Japanese mastery in using flat masses of color, because the oxidation of time has here given flat color the effect of Western shading. Is this print more interesting because of the oxidation? Is this escape from flat color the reason Japanese connoisseurs especially prize oxidized prints? And note in Prints 145-46 how the blacks representing night have been shaded upwards for more powerful effect. Do Westerners, including myself, particularly praise these because they do, in effect, reject the Japanese system of flat color and pay lip service to our standards of modulated and more plastic color values? These are tantalizing problems, but they serve principally to underline the basic fact: ukiyo-e artists used flat masses of color with maximum effectiveness.

125. BUNCHO: Otani Hiroji III. Page 266

126. BUNCHO: Osen. Page 266

127. BUNCHO: Osen. Page 266

Shunsho Shunko Shun'ei:

THE THREE artists presented here were members of the same school, along with thirty-five others at least, all bearing names beginning with Shun and all to greater or less degree stemming from the influence of Shunsho, a prolific, long-lived, and persuasive teacher. Shunsho's actor prints are one of the highlights of ukiyo-e. For the most part they are hoso-e marked by cluttered backgrounds and a monotony of treatment that would disqualify them from serious consideration except that in spite of their monotony they charm us with a sense of time past. They are distinctive art and taken in large lots remind one of a Bach fugue, playing back and forth upon the same theme yet somehow sending the intellectual content forward. From a large number of Shunsho prints, some in fine condition, I have selected five rather unusual types. The diptych facing shows actors about to do the duck dance and is one of his finest, yet each print taken separately is both typical and satisfying. The early print reproduced in color as Print 130 is unusual both in size and composition and comes to us in such a fine state of preservation as to be useful in reminding us of what ukiyoe looked like when issued. Print 131, facing the color page, is quite the opposite. It is famous historically, having been used in several studies of Shunsho, but its basic colors have faded to the patina so often seen in exposed ukiyo-e. Print 132 is a joyous thing, one of Shunsho's best, but I would rather have included here one of the famous red Danjuros, for they are marvelous prints indeed. But alas I have never found one.

The Shunko triptych, Prints 133-35, is a strange group. In previous instances of its publication these central characters from one of Kabuki's strongest plays have been disposed in various ways, but never as shown here. Originally there may have been two additional prints, and Tomita Kojiro of Boston believes that the print which appeared as item 102 in the Frank Lloyd Wright catalogue of 1927 was intended to stand left of Print 133, while a print now lost must have stood between Prints 134 and 135.

The big heads that appear in Prints 137 and 138 have already been commented upon, but it is important to observe that they appeared rather earlier than we once thought; and the design was not invented by Sharaku.

The placement of the artist Shun'ei in a book like this presents a major problem. Originally I had him far back in this section, just before Sharaku and Toyokuni, where stylistically he belongs, and the reader is invited to see for himself how well this greatly gifted, restrained, and somewhat acidulous artist fits in there. I notice that Ledoux puts him between Sharaku and Toyokuni. But when a group of Japanese experts in this field saw such an arrangement they protested that it gave quite a false impression of Shun'ei; he stands close to Shunko in his big heads and to Shunsho in his fine hoso-e. I am not entirely satisfied with the impression this book now gives; certainly Shun'ei, whom I like increasingly, is later in spirit than Shigemasa, Kitao Masanobu, Toyoharu, and Kiyonaga, and the reader will see that this is true. Apparently he is an artist who fits in nowhere exactly, which is the reputation he has always had. But is there a more distinct, underivative work of art in this book than the hesitant dancer seen in Print 140? Who cares where such a gem is placed in history? It stands as its own self-justification.

128-29. SHUNSHO: Kikunojo and Sangoro. Page 266

130. SHUNSHO: Kojuro, Tsuneyo, and Sojuro. Page 267

131. SHUNSHO: Sukegoro and Nakazo. Page 267

132. SHUNSHO: Nakazo as Hotei. Page 267

133-35. SHUNKO: Sukeroku, Agemaki, and Ikyu. Page 267

136. SHUNKO: Mohuemon, Yamauba, and Kintoki. Page 267

137. SHUNKO: Ichikawa Monnosuke. Page 267

138. SHUN'EI: Ichikawa Ehizo. Page 267

139. SHUN'EI: Ichikawa Ebizo. Page 267

140. SHUN'EI: Nakayama Tomisaburo. Page 267

K. Masanobu Shigemasa Toyoharu:

THE FOUR prints grouped together here are of unusual interest in that each is a typical masterwork of its artist. In 1784, Kitao Masanobu, no relative of the greater artist of this name, who had died in 1764, issued an oversize picture book consisting of seven huge plates in full and intricate color, bound in accordion style. It was a book of stunning impact, frequently termed the most beautiful book of its kind ever issued. As the print opposite shows, it was rather garishly colored; the collection contains two complete copies of the work, the one not shown having the more subdued coloration. A surprising characteristic is the size of the cherry boards from which the prints were printed; there could not have been many such trees in Japan, so that these boards must have been special treasures. The subject matter of the print facing is accurately described by the curious title of the book: Autographs of Famous Beauties of the Greenhouses. The poems which appear attached to the two courtesans thus being introduced were presumably composed by them and written in their handwriting, a delicate Japanese conceit.

Prints 142-43 form one of the most pleasing pairs to appear in this book, for prints showing the industrious little women of Shigemasa are sufficiently rare to merit attention, and they are so designed that almost any two or three, placed together, constitute an attractive frieze. This collection is fortunate in having six of these subjects, two with duplicates showing variations, but it lacks the choicest design of the lot, which can be seen in Ledoux as No. 12. There is something perpetually winning about these Shigemasa studies of women; the designs are simplified and the colors are subdued; great attention is paid to the rendering of fabric and to the precise fall of draperies. But what endears them to me is that within the whole range of classic ukiyo-e, it is only Shigemasa's women that look b'ke Japanese women as the Westerner sees them. For example, Prints 161-62 offer full-length portraits of beautiful women, but I have never seen Japanese women who resemble them; I am afraid they are carefully idealized depictions, taller, slimmer, more ethereal than reality. But if I were to stroll along the banks of the Sumida tonight, nearly two hundred years after Shigemasa worked, and if I reached the geisha quarter, I could see the determined little women from his prints, hurrying along to their night's entertainments. And they would look exactly like the women in Prints 142-43. The world tends to cherish artists who epitomize an age. This is why we accord such praise to men like the Kaigetsudo and Toulouse-Lautrec. That is also why we love Shigemasa and his unpretentious little women. They look like Japan.

Print 144 demonstrates ukiyo-e mastery of European perspective when desired, plus the general up-tilting of rear planes as required by Oriental convention. Here the mixture is applied to a depiction on one contrived landscape of the classic Omi Hakkei, or Eight Views of Lake Biwa. These eight most charming sights in the world were originally identified in tenth-century China by a local painter and applied to scenes of his homeland; six centuries later a scholarly Japanese transferred the subjects to Lake Biwa, near Kyoto. Starting at the extreme upper right and moving counter-clockwise, they are: wild geese descending at Katata; night rain on the Karasaki pine; lingering snow on Mount Hira; evening bell at Mii-dera; autumn moon at Ishiyama; evening glow at the Chinese-style bridge at Seta; returning sails at Yabase; and, almost lost in the center of the print, clear sky at Awazu.

141. MASANOBU (KITAO): Courtesans at Leisure. Page 267

142. SHIGEMASA: TWO Geisha. Page 268

143. SHIGEMASA: Geisha with Maidservant. Page 268

144. TOYOHARU: Eight Views of Lake Biwa. Page 268

Kiyonaga:

IT IS ALWAYS a pleasure to leaf through the prints of Kiyonaga, for no matter what this sweet, reasonable man attempted, he stamped it with his stately concept of human beings moving with dignity against largely static backgrounds. He invests humanity with a grandeur that is good to see, and his men are just as interesting as his women. I would think that in this respect the two unimportant hoso-e Prints 156-57 were almost perfect examples of his art. The three men stand with dignity, their robes falling in heavy, Grecian lines. Their faces are alive but not exceptional. The backgrounds against which they stand are effective but not obtrusive. And the general air of the pictures is one of competence. They form a handsome pair of prints, and although as an admirer of Kiyonaga I had half a dozen more representative prints vying for this space, I preferred these two as an ideal summary of the man. The reader will find that they will live in his memory for a long time, just because they are so unpretentious and right.

Kiyonaga is, par excellence, the artist of the diptych, and in this form he has created nearly a dozen masterpieces. They are so spacious, so filled with light and majesty as to exact praise from almost any viewer. Print 151 is the left half of one of the best and a rare gem even by itself. Prints 147-50 show two of Kiyonaga's good diptychs, the upper one having been selected over several other more famous subjects because it was the only copy known to Hirano Chie when she did her definitive study of Kiyonaga, and therefore may have the accidental merit of uniqueness; and it is interesting that the collection also contains an extra version of the left-hand sheet in different coloring, also the only copy known to Miss Hirano.

Why Kiyonaga should have been so adept in designing diptychs remains a mystery, for other ukiyo-e artists found themselves cramped in this format and preferred the triptych. Possibly Kiyonaga's superb sense of balance and space permitted him to adjust his compositions most easily to the symmetry of a two-sheet format. I have never thought much of his triptychs, for they seem to lack the stately balance of the diptychs, and usually one sheet of the three is either lacking in distinction or unnecessary to the over-all design. The triptych shown here, Prints 153-55, is one of the best, but as always in Kiyonaga's work, the left-hand sheet is a thing by itself and is usually so presented.

As for the diptych that appears in color on the following pages, long before there was any chance that I might one day be its custodian, I wrote: "This is my favorite, a diptych of such subtle yet simple beauty as to epitomize the best of ukiyo-e. . . . There is nothing unusual about the coloring of the kimono except that each subdued color is right for its position. There is no striking design except that the potentially monotonous heads are subtly varied in position so as to produce a satisfying pattern. . . . There is no striking background, only a rough black reaching up to the shoulders and topped by a pale gray. And neither half of this triptych amounts to much when taken alone, for the left is a little crowded, the right a bit empty. But taken together, weighing both mood and technique, this passage of noble human figures constitutes a diptych which makes the frequent comparison of Kiyonaga to the best of Greek sculpture not only reasonable but a way of expressing praise for the Greeks." Today I would phrase this more simply and say: "All in all, this is the most satisfying Japanese print I have ever known." I am delighted to own it temporarily.

145-46. KIYONAGA: Evening Scene at Shinagawa. Page 268

147-48. KIYONAGA: Snowy Morning in the Yoshiwara. Page 269

149-50. KIYONAGA: New Year's Scene at Nihombashi. Page 269

151. KIYONAGA: River Cool at Dusk. Page 269

152. KIYONAGA: Komazo and Monnosuke. Page 269

153-55. KIYONAGA: Sudden Shower at the Mimeguri Shrine. Page 269

156. KIYONAGA: Iwai Hanshiro IV with Manservant Page 269

157. KIYONAGA: Matsumoto Koshiro IV with Geisha. Page 269

Utamaro:

IT IS GENERALLY agreed that ukiyo-e reached its climax in the classic period. Some critics hold that Kiyonaga represented the apex, and the author has shared with many other ukiyo-e students the experience of first underestimating Kiyonaga and then awakening to the fact that he was one of the supreme artists. His proficiency, if not always his psychological warmth, was astonishing, and I would not object if one were to claim that he represented the high-water mark of the Japanese print. What I do object to is exalting Kiyonaga at the expense of Utamaro, for the latter seems to me a very fine artist indeed and I am afraid that those who denigrate his art are blind to its accomplishments. Since the two men were born within a year of each other, I see no reason why one should not conclude that ukiyo-e reached its highest point in the combined work of these two men. It is the good fortune of collectors that many of their lesser works are available at bargain prices-indeed, Kiyonaga's chuban represent one of the real bargains in ukiyo-e-and no collector need deprive himself of a good Kiyonaga and a good Utamaro.

Appropriately, all the prints shown in the following group portray women, for Utamaro excelled in their depiction. And the twelve women shown, plus the little girl, relay to us the charm he constantly saw in the women he so lovingly drew. These are exquisite prints, alluring, delightful, and evocative. I am particularly fond of the two pairs of tall women who face each other, Prints 161-62, even if I said earlier that the figures were too elongated. Print 161 shows two examples of sedate, well-trained women from the upper class-in this series of three he also did the middle-and lower-class types-engaged in the genteel occupations of playing the koto and listening to the chirping of insects; while across the page stands one of the Yoshiwara's leading prostitutes, to whom her kneeling maid presents a cup of tea. It is the Hour of the Snake, nine to eleven in the morning, and the lassitude that pervades this print is skillfully suggested by line, placement, and coloring.

Print 163, of course, has a special responsibility in this collection, for it presents the famous eighteenth-century courtesan Hanaogi, and I have reported elsewhere on my preoccupation with the dozens of prints recording her fame and beauty. This is the only one that has ever been offered to me, and it is, I am afraid, somewhat battered and worn with time, but glowing withal. It was from my account of this haunting woman that I was able to afford most of the prints shown here, so in a very real sense she can be called the patron saint of this collection, except that the word saint is one which hardly applies to this remarkable woman.

Print 164 is an almost perfect Utamaro, for it is not only one of his most handsomely designed and executed prints, but it portrays one of those scenes which the artist so deeply loved: a group of beautiful professional women ready to parade through the Yoshiwara, made up to represent monks from a Buddhist temple.

Prints 165-66 are interesting as demonstrating the high degree of skill attained by the professional woodcarvers and printers at the apex of ukiyo-e production. These two pictures appear on the front and back of a single sheet of nearly translucent paper, but the dual registry is so nearly perfect that no line on one side shows through to betray its existence on the other. Of course, the print would have to be classed as mere exhibitionism except for the fact that it is also a most handsome portrait of one of the popular waitresses of the day and has an artistic merit of its own.

158. UTAMARO: Girl with Glass Pipe. Page 270

159. UTAMARO: Okita Carrying Teacup. Page 270

160. UTAMARO: The Courtesan Wakaume with Maidservant. Page 270

161. UTAMARO: A Maiden of the Upper Classes. Page 270

162. UTAMARO: Courtesan after Bath. Page 270

163. UTAMARO (II?): The Courtesan Hanaogi. Page 270

164. UTAMARO: Festival Trio. Page 270

165-66. UTAMARO: Oliisa, Front and Back. Page 271

Sharaku:

ANYONE who loves prints approaches Sharaku with awe, for his powerful works stand apart in history. They are psychologically profound, spiritually tortured, and mysterious. Issued more than a century and a half ago, they are nevertheless as modern as El Greco, and they are among the most eagerly sought-after prints in all the world.

Their mysteriousness has always impressed me. In the fourth month of 1794 a Japanese Noh actor of whom we know nothing-neither his antecedents, nor his training, nor his personality, nor his subsequent history-came to a publisher in Edo and volunteered to prepare for him a series of prints depicting actors in the popular Kabuki theater, of which he was not only not a part, but to which, as a classic Noh actor, he would normally have been professionally opposed.

In a burst of energy unparalleled in art history, this strange, nebulous man, produced about 145 prints that are known plus perhaps another 45 that have been lost but whose presence can be logically deduced. He issued his sketches in four series: large heads containing dark-mica grounds, like Prints 167-70; large prints containing two full-length actors posed against white-mica grounds, like Print 172; smaller heads on smaller-sized paper with a yellow ground; and hoso-e showing individual actors without mica grounds, like Print 171. His prints were so violent in character that they shocked contemporary Edo and were not a success. A critic at the time wrote: "He drew portraits of actors but exaggerated the truth and his pictures lacked form. Therefore he was not well received and after a year or so he ceased to work."

It is a fact difficult to comprehend that Sharaku issued all his prints within a period of only nine months: at least 190 prints finished within a space of 300 days. Legend says that he left Edo a disappointed man, but today, of course, his works have become prime treasures.

Print 171 is of special interest in that it was once owned by the Danjuro family and was treasured by them, which helps disprove the once-accepted theory that Sharaku was run out of Edo because actors despised his portraits of them. Actually, his portraits seem to have been rather lifelike; it was their psychological probing which doomed them in their day-and made them immortal in ours.

In recent years an unhealthy emphasis has been placed upon buying art as a financial investment, which introduces totally extraneous factors into appreciation. I am glad to report that Japanese prints are poor material for such speculation, as the history of a series of sales of Print 168 testifies:

| Year | Sale | Price | Value of $ | Value of Print |

| 1903 | Bing | $850 | 1.000 | $850 |

| 1911 | Paris | 715 | .917 | 651 |

| 1917 | Hirakawa | 170 | .507 | 85 |

| 1918 | Metzgar | 880 | .454 | 400 |

| 1920 | Ficke | 1050 | .386 | 406 |

| 1921 | Jacquin | 490 | .610 | 299 |

| 1928 | Straus-Negbaur | 600 | .615 | 369 |

| 1935 | Private | 400 | .744 | 297 |

| 1945 | Private | 250 | .563 | 141 |

| 1957 | Japan | 1050 | .327 | 344 |

Investment in almost anything else would have done better, which is consoling. It should caution those who might be thinking of buying prints for irrelevant reasons to leave them for those who appreciate them for their artistic content.

167. SHARAKU: Tanimura Torazo. Page 271

168. SHARAKU: Ichikawa Ebizo. Page 271

169. SHARAKU: Arashi Ryuzo. Page 271

170. SHARAKU: Sawamura Sojuro III. Page 271

171. SHARAKU: Ichikawa Danjuro VI. Page 271

172. SHAEAKU: Oniji and Omezo. Page 271

Choki:

CHOKI is remarkable in that he designed only a limited number of prints, but all with great distinction, and the three shown here comprise one of the highlights of the collection. Of Choki's output, I prefer the mysterious moonlit landscape with two women smoking pipes, which is handsomely reproduced in color in Ledoux, No. 29. It is now in the collection of the Chicago Art Institute and can be seen there. This has always seemed to me one of the perfect prints.

In all that he does, Choki exhibits delicate judgment. His drawing is elfin; his color harmonies are exquisite; his figures are pinched together at the shoulders in Modigliani-style; and his backgrounds are apt to be stunning. He was a fine artist gifted with a personal vision that dominates his prints. After even a brief acquaintance with his work, it is impossible to attribute his prints to anyone else. Besides the pinched shoulders, his artistic signature includes a woman whose draperies fall in a severely straight line down one margin of the print, as exemplified in Print 173, and to a lesser degree in Print 175. But an even better touchstone is an ineffable quality which is not easily analyzed. One feels instinctively: "Only Choki could have done this print."

Print 174, one of his greatest, falls somewhat outside his general pattern, except for the pinched shoulders of the woman, and in unsigned versions has sometimes been accorded to Utamaro. The signed copy shown here was one of the highlights of the Straus-Negbaur collection in Germany, but critics suggest that the red of the old man's robe must have been touched up by newly-cut blocks sometime in the late nineteenth century, a process at which Japanese dealers proved most skillful and which is technically known as revamping.

Print 175 has always been the subject of argument, feud, and delightful discussion among experts and owners, and a full-length essay could be written about this copy and another which always competed with it. Briefly, the story is this: In Paris in the early years of this century two distinguished and competing collectors, Louis Gonse and Raymond Koechlin, both owned copies of this rare and beautiful print. Koechlin's copy, marred by a cigarette burn in the face of the woman, went ultimately to Ledoux. Gonse's copy was sold for one of the highest prices ever paid for a single sheet to Chandler, whereupon Ledoux stated that he had never liked the Gonse copy, while Chandler let it be known that he did not particularly care for the cigarette-scarred Koechlin version. In time the Koechlin-Ledoux copy passed into the hands of the Art Institute, Chicago, whose curators naturally sustained Ledoux's preferences, while the Gonsc-Chandler copy came to me, and 1 hope that I may be excused for having adopted the Chandler attitude. But it is important to remember that when Louis Gonse sold the copy shown here, his friend Raymond Koechlin himself sponsored Charles Vignier's catalogue, which contained this expert appraisal of the Gonse print: "A faultless proof of this sumptuous and rare print." Edwin Grabhorn, of San Francisco, owns a third copy, which came from the Morse collection and which has remained outside the amicable Koechlin-Ledoux-Chicago versus Gonse-Chandler-Honolulu feud.

173. CHOKI: The Courtesan Tsukasa-dayu. Page 272

174. CHOKI: Girl in Snow. Page 272

175. CHOKI: Firefly-catching. Page 272

Shuncho:

ONE OF the finest prints in this book is the diptych which appears in color as Prints 177-78. It is Shuncho's masterwork and in the case of this example has a distinguished history, but it has always created argument because it has sometimes been put together reverse to the way shown here; and there are many who remain convinced that these are but two sheets of a triptych, the extreme right-hand sheet having vanished. Various facts are cited to support this belief: (1) since the signature of the right-hand sheet is in the center, symmetry would require a third sheet to balance it; (2) the woman with the pipe is obviously looking off toward friends; (3) the bench would fit the picture better if it were continued; (4) there is something odd about the relationship of the various parts of the tree.

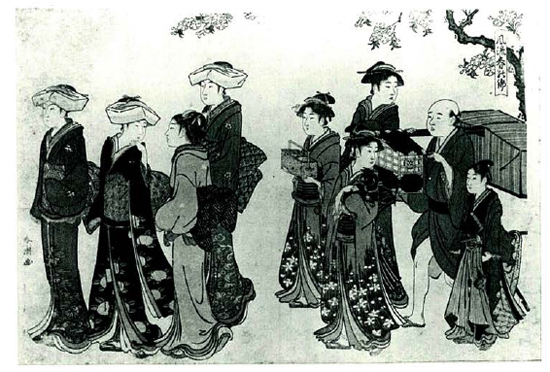

One of the most enchanting little prints in the collection appears below. The gap down its middle makes it look like an uncut diptych, but the fact that it is all in one piece on a standard-size sheet, with signature at one edge and title at the other, would suggest it was meant to be folded, perhaps in an album. A moment's study of this print will show that insofar as the tree and the backward-looking woman are concerned, these are Shuncho trademarks. And a glimpse at the powerful, awkward diptych Prints 180-81, here joined together for the first time, proves further that the angular design and the odd placement of signatures were Shuncho characteristics. This diptych also exhibits once more the backward-looking women. So it may well be that the conjectured third panel to accompany Prints 177-78 never existed.

Print 179 is interesting in that it was the work of two artists. Shuncho did the women in his accepted style; Shun'ei did the men in his. There were many such collaborations in ukiyo-e and the resulting prints were sometimes very fine. This is not one of the best, but these two artists did another in what may have been the same series in which two unusually graceful Shuncho women stand with one fine Shun'ei man, probably the actor Danjuro V, and since the design is less crowded, the result is more pleasing.

Shuncho is a continually fascinating artist. Trained by Shunsho, he broke away from that artist's confining style, but quickly fell under the influence of Kiyonaga, of whom he often seems a flagrant copyist. Yet in his finest pieces, he shows strong draftsmanship and a rugged, inarticulate design which anyone acquainted with his work grows to appreciate.

176. SHUNCHO: Picnic Procession Page 272

177-78. SHUNCHO: Women by Summer Stream. Page 272

179. SHUNCHO and SHUN'EI: Street Scene. Page 272

180-81. SHUNCHO: Riverside Scene. Page 272

THESE six delightful prints are good ones with which to end this classical period of the full-color print. Each is attractive, feminine, highly stylized, and subdued in both color and effect. The yellow ground of the print opposite is not garish, and the mica grounds of Prints 183-86 add to the subjects the touch of luxury they deserve.

Prints 183-84, which show the courtesan Misayama preparing to retire, are famous in ukiyo-e circles in that they have been the subject of much argument. The left-hand print, from the Ledoux collection, shows what is presumed to be the original issue, with flaked mica above a brown background, with a harsh line cutting the background into two parts. This subject has always been a favorite with collectors, and when Ledoux owned this copy he said of it: "This impression of one of the great masterpieces among Japanese prints is in wretched condition-like Komachi at the end of her career. It is worn, faded, repaired and the original luster of the upper part of the ground is gone. It remains, however, a thing of such elegance and beauty that it outranks many a subject in excellent condition and one turns from it always with regret, turns to it always with recognition of its supremacy."

The right-hand print appears to have been issued sometime later than the original brown version and probably from different blocks. Where the first version had translucent mica above brown, this has mica mixed with white. This famous copy was owned by Hayashi, whose seal is seen lower left, but went from Paris back to Japan, where it was widely exhibited and where 1 finally found it, matching it with the earlier version. The arguments of which I spoke concern the authenticity of Print 184. All surviving copies are in suspiciously good condition; but the print is a glorious thing, and if it is indeed a modern forgery, it is nevertheless a masterpiece in its own right.

There is presumed to have been a third state of this print-since such third states exist of the other two prints in the series-in which the harsh line between the two parts of the background was eliminated, leaving only a handsome pale-brown ground covered with shimmering mica. Artistically, this third state must have been particularly handsome on the print shown here, because when seen on the other two it is most effective, but apparently none has survived. There seems also to have been a fourth state, lacking mica, signature, and publisher's mark; it was probably run off to sell at reduced rates.

As prints, these portraits of Misayama on her way to bed are unforgettable. I find them awkward, off-balance, and curiously colored. But I suspect that this is pretty much the way a courtesan looked at the end of the night, with her butterfly hair-do and wearing the costly garments which her owner forced upon her so that she would remain perpetually in his debt.

The Eisho big heads are merely two, and not by any means the best, of a distinguished series issued by this artist. Any print from this set is worth having and some are almost the equal of the best that Utamaro did in this style, but they are difficult to find in good condition.

The Shucho big head, Print 187, is interesting in that prints by this attractive artist often appear without signature, and Dr. Lane has suggested that the publisher was responsible for this, hoping to fob off as original Utamaros work by this lesser-known man. There are several handsome Shuchos extant, and the best contain an animal or a bird held in the hands of an attractive woman. The one shown here is among the finest.

182. EISHI: The Doll Festival. Page 273

183. EISHI: Courtesan Preparing for Bed. Page 273

184. EISHI: Courtesan Preparing for Bed. Page 273

185. EISHO: The Courtesan Shinowara. Page 273

186. EISHO: The Courtesan Someyama. Page 273

187. SHUCHO: Girl with White Mouse. Page 273