Section

3:

LANDSCAPE AND FIGURE PRINTS

REGARDLESS of how one defines the rise and fall of ukiyo-e, pinpointing the apex at Kiyonaga or at Utamaro, any acceptable theory must take into account the belated flowering of the two landscape artists Hokusai and Hiroshige, and the following pages present some of their finest works. It is erroneous to think that these two great masters, who have been so loved in the Western world, invented Japanese woodblock landscapes, for the art had an ancient beginning and an honorable life long before these two men issued their famous series.

Moronobu Print 12 shows how landscape was used sparingly and with fine effect in the earliest prints; while Kiyomasu Print 18 makes a lilting poem out of the formalized waterfall background. Masanobu frequently used similar landscape effects to good purpose, as in his evocation of Lady Murasaki, author of the Tale of Genji, Print 9, and I find such works most pleasing.

One of the first artists to use landscape as a major component of a print, with the human figures subordinated, was Shigenaga, whose Print 61 is a good example of this early, highly symbolized style. Kiyomasu and Masanobu also issued prints in this manner, and they provide tender little glimpses of an idealized nature, similar in effect to the landscapes being done in Italy at the time of Lorenzetti. For an example of this type of landscape art at its most ineffective, see Kiyohiro Prints 89-91, where there is much formalism and little charm.

With Kiyonaga, landscape attains an important role in a series of superlative prints, 149-50 being typical. I have always thought that the diptych of which Print 151 forms a part had a Vermeer quality; but the triptych Prints 153-55 shows our first example of what is to become, with Hokusai and Hiroshige, almost the touchstone of ukiyo-e landscape art. The human beings are kept small in size and toward the front of the picture. The landscape is conventionalized, both as to form and color, in this case with rain represented by carefully drawn parallel lines, another hallmark of the Japanese print. The gods aloft are atypical, but the wind that ruffles dresses but not trees is often seen. It is difficult to believe that the people under the gate who are repairing damage caused by the rain are really wet, but the landscape as a whole is highly satisfactory.

Shuncho's masterpiece, offered in full color in Prints 177-78, seems to me to be landscape of a different sort. It is imaginary in color and form, the fine yellows forming a conventionalized background for the human figures. The tree branches are formalized and the flowers on the far bank are much too large, but this is a dream landscape and objects are not required to appear in proper color or proportion. Nevertheless, these two prints form one of the finest landscape pairs in ukiyo-e, and the eye never tires of seeing these stately women in their imaginary world.

It was from such a formalized heritage that Hokusai sprang with his startling visions of contemporary Japan, and it was his landscape prints that helped awaken French impressionists to problems of color, the rendering of atmosphere, and the organization of a landscape painting. But it seems to me that if one looks carefully at the Hokusais shown here, they are as formal in manner as their predecessors, as arbitrary in coloring, and as idealized in subject matter. I want to stress this lest anyone think, erroneously, that in some mysterious way Hokusai sprang to birth full-blooded without having had numerous predecessors. But having made the point, I must hasten to express my keen delight in these poetic, evocative landscapes of the mind. They are really one of the most impressive accomplishments in ukiyo-e. They are static, unreal, monumental, and contrived; but they sing of nature.

The eight works by followers of Hokusai, Prints 197-204, illustrate how this formalism degenerated into merely reporting the patterns of nature, but several of the prints are minor masterpieces of design and are widely treasured as such.

With the advent of Hiroshige, landscape prints of quite a different type appeared, for Hiroshige, a hard-drinking, roistering man, loved nature. He studied her moods, reveled in storms, sang with birds, sketched the effect of night shadows upon a scene, and spent a lifetime reporting what he saw. He designed a prodigious number of prints, one every other day for thirty-three years, and in them he showed the world a different vision of nature from that which Hokusai had created. His best prints are spontaneous rather than formal. They smell of the earth rather than of the mind. There is humor in them rather than austere impressions. And there is constant evidence of a personal affection for nature.

Eventually each collector of ukiyo-e finds himself comparing the two leading landscape masters, and I have come to think of Hokusai's vision of nature as epic, of Hiroshige's as lyric. One of the best ways to get at the differences between the two is to compare their bird-and-flower prints. Two of Hokusai's are shown, Prints 188 and 193, and they are characterized by careful architectural design, bold use of color to achieve effect rather than to report on the actualities of nature, heaviness in handling, and marked ineptness in drawing birds or butterflies. Nature is seen in a hard, harsh, brightly-lighted reality. Yet the resulting pictures are striking; as art they are fine; it is only as nature that they are inadequate.

Now compare the three Hiroshige Prints 226-28, and one finds that the selection of color is appropriate to the aspect of nature being shown, the birds are lively creatures, there is great movement in each print, and the observation of nature is both keen and accurate. Over each subject there is diffused a tender, but not sticky, romanticism, and it is obvious that the man who created these three prints actually loved nature and with a certain joy reported what he saw. Not one of the Hiroshiges is as fine a print as Hokusai's masterful arrangement in blue; but any one of them is more lyric and honest in its reflection of nature.

The more one studies ukiyo-e landscapes, the more he becomes convinced that these Japanese works must not be compared to those created in the West. Hokusai and Hiroshige did not see nature in the way that Lorraine, Turner, Constable, and Cezanne saw it. The Japanese artists entertained a special vision, and from it built a major contribution to world art. It derives from Chinese and Japanese antecedents and cannot be confused with any other. That was one of the reasons why ukiyo-e landscapes were able to speak so strongly to men like Van Gogh, Degas, and Manet; their shock value was undiminished, and remains so today. One of the reasons why I like Japanese landscape prints so much is that they show me a world which by myself I would never have discovered. From Hokusai I learn the monumental grandeur of nature and the way in which various components combine to form architectural designs of lasting beauty. Under his guidance, the majesty of nature becomes an intellectual thing to be appreciated, studied, comprehended, and filed in memory. From Hiroshige I learn the poetic gentleness of rain, and mist, and snow, and evening, and birds across the moon. I see for the first time the effects of atmosphere upon different natural settings and I catch something of the harmony of everyday life. Particularly, since I have always loved birds and in my own way have studied them since childhood, I am grateful to Hiroshige for capturing the deft, winging quality of birds. In this he is incomparable. It is for such reasons that men in all parts of the world have grown to like Japanese landscape prints.

The second major type of print appearing in this section is the full-length figure standing against a solid background, and this art form is so impressive that I have given all of the Toyokuni pages, Prints 205-11, to this type alone, even though this master was one of the most versatile in ukiyo-e history. In no sense did Toyokuni invent this form, for solitary figures of great power have always flourished in ukiyo-e. Starting with the Kaigetsudo Print 15 and continuing with the Kiyomasu actor, Print 16, these striking creations have served as the symbol of the art. Both Masanobu and Toyonobu created masterful works in this form, several of which are reproduced in this book. In smaller size, as in Kiyonobu's dramatic figure, Print 31, the tradition continued until in the work of Shunsho and Shunko the hoso-e actor print with a simplified background became standard.

But starting with Shunei, Prints 139-40, a new type evolved showing human figures standing against solid-color backgrounds, and these are powerful prints. The Eishi Print 183 is in this tradition, as are certain Kiyonagas, but the form reaches its apex with the works of Toyokuni. The prints shown here are masterpieces of the type and their appeal is instantaneous. This stems partly from the fact that one instinctively feels them to be a culmination of an art form that started back at the beginnings of ukiyo-e, and one can see in the Toyokunis an honored inheritance; but it stems also from the controlled dramatic power of these stately figures. They do not gesticulate unnecessarily, nor do they engage in heroics. They simply stand, coiled and tensed, like ominous forces poised against impersonal, timeless backgrounds. They evoke a very powerful sense of awe and are art of high quality. The skill with which these figures are posed, the appropriate use of subdued color, and the effective utilization of drapery combine to make these figure prints a major achievement of ukiyo-e.

With these stately figures, and with the landscapes of Hiroshige, the great period of traditional ukiyo-e ends. Technically, the art had developed its ultimate resources. In the graphic art of no other country was it possible to print the intricate lines shown in the hair-do of the girl in Print 187. The subtle gradations utilized with such striking effect in Hiroshige's "Sudden Rain at Ohashi," Print 221, represented the ultimate in ukiyo-e techniques.

In the dying days of the art, yellow backgrounds enjoyed a brief popularity, then mica grounds, then solitary figures against bleak backdrops, but finally the various vogues spent themselves and a poverty of invention provided no new ones. Without new styles to tempt the public taste, the market for prints diminished. Then from the West came the box camera and the newspaper engraving, and the destruction of ukiyo-e was completed. By the 1880's the art was apparently moribund.

Of course, as it fell toward desuetude, along with the major artists we have been discussing there flourished the usual group of minor men, and in this particular period they were artists capable of beautiful work. If one were to collect the best big heads of the period, such as Prints 212-14, and the finest landscapes of the minor men, such as Prints 216-17, he would have a respectable body of art. In fact, any collector who applied himself to these artists should in time be able to compile a group of prints that would help us all to appreciate better the causes of the decline of ukiyo-e, but such work has not yet been done.

Hokusai: and Followers:

FROM THE wealth of Hokusai prints available, it is difficult to select nine that do justice to this powerful old man. Obviously, one ought to represent the major series, but this cannot be done in brief space, so let me point out what series and types of prints have had to be eliminated.

The Waterfall series is missing, primarily because its prints are vertical in form and thus cannot be used facing the typical horizontal landscape. This is a most handsome series and one that I especially like, but it has been reproduced many times, and its absence here is not grievous. The Hundred Poems Explained by the Nurse is absent, and this is a loss, because even though I do not appreciate the typical beauty of this series, the prints do represent both Hokusai's capacity as a humorist and the type of work he was doing in the last years of his life. However, it did not seem to me worth while to devote a full page to this amusing, silly series, enchanting though some of its prints are. I do regret very much the absence of Hokusai's horror series, in which ghosts and snakes are featured, for this is powerful art, executed in some of the finest printing and coloring to be seen in Hokusai; but I have never come upon a print from this series in good condition. Also missing, although they were available, are his great surimono (special prints for New Year's gifts) and the best sheets from his second series on Chushingura. It was difficult to eliminate his famous study of cranes, his fan prints, and what is reputed to be the last print he made, his oversize study of surveyors using European transits to lay out a road; somehow this awkward and unlovely print summarizes Hokusai's questing spirit and would not have been out of place.

Now a word as to how certain of the prints shown here were selected, for Hokusai holds a special place in my affection, and I carry the memory of his prints in my mind wherever I go. Obviously, the print that appears opposite is a happy combination of design and color and probably the masterpiece of this series of small-sized bird-and-flower prints.

Two prints were chosen from his best-known series, Thirty-six Views of Fuji, to allow the reader to compare Hokusai's concept of trees along a road with Hiroshige's version of the same subject, as seen in Print 220.

The pair of prints that face each other as 191 and 192 form one of the most handsome spreads in this book. The former comes from Hokusai's imaginary studies of the Ryukyus. It seems highly doubtful that he ever got to Okinawa, but his prints depicting the Chinese-type life and architecture there are among his most poetic. Print 192 is, of course, a glowing classic and comes from a series which contains others equally fine. Even when one recalls the greatest of Hiroshige's snow scenes, this Hokusai remains majestic in the eye.

Two prints were also chosen from his greatest series, the Imagery of the Poets, and the Li Po gazing at the waterfall was printed in color in order to point out certain perplexing problems relating to this print. If one studies the present version minutely and with the aid of a magnifying glass, he will find that it differs in slight details from the version also printed in color in Ledoux. The version shown here is identical with those contained in two major American collections, but if I remember correctly, the Ledoux version is also duplicated in other collections. One is therefore tempted to conclude either that this magnificent series was at one time skillfully forged (we know that there were many incompetent forgeries), or that enough copies were originally struck off so as to require a slight recutting of the key block.

188. HOKUSAI: Bullfinch and Drooping-cherry. Page 274

189. HOKUSAI: Fuji from Kajikazawa. Page 274

190. HOKUSAI: Fuji from Hodogaya. Page 274

191. HOKUSAI: Ryukyu Seascape. Page 274

192. HOKOSAI: The Bridge of Boats at Sano. Page 274

193. HOKUSAI: Butterfly and Tree-peony. Page 274

194. HOKUSAI: Winter Landscape by the Sumida River. Page 274

195. HOKUSAI: The Poet Li Po Admiring a Waterfall. Page 274

196. HOKUSAI: Traveler in the Snow. Page 274

197. HOKUJU: Monkey Bridge. Page 275

198. GAKUTEI: Squall at Tempozan. Page 275

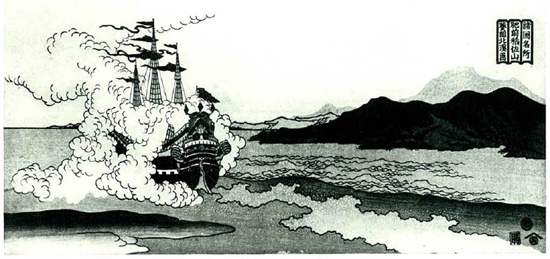

199. HOKKEI: Foreign Warship Saluting. Page 275

200. HOKKEI: Ferryboat in Rain. Page 275

201. HOKKEI: Travelers at Fudo Pass. Page 275

202. HOKKEI: Sumiyoshi Shrine. Page 275

203. HOKKEI: Night Festival at the Seashore. Page 275

204. HOKKEI: Waterfall at Nikka. Page 275

Toyokuni:

THE WAY the seven pages reserved for Toyokuni turned out presents something of a surprise, even to the author. I doubt if any other ukiyo-e artist tried so many distinctive styles as Toyokuni, and this collection is fortunate in having fairly good examples of most of them; so that at one time these seven pages provided a moderately satisfactory cross-section. There were yellow-ground prints copied from Shuncho, big heads done in the style of Sharaku, a beautiful girl that looked as if Utamaro might have done her, some fine hoso-e that looked like Shunsho, and that rhythmic masterpiece, the triptych of princesses tying poems onto the branches of wind-whipped cherry trees, which exists in this collection in excellent condition.

But the more I studied these pages the more convinced I became that the essential Toyokuni resides in his powerful series of single figures standing stark against bare backgrounds, and one by one the other subjects disappeared until at last there stood these seven majestic prints. They represent Toyokuni at his best. Experienced collectors around the world seek these subjects, and they form a fitting capstone to ukiyo-e's honorable tradition of actor prints.

Six of them come from Toyokuni's masterwork, Yakusha butai no sugata-e, "Views of Actors in Role." This series, which has never been catalogued in full, may contain as many as fifty separate subjects, some of which are positively dazzling. The actors are strikingly posed, well drawn, excellently colored, and sometimes graced with mica backgrounds. Each critic has his own preferences as to finest subjects in the series, but Print 209 appears on almost everyone's list. Of his copy, Louis Ledoux wrote: "This print, uniting as it does distinction of composition with fineness of impression and the partly accidental beauty of color and condition brought by time, represents Toyokuni at the highest reach of his achievement in actor prints." By a fortunate accident, Ledoux's copy is now in the Honolulu collection, where it can be compared with the one shown here. At the extreme bottom of the actor's robe, the two prints vary minutely, in that Print 209 has an added ripple, whereas the Ledoux print does not. The series was apparently very popular and probably some of the blocks had to be retouched. The collection also has two fine copies of Print 206, and these show similar minor retouchings of the master block.

Unfortunately, in later years, when the Yakusha butai series became popular with European and American buyers, unscrupulous Japanese dealers bought up as many of Toyokuni's untitled actor prints as possible. It was then a simple matter to carve on a new woodblock the Yakusha butai cartouche and stamp it upon such prints. The collection has a very enticing example of such a forgery. In that respect Print 208 raises special problems, for it is known in another version without the cartouche and with noticeable differences in the background; but it is believed that Toyokuni himself ordered these changes in order to bring a popular single print into a more popular series.

Of Print 211, its former owner J. Hillier, England's leading expert on ukiyo-e, has written that it is "the finest mica-ground Toyokuni in existence," a judgment with which I am not inclined to argue, but some Japanese critics have wondered if the mica dates from Toyokuni's time, a question I am not competent to judge.

Long before I ever thought to own the print which appears opposite in color, I wrote that to me it seemed even better than any of the Yakusha butai series. I still think so.

205. TOYOKUNI: Sawamura Sojuro. Page 276

206. TOYOKUNI: Matsumoto Koshiro. Page 276

207. TOYOKUNI: Ichikawa Komazo. Page 276

208. TOYOKUNI: Nakamura Noshio. Page 276

209. TOYOKUNI: Iwai Hanshiro. Page 276

210. TOYOKUNI: Ichikawa Yaozo. Page 276

211. TOYOKUNI: Onoe Shosuke. Page 276

Minor Masters:

AT THE end of ukiyo-e's vital period, when only the longevity of the last of the great masters, Hokusai and Hiroshige, was delaying the day when the art was to pass into its moribund period, a group of minor artists appeared to produce a handful of prints that were surprisingly good. These men are often ignored both in collections and in literature on ukiyo-e. It would be folly to pretend that they were great artists, for their limitations were so obvious that an assembly of their worst prints-and ninety-five percent of their output falls into that classification-could be used as an example of why ukiyo-e died. But interspersed with their horrors-poorly designed, poorly drawn, and wretchedly colored-one comes upon occasional prints that are exciting, seven of which are here presented.

Kunimasa was born a little early to qualify as a typical member of this group, and the general quality of his output was higher than that of the others here mentioned, but he was such a minor artist that he fits in here. One does not expect him to do fine prints, yet the three portraits shown here have always commanded attention, while the one reproduced in color has become almost the symbol of the prints of this period. It has been widely reproduced in Japan, is the subject of numerous copies, and has recently been transformed, by a series of nine large ceramic tiles, into a huge and striking wall decoration. It is a most appealing print and if it were not known to be by Kunimasa, I would judge it to be one of the better Shun'eis. Print 214 has also enjoyed a favorable reputation in Japan and is a fitting subject with which to end our series of big heads: the hero tugs at the ends of his towel lest, as I have been told, he fall backward in disgrace after having had the courage to disembowel himself.

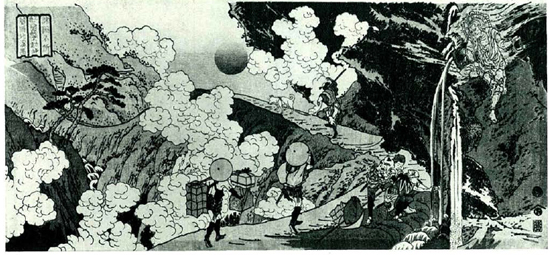

Kuniyoshi has always been a minor favorite of mine, for working alone he discovered many of the principles of contemporary art and applied them to a marvelous series of prints, not well received at the time of issue but later recognized for the pioneering work they were. Print 216 is a good example of this style, for here in some strange way Kuniyoshi anticipates many of the devices that were to come later in Europe. Only the fact that I have reproduced elsewhere his masterpiece in this form, the night raid of the ronin, prevents me from using it here, for it is an excellent print and a landmark in Japanese art history. Print 215 shows another unexpected aspect of Kuniyoshi's work, his experiments in European-style draftsmanship; the woman to the left is almost the same as that drawn repeatedly by the minor Italian master Beccafumi.

Print 217 is a unique gem, Kunisada's futuristic study of the planes created in nature by a heavy mist falling capriciously across a ravine. It is an extraordinary print, difficult to reproduce but startling in effect. Like earlier critics, I find it difficult to believe that Kunisada was capable of such work, but he signed it.

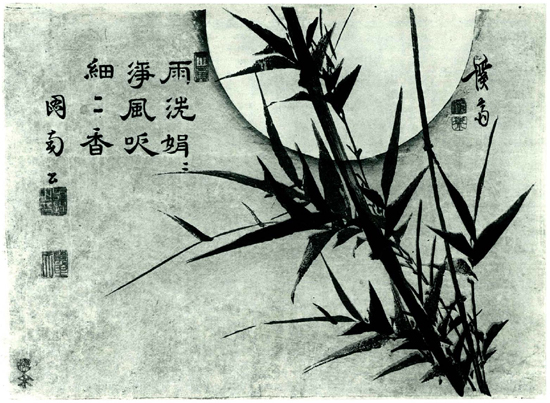

I found Print 218 at the bottom of a pile. I know nothing about it, except that Eisen, a man of little taste, designed it, and I have never seen it reproduced or discussed, but all who see it agree that the mottled background, the perfect placement of the bamboo, and the severe Chinese lettering combine to make a haunting work. Anyone who looks constantly among the odds and ends of ukiyo-e usually comes up with some unexpected pleasure, like the seven prints shown in this group, and this is one of the rewards of Japanese prints: the field is far from exhausted. In Paris, in London, or in San Francisco tomorrow, one may come upon some unheralded print which he will always regard as highly as I regard this superb Eisen. And the joy of such discovery is that no critic has ever said that the print is meritorious. This is a decision that each discoverer must make for himself, and in the major historical fields of art only in ukiyo-e is this intellectual adventure available almost daily.

212. KUNIMASA: Ichikawa Ebizo. Page 276

213. KUNIMASA: Nakamura Noshio. Page 276

214. KUNIMASA: Ichikawa Danjuro. Page 276

215. KUNIYOSHI: Kuo CM Finds the Pot of Gold. Page 276

216. KUNIYOSHI: Tile-kilns at Imado. Page 276

217. KUNISADA: Landscape in Mist. Page 277

218. EISEN: Bamboos and Moon. Page 277

Hiroshige:

IT IS IRONIC that a man who once wrote, "Hiroshige's work has never charmed me as it does most collectors," should wind up, as I have done, the chance custodian of what Judson Metzgar called: "America's finest private collection of Hiroshige. Schraubstadter's was larger but lacking in the wonderful quality that marks these Chandler prints." From this wealth it has not been easy to select a mere eleven that will do justice to the man.

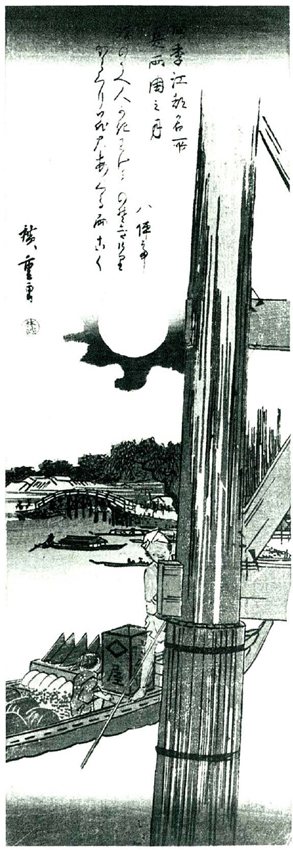

Others think more highly of the long letter-sheets than I, but I do recognize them as free, flowing statements of nature, more poetic in concept than some of his other work, and it has here been possible to give them the full sweep they deserve. "Sudden Rain at Ohashi" well exemplifies Hiroshige's famous rain and is the print that moved Van Gogh to paint his own glowing copy of it. The snow scene from Wakan roei shu is the masterpiece from one of Hiroshige's finest series, while the two panels facing it are choice items from his narrow views of Edo. Print 224 has always been avidly sought by collectors, and with reason, for it is a happy composition in fine color and marked with Hiroshige's best style. Print 228 has been termed ukiyo-e's greatest nature print, a judgment I find no difficulty in accepting; note how extraordinarily Japanese it is, how exactly right the three elements of nature-bird, rain and tree-are handled, how flawless the design and coloring.

But so far as this collector is concerned, the most important print in the book is 229, not because it is undoubtedly one of the sublest works ever produced in print form, and not because it was chosen by Robert Treat Paine, Jr., to illustrate his essay on ukiyo-e, but because it was the first Japanese print I ever saw. It was shown to me many years ago by a tenderhearted woman in Buffalo, Mrs. Georgia Forman, and I believe I sensed then all I was one day to discover in ukiyo-e. Years later, in Afghanistan, I received a most improbable letter from Mrs. Forman's son. He said that on the morning of his mother's death she had unexpectedly thought of the afternoon she had shown mc her best Hiroshige: "And she said, 'Why should I leave my prints to a museum that may appreciate them... or may not? Wh y not leave them to Michener?'" She had neither seen me nor written to me for twenty-five years, and yet she remembered that I had shared her enthusiasm for this Hiroshige; upon her gift of prints my collection has been built.

In 1896, Ernest Fenollosa concluded die first important American essay on ukiyo-e with an obiter dictum that was to become famous: a list of the more important artists classified into three groups of descending excellence. In 1915 Arthur Davison Ficke updated the list. Today I would classify the major artists roughly as follows. In each group the artists appear in the same order as in this book. The first number shows Fenollosa's judgment in 1896; the second, Ficke's in 1915; an asterisk means that the artist in question did not appear on that list. Observe that neither critic had yet heard of Sugimura Jihei and that neither thought much of Kuniyoshi, whose work I heartily admire.

| First Group | ||

| Moronobu | 2 | 1 |

| Kiyonobu | 2 | 2 |

| Masanobu | 1 | 1 |

| Harunobu | 1 | 1 |

| Kiyonaga | 1 | 1 |

| Utamaro | 2 | 1 |

| Sharaku | * | 1 |

| Hokusai | 1 | 1 |

| Second Group | ||

| Sugimura | * | * |

| Kaigetsudo | 2 | 2 |

| Kiyomasu | 2 | 2 |

| Toyonobu | 3 | 2 |

| Koryusai | 2 | 1 |

| Buncho | 3 | 2 |

| Shunsho | 3 | 1 |

| Choki | * | 2 |

| Toyokuni | 3 | 2 |

| Hiroshige | 3 | 1 |

| Third Group | ||

| Shigenaga | 3 | 2 |

| Kiyohiro | 3 | * |

| Kiyomitsu | 3 | 2 |

| Shunko | * | 3 |

| Shun'ei | * | 3 |

| Shigemasa | 2 | 2 |

| Shuncho | 2 | 2 |

| Eishi | 3 | 2 |

| Kuniyoshi | * | * |

219. HIROSHIGE: The Salt-beach at Gyotoku. Page 277

220. HIROSHIGE: Sudden Shower at Ohashi. Page 277

221. HIROSHIGE: Cherry Blossoms at Koganei. Page 277

222. HIROSHIGE: Mountain Village. Page 277

223. HIROSHIGE: By Ryogoku Bridge. Page 277

224. HIROSHIGE: Autumn Moon over the Yoshiwara. Page 277

225. HIROSHIGE: Moon through Leaves. Page 278

226. HIROSHIGE: Plovers in Flight. Page 278

227. HIROSHIGE: Wild Geese in Flight Page 278

228. HIROSHIGE: Cuckoo in Flight. Page 278

229. HIROSHIGE: Evening Bell at Mii Temple. Page 278