Section

4:

THE MODERNS

MOST COLLECTIONS of Japanese prints and most works dealing with them end with Hiroshige; and this is not illogical, for following the death of that great master in 1858 there can be no question but that the art of traditional ukiyo-e declined sharply. A dreary sequence of hacks, known as the Kunfs and the Yoshi's-a recent work lists eighty undistinguished artists whose names begin with the former character and fifty-seven beginning with the latter-poured forth an endless series of prints marked by cluttered design, boring historical content, and some of the most garish coloring ever seen in serious art. Because most of those later prints were abominable, it became fashionable for critics to ridicule all work done after 1858, and some extremely sweeping condemnations have been made by otherwise perceptive critics. I prefer not to embarrass anyone by digging up a series of such judgments; but I must point out that if one were to accept such criticism blindly, no print that appears in this last section would be worth collecting. My contention is otherwise: after the dreadful flood of garish color prints, a good many artists went seriously to work to see what could be done to rescue the art from extinction, and the first five prints offered here show what was accomplished.

The five have these attributes in common: They appeared after the high tide of ukiyo-e. They were definite attempts to revive a dying art. Each was produced in the old way; that is, the artist drew his sketch, the woodcarver carved it on a block of cherry wood, the printer applied the colors to the finished block and struck off the copies. And except in the case of Print 233, the finished copies were peddled to the public by a professional publisher. In other words, Print 234, which so far as I am concerned is the last great print produced in the classic tradition, is technically not a bit different from Print 1, which appeared about 156 years earlier.

I am very fond of these five prints and consider them markedly underpriced in present markets, for they are of fine quality, have a content which appeals to me, and are worthy echoes of a great past. I cannot understand any theory of art which would condemn them to oblivion; for if one is eager to be in at the birth of an art, and if he wants to own an album sheet so that he can remember what happened in those far-off days, he ought also to be interested in the decline; and it is with Kiyochika, Goyo, and Shinsui that we witness the actual end of ukiyo-e.

Why were these five prints, excellent as they are, not sufficiently strong to keep the traditional print-making process alive? Four explanations come to mind: the subject matter was circumscribed and old-fashioned, so that modern taste could not take it seriously; the color harmonies were muted at a time when color in Western art was becoming increasingly bold; the precise and refined techniques of carving and printing were more appropriate to the age of Harunobu than to the age of Picasso; and there was nothing in the art that allied it with the great movements that were sweeping the rest of the world, where techniques were rough, colors vibrant, and content psychological. Traditional print-making, even in these marvelous final examples, had lost itself in a culde-sac, and it is with a feeling of mournful affection, rather than of vital participation, that I revere these last prints.

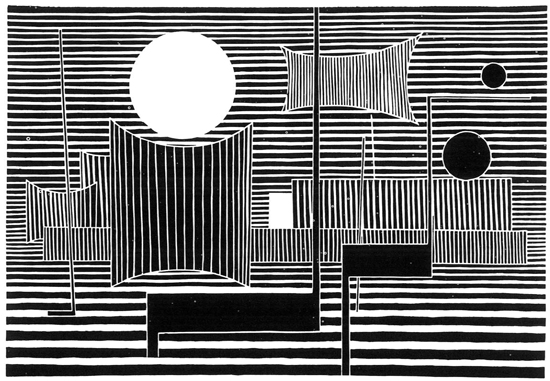

But with Print 235 I enter a joyous new world, and one in which I feel at home. Take a moment to leaf through the twenty-two prints shown in these last pages. Try to determine which betray the fact that they were done by Japanese artists. I find thirteen that give no evidence at all that they were of Oriental derivation. They stand forth as competent examples of the best in international art. The men who did them have obviously shaken themselves free of antique preconceptions and exist as blood-brothers to Picasso, Mondrian, Marin, and Gauguin. This is the great accomplishment of the modern Japanese print: it has set free both the artist and his technique.

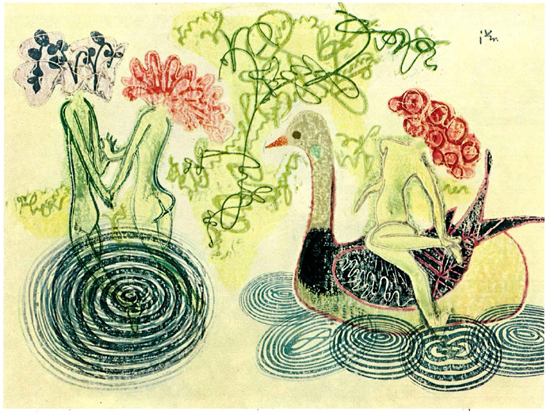

At the same time, look at Prints 237 and 254. These are as Japanese as a Harunobu or an Utamaro. They revive the loveliest traditions of an ancient subject matter, and reveal that some of the most eloquent Japanese content in the history of print-making is being utilized today. This is the second outstanding accomplishment of the modern print: it has provided the artist with techniques for preserving what is essentially Japanese in his tradition. Thus the modern artist can utilize subject matter that is either international or intensely national, and he can accomplish fine work with either. This is one of the earmarks of a mature art.

The technical development which differentiates these later prints from all that precede is the fact that each has been drawn, carved, printed and published by the artist himself, a difference the artists have emphasized by calling their works sosaku hanga, "creative prints," not ukiyo-e. Thus, when you look at the glowing Onchi 242, you are seeing only his handiwork. Where possible, he even ground his own colors, and if he had been able to lay the paper himself, he would have done that too. Because the formal techniques used in the classic period of print-making had led to formalized art, the modern artists felt obligated to perform all functions themselves. Thus, when Yamamoto, the artist responsible for Print 235, saw what vigorous work European artists were accomplishing by cutting their own blocks, he established the principle that Japanese must do the same; and much of the wild power of the modern Japanese print stems from this precept of Yamamoto's. For example, Print 243 shows an insolent disregard for precise cutting, perfect registry, and exact handling of color. In seeking new freedoms the artists who made these prints were taking a step essential to the revitalization of Japanese print-making.

From what I said in the Introduction, it is obvious that I do not place much emphasis on the specific technique whereby a work of art is created. I feel reasonably sure that Yamamoto and his followers could have achieved with old-style block-cutters and old-style printers the fine work they ultimately accomplished, and I give none of the credit whatever to the fact that they elected to carve their own blocks; but the significant factor is that they thought they had to do so, and anything that will help the individual artist attain the freedom to do singing, soaring work is to be treasured. If these men thought they had to cast aside the old carvers and printers, then they were entitled to do so, even if in reality the step was not so essential as they thought. With that qualification, this is the third significant accomplishment of the modern print: it allows die artist himself to control each step of its creation.

Other characteristics are self-evident. The prints are much bigger than before; previously their size was determined by the size of board that could be cut from a cherry tree, but modern artists often forswear solid cherry in favor of plywood. Colors are much bolder; the muted harmonies so loved by Harunobu and Kiyonaga are not often seen, for the bright international palette has triumphed. Abstract designs are becoming common; and contrary to sentimental taste which would require the Japanese artist to restrict himself to antique themes, this is an appropriate development, for the Japanese have always been strongly inclined toward abstraction, as indicated in their ceramic and kimono patterns. Finally, the modern print is apt to have a profounder psychological content than those of the classical period; it is true that Sekino's fine study of Lafcadio Hearn, Print 236, stems directly from Sharaku, but Onchi's vision, Print 243, and Hatsuyama's, Print 253, derive from no Japanese antecedents; they are new and part of the total international art movement.

There is one point about these modern prints that rises frequently to plague me. Well-intentioned people, looking at them, often exclaim: "Isn't it a pity that the artists no longer do Japanese scenes like Hokusai and Hiroshige." I am afraid this is what must be termed "the tourist approach to art criticism." One wants a Dutchman to paint windmills and wooden shoes, an Italian to do madonnas in red shawls, and a Mexican to create sleeping Indians in big hats. This type of criticism demands that if an artist is Japanese he is obligated to paint geisha girls, cherry blossoms, and Mount Fuji. Carried to logical absurdity, what such critics contend is that it is all right for a Spaniard like Picasso or an American like Pollock or a Russian like Chagall to paint in an international style, but it is forbidden for a Japanese to do so. I find no logic in this whatever. There surely can be no categorical imperative for unborn generations of artists to keep on turning out pale copies of Hokusai and Hiroshige, just to titillate tourist appetites. Let the modern artist work as his will dictates, and the tourists of a later age will mysterious y grow to recognize his work as the essence of things Japanese. It is unthinkable that an artist should be arbitrarily confined to any one subject matter, or denied full membership in the international society of creative minds. In Japan, the modern print artist has labored diligently to prove this point.

But perhaps I am not an unprejudiced critic, for I confess a special affection for these modern prints. I have known most of the artists represented here and for some years have followed their work. By a fortunate accident I helped bring Onchi and Hiratsuka to the attention of an international audience; and before most of these men were as well known as they now are, I experienced the joy of discovering for myself what I thought of their work. It is their prints that I keep on my walls at home. It is their work that speaks to me in contemporary accents. For each classical print that I study, I find myself reviewing two or three of these strong, vibrant moderns. I am excited by them, and I love them. I am convinced that in years to come the artists shown here will be increasingly recognized as worthy revivers of an art form that in its classical manifestation had died; and to revitalize an art, even if one has to modify the techniques that helped make it strong originally, is no mean accomplishment.

My respect for these men transcends their artistic successes, for I well know with what dedication they have labored through lean years. Men like Onchi, Hiratsuka, and Yamaguchi are more courageous men than I, and now that one international jury after another is awarding them first prizes for the best print work being done in the world today, I am most happy. If a collection of art must inescapably be a portrait of the man who assembled it, I would be content to be represented by Prints 244 and 245. They are of my spirit.

The book closes with two panels, Prints 255-56, from one of the most profound works of art produced in Japan in this century, and certainly one which has received more international acclaim than most. In 1939, Munakata Shiko, one of Japan's most distinguished print artists and a man of abounding vitality, issued a series of towering sumizuri-e titled The Ten Great Disciples of Buddha, including the ten disciples and two bodhisattvas. These twelve dynamic prints have won numerous awards in exhibitions throughout the world. They form a fitting conclusion to a vivid journey.

OF ALL the prints represented in this book, those in this next group have been most ignored by scholars, if not by the general public, for in spite of the fact that they have been widely bought, so that in many parts of the world there are numerous respectable collections covering this period, there is no satisfactory treatise dealing with these artists and no critical account of their work. This is a regrettable omission, and one that should be corrected, for it was by means of these ingratiating, if not great, works that hundreds of collectors came to know Japanese prints-, and a careful review of what these men accomplished will go far toward correcting the easy assumption that after Hiroshige the Japanese print was completely dead. It was moribund, and the fire infused into it by men like Sharaku and Hokusai was no more, but it continued underground, as it were, as a respectable minor art, and when this period has been summarized by some careful scholar with a critical eye and a discerning appreciation, we will close a painful gap in our knowledge.

The five artists whom I have chosen as typical of this attractive, quiescent period are varied. No pages in this book give me more personal pleasure than the next three. From the first day I planned this work I intended using these three prints, exactly as they appear here, but I was six years in finding them, for they turned out to be extremely rare. The Kiyochika reminds me of Ryder and shows what Japanese artists, working alone, were accomplishing. It is a moody, evocative masterpiece. The Ryuson stands apart in my affections, for it seems to me to summarize the end of an epoch. The moon is rising on this night over a Tokyo that will soon be no more; as ukiyo-e dies, so dies the ancient life. There are many Japanese who feel the same way about this print, which is why I feared I would never find a copy. Then on the last day in winch I was to be in Japan, Adachi Toyohisa, the famous publisher of ukiyo-e reproductions, came with the news that he had found a copy of this night scene and that a friend had uncovered the Kiyochika "Hiki-fune." They were the last prints I acquired in Japan and among the most meaningful.

I left resigned to the fact that I would have to publish without the Yasuji, for copies were simply not available; but a year later and only days before the plate-maker reached tins section of the book, Shobisha, the Tokyo dealer, sent word that a copy had been found. If the Ryuson signalizes the end of one age, this famous, impressionistic Yasuji heralds the beginning of another: Western-style canned goods and gas lights have arrived on the Ginza!

I especially commend these two pages, Prints 231 and 232, for they summarize the meaning of this book: the old passes in a moment of positively haunting beauty, the garish new is inevitable and it is the artist's job to hammer it into some semblance of beauty. These are prints at their best: reportorial, widely disseminated, artistic, compelling to the eye. I truly love these two pages.

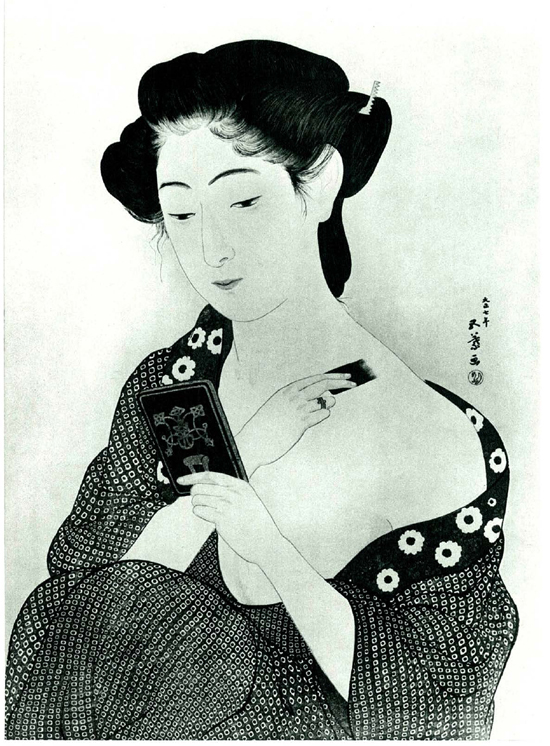

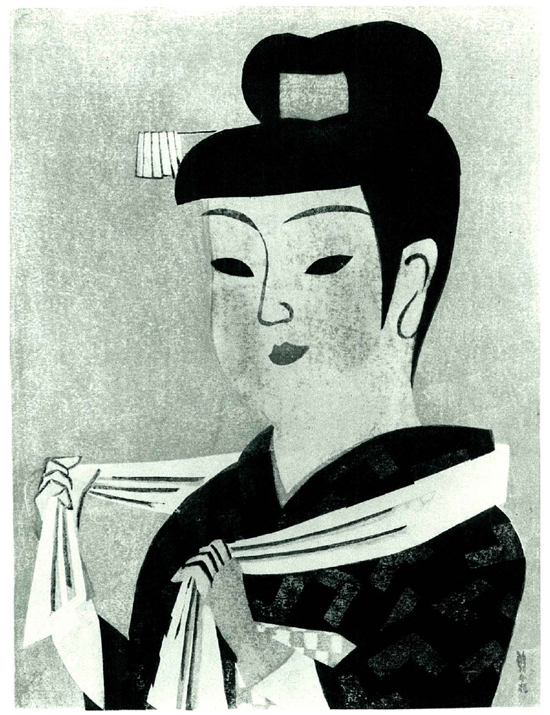

Goyo's delicate portraits of women are justly famous, their reputation being somewhat tarnished by the fact that most examples available today are post-humous copies issued by men who got hold of the original blocks. And the Shinsui serenader is a flawless print made by a painter still living in Tokyo. It is not inappropriate to place it at the very end of a great tradition.

If more pages had been available for these dying days of ukiyo-e, I would have included representative prints by these artists Kyosai, who did inky-black crows, and Zeshin, whose studies of mice are delectable; Yoshida Hiroshi, who almost alone kept the antique art alive with a prodigious output; Yamamura Koka, whose modern portraits of actors are held by Japanese to rival Sharaku's; and Hasui, the best known of the group. But it was a period with which I myself am not particularly attuned, and I must leave its description to others.

230. KIYOCHIKA: Pulling the Canal-boat. Page 278

231. RYUSON: Moonlight at Yushima. Page 278

232. YASUJI: Shop on the Ginza. Page 278

233. GOYO: Woman at Toilette. Page 279

234. SHINSUI: Samisen Minstrel at Ikenohata. Page 279

First Group:

NO PRINT in this book is more important than the one which appears opposite this page. Its effect upon Japanese print-making was cyclonic, and much of today's accomplishment stems from this print, and from others which Yamamoto sent back to Japan from his artistic explorations in Paris in the years 1912-14. It is the first print in this book which in no way betrays its Japanese ancestry. It was conceived, drawn, carved, colored, and printed in European style, but of course the superb paper had to be Japanese; no other would do.

It is a revolutionary print and almost by itself thrust the entire world of Japanese print-makers into the orbit of men like Van Gogh, Kandinsky, Munch, and Kokoshcka. From this time on the precise, meticulously carved blocks of ukiyo-e are gone. The new artists will carve with bold strokes, and they will use the wood as a major component of their designs. Areas will be modeled, shadows used, and forms carefully built up. Bright new color combinations will become popular and a bold impressionism featuring European characteristics will predominate. That is why Yamamoto Kanae's portrait of the Breton girl is one of the most revolutionary prints ever issued. After it flashed through Tokyo, no serious artist could go back to the classical style.

Yamamoto's greatest prints are those showing European subjects, especially his Russian landscapes. This collection is fortunate in owning eight fine examples, but the one shown here most strikingly illustrates Yamamoto's effect upon his contemporaries: it is so modern, so un-Japanese, so much within the sophisticated international tradition that it merits our special attention. That it reached me from the hands of Oliver Statler, a young American from Chicago who worked in Tokyo with the Army of Occupation and who in his book Modern Japanese Prints launched the serious study of Yamamoto and contemporary prints, adds to its attractiveness for me.

The Sekino, Print 236, is especially noteworthy in that it represents the American who did the most to explain Japan to the West, Lafcadio Hearn. His portrait well illustrates the way in which Yamamoto's successors adapted his lessons, but for me the print has an unusual personal importance. A few days before his death, Judson Metzgar, last of the original group of American ukiyo-e connoisseurs, entertained me in his Los Angeles home, and when we had finished studying his collection of classical ukiyo-e, he showed me a print which he had come especially to love, and it was this modern Sekino. It thus became the last print that the great classicist Metzgar sold and testifies that even he was converted to modern work.

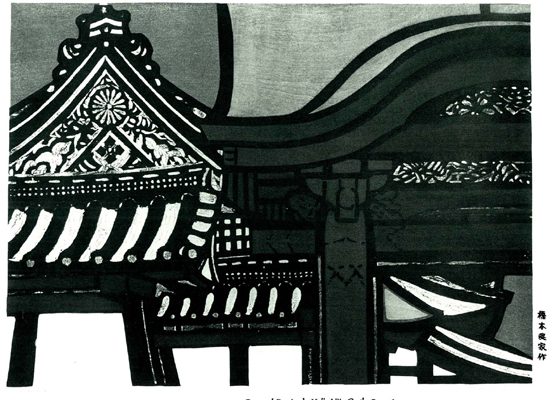

The output of Saito Kiyoshi, represented here by Print 238, which I especially treasure because it came to me from William Hartnett, another American who served with the Occupation and who first drew the world's attention to what was happening in Japanese print circles, is widely known in America. Saito is amazingly skilled as a craftsman, a fine designer, and a man imbued with a sense of things Japanese.

The Hashimoto, Print 241, is of value to students in that the copy shown here is accompanied, at Honolulu, by ten preliminary pencil sketches, five trial paintings in rough oil, two proof sheets of the key block, and a complete set of the six printing stages required to produce the finished print. With such a wealth of material, it thus becomes an encyclopedia of modern print-making.

235. YAMAMOTO KANAE: Woman of Brittany. Page 279

236. SEKINO JUN'ICHIRO: Lafcadio Hearn in Japanese Costume. Page 279

237. MAEKAWA SEMPAN: Akita Dancer. Page 279

238. SATTO KIYOSHI: Winter in Aizu. Page 279

239. KAWANO KAORU: Girl in Shell. Page 280

240. MABUCHI THORU: Afternoon Sun. Page 280

241. HASHIMOTO OKIEB: Gate and Retainer's Hall, Nijo Castle. Page 280

Onchi:

THE COLLECTION represented in this book will never be remembered for its 45 Masanobus, because any attentive collector ought to be able to acquire equivalent prints over the next ten years; surely they will come on the market. Nor will it be remembered for its 108 rather handsome Harunobus, for these prints appear regularly in major sales and in much less than a decade a collector could well surpass what this collection has to show. In the past the collection has been favorably known for its wealth of Hiroshige prints, but with a little care any collector could duplicate these, for Hiroshiges are quite easy to acquire.

But I believe that the 44 Onchis in this collection will be long remembered, for I am convinced that this powerful, gifted man will ultimately be recognized as the genius of this period of print-making. His prints were few in number, with rarely more than half a dozen to an edition. But they were highly prized both by his contemporary artists and by a discerning group of collectors. Few are now coming on the market, and it was only because others associated with the production of this book counseled restraint that I forswore presenting here eight or ten of his finest works. Certainly, my taste inclined me toward doing so.

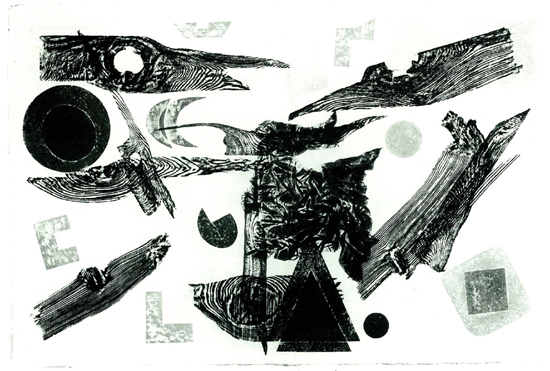

Onchi Koshiro died in 1955, a tall, gray-haired, lively poet with a fine acid sense of humor. He was a wonderful man to know, for he laughed most of the time and his ready wit played upon many subjects. He was a brave man and during World War II had the fortitude to combat the military nonsense then rife in Japan. Above all, he was an international spirit, roaming the entire world. He felt himself a brother to Munch of Norway and Kandinsky of Russia. He signed his name in European characters and used French and German titles for his work. Above all, he was a magnetic, vital human being, absorbed in aviation, in the study of nature, and like so many Japanese intellectuals, in the symphonic music of Beethoven, Brahms, and Bruckner. As a man he was an adornment to his society.

As a print artist his ultimate effect was even greater than that of Yamamoto Kanae, for he produced more work, at a time when numbers of young men could come into contact with him. Also, since he came from samurai stock, he had entree to circles denied most of his fellow artists. He was therefore a towering influence, and his cavalier attitude toward materials, using anything so long as it helped him create a vibrant, poetic print, was instrumental in setting his contemporaries free from their servitude to wood, its professional carvers, and its professional printers. With splash and abandon, Onchi used

. glass, waxed paper, string, glued leaves, and charcoal. His printing was apt to be impressionistic rather than meticulous, and his results were scintillating rather than controlled.

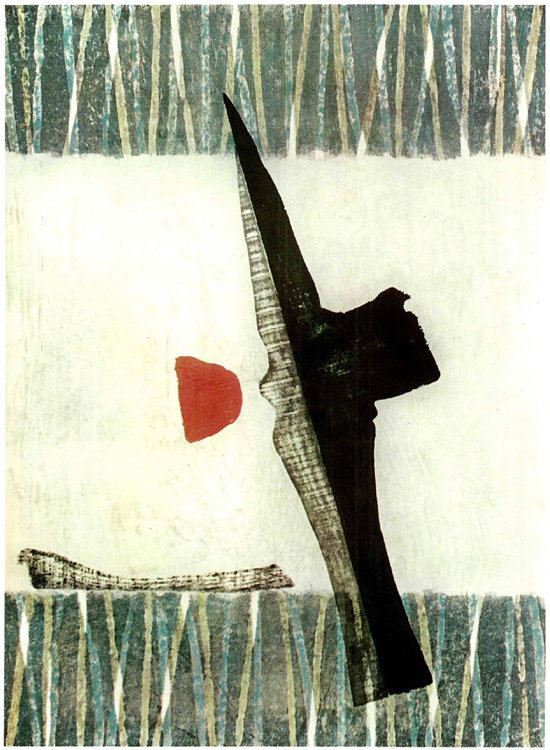

It has been especially difficult for me to select the three best Onchis, for I ruled out his superlative portrait of the poet Hagiwara, which I have published elsewhere, and one of my prime favorites, "Object Number 2," which is handsomely reproduced in color by Statler, who also uses up two other choice subjects, "Poem Number 8" and "Poem Number 22." Thinking it important that we see as much as possible of Onchi's work, I have avoided the foregoing. By far the best Onchi I know is Print 244, but I have been advised that it might not reproduce well in color, since it stresses muted blues. The principal omission both in this book and in Statler's is that series of great final prints where Onchi, who knew death was near, utilized phallic symbols with astonishing power. It was appropriate that this wild, free spirit should end with such thoughts.

242. ONCHI KOSHIRO: Loneliness. Page 280

243. ONCHI KOSHIRO: Caricature No. 8. Page 280

244. ONCHI KOSHIRO: Poem Number Nineteen: The Sea. Page 280

Second Group:

WHEN YAMAGUCHI GEN was in the midst of making the print which appears opposite, he wrote me a letter that summarizes the problems which have always beset Japanese print artists: "For many years I have been working at my art and at times I have not had the courage to go ahead. I have had to watch the work done by men like me ignored, abused, and left unsold. Some critics avoid us because we do not work in the old style, and others say harsh things because we do not copy old Japanese themes. It has been a very hard life indeed to bear such indifference and recently I have often thought about stopping. But the great interest you and Mr. Statler have shown in my work makes me believe that I am doing right. So I keep working."

As anyone can see, the print that came out of the spirit of that letter, which reached me almost a year late while I was working in northern Burma, is a marvelous, poetic thing, and I would be gratified beyond expression if I thought that anything I had said had encouraged a man to stay at such work. But Yamaguchi is a tough-minded man, and the next print after this one went to the international exhibition in Lucerne, where it won the world's number one award. It was very good to be with Yamaguchi when he got word and to see him win belatedly the accolades he had so long deserved.

Almost every print in this section reminds me of the circumstances under which I got it from its creator. For example, I did not want to publish this book without at least one example from the remarkable Yoshida family, worthy successors of Yoshida Hiroshi, yet out of all their work I could not find a print that fitted my page requirements, until late one wintry afternoon I was looking through a stack with Yoshida Hodaka and came upon Print 249. How striking its Mexican motifs seemed then, and now!

It is a special pleasure to be able to reproduce one of Uchima Ansei's prints, 251, for he is a young American-born Japanese who was trapped in Japan during the war and who applied his time to the study of painting. In 1955 Uchima turned to print-making with striking success. And Shinagawa Takumi's abstraction, Print 252, is a joy, with its emphasis on textures and vivid color; the day I got it, Shinagawa said: "I'm so glad you are willing to buy an abstraction. For weeks everyone has been taking only formal prints."

The Hatsuyama Shigeru, Print 253, has a story of its own. This fine artist, who illustrates children's books with wildly imaginative charm, is so popular as a print-maker that the few he produces are instantly sold. I therefore had little chance of acquiring any good copies, but when I visited him on the edge of Tokyo he said: "I work in books and you work in books. I will not sell you any prints, but I will give you all you want, and when you return to America, you will send me a crate of children's books, because I want to see how your illustrations compare with mine." For that reason, this collection has about two dozen of the choicest Hatsuyamas, of which the one shown here is a fine example.

I have written elsewhere of my dear friend Hiratsuka Un'ichi. I see him now in his cluttered study, wearing a Russian-type smock close-buttoned at the neck, a little wisp of a man, with a goatee and the kind of childish wonder in all things that anyone who works with words wishes he could preserve in his own life. That Hiratsuka also did the print which appears on the back jacket-flap of this book is a particular satisfaction.

And if the reader can visualize a wall bearing a frieze of tall, black figures like Prints 255-56, he will understand why the work of Munakatahas been so highly praised and why today, as at the beginnings of ukiyo-e, the sumizuri-e technique still produces the most powerful prints.

245. YAMAGUCHI GEN: Deep Attachment. Page 280

246. NAKAO YOSHITAKA: Figure. Page 280

247. AZECHI UMETARO: Bird in Safe Hands. Page 280

248. KINOSHITA TOMIO: Masks: Design 4. Page 280

249. YOSHIDA HODAKA: Ancient People. Page 281

250. YOSHIDA MASAJI: Fountain of Earth No. 1. Page 281

251. UCHIMA ANSEI: Song ofthe Seashore. Page 281

252. SHINAGAWA TAKUMI: Here Everything Was Alive. Page 281

253. HATSUYAMA SHiGERU: Flowers, Birds. Page 281

254. HIRATSUKA UN'ICHI: Horyu-ji in Early Autumn. Page 281

255. MUNAKATA SHIKO: Ubori Page 281

256. MUNAKATA SHIKO: Kasen'en. Page 282

257. MORONOBU: Stroll by the Bay (detail) Page 254