AEH, aged seventy-seven and getting no older, wearing a buttoned-up dark suit and neat black boots, stands on the bank of the Styx watching the approach of the ferryman, Charon.

AEH I’m dead, then. Good. And this is the Stygian gloom one has heard so much about.

Charon Belay the painter there, sir!

AEH ‘Belay the painter!’ The tongues of men and of angels!

Charon See the cleat. I trust you had grieving friends and family, sir, to give you a decent burial.

AEH Cremation, but very decent I believe: a service at Trinity College and the ashes laid to rest – for fathomable reasons – in Shropshire, a county where I never lived and seldom set foot.

Charon So long as the wolves and bears don’t dig you up.

AEH No fear of that. The jackals are another matter. One used to say, ‘After I’m dead’. The consolation is not as complete as one had supposed. There – the painter is belayed. I heard Ruskin lecture in my first term at Oxford. Painters belayed on every side. He died mad. As you may have noticed. Are we waiting for someone?

Charon He’s late. I hope nothing’s happened to him. What do they call you, sir?

AEH Alfred Housman is my name. My friends call me Housman. My enemies call me Professor Housman. Now you’re going to ask me for a coin, and, regrettably, the custom of putting a coin in the mouth of the deceased is foreign to the Evelyn Nursing Home and probably against the rules. (looking out) Doubly late. Are you sure?

Charon A poet and a scholar is what I was told.

AEH I think that must be me.

Charon Both of them?

AEH I’m afraid so.

Charon It sounded like two different people.

AEH I know.

Charon Give him a minute.

AEH To collect myself. Ah, look, I’ve found a sixpence. Mint. 1936 Anno Domini.

Charon You know Latin.

AEH I should say I do. I am – I was, for twenty-five years, Benjamin Hall Kennedy Professor of Latin at Cambridge. Is Kennedy here? I should like to meet him.

Charon Everyone is here, and those that aren’t will be. Sit in the middle.

AEH Of course. Well, I don’t suppose I’ll have time to meet everybody.

Charon Yes, you will, but Benjamin Hall Kennedy isn’t usually first choice.

AEH I didn’t mean to suggest that he is mine. He imputed to the practice of translation into Greek and Latin verse a value which it does not really possess, at least not as an insight into the principles of ancient metre. It stands to reason that you are not likely to discover the laws of metre by composing verses in which you occasionally break those laws because you have not yet discovered them. But Kennedy was a schoolmaster, a schoolmaster of genius but a schoolmaster. It was only in an outbreak of sentimentality that Cambridge named a chair after him. I would have countenanced a small inkpot. Even so, let it be said, it is to Kennedy, or more directly to his Sabrinae Corolla, the third edition, which I received as a school prize when I was seventeen, that I owe my love of Latin and Greek. In Greek I am, as it were, an amateur, and know hardly more than the professors: well, a great deal more than Pearson, who knew more than Jowett and Jebb (knew) combined. As Regius Professor of Greek when I was at Oxford, Jowett was contaminated by a misplaced enthusiasm for classical education, which to him meant supplying the governing classes with Balliol men who had read some Plato, or with Oxford men who had read some Plato when Balliol men who had read some Plato were not available. In my first week, which was in October 1877, I heard Jowett pronounce ‘akribos’ with the accent on the first syllable, and I thought, ‘Well! So much for Jowett!’ With Jebb it was Sophocles. There are places in Jebb’s Sophocles where the responsibility for reading the metre seems to have been handed over to the Gas, Light and Coke Company.

Charon Could you keep quiet for a bit?

AEH Yes, I expect so. My life was marked by long silences.

Charon unties the painter and starts to pole.

Who is usually first choice?

Charon Helen of Troy. You’ll see a three-headed dog when we’ve crossed over. If you don’t take any notice of him he won’t take any notice of you.

Voices off-stage – yapping dog, splashing oars.

Housman … yea, we have been forsaken in the wilderness to gather grapes of thorns and figs of thistles!

Pollard Pull on your right, Jackson.

Jackson Do you want to take the oars?

Pollard No, you’re doing splendidly.

Three men in a boat row into view, small dog yapping. Housman in the bow (holding the dog), Jackson rowing, Pollard in the stern. The dog is played realistically by a toy (stuffed) dog.

Jackson Hous hasn’t done any work since Iffley.

AEH Mo!

Housman The nerve of it – who brought you up from Hades? – to say nothing of the dog.

Pollard The dog says nothing of you. The dog loves Jackson.

Housman Jackson loves the dog.

Pollard The uninflected dog the uninflected Jackson loves, that’s the beauty of it. Good dog.

Housman The uninflected dog can’t be good, dogs have no soul.

Jackson What did he say?

Pollard He said your dog has no soul.

Jackson What a cheek!

Pollard It just goes to show you don’t know much about dogs, and nothing at all about Jackson’s dog whose soul is already bespoke for the Elysian Fields, where it is eagerly awaited by many of his friends who are not gone but only sleeping.

AEH Not dead, only dreaming!

The three men row out of view, arguing ‘Pull on your right!’ … ‘Is anybody hungry?’

Charon Well, I never! Brought their own boat, whatever next?

AEH I had only to stretch out my hand! – ripae ulterioris amore! (cries out) Oh, Mo! Mo! I would have died for you but I never had the luck!

Charon The dog?

AEH My greatest friend and comrade Moses Jackson. ‘Nec Lethaea valet Theseus abrumpere caro vincula Pirithoo.’

Charon That’s right, I remember him – Theseus – trying to break the chains that held fast his friend, to take him back with him from the Underworld. But it can’t be done, sir. It can’t be done.

Charon poles the ferry into the mist.

Light on Vice-Chancellor in robes of office. His voice is echoing. Alternatively, he is heard only.

Vice-Chancellor Alfredus Edvardus Housman.

Housman, aged eighteen, comes forward and receives a ‘book’ from him.

Alfredus Guilielmus Pollard … Moses Johannus Jackson …

Light on Pollard, eighteen, and Jackson, nineteen, with their statute books.

Pollard A hoop, in the accusative.

Jackson ‘Neque volvere …’

Pollard Yes, we are forbidden by the statutes to trundle a hoop. I’m Pollard. I believe we have the two open scholarships this year. May I offer my congratulations.

Jackson How do you do? Well, congratulations to you, too.

Pollard Where were you at school?

Jackson The Vale Academy. It’s in Ramsgate. Actually my father is the Principal. But I haven’t come from school, I’ve been two years at University College, London. I did a bit of rowing there, actually. And you?

Pollard King’s College School.

Jackson You play rugby, don’t you?

Pollard Yes. Not personally.

Jackson I prefer rugby football to Association rules. I wonder if the College turns out a strong side. I don’t count myself a serious cricketer though I can put in a useful knock on occasion. Field athletics is probably what I’ll concentrate on in the Easter term.

Pollard Ah. So long as it’s not trundling a hoop.

Jackson No, I’m a runner first and foremost, I suppose. The quarter-mile and the half-mile are my best distances.

Pollard So you’re keen on sport.

Jackson One is at Oxford to work, of course, but as the poet said – all work and no play …

Pollard (overlapping) Orandum est ut sit mens sana in corpore sano.

Jackson … makes Jack a dull boy.

Pollard I didn’t realize that the classics scholarship was open to university men.

Jackson Classics? No, that’s not me. I have the science scholarship.

Pollard (happily) Oh … Science! Sorry! How do you do?

Jackson I’m Jackson.

Pollard Pollard. Congratulations. That explains it.

Jackson What?

Pollard I don’t know. Yes, trochus comes into Ovid, or Horace somewhere, the Satires.

Housman joins.

Housman The Odes. Sorry. Odes Three, 24, ‘ludere doctior seu Graeco iubeas trocho’ – it’s where he’s saying everything’s gone to the dogs.

Pollard That’s it! Highborn young men can’t sit on a horse and are afraid to hunt, they’re better at playing with the Greek hoop!

Housman Actually, ‘trochos’ is Greek, it’s the Greek word for hoop, so when Horace uses ‘Graecus trochus’ it’s rather like saying ‘French chapeau’. I mean he’s laying it on thick, isn’t he?

Jackson Is he? What?

Housman Well, to a Roman, to call something Greek meant – very often – sissylike, or effeminate. In fact, a hoop, a trochos, was a favourite gift given by a Greek man to the boy he, you know, to his favourite boy.

Jackson Oh, beastliness, you mean?

Pollard This is Mr Jackson, by the way.

Housman How do you do, sir?

Jackson I say, I’m a freshman too, you know. Have you seen there’s a board where you put your name down? I’m going to try for the Torpids next term. Perhaps I’ll see you at the river.

Pollard (overlapping) – at dinner – river.

Jackson goes.

A science scholar.

Housman Seems quite decent, though.

Pollard I’m Pollard.

Housman Housman. We’re on the same staircase.

Pollard Oh, spiffing. Where were you at school?

Housman Bromsgrove. It’s in, well, Bromsgrove, in fact. It’s a place in Worcestershire.

Pollard I was at King’s College School – that’s in London.

Housman I’ve been to London. I went to the Albert Hall and the British Museum. The best thing was the Guards, though. You were right about Ovid, by the way. Trochus is in Ars. Am.

An Oxford garden, a river, a garden seat.

An invisible ‘croquet ball’ rolls on, followed by Pattison with a croquet mallet.

Pattison My young friends, I am very grieved to tell you that if you have come up to Oxford with the idea of getting knowledge, you must give that up at once. We have bought you, and we’re running you in two plates, Mods and the Finals.

Pattison The curriculum is designed on the idle plan that all of knowledge will be found inside the covers of four Latin and four Greek books, though not the same four each year.

Housman Thank you, sir.

Pattison A genuine love of learning is one of the two delinquencies which cause blindness and lead a young man to ruin.

Pollard/Housman (leaving) Yes, sir, thank you, sir.

Pattison Hopeless.

Pattison knocks his croquet ball off-stage and follows it.

Pater enters attended by a Balliol Student. The Student is handsome and debonair. Pater is short, unhandsome, a dandy: top hat, yellow gloves, blue cravat.

Pater Thank you for sending me your sonnet, dear boy. And also for your photograph, of course. But why do you always write poetry? Why don’t you write prose? Prose is so much more difficult.

Student No one has written the poetry I wish to write, Mr Pater, but you have already written the prose.

Pater That is charmingly said. I will look at your photograph more carefully when I get home.

They leave.

Ruskin and Jowett enter, playing croquet.

Ruskin I was seventeen when I came up to Oxford. That was in 1836, and the word ‘Aesthete’ was unknown. Aesthetics was newly arrived from Germany but there was no suggestion that it involved dressing up, as it might be the London Fire Brigade; nor that it was connected in some way with that excessive admiration for male physical beauty which conduced to the fall of Greece. It was not until the 1860s that moral degeneracy came under the baleful protection of artistic licence and advertised itself as aesthetic. Before that, unnatural behaviour was generally left behind at school, like football …

Jowett Alas, I was considered very beautiful at school. I had golden curls. The other boys called me Miss Jowett. How I dreaded that ghastly ritual! – the torment! – the humiliation! – my body ached from the indignities, I used to run away whenever the ball came near me …

As they leave.

No one now, I think, calls me Miss Jowett … or Mistress of Balliol.

Housman, Pollard and Jackson enter in a boat, Jackson rowing.

Housman False quantities in all around I see, yea we have been forsaken in the wilderness to gather grapes of thorns and figs of thistles.

Pollard That’s possibly why the College is named for John the Baptist.

Jackson John the Baptist was locusts and wild honey, actually, Pollard.

Pollard It’s the Baptist School of Hard Knocks. First the Wilderness, then the head on the platter.

Housman It was clear something was amiss from the day we matriculated. The statutes warned us against drinking, gambling and hoop-trundling but not a word about Jowett’s translation of Plato. The Regius Professor can’t even pronounce the Greek language and there is no one at Oxford to tell him.

Pollard Except you, Housman.

Housman I will take his secret to the grave, telling people I meet on the way. Betrayal is no sin if it’s whimsical.

Jackson We did the new pronunciation, you know. As an Englishman I never took to the speaking of it. Veni, vidi, vici … It was never natural to my mind.

Latin pronunciation: ‘wayny, weedy, weeky’.

Pollard That was Latin, actually, Jackson.

Jackson And ‘Wennus’ the Goddess of Love. I mean to say!

Pollard Perhaps I don’t make myself plain. Latin and Greek are two entirely separate languages spoken by distinct peoples living in different parts of the ancient world. Some inkling of this must have got through to you, Jackson, at the Vale Academy, Ramsgate, surely.

Housman But ‘“Wennus” the Goddess of Love’, for a man of Jackson’s venereal pursuits, is a strong objection to the new pronunciation – where is the chemistry in Wennus?

Jackson I know you and Pollard look down on science.

Pollard Is it a science? Ovid said it was an art.

Jackson Oh – love! You’re just ragging me because you’ve never kissed a girl.

Pollard Well, what’s it like, Jackson?

Jackson Kissing girls is not like science, nor is it like sport. It is the third thing when you thought there were only two.

Housman Da mi basia mille, deinde centum.

Pollard Catullus! Give me a thousand kisses, and then a hundred! Then another thousand, then a second hundred! – yes, Catullus is Jackson’s sort of poet.

Jackson How does it go? Is it suitable for sending to Miss Liddell as my own work?

Pollard That depends on which Miss Liddell. Does she go dum-di-di?

Jackson I very much doubt it. She’s the daughter of the Dean of Christ Church.

Pollard You misunderstand. She has to scan with Lesbia. All Catullus’s love poems are written to Lesbia, or about her. ‘Vivamus, mea Lesbia, atque amemus …’

Jackson I mean in English. Girls who kiss don’t know Latin.

Pollard Oh, in English. Come on, Housman. ‘Let us live, my Lesbia, and let us love, and value at one penny the murmurs of disapproving old men …’

Housman ‘And not give tuppence for the mutterence of old men’s tut-tutterence.’

Pollard He’s such a show-off.

Housman

‘Suns can set and rise again: when our brief light

is gone we sleep the sleep of perpetual night.

Give me a thousand kisses, and then a hundred more,

and then another thousand, and add five score …’

Jackson But what happens in the end?

Housman In the end they’re both dead and Catullus is set for Moderations. Nox est perpetua.

Pollard It’s not perpetual if he’s set for Mods.

Housman Is that Church of England?

Jackson Did they get married?

Pollard No. They loved, and quarrelled, and made up, and loved, and fought, and were true to each other and untrue. She made him the happiest man in the whole world and the most wretched, and after a few years she died, and then, when he was thirty, he died, too. But by that time Catullus had invented the love poem.

Jackson He invented it? Did he, Hous?

Pollard You don’t have to ask him. Like everything else, like clocks and trousers and algebra, the love poem had to be invented. After millenniums of sex and centuries of poetry, the love poem as understood by Shakespeare and Donne, and by Oxford undergraduates – the true-life confessions of the poet in love, immortalizing the mistress, who is actually the cause of the poem – that was invented in Rome in the first century before Christ.

Jackson Gosh.

Housman Basium is a point of interest. A kiss was always osculum until Catullus.

Pollard Now, Hous, concentrate – is that the point of interest in the kiss?

Housman Yes.

Pollard Pull on your right.

Jackson Do you want to take the oars?

Pollard No, you’re doing splendidly.

Jackson Hous hasn’t done any work since below Iffley.

Housman The nerve of it! Who brought us up from Hades?

They row out of sight.

The croquet game returns – Pattison, followed in series by Jowett, Pater and Ruskin. The game accounts for the entrances, actions and exits of Pattison, Pater, Jowett and Ruskin.

Pattison I was not quite seventeen when I first saw Oxford. That was in 1830 and Oxford was delightful then, not the overbuilt slum it has become. The town teems with people who have no business here, which is to say business is all they have. The University held off the London and Birmingham Railway until the forties, and I said at the time, ‘If the Birmingham train comes, can the London train be far behind?’

Pater I don’t think that can be quite right, Dr Pattison.

Jowett Posting ten miles to Steventon for the Paddington train was never anything to cherish. Personally, I thank God for the branch line, and hope His merciful bounty is not exhausted by changing at Didcot.

Ruskin When I am at Paddington I feel I am in hell.

Jowett You must not go about telling everyone, Dr Ruskin. It will not do for the moral education of Oxford undergraduates that the wages of sin may be no more than the sense of being stranded at one of the larger railway stations.

Ruskin To be morally educated is to realize that such would be a terrible price. Mechanical advance is the slack taken up of our failing humanity. Hell is very likely to be modernization infinitely extended. There is a rocky valley between Buxton and Bakewell where once you may have seen at first and last light the Muses dance for Apollo and heard the pan-pipes play. But its rocks were blasted away for the railway, and now every fool in Buxton can be at Bakewell in half an hour, and every fool in Bakewell at Buxton.

Pater (at croquet) First-class return.

Jowett Mind the gap.

Pattison Personally I am in favour of education but a university is not the place for it. A university exists to seek the meaning of life by the pursuit of scholarship.

Ruskin I have announced the meaning of life in my lectures. There is nothing beautiful which is not good, and nothing good which has no moral purpose. I had my students up at dawn building a flower-bordered road across a swamp at Ferry Hinksey. There was an Irish exquisite, a great slab of a youth with white hands and long poetical hair who said he was glad to say he had never seen a shovel, but I made him a navvy for one term and taught him that the work of one’s hands is the beginning of virtue. Then I went sketching to Venice and the road sank into the swamp. My protégé rose at noon to smoke cigarettes and read French novels, and Oxford reverted to a cockney watering-place for learning to row.

Housman and Pollard enter along the river bank,

Housman intent on an unseen boat race.

Housman Come on, St John’s!

Pollard Ruskin said, when he’s at Paddington he feels he is in hell – and this man Oscar Wilde said, ‘Ah, but –’

Housman ‘– when he’s in hell he’ll think he’s only at Paddington.’ It’ll be a pity if inversion is all he is known for. Row up, St John’s!

Pollard You hate sport.

Housman Keep the stroke!

Pollard Wilde is reckoned the wittiest man at Oxford. His rooms at Magdalen are said to be completely bare except for a lily in a blue vase.

Housman No furniture?

Pollard Well, of course there is furniture … I suppose there is furniture.

Housman Come on, St John’s!

Pollard He went to the Morrell’s ball in a Prince Rupert costume which he has absentmindedly put on every morning since, and has been seen wearing it in the High. Everyone is repeating his remark that he finds it harder and harder every day to live up to his blue china. Don’t you think that’s priceless?

Housman We have a blue china butterdish at Bromsgrove, we never take any notice of it.

Well rowed! Bad luck, St John’s!

Jowett I was eighteen when I came up to Oxford. That was in 1835, and Oxford was an utter disgrace. Education rarely interfered with the life of the University. Learning was carried on in nooks and corners, like Papism in an Elizabethan manor house. The fellows were socially negligible, and perfectly astonished by the historical process that had placed the teaching of undergraduates into the hands of amiable clergymen waiting for preferment to a country parsonage. I say nothing against the undergraduates, a debauched and indolent rabble as it happens. The great reform of the fifties laid the foundation of the educated class that has spread moral and social order to parts of the world where, to take one example, my Plato was formerly quite unknown.

Pattison The great reform made us into a cramming shop. The railway brings in the fools and takes them away with their tickets punched for the world outside.

Jowett The modern university exists by consent of the world outside. We must send out men fitted for that world. What better example can we show them than classical antiquity? Nowhere was the ideal of morality, art and social order realized more harmoniously than in Greece in the age of the great philosophers.

Ruskin Buggery apart.

Jowett Buggery apart.

Pater Actually, Italy in the late-fifteenth century … Nowhere was the ideal of art, morality and social order realized more harmoniously, morality and social order apart.

Ruskin The Medieval Gothic! The Medieval Gothic cathedrals which were the great engines of art, morality and social order!

Pattison (at croquet) Check. Play the advantage.

Pater I have been touched by the medieval but its moment has passed, and now I wouldn’t return the compliment with a barge-pole. As for arts-and-crafts, it is very well for the people; without it, Liberty’s would be at risk, in fact it would be closed, but the true Aesthetic spirit goes back to Florence, Venice, Rome – Japanese apart. One sees it plain in Michelangelo’s David – legs apart.* The blue of my very necktie declares that we are still living in that revolution whereby man regained possession of his nature and produced the Italian Tumescence.

Pattison Renaissance, surely. Deuce.

Pater On the frescoed walls of Santa Maria della Grazie and the painted ceiling of St Pancras –

Pattison Peter’s, surely. Leg-before unless I’m much mistaken.

Jackson comes, in rowing kit.

Housman Well rowed, Jackson! I’m afraid they had the measure of us.

Jackson Extraordinary thing. Fellow in velvet knickerbockers like something from the halls came up and said he wished to compliment me on my race. I replied with dignity, ‘Thank you, but although my first name happens to be Moses I am not Jewish and can take no merit from it.’ He said, ‘Allow me to do the jokes, it’s what I’m at Oxford for – I saw you in the Torpids and your left leg is a poem.’

Pollard What did you say?

Jackson Naturally, I asked him if he was a rowing man. He said he tried out for an oar in the Magdalen boat but couldn’t see the use of going backwards down to Iffley every evening so he gave it up and now plays no outdoor games at all, except dominoes: he has sometimes played dominoes outside French cafés. Do you know what I think he is?

Pollard What?

Jackson I think he’s one of those Aesthetes.

They go.

Ruskin Conscience, faith, disciplined restraint, fidelity to nature – all the Christian virtues that gave us the cathedral at Chartres, the paintings of Giotto, the poetry of Dante – have been tricked out in iridescent rags to catch the attention of the moment.

Pater In the young Raphael, in the sonnets of Michelangelo, in Correggio’s lily-bearer in the cathedral at Parma, and ever so faintly in my necktie, we feel the touch of a, what shall I say? –

Pattison Barge-pole?

Pater Barge-pole? … No … the touch of a refined and comely paganism that rescued beauty from the charnel house of the Christian conscience. The Renaissance teaches us that the book of knowledge is not to be learned by rote but is to be written anew in the ecstasy of living each moment for the moment’s sake. Success in life is to maintain this ecstasy, to burn always with this hard gem-like flame. Failure is to form habits. To burn with a gem-like flame is to capture the awareness of each moment; and for that moment only. To form habits is to be absent from those moments. How may we always be present for them? – to garner not the fruits of experience but experience itself? –

At a distance, getting no closer, Jackson is seen as a runner running towards us.

The game takes Ruskin and Pattison out.

… to catch at the exquisite passion, the strange flower, or art – or the face of one’s friend? For, not to do so in our short day of frost and sun is to sleep before evening. The conventional morality which requires of us the sacrifice of any one of those moments has no real claim on us. The love of art for art’s sake seeks nothing in return except the highest quality to the moments of your life, and simply for those moments’ sake.

Jowett Mr Pater, can you spare a moment?

Pater Certainly! As many as you like!

Jackson arrives out of breath. Housman meets him, holding a watch. Jackson sits exhausted on the seat. Housman has a home-made ‘laurel crown’. He crowns Jackson – a lighthearted gesture.

Housman One minute, fifty-eight seconds.

Jackson What …?

Housman One fifty-eight, exactly.

Jackson That’s nonsense.

Housman Or two fifty-eight.

Jackson That’s nonsense the other way. What was the first quarter?

Housman I’m afraid I forgot to look.

Jackson What were you doing?

Housman Watching you.

Jackson You duffer!

Housman Why can’t it be one fifty-eight?

Jackson The world record for the half is over two minutes.

Housman Oh, well … congratulations, Jackson.

Jackson What will become of you, Hous?

Jackson takes off the laurel and leaves it on the seat, as he leaves. Housman picks up the book.

Housman It has become of me.

Pater The story has been grossly exaggerated, it has, if you will, accrued grossness in the telling, but when all’s said and done, a letter signed ‘Yours lovingly’ –

Jowett Several letters, and addressed to an undergraduate.

Pater Several letters signed ‘Yours lovingly’ and addressed to an undergraduate –

Jowett Of Balliol.

Pater Even of Balliol, do not prove beastliness – would hardly support a suggestion of spooniness, in fact –

Jowett From a tutor, sir, a fellow not even of his own College, thanking him for a disgusting sonnet!

Pater You feel, in short, Dr Jowett, that I have overstepped the mark.

Jowett I feel, Mr Pater, that letters to an undergraduate signed ‘Yours lovingly’, thanking him for a sonnet on the honeyed mouth and lissome thighs of Ganymede, would be capable of a construction fatal to the ideals of higher learning even if the undergraduate in question were not colloquially known as the Balliol bugger.

Pater You astonish me.

Jowett The Balliol bugger, I am assured.

Pater No, no, I am astonished that you should take exception to an obviously Platonic enthusiasm.

Jowett A Platonic enthusiasm as far as Plato was concerned meant an enthusiasm of the kind that would empty the public schools and fill the prisons where it is not nipped in the bud. In my translation of the Phaedrus it required all my ingenuity to rephrase his depiction of paederastia into the affectionate regard as exists between an Englishman and his wife. Plato would have made the transposition himself if he had had the good fortune to be a Balliol man.

Pater And yet, Master, no amount of ingenuity can dispose of boy-love as the distinguishing feature of a society which we venerate as one of the most brilliant in the history of human culture, raised far above its neighbours in moral and mental distinction.

Jowett You are very kind but one undergraduate is hardly a distinguishing feature, and I have written to his father to remove him. (to Housman, who is arriving with a new book) Pack your bags, sir, and be gone! The canker that brought low the glory that was Greece shall not prevail over Balliol!

Pater (leaving, to Housman) It’s a long story, but there is a wash and it will all come out in it.

Housman I am Housman, sir, of St John’s.

Jowett Then I am at a loss to understand why I should be addressing you. Who is your tutor?

Housman I go to Mr Warren at Magdalen three times a week.

Jowett That must be it. Warren is a Balliol man, he has spoken of you, he believes you capable of great things.

Housman Really, sir?

Jowett If you can rid yourself of your levity and your cynicism, and find another way to dissimulate your Irish provincialism than by making affected remarks about your blue china and going about in plum-coloured velvet breeches, which you don’t, and cut your hair – you’re not him at all, are you? Never mind, what have you got there? Oh, Munro’s Catullus. I glanced at it in Blackwell’s. A great deal of Munro and precious little of Catullus. It’s amazing what people will pay four shillings and sixpence for. Is Catullus on your reading list?

Housman Yes, sir, ‘The Marriage of Peleus and Thetis’.

Jowett Catullus 64! Lord Leighton should paint that opening scene! The flower of the young men of Argos hot for the capture of the Golden Fleece, churning the waves with their blades of pine, the first ship ever to plough the ocean! ‘And the wild faces of the sea-nymphs emerged from the white foaming waters – emersere feri candenti e gurgite vultus aequoreae – staring in amazement at the sight – monstrum Nereides admirantes.’

Housman Yes, sir. Freti, actually, sir.

Jowett What?

Housman Munro concurs that feri is a mistake for freti, sir, because vultus must be accusative.

Jowett Concurs with whom?

Housman Concurs with, well, everybody.

Jowett Everybody but Catullus. The textual critics have spoken. Death to wild faces emerging in the nominative. Long live the transitive emersere raising up the accusative unqualified faces from the white foaming waters, of the freti, something watery like channel. Never mind that we already have so many watery words that the last thing we need is another – here we are: ‘freti for feri is an easy correction, as r, t, tr, rt are among the letters most frequently confounded in the manuscripts.’ Well, Munro is entitled to concur with everybody who amends the manuscripts of Catullus according to his taste and calls his taste his conjectures – it’s a futile business suitable to occupy the leisure of professors of Cambridge University. But you, sir, have not been put on earth with an Oxford scholarship so that you may bother your head with whether Catullus in such-and-such place wrote ut or et or aut or none of them or whether such-and-such line is spurious or corrupt or on the contrary an example of Catullus’s peculiar genius. You are here to take the ancient authors as they come from a reputable English printer, and to study them until you can write in the metre. If you cannot write Latin and Greek verse how can you hope to be of any use in the world?

Housman But isn’t it of use to establish what the ancient authors really wrote?

Jowett It would be on the whole desirable rather than undesirable and the job was pretty well done, where it could be done, by good scholars dead these hundred years and more. For the rest, certainty could only come from recovering the autograph. This morning I had cause to have typewritten an autograph letter I wrote to the father of a certain undergraduate. The copy as I received it asserted that the Master of Balliol had a solemn duty to stamp out unnatural mice. In other words, anyone with a secretary knows that what Catullus really wrote was already corrupt by the time it was copied twice, which was about the time of the first Roman invasion of Britain: and the earliest copy that has come down to us was written about 1,500 years after that. Think of all those secretaries! – corruption breeding corruption from papyrus to papyrus, and from the last disintegrating scrolls to the first new-fangled parchment books, with a thousand years of copying-out still to come, running the gauntlet of changing forms of script and spelling, and absence of punctuation – not to mention mildew and rats and fire and flood and Christian disapproval to the brink of extinction as what Catullus really wrote passed from scribe to scribe, this one drunk, that one sleepy, another without scruple, and of those sober, wide-awake and scrupulous, some ignorant of Latin and some, even worse, fancying themselves better Latinists than Catullus – until! – finally and at long last – mangled and tattered like a dog that has fought its way home, there falls across the threshold of the Italian Renaissance the sole surviving witness to thirty generations of carelessness and stupidity: the Verona Codex of Catullus; which was almost immediately lost again, but not before being copied with one last opportunity for error. And there you have the foundation of the poems of Catullus as they went to the printer for the first time, in Venice 400 years ago.

Housman Where, sir?

Jowett (pointing) In there.

Housman Do you mean, sir, that it’s here in Oxford?

Jowett Why, yes. That is why it is called the Codex Oxoniensis. Only recently was its importance recognized, by a German scholar who made the Oxoniensis the foundation of his edition of the poet. Mr Robinson Ellis of Trinity College discovered its existence several years before but, unluckily, not its importance, and his edition of Catullus has the singular distinction of vitiating itself by ignoring the discovery of its own editor.

Ellis enters as a child with a lollipop, on a scooter; but not dressed as a child.

Awfully hard cheese, Ellis! Ignoring your Oxoniensis!

Ellis Didn’t ignore it.

Jowett Did.

Ellis Didn’t.

Jowett Did.

Ellis Didn’t!

They continue thuswise as AEH and Charon pole into view on the river.

Jowett Did.

Ellis Didn’t.

Jowett (leaving) Did, did, did!

Ellis Didn’t! And anyway, Baehrens overvalued it, so there!

AEH That’s Bobby Ellis! He’s somewhat altered in demeanour, but the intellect is unmistakable.

Ellis Young man, they tell me you are an absolutely safe First. I am proposing to form a class next term to read the Monobiblos. The fee will be one pound.

Housman The Monobiblos?

AEH I’ve seen him before, too.

Ellis Dear me. Propertius Book One.

Housman Propertius.

Ellis The greatest of the Roman love elegists, and the most corrupt.

Housman Oh.

Ellis Only Catullus has a later text, but I would say Propertius is the more corrupt.

Housman Oh – corrupt. Yes. Thank you, sir.

They go.

AEH Do you know Propertius?

Charon You mean personally?

AEH I mean the poems.

Charon Ah. No, then. Here we are. Elysium.

AEH Elysium! Where else?! I was eighteen when I first saw Oxford, and Oxford was charming then, not the trippery emporium it has become. There were horse-buses at the station to meet the Birmingham train; and not a brick to be seen, before the Kinema and Kardomah. The Oxford of my dreams, re-dreamt. The desire to urinate, combined with a sense that it would not be a good idea, usually means we are asleep.

Charon Or in a boat. That happened to me once.

AEH Were you asleep?

Charon No, I was in a play.

AEH That needs thinking about.

Charon Aristophanes, The Frogs.

AEH You speak the truth. I saw you.

Charon I had that Dionysus in the back of my boat.

AEH You were very good.

Charon No, I was just in it. I was caught short. Good stuff, The Frogs, don’t you think?

AEH Not particularly. But it quotes from Aeschylus.

Charon Ah, now that was a play.

AEH What was?

Charon Aeschylus, Myrmidones. Do you know it?

AEH It didn’t survive; only the title and some fragments. I would join Sisyphus in Hades and gladly push my boulder up the slope if only, each time it rolled back down, I were given a line of Aeschylus.

Charon I think I can remember some of it.

AEH Oh my goodness.

Charon Give me a minute.

AEH Oh my Lord.

Charon Achilles is in his tent.

AEH Oh please don’t let it be a dream!

Charon The chorus is his clansmen, the Myrmidons.

AEH Yes.

Charon They tell him off for sulking in his –

AEH Tent, yes, but can you remember an actual line that Aeschylus wrote?

Charon I’m coming to it. First Achilles compares himself to an eagle hit by an arrow fledged with one of its own feathers, do you know that one?

AEH The words, the words.

Charon Achilles is in his –

AEH Tent.

Charon Tent – am I telling this or are you? – he’s playing dice with himself when news comes that Patroclus has been killed. Achilles goes mad, blaming him, you see, for being dead. Now for the line. ‘Does it mean nothing to you,’ he says, ‘the unblemished thighs I worshipped and the showers of kisses you had from me.’

AEH

Charon There you go.

AEH Yes, I see.

Charon No good?

AEH Very good. It’s one of the fragments that has come down to us. Also the metaphor of the eagle, but not Aeschylus’s own words, which I dare say you can’t recall.

Charon It’s maddening, isn’t it?

AEH Quite so. All is plain. I may as well wet the bed, the night nurse will change the sheets and tuck me up without reproach. They are very kind to me here in the Evelyn Nursing Home.

Jackson (off-stage) Housman!

Pollard (off-stage) Housman!

Charon Look alive, then! Get it?

AEH Indeed yes.

Charon I’ve got dozens of them like that.

AEH Perhaps next time.

Charon I’m afraid not.

AEH Ah yes. Where is thy sting?

Charon poles AEH to the shore.

Pollard (off-stage) Hous! – Picnic!

Jackson (off-stage) Locusts! Honey!

Housman enters with a pile of books which he puts down on the seat.

Housman I say, can I give you a hand?

AEH (to Charon) Who’s that?

Charon Who’s that, he says.

AEH (to Housman) Thank you!

Charon Dead on time.

Housman helps AEH ashore.

AEH Most opportune.

Charon Dead on time! – there’s no end to them! (He poles himself away.)

AEH Don’t mind him. What are you doing here, may one ask?

Housman Classics, sir. I’m studying for Greats.

AEH Are you? I did Greats, too. Of course, that was more than fifty years ago, when Oxford was still the sweet city of dreaming spires.

Housman It must have been delightful then.

AEH It was. I felt as if I had come up from the plains of Moab to the top of Mount Pisgah like Moses when the Lord showed him all the land of Judah unto the utmost sea.

Housman There’s a hill near our house where I live in Worcestershire which I and my brothers and sisters call Mount Pisgah. I used to climb it often, and look out towards Wales, to what I thought was a kind of Promised Land, though it was only the Clee Hills really – Shropshire was our western horizon.

AEH Oh … excellent. You are …

Housman Housman, sir, of St John’s.

AEH Well, this is an unexpected development. Where can we sit down before philosophy finds us out. I’m not as young as I was. Whereas you, of course, are.

They sit.

Classical studies, eh?

Housman Yes, sir.

AEH You are to be a rounded man, fit for the world, a man of taste and moral sense.

Housman Yes, sir.

AEH Science for our material improvement, classics for our inner nature. The beautiful and the good. Culture. Virtue. The ideas and moral influence of the ancient philosophers.

Housman Yes, sir.

AEH Humbug.

Housman Oh.

AEH Looking about you, does it appear to you that the classical fellows are the superior in sense, morality, taste, or even amiability, to the scientists?

Housman I’m acquainted with only one person in the Science School, and he is the finest man I know.

AEH And he knows more than the ancient philosophers.

Housman (Oh –!)

AEH They made the best use of the knowledge they had. They were the best minds. The French are the best cooks, and during the Siege of Paris I’m sure rats never tasted better, but that is no reason to continue eating rat now that coq au vin is available. The only reason to consider what the ancient philosophers meant about anything is if it’s relevant to settling corrupt or disputed passages in the text. With the poets there may be other reasons for reading them; I wouldn’t discount it – it may even improve your inner nature, if the miraculous collusion of sound and sense in, let us say, certain poems by Horace, teaches humility in regard to adding to the store of available literature poems by, let us say, yourself. But the effect is not widespread. Are these your books?

Housman Yes, sir.

AEH What have we here? (He looks at Housman’s books, reading the spines. He never opens them.) Propertius! And … Propertius! And, of course, Propertius.

Housman (eagerly) Do you know him?

AEH No, not as yet.

Housman He’s difficult – tangled-up thoughts, or, anyway, tangled-up Latin –

AEH Oh – know him.

Housman – if you can believe the manuscripts – which you can’t because they all come from the same one, and that was about as far removed from Propertius as we are from Alfred burning the cakes! He just scraped through to the invention of printing – a miracle! – the first of the Roman love elegists.

AEH Not the first, I think, strictly speaking.

Housman Oh, yes. Really and truly. Catullus was earlier but he used all sorts of metres for his Lesbia poems.

AEH Ah.

Housman Propertius’s mistress was called Cynthia – ‘Cynthia who first took me captive with her eyes.’

AEH Cynthia prima suis miserum me cepit ocellis. You mustn’t forget miserum.

Housman Yes – poor me. You do know him.

AEH Oh, yes. When I was a young man at Oxford my edition of Propertius was going to replace all its forerunners and require no successor.

Housman Wouldn’t that be something! I have been thinking of it, too. You see, Propertius is so corrupt (that) it seems to me, even today, here is a poet on which the work has not been done. All those editors!, each with his own Propertius, right up to Baehrens hot from the press! – and still (there’s) the feeling that between the natural chaos of his writing and the whole hit-or-miss of the manuscripts, nobody has got the text anywhere near right. Baehrens should make everyone obsolete – isn’t that why one edits Propertius? It’s certainly why I would edit Propertius! – but one has hardly settled down with Baehrens before one is jolted out of one’s chair by something like cunctas in one-one-five.

AEH Yes, cunctas for castas is intolerable.

Housman Well, exactly! – and he’s Baehrens, who found the Catullus Oxoniensis in the Bodleian library!

AEH Baehrens is overenamoured with the manuscripts overlooked by everyone but himself. He’s only human, and that’s an impediment to editing a classic. To defend the credit of a scribe he’ll impute any idiocy to a poet. His conjectures, on the other hand, are despicable trifling or barbarous depravations; yet on the whole his vanity and arrogance have deprived Baehrens of the esteem his Propertius is due.

Housman (confused) Oh … so is he good or bad?

AEH On that, you’ll have to ask his mother. (He picks up the next book.) And here is Paley with et for aut in one-one-twenty-five. He overestimates Propertius as a poet, in my opinion, yet he has no scruple in making Propertius pray that Cynthia may love him and also that he may cease to love Cynthia! (Puts the book aside.) Some of it may be read without mirth or disgust.

Housman (shocked) Paley?!

AEH (next book) And Palmer. Palmer is a different case. He is more singularly and eminently gifted by nature than any English Latinist since Markland.

Housman (eagerly) Really? Palmer, then?

AEH With all his genius, in precision of thought and stability of judgement many excel him.

Housman Oh.

AEH Munro most of all.

Housman Oh, yes – Munro!

AEH And Munro you wouldn’t rely on for settling a text. But Palmer has no intellectual power. Sustained thought is beyond him, so he shuns it.

Housman But I thought you said –

AEH He trusts to his felicity of instinct. When that fails him, no one can defend more stubbornly a plain corruption, or advocate more confidently an incredible conjecture, and to these defects he adds a calamitous propensity to reckless assertion.

Housman Oh! So, really, Palmer …

AEH (next book) Oh, yes. A liar and a slave. (next book) And him: I could teach a dog to edit Propertius like him. (next book) Oh, dear … well, his idea of editing a text is to change a letter or two and see what happens. If what happens can by the warmest goodwill be mistaken for sense and grammar he calls it an emendation. This is not scholarship, it is not even a sport, like hopscotch or marbles, which requires a degree of skill. It is simply a pastime, like leaning against a wall and spitting.

Housman But that’s Mr Ellis! – I went to him for Propertius!

AEH Indeed, yes, I saw him. I thought he looked well, dangerously well. (next book) Ah! – Mueller! (next book) And Haupt! (next book) Rosberg! Really there’s no need for you to read anything published in German in the last fifty years. Or the next fifty.

AEH picks up Housman’s notebook casually. Housman takes it from him, a little awkwardly.

Housman Oh – that’s only …

AEH Oh – of course. You do write poetry.

Housman Well, I’ve written poems, as one does, you know …

AEH One does.

Housman … for the poetry prize at school – quite speakable, I think –

AEH Good for you, mine were quite unspeakable.

Housman Actually, I was thinking of going in for the Newdigate – I thought the poem that won it last year was not so – how may one put it?

AEH Not such a poem as to suggest that your attempt would be a piece of impudence.

Housman But I don’t know, I don’t feel enough of a swell to carry off the Newdigate. Oscar Wilde of Magdalen, who went down with the Newdigate and a First in Greats, used to have tea with Ruskin. Pater used to have tea with him, in his rooms, and talk of lilies perhaps, and Michelangelo, and the French novel. The year before Wilde, it was won by a Balliol man who sent poems to Pater in the manner of the early Greek lyrics treating of matters that get you sacked at Oxford, and was duly sacked by Dr Jowett, which is rather grand behaviour in itself and almost excusable as a miscalculation of the limits of the Aesthetic. How am I to leave my mark?, a monument more lasting than bronze as Horace boasted, higher than the pyramids of kings, unyielding to wind and weather and the passage of time?

AEH Do you mean as a poet or a scholar?

AEH I think it helps to mind.

Housman Can’t one be both?

AEH No. Not of the first rank. Poetical feelings are a peril to scholarship. There are always poetical people ready to protest that a corrrupt line is exquisite. Exquisite to whom? The Romans were foreigners writing for foreigners two millenniums ago; and for people whose gods we find quaint, whose savagery we abominate, whose private habits we don’t like to talk about, but whose idea of what is exquisite is, we flatter ourselves, mysteriously identical with ours.

Housman But it is, isn’t it? We catch our breath at the places where the breath was always caught. The poet writes to his mistress how she’s killed his love – ‘fallen like a flower at the field’s edge where the plough touched it and passed on by’. He answers a friend’s letter – ‘so you won’t think your letter got forgotten like a lover’s apple forgotten in a good girl’s lap till she jumps up for her mother and spills it to the floor blushing crimson over her sorry face’. Two thousand years in the tick of a clock – oh, forgive me, I …

AEH No (need), we’re never too old to learn.

Housman I could weep when I think how nearly lost it was, that apple, and that flower, lying among the rubbish under a wine-vat, the last, corrupt, copy of Catullus left alive in the wreck of ancient literature. It’s a cry that cannot be ignored. Do you know Munro?

AEH I corresponded with him once.

Housman I’m going to write to him. Do you think he’d send me his photograph?

AEH No. What a strange thing is a young man. You had better be a poet. Literary enthusiasm never made a scholar, and unmade many. Taste is not knowledge. A scholar’s business is to add to what is known. That is all. But it is capable of giving the very greatest satisfaction, because knowledge is good. It does not have to look good or sound good or even do good. It is good just by being knowledge. And the only thing that makes it knowledge is that it is true. You can’t have too much of it and there is no little too little to be worth having. There is truth and falsehood in a comma. In your text of ‘The Marriage of Peleus and Thetis’, Catullus says that Peleus is the protector of the power of Emathia: Emathiae tutamen opis, comma, carissime nato: how can Peleus be carissime nato, most dear to his son, when his son has not yet been born?

Housman I don’t know.

AEH To be a scholar is to strike your finger on the page and say, ‘Thou ailest here, and here.’

Housman The comma has got itself in the wrong place, hasn’t it?, because there aren’t any commas in the Oxoniensis, any more than there are capital letters – which is the other thing –

AEH Not now, nurse, let him finish.

Housman So opis isn’t power with a small ‘o’, it’s the genitive of Ops who was the mother of Jupiter. Everything comes clear when you put the comma back one place.

AEH Emathiae tutamen, comma, Opis with a capital ‘O’, carissime nato. Protector of Emathia, most dear to the son of Ops.

Housman Is that right?

AEH Oh, yes. It’s right because it’s true – Peleus, the protector of Emathia, was most dear to Jupiter the son of Ops. By taking out a comma and putting it back in a different place, sense is made out of nonsense in a poem that has been read continuously since it was first misprinted four hundred years ago. A small victory over ignorance and error. A scrap of knowledge to add to our stock. What does this remind you of? Science, of course. Textual criticism is a science whose subject is literature, as botany is the science of flowers and zoology of animals and geology of rocks. Flowers, animals and rocks being the work of nature, their sciences are exact sciences, and must answer to the authority of what can be seen and measured. Literature, however, being the work of the human mind with all its frailty and aberration, and of human fingers which make mistakes, the science of textual criticism must aim for degrees of likelihood, and the only authority it might answer to is an author who has been dead for hundreds or thousands of years. But it is a science none the less, not a sacred mystery. Reason and common sense, a congenial intimacy with the author, a comprehensive familiarity with the language, a knowledge of ancient script for those fallible fingers, concentration, integrity, mother wit and repression of self-will – these are a good start for the textual critic. In other words, almost anybody can be a botanist or a zoologist. Textual criticism is the crown and summit of scholarship. Most people, though not enough, find it dry and dull, but it is the only reason for existence for a Latin professor. I tell you this because you would not know it from the way it is conducted in the English universities. The fudge and flim-flam, the hocus-pocus and plain dishonesty that parade as scholarship in the journals would excite the professional admiration of a hawker of patent medicines. In the German universities the situation is different. Most German scholars I would put up for the Institute of Mechanics; the remainder, the Institute of Statisticians. Except for Wilamowitz who is the greatest European scholar since Richard Bentley. There are people who say that I am but they would not know it if I were. Wilamowitz, I should add, is dead. Or will be. Or will have been dead. I think it must be time for my tablet, it orders my tenses. The future perfect I have always regarded as an oxymoron. I wouldn’t worry so much about your monument, if I were you. If I had my time again, I would pay more regard to those poems of Horace which tell you you will not have your time again. Life is brief and death kicks at the door impartially. Who knows how many tomorrows the gods will grant us? Now is the time, when you are young, to deck your hair with myrtle, drink the best of the wine, pluck the fruit. Seasons and moons renew themselves but neither noble name nor eloquence, no, nor righteous deeds will restore us. Night holds Hippolytus the pure of stain, Diana steads him nothing, he must stay; and Theseus leaves Pirithous in the chain the love of comrades cannot take away.

Housman What is that?

AEH A lapse.

Housman It’s ‘Diffugere nives’. Nec Lethaea valet Theseus abrumpere caro vincula Pirithoo. And Theseus has not the strength to break the Lethean bonds of his beloved Pirithous.

AEH Your translation is closer.

Housman Were they comrades – Theseus and Pirithous?

AEH (Yes), companions in adventure.

Housman Companions in adventure! There is something to stir the soul! Was there ever a love like the love of comrades ready to lay down their lives for each other?

AEH Oh, dear.

Housman I don’t mean spooniness, you know.

AEH Oh – not the love of comrades that gets you sacked at Oxford –

Housman (No! –)

AEH – not as in the lyric poets – ‘when thou art kind I spend the day like a god: when thy face is turned away, it is very dark with me’ –

Housman No – I mean friendship – virtue – like the Greek heroes.

AEH The Greek heroes – of course.

Housman The Argonauts … Achilles and Patroclus …

AEH Oh, yes, Achilles would get his Blue for single combat. Jason and the Argonauts would make an impression on Eights Week.

Housman Is it something to be made fun of, then?

AEH No. No.

Housman Oh, I know very well there are things not spoken of foursquare at Oxford. The passion for truth is the faintest of all human passions. In the translation of Tibullus in my College library, the he loved by the poet is turned into a she: and then when you come to the bit where this ‘she’ goes off with somebody’s wife, the translator is equal to the crisis – he leaves it out. Horace must have been a god when he wrote ‘Diffugere nives’ – the snows fled, and the seasons rolling round each year but for us, when we’ve had our turn, it’s over! – you can’t order words in English to get near it –

AEH

But oh, whate’er the sky-led seasons mar,

Moon upon moon rebuilds it with her beams:

Come we where Tullus and where Ancus are,

And good Aeneas, we are dust and dreams.

Housman (cheerfully) – yes, it’s hopeless, isn’t it? – one can only fall dumb, caught between your life that’s gone and going! Then turn a few pages back, and Horace is in tears over some athlete, running after him in his dreams, across the Field of Mars and into the rolling waves of the Tiber! – … Horace!, who has lots of girls in his poems; and that’s tame compared to Catullus – he’s madly in love with Lesbia, and in between – well, the least of it is stealing kisses from – frankly – a boy who’d still be in the junior dorm at Bromsgrove.

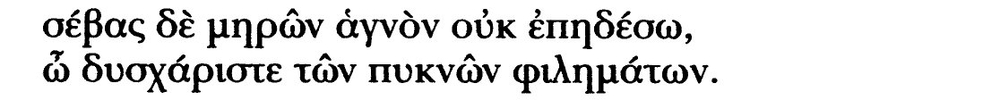

AEH Catullus 99 – vester for tuus is the point of interest there.

Housman No, it isn’t!

AEH I’m sorry.

Housman The point of interest is – what is virtue?, what is the good and the beautiful really and truly?

AEH notices the laurel on the seat. He picks it up, negligently.

AEH You think there is an answer: the lost autograph copy of life’s meaning, which we might recover from the corruptions that have made it nonsense. But if there is no such copy, really and truly there is no answer. It’s all in the timing. In Homer, Achilles and Patroclus were comrades, brave and pure of stain. Centuries later in a play now lost, Aeschylus brought in Eros, which I suppose we may translate as extreme spooniness; showers of kisses, and unblemished thighs. Sophocles, too; he wrote The Loves of Achilles: more spooniness than you’d find in a cutlery drawer, I shouldn’t wonder. Also lost.

Housman How is it known, if the plays were lost?

AEH They were mentioned by critics.

Housman There were critics?

AEH Naturally – it was the cradle of democracy. Euripides wrote a Pirithous, the last copy having passed through the intestines of an unknown rat probably a thousand years ago if it wasn’t burned by bishops – the Church’s idea of the good and the beautiful excludes sexual aberration, apart from chastity, I suppose because it’s the rarest. What is this? (He holds up the laurel crown.)

Housman It’s actually mine.

AEH You’d better take it, then.

To be the fastest runner, the strongest wrestler, the best at throwing the javelin – this was virtue when Horace in his dreams ran after Ligurinus across the Field of Mars, and Ligurinus didn’t lose his virtue by being caught. Virtue was practical: the athletic field was named after the god of war. If only an army should be made up of lovers and their loves! – that’s not me, that’s Plato, or rather Phaedrus in the Master of Balliol’s nimble translation: ‘although a mere handful, they would overcome the world, for each would rather die a thousand deaths than be seen by his beloved to abandon his post or throw away his arms, the veriest coward would be inspired by love’. Oh, one can sneer – the sophistry of dirty old men ogling beautiful young ones; then as now, ideals become debased. But there was such an army, a hundred and fifty pairs of lovers, the Sacred Band of Theban youths, and they were never beaten till Greek liberty died for good at the battle of Chaeronea. At the end of that day, says Plutarch, the victorious Philip of Macedon went forth to view the slain, and when he came to that place where the three hundred fought and lay dead together, he wondered, and understanding that it was the band of lovers, he shed tears and said, whoever suspects baseness in anything these men did, let him perish.

Housman I would be such a friend to someone.

AEH To dream of taking the sword in the breast, the bullet in the brain –

Housman I would.

AEH – and wake up to find the world goes wretchedly on and you will die of age and not of pain.

Housman (Well –)

AEH But lay down your life for your comrade – good lad! – lay it down like a doormat –

Housman (Oh –!)

AEH Lay it down like a card on a card-table for a kind word and a smile – lay it down like a bottle of the best to drink when your damnfool life is all but done: any more laying-downs we can think of? – oh, above all – above all – lay down your life like a pack on the roadside though your days of march are numbered and end with the grave. Love will not be deflected from its mischief by being called comradeship or anything else.

Housman I don’t know what love is.

AEH Oh, but you do. In the Dark Ages, in Macedonia, in the last guttering light from classical antiquity, a man copied out bits from old books for his young son, whose name was Septimius; so we have one sentence from The Loves of Achilles. Love, said Sophocles, is like the ice held in the hand by children. A piece of ice held fast in the fist. I wish I could help you, but it’s not in my gift.

Housman Love it is, then, and I will make the best of it. I’m sorry that it made you unhappy, but it’s not my fault, and it can’t be made good by unhappiness in another. Will you shake hands?

AEH Gladly. (He shakes Housman’s offered hand.)

Housman What happened to Theseus and Pirithous in the end?

AEH That was the end – their last adventure was down to Hades and they were caught, bound in invisible chains. Theseus was rescued finally but he had to leave his friend behind. In the chain the love of comrades cannot take away.

Housman That’s not right for abrumpere. If it were me I’d have put ‘break away’.

AEH If it were you, you wouldn’t win the Newdigate either.

Housman Oh, I don’t expect I will. The subject this year is from Catullus – the lament for the Golden Age when the gods still came down to visit us, before we went to the bad.

AEH An excellent topic for a poem. False nostalgia. Ruskin said you could see the Muses dance for Apollo in Derbyshire before the railways.

Housman Where did he say that?

AEH (points) There.

Is there a chamberpot under this seat?

Housman A …? No.

AEH Well, it probably isn’t a good idea.

We’re always living in someone’s golden age, it turns out: even Ruskin who takes it all so hard. A hard nut: he looks hard at everything he looks at, and everything he looks at looks hard back at him, it would drive anybody mad. In no time at all, life is like a street accident, with Ruskin raving for doctors, diverting the traffic and calling for laws to control the highway – and that’s just his art criticism.

Housman I heard Ruskin lecture in my first term. Painters belayed on every side.

AEH I think we’re in danger of going round again.

He stands up. Housman picks up his books. Pater and the Balliol Student enter as before.

Pater That is charmingly said. I will look at your photograph more carefully when I get home.

They leave.

AEH Yes, we are.

Pater doesn’t meddle, minds his business, steps aside. When he looks at a thing, it melts: tone, resonance, complexity, a moment’s rapture and for him alone. Life is not there to be understood, only endured and ameliorated. You’ll be all right one way or the other. I was an absolutely safe First, too.

Housman Didn’t you get it?

AEH No. Nor a Second, nor a Third, nor even a pass degree.

Housman You were ploughed?

AEH Yes.

Housman But how?

AEH That’s what they all wanted to know.

Housman Oh …

Jackson (off-stage) Housman!

Pollard (off-stage) Housman!

Housman What happened after that?

AEH I became a clerk and lived in lodgings in Bayswater.

Pollard (off-stage) Hous! Picnic!

Jackson (off-stage) Locusts! Honey!

Housman I’m sorry, they’re calling me. Did you finish your Propertius?

AEH No.

Housman Have you still got it?

AEH Oh, yes. It’s in a box of papers I’ve arranged to be burned when I’m dead.

Jackson and Pollard arrive in the boat.

Housman (to the boat) I’m here.

AEH Mo …!

Pollard It’s time to go.

Housman goes to the boat and gets in.

AEH I would have died for you but I never had the luck!

Housman Where are we going?

Pollard Hades. I’ve brought my Plato – will you con him with me? –

Housman I haven’t looked at it. Plato is useless to explain anything except what Plato thought.

Jackson Why study him, then?

Pollard We study the ancient authors to draw lessons for our age.

Housman That’s all humbug.

Pollard Is it? So it is. We study the ancient authors to get a First and a life of learned ease.

Housman We need science to explain the world. Jackson knows more than Plato. The only reason to consider what Plato meant about anything is if it’s relevant to settling the text. Which is classical scholarship, which is a science, the science of textual criticism, Jackson – we will be scientists together. I mean we will both be scientists. Pollard will be what passes as a classical scholar at Oxford, which is to be a literary critic in dead languages.

Pollard I say, did you see in the Sketch – Oscar Wilde’s latest? ‘Oh, I have worked hard all day – in the morning I put in a comma, and in the afternoon I took it out again!’ Isn’t that priceless?

Housman Why?

Pollard What?

Housman Oh, I see. It was a joke, you mean?

Pollard Oh – really, Housman!

The boat takes them away.

Housman tosses the laurel wreath on the water.

Pull on your right, Jackson.

Jackson Do you want to take the oars?

AEH Parce, precor, precor. Odes Four, one. Ah me, Venus, you old bawd. Where were we? Oh! – we’re all here. Good. Open your Horace. Book Four, Ode One, a prayer to the Goddess of Love:

Intermissa, Venus, diu

rursus bella moves? Parce precor, precor!

– mercy, I pray, I pray!, or perhaps better: spare me, I beg you, I beg you! – the very words I spoke when I saw that Mr Fry was determined that bella is the adjective and very likely to mean beautiful, and that as eggs go with bacon it goes with Venus.

Intermissa Venus diu

rursus bellet moves?

Beautiful Venus having been interrupted do you move again?, he has Horace enquire in a rare moment of imbecility, and Horace is dead as we will all be dead but while I live I will report his cause aright. It’s war, Mr Fry!, and so is bella. Venus do you move war?, set in motion war, shall we say?, or start up the war, or better: Venus are you calling me to arms, rursus, again, diu, after a long time, intermissa, having been interrupted, or suspended if you like, and what is it that has been suspended? Two centuries ago Bentley read intermissa with bella, war having been suspended, not Venus, Mr Fry, and – yes – Mr Carsen – and also Miss Frobisher, good morning, you’ll forgive us for starting without you – and now all is clear, is it not? Ten years after announcing in Book Three that he was giving up love, the poet feels desire stirring once more and begs for mercy: ‘Venus, are you calling me to arms again after this long time of truce? Spare me, I beg you, I beg you!’ Miss Frobisher smiles, with little cause that I know of. If Jesus of Nazareth had had before him the example of Miss Frobisher getting through the Latin degree papers of the London University Examinations Board he wouldn’t have had to fall back on camels and the eyes of needles, and Miss Frobisher’s name would be a delightful surprise to encounter in Matthew, Chapter 19; as would, even more surprisingly, the London University Examinations Board. Your name is not Miss Frobisher? What is your name? Miss Burton. I’m very sorry. I stand corrected. If Jesus of Nazareth had had before him the example of Miss Burton getting through the … Oh, dear, I hope it is not I who have made you cry. You don’t mind? You don’t mind when I make you cry? Oh, Miss Burton, you must try to mind a little. Life is in the minding. Here is Horace at the age of fifty pretending not to mind, verse 29, me nec femina nec puer, iam nec spes animi eredula mutui – where’s the verb? anyone? iuvat, thank you, it delights me not, what doesn’t? – neither woman nor boy, nor the spes credula, the credulous hope, animi mutui – the trusting hope of love returned, nec, nor, that’s four necs and a fifth to come before the ‘but’, that’s why we call it poetry – nec certare iuvat mero – yes, to compete in wine, that’ll do for the moment, and nec – what? – nec vincire novis tempora floribus, rendered by Mr Howard as to tie new flowers to my head, Tennyson would hang himself – never mind, here is Horace not minding: I take no pleasure in woman or boy, nor the trusting hope of love returned, nor matching drink for drink, nor binding fresh-cut flowers around my brow – but – sed – cur heu, Ligurine, cur –

Jackson is seen as a runner running towards us from the dark, getting no closer.

– but why, Ligurinus, alas why this unaccustomed tear trickling down my cheek? – why does my glib tongue stumble to silence as I speak? At night I hold you fast in my dreams, I run after you across the Field of Mars, I follow you into the tumbling waters, and you show no pity.

Blackout.

*For this deplorable image the author gratefully acknowledges the actor playing Pater, Robin Soans.