5

How Creditor Rescue and Housing Policy Combined with Regulation to Blow Up the Housing Market

The proximate cause of the housing market’s collapse was the same proximate cause of the financial market’s destruction—too much leverage, too much borrowed money. Just as a highly leveraged investment bank risks insolvency if the value of its assets declines by a small amount, so too does a homeowner.

The buyer of a house who puts 3 percent down and borrows the rest is like the poker player. Being able to buy a house with only 3 percent down, or ideally even less, is a wonderful opportunity for the buyer to make a highly leveraged investment. With little skin in the game, the buyer is willing to take on a lot more risk when buying a house than if she had to put up 20 percent. And for many potential homebuyers, a low down payment is the only way to sit at the table at all.

When prices are rising, buying a house with little or no money down seems like a pretty good deal. Let’s say the house is in California, and the price of the house is $200,000. For $6,000 (3 percent down), the buyer has a stake in an asset that has been appreciating in some markets in some years at 20 percent. If this trend continues, a year from now, the house will be worth $40,000 more than she paid for it. The buyer will have seen a more than six-fold increase in her investment.

What is the downside risk? The downside risk is that housing prices level off or go down. If housing prices do go down a lot, the buyer could lose her $6,000, and she may also lose her house or find herself making monthly payments on an asset that is declining in value and therefore a very bad investment. This is why many homebuyers are currently defaulting on their mortgages and forfeiting any equity they once had in the house. In some states, in the case of default, the lender could go after her other assets as well, but in a lot of states—including California and Arizona, for example—the loan is what is called “non-recourse”—the lender can foreclose on the house and get whatever the house is worth but nothing else. Failing to pay the mortgage and losing your house is embarrassing and inconvenient, and, if you have a good credit rating, it will hurt even more. But the appeal of this deal to many buyers is clear, particularly when housing prices have been rising year after year after year.

The opportunity to borrow money with a 3 percent down payment has three effects on the housing market:

These circumstances all push up the demand for housing. And, of course, if housing prices ever fall, these loans will very quickly be underwater (meaning that the homeowner will owe more on the home than it is currently worth). A small decrease in housing values will cause a homeowner who put 3 percent down to have negative equity much quicker than a buyer who put 20 percent down. With a zero-down loan, the effects are even stronger. But in the early 2000s, a low down payment loan was like a lottery ticket with an unusually good chance of paying off. A zero-down loan was even better. And some loans not only didn’t require a down payment, but also covered closing costs.

Changes in tax policy sweetened the deal. The Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 made the first $250,000 ($500,000 for married couples) of capital gains from the sale of a primary residence tax exempt.2 Sellers no longer had to roll the profits over into a new purchase of equal or greater value. The act even allowed the capital gains on a second home, a pure investment, to be tax-free as long as you lived in that house for two of the previous five years. This tax policy change increased the value of the lottery ticket.

The cost of the lottery ticket depended on interest rates. In 2001, worried about deflation and recession and the stock market, Alan Greenspan lowered the federal funds rate (the rate at which banks can borrow money from each other) to its lowest level in forty years and kept it there for about three years.3 During this time, the rate on fixed-rate mortgages was falling, but the rate on adjustable rate mortgages, a short-term interest rate, fell even more, widening the gap between the two. Adjustable rate mortgages grew in popularity as a result.4

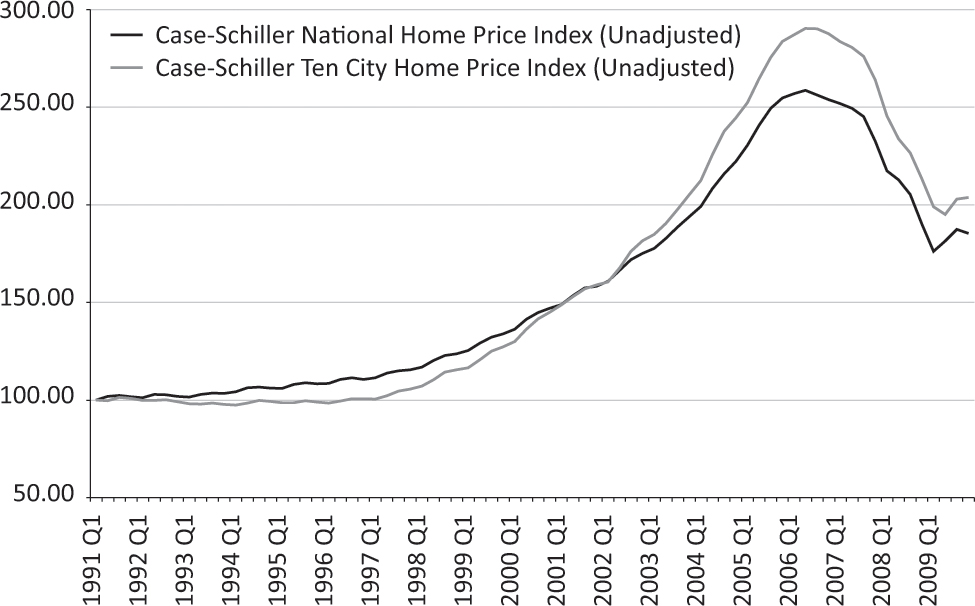

Figure 2. S&P/Case-Shiller House Price Indices, 1991–2009 (1991 Q1 = 100)

Source: Author’s calculations based on data presented in Scott Frame, Andreas Lehnert, and Ned Prescott, “A Snapshot of Mortgage Conditions with an Emphasis on Subprime Mortgage Performance,” paper presented to the Federal Reserve’s Home Mortgage Initiatives Coordinating Committee, April 27, 2008, http://federalreserveonline.org/pdf/MF_Knowledge_Snapshot-082708.pdf.

The falling interest rates, particularly on adjustable rate mortgages, meant that the price of the lottery ticket was falling dramatically. And as housing prices continued to rise, the probability of winning appeared to be going up (see figure 2). The upside potential was large. The downside risk was very small—mainly the monthly mortgage payment, which was offset by the advantage of being able to live in the house. Who wouldn’t want to invest in an asset that has a likely tax-free capital gain, that the buyer can enjoy in the meantime by living in it, and that she can own without using any of her own money? By 2005, 43 percent of first-time buyers were putting no money down, and 68 percent were putting down less than 10 percent.5

Incredibly, the buyer could even control how much the ticket cost. In a 2006 speech, Fannie Mae CEO Daniel Mudd outlined how monthly loan payments could differ when buying a $425,000 house, the average value of a house in the Washington, DC, area at the time:

In 2005, the average house in the Washington, DC, area grew in value by about 24 percent.7 For the average house bought for $425,000, that’s a gain of more than $100,000. The annual payment of that option adjustable rate mortgage was $15,000. That’s a pretty cheap lottery ticket for a chance to win $100,000 if prices rise in 2006 by the same amount as the year before. The buyer is paying less than she would in rent, and on top of that, she has a chance to win $100,000. Why wouldn’t a person with limited wealth want to get into that game? Why wouldn’t a person with lots of wealth?

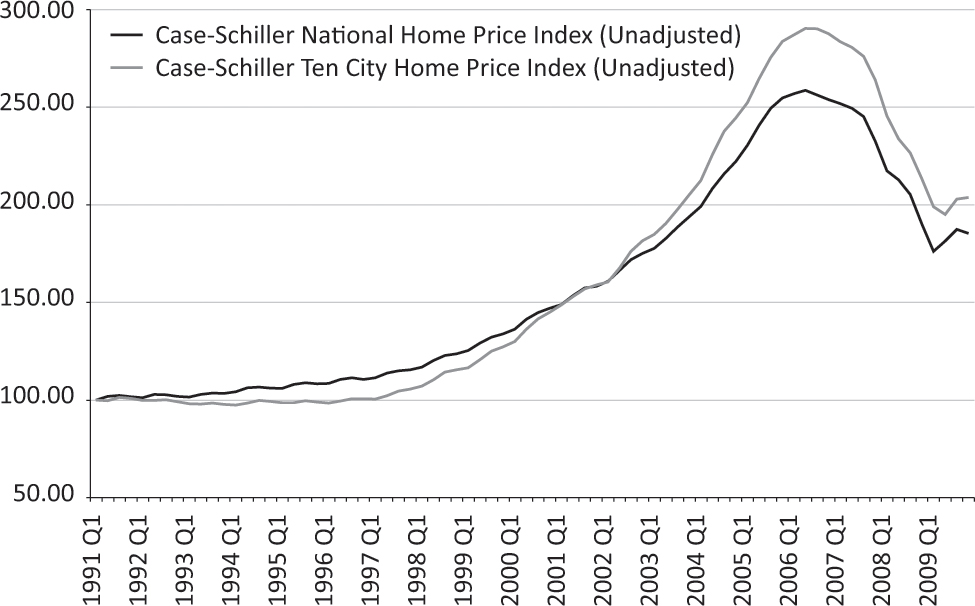

Figure 3. Issuance of Mortgage-Backed Securities, 1985–2009 (in billions of dollars)

Source: Author’s calculations based on data from Inside Mortgage Finance.

It’s obvious why buyers liked buying houses with little or no money down and the impact that opportunity had on the price of housing, but why would anyone lend money to buyers who had so little money of their own in a transaction? It’s the same question we asked earlier at the poker table. Why would anyone finance risky bets knowing that the bettor has so little skin in the game?

There are two reasons you might lend a lot of money to someone with no money of their own in the transaction. If home prices are rising and have been for a while, you might be pretty confident that they’ll continue to rise. In that case, the borrower will have equity in the home at the end of the year, and the chance of default will be smaller than it would normally be. You might take a chance and lend the money. But it’s a chance.

This is one explanation for the explosive growth of mortgage securitization—no one thought housing prices would go down (see figure 3). That could be. Yet, historically, nobody made loans where the borrower put little or no money down.

The second reason is that you will be very comfortable lending the money if you know you can sell the loan to someone else. Who is that someone? Between 1998 and 2003, the most frequent buyers of loans were the government-sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Fannie and Freddie bought those loans with borrowed money. Fannie and Freddie were able to borrow the money because the lenders were confident that Uncle Sam stood behind Fannie and Freddie.

NOTES

1. There’s a problem with taking out a loan for 103 percent of the price of the house when the price of the house exceeds the value that would be there without the opportunity to get into this lottery. That problem is the appraisal. There are numerous media accounts of how the appraisal process was corrupted—lenders stopped using honest appraisers and stuck with those who could “hit the target,” the selling price. Why would a lender want to inflate the appraised value? Normally they wouldn’t. But if you’re selling to Fannie or Freddie, you don’t have an incentive to be cautious. Andrew Cuomo, the former US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) secretary who increased Fannie and Freddie’s affordable housing goals, and currently the attorney general of New York, investigated Washington Mutual and Fannie and Freddie’s roles in corrupting the appraisal process. Fannie and Freddie ended up making a $24 million commitment over five years to create an independent appraisal institute. Cuomo has not revealed what he found at Fannie and Freddie that got them to make that commitment. See Kenneth R. Harney, “Fighting Back Against Corrupt Appraisals,” Washington Post, March 15, 2008, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/03/14/AR2008031402007.

2. See Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997, Library of Congress, THOMAS, http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d105:HR02014.

3. Federal Reserve Bank of New York, “Federal Funds Data,” http://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/omo/dmm/fedfundsdata.cfm.

4. John Taylor blames poor monetary policy for much of the crisis. See Taylor, Getting Off Track. Greenspan’s “theya culpa” (in which he blames everyone but himself) can be found in Alan Greenspan, “The Crisis,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, March 9, 2010, http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Files/Programs/ES/BPEA/2010_spring_bpea_papers/spring2010_greenspan.pdf.

5. See Noelle Knox, “43% of First-Time Home Buyers Put No Money Down,” USA Today, January 17, 2006; and Daniel H. Mudd, “Remarks at the NAR Regional Summit on Housing Opportunities,” Vienna, VA, April 24, 2006.

6. Mudd, “Remarks.”

7. This was the growth in the middle tier (the middle one-third by price) in Washington, DC, in the Case-Shiller index for DC: http://www.standardandpoors.com/indices/sp-case-shiller-home-price-indices/en/us/?indexId=spusa-cashpidff--p-us----.