This chapter considers the cultural, historical, and methodological contexts that are at the heart of this book’s enquiry. It provides an essential frame of reference for the chapters that follow and offers a timely intervention into current methodological debates in periodical studies. In two sections, the chapter examines, first, the correspondence between tourism and nation-building in conceptual and material terms and, second, the magazine as a paradigmatic expression in print culture of that concurrence. Drawing on recent scholarship in tourism and Latin American studies, the first section situates the book’s focus on Mexico within the country’s remarkable emergence from the Revolution during the 1920s, contextualizing that significant juncture within the history of organized tourism there since the late nineteenth century to the present day. It then locates this book’s endeavours within the growing scholarship on tourism and nation-building in Mexican cultural history and recent considerations of the relation in Spanish America between tourism and visual culture. The second section, drawing on examples from the book’s corpus of magazines, elucidates the unparalleled properties of the periodical as an object of study within those contexts. It offers comprehensive observations on the magazine as a unique form, considering its defining admixture of visual and written material and its dialectical functions as archive and store. The question of different categories of magazine (e.g. the popular vs the more high brow) and their associated symbolic capital is also addressed here with specific regard to the magazines selected for study in this book, among the aims of which are to advance our appreciation of such texts beyond their value as source materials and to enrich our understanding of the diversity and complexity of the periodical field. The rich heterogeneity of this serialized form of print culture has broader methodological implications, which are pursued in the chapter’s final section.

Tourism and Nation-Building

Tourism has often been mobilized by developing countries as a form of nation-building, especially in the wake of economic and/or political crisis. 1 Indeed, as Florence Babb has shown in her ethnographic work on the subject in Latin America, ‘tourism often takes up where social transformation leaves off and even benefits from the formerly off-limits status of nations that have undergone periods of conflict or rebellion’ (2011: 2). At face value, however, that coincidence of tourism and revolution (as it has manifested in Latin America) might seem anomalous, the two scarcely compatible phenomena: the first, the commercial organization of ‘leisure’ travel and sightseeing, which are often regarded as superficial and exploitative practices; the second, the forcible overthrow of a government in the name of social justice. 2 Further scrutiny of the experiences and ‘logic’ of the two, however, reveals a closer affinity that is camouflaged by those definitions. Dean MacCannell hints at this association, notwithstanding the early admission in his groundbreaking book The Tourist that, ‘Originally I had planned to study tourism and revolution, which seemed to me to name the two poles of modern consciousness – a willingness to accept, even venerate things as they are, on the one hand, a desire to transform things on the other’ (1976: 3). 3 In fact, MacCannell’s study insinuates an epistemological affiliation between tourism and revolution that belies that assertion. That is, while at first he articulates his understanding of the two in binary terms, MacCannell goes on to characterize them as exemplary, synchronous components of modernity: if ‘“The revolution” in the conventional, Marxist sense of the term’, he writes, ‘is an emblem of the evolution of modernity’, ‘“the tourist” is one of the best models available for modern-man-in-general’ (1976: 13, 1). Indeed, the very idea that tourists ‘accept/venerate things as they are’ is revealed on closer inspection to be a limited understanding of their activities. For, as MacCannell himself and other scholars of tourism have demonstrated, it is curiosity and desire for engagement with rather than pure detachment from culture and society that fuel the tourist’s motivation to travel. Moreover, if we think of transformation as the core, driving impulse of both revolution and tourism, a closer correlation of the two phenomena starts to look more conceptually viable. The former is about a metamorphosis of political structures and institutions, while in the latter, the change of the traveller’s environment, from home to away, may entail a form of ‘internal travel … an exploration, or discovery, of feelings’ or identity (Clark and Payne 2011: 117). Each involves a transgression of boundaries, whether it be of socio-political classes, spaces, geographical frontiers, or emotions. In short, to invoke and adapt Eric Leed’s seminal observations on travel, in empirical and figurative terms, both tourism and revolution ‘[are] a source of the “new” in history … creat[ing] new social groups and bonds’ (1992: 15).

The correlation between tourism and revolution is more than conceptual, however: it has strong historical foundations in various Spanish American nations that have undergone armed conflict identified as revolutionary. Countries such as Cuba , Nicaragua, and Mexico have at different junctures of the twentieth century become magnets for what Maureen Moynagh calls political tourism, precisely because of their histories of armed rebellion. 4 Most often the purview of mobile ‘vulgar cosmopolitans’ who ‘pursue affiliation and belonging with struggles ostensibly not their own’, for Moynagh, political tourism has an affective dimension, as it expresses a form of ‘long-distance empathy’ with anti-imperial and anti-fascist struggles across the world, and seeks to de-construct international borders ‘in acts of affiliation and commitment’ (2008: 6). 5 If the 1959 Revolution, and the imposition of the 1962 US embargo on travel and trade, discouraged the kind of mass tourism to Cuba seen in the 1950s, the island nonetheless became a hub for intellectuals, writers, artists, and activists who flocked there to see revolutionary society and contribute to processes of social transformation then taking place (Jayawardena 2003). ‘Tourist-revolutionaries’ from North America took circuitous routes to help cut sugar cane while others of an intellectual or artistic stripe (such as Susan Sontag, Mario Vargas Llosa, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Simone de Beauvoir) went ‘to make of their observation an active participation’ (Fay 2011: 408). Nicaragua, following the 1979 Sandinista victory, hosted an analogous horde of what poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti—himself a visitor to the country—wryly termed ‘tourists of revolution’. Those so-called sandalistas included figures such as Margaret Randall, Susan Meiselas, and Salman Rushdie on similar kinds of pilgrimage to those made earlier to Cuba, though the Nicaraguan state was keen ‘to shed the notion of [the country] as a place of political conflict and of danger, and [for tourists] to discover a land of beautiful landscapes and friendly people’ (Babb 2004: 549). In each of these cases tourism, animated by the triumphant formation of revolutionary states, is articulated and identified largely as an exogenous, elitist, and ephemeral affair, depictions that resound with that time-honoured, yet troubling dichotomy between traveller and tourist. Criticism of tourism as shallow and superficial, which underpins that persistent but ultimately reductive dichotomy, is frequently ‘more anecdotal than analytical’, however (Merrill 2009: 14). Indeed, resting on a rhetoric of moral superiority, it is open to charges of superficiality of its own. 6 On this theme, MacCannell wryly observes that, ‘God is dead, but man’s need to appear holier than his fellows lives’ (1976: 10). As he, Merrill, and others have argued, ‘discounting the intellectual and cultural depth of the tourist experience’ is specious as it disregards tourists’ historical agency as well as their significance in international relations (Merrill 2009: 13).

These factors are crucial to the context under scrutiny in this book, although at stake here is an iteration of tourism that differs in significant ways from the kind of ‘solidarity travel’ just discussed—in this instance, a modern Mexico attracting visitors from far and wide for its intriguing amalgam of social reform (in land ownership, education, and popular art), pre-Columbian archaeological sites and indigenous peoples. 7 In what follows, my interest in and engagement with tourism as a category stems not only from a shared scepticism of and enthusiasm for neutralizing that pervasive travel-tourism dichotomy. Fundamentally, it arises from the unique historical context, the endogenous development of tourism as a mass industry in Mexico—rather than a niche, vertically imposed ‘imperialist’ affair—and to the Mexican state’s attempts to foster tourism as a tool in its reconstruction after the Revolution (unlike Cuba) as ‘an industry made by and for Mexicans’ (Berger 2006: 2). 8 Indeed, some important work in Latin American and postcolonial studies in the last decade or so on tourism, to which this book aims to contribute, has undertaken a more considered reappraisal of its historical operations in the region. As Michael Clancy argues, such scrutiny is, if nothing else, an economic imperative: ‘Tourism deserves greater empirical attention due to its sheer size in the world economy and within the developing world’, he avers, since ‘roughly one in every four international tourist dollars is spent [there]’ (2001: 2). In consequence, much of the scholarly work on tourism in Latin America to date has tended to focus on those countries already mentioned as well as different Caribbean nations that have turned to ‘tourism [as] an agent for the refashioning of cultural heritage and nationhood’ after periods of particular upheaval and instability (Rosa 2001: 458). 9 Scholars in anthropology, geography, history, sociology, and cultural studies have in different ways illuminated how tourism can function ‘as more than just a form of imperialism, exploitation, or profit’. In doing so, they have contributed to a shift in thinking about this industry and activity away from ‘a simple system of cultural imposition’ to ‘an ongoing international negotiation’ in which cultural linkages between the global North and South are created and produce ‘ambiguous, interdependent relationships’ (Merrill 2009: 1, 9). Tourism, for Dina Berger and Andrew Grant Wood, for example, and as evinced in my case studies, can operate ‘as a form of potentially positive encounter … as a form of public diplomacy [even] because it is a kind of exchange among non-state actors that … can shape and even reorient perceptions of other people, cultures, and nations’ (2010: 108–110). As such, in concert with Berger, Grant Wood and others, this book regards tourism as a set of complex (trans)cultural practices and encounters, for which the long-standing caricature of the tourist/tourism visualised in Duane Hanson’s well-known lifelike sculpture ‘Tourists’, though amusing, is ultimately unhelpful. 10 Rather more useful in this context is historian Rudy Koshar’s affirmation—a reminder of the association of travel in all its modalities to ‘travail’—that ‘tourism finds its meaning through effort, contact, and interaction, no matter how programmed or structured’ (quoted in Merrill 2009: 14).

This is not to say that we should disregard the imperialist precedents and continuities of tourism: to be sure, in some circumstances tourism does resemble conquest and in Spanish America, the industry’s contradictions are more than evident. The cases of Cuba and Mexico attest to this. While the industry can restore the coffers of an ailing economy (whether, as in the case of Cuba, due to the US embargo since the start of the so-called Special Period, or, in the case of Mexico in the 1920s and 1930s, as a result of the protracted armed phase of the Revolution), tourism has had adverse effects that can undermine the original nation-building aspirations at stake. In Cuba and Mexico, for example, state encouragement of foreign capitalist investment has had equally compromising implications in terms of the two nations’ revolutionary credentials. In the former, the increasingly visible economic and social inequalities that emerged alongside the development of tourism in the island since the early 1990s have undermined the preservation of socialism and its egalitarian principles, a central paradox given that it is precisely ‘Havana’s oppositional role as anticapitalist capital [that has had] … a potent and enduring heterotopic function’ in sustaining the international image of Cuba as a ‘political fantasy, nostalgic commodity, and Cold War fetish’ (Dopico 2002: 458). In Mexico, the pace of industrialization and the development of tourist infrastructure in the 1940s onwards (to which I return in Chapter 3), part of a ‘public relations effort to convince their northern neighbor that Mexico was a safe place to invest’ (Nilbo and Nilbo 2008: 42), effectively contradicted the revolutionary state’s former economic nationalism as well as paradigmatic Cardenista land reforms. Moreover, in tandem with those inequalities arose new kinds of corruption, whether in the form of a revivified economy of sex tourism in Cuba or in diverse manifestations of political misconduct in Mexico at the start and throughout its subsequent development of tourism, as when the channelling of state resources into industrialization programmes has ‘coincided with the private interests of key functionaries’ such as President Miguel Alemán himself (Nilbo and Nilbo 2008: 38). Nevertheless, it is precisely the complexity of these experiences, as Babb suggests, that befits consideration of ‘the ways that tourism and revolution intersect [in the region]…particularly at a time when postsocialism is heralded and globalised capitalism reigns’ (2004: 553). This book aims to enhance and advance such considerations with specific regard to Mexico, where from the 1920s onwards tourism allowed the country to participate in modern capitalism and overcome the serious financial problems bequeathed by Revolution, as well as a foreign debt exacerbated by the Great Depression. For tourism in the post-revolutionary period, as Alex Saragoza writes, ‘contributed substantively to the nationalization of cultural expression in Mexico and its projection outside of the country … [and ultimately] presented the dramatic making of the nation’ (2001: 91, 93, my emphasis). A brief contextualization of the development of tourism in the country will be useful at this juncture.

Organized tourism to Mexico from the north began in the 1880s, stimulated by an acceleration in the construction of railroads, which multiplied in number at that time. 11 Indeed, Mexican rail-road companies also became ‘prolific publishers of tourist materials and travel guides’ (Boardman 2001: 32), providing information on where to stay and what to do along their routes. At the turn of the twentieth century, President Porfirio Díaz invited foreigners to settle in the north of the country in an attempt to populate the region so that American immigration there almost doubled between 1900 and 1910. The following decade saw increasing numbers of Americans travelling to Mexico, a flow that would only increase with the boom in air travel in the late 1920s (famously publicized by the ‘hero-tourist’ Charles Lindbergh’s 1927 goodwill tour to Mexico to promote commercial air transport), while the border states received a substantial boost in visitor numbers following the Volstead Act’s prohibition of alcohol (Boardman 2001: 63). In addition to the ‘northern bohemians … drawn for the most part from the US middle and upper classes [who] discovered a postrevolutionary oasis for artistic experimentation, social reform, and rural tranquility’, the 1920s and 1930s saw large numbers of cultural and scholarly exchanges develop between Mexico and the United States as well as an influx of travellers and exiles from Europe who sought participation in the country’s ‘exhilarating laboratory for revolution and modern socialism’ (Merrill 2009: 3, 31). In turn, the Mexican government focused its efforts on developing tourist infrastructure in the 1930s and 1940s by constructing new and improved highways and by establishing tourism offices in all major US cities. As a result, between 1939 and 1950, tourism receipts in Mexico grew from $21.7 million to $156.1 million, the greatest percentage of which came from US visitors (Boardman 2001: 69).

Border tourism, as it was defined at the time, constituted almost 60% of the total [tourism in Mexico]. Short stays contributed to relatively low spending per visit and the reputation of border areas as centres of vice and smuggling intensified. (2001: 45)

Indeed, as a consequence of social problems associated with border tourism, subsequent Presidents Adolfo López Mateos and Gustavo Díaz Ordaz ‘wavered in their enthusiasm for [the industry] and were hesitant to promote it more strongly’ than had, say, Alemán and Ruiz Cortínez (2001: 47).

By 1970, Mexico was drawing 2.2. million tourists, a figure that nearly tripled by 1991, thanks to growth rates over that period exceeding 5% for arrivals and over 10% for receipts. It was then in the early 1970s that newer beach resorts, such as Cancún, Ixtapa, and Los Cabos, started to become established with increasing state endorsement and investment: eventually, they would draw tourism away from the traditional centres of Mexico City, Guadalajara, and Monterrey (Clancy 2001: 62). In 1974 a significant institutional change—the elevation of the Department of Tourism to Secretaría status (a cabinet-level ministry), which gave it greater prestige and (albeit still limited) financial resources—enabled the state to intervene further in the tourism sector (Clancy 2001: 56). Mexico has since become one of the largest tourism export sectors in the Third World: ‘By 1996 the country drew more than 40% of all international tourists to the Western Hemisphere outside the United States and Canada and ranked seventh in the world in popularity’ (Clancy 2001: 10). Today, tourism accounts for 10% of total national employment (Berger 2006: 3). Although in recent years the spread of drug cartels and attendant violence has had adverse effects on different regions of Mexico (most notably Acapulco, the northern states but including Mexico City), tourism in the country remains a more than $12 billion-a-year-industry. 14

Throughout its development and promotion of tourism, Mexico has had to contend with long-standing negative images of it in the US press, which stem back to the nineteenth century and beyond. These include the view that Mexico and Mexicans are ‘retrograde, both culturally and racially, by virtue of their “mongrelized” mestizo image’, a condition (consolidated particularly during the Revolution) apparently marked by violence and childishness, a propensity towards hedonism and barbarism, as well as an inclination for dishonesty and theft (Anderson 1998: 27). If the country’s ethnic diversity provided an account of its ‘backwardness’, it was also—counter-intuitively—a source of difference to be exploited in subsequent attempts to promote tourism. Advertising campaigns aimed at international travellers in the 1920s and 1930s thus tended to focus on the country’s natural resources as the main attractions, later adding themes of the indigenous peoples, regional costumes, and folk arts, as well as Mexico’s proximity to the United States by rail. In the 1940s, however, as indicated above, Alemán made concerted efforts to modernize Mexican tourism, to move it away from its dependency on the folkloric and to cultivate a more cosmopolitan vision of the country: ‘the touristic promotion of Mexico by the 1940s signified the transition from essentialist cultural depiction to one less reliant on the appeal of authenticity, monumentalism, and folklore’ (Saragoza 2001: 108). During that decade of accelerated modernization (when WWII in fact aided tourism to Mexico as it had closed off alternative destinations, especially for North Americans), in touristic representations, Mexico was sold ‘as the embodiment of both modernity and antiquity’ (Berger 2006: 56). 15 The result was that Mexico’s reputation in the north shifted in and after WWII from that of the barbaric to the good neighbour. 16 As Berger has illustrated, the combination of the modern and ancient proved to be persuasive as well as pervasive in the visual and narrative rhetoric of tourism. While images of the mestiza and regional types continued to be deployed to personify the Mexican nation and its tradition of hospitality, other images used to advertise Mexico City in the 1940s onwards ‘consistently compared the capital to other well known US and European cities such as New York, London or Paris’ and included ‘fashionable, cosmopolitan women to personify modernity in an effort to make the capital desirable and familiar to tourists’ (Berger 2006: 101, 105).

If developing nations such as Mexico have deployed tourism as a panacea to economic woes, central to this endeavour have been attempts like these to counteract deleterious images in ‘the international imaginative atlas’ (Fay 2011: 408) in visual and narrative form. In consequence, a striking feature of recent scholarship on tourism in Latin America has been the central role played by various forms of cultural production in the methods being brought to bear on its study. Geographers, historians, and anthropologists alike have looked to myriad representational practices—including tourist posters, postcards, photographs, and travel accounts—as source material for their understanding of this industry. In her work on tourism and photography in the Anglophone Caribbean, for example, Krista Thomson observes that in order to address the time-honoured stigma associated with the West Indies as breeding grounds for potentially fatal tropical diseases (such as yellow fever, malaria, and cholera), touristic-oriented representations of the Bahamas and Jamaica depended on a domesticated version of the tropical environment and society. Nature and the ‘natives’ were tamed and disciplined in photographs and postcards of these sites, which were marketed as ‘premodern tropical locales’, conveying not only the success and entirely benign legacy of colonial rule but also encoding the kind of safety travellers could expect when they arrived in those destinations (Thomson 2006: 12). 17 In doing so, such visual images presented a ‘particular Edenic (a holier than thou) image’ of these nations, recreating their colonial past as ‘clean, wholesome, and a world without conflict’ (2006: 272). Likewise, Ana Maria Dopico notes that ‘the image machine reproducing Cuba for a [contemporary] global market’, while exploiting Cuba’s exceptionalism, ‘in fact relies on tourism’s capacity to camouflage revolutionary Havana into consumable mirages, visual clichés that disguise or iconize the city’s economic and political crises’ (2002: 464). 18

While existing studies on tourism in the region draw on visual forms such as photography and postcards (Thomson, Dopico) and an array of other sources including travel writing (Merrill, Schreiber), tourist brochures, and radio broadcasts (Berger, Saragoza), among other textual and visual representations, this book focuses exclusively on the magazine. It perceives and champions the magazine as an essential but hitherto overlooked part of Mexico’s ‘culture of the visual’, whose own illustrations in the form of advertisements and maps, which are the subjects of the following chapters, to some degree evince tropes and tendencies of the kind identified by scholars such as Thomson and Dopico. While I am interested in the magazines’ features, articles, and editorials, the following chapters devote considerable attention to those promotional and cartographic features of their visual paratextual apparatus, not only because of their emblematic relation to the ‘industry without chimneys’, but also because this kind of rich but nominally ‘marginal’ visual content merits scrutiny in its own right as well as in relation to the magazines’ remaining content. As Hammill et al. observe, though ‘periodical studies is frequently structured by an implicit hierarchy of content that privileges the story over the advertisement, the enduring over the fashionable, or, more broadly, the exceptional over the repetitive’, magazines need to be understood as and for their character as miscellany, as ‘interlocking systems of mediation’ (Hammill et al. 2015: 6). Moreover, while advertisements and maps share the same cultural economy and contexts as other visual forms, they have yet to be fully appreciated in relation to Mexico’s broader visual culture, a lack of connection that, as Magalí Carrera notices apropos of maps, is both ‘curious and problematic’ (2011: 4). 19 Such an oversight, to which I return in more specific detail in this chapter and Chapter 3, can be partly explained by a prevailing tendency to discount or simplify matters concerned with marketing or else to affiliate maps with a purely scientific domain, in both cases ignoring the relevance or relation of these visual forms to the aesthetic or the symbolic realms. Yet, as this book argues, such images are intimately connected to Mexico’s contemporary visual and political culture. Further, when read within their historical contexts of production and in relation to the other heterogeneous material between the magazines’ covers, they convey complex, sometimes even discrepant meanings. Indeed, as much as photographs and postcards, this kind of illustrated periodical material attests acutely to the ways in which tourism functions both as a commodification of Mexican culture and a complex means of cultural affirmation. Thus, by concentrating solely on the periodical form, this book does not dismiss or simplify ‘the elements of bricolage’ (Moynagh 2008: 17) that an ostensibly more variegated corpus, such as that of other studies of tourism, by Berger or Moynagh say, might appear to offer. Rather, as I elucidate in the following section, the value of the magazine as a ‘single’ object of study lies in part precisely in its own compositional heterogeneity (that is, that it is a visual and narrative form) and its intermedial porosity, both of which belie any reductive idea of ‘uniformity’ or what Mikhail Bakhtin calls ‘monolingualism’. In what follows, I also argue that the magazine has an agile yet ‘archival’ quality that is remarkable when compared with other forms of cultural production, especially in the area of tourism , an industry with which it has a suggestive and historical affinity.

The Magazine: Store, Archive, Source

As a form, the magazine is a regular miscellany of articles and illustrations often focused on a particular subject or aimed at a particular audience/readership. It is distinguished by its contemporaneity or ‘newness’, that it is ‘continually on the move, across time’: responsive to events and developments in the area of its subject matter, it selects those that are deemed worthy of report or inclusion in its pages (Turner 2002: 183). As Eric Bulson points out, the little magazine (one of the periodical’s salient forms) came of age not long before WWI and was followed swiftly by the rise of Fascism and Nazism in Europe and the decolonization of countries across Africa and the West Indies after WWII: as such, Bulson avows, ‘[the periodical] is not something that simply registers the shocks during these tumultuous moments; it actively responds to them by establishing literary and critical communication when it could prove difficult, if not impossible’ (2017: 5). Such nimble and contingent qualities and, notwithstanding recurring predictions of its imminent demise, its continued proliferation as a form have afforded the magazine (and its ‘little’ iteration in particular) an innovative or experimental character that has long been put to radical ends. As Gorham Munson puts it in a charming 1937 article, the magazine has operated like a ‘potting shed where very rare and usually frail plants are given a chance of blooming’ (1937: 10). The currency from which such experimentation has sprung is amplified by the magazine’s weekly, monthly, or quarterly appearance; the serialization or ‘multiple periodical rhythms’ that are also one of the periodical’s defining features (Turner 2002: 188). The frequency of a magazine’s publication is determined by symbolic and economic rationales that have various material and epistemological implications, for, as Turner points out, ‘there is no single rhythm … no single cycle, no single motion which somehow contains it all’ (2002: 187–188). For instance, we might compare subjects that appear to ‘merit’ a periodical title of increased (daily, weekly) frequency, for example—current events, politics, satire—to others that have a more staggered (monthly) output, such as leisure pursuits and less topical issues. In essence, however, frequency is informed by affordability at the level of production and readership. In terms of the latter, as Richard Ohmann (1996) has shown in his pioneering work on North American ‘commercial’ periodicals, in the late nineteenth/early twentieth century ‘mass market’ magazines had to extract themselves out of the realm of luxury consumption in order to attract large audiences with money to spend: they did so by lowering their price and by selling more advertising space to cover the costs of production. 20 More fundamentally, the question of how regularly an editor can afford to publish is the defining factor: historically, many of the so-called little magazines (and others), due to financial constraints and difficulties, have either amended the frequency of their output, interrupted and/or ceased publication altogether. Such is the case of Mexican Folkways and Mexico This Month , both of which received government grants and subsidies for their publication, the precariousness of which repeatedly affected their publication schedules and, following withdrawal, ultimately sealed their demise. Such state-funding arrangements are unique to Mexico when compared with many titles in the Anglophone market that are considered in the existing scholarship on this form, though the ensuing relationship between cultural producers and the state was not necessarily straightforward: as Joseph et al. write, it was ‘typically asymmetrical … [but] invariably multifaceted, and power was rarely fixed on one side or another’ (2001: 7).

If the magazine is distinguished by its response to the new and by its recurrence, it also rests on a degree of belatedness. The magazine is not as urgent a publication as a daily bulletin, it does not ‘meet specific, local needs in the way a newspaper does’ (Ohmann 1996: 355). This, counter-intuitively, lends it a degree of ‘untimeliness’, although Turner suggests that the break inherent in serialization is precisely ‘the space that allows us to communicate’, the lapses in time in fact ‘where meaning resides’ (2002: 193–194). Notwithstanding, the magazine’s periodic appearance means that it runs the risk of anachronism from the very moment of publication, let alone of distribution, which (when on an interrupted or unreliable schedule such as those of this book’s case studies) adds an additional layer of adjournment and risk. 21 Its very in-frequency means that the magazine’s hold on its readership might be more tenuous than that of a newspaper or a novel, although serialization (of fiction, in particular) was one mechanism for retaining (and manipulating) readers’ attention and loyalty. Mexican Folkways , for the first two years of publication, 1925–1927, was published bimonthly and from 1928 to 1933 every three months, with an interruption in 1932. During its last four years of publication until 1937, only three issues of Mexican Folkways appeared, as monographic numbers on Mexican ‘masters’ José Guadalupe Posada and its ‘own’ Rivera. Its editor Frances Toor was apologetic about the discontinuous appearance of Folkways, due to intermittent government funding. In a 1927 issue she pledged to ‘do better in the future’ and promised ‘an accounting’ if there was any further suspension in publication; while in 1933, she lamented once again ‘find[ing] myself without [the] assurance of being able to continue publication. But Mexico is a land of miracles (and perhaps there will be another for Mexican Folkways eventually)’ (8:1, 1933, 2). On the other hand, letters from regular readers of Mexico This Month to lament or even sympathize with the magazine’s habitual tardiness were frequently published between its covers. For example, Elaine Snobar of New York wrote on 8 April 1970 of the months of delay she waited for the magazine: ‘How could we possibly take advantage of anything which happened more than a month ago?’ (Brenner 1968). Meanwhile , George Blisard of Waco, Texas, was more generous about the magazine’s late arrival, suggesting that ‘these people who write letters complaining of not receiving issues on time … have either never been to Mexico or else spent only a little time there [for] the things that make the publishing date uncertain are the basic reasons that Mexico is such a wonderful place’ (Brenner 1968). Brenner thematized this belatedness in Mexico This Month, acknowledging and answering her readers’ complaints in the magazine’s pages. On one occasion she admitted to its late publication due to their printer’s attempt to bribe them for more money: ‘If you have jumped to conclusions and figured it’s Mexican printers who act in this way, the answer is, they don’t’, she wrote, ‘This one was a foreigner … carried away by the fact that he’s the only plant in town that does photogravure’ (4: 11, 1958: 6). Brenner’s broadside against time-honoured preconceptions of Mexican degeneracy here was typical of her efforts throughout the magazine to contest the country’s unfavourable image in the north, a subject to which I return in Chapter 3.

In other ways, a magazine’s ‘infrequency’ can have generative properties. Its reiterated and recurrent articulation of a particular position, rhetoric or subject matter has a legitimizing, institutionalizing function in terms of ideology and subject matter. Indeed, the lack of immediacy together with such recurrence furnishes the magazine with archival or memorializing potential, conferring a greater sense of permanence and ‘authority’ on it perhaps than, say, that of a newspaper. As such, even when not advertising the manifestos of a particular avant-garde movement, say (as in modernist periodicals), the magazine of any kind is a purveyor of ideology and operates as a form of manifesto itself. 22 Mexican Folkways is a good example of this. Insofar as ‘it contributed directly to the effort to collect and disseminate knowledge about the country’s vernacular traditions and cast them as part of a coherent whole’ (López 2010: 103), it essentially operated as an expression or programme of state policy to integrate Mexico’s indigenous peoples. Indeed, it is as a repository of this sort that this magazine has subsequently become most prized by scholars, although, as I argue in chapter 3, this in turn has lead to some significant oversights. By contrast, the enterprising Brenner actively mobilized the magazine’s ‘archivable’ potential in discrete ways. From its inception Mexico/This Month was circulated to schools and college libraries in the United States (the costs of their subscriptions covered by the US government) and, during the 1960s, Brenner planned an educational toolkit, among other items, as a spin-off to the magazine. The kit was to include folk art and a film package as well as supplementary teaching material for the orientation of children of Mexican origin in the US public school system. In this way, Brenner foresaw the magazine’s long-term ‘social’ function. As such, both she and Toor can be seen as incipient ‘archive entrepreneurs ’ in Antoinette Burton’s terms, whose periodicals contradict the tendency of ‘much of the material that documents tourism …[to be] by nature ephemeral’ (Boardman 2001: 17) and challenge elitist histories. 23 In broader terms, the magazine as archive in this vein complicates further the question of its ‘untimeliness’. For if the magazine is ostensibly concerned with the new and the now, but, on publication and reception is always already ‘belated’, its archival and archivable potential (foreseen by both Toor and Brenner) is also forward-looking. For, as Jacques Derrida has famously observed, ‘The archivization produces as much as it records the event’ (1995: 16–17). This is a particularly significant gesture in the context of a country in the tumultuous throes of nation formation.

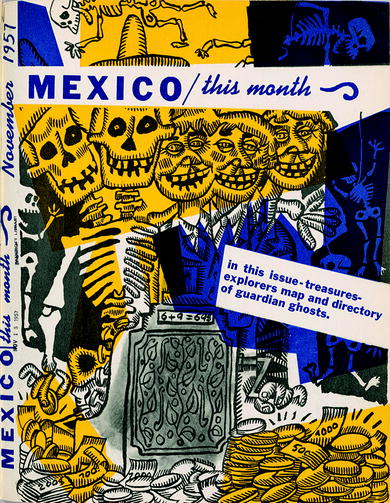

Front cover of Mexico This Month, 3:1, 1957

Mexico This Month was also well received in the north in reviews in titles such as Sunset and Esquire, where it was favourably compared with the New Yorker (Fig. 2.1). In a bulk ‘controlled circulation’ arrangement that was part of its state sponsorship from Nacional Financiera, Mexico This Month was also distributed to Mexican consulates and embassies across the world, which allowed it to reach readers at home, in the north, as well as in Europe and Asia. Composed by both Mexican and North American writers and artists, and providing reading material to audiences located often well beyond Mexico’s borders, both titles testify to the globality of the magazine as a form, offering ‘a place in which writers, readers, critics, and translators could imagine themselves belonging to a global community that consisted of, but was not cordoned off by, national boundaries’ (Bulson 2012: 268). This is not to overstate the extent or depth of these magazines’ networks and influence, nor to disregard their darker side: as Bulson puts it, the more a magazine travels, ‘the less [can] be known about where it was ending up, how it was being read, and by whom’ (2017: 16). 24 Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge the hemispheric, intercultural authorship and readership at stake in the titles considered in this book, within the context of a unique geopolitical relationship during the period in question, which has few parallels elsewhere. 25

Advertisements in Mexican Folkways, 4:1, 1928

The magazine, straddling cultural and commercial arenas, is a hybrid, collective and intermedial form, its production and design the result of the collaboration of writers, artists, photographers, and readers, not to mention advertisers, publishers, ‘sponsors’ and distributors. It is fundamentally dialogic on three levels, as Suzanne Churchill and Adam McKible (2007) have emphasized: it is dialogic within its own pages, in the interplay between different magazines, as well as in relation to the larger public sphere. Questions of authorship, taking named, pseudonymous and anonymous forms can, as with readership, be difficult to disentangle. (This is especially the case in a bilingual title such as Folkways, which printed mostly simultaneous, sometimes anonymous translations of its articles in English and Spanish.) Nevertheless, for all its discontinuity (of form and publication schedule), the magazine can gain coherence from a coterie of established contributors with a shared ‘world view’, or from continuous editorship. 28 In the case of Mexican Folkways , the two anchors were founding editor Toor and the magazine’s art editor, a post that was briefly held by Jean Charlot and then Diego Rivera; there was also a core of contributing editors including Salvador Novo, Carleton Beals, and Tina Modotti . Likewise, Mexico This Month was only ever edited by Anita Brenner , who had contributed to the inaugural issue of Toor’s periodical. Both women were inveterate travellers and travel writers, authors of well regarded and much-reprinted travel guides to Mexico. In this respect, Toor and Brenner can be thought of as archons in Derrida’s formulation of that figure; that is, guardians ‘accorded the hermeneutic right and competence … the power to interpret the archives ’ (Derrida 1995: 2). 29 Driven by a personal and public archive fever, editors such as Toor and Brenner endeavoured to ensure the ‘security’ and continuity of their magazines’ content and publication (insofar as they could in the funding and media landscapes of their eras). In a 1926 issue of Folkways, Toor lamented that ‘if I personally didn’t carry out all the labours from distributor to editor, only for the pleasure of seeing that the magazine continues publication, it wouldn’t exist’ (1:4, 1926, 29). Meanwhile, Brenner was known for her ‘indomitable will, definiteness of purpose and unwillingness to brook criticism or suggestion’ in the editorship of Mexico This Month (Brenner 1959). This testifies to the editor not only ‘act[ing] like [a] narrator’ over a magazine’s lifetime but, like its contributors, also taking on the role of character (Bulson 2012: 272). Such long-term editorships speak once again to that notion of jurisdiction mentioned earlier—the magazine as ‘institution’—as well as to the cross-fertilization of different transnational intellectual networks in print culture in Mexico during this period. They also speak to the prolonged, dynamic activity of women magazine editors in Mexico at that time, further consideration of which lies beyond the scope of the present study but of which there is a respectable tradition in Spanish America more widely.

In sum, the magazine is a discontinuous but coherent form: contemporary, ‘spontaneous’ but untimely, it has suggestive, dialectical affiliations to both store and archive. It is a malleable, mobile, and very much public work: a rich and complex assembly of material that raises the possibility, indeed, urgency of a number of potential methodological approaches to its study. In general terms, following Peter Brooker and Andrew Thacker, the magazine’s composite form requires us to consider what they call the internal and external periodical codes . That is, the magazine obliges us to take into account its textual and design features (page layout, length, number, use of illustrations, ads, and type of paper and so on). Equally important, however, is its materiality, the ‘media ecology’, distribution contexts, and financial support, the ‘business’ end of operations. To date, these features have tended to be studied unsystematically or in separatist fashion, by scholars working in distinct disciplinary silos whose findings have been published either in ad hoc publications or in editions of anthologized essays about a particular country/region’s print culture, rather than in sustained monographic studies or series. Examples include work in sociology on, say, the portrayal of masculinity or femininity in popular lifestyle magazines (Winship 1987) or Catherine Lutz’s and Jane Collins’s ethnographic study of National Geographic, based on semi-structured interviews, reader surveys, and analysis of the magazine’s photography (1993). There is also work by historians, such as Lydia Elizalde (2007) or Saul Sosnowski (1999), whose editions of collected essays on periodical culture in Latin America provide helpful introductory overviews. In the Americas, it is notable that the fine, now canonized monographic works on single and singular periodicals—by authors such as John King (on Sur and Plural), Richard Popp (on Holiday), and Guillermo Sheridan (on Los contemporáneos)—are relatively few in number and although they are invaluable cultural histories they conduct little analysis of their magazines’ textuality (their internal structure, external design, and shape).

Although, of course, ‘there is no one way “to do” periodical studies’ (DiCenzo 2015: 36), perhaps there is something about the relentless novelty and perceived ephemerality of magazines, to which I referred above, that has worked against either more coherent or consistent forms of engagement with them and/or the establishment of a well-defined set of methodological frameworks in the field. To be sure, the question of number and scale is significant here, as Bulson explains: ‘There are too many magazines to account for, somewhere in the tens of thousands, maybe even more. … the impossibility of collecting … empirical data has a lot to do with the size of the print runs and the fragility of the materials’ (2012: 269). Whether in terms of locating a full and complete print run of a magazine or mapping the periodical culture of a particular period or region, addressing what Scott Latham and Robert Scholes call the holes in the archive can be a difficult task. Scholarly ‘search and rescue’ work (Bulson 2012: 285) has been endeavouring to address these very issues, to arrest the magazine’s ad hoc diffusion and to salvage it from its hitherto vulnerable existence. The burgeoning number of digital archiving projects and periodical collections in the Anglophone world (from JSTOR, Project MUSE, to the Modernist Journals Project of Brown University, among others) attests to this. The publication of anthologies and volumes such as the Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Global Modernist Magazines and the establishment of journals such as the Journal of Modernist Periodical Studies, societies and associations for the study of periodicals in different regions, such as RSVP and RSAP in the United States and ESPRiT and NAPS in the UK, are further significant developments. 30 Yet, while on one level such activities attest to the growth of a veritable academic industry, there is much still to be accomplished especially in non-Anglophone regions of the world, where circumstances in what Patrick Leary has called the ‘offline penumbra’ (Hammill et al. 2015: 4) remain far from the rather utopian situation described by Bulson, who avers that ‘from now on it will be impossible not to know the little magazine through … digital technologies, interfaces, and archives ’ (2017: 32). 31 In chorus with Leary, Maria DiCenzo rightly points out that one of the risks with digitization ‘is that if it is not there many assume it does not exist’ and, in fact, it is not a question of ‘how much, but, rather, how little [periodical material] is available in digital form’ (2015: 31). In this respect, though not discounting the value of digitization, and mindful of the challenges presented by international archival work with analogue periodical forms, scholars of Modern Languages or in languages other than English, especially those of us working in interdisciplinary, transnational contexts (and less wedded to the traditions of single-author study), are well placed to make advances in periodical knowledge and scholarship. As DiCenzo argues, ongoing work with print and manuscript sources is critical and ‘will play a central role in keeping the offline penumbra on the radar’ (2015: 32). This is one of the central endeavours of this study.

In essence, one of the essential tasks for scholars of magazines in whichever format is to adopt a catholic approach to the very categories that have emerged to date to define and delimit them. This requires engaging with the high and the middlebrow, identifying and acknowledging the overlap between them as well as their differences. It is about moving away from the ‘valorizing of literary and artistic ventures over commercial enterprises’ that has characterized periodical studies to date, to counteract the prevailing tendency identified by Robert Scholes to ‘exclude middles and emphasize extremes’ (2007: 218). While categories can be useful frames of reference, it is also necessary to acknowledge the porosity and fragility of their boundaries in practice, especially in active ‘dis-identifications’ with criteria—or ‘brows’—that have been defined from the top down (DiCenzo 2015: 30). Indeed, as Churchill and McKible aver, ‘attention to the wide array of periodicals can [only] enhance our understanding of modernity’ (2007: 7). 32 I emphasize this point because it is without a doubt that it is the little magazine in English, the fruit of the institutions that sustained and promoted modernism, which has become paradigmatic in periodical studies. Though it is a term that ‘cannot be applied universally’ (Bulson 2012: 269), two features distinguish the so-called little magazines. First, that they have lived what Brooker and Thacker call ‘a kind of private life’ on the margins of conventional culture, from where they articulate adversarial positions on the ‘new’. A second characteristic is their putatively non-commercial nature, that they ran on a small budget and had short print runs. As such, the little magazines spoke to a very limited group of so-called ‘intelligent’ readers (usually no more than one thousand), the small circulation ‘seen as a marker of success in reaching [those] high in cultural capital’ (Brooker and Thacker 2010: 7). 33 Recent work on modernist magazines has shown, however, that they by no means eschewed commerce entirely, either through advertising or deploying aspects of visual culture associated with it, and that some little magazines did reach larger audiences (issues to which I return in the next chapter).

The magazines of this book’s corpus testify to the need to take an expansive, inclusive view of the form. In fact, the particularities of my case studies’ content, composition, and circulation distinguish them in the publishing contexts of their day and from the kind of titles that have principally concerned scholars in periodical studies to date, the ‘little’ modernist magazine of the kind analyzed and/or anthologized in the Anglophone tradition by Brooker and Thacker and in Latin America most notably by King. Mexican Folkways and Mexico This Month cannot be considered equivalents to modernist serials, though they have some significant things in common with them (the use of manifestos, and, in the case of Folkways, a strong affiliation to an artistic avant-garde tradition and an unknown but probably small circulation). A significant example of cross-fertilization between such categories is the statement of objectives by the more obviously ‘popular’ Mexico This Month in the form of a manifesto, the trademark of the avant-garde periodical, which is discussed further in Chapter 3. This book enquires into magazines that were invested in mass culture (a term with heightened ideological resonance after Mexico’s Revolution) which, rather than dwell on the margins, were much more obviously present in and spoke to public and national life. These titles also engaged with and in commercial activity, and, in the case of Mexico This Month at least, enjoyed healthy circulation numbers, though admittedly to a more modest degree than mainstream Anglophone titles such as the paradigmatic National Geographic. There was substantial hybridization in authorship in these magazines too. Though Brenner regarded Toor as a ‘bungl[ing]’ ‘fool’ who ‘feels too superior for suggestions’ (Glusker 2010: 129), like her, many other writers and artists such as Charlot and Rivera who contributed to Folkways and other avant-garde titles in Mexico also turned up in the pages of Mexico This Month . Evidently, the ‘line between the mass market and the modernist magazine [was] never an absolute one’ (Morrison 2001: 4), a factor that once again complicates questions of readership of these titles as well as symbolic capital across the market. These magazines’ resistance to compartmentalization destabilizes categories of high and middle/lowbrow, elite and popular, as well as culture and commerce, which are the fulcrum of much of the existing scholarly work on Anglophone and Latin American periodicals. Indeed, they speak clearly to the imperative outlined by Hammill and Smith in their work on Anglophone and Francophone Canadian periodicals, that ‘magazines cannot be categorized into a stable hierarchy of low, middle, and highbrow titles’. Ruling particular titles in or out of such bounded categories, say Hammill and Smith, is problematic not only because of the diversity of content which might appear in a magazine but also because of the way a magazine’s character tends to alter over time, whether in response to external factors or as a result of staff changes: ‘The appeal of most magazines is based on the varied selection of content they offer, and this means that they can transmit “mixed messages” in ideological terms as well as at a cultural level’ (Hammill and Smith 2015: 9–10). Indeed, the material and thematic changes to Mexico This Month over its lifetime, which I discuss further in Chapter 3, had implications for its readers and subscribers precisely in this respect. The cancellation of its subscription to Mexico This Month by the San Diego Museum of Man in August 1971 speaks to this issue. Following what it saw as the magazine’s ‘change in nature’, it wrote: ‘If you have plans to make [it] a trifle more “scholarly” we might consider a[nother] subscription. But six dollars is too much for our budget to include a current events magazine’ (Brenner 1971).

Another key task for periodicals researchers is to ensure that our methods correspond to the complexity of the material at hand. Notwithstanding the inextricable links between history, historiography, and periodical studies, this involves redeeming magazines from their prevailing role as source material, mined solely for discrete pieces of information or treated only for historiographical interest. To be sure, periodicals are invaluable tools for ‘telling different stories about the past in a specific period or national contexts or comparatively’ (DiCenzo 2015: 31), as they do in this book. Yet, the very composition, material culture and history of magazines to which I have referred behoves us to read them as autonomous objects of study which require an engagement with not only their visual and discursive material and the interplay between their constituent parts. We need also to take into account their narrative trajectories—the magazine’s own biographies—over their lifetime in print. It is not unusual for readers or scholars to be unable ‘to say much about [a] periodical as a whole’ (Latham and Scholes 2006: 517). Such is the case with Mexican Folkways , which, as I illustrate in this chapter, is now canonized in the historiography but which has been largely ‘strip-mined’ for information relating to Mexico’s cultural revolution alone, rather than studied as a composite aesthetic object in its own right. In this respect, in the following chapters, I take seriously the need to consider the structure, shape, and design of magazines and to pursue a longitudinal study of their entire print runs, in order to enable an appreciation of their ‘narratological valence’ (Bulson 2012: 272) and to counter a prevailing tendency to raid them for/of material (Latham and Scholes 2006). To take into account aesthetic, formal, and production matters within and outside their covers is part of this book’s inclusive endeavour to respect magazines not just as disaggregated sources of anecdote and information, but, to draw once again on Burton’s observations on archives, as ‘fully-fledged historical actors as well’ (Bulson 2012: 272; Burton 2005: 7).

Given the multiple transactions at stake in magazine culture (in terms of form, category, author/readership, financial arrangements, and national ‘affiliations’), research in this area requires a degree of agility, expansiveness, and patience. In this regard, Churchill and McKible propose a suggestive conversational model for the study of modernist magazines that can be usefully extrapolated to the analysis of other titles including those selected for study here. Their model spotlights the ‘temporal and temporary engagements, debates, and negotiations with [the field of periodicals] …and [acknowledges] the collective effort[s] involved in the production, organization, and dissemination’ of magazines, as well as ‘the social, political and economic influences that shaped [them]’ (2007: 14). The conversational model, for Churchill and McKible, needs above all to be inter- and multidisciplinary, that is, to apply the methods and approaches of, and involve researchers from, two or more disciplines. Such work is not only about plugging the holes in the archive of a form that historically has been (temporally) ephemeral and (financially and materially) fragile. Here patience is required, not least to access and piece together the biographies of periodicals that might not be digitized or complete in any archive, nor have any remaining business files. To be viable, claim Churchill and McKible, the discursive methodological model needs to be as diverse and co-operative as the field’s very object of study (therein the need for agility), so that, as Latham and Scholes argue, ‘periodical studies should be constructed as a collaborative scholarly enterprise that cannot be confined to one scholar or even a single discipline’ (2006: 528). In this book, I take my cue from Churchill and McKible’s conversational model in a number of respects, even if in this instance I do not adhere to the letter of its admirable multidisciplinary ambition. In essence, my enquiry, the work of a single scholar long engaged in interdisciplinary, intercultural research on the experience and practice of travel in all of its expressions, is still informed by the contextual, dialogic approach Churchill and McKible advocate to periodicals. In this instance, given their transnational and bilingual composition, circulation, and objectives, Mexican Folkways and Mexico This Month demand to be read in dialogue with coexistent periodical texts and within the context of historical developments of and between two nations (Mexico and the United States), two languages (Spanish and English), and, in light of the particularities of their author- and editorship, with each other. Such a (reformulated) conversational model is also opportune in terms of the consideration of two usually bifurcated historical periods in Mexico framed by the publication dates of Mexican Folkways and Mexico This Month, a matter to which I referred in the Introduction.

One of this book’s objectives, resting as it does on a consideration of each of the magazines’ entire print runs, is for the first time to tell the (hi)story, from genesis to extinction, of Mexican Folkways and Mexico This Month. This chimes with recent practice elsewhere in the field of periodical studies, as, for example, in work by Hammill and Smith on twentieth-century Canadian magazines. While mindful that no method can reproduce the experience of contemporary subscribers and readers, Hammill and Smith also underscore the necessity of reading ‘simultaneously’, that is, of ‘comparing different items that were published at the same moment – [and] reading across different magazines’ but also reading ‘longitudinally across several years of the same title, in order to discern patterns or shifts in design or content’ (Hammill and Smith 2015: 68, 108). In this book, such longitudinal reading is the foundation of this first scholarly study of Mexican Folkways and Mexico This Month as ‘entities’. Further, although I acknowledge the value and appeal of so-called distant reading in large collaborative post-digital periodical projects, the nature of my own (necessarily predigital) research is quite different. In this respect, I share DiCenzo’s broader concern with ‘the option of “not reading”’ provoked by the rise of computational research methods and its possible implications on reducing engagement with the very content of magazines (DiCenzo 2015: 30). There is, I contend, still much to be gained from close reading of the periodical and personal archival materials together (such as they exist), as textual analysis and discussion of the magazines’ visual and narrative matter in the following chapters testify. Indeed, Hammill and Smith advocate just such a methodology that combines close reading of individual magazine issues, as well as sampling, ‘accidental reading’, and broad survey. My study at different junctures conducts longitudinal reading, broad survey, sampling, and close reading of the two magazines in question but in doing so makes no claim to (what might in any case be an unattainable) comprehensiveness. This is not only due to my own limitations as a ‘sole practitioner’ in research that is inexorably emergent, but also to the limitations of the archive itself (whose gaps in respect of the business files of Mexican Folkways need to be acknowledged) and the age of the periodicals in question, which means, for instance, that an ethnographic survey of either title of the kind realized by Lutz and Collins with National Geographic is now impossible. Fundamentally, however, as DiCenzo observes, there are also choices at stake in all of this. In this respect, this book’s publication in an initiative such as Pivot is propitious as well as pertinent. Pertinent, because the radical objectives and timely publication schedule of this short-form publishing platform resound with the kind of innovation and frequency associated with the magazine as a form, as discussed earlier; yet propitious also because, once again like the very magazines I consider in the following chapters, the initiative aims to disseminate research that seeks to have a timely impact on critical and methodological debates in an emerging area of scholarship. Such is the task of the following chapters.

Notes

- 1.

As Peter M. Sánchez and Kathleen M. Adams point out, tourism allows developing nations ‘to exploit their scenic and heritage resources potentially instilling civic pride, while simultaneously generating new revenue, principally for the achievement of more important goals’ (2008: 41).

- 2.

For a general introduction to the idea of revolution see Goldstone (2014).

- 3.

In light of his work on revolution being unfinished, MacCannell opted to present his findings in/on tourism first, which he did to widespread acclaim, with a second edition of The Tourist published in 1999. I am indebted to Maureen Moynagh’s observations about this connection in MacCannell’s work. See Moynagh (2008).

- 4.

In turn, political tourism needs to be distinguished from a site-specific form of trauma tourism, as defined by Laurie Beth Clark: ‘the practice of visits to sites of past atrocity by those who have been directly affected and by others’. Paradigmatic sites of trauma tourism include Villa Grimaldi in Santiago, Chile, and Parque de la Memoria, Buenos Aires. See Clark and Payne (2011: 99).

- 5.

A paradigmatic example of this from outside the region is the Spanish Civil War, which attracted large numbers of ‘outsider’ participants and observers in the International Brigades.

- 6.

Moynagh concurs, writing of her reluctance to endorse the notion that ‘There is some fully authentic [the thus pure] way of moving through the world’ (2008: 14).

- 7.

A more recent—and for various reasons more complex—expression of this ‘solidarity’ paradigm in Mexico is the Zapatista National Liberation Army’s (EZLN’s) 2001 protest march from San Cristóbal to Mexico City, commonly referred to as the Zapatour.

- 8.

Berger sums up the differences: in Mexico, there would be government-financed highways, government-regulated PEMEX companies, locally owned restaurants and tourism would celebrate and champion things Mexican, like its celebrated murals, folk art, films, and music. In contrast, Havana’s tourism was not a benefit to the nation because foreigners, mostly US investors, owned many components of its tourism infrastructure including hotels, casinos, automobile dealerships, race tracks, resorts, and transportation companies. As a result, Berger notes, ‘US tourists did little for the island’s economy because their money fell into the pockets of foreigners, not Cubans … Cuban tourism [could thus be equated with] a loss of national sovereignty’ (2006: 19).

- 9.

Puerto Rico offers another instructive example. For more on this see Rosa (2001).

- 10.

‘Tourists’ is part of the collection (currently in storage) of the Gallery of Modern Art, Scotland.

- 11.

Though travel inwards to Mexico dates back to the country’s origins, numbers were few since Spain prohibited foreigners from entering the country during the colonial period. See Boardman (2001).

- 12.

Their relations were intermittently tested over issues such as the bracero programme (est. 1942), Mexico’s stance on Cuba and later over the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre.

- 13.

For more on such travellers, see Schreiber (2008).

- 14.

For more on this see ‘Mexico tourism feels chill of ongoing drug violence’, Wall Street Journal, https://search-proquest-com.libproxy.ucl.ac.uk/docview/870539015?rfr_id=info%3Axri%2Fsid%3Aprimo, accessed 8 June 2011.

- 15.

Indeed, after the war, the US military selected Acapulco and Havana as recuperation destinations for its servicemen, a choice that continued during the Korean War (Nilbo and Nilbo 2008: 36).

- 16.

Nevertheless, as Eric Zolov points out, there was a paradox at stake in this transformation in geopolitical relations during and after the ‘miracle’, which was disadvantageous to both countries. On the one hand, Mexico became ‘a vital outlet for U.S. capital and a reliable ally in the Cold War then underway’ and as such the left-wing nationalism which once characterized the country was contained. On the other hand, as the ruling class in Mexico became more conservative, the PRI also became more outwardly nationalistic, a strategy which ‘in turn generated various impediments to the full realization of U.S. goals – economic, diplomatic, and military – in the country and regionally’ (Zolov 2010: 250, 259).

- 17.

Picturesqueness, argues Thomson, was a key tool in this enterprise, erasing ‘unwanted, threatening, and undesirable elements, including people, out of the social frame’ (2006: 17).

- 18.

The virtual Havana that circulates in images of the island abroad, and which ‘keeps “out of sight” political conflicts that cannot be assimilated by the narratives of tourism and foreign investment’ (452), rests on two main subjects: the architectural ruins of Havana, and the apparently candid beauty of Cuban faces. Both of these are objects of an erotic gaze on everyday life in Cuba and are akin, in Dopico’s view, to the kind of ‘international travel pornography’ of National Geographic, which ‘reminds us that in spite of all the machinery of transfer, we feel no closer to a real subject or a real experience’ (2002: 477).

- 19.

John Mraz dedicates a chapter of his book on visual culture in Mexico to a small number of illustrated magazines. See Mraz (2009).

- 20.

The magazine’s rise as a form then correlates to the beginnings and growth of mass culture, Ohmann avows, a confluence that ensured not only widespread availability of readers but also spoke to more widespread affordability, if not affluence. He argues that ‘a national mass culture was first instanced in by magazines, reaching large audiences and turning a profit on revenues from advertising for brand named products … [a phenomenon that substantially] reestablished the American social order on a new basis’ (1996: vii).

- 21.

This is the case even when, in contemporary commercial or mainstream magazines, the appearance of individual issues actually anticipates the month of their publication—so that an April edition appears in March, for example—a trend that arose out of the stiff competition in the market for women’s monthly magazines. A counter movement to this well established anticipatory and highly competitive publication schedule (as well as digital developments) is the emergence of a slow journalism movement with quarterlies in the Anglophone world such as Delayed Gratification, which rest on long-form and more considered responses to current events than the 24-hour news cycle conventionally allows. See https://www.slow-journalism.com (accessed 8 March 2018). In Latin America, analogous ‘slow’ initiatives might include the work of CIPER Chile (https://ciperchile.cl) and Anfibia magazine (http://www.revistaanfibia.com) in Argentina. My thanks to Fiona Cowood and Alia Trabucco for bringing these to my attention.

- 22.

See Ytre-Arne (2011: 219).

- 23.

Burton employs the term ‘archive entrepreneurs ’ to refer to new millennium archivists such as the Lower East Side Squatters in New York. See Burton (2005: 2).

- 24.

Indeed, he points out that while the little magazine may have been made for the world, ‘it was never a medium that moved easily within it’, (2017: 16).

- 25.

The closest analogous context is perhaps that of Francophone and Anglophone Canada. For more on this see Hammill and Smith (2015).

- 26.

As Peter Brooker and Andrew Thacker point out, just reading the contents of The Dial between 1920 and 1929 is about equivalent to reading twenty-one books the length of James Joyce’s Ulyssees. Although, as they say, the level of difficulty involved is not comparable, the number of diverse contributors, ‘many now lost to literary history’, represent difficult challenges to the scholar versed in single-author studies (Brooker and Thacker 2010: 20).

- 27.

In this respect, National Geographic’s investment in photography is paradigmatic: its photo-essays functioning ‘in effect, [like] tourist trips with the editors, reporters and photographers acting as tour guides’ (Lutz and Collins 1993: 32). Hammill and Smith take issue with this analogy, however, suggesting it may be ‘misleading: tour groups have set itineraries and proceed altogether at the same pace, whereas periodical readers may each take a different route through a magazine’ (2015: 67).

- 28.

For more on this see Philpotts (2012).

- 29.

During her time in Mexico, Toor edited various travel guides to the country, including a motorists’ guide to Mexico, though the apogee of her ethnographic work is A Treasury of Mexican Folkways, an encyclopedia of traditional Mexican rituals, dances, fiestas, and ceremonies, which was first published in 1947. Toor became interested in Mexico’s indigenous peoples and cultures when writing her Master’s thesis at the University of California, Berkeley, where Alfred Kroeber, one of Franz Boas ’s former students from Columbia, taught. Once resident in Mexico, Toor worked as a researcher in ethnography and folklore at the Department of Anthropology. For her achievements as a scholar and in disseminating Mexican cultural productions abroad, Toor was awarded one of Mexico’s highest honours, the Order of the Aztec Eagle. Brenner was a prolific journalist and writer, who wrote for, inter alia, Atlantic Monthly, Fortune, Holiday , Mademoiselle, The Nation, New York Evening Post, and The New York Times Sunday Magazine. She penned two well regarded and now canonized books on Mexican art and history, Idols behind Altars (1929) and The Wind that Swept Mexico (1943), for which, as well as her promotion of the work of the major figures of the so-called Mexican Renaissance, she is most well known. Brenner was also recognized for her services to tourism in Mexico by former president Miguel Alemán with the award of an Aztec Eagle, though she refused it because it was an honour designated to foreigners. As Glusker notes, however, Brenner did accept a citation as a distinguished pioneer of tourism awarded by Alemán in 1967. Glusker (1998: 17).

- 30.

For more on the US context see Di Cenzo (2015) and Bulson (2017). For more on ESPRiT (European Society for Periodical Research) and NAPS (Network of American Periodical Studies), see http://www.espr-it.eu and https://periodicalstudies.wordpress.com respectively.

- 31.

Bulson warns that the increasing institutionalization of the ‘little’ magazine in particular could work against its trademark openness, ‘unorthodoxy, opposition, and surprise’ (2017: 31).

- 32.

Matthew Philpotts laments the lack of theoretical categories for classifying periodicals, however, and proposes that periodical studies reach for new conceptual tools for more adequate ways of describing their distinctive formal properties. See Philpotts (2015).

- 33.

As Brooker and Thacker point out, however, notwithstanding their consciously limited readerships, such magazines, in the context of the Americas especially, could nonetheless be expansive in their reach, both in the sense of their widely dispersed regional locations of production as well as in their transnational, even transatlantic, distribution and circulation.

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.