Advertising has a historical association with tourism and periodicals: in the first, it has played a formative role in popularizing destinations, while in the second, its potential to subsidize the costs of publication has long been recognized. 1 Notwithstanding their ubiquity and multiplicity in the promotional apparatus of tourism, advertisements have received little scholarly attention in those arenas to date for a number of reasons. The oversight is due in part to a historical privileging of the status of the written over the visual text; in part, as David Hummon suggests, because ‘of a continuing … cultural bias against taking matters of leisure [tourism] seriously’ (1988: 180); and in part also due to a lack of established or shared methodologies in interpreting such material within and across the still emerging and expanding fields of tourism and periodical studies . Although images are often described and criticized by scholars (the most common forms studied being photographs, postcards, and posters), William Feighey’s complaint that ‘there are many forms of visual evidence available to researchers that are not [yet] apparent in the tourism studies literature’ (2003: 76) remains valid within and beyond that discipline. Advertising has been embedded in the pages of magazines of many kinds (and the press more widely) since the late nineteenth century, if not before. It has taken myriad forms, whether in advertising features/spaces proper; so-called ‘advocacy’ or ‘institutional’ advertising (in which the distinction between information and persuasion is ill-defined); or else, ‘in the adoption of [promotional and/or aesthetic] strategies drawn from the practices of commercial publicity to promote the periodical’ or in a ‘rhythmic interchange between visual images used for articles and … advertisements’ (Thacker 2010: 8, 14). Yet the taint of leisure, commerce , and familiarity has meant that ‘advertisements are narratives that are [still] rarely held up for scrutiny’ (Rogal 2012: 55) in periodical studies more widely and even less frequently understood as complex, diverse, and indeterminate texts in their composition, dissemination, and reception. Recent work in modernist studies, however, which has started to shed light on the imbrication of modernism and commerce (and its attendant dilemmas) precisely through a focus on advertising in little magazines , offers a useful template for work on this subject in different forms of print media. 2

This chapter seeks to add to the scholarship addressing that deficiency through a consideration of tourism advertising in Mexican Folkways (1925–1937), a renowned bilingual periodical designed to describe Mexico’s folklore and indigenous heritage, which has since become a treasured, if only partially read, source in the historiography of the country’s post-revolutionary period. Drawing on recent scholarship in tourism and periodical studies as well as Mexican cultural history, the chapter’s first two sections combine formal and thematic discussion of the magazine’s advertisements for El Buen Tono cigarettes and Mexico City hotels with findings from archival research that provide a fuller appreciation of both the genesis and diffusion of the title and the historical context in which they appeared. An exclusively text-based or semiotic analysis of such advertisements, while useful and part of the present study, has limitations that can be forestalled by this kind of multi-method strategy, which addresses the complex political, socio-economic, and aesthetic transactions at stake in these visual and narrative representations, which have been ‘long regarded as ephemeral and seldom archived ’ (McFall 2004: 154). 3 Indeed, as Liz McFall points out, only such a historically situated focus on the context of advertising production (which ‘has actually been much neglected’ by scholars) can provide evidence for considerations of advertising’s broader operations and influence as ‘a constituent material practice in which the “cultural” and the “economic” are inextricably entangled’ (McFall 2004: 5, 7). The advertisements under consideration here offer examples of some of the more frequent and conspicuous advertisers in Mexican Folkways . Analysis of these, which have been selected from a comprehensive survey of the magazine’s issues, enables a synchronic and diachronic perspective on the aesthetic practices and politics of advertising in modern Mexico. More specifically for the purposes of this book, insofar as they promote two kinds of consumer goods closely affiliated with the industry, the selected advertisements also have a direct correlation to tourism. As such, they speak to the fundamental affiliation between consumption and the geographical imagination, which in this instance is underpinned by an investment into these goods’ (far from simple) symbolic meanings as ‘exotic’. In this respect, the chapter responds to Robert Scholes and Clifford Wulfman’s proposal that we ‘learn to read advertising [in the magazine], to decode the images as well as the texts for both ideological and aesthetic purposes’ (2010: 140).

Attention to such paratextual features, this chapter contends, illuminates some of the central paradoxes at stake in the character of and reliance on Mexican Folkways as source material, tensions that resonate with others regarding the new Republic’s ostensibly counterintuitive endeavour to deploy tourism as a means of recovery and reconstruction after the Revolution . That is, an examination of tourism advertisements in Folkways illuminates in the periodical form what elsewhere Shelley Garrigan has called ‘the dialectical embrace of patrimony and market’ (2012: 4) and sheds light on untold stories of recycling of processes and stakeholders that had been fundamental to nation-building during the Porfiriato in the making of modern Mexico after 1920. The chapter aims to move beyond a reiteration of an already familiar story about Mexico during that more recent period of nation-building: that is, as Thomas Benjamin sums up, that ‘the cultural revolution, like everything else in Mexico during the 1920s and 1930s, was full of contradictions’ (Beezley and Meyer 2010: 449). 4 This chapter does indeed illuminate a range of such incongruities. In addition, however, it perceives advertising as part of the country’s wider visual culture —as much as the work of Diego Rivera , José Clemente Orozco , and other artists that Mexican Folkways advocated and reproduced in print—insofar as it speaks of similar issues and concerns being articulated on a larger creative and political canvass. A consideration of the magazine’s advertisements reveals a series of fascinating, sometimes seemingly incongruous encounters between tradition and modernity, art and commerce . It also has important historiographical and methodological implications that are addressed in the chapter’s final section through a consideration of the advertisers’ aesthetic and commercial histories.

I

To integrate Mexico. To incorporate into the Mexican family the millions of Indians: to make them think and feel in Spanish. To incorporate them into that type of civilization that constitutes Mexican nationalism . (3:1, 1927, 50)

In the magazine’s conception and execution, Toor was also influenced by the new methods and work of Manuel Gamio, who had led the excavation of Teotihuacán, and the anthropologist Franz Boas , under whom Gamio studied for his PhD at Columbia University, in a decade that inaugurated a strong and lasting tradition of cooperation between scientific researchers and institutions of the United States and Mexico. 7 Their work proposed studying indigenous traditions and local productions ‘con el fin de alentar la integración racial y la afiliación a un programa modernizador que buscaba la asimilación de los elementos “artísticos” a un nuevo sistema cultural’ [with the aim of encouraging racial integration and affiliation to a modernizing programme that sought the assimilation of ‘artistic’ elements into a new cultural system] (Albiñana 2010: 254). Boas repudiated prevailing Darwinist thinking about ‘racial type’ and hierarchy, for example, and proposed that races were mixed and unstable, the difference between binaries of barbarism and civilisation minimal: he urged Gamio to use his government post as inspector general of archaeological monuments to enable the study of Mexican folklore. Toor invoked both men as mentors and guides in the magazine’s first issue, recounting that ‘[Gamio] says that this is the first publication which will present the masses of the Mexicans to the American people’ (Folkways, 1:1, 1925, 1). Further, although she had intended originally to publish exclusively in Spanish, it was on the advice of Boas that Toor decided also to publish in English. President Plutarco Elías Calles subsequently praised the periodical for ‘making known to our own people and to foreigners the real spirit of our aboriginal races and the expressive feeling of our people in general, rich in beautiful traditions’ (López 2010: 104).

The magazine’s subtitle—Legends, Festivals, Art, Archaeology—synthesizes much of its content, which covered Mexican modalities of expression including the calavera, the corrido and the jarabe, but emphasized variations in tradition, language, and culture across the country. Articles ranged from ‘Costumbres mazatecas/Some Mazatecan customs’, ‘Marriage in a Maya Village’, ‘Modern Serpent Beliefs in Mexico’, to others on ‘The National Orchestra of Mexico’, and on the paintings and drawings of Mexican primary school children. 8 For example, in vol. 5, no. 1 (1929), the magazine published a popular corrido about the quashing by government forces of the Escobar rebellion in Chihuahua, while an earlier, anniversary issue (2:2, 1926) reproduced a series of turn-of-the-century lithographs, portraying lurid tales and newsworthy events, such as murders by women, scandals in the clergy, and the advent of the electrical tram. Other features in the magazine singled out particular aspects of the national character or local symbolism. Anita Brenner , for example, in the magazine’s inaugural issue, perceived the petate as a ‘spiritual tradition’, whose ‘intimate relation to the eternal verities … is a perfect basis for a national philosophy’ (1:1, 1925, 15); while Manuel Hernández Galván depicted the ranchero as ‘a born artist for … song’ (1:1, 1925, 8). As Luis Anaya Merchant avers, separating out its ‘descriptive realism’ from a Porfirian aesthetic and imaginary, Folkways ‘era como tener una suerte de laboratorio de acceso al pasado’ [was like having a kind of laboratory to access to the past] (Elizalde 2007: 131). The same is true of the magazine’s sustained emphasis on music, whether in transcribing the lyrics of corridos or printing the musical scores of the same popular and other song forms from across the Republic’s repertoire. Folkways thus speaks eloquently to Carolyn Kitch’s assertion that magazines are ‘the most dialogic of all journalistic media’ (2005: 9). It is not only that Folkways was engaged in the exposition and dissemination of Mexican folklore to an international readership through articles such as those already mentioned, as well as through other visual and discursive mechanisms, including its responses to readers’ letters, enquiries, and suggestions. In making material available from Mexico’s national folk repository to a mestizo, metropolitan audience, the magazine facilitated intercultural encounters between attributed and unattributed contributors and readers from across class and ethnic divisions within Mexico’s own frontiers as well as from either side of the Mexico–US border. As such, it consistently encouraged interaction between readers, content, and ‘tradition’ through processes of collective participation and creative performance. In a thematic and formal sense, Folkways was a dialogic, dynamic archive of Mexico’s artistic and creative expressions.

Front cover of Mexican Folkways, 5:1, 1929

The magazine’s ethos and its status as a transnational cooperative proved to be its strengths but also ‘its points of vulnerability’ (López 2010: 104), however, as its funding was subject to the vicissitudes of Mexico’s volatile political culture. The periodical’s subsidy was withdrawn after Gamio’s departure from the SEP following his attempts to expose the corruption of his supervisor, José Manuel Puig Casauranc. Puig Casauranc, with Saenz (who was appointed to fill Gamio’s vacancy) later reinstated the grant, on the appeal of the poet José Frías, and eventually covered the entire costs of the magazine’s production (López 2010: 104). The magazine’s schedule and size speaks to those changes in fortune. Folkways originally appeared in 7 × 9.5-inch format, with some fifty or more pages of content. From the third issue onwards, however, it had grown not only in reputation but also in dimensions, to 9 × 11 inches, and in page numbers to an average of seventy, a larger and longer format enabled, no doubt, by the commercial advertising it also took from that point onwards, which appeared on its inside front and back pages and covers. The magazine also operated on a reduced publication schedule. For the first two years of publication, 1925–1927, Mexican Folkways was published bimonthly and from 1928 to 1933 every three months, with a suspension in 1932. Things changed drastically in 1931, when the Departamento de Monumentos Artísticos Arqueológicos e Históricos (DMAAH) took charge of all state-funded cultural institutions. As part of its mission to challenge foreigners’ domination of social and cultural research in Mexico, it cut off all support to Toor’s magazine, claiming that it was a foreign enterprise. Toor failed to secure funding for it north of the border, where the title was regarded as a Mexican, rather than a US project. In consequence, during its last four years of publication until 1937, only three issues of Mexican Folkways appeared, as monographic numbers on the Yaquí Indians, and artists José Guadalupe Posada and its ‘own’ Rivera .

the new governing classes have discovered the value of the Indian just as the Industrial Revolution has discovered the value of the man on the street. They have realized that if Mexico is to progress, the masses of Indians, forming two-thirds of the population, must be taken into account. (7:4, 1932, 206)

I did not take existing folklore magazines for models. As I wanted Mexican Folkways to express the Mexico that interested me so keenly, it has not only described customs, but has touched upon art, music, archaeology, and the Indian himself as part of the new social trends, thus presenting him as a complete human being. And in order that the magazine might mean something to the Mexicans as well as to outsiders, everything has been published in both English and Spanish… Because of my own joy in the discovery of an art and civilization different from any I had previously known, I thought it would interest others as well. (7:4, 1932, 208)

Notwithstanding the tribulations involved in its launch and editing (her complaint that ‘I have been willing to do many hard and disagreeable things’ is expressive of the travails of many little magazine editors of the period [7:4, 1932, 210]), Toor avowed that the magazine’s six completed volumes were ‘a fair document on customs and art’ and underscored the recognition it won from well-regarded scientists and subscriptions from ‘the best libraries in the United States and […] [is] esteemed even by those of the young Mexican writers who were not at all interested in the Indian’ (7:4, 1932, 209). The magazine’s archival and pedagogical objectives for students of Spanish as well as for readers with a general interest in folklore anticipated at its very beginnings had thus been accomplished in Toor’s eyes. Further, notwithstanding its own lack of precursors and averring that ‘there is [yet] nothing so complete’ (7:4, 1932, 210), Toor went on to advocate Folkways as a ‘human and scientific’ model for a pan-American magazine on the same subject matter, which ‘would be of great value socially and artistically’ (7:4, 1932, 211).

Alongside its spearheading of Mexican folklore, Folkways also placed strong emphasis in its content on contemporary visual culture . Throughout its lifetime, the magazine was a veritable compendium of images by numerous photographers such as Tina Modotti, Edward Weston, and Toor herself. There were too, in addition to reproductions of the photographs of Modotti and Weston , features on individual Mexican artists, centrefolds, and distinctive collectable front covers by Rivera . In this respect, Folkways could well be regarded, like many of its ‘little’ Anglophone counterparts, as an ‘advertising house for individual modernists, as well as modernism itself’ (Thacker 2010: 8), a promotional objective that fundamentally belies the time-honoured distinction between art and commerce in myriad ways, as discussed further in later sections of this chapter. Indeed, the magazine was the first outlet for the publication of Modotti’s essay ‘On photography’. In that piece, illustrated by a reproduction of her 1929 photograph ‘Woman of Tehuantepec’, Modotti disavows the category of art for photography, insisting that her main aim is ‘to produce honest photographs, without distortions or manipulations’ (5:4, 1929, 196). As Rubén Gallo points out, one of the reasons photographers insisted on their medium’s superiority over painting and ‘on its political significance during times of social revolution was [precisely its] capacity to produce an accurate reproduction of reality’ (Gallo 2005: 13). In her essay, Modotti dismisses debates about whether photography is or is not art: the only important distinction, she says, is between good and bad photography, whereby the former takes into account the technology’s limitations as a medium while maximizing its potential as a modern tool par excellence, or, as she puts it, ‘the most eloquent, the most direct means for fixing, for registering the present epoch’ (5:4, 1929, 196). Modotti’s essay is a testament to a broader contemporary investment in Mexico in the power of technological developments—especially photography—to provide a radically new perception of reality; in essence, to revolutionize ways of seeing. Its publication in a periodical devoted to a new way of seeing the rural, the ‘real’ Mexico, is apposite.

Mexican Folkways, in its exaltation of the place and popular traditions of Mexico’s Indians in the new Republic, documented the two major currents of reform, or as Benjamin puts it, the ‘two revolutions within the Revolution ’ that began to arise in Mexico in the 1920s: the cultural revolution, the effort to create the new Mexican man and woman, and the social and economic one, to create ‘a nation of prosperous peasants and workers’ (Benjamin 2010: 449). Yet, in its sustained emphasis on the new, cosmopolitan visuality, the magazine also upheld what Gallo calls ‘the other Mexican Revolution … triggered by new media’ in the years after armed conflict, whose revolutionaries were artists and writers, fighting not with weapons ‘but with cameras, typewriters, radios, and other mechanical instruments … their goal … not to topple a dictator but to dethrone the 19th-century [anti-technological, modernismo-influenced] aesthetic ideals that continued to dominate art and literature in the early years of the new century’ (Gallo 2005: 1). The new visual technologies, photography especially, and the mass media, of which ‘print ha[d] the deepest roots in Mexico’s past’ (Rubenstein 2010: 600), together promised a direct and authentic record of the realities of Mexico after the Revolution, a befitting method both of documenting popular traditions and of providing a means for people to understand their new circumstances. While scholars have long invoked and acknowledged the significance of the magazine’s subject matter, the following section considers a further, hitherto unstudied, aspect of its innovations: the regular inclusion of advertising .

II

Americans ran most of the fifteen thousand miles of rail that carried exports to Gulf ports and US border towns and hauled foreign merchandise back to Mexico City … streets were paved, sewers were laid, and lights were installed by American, Canadian, German, and English firms. And Spanish, German, English, and French businessmen owned the city’s department stores, most of its grocery, clothing and hardware businesses and its slaughterhouse and meatpacking plant. (Johns 1997: 17)

Notwithstanding, commercial advertising gained legitimacy among the Porfirian elites as the consumption of brand name products became associated with specific ideas and where ‘definitions of social norms and the ideal image of a modern Mexico centered around the act of consumption’ (Moreno 2003: 86). Within this context, as large companies introduced brand names and new products in large half- or full-page notices in print, advertising, which had previously relied on simple text, modest size, and spacing (and tended to be ‘relatively dry and informative’, Rubenstein 2010: 602), started to incorporate new, sophisticated techniques and to use modern technologies such as photography as well as drawing. It was not until the 1920s and 1930s, however, that advertising began to be promoted more aggressively as an effective business practice among Mexican storeowners and provincial merchants, who had previously regarded it as improvident. In the post-revolutionary decades, modern industrial and commercial development once again began to be seen as the principal engines for economic growth; although this time an urban lifestyle and the consumption of advertised products became associated with ‘a new form of democracy , a “consumer democracy”’ (Moreno 2003: 2–3). As such, after 1930 there was a rapid expansion of ‘the number of commercial graphics, an expanding range of goods being advertised, and a shift in the rhetoric being used by advertisers’ (Rubenstein 2010: 602). Indeed, from the mid 1930s onwards, government officials at the National Secretariat of the Economy (SEN) coordinated various efforts to publicize the effectiveness of advertising in increasing sales and to legitimize its practice: these included establishing a national Day of Publicity (April 23) and broadcasting radio announcements to inform the public that advertising benefited the nation by encouraging consumption. At this time, Julio Moreno avows, ‘Advertising became synonymous with service to the nation’ (Moreno 2003: 25–26).

Mexican Folkways regularly ran commercial advertising from its third issue onwards, on its inside front and back covers and first and last inner pages, all of them high-status spots for advertisements. The magazine’s original advertisers—many of which subsequently became stalwarts in its pages—were the San Angel Inn, La Foto and the American Tobacco and News Store. Their advertisements consisted of half- and quarter-page notices while smaller retail outlets such as restaurants and others like the National University of Mexico Summer School took out ‘classifieds’. Many businesses, such as Agencia Misrachi (a Mexico City store selling foreign magazines and newspapers), the department store Sanborns, the Hotel Genève and Weston’s Mexican Art Shop (‘leading curio and souvenir house of the republic’), offered services of specific interest to a touristic audience. At a time when ‘National songs and dances [had] bec[o]me fashionable overnight, and every home had examples of the popular crafts, a gourd from Olinalá or a pot from Oaxaca’ (Delpar 1992: 12), these adverts form part of an explicit endeavour underway in those decades to market the ‘quintessentially’ Mexican abroad, particularly in the United States where the Mayan revival style was in vogue in architecture across California, for example, and Adolfo Best Maugard’s theories on creative design became available in English translation. 11 ‘Cultural’ and national advertisers readily associable with a ‘little magazine ’ of this kind such as (foreign language) bookshops, art galleries, Talavera de Puebla pottery, the National Lottery, and, fittingly, though perhaps uniquely, the Banco Nacional de Crédito Agrícola [National Agricultural Credit Bank], also featured in the pages of Mexican Folkways. 12

On the other hand, advertisements for construction and engineering firms, utilities and consumer goods belong to a discrete category of adverts speaking to a broader codification of modern managerial efficiency, apparently at odds with the advertisement of ‘national’ goods already mentioned. 13 Consonant with the way in which visual culture involves ‘the things that we see, the mental model we all have of how to see, and what we can do as a result’ (Mirzoeff 2015: 11), these and other advertisements do more than promote individual products—they speak to shared aspirations at consumer and national levels. Thus, advertisements for Frank McLaughlin and Co., Compañía Mexicana de Luz y Fuerza, Chapultepec Heights, Kodak and Frigidaire are about ‘the consumption of advertised products, an urban lifestyle, and the modern industrial setting’ (Moreno 2003: 2–3) all of which, as Moreno has pointed out in his study of business culture in Mexico, were associated with national progress and material prosperity in Mexico’s postrevolutionary reconstruction. At a time when advertising ‘[was] a key feature of urban modernism’, electricity, radio, photography , and property investment—all regularly advertised in Folkways—signified not only ‘keys to sustain the vitality of a busy, energetic people’ but also ‘idioms for the celebration of energetic ambition’ (Lears 1994: 180). For example, Kodak presents itself in Folkways, underneath an advertisement for the Mexico City photographic shop La Foto, as ‘do[ing] better work’, its spatial positioning and rhetoric redolent of the long-standing colonial asymmetry in north–south relations. Meanwhile, in a similar vein, an advertisement for Frank McLaughlin’s construction company lists myriad services on offer (‘designs – estimates – reports – appraisals’) for the budding North American settler. That the opportunity for partaking in and of such activities, utilities, and services is publicized repeatedly in the magazine signals to its readers that the new Republic is ‘open for business’ and that, in addition to its distinctive art, folklore, and legends, the country shares or can enable similar determinations as those of its northern neighbor in terms of efficiency, modernity, and material progress.

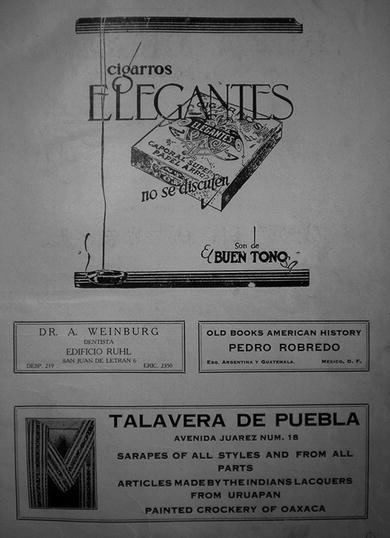

Elegantes advertisement, Mexican Folkways, 3, 1927

The advertisement comprises elongated lettering announcing the brand while the caption (‘No se discuten’ [They’re indisputable]) is superimposed on the image of a cigarette packet, the product/signified here merging with its correlative, or the sign, itself. The entire picture is framed by a vertical whisper of smoke from an ignited cigarette resting on an ashtray in the lower left-hand side of advertisement, connecting a corrugated frame at its head and foot. That smoke trail and those linear, willowy calligraphic forms—alongside the exaggerated flourish of the letter G of cigarros, and the ‘de’ of ‘Son de El Buen Tono’ in the advert’s lower right hand side—speak to contemporary ‘art deco’ design (an international ‘form of modern minimalism’, Hammill and Smith 2015: 89) and also recall the shape of the very product being advertised, correlating aesthetic and product in their common, cosmopolitan modernity. The absence of any human figure and the cigarette’s angle in the ashtray, which is positioned in the advert’s outer frame, invite the participation of the reader/spectator: they point to an internal absence that ‘anticipates the receiving subject’ and also imply a narrative of some kind. The lit cigarette indicates the (albeit short-term) absence of a smoker (and raises a number of questions: ‘Who are they?’, ‘Where have they gone?’, ‘What interrupted his/her smoking?’); it indicates an absence into which the reader can merge and take ‘his’ place (and, as I shall clarify below, it is likely to be a he), to savour that elegant, fine-tasting, smoke.

Número 12 advertisement, Mexican Folkways

Once again, as in the case of the Elegantes advertisement, the emphasis is on the cigarette’s high quality, on discernment and on the appellation of the reader as a unique and special individual, as already part of a clique of consumers with knowledge, good taste and propriety, the latter qualities crystallized in the tobacco company’s own name, which was taken from an expression to refer to good familial pedigree and manners. 15 Though relatively economical in their visual language, to be sure, these advertisements yoke this cigarette brand to notions of leisure, sophistication, and style, portraying it, as Bunker puts it, ‘as the ticket to a dream world of success for which most of their consumers could only puff and pray’ (Bunker 1977: 237). That El Buen Tono cigarettes were marketed as abbreviated forms of diversion and respite is illuminating for, as Jackson Lears notes in his cultural history of advertising in America, by comparison ‘the pace of cigar smoking [which had long been linked with relaxation] began to seem too leisurely for the pattern of life promoted’ (1994: 181) by advertisers in the early decades of the twentieth century. Indeed, in the late nineteenth century, as Susan Wagner documents, cigarettes started to appeal to ‘a more prosperous and refined public than chewing tobacco and pipes had reached, or even cigars’ (1971: 34). This was due in part to their attunement to the tempo and character of a growing urban population and culture north of the Mexico–US border: ‘Tobacco supplied something romantic that was missing’ (Wagner 1971: 34). El Buen Tono’s adverts speak to a further issue of concern in Mexico, that is, the development of taste, which historically ‘lagged behind the growth of wealth’ (Johns 1997: 31). The cigarette manufacturer’s name, branding, visual and rhetorical language all supply, in different but complementary ways, style, discernment, even good health (for while the phrase buen tono is best translated as ‘good upbringing’, tono can also mean tone). 16 The cigarettes’ marketing as such to United States—and, importantly, also Mexican—consumers in the Folkways advertisements is belied by a fundamental irony, however: the qualities of respite and ‘tonic’ they offer in Mexico, a destination sought after by the tourist for the authenticity and exoticism (particularly) of its native peoples and history, were all under threat precisely from the very modernizing processes the country was also then embracing.

Los recorridos [del dirigible] unían el espacio empresarial con el público multitudinario y ofrecían una visión del futuro. La empresa se colocaba en ese horizonte y los consumidores podían ser trasladados de su presente – convertido en un pasado rebasado por la modernidad – para compartir ese porvenir que estaba entre las nubes. (Hellion 2011: 19)

[The (dirgible’s) trips brought the business world and mass public together and offered a vision of the future. The company was situated on that horizon and consumers could be transferred from the present – converted into a past overtaken by modernity – to share in that future in the clouds.]

In this light, the Elegantes advertisement in Folkways seems deliberately anachronistic. Its ‘art deco’ font aside, that the image in that advertisement is a line drawing, rather than a photographic reproduction, underscores its own handmade, ‘artistic’ origins. This connection is seemingly at odds with both the (actual, more general) promotion of the product’s modernity and the cigarette manufacturer’s own history (to which I return below), as well as the magazine’s prevailing interest in photography . Aesthetically, the obvious eschewal of a photographic image, which were in wide circulation and application in advertising at that time and in features elsewhere in the same magazine, in favour of the more time-intensive hand drawing, aligns the product with an economy of making. Indeed, if ‘the technique of reproduction detaches the reproduced object from the domain of tradition’ (Benjamin 1999: 215), the advert’s reliance on the hand drawing rather than mass-manufactured photographic image fundamentally reattaches the cigarette to the kind of manually produced indigenous craft traditions and artisanal practices that are the predominant subject of interest elsewhere in Folkways. The advert’s aesthetic insistence on the handmade and non-mechanical thus befogs the division between the artisanal and the commercial and implicitly aligns the product with other local productions depicted in the magazine (pottery, textiles, masks, jewellery), emblems all of Mexicanness in some way. At the same time, it invests this design and, by extension, the tobacco product with an aura of recreation, independence, and privilege. In this respect, the advertisement anticipates what Arjun Appadurai calls production fetishism, which rests on the illusion of romanticized forms of local production and national sovereignty. Depicting its brand(s) as consonant with the kind of tradition promulgated by Folkways and sought after by tourists visiting Mexico clearly serves the tobacco manufacturers’ purpose: in this instance, El Buen Tono’s tobacco product offers timeless, ineffable ‘tradition’ as respite from the rapid pace of Anglophone modernity, as well as a souvenir to recreate that experience back home.

In light of El Buen Tono’s particular expertise in publicity as well as of the spectacular character of advertising, periodical, and the wider visual culture of that period (and, notwithstanding the company’s long-standing dependence on lithography, that technical circumstances do not appear to have been a limiting factor at stake in this case), it is not unreasonable to deduce that the (extra)ordinary style of these adverts is a result of an accommodation to the agenda, objectives, and ‘tone ’ of Folkways itself. Folkways was not a mass circulation publication, like Revista de revistas : it appealed to a literate audience and therefore advertisements carried in its pages did not need to rely on visual composition alone, though economic factors will also have been at play too. However, a more vivid, expressive promotional apparatus might have constituted a visual misdirection from the magazine’s main features and ‘serious’ outlook, the professional photographic images of which might reasonably have curtailed the ambitions of a staff artist in El Buen Tono’s employ. It is noteworthy that, in comparison, other contemporary ‘little’ magazines in Mexico at this time carried either little or no advertising, or had advertising specifically tailoured to their readerships , while populist publications such as Revista de revistas were replete with them. The literary magazine México moderno , for example, which ran from 1920 to 1923, published notices only for itself, other germane magazines (e.g. Revista musical de México ), Steinway pianos, and classifieds for professional music teachers, or for a limited range of what were then deemed modern national goods, including beer (Toluca Extra and Victoria) and gasoline (Naftolina). 21 There is more to say about the implications of El Buen Tono’s advertisements in this chapter’s concluding section.

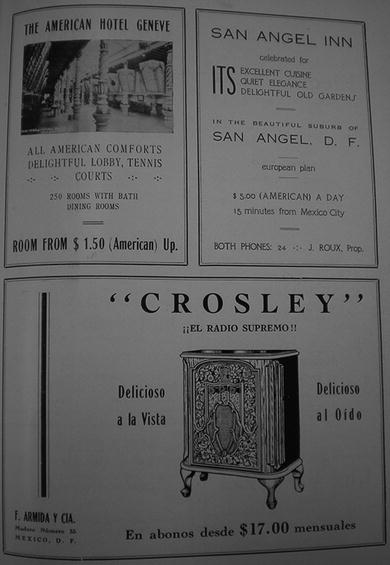

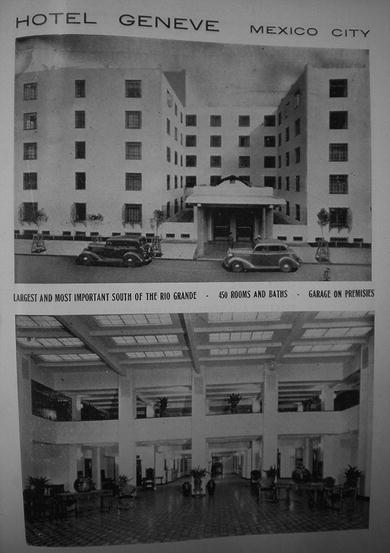

Hotel Genève advertisement, Mexican Folkways, 3:1, 1927, p. 1

Notable here, as in the previous example of the Elegantes cigarettes advert, is the inclusion of captions and the absence of human figures, in this case in a side-angled photograph of the hotel lobby, which visually captures its voluminous proportions and generous interior space. In underlining its ‘American comforts’ and potential for familiar leisure activities such as tennis, the advert’s captions, like the photograph, work to contain risk; promoting known sporting pastimes as well as recognized spatial arrangements was and remains important for tourists in an unfamiliar environment such as a foreign country (Clancy 2001: 74). However, the camera’s point of view sets up a dynamic, forward-moving trajectory, redolent of a classic modernist/futurist perspective, but symbolic also of the aspirations of the industry the advert promotes.

Hotel Genève advertisement, Mexican Folkways, 9:1, 1937, p. 1

Captions in a broad, clean sans serif font celebrate the hotel’s recent expansion to 450 rooms, bathrooms, and garage and underscore the hotel’s superlative size and significance, as the ‘largest and most important [hotel] south of the Rio Grande’. Each of this advertisement’s photographs, unpopulated by human characters with the exception of two barely discernible figures at the hotel’s entrance in the upper image, provide expansive, frontal views of the building’s vast proportions and fabric. The focus on the hotel’s obviously concrete construction highlights its modernity, for as Gallo explains, as an inexpensive and modern building material, cement, like photography , gained popularity as another ‘new’ technology during the 1920s. It was regarded as ‘efficient and forward-looking’, a building material that articulated a clear break with the [marble-dominated] architecture of the Porfiriato , and soon became ‘the perfect substance for building the new Mexico envisioned by the postrevolutionary government’ (Gallo 2005: 172).

The neat geometric lines of the hotel’s architectural design and its modern construction materials are thrown into relief, however, by other details in both images: trees and plants placed in linear arrangements on the pavement outside the hotel’s entrance and in strategic patterns in the vestibule and mezzanine of its interior, which is in turn furnished with heavy, colonial-style wooden tables and chairs. As Krista Thomson points out in another context, in the tourist industry such an instance of or a gesture towards ‘tropicalisation ’ (here, in flora and furnishings), based on reconstructions of the country’s past, in fact became more broadly a ‘forward-looking project for … [post-colonial] elites’ (2006: 12–15), valued paradoxically for the modernity it could bring about in terms of attracting tourists and their capital . In contrast to the fussy-ness of the historic 1929 image of the hotel on its website, where the ornate carvings of the vestibule’s columns, abundant plants and intricate glass details connote more typical and abundant tropical elegance, the full-page advertisement in Folkways is more sparse and vacant and emanates a futuristic quality. 23 That is, the tropical, neo-colonial revival is contained, while the solidity and orderliness of the modern architectural design and construction promise class, style, and consolation to the foreign tourist. 24 That advertisement’s tamed and domesticated version of nature and tradition indicates to potential tourists safety, discipline, and order in the foreign environment: in effect, to draw further on Thomson’s suggestions in the germane setting of the Caribbean, this is a ‘visual treatment of the effectiveness of colonial rule and naturalized colonial and imperial transformations of social and physical landscape’ (2006: 7). The vacancy of that image of the hotel, like the absence of the smoker from the El Buen Tono advert, also betokens a potential narrative, beckoning an implied reader/tourist in a search of ‘authentic’ experience but clean, modern accommodation. Though it is true that vacancy of a similar sort featured in much contemporary modernist photography of Mexico City (an urban landscape, Tenorio Trillo claims, that when photographed seemed devoid of people or only ever populated by poor brown bodies), in this tourism advertisement that absence has a particular freight. 25 The advertisement, like a blank slate, invites the reader to occupy a place in the hotel’s empty spaces, including its ‘delightful lobby’, which is devoid of other residents, staff, or any undesirable elements. The historic associations of other visual representations of blank spaces, such as those on maps for example, with (colonialist) expansion and incursion are also resonant here (for more on which, see Chapter 3). Yet, the vacancy is also redolent of a fundamental illusion: that is, the lobby offers ‘only simulacra of unity and reconciliation’ (Flaherty 2016: 106) for ‘the togetherness in the hotel lobby has no meaning’ (Kracauer 1999: 291). Although this advertisement’s aesthetic choices are at odds with those of the retroactive hand-drawn adverts for El Buen Tono cigarettes, the implications are commensurate. The modern medium of photography , in which Folkways was so invested and ardently promoted, is critical to this: ‘serving [itself] as a form of discipline’, photography selected what was fit to be represented and ‘offer[ed] an additional degree of assurance to travellers that “the natives” and the landscape were tamed, safe, and framed for their visual [ultimately material] consumption’ (Thomson 2006: 17).

The coupling of cultural ‘authenticity’ with a ‘first-world’ hospitality experience has long been a consideration for designers and architects in Mexico: indeed, as Luis M. Castañeda points out, the standards for hotel design were set precisely in the 1930s, more or less contemporaneously with the publication of the Folkways advertisements for the Genève discussed here. Those design standards were established by the Mexican Automobilists Association (AMA), one of the country’s earliest tourist associations, which ‘called for simultaneous inclusion of “traditional” and “cosmopolitan” cultural references’ in hotel construction (Castañeda 2014: 175). An adjacent advertisement on the same page of that issue of Folkways for the San Angel Inn reiterates that incongruous juxtaposition (see Fig. 3.4). A more traditional architectural and geographical prospect than the Genève, as it was converted from an old mission-style convent in the outskirts of Mexico City, the San Angel Inn advert (here as in other issues of the magazine) relies on captions to promote similar qualities. The tropical, exotic, and exclusive are recalled in references to the hotel’s cuisine, elegance, and ‘delightful old gardens’ while its simultaneous modernity is addressed in the announcement of a European plan (where for the tourists’ convenience the payment was for room and breakfast only, with other meals to be taken outside at extra cost) and articulated visually through the use of a contemporary font for the advert’s lettering (Fig. 3.5).

III

What can such advertisements tell us about Mexican Folkways and, more broadly, Mexico during that dynamic period of nation-building after the Revolution ? First, that the magazine took commercial advertising tells us something about Toor’s ambitions and pragmatism as an editor . While she may have boasted about the magazine’s independence—that it was published in Mexico City ‘without any subsidy from a folklore society or rich benefactor’—the SEP subsidy was precarious. Commercial advertising enabled an additional income stream (it no doubt contributed to an increase in size and page numbers, as well as better quality paper in later issues), but even in an era where the relationship between the intellectual and state was close, albeit still unpredictable, it will also have betokened precious editorial autonomy. Second, if adverts for hotels , newsagents, and souvenir shops were targeted more obviously to tourists north of the border, the cigarette adverts also help us understand something more specific about the magazine’s ‘national’ readership , notwithstanding the ‘impossibility’ of historical reconstruction of origins in this respect. 26 Of the many brands produced by El Buen Tono , the two promoted in Folkways—El Número 12 and Elegantes—were specifically conceived for and marketed to young middle-upper class urban male consumers , a detail that gives us a clearer idea of the identity of (some of) the magazine’s implied audience in and outside Mexico, one which is consonant with the shifts in tobacco consumption identified by Wagner to which I referred earlier. Third, alongside the magazine’s dissemination of the country’s folkways and indigenous cultures, the advertisements in Folkways depicted Mexico City as a cosmopolitan place of progress and modernity; a lettered city, with refrigeration, safe and comfortable accommodation, ample opportunities for consumerism, property development, and investment. Such marketing might have been at odds with the periodical’s promotion of the country’s unique rich ethnic and folkloric diversity, but it spoke acutely to Mexico’s geopolitical aspirations. In short, in many ways these advertisements distilled one of the central fantasies of the Revolution , pithily summed up by Horacio Legrás: that ‘the whole past was open to appropriation and the whole future to construction’ (2017: 123).

Cigarettes and hotels provide instructive case studies of goods that were marketed precisely in seemingly dichotomous but overlapping terms of ‘tradition’ and ‘modernity’. Moreover, their histories as goods speak to a revival or continuity of processes, stakeholders, and rhetoric that had been fundamental to nation-building during the Porfiriato in Mexico’s post-revolutionary reconstruction. One of the ironies of the association between Folkways and El Buen Tono, for example, stems from the company’s own transnational history. One of the most long-established tobacco companies in Mexico, El Buen Tono became well known for its French-style cigarettes and for its pioneering modernization of cigarette manufacturing. The company grew from humble, artisanal beginnings to become one of the largest enterprises in the country, a rise due in part to its political connections both under Díaz and post-revolutionary governments. Indeed, El Buen Tono was considered ‘un modelo del ideal porfiriano del progreso’ [of model of the Porfirian ideal of progress] (Camacho Morfin and Pichardo 2006: 89): Díaz attended the opening ceremony of the company’s second site in May 1897, as did the opera singer Emma Calve in 1908, after whom it named one of its lines, and Porfirio Díaz Jr. sat on its board of directors (Haber 1989: 100). In its seventy-seven years of operation, El Buen Tono manufactured dozens of different cigarette brands, among them Héroe de la paz, a line conceived in homage to, and with an image on its packaging of, Díaz. 27 The company’s founder, the Frenchman Pugibet, whose residence in Cuba equipped him with the necessary expertise about the cultivation of tobacco and cigarette production, migrated to Mexico in 1879, it is thought, in response to Mexican government efforts at that time to attract foreign investors to participate in the country’s development. Financed by a substantial family inheritance bequeathed to his Mexican wife, Guadalupe Portilla, who also worked in the company in its early days, Pugibet introduced new technology to cigarette manufacturing in Mexico, which also enabled his company’s monopoly of the industry for many years. For example, in 1885 he patented machines to package cigarettes more rapidly and in 1889 introduced into his factory Decloufé machinery, which effectively brought the cigarette’s traditional handmade manufacture to an end. By the end of that year, Pugibet’s factory was producing over three and a half million cigarettes daily. Indeed, that this ‘undisputed giant of the cigarette industry’ effectively quashed small-scale artisan cigarette production in Mexico illuminates the material as well as ideological paradox of its hand-drawn aesthetic in the Folkways advertisement discussed above, which exalted the handmade and the local just as (or indeed even because) the company was modernizing and internationalizing at such an expeditious rate (Haber 1989: 100). A business founded by a European trained in Cuba , funded by Mexican money, and facilitated by French technological innovations, El Buen Tono became an international success, its products and promotional campaigns winning various overseas competitions, and it was appointed as official supplier to the Spanish royal household in 1908. 28 The notions of modernity and leisure on which it traded, as seen in the discussion earlier, as well as the concern for hygiene (also advertising its Charros brand in Folkways, for example, as ‘suaves y agradables al más refinado fumador … higiénicos, engargolados sin pegamento’ [smooth and pleasant for the most refined smoker… hygienic, sealed without adhesive], 4:2, 1928, 76), were also all fundamental ideals of the Porfirian era that were nonetheless being rehearsed and recodified in the new Republic. 29

The Hotel Genève’s history is similarly telling in terms of the transnational and trans-historical interplay that underpinned Mexico’s postrevolutionary reconstruction, and which, ‘challenges the way [we] normally conceive of foreign and national and imperialism and cultural sovereignty’ (López 2010: 97). The hotel was modelled, as its name suggests, after the tradition of grand European hotels. It opened in 1907, in which year it was first photographed by the renowned German-Mexican photographer Guillermo Kahlo. Boasting a close connection with major historical events in Mexico, it was at the Hotel Genève where President Díaz dined with his family on the day that the Revolution broke out on 20 November 1910. The hotel continues to underscore its reputation as ‘a constant innovator in the Mexican tourist industry’, reaching back to its inception: it was the first hotel to admit unaccompanied single women as well as the first hotel in Mexico to offer a taxi service, telephone switchboard operators, dry cleaning, a travel agency, elevators, as well as a bathroom in every room. Indeed, by 1930, the Hotel Genève was the only hotel in Mexico City considered to be first class, and ‘thus satisfactory for American tourists’ (Terry 1923: 235), by Frank Dudley, president of the United States Hotels Company of America, though he still regarded it then in need of extensive renovation. Thomas Gore , ‘an experienced hotel manager of international repute’ (Berger 2006: 41), refurbished the hotel in 1931, adding 180 rooms to the original 120 and installing en-suite bathrooms in all the rooms. As Dina Berger notes, Gore requested a tax exemption from the government on the materials he imported from the United States for that purpose (Berger 2006: 135). Gore himself was part of the American colony that had first settled in Mexico during the Porfiriato and went on to become a member of a group of influential American developers and bankers that, during a wave of rapid construction in the capital at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, ‘mobilized local capital to push Mexico City beyond its colonial limits for the first time’ (Schell 2001: 53). Gore, for example, built some of Mexico City’s earliest apartments, Gore Courts and Gore Place, and he was a founding board member of the AMA, the group that set the standards for hotel design and construction for decades to come (Berger 2006: 51). Indeed, in many ways, the Hotel Genève’s promotion in Folkways anticipates the kind of issues that would dominate the construction of Mexico City hotels during the capital’s fateful hosting of the 1968 Olympics. Then, tradition and modernity, authenticity and cosmopolitan hospitality, came into dialogue once again in Ricardo Legoretta’s design for the Camino Real Hotel, an important convention centre for Olympic diplomatic events and host of prominent international visitors, among them the International Olympic Committee (IOC) President (Castañeda 2014: 176). In this instance, the hotel cited tradition rather than modernity in its building materials, Legoretta opting, instead of cement, for sun-dried brick in its construction, ‘a material used in pre-Columbian, colonial and modern-day “vernacular” buildings in several regions of Mexico’ (Castañeda 2014: 179) and rough plaster walls in the hotel’s common areas. As in the Hotel Genève thirty years earlier, however, the Camino Real’s décor included replicas and originals of colonial candlesticks and dressers, which ‘contrasted in jarring ways with the fully abstract forms of the hotel’s interior’ as well as the use of artworks by the internationally renowned Rufino Tamayo, ‘Mexico’s most sought after official painter’, who drew on pre-Hispanic and folk-art traditions in his work (Castañeda 2014: 175, 181). 30

To be sure, there is ample evidence in Mexican Folkways of what Shelley Garrigan , in her study of monuments and museums in nineteenth-century Mexico City, calls the ‘dialectical embrace of patrimony and market’, the latter a value system, she cautions, that ‘presents a potential threat to a community that is still in the process of defining itself’, not least to Mexico during its protracted process of nation-building after the Revolution . Yet, as Garrigan observes, and as the advertising in Folkways illustrates in unique ways, ‘the commercial subtext of Mexican patrimony was integral to the emerging national profile and in fact anticipated the negotiations that regional and national guardians of cultural patrimony would face in the context of globalization in the century to follow’ (Garrigan 2012: 123). Mexican Folkways functioned as a guide to the ‘new’ Republic for domestic and international readers alike; its editor and contributors, likewise, were cast as ‘modern discoverers of an unknown country’. In addition to constituting the kind of archival collection of Mexico’s art, legends, and folklore that Toor had envisaged, the magazine functioned in certain ways as a catalogue of said traditions and the country’s native peoples, but also of available goods and services.

To address this latter aspect of Folkways is not an attempt to diminish the magazine’s significance; rather, to redeem it from its prevailing function as mere source material, ‘strip-mined’ solely for discrete pieces of information or treated only for particular historiographical interest, rather than studied as a composite aesthetic or cultural object in its own right. Indeed, if one of the shortcomings of folkloric studies and endeavours (such as Folkways itself) is that ‘cultural goods - objects, legends, musical forms - are of greater interest than the actors who generate and consume them’ and thus ‘always a melancholic attempt at subtracting the popular from the massive reorganization of society ’ (García Canclini 1995: 151), then arguably Mexican Folkways has been subject in turn to an analogous procedure by scholars, who have neglected the processes and agents involved in its creation, in favour of a fascination with the periodical as product and source. This chapter has proposed reading Mexican Folkways as an ‘autonomous’ object of study, through an engagement with its visual and discursive material (and the interplay between their constituent parts, as discussed above) but also with its narrative trajectory, or, as discussed in the first section, the magazine’s own biography over a lifetime in print. To that end, this chapter has marshalled a multi-method approach corresponding to the complexity of the material at hand in order to bring to light the magazine’s hitherto unstudied paratextual features and to apprehend advertising as part of Mexico’s broader visual culture and history. If the preceding discussion has illuminated the porosity of boundaries between national and transnational conceptualizations of culture and the less than clear-cut divisions between pre-and post-revolutionary Mexico, the periodical has transpired to be an exemplary expression of the difficulties entailed in separating out different epochs, nations, media, and value systems. Horacio Legrás’s reading of the Revolution in terms of textuality offers a useful conceptual framework in this respect. Acknowledging the ever-expanding archive of/on Revolutionary Mexico (of which this book forms part), he argues that an understanding of the Revolution as textuality allows ‘the element of contiguity precedence over previous forms of relationship based on hierarchies’ since ‘in revolution, works, people and ideas are not contained by firm and established boundaries [but] enter into unexpected conjunctions and borrowings’ (Legrás 2017: 3). As a miscellany of material in discontinuous form, the magazine visually and materially choreographs that very conception of textuality. Indeed, if one of the much-lauded innovations of Mexican Folkways was its presentation in content of the ‘real’ Mexico as rural and indigenous (in chorus with nationalist ideas of the period), at the same time its commercial associations and engagement with the ‘new science’ of advertising also grounded the magazine firmly in urban modernity and implicated it fully in the business of shaping Mexico’s consumer-citizens and tourists in and outside of the new Republic.

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

McFall questions the validity of a purely semiotic approach to advertisements in her work. Acknowledging the critical fascination with adverts and what they have to reveal about societies, cultures, and economies, she asks whether it is ‘really adequate to found a critique that reaches far into the nature and organization of contemporary societies upon textual deconstruction of the meanings of advertisements?’ (3). In turn, Sinervo and Hill concur with the need to consider the economic and political factors at stake in visual representations of tourism from an ethnographic perspective, in order to avoid falling into the trap of ‘predictable’ essentialist identity politics (Sinervo and Hill 2011: 127).

- 4.

As Erica Segre has pointed out, the articulation of national narratives did not necessarily sit easily with different presiding governments’ ideologies over that period, or necessarily coincide with the views of ‘a mobilized, patriotic public’: ‘Nor did the intellectual or artistic community coalesce behind the banner of the civic-minded, declamatory aesthetic and exclusivity of an enabling mexicanismo’, she observes (Segre 2007: 88).

- 5.

As Legrás observes, the state ‘borrowed the eyes of painters like Francisco Goitia in the excavation of Teotihuacán or the eyes of a Rivera in the dissemination of its own credo through popular and rural education’ (2017: 11).

- 6.

Mobile teacher training units called cultural missions travelled to rural villages, established libraries and trained teachers. A system of rural secondary schools that provided room and board, education and training free of cost was also established by the Ministry of Education (SEP). Other educational initiatives included the publication of cheap editions of canonical books of the Western tradition, which were placed in small libraries throughout the Republic. By late 1925 there were more than 3000 libraries and over 200 federal rural primary schools, a system that continued to expand into the 1930s by which time (1936), there were more than 11,000 rural schools. A department of fine arts was established to encourage the plastic arts, music, and literature and artists such as José Clemente Orozco and Diego Rivera were commissioned to paint public murals, which glorified a multiethnic nation (Beezley and Meyers 2010: 450–453).

- 7.

For more on this see Delpar (1992). Gamio studied under Boas at Columbia University and became his protégé, his time in New York ‘coincid[ing] with a period of enthusiasm for Mexican archaeology and anthropology on the part of Boas’ (Delpar 1992: 97). Boas’s belief in the unity of indigenous New World cultures was a critical factor in his interest in Mexico and led to the establishment of the shortlived International School of American Archaeology and Ethnology in 1911. Toor herself claimed not to be a scholar but to be interested above all in contributing to a greater understanding of Mexico in the rest of the world. In a letter of December 1932 to the anthropologist Elsie Clews Parsons, she indicated that ‘I’m more than content to have won the respect of people like you, Dr. [Franz] Boas, Dr. Paul Rivet and others for folkways’ (cited in http://www.encyclopedia.com/women/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/toor-frances-1890-1956, accessed 22 March 2017). For more on Franz Boas and his legacy, see Maxwell (2012), Lévy Zumwalt (2013), and Whitfield (2010).

- 8.

For a complete index of the magazine’s content, see Boggs (1945).

- 9.

The nature of that collaboration began to change from the 1930s onwards, due to anxieties about US expansionism during the interwar years and the increase in US researchers’ activity elsewhere in the world (López 2010: 122).

- 10.

See Johns (1997).

- 11.

In cultural relations between the United States and Mexico after 1920, art was the most attractive aspect of postrevolutionary Mexico. Not only were all forms of Mexican artistic production exhibited and generally well received in the US, but, as Delpar observes, they were also rooted in the history and popular culture of Mexico: ‘the Mexicans seemed to have created what many members of the American art world were seeking: an authentically national mode of art’ (1992: 125).

- 12.

The National Agricultural Credit Bank was established by President Calles in 1926, ‘most of whose funds were absorbed by large landowners in the north’, among them the Sonoran chickpea farmer and later president Alvaro Obregón. It was reorganized in 1931 to assist cooperative societies made up of ejidos and small farmers and it extended credit to cooperatives for the purchase of seed, fertilizer, and farm machinery (Beezley and Meyer 2010: 461).

- 13.

As John Sinclair points out, ‘national’ advertisers are so-called ‘because of their capacity to produce, distribute and advertise their brands throughout a whole country [not because] they are “national” companies: many in fact will be found to be subsidiaries of the transnational or “multinational” companies … such as Ford or [Unilever]’ (1989: 4). Anne Rubenstein identifies four ‘broad and overlapping’ categories of advertisement during this period: direct translations of advertisements from foreign publications; those for products associated with revolutionary nationalism ; those that referred to modernity in terms of technological progress; and those for products associated with racial or regional pride (2010: 602–603).

- 14.

As Susan Wagner points out, tobacco is ‘a purely American plant’, its smoking originating in the coastal regions of Central and South America: ‘the oldest known evidence of tobacco use is found on a Mayan stone carving at Palenque [Chiapas] … in a bas-relief representing a priest blowing smoke through a long tube’ (Wagner 1971: 6). On cigarettes as luxury commodities, see Williamson (1978: 32–39). For more on alcohol in Mexico, see Toner (2015).

- 15.

As Gallo points out: ‘El Buen Tono was named after an old-fashioned expression, immensely popular during the Porfiriato, that is best translated as “good upbringing” and was used to refer to the impeccable manners and flawless social etiquette that was expected of “good families” in prerevolutionary Mexico’ (2005: 143).

- 16.

See Gallo (2005: 143).

- 17.

McFall helpfully advises against falling into the trap of considering adverts of the past as qualitatively different to those of the contemporary period, as having only a function to inform, rather than persuade (2004: 153–154).

- 18.

El Buen Tono subsequently ‘effectively became their corporate patron’ (Gallo 2005: 146). For more on this, see Gallo (2005: 141–156).

- 19.

For more on this see Bunker (1977: 237).

- 20.

See https://cinesilentemexicano.wordpress.com/2012/05/28/la-compania-cigarrera-de-el-buen-tono-y-el-cine-la-calle-de-mayo-28-2012/ (accessed 14 June 2016)

- 21.

As Thacker points out, advertisements for other magazines and for publishers ‘were often accepted on a “no cost” or mutual basis’ and as a result ‘did not bring in revenue as such’ (2010: 7).

- 22.

In Mexico, prior to WWII, the period of our concern, hotel owners and operators were mostly independent (many small and family-run) operations, until the arrival in the 1940s of pioneers such as Intercontinental and Hilton.

- 23.

http://www.hotelgeneve.com.mx/en/hotel-geneve/#prettyPhoto (accessed 26 July 2016).

- 24.

If in 1932 Brenner drew attention to the colonial décor of the Hotel (de) Genève, it continues to exalt its classical European style on its present website: ‘Our guests, while strolling the hotel, will discover interesting antiques and works of art that have been part of the history of this unique “museum hotel”’. See http://www.hotelgeneve.com.mx/en/ (accessed 26 July 2016).

- 25.

See Tenorio Trillo (2012: 168–207).

- 26.

The difficulty in reconstructing readerships is, as Will Straw has pointed out, due to the absence of ‘tokens’ such as advertisements, letters to the editor, or other references in popular culture to the reading of periodicals, which normally serve to specify readers . Quoted in Hammill et al. (2015: 8).

- 27.

El Buen Tono’s brands included Reina Victoria, Alfonso XIII, Country Club, Jazz, Campeones (for sportsmen), Canela Pura and Margaritas (for women). It made cigarettes for export to markets in Europe (e.g. La Parisienne) as well as for the mass audience (La Popular and Mascota), and it even produced a line of chocolate cigarettes for children, for the consumers of the future.

- 28.

In the late 1920s, however, after two decades of unparalleled success, the company suffered the effects of the world silver and oil crises, and for the first time in its history registered financial losses, so that it did not pay a dividend to shareholders. Increased competition from rivals such as El Aguila, which had been founded in 1926 with plants in Mexico City and Guanajuato, and a new taste for blonde tobacco products from North America also meant the start of a rapid loss of market share for El Buen Tono . As Stephen Haber points out, the company ‘either lost money or earned very little in every year between 1932 and 1937 … losses [which] were less than they had been during the late 1920s, when losses equalled 10–13% of capital stock per year’ (Haber 1989: 182). El Buen Tono was eventually bought by Tabacalera Mexicana in 1961. For more on the company’s economic history see Haber, Industry and Underdevelopment, passim.

- 29.

As Ricardo López-León has pointed out, hygiene became equated with modernity in illustrated advertising in print media after the Revolution. In ‘Science and Technology as Key Shapers of Modernity: Illustrated Advertising in Mexican Magazines and Newspapers (1920–1960)’, Paper delivered as SLAS annual conference, Birkbeck, University of London, April 2015. See also López-León (2009).

- 30.

That building’s low-rise layout, dominated by strong colours from a typical Mexican palette, was also redolent of ‘the planning principles of colonial-period haciendas and of monastic architecture more generally’ (Castañeda 2014: 180).

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.