We know better than to repeal our masculine systems.

—John Adams

The Patrilineal/Fraternal Syndrome we have described, so ubiquitous throughout recorded human history, is alive and well today. In many nations, reliance on male-bonded kin groups for security remains the norm. Indeed, nations might be placed along a spectrum according to how important this security provision mechanism remains, or as Mark Weiner notes, clan societies “range from stateless societies known as ‘segmentary lineage systems’ to modern societies in which a weak state has difficulty containing the forces of clannism. In some circumstances, they even exist in developed, centralized states.”1 In other words, just because a nation is democratic or authoritarian, rich or poor, or located in a particular region, may not be sufficient to tell us the predominant security provision mechanism in use by its citizens.

To probe whether reliance on extended male-bonded kin groups as a security provision mechanism is linked to worse outcomes for nation-states, we first must define how we gauge this degree of reliance. This is not a straightforward task; each nation’s situation is nuanced and complex, having its own idiosyncratic history, its own mixture of subnational groups, and its own contemporary trajectory. Thus, the attempt that follows should be viewed for what it must be at this stage: a first step that cannot do justice to all of the observable complexity and particularity of the nations of the world. Even so, the theoretical framework laid out in the first two chapters of this volume tell us where to start: with the situation, status, and security of women. To gauge reliance on male-bonded kin groups as the predominant security provision mechanism, we look for evidence of the Syndrome components outlined in figure 2.4 in chapter 2.

Many countries, even in the twenty-first century, have a fairly intact Syndrome-based society, meaning that the primary mechanism of security provision in the society is the patrilineal kin network.2 Weiner explains that plenty of seemingly modern states are, in fact, “founded on informal patronage networks” and “traditional ideals of patriarchal family authority.”3 In these states, “government is hijacked for purely factional purposes and the state, conceived on the model of the patriarchal family, treats citizens not as autonomous actors but rather as troublesome dependents to be managed. Clannism is the rule of the clan’s historical echo [and] often characterizes rentier societies.”4

Reliance on male-bonded kin networks as the predominant security provision mechanism within states may be open and overt, such as in contemporary Afghanistan or South Sudan, but this reliance may be present even in countries with centralized states. For example, Weiner argues:

A form of clannism likewise pervades mainland China and other nations whose political development was influenced by Confucianism, with its ideal of a powerful state resting on a well-ordered family, and where personal connections are essential to economic exchange…Likewise, the principles of clannism influence nations that long ago ceased to be organized along tribal lines but that still afford a prominent role to lineage or ethnicity, such as Bosnia, or that hold patriarchal family authority in especially high regard, such as Egypt.5

In addition, some countries are transitioning back to this reliance on male kin networks as the primary security provision mechanism after having moved away from that reliance in earlier time periods—we see this phenomenon in the post-Soviet Caucasus, for example. Explaining this regress toward the older security provision mechanism, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) notes about that region,

Clannism flourishes, and its negative impact on freedom and society become stronger, wherever civil or political institutions that protect rights and freedoms are weak or absent. Without institutional supports, individuals are driven to seek refuge in narrowly based loyalties that provide security and protection, thus further aggravating the phenomenon. Partisan allegiances also develop when the judiciary is ineffective or the executive authority is reluctant to implement its rulings, circumstances that make citizens unsure of their ability to realize their rights without the allegiance of the clan.6

In contrast, other societies are gradually moving away from the full Syndrome, such as we have seen in South Korea’s dismantlement of the patrilineal hoju system.7 Even in these latter societies, however, we still see some of the fundamental components present, meaning that it remains possible for the Syndrome to resurge in the future if conditions are right. For example, although Latin American countries in the contemporary era do not practice brideprice or dowry, the foundation of high levels of violence against women, even to the point of widespread femicide, combined with highly inequitable family law and property ownership, as well as greater human capital investment in sons, remains and continues to undermine national outcomes. Indeed, these factors of widespread, normalized violence against women along with inequity in family and personal status law are reservoirs for Syndrome resurgence in many countries that have moved away from the full-blown Syndrome.

Wherever we find a fuller expression of the Patrilineal/Fraternal Syndrome, we know that extended male kin groups have substantial power within society. This explains why more general indicators of gender inequality within a society are insufficient for our purposes. Indicators such as female literacy, or the representation of women in parliament, for example, do not tap into the reproduction of clan exclusivity. As another example, high female labor force participation may exist even in a society encoding most of the Syndrome. As the political scientist Lindsay Benstead notes, it should trouble us that Libya ranked so well on the UNDP’s Gender Inequality Index compared with its neighbors in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.8 The dimensions of that index, examining health, labor force participation, and political participation, are not tapping into the proximate mechanisms of household-level disempowerment of women. Even maternal and infant mortality rates are insufficient for our purposes, because it is entirely possible to encode the Syndrome and yet deploy the nation’s resources to significantly lower those rates, as we see in the Gulf states. The prevalence of child marriage for women, the prevalence of patrilocal marriage, and other indicators of such household-level disempowerment of women can better inform us whether the reproduction of male kin group exclusivity is taking place.

In this chapter, we first provide a global overview of the Syndrome and then explore each of its components in greater detail. In this broad chapter, we focus first on how each of these control mechanisms subverts the position of women. Then in part II of this volume, we propose and then test a theoretical framework linking the degree to which a nation encodes the Syndrome to worse nation-state-level outcomes on a variety of dimensions of national security, stability, and resilience.

An Overview of the Incidence of the Syndrome Today

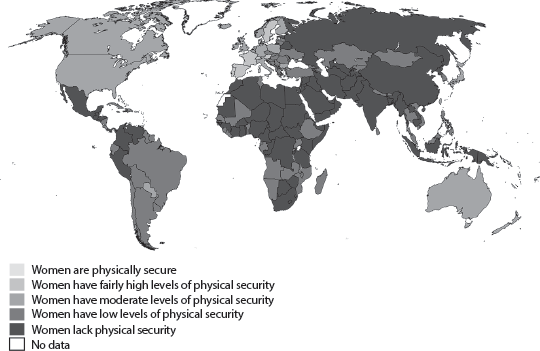

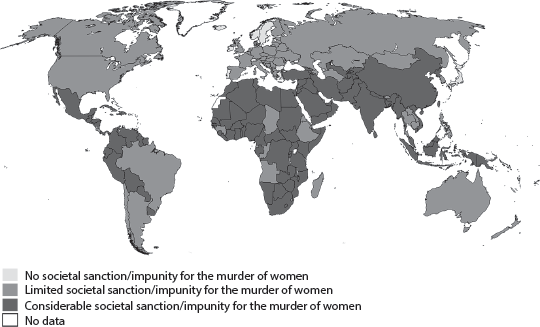

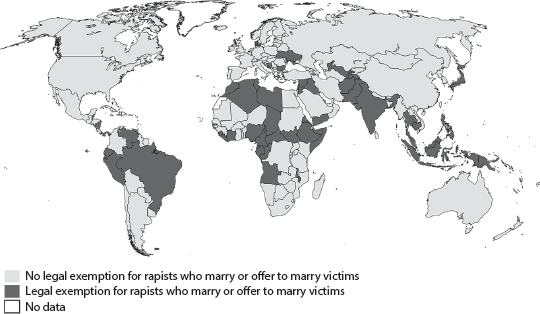

1. prevalence of male willingness to use physical coercion against women, which includes both levels of violence against women, and degree of sanction/impunity for such violence, to wit—

a. overall level of violence against women;

b. societal sanction for the murder of women; and

c. whether a rapist can escape punishment by offering to marry his victim (indicating that female security is but a property right belonging to males);

2. prevalence of patrilocal marriage;

3. prevalence of cousin marriage;

4. preference for sons, including sex ratio abnormalities;

5. age of first marriage for girls in law and practice;

6. overall inequity in family law/practice favoring males;

7. prevalence of brideprice and dowry;

8. prevalence of polygyny in law and practice; and

9. property rights of women in law and practice.

We then developed a scale of how closely a society came to a complete incarnation of the Patrilineal/Fraternal Syndrome using these eleven variables. We first approached construction of this scale through an exploratory factor analysis of the eleven components of the Syndrome, and followed with the creation of a combinatorial algorithm to produce the scale. Appendix I provides a full description of each of the eleven variables used to create the Syndrome score, the results of our exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses justifying the combination of these variables into the Syndrome scale, the algorithm used to combine subcomponent score, and Cronbach’s alpha measuring reliability of the scale, as well as specifies coverage of countries and time periods. The appendix also provides the Syndrome scores for 176 countries (all those with a population of at least two hundred thousand) for the time period from 2010 to 2015. We call this overall index the Patrilineal/Fraternal Syndrome scale. This scale ranges from 0–16, with 16 being interpreted as meaning the society fully encodes the Patrilineal/Fraternal Syndrome as its security provision mechanism, and 0 meaning that the society is free of Syndrome practices.

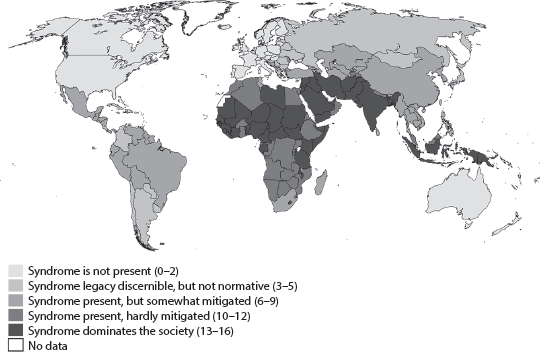

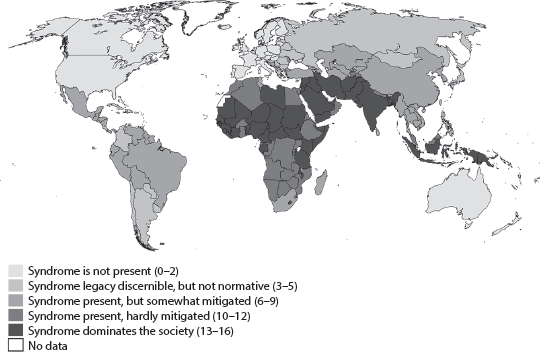

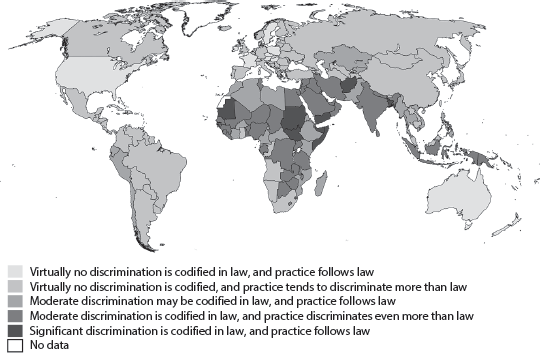

With this scaling in hand, we produced a map (figure 3.1) showing the 176 countries in our analysis. Mapping sixteen colors is not realistic, so for the map’s five legend colors, the cut-points we selected as inductively sound were [0,1,2], [3,4,5], [6,7,8,9], [10,11,12], [13,14,15,16]. For a dichotomous measure (Syndrome/non-Syndrome), then we propose that 0–5 would be considered as, generally speaking, non-Syndrome societies, and 6–16 would be considered, generally speaking, Syndrome societies. Furthermore, we suggest that scores of 6–9 indicate that a society is in clear transition, with either directionality of transition possible. We will utilize this trichotomy [0,1,2,3,4,5], [6,7,8,9], [10,11,12,13,14,15,16] in subsequent chapters as we explore the dynamics of change.

FIGURE 3.1 Map of the Patrilineal/Fraternal Syndrome Scale, scaled 2017

The map clearly shows the full spectrum of degree of reliance on male-bonded kin groups in the world today. Many nations lack the components of the Syndrome almost entirely, and yet in quite a few nations, the Patrilineal/Fraternal Syndrome remains the most dominant security provision mechanism in the society and nearly all components of the Syndrome can be found. Furthermore, even today, quite a few nations in the medium-gray or transitional portion of the map experience legacy effects from earlier, fuller instantiation of the Syndrome.

The complete range of data from 0 to 16 is evident in the scale scores, with South Sudan being the lone country scaled as instantiating the fullest version of the Syndrome in the present time period at a scale point of 16. The histogram in figure 3.2 shows that countries cluster into roughly three categories of severity when it comes to the Syndrome’s enactment: we interpret these three categories as indicating non-Syndrome, Transition, and Syndrome societies.9 In the final chapter, we discuss the dynamics of change and evaluate the case of those middle countries transitioning between the two extremes: Under what conditions do these nations move away from the fuller Syndrome? Under what conditions do these nations regress toward the fuller Syndrome? What are the policy implications of the answers to these questions?

FIGURE 3.2 Histogram of Syndrome Scale scores for 176 countries

If we use a dichotomous approach, with countries scoring 5 and under deemed as no longer encoding the Syndrome, and with countries scoring 6 and above as fundamentally rooted in the Syndrome, then 56 countries are presently scaled as non-Syndrome, and 120 are scaled as Syndrome-based countries. Syndrome-based countries thus outnumber non-Syndrome countries by more than two to one. If we look only at the high-scoring countries, for which almost the full complement of Syndrome variables is evidenced (i.e., scale points 13–16), 40 countries in our sample of 176 nations currently meet that description. The Syndrome is clearly still very much with us even in the twenty-first century.

In terms of geographic distribution, the high-scoring countries are located in a belt across sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, West Asia, and South Asia, extending into Indonesia. Transition countries, or countries in the middle-scoring cluster of nations, show great geographic diversity, with such nations spread across all continents except for the island continent of Australia. Non-Syndrome countries are generally found in that set that might be called the member nations of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Construct Validity Checks

Is the Syndrome scale measuring what we hope it measures? That is, does it possess “construct validity”? To assess construct validity, we examined the correlations between our Patrilineal/Fraternal Syndrome scale and two scales that measure the degree to which clans and tribes dominate society. We also looked at two oft-used measures of the overall situation of women. We would hope to see strong positive correlations, as the Syndrome score gauges both clan governance as well as women’s status. The Syndrome scale, however, measures both of these concepts in different ways from these other scales. The clan scales we examine, for example, emphasize variables other than whether women are controlled in marriage and are insecure; furthermore, the two scales of women’s overall situation in society that we use for the construct validity check do not focus on women’s household-level disempowerment as the Syndrome scale, but focus instead on women’s economic, education, and political participation.

The two scales we selected for this construct validity check are a tribalism scale created by David Jacobson10 and a clan governance scale created by Weiner,11 each of which represent independent approaches.12 The purpose of each scale is to gauge the degree to which extended kin networks dominate the politics of a nation-state. The bivariate correlation (N = 155) between the Syndrome scale and Jacobson’s tribalism scale was 0.487, which was significant at the 0.001 level, and that between the Syndrome scale and Weiner’s clan governance scale (N = 160) was 0.489, which again was significant at the 0.001 level.

We selected two scales of women’s overall situation in society for this construct validity check: the Global Gender Gap Index (GGI, 2016) of the World Economic Forum, and the Gender Inequality Index (GII, 2015) of the UNDP. In the GGI, a higher score is better, whereas in the Syndrome scale, a higher score is worse. Thus, we would expect a strong negative correlation between these two scales and that is what we find: the correlation between the Syndrome scale and the GGI (N = 144) is −0.670, significant at the 0.001 level. The bivariate correlation between the Syndrome scale and the GII (N = 155) was 0.800, significant at the 0.001 level.

All of these correlations are comparatively strong, significant, and in the anticipated direction. We conclude that the Syndrome scale has construct validity as a measure that seeks to capture the degree of reliance on male-bonded kin groups within a society based on a women’s situation in marriage and on their personal status and security, which in turn is reflective of the overall levels of gender inequality within a society. Because we feel the Syndrome, reflecting the first political order, is the wellspring of both of these societal-level phenomena, in a theoretical sense, we feel justified in using the Syndrome to explain the presence of clan governance and the level of gender inequality, rather than the other way around.

Before we can discuss the consequences of the Syndrome for the outcome measures of interest concerning governance, security, stability, and resilience of the nation-state in part II of this volume, we must first set the stage to see those connections by examining how each component of the Syndrome affects the lives of those who experience it, especially the women themselves. As we come to understand those experiences, we will establish the theoretical groundwork on which to put forward a variety of propositions linking the Syndrome variables to the state-level outcomes of national security, stability, and resilience.

The Individual Components of the Syndrome Today

Jacobson rightly notes that “traditional (and especially tribal) patriarchy, the rule of men,…tends to be in the mold of vitriolic hostility to women’s rights.”13 In this section, we detail how each component of the Syndrome affects the lives of women and girls as well as the pertinent effects on men and boys. The picture is unrelievedly tragic. Jacobson may be right when he suggests that it is the treatment of women and girls that represents the deepest “global fissure” in the world today,14 deeper than ethnicity or religion or ideology. As he puts it, “This is the first global struggle over the nature of the self…A critical issue is ‘self possession,’ or who owns and controls one’s body, especially when it comes to women: is it the individual herself or the community[?] Women are now at the heart of the world’s most dangerous quarrel.”15

We argue that the tragic consequences of women’s subordination are not confined to women, but extend to all men, all children, and all nations in which the Syndrome organizes society. In this chapter, we explore the effects of the Syndrome on women and girls, and to a lesser extent men and boys, but in part II, we explore the wider national-level effects, demonstrating that the Syndrome affects virtually all aspects of the nation-state’s situation, including political, economic, and security dimensions.

What follows is an overview of each of the eleven subcomponents of the Patrilineal/Fraternal Syndrome scale, emphasizing how each means of control functions to support the male-bonded kin group, and how each undercuts the position of women and girls.

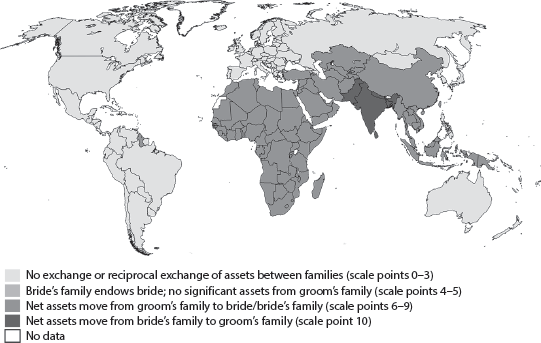

Some people who live in the Western hemisphere might be surprised to learn that the practices of brideprice and dowry are prevalent in the early twenty-first century. The societies that maintain these practices represent almost half of the world’s countries, and account for far more than half the world’s population—indeed, more accurately, almost three-quarters of the world’s population—and span a wide range of regime types, including communist one-party rule in countries such as China.17 Brideprice, or payment from a groom to the bride’s family, is far more common than dowry, or payment from the bride’s family to the groom, in today’s world. David Barash finds that two-thirds of societies in the Ethnographic Atlas practice brideprice, with only a few, largely South Asian societies practicing dowry today.18

Several patterns can be seen in figure 3.3: a regional pattern, an economic pattern, and a cultural pattern. Jack Goody noted in 1974 of the former that “the data shows the dominance of bridewealth in all continents except America.”19 In the modern day, we would include Australia, Europe, and other cultures such as Japan. As for the economic pattern, setting aside the Americas for a moment, we also see that more developed countries do not practice brideprice. As anthropologists Alice Schlegel and Rohn Eloul note, “Absence of marriage transactions, beyond the small gifts that usually accompany the establishment of social bonds everywhere, is itself of interest, as it implies that property, and the reallocation of labor or status, either are not critical issues for those households or are not negotiated through marriage.”20

FIGURE 3.3 Map of Brideprice/Dowry/Wedding Costs, scaled 2016

Finally, with regard to ethno-religious patterns, predominantly Christian cultures appear less likely to practice brideprice in the contemporary era. There are reports of Christian missionaries inveighing against the practice during the colonial period, likening it to slavery.21 The case of sub-Saharan Africa deserves special mention: although sub-Saharan Africa has a strong Christian presence, Christians account for only about 38 percent of the population, and Christian families often find it difficult to part ways with the larger culture on this practice.22 In this area, therefore, one can find substantial representation of Christians in countries where brideprice is prevalent. Although this and other regional, economic, and cultural exceptions exist, brideprice is a dominant practice in much of the world. Indeed, those living in countries without this practice may underestimate the prevalence and importance of this custom.

Our own scaling of brideprice/dowry finds a roughly equal bimodal distribution, shown in the histogram in figure 3.4, among the nations of the world. As noted earlier, however, about three-quarters of the world’s population lives in countries that still practice brideprice/dowry.23 Although there are profound consequences of brideprice/dowry for societal stability, which will be explored in the next chapter, we confine this discussion to an examination of the effects of this practice on women.

FIGURE 3.4 Histogram of Brideprice/Dowry/Wedding Costs Scale

(Note: 0 indicates no brideprice, dowry, or obligatory wedding costs)

The natural consequences that grow out of this system are deeply detrimental to the status of women, despite the fact that the practice is often justified as a protection to women in case they are divorced by their husbands. In addition to patrilocal marriage and lack of property rights, brideprice/dowry societies are characterized by arranged marriage in the patriline’s interest, relatively low age of marriage for girls, profound underinvestment in female human capital, intense son preference, highly inequitable family and personal status law favoring men, and chronically high levels of violence against women as a means to enforce the imposition of the patrilineal system on often recalcitrant women. Consider the findings of a Tanzanian women’s organization following an extensive survey that “due to brideprice,” women suffer “insults, sexual abuse, battery, denial of their rights to own property, being overworked and having to bear a large number of children.”24 One female assembly member in Ghana noted that “some of the young men who were able to afford the items [in the brideprice] treated their wives as ‘slaves’ or ‘properties’ they had acquired with their wealth because of the huge sums they spent.”25 Psychiatric researcher Susan Rees and her colleagues, studying brideprice in Timor-Leste, find strong associations to intimate partner violence (IPV) against women, women’s anger and mental distress, and a deep feeling of injustice among women whose marriages involved the payment of brideprice.26

An IRIN report relays that “Women also complained of some men’s tendency to reclaim the brideprice when marriages broke up, saying fear of this outcome forced women to cling to their marriages even when abused.”27 An article from a Ghanaian newspaper concurs: “Women who wanted to divorce their husbands because of ill treatment were made to return the exact dowry collected before the marriage, and since most families are not able to refund the items, the women are left to suffer in the marriage.”28

Journalist Marc Ellison tells the story of Grace in rural Tanzania, who refused to marry an older man, and then was abducted at age twelve and forcibly married to him so that her father could obtain the negotiated brideprice. The human toll for these girls is catastrophic: Grace was beaten and raped every day for eleven months until her husband died in a motor accident, leaving her penniless and with a baby. In Grace’s case, the brideprice was in cows, and she comments, “Bitterness still fills my heart when I look at them [the cows]; Given what I went through, I wish I had been born a cow. That day felt like the end of everything.”29 Ellison notes that in Grace’s region of Tanzania, almost 60 percent of girls are married as children, and it gives pain to note that the motto of the men in her ethnic group is “alcohol, meat, and vagina,” naming the three things to which every man is entitled. Of course, that “vagina” is attached to a real, living human being.

As noted in chapter 2, two variants of the Syndrome also demand our attention, particularly given their effects on the status of women overall. First, where women’s work is valued in the productive labor of the society, such as farm labor, brideprice and polygyny are often prevalent. Given that marriage is patrilocal and inheritance effected through the patriline, buying or exchanging women between descent groups becomes essential, and brideprice becomes the reimbursement to the family who invested the resources necessary to raise the girl to puberty. Richer men within the kin group can afford to pay the brideprice for more than one wife, and thus they ensure for themselves even greater returns on investment than those who cannot. As Schlegel and Eloul note, in such societies “the powerful man does not keep his wealth, but distributes it to acquire wives and in-laws.”30 This brideprice-with-polygyny-for-the-rich system is by far the most prevalent variant of patrilineality. Goody finds that 78 percent of the patrilineal cultures he has studied practice brideprice, and a further 6 percent practice bride-service, a variant thereof.31

The second, less frequent variant of dowry occurs in cases in which women are not valued for their productive labor; women are seen as a burden, and those who give the bride must be prepared to compensate the groom and his family for their assumption of this burden through payment of a dowry. Goody explains, “Bridewealth is more commonly found where women make the major contribution to agriculture, whereas dowry is restricted to those societies where males contribute most; this is the difference between hoe agriculture and the use of the plough, which is almost invariably in male hands.”32 Furthermore, one can also find societies in which dowry is practiced in higher socioeconomic classes, but brideprice is practiced among the poor. In such societies (and India is one), dowry among the rich becomes, in anthropologist John McCreery’s words, “a means of social mobility in stratified societies where men use rights over women, like other property, to compete for higher status.”33 In contrast, among the poor, especially in cases in which dowry has caused sex ratio alteration, the poor must pay for a bride.

The practice of brideprice differs from that of dowry in its effects on the status of women; tellingly, dowry is more often associated with female infanticide and sex-selective abortion, for families can be bankrupted by daughters whose dowries they must pay. The negative consequences of dowry on the lives of women are well-known. Demographer P. N. Mari Bhat and public health expert Shiva Halli write that in India, the “amount of dowry demanded has grown to a size that threatens the destitution of households with many daughters,”34 with up to two-thirds of total household assets going toward one daughter’s dowry in some places. Furthermore, they note that “while a large dowry does raise the prestige of the bride among her affines, more importantly, a small one can make her life miserable in the new home. The number of instances of such harassment that lead to either the suicide or murder of the helpless woman is increasing rapidly, and these cases frequently make newspaper headlines.”35

The effects of brideprice, in contrast to that of dowry, are less well recognized. In patrilineal systems, obligatory brideprice becomes a tax on young men, payable to older men. The young man’s father and male kindred may help him pay that tax, but the intergenerational nature of the tax should not be overlooked, especially in the case of poor young men whose father and kin may not be of much assistance for any number of reasons. Brideprice can be costly: in a recent article, the regional brideprices in Afghanistan ranged from a low of 100,000 afghanis to a high of 3 million afghanis (between $1,450 and $45,000). Furthermore, even though such a brideprice may be considered a mahr or dower that is supposed to be the property of the bride, this almost never occurs. This is a brideprice that almost always goes to the girl’s father or brother. As one man from Ghazni said,

On the day of my engagement in 2011, my father and brothers decided on a sum of 800,000 Pakistani rupees [about US$9,230] to be given as mahr to my future wife. The money was paid directly to her brother and after the wedding, when I asked my wife about the mahr, she told me that she did not receive a penny of the 800,000 [Pakistani] rupees. Instead, she told me that her brother had used the money to arrange the marriage of his son.36

Marriage is often delayed for men as they often must migrate to earn these sums, and marriage is often quite early for women as male relatives want the brideprice to pay for their own wedding costs, which means the age gap between spouses can be quite large.

The impact of wedding costs, even apart from brideprice or dowry, must also not be overlooked. In a recent New York Times article, Joseph Goldstein tells the tale of a thirty-one-year-old groom in Afghanistan who was a car salesman. On top of the brideprice, he was also expected to pay for a wedding that would feed well over six hundred people—most of whom he did not even know. The cost of his wedding was $30,000, and he would have to take out loans that would take him years to repay. When Afghanistan was considering a cap on the number of wedding guests at five hundred people (which bill passed in 2015), one young man expressed to Goldstein, “I demand that the president sign this law,” said Jawed (twenty-four years old), who sells fabric in a small stall in an underground shopping mall. “I beg him to sign this law as soon as possible so people like me can get married soon.”37

Brideprice has caused problems throughout Afghanistan’s history. Valentine Moghadam notes,

way back in 1978, the new left-wing government in what was then the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan decreed a limit to brideprice (walwar). This was one of the reasons for the tribal-Islamist uprising that began in the summer of 1978 (another was compulsory schooling, especially for girls). Stupidly and tragically, the DRA reforms were denigrated as “Sovietization” by outside detractors, including those in Human Rights Watch (like Jere Laber).38

The problem is so serious that several state governments have gotten involved in limiting these egregious wedding costs. For example, Tajikistan recently passed a law that allows the government to seize excess wedding items, such as food, and imposes a $4,000 fine for offenders. Tajik officials may be fired if they are found holding outsize weddings.39 The Saudi government has also been proactive, as well, in attempting to limit wedding costs.40

Why marry at all, then, if the brideprice is exorbitant? The logic of patrilineality demands marriage. As Farea Al-Muslimi comments about Yemen, “as soon as a young person reaches puberty, their only concern becomes marriage.”41 A man’s place in the agnatic lineage is only assured if he maintains that patriline into the future. Without a son, there is no one to inherit his position and his wealth, which will then devolve to his brothers and cousins. Without a son, there will be no one to take care of him in old age or to perform requisite religious rituals for his soul. If a man breaks the patrilineal chain, he cannot be regarded as an honorable part of the lineage group. For example, Monica Das Gupta notes about Korea,

[Ancestors] who died unmarried or without male descendants are filled with resentment and can create all kinds of problems for their siblings and other kin. It is apparent that there is much pressure from a wide range of family members to ensure that each individual performs their filial duties of marrying and bearing sons quickly, and caring for their ancestors.42

Therefore, even if brideprice or dowry is high, young men will strive mightily to marry and produce sons. Important in understanding the consequences of brideprice is the evidence that brideprice acts as a flat tax—for the most part, brideprice is the same “going rate” within the society. The brideprice is nudged slightly upward or downward at the margin according to the status of the bride’s kin, but it is not affected greatly by the status of the man responsible for paying it. If the cost of brideprice rises, it will rise for every man, rich or poor. The flat-tax nature of brideprice is independent of geographic region; studies conducted in Afghanistan, China, and Kenya found that regardless of socioeconomic class, young men are expected to pay the same price to get married.

The tendency toward a consistent brideprice is easily understood. Goody suggests, “in bridewealth systems, standard payments are more common; their role in a societal exchange puts pressure towards similarity.”43 The reason for this is that men pay for their sons’ brideprices by collecting the brideprice for their daughters. This is another force pushing down girls’ age of marriage. In a given family, unless it is very wealthy, daughters in general must be married off first so that the family can accumulate enough assets to pay the sons’ brideprices. Quoting anthropologist Lucy Mair, Goody remarks, “ ‘when cattle payments are made, the marriage of girls tends to be early for the same reason that that of men is late—that a girl’s marriage increases her father’s herd while that of a young man diminishes it’…Men chafe at the delay, girls at the speed.”44 If brideprice were variable within a society, families could not count on the brideprices brought in by their daughters to be sufficient to fulfill the obligation they owe their sons. Thus, over time, a fairly consistent brideprice emerges for the community at any given time, although the actual cost may trend upward or downward over time depending on local conditions.

Indeed, many accounts suggest that men are sensitive to any new trends in brideprice, and the societal brideprice level is easily pushed upward. Quoting Mair again, Goody notes “Every father fears being left in the lurch by finding that the bridewealth which he has accepted for his daughter will not suffice to get him a daughter-in-law; therefore he is always on the lookout for any signs of a rise in the rate, and tends to raise his demands whenever he hears of other fathers doing so. This mean in general terms, that individual cases of over-payment produce a general rise in the rate all around.”45 This is true even in the case in which governments try to cap brideprices to stop this inexorable inflation; for example in Niger, even though the government has placed a cap of 50,000 CFA francs on brideprices, in practice families pay far more than this amount.46 (The attempt to cap brideprice can be a catalyst for rebellion, as we saw in the case of the attempted reforms in the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan in the 1970s, which was a catalyst for insurgency.) Poorer men who must delay marriage to save up enough to marry may find that brideprices have also risen over time, making their endeavors to “catch up” impossible in the end; this phenomenon also has been noted in China.47

Exigency plays a role in the sudden rises and sudden falls of brideprice. Brideprice can collapse precipitously in times of exigency—for example, Yemen’s civil war has caused just such a collapse. Before the civil war, a brideprice of 1 million Yemeni rials was standard (about $4,650). After the war was underway, the going price dropped to about 300,000 Yemeni rials. Although some families never considered marrying their daughters for such a low price, and refused to have them married as a result, other families were concerned whether their daughters would be able to marry at all and took the lower price.48 When they took the lower price, they lowered the price for all, causing on overall collapse in price. Steep inflation in brideprice can also occur as a result of exigency, for example, from abnormal sex ratios. The Economist reports that brideprice in rural China has increased dramatically over the past decade, from about 3,000 yuan to more than 300,000 yuan as a result of the increasing scarcity of brides.49

As noted, brideprice is associated with early age of marriage for girls, because that practice ensures that men may accumulate capital to purchase wives. Women’s economic value as wives, when added to their value as marriageable daughters, allows for the accumulation of wealth to bring in more wives. As a result, the sale of daughters tends to take place as early as practicable, pushing down the age of marriage for girls. As Goody remarks, “Polygyny…is made possible by the differential marriage age, early for girls, later for men. Bridewealth and polygyny play into each other’s hands…the two institutions appear to reinforce each other.”50 We have already noted that this polygynous tendency will be exaggerated in societies in which women perform a substantial proportion of productive labor, such as farm labor. Buying additional wives is thus one route to increased wealth through accumulating a larger labor force. Polygyny is also a marker of higher status within the society, and is sought after for display of that higher status, as well, even in societies in which women’s labor is not valuable (such as in the United Arab Emirates).

Given the social utility and centrality of marriage in these patrilineal contexts, brideprice is not a luxury tax affecting the budgets of the elite, but rather it is more akin to a regressive tax that disproportionately affects the poor and middle class. This places a heavy economic burden on young men—particularly in situations of economic stagnation, rising inequality, or brideprice inflation. A summary of the average brideprice from a number of different periods and countries found that the burden equated to as much as twelve to twenty times the per capita holdings of large livestock or two to four times gross household income.51 We will explore the societal effects of such a strain in chapter 5 of this volume.

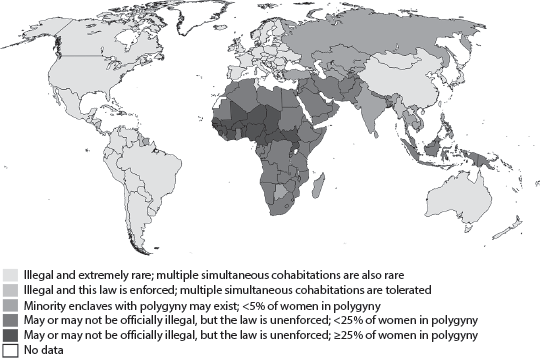

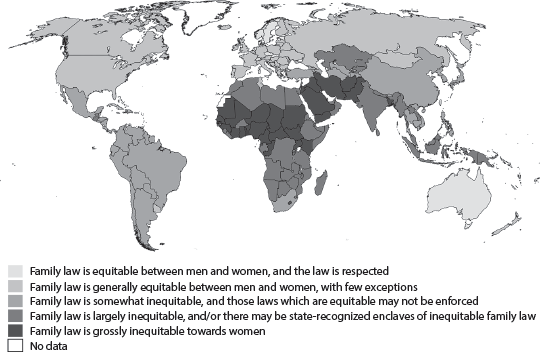

Polygyny

Polygyny, that is having formal or recognized marriages with two or more women, is not uncommon in today’s world (figure 3.5). Indeed, Rose McDermott and Jonathan Cowden suggest that it exists “in more than 83 percent of 849 cultures worldwide,” and note that “everywhere the practice is more widespread among high-status, high-wealth men.”52 Polyandry, virtually never practiced in human societies, is a practice of the very poor and is usually fraternal, that is, where brothers share a wife because they are too poor to afford the brideprices required for each one to marry separately. It is telling that even in cultures with traces of polyandry, rich men will still take multiple wives.

FIGURE 3.5 Map of the Prevalence and Legal Status of Polygyny, scaled 2016

Although most prevalent in Sub-Saharan Africa and Islamic-majority countries, polygyny in some areas is creeping back in after decades of suppression, such as in post-Soviet Central Asia or in areas with high numbers of widows because of warfare.53 Polygyny is easily effected by wealthy elites in brideprice societies. As Goody notes, “Bridewealth [i.e., brideprice] and dowry have different potentialities in the way they can link up with the politico-economic institutions of the society where they are found. Bridewealth can neatly tie in with polygyny.”54

Polygyny serves two distinct functions. It is most widely known today as a marker of elite status, as only the wealthy will be able to afford to pay multiple brideprices. Polygyny also cements more than one political alliance among the various leaders of male kin groups. Such marriage alliances are more durable and more likely to deter internecine conflict than those not sealed by marriage and offspring.55 Anthropologist Thomas Barfield notes, “marriage ties created patterns of alliances that crosscut the seemingly rigid set of patrilineal relationships within a conical clan. For this reason, polygynous marriages by tribal rulers were common.”56

Status is also displayed in the formation of these alliances; for example, social anthropologists Madawi Al-Rasheed and Loulouwa Al-Rasheed observe that when the house of Saud won out over the Rashidis, they smoothed relations by marrying Rashidi women in polygynous circumstances, but they never allowed Saudi women to marry Rashidi men, for “wife-givers” are in status inferior to “wife-takers.”57 As a status marker, polygyny is an effective means of raising one’s status even when one’s birth status is not extraordinary. As Goody notes, brideprice has “a leveling function,”58 by which he means that as long as a man has the requisite assets, in many cases he can marry a comparatively high-status woman regardless of his own family’s social standing.

This type of elite polygynous marriage as a status marker can occur in various types of economic systems. Polygyny, however, takes on a special cast in societies in which agriculture is the primary source of wealth and in which women are the primary agricultural laborers. In such societies, polygyny arises as an effective means of improving the rate and the absolute amount of wealth accumulation for a subset of men. Goody notes, “Polygyny is found where women make a substantial contribution to productive activity, especially to cultivation.”59 Marrying more women increases the amount of land that can be profitably cultivated, and surplus income can even be used to marry additional wives.

The effects of polygyny on women and their children are as profound as those of brideprice and dowry. Unless the family is so wealthy that resources are bounteous, polygyny significantly depresses investment in women and children beyond the initial investment in the acquisition of the wives involved. Numerous studies have demonstrated that significantly less attention is paid to the health (physical and mental), nutrition, and education of women and children in polygynous households.60 Richard Alexander notes that a man may trade off investment in his offspring for the ability to purchase additional wives as a reproductive strategy.61

McDermott and Cowden find a statistically significant relationship between the legality and prevalence of polygyny within a country, on the one hand, and what they call “an entire downstream suite of negative consequences for men, women, children, and the nation-state,” on the other.62 Their data analysis points to a significant relationship between polygyny and unequal family law, higher birth rates, rates of primary and secondary education for both male and female children, HIV infection, low age of marriage for girls, high maternal mortality, lower life expectancy, higher levels of sex trafficking, and higher levels of domestic violence. The evolutionary psychologist Satoshi Kanazawa has also found lower age of menarche.63 Other experts have pointed to psychological harms for women and children in polygynous marriages, including anxiety and depression.64 This anxiety and depression may not only be felt by women (and their children) already in polygynous relationships but also by women (and their children) currently in monogamous relationships, who must worry about whether their husband and father will take additional wives. In a cross-cultural sample, Barash finds that 90 percent of polygynously married women reported sexual and emotional conflict, particularly involving children and the allocation of resources within the household.65

McDermott and Cowden also note that polygyny often creates a class of unmarriageable young men. In the polygynist communities in the western United States and Canada among the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS), a group splintered off from the Mormon Church that still practices polygyny, they are called the “Lost Boys,” for they are thrust out of their communities.66 For wealthy men to have many wives, a sizeable number of young men must have none. As we detail in chapter 5, this may catalyze instability and even conflict. In addition to the substantial risk of being crowded out of the marriage market, Barash notes that sons in polygynous cultures are affected in other ways, as well. For example, sons often are socialized to be highly competitive and aggressive in polygynous cultures.67

Polygyny reliably produces harms for children. We have noted McDermott and Cowden’s findings on lower rates of primary and secondary education for girls and boys, but the literature finds consistent underinvestment overall in the children of polygynous unions. The evolutionary biologist Joseph Henrich asserts that “polygynous men invest less in their offspring both because they have more offspring and because they continue to invest in seeking additional wives. This implies that, on average, children in a more polygynous society will receive less parental investment.”68 Henrich and his coauthors cite several studies showing that in both West Africa and East Africa, children in polygynous households had significantly higher death rates and significantly poorer nutrition than children in monogamous households.69 For example, among the polygynous Dogon tribe of Mali, a child born to a polygynous family is seven to eleven times more likely to die early than one born to a monogamous couple; among the Temne of Sierra Leone, the mortality rate among children born into polygyny was found to be 41 percent, compared with 25 percent for those born into monogamy.70 Fascinatingly, they also note that the survival rates among nineteenth-century Mormon children in Utah were actually lower for wealthier families that practiced polygyny than for poor families that did not. Even among the modern FLDS, rampant child labor, malnourishment, physical abuse, and inbreeding all take a tremendous physical and emotional toll.71 Because of all of these demonstrable harms, Canada has upheld the constitutionality of a ban on polygamy in both 2011 and 2018.72 We outline additional consequences of polygyny in chapters 4 and 5 as we trace the effects of the Syndrome’s components on the larger social order.

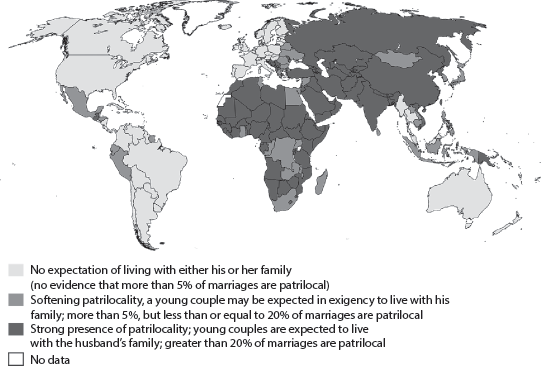

Patrilocality is a natural extension of the logic of patrilineality as a system of security provision (figure 3.6). Male blood relatives stay together to provide the requisite fraternal alliance, and it is women who must move to bring about the needed exogamy that will prevent genetic disaster. Women move out of their natal home and go to live with their husband’s kin group. In some cases, they may never see their birth family again.73 Economist Louise Grogan estimates that at least 70 percent of human societies practice patrilocal marriage.74

FIGURE 3.6 Map of the Prevalence of Patrilocal Marriage, scaled 2016

Avraham Ebenstein argues that the logic of patrilocality reaches its zenith when the chief inheritable asset is land. He asserts:

The adoption of patrilocal norms serves to keep the son close for defense, to provide him wealth to support one or more wives, and to care for his elderly parents in their old age…and sons need their fathers’ land. Often, this implicit barter will be further reinforced by religious norms that develop to enforce the agreement, such as Confucianism’s focus on filial piety, or the need for a son to pray for the dead in Hinduism…. The elders become the holders of capital, and can exchange this for their children’s labor, mediated through a norm of coresidence.75

Although inheritable land drives patrilocal norms in some cultures, it is also true that nomadic tribes often practice patrilocality as well, and for many of the same reasons, such as defense by the extended male kin group. We suggest it is necessary to examine the prevalence of brideprice in connection with patrilocality, for the need to produce brideprice also fuels the need to consolidate (as versus disperse) patriline assets, and again this favors patrilocal norms.

As with brideprice or dowry and polygyny, the effects of patrilocal marriage on women are detrimental. Patrilocality typically cuts off a woman from sources of kin support that may serve to protect and sustain her. In fact, her birth family may come to see investment in her as a daughter as meaningless, for she will soon depart from their midst to join her husband’s family.76 We find proverbs from all over the patrilocal world that demonstrate this attitude: “Raising a daughter is like watering a plant in another man’s garden,” “A daughter is a thief,” “A daughter is but a houseguest.” This may help explain other norms, such as differential feeding practices for daughters and sons, and differential investment in health and education.

Once this “outsider” reaches her new home with her husband’s family, she is likely to face more differential treatment—as well as suspicion and perhaps even abuse. This predisposition actually may be augmented by the payment of brideprice, which may be taken by some to mean that the girl has been bought, and thus she has the status of a chattel. As Xie Lihua of Rural Women’s Magazine in China put it, “there’s a saying among men: ‘marrying a woman is like buying a horse: I can ride you and beat you whenever I like.’ Men feel that ‘I’ve spent money on bringing you into my family, so I have the right to order you around.’ And a man will beat a woman if she has a mind of her own.”77

In addition to physical consequences, there are also profound psychological consequences for the woman. Where, exactly, is her home, that is, her place of safety and acceptance? It appears not to be either in her parents’ home or in her in-laws’ home. What is her central love relationship? It is not to be found in her birth family, and it is not with her husband. Rather, her only lasting love relationship is with her son, if she produces one, which accounts for the deep tension between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law when that son marries. It also accounts for intensified son preference; as Grogan notes, “Sons are the key intergenerational link where women move to their husband’s natal residence upon marriage.”78

Furthermore, the patrilocal nature of marriage puts the woman at risk should she be widowed or divorced. A widow may be subject to levirate marriage (marriage to her dead husband’s brother or other near kin), or she simply may be ousted from the household by her in-laws and left to forage for herself. She may not be able to inherit as a widow from her husband in some cultures, with all his property reverting to the patriline. A woman who is divorced may also lose custody of her children, because they are considered to be affines of her husband’s family, and she may not be able to return to her birth family, either, leaving her without a place to live.

Although urbanization attenuates patrilocality, the practice can return after decades of more neolocal marriage norms. For example, Grogan notes that after the fall of the Soviet Union, economic shocks and rising instability catalyzed a return to a patrilocal marriage norm in nations such as Tajikistan.79 Again, we see that reversion to the security provision mechanism of the Patrilineal/Fraternal Syndrome as the result of exigency will also cause a regress in the situation of women at the household level.

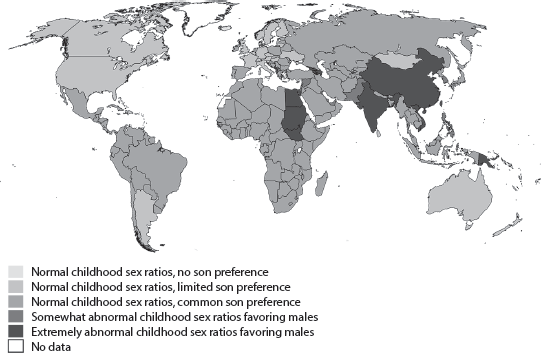

Son Preference and Sex Ratios

A discussion of son preference and sex ratios naturally follows from a discussion of brideprice, polygyny, and patrilocality (figure 3.7). Son preference follows from patrilineality as one more logical extension. From all that we have learned, it is clear that the “true members” of a kin group are the males in the patriline, and for a man to continue that kin line is obligatory for him to have full standing in the group and to be able to pass an inheritance to his own posterity and not to his brothers. That means he must have a son; a daughter will simply not suffice. Although daughters may be valued for their instrumental usefulness in bringing in a brideprice, or for their productive or reproductive labor, only sons have existential value and thus merit sustained investment in their nutrition, health care, and education. Only sons are a bridge to the future for a patriline; only sons bring to their fathers a permanent standing in the lineage group.

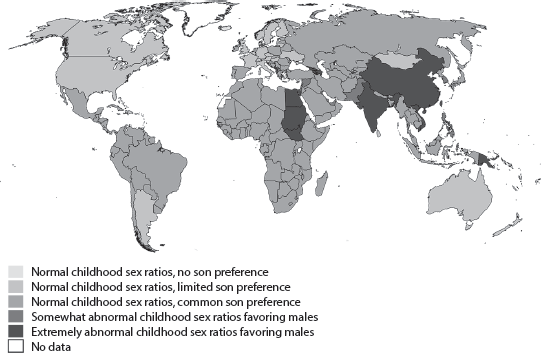

FIGURE 3.7 Map of Son Preference and Childhood Sex Ratios, scaled 2015

Intense son preference can lead to high fertility and high maternal mortality rates in some societies. One Afghan woman was interviewed by the Afghan Women’s Writing Project in the Herat Maternity Clinic, and offered her story:

First I talk to a woman who tells me about her life with tears pouring from her eyes. Wounds on her face show she has recently been beaten. She cannot tell me much, she is afraid and cannot say her name to me, but she talks about her life. She does not tell her age; she says only that she was the youngest in her family. She is pregnant with her ninth child. She has eight children who are all girls, and in three months her next child will be born. She says her husband’s family forced her to continue to become pregnant to give birth to a boy and she says this time she knows she will have a son because the pregnancy feels different from the other times. All of her children were born at home and she came to the clinic only because of bleeding. Her husband had beaten her. She says if she does not bear a son her husband will end their marriage and will abandon her with her daughters.80

Part of the calculus of son preference is that because of patrilocality, only sons provide old age insurance for elderly parents. Daughters will be leaving to live with their husband’s family, but sons will stay and are responsible for the care of elderly parents. As Das Gupta notes, “Son preference is found in certain types of cultures, that is, patrilineal cultures…[where] daughters are formally transferred on marriage to their husband’s family and can no longer contribute to their natal family. This drastically lowers the value of daughters relative to sons, reducing parents’ willingness to invest in raising girls.”81

Thus, we are not surprised to find that patrilocal norms are strongly associated with abnormally high sex ratios favoring males.82 That is, these norms incentivize both the bearing of sons and the prevention of the birth of daughters either through female infanticide or sex-selective abortion. Ebenstein notes this connection, stating

parents abort girls because of patrilocality: [patrilocality] is the single common factor across countries with high sex ratios, and as such, should be viewed as the primary factor in explaining the phenomenon. Patrilocality is the single feature common to the social norms of Christians in Armenia, Muslims in Azerbaijan, Hindus in India and Buddhists in China—all live with their sons when they are old…every country with abnormally high sex ratios at birth in the samples has a high proportion of elderly living with sons.83

Ebenstein shows empirically that even when controlling for measures of gender equity, such as education and employment rates, groups where sons live with their parents have higher sex ratios. His analysis is revealing; he finds that even where women are not otherwise disadvantaged in education or employment, such as in Armenia or China, if the elderly typically coreside with sons, high sex ratios are manifest.84

Armenia is a telling case in Ebenstein’s view, because sex ratios in that country were absolutely normal until the collapse of the Soviet Union. Ebenstein notes that after that event, “Parents realized that old age support would be provided by the family rather than the state.”85 He found that, consequently, sex ratios rose to 53.1 percent male among lower-income Armenians. He posits that this socioeconomic class began to demonstrate son preference to ensure care later in life because they could rely on neither their savings nor the state to provide it. “The Armenian experience documents the dangers facing policymakers when social protections are removed among parents who have access to sex selection technology,” he explains.86

Armenia is not the only post–Soviet era nation seeing a resurgence in male-skewed sex ratios. Azerbaijan, Georgia, Montenegro, and Albania all have seen increased sex ratios, with Georgia clocking in at an estimated 122 boys per 100 girls born in the 2000–2005 period.87 The birth sex ratio in Armenia hit 114.4 in 2011, and Azerbaijan’s was 115.5.88 Furthermore, political scientist Andrea Den Boer also notes excess female mortality in the first few years of life, as well, indicating passive infanticide of girls. (Ironically, the chronic housing shortage in the Soviet Union contributed to the continued cultural practice of patrilocality in this region, according to Den Boer.)

Patrilineal societies typically fuse religious belief with the importance of the patriline, and therefore it is not unexpected to find religious or quasi-religious beliefs supporting son preference. For example, in China, Das Gupta notes,

It is believed that one’s own soul and that of one’s male ancestors need to be cared for by male progeny, without which the dead will become what in China is called “hungry ghosts.” No pension plan can cover care in the afterlife. Angering the ancestors through unfilial acts can bring their wrath down on you in this life, bringing supernatural sanctions and bad luck. Not bearing a son is a major dereliction of filial duty.89

Sex ratio alteration is a telling indicator of women’s disempowerment at the household level. Economist Andrew Francis notes that “the incidence of selective abortion, infanticide, and neglect [of females] is inversely related to women’s intra-household bargaining power. Empowering women, wives and mothers, reduces the number of ‘missing’ women.”90 Indeed, the fact that it is often mothers-in-law who most directly pressure daughters-in-law to get rid of female offspring is a testament to just how disempowered women are, indicating that only the birth of sons lifts a woman’s status in the home, even among other women.

The toll on women’s health of son preference can be appalling; public health expert Narjis Rizvi and colleagues conducted thirty focus groups of 250 women in Pakistan, finding that many of the women indicated that they “continue bearing children until the family has at least one son; she sometimes delivers 7 or more daughters in order to accomplish the objective…. Except the post-delivery period in case of the male baby, when higher allowances are given so that the boy can be breastfed, generally meager nutritional allocation and repeated pregnancies make them malnourished.”91

Interestingly, unless other Syndrome components are present to prevent it, masculinized sex ratios can actually increase women’s bargaining power within the home. That is, in a context in which potential wives are relatively scarce, if women are relatively free to choose whether to marry and have access to divorce, custody, and property rights in marriage, empirical research suggests that, once married, they are able to bargain for greater investment in the children of the marriage (e.g., greater number of years of schooling) as well as ensure lower rates of infanticide, sex-selective abortion and neglect of daughters, and achieve lower total fertility.92 For example, in China, one young man interviewed by the China Youth Daily noted, “In my hometown, the status of the wife and her mother-in-law has reversed, especially in a family with bad finances. The mother-in-law needs to treat the wife carefully in order to avoid the wife leaving the family. It’s not the wife that the mother-in-law truly cares about, it’s [the brideprice].”93 In most Syndrome-encoded societies, however, this situation rarely occurs. Indeed, one could propose that the interlocking straitjacket of the Syndrome purposefully serves, among many other things, to effectively insulate men and their patriline from any such development.

Abnormal sex ratios play havoc with brideprice, as we discussed earlier. As one Chinese matchmaker put it, “The scarcity of marriageable women makes men like a starving man—all food is delicious to them.”94 As brideprice rises beyond the reach of many men, they may seek divorced women or women with mental or physical disabilities, for the brideprice will be considerably lower for these women. Families with several sons may be able to fund only the marriage of the eldest. One family in Hubei, China, with four sons, decided that the four brothers would have to jointly raise enough money for the eldest to marry and that the rest would probably have to forgo any hope of marrying at all.95

Abnormal sex ratios are not a thing of the past; indeed, they are spreading. In 1990, five nation-states had abnormal sex ratios in early childhood (ages birth to four years old); now there are nineteen (twenty-one, if you include Hong Kong and Macau). In 1990, the phenomenon was confined to Asia, but now the countries with abnormal sex ratios across ages birth to four years old include many outside that continent, including Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, China, Hong Kong, Macau, Egypt, Fiji, Georgia, India, Kosovo, Kuwait, Lebanon, Montenegro, Philippines, South Sudan, Sudan, Taiwan, Macedonia, Vanuatu, and Vietnam.96 Expatriate communities may also create enclaves of higher sex ratios; for example, in Canada, Indian-born women with two daughters have a birth sex ratio for their third child of 196 boys per 100 girls.97

Migration can create age-cohort pockets of abnormal sex ratios,98 as has been noted in Sweden after the mass migration of 2015, subsequent to which the sex ratio of sixteen- and seventeen-year-olds in Sweden rose to 123 males per 100 females, far surpassing the sex ratio of China for the same age cohort (117:100). Furthermore, historical path dependencies may be at work—for example, researchers have tied modern West African polygyny to a legacy of abnormal sex ratios resulting from slavery, where about two-thirds of those exported as slaves from West Africa were male.99

The devaluation of female life, expressed most starkly in female infanticide and sex-selective abortion, is interwoven with the history of female subordination stretching back millennia. As Gerda Lerner notes, “One of the first powers men institutionalized under patriarchy was the power of the male head of the family to decide which infants should live and which infants should die. This power must have been perceived as a victory of law over nature, for it went directly against nature and previous human experience.”100 Indeed, as the current estimate of the number of missing women in Asia alone rises inexorably toward two hundred million,101 it is astonishing that the world considers this toll, which dwarfs that of any war, so unremarkable—and so unrelated to national and international security. In part II, we explain how wrong that mind-set proves to be.

Low Age of First Marriage for Girls

Estimates are that almost five million girls are married annually at younger than sixteen years of age (figure 3.8).102 These young girls are, for the most part, not marrying men of the same age: the average difference in age is six years, with the husband being substantially older. In Niger, for example, 59 percent of child brides married a man at least ten years older; the corresponding figure for Bolivia was 46 percent. The United Nations Population Fund notes that 19 percent of young women in developing countries become pregnant before the age of eighteen, and 95 percent of those births occur within marriage. Furthermore, 2 million of the 7.3 million births every year to adolescents are to those who are younger than age fifteen—in some countries, that represents 10 percent of under-fifteen girls.103

FIGURE 3.8 Map of Age of Marriage for Girls in Law and Practice, scaled 2015

Patrilineality tends to be associated with a low age of marriage for girls, even child marriage. This is largely because daughters hold less value compared with sons in patrilineal culture; daughters marry exogamously and therefore are not considered full members of the kin group, but they must be fed, clothed, and housed before marriage; preserving the sexual purity of daughters becomes more onerous to the family with each year past puberty; and daughters may bring in a good-size brideprice upon marriage, which subsequently could be used to contract marriages for the men of the family. Child marriage for girls minimizes expenditures and expedites income that may be needed to pay for the marriages of the more important sons. In addition, child marriage for girls may reduce threats to the family’s honor (and hoped-for brideprice) by reducing the time period in which she is vulnerable to sexual predation.

Exigencies also increase the rate of child marriage for girls. Whether as a result of natural disaster or conflict, crisis will push down the age of marriage as families are scrambling for resources and are willing to marry off girls in exchange. In addition, in desperate situations caused by having to flee conflicts, families may feel completely unable to protect their girls from sexual predation, and marriage may seem the best way to preserve their honor. This dynamic is playing out as we speak among refugees from the Syrian conflict. Save the Children reports,

Child marriage existed in Syria before the crisis—13 percent of girls under 18 in Syria were married in 2011. But now, three years into the conflict, official statistics show that among Syrian refugee communities in Jordan…child marriage has increased alarmingly, and in some cases has doubled. In Jordan, the proportion of registered marriages among the Syrian refugee community where the bride was under 18 rose from 12 percent in 2011 (roughly the same as the figure in pre-war Syria) to 18 percent in 2012, and as high as 25 percent by 2013. The number of Syrian boys registered as married in 2011 and 2012 in Jordan is far lower, suggesting that girls are, as a matter of course, being married off to older males.104

The same phenomenon is observable in Yemen’s civil war, as well, and Oxfam has asserted that girls as young as three years of age are being married off to obtain brideprice to feed the rest of the family.105

Interestingly, a new exigency for modern parents is that educated girls may refuse to marry a partner they deem unacceptable, or they may refuse to marry at all. Marrying daughters off early may prevent such insubordination from occurring. Louisa Chiang notes, “Reversing a long-running trend, some rural families now marry off their daughters earlier, enticed by the high brideprice and concerned that older, more educated daughters are likely to leave or are harder to dictate marriage terms to.”106 The highly masculinized sex ratio pushes down the age of marriage for women, as witnessed by the resurgence of early marriage in China despite laws against such practices.107

Another type of family exigency is debt or blood debt; in certain cultures, girls may be “gifted” to pay such a debt. In Afghanistan the tradition is known as baad, and it is estimated that more than 10 percent of marriages in that country stem from the practice. The Afghan Penal Code supposedly prohibits baad, but only for women over eighteen years old and widows. Virtually all those given in baad are young girls, however.108

The effects on girls of child marriage are devastating. We will argue in later chapters that the effects on the broader society are equally devastating. For the girls, however, gender and foreign policy expert Rachel Vogelstein notes they are “forced to leave their families, marry against their will, endure sexual and physical abuse, and bear children while still in childhood…it is tantamount to sexual slavery.”109 Woe unto the girl who wishes to escape her fate:

A child bride’s instinct to run away is often met with horrific consequences. If a child bride leaves her husband’s home, she risks retaliation from both her husband’s family and her birth family. For the bride’s family, having a daughter that has run away from her husband’s home brings shame onto the entire family. The bride’s virtue is automatically called into question, and she is labeled as promiscuous and disobedient. Ultimately, the perceived shame for the birth family will become unbearable, until finally, a male in the family will seek to bring back the family’s honor by killing the source of the pain: the young bride…Thirteen-year-old Yemeni child bride Ilham Mahdi al Assi died tragically three days after her wedding in April, after she was tied down, raped repeatedly and left bleeding to death. Another recent example is 12-year-old Fawziya Abdullah Youssef, also a Yemeni child bride, who died after three days of excruciating labor pain because her body wasn’t developed enough to give birth.110

Child marriage clearly does not serve the interests of the girls involved in terms of their physical health, opportunities for education, or level of safety within the household. As a United Nations Children's Fund report summarizes, “Child marriage is a violation of human rights, compromising the development of girls and often resulting in early pregnancy and social isolation. Young married girls face onerous domestic burdens, constrained decision-making and reduced life choices.”111

One of the most important feedback loops with in the Syndrome is between child marriage, brideprice or dowry, and violence against women. Vogelstein reports:

Data from India show that girls married at age eighteen or older are more likely to repudiate domestic violence, whereas those married under the age of eighteen are more likely to have experience with physical or sexual abuse. Girls married as children are also more likely to be physically abused not only by their husbands, but also by their family members and in-laws. Wide disparities in age and power between husband and wife, as well as marital financial transactions such as dowry and brideprice, can exacerbate social norms that sanction violence.”112

Child marriage produces many cascading effects on human and economic security, which we detail in chapter 6. World Bank economist Quentin Wodon summarizes them here:

By curtailing education, increasing fertility, and limiting opportunities for employment, child marriage contributes to poverty. The practice is also associated with a higher risk of intimate partner violence and other forms of violence, which may lead to severe injuries and even death, as well as losses in earnings and out-of-pocket costs for healthcare. Next, child marriage is associated with higher risks of…maternal mortality and morbidity…malnutrition and depression [and] poor sexual and reproductive health outcomes including through sexually transmitted diseases. The practice also has consequences for children in terms of infant mortality, low birth weight, and stunting. Finally, child marriage also leads to losses in empowerment and decision-making as well as participation more generally.113

But these statistics may obscure the sheer enormity of the human cost.114 As Stephanie Sinclair, the award-winning photographer whose photos of child brides put a shocking face to these statistics, reflects,

I first encountered child marriage in Afghanistan in 2003. I was horrified to learn that several girls in one province had set themselves on fire. After some investigation, it became apparent that one of the things propelling these girls to commit such a drastic act was having been forced to marry as a child. They told me they’d been married at 9, 10, 11—and in their misery [they] had preferred death over the lives they were living…. Every girl I met, in each country, completely broke my heart—particularly the ones married to much older men. The more I pursued the phenomenon, the more the issue continued to unravel before me. The trauma these girls carry with them into adulthood is utterly palpable when speaking with child marriage survivors about their experiences. These heroic women live their lives just like anyone else, but if they’re comfortable enough to discuss their past with you, the toll taken by such an intense childhood trauma becomes very, very clear. Then you take the experiences of the relative handful of girls and survivors I’ve met and then realize…with child marriage occurring in more than 50 countries worldwide, how many more girls are living a similar hell, day in and day out. The numbers are staggering! At least 39,000 girls married every day—that’s one girl every two seconds! Every day that goes by, an incomprehensible number of girls’ lives have been forever changed.115

And not for the better. As one health-care worker put it in Morocco, “This type of marriage is child rape; that is to say, her life has been raped by means of this marriage.”116 The incidence of child marriage is falling worldwide, except in Latin America where rates are rising.117 Even so, gains have been painfully slow. For example, a legal change in Morocco designed to reduce the number of girl-child marriages has unintentionally increased the number.118 Furthermore, as noted by Vogelstein, “The failure of some governments to implement systems of birth and marriage registration also makes it easier to avoid compliance with minimum age of marriage laws.”119 As we have seen, any type of exigency may catalyze child marriage for girls, for the Patrilineal/Fraternal Syndrome rigidly encodes their lower value as well as their higher risk to family honor. In November 2014, the Human Rights Committee of the United Nations General Assembly adopted by consensus a resolution calling on all nations to end child marriage and forced marriage. The resolution had 118 sponsors from across all continents—but the map at the beginning of this subsection tells the true tale.

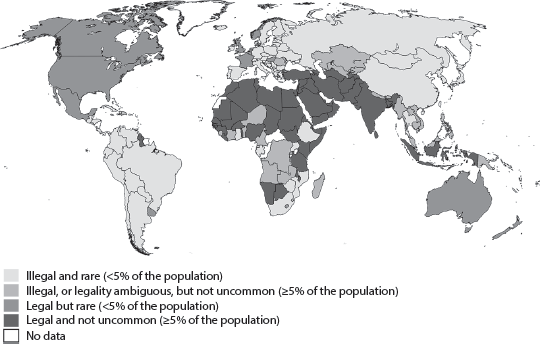

Cousin Marriage

Cousin marriage is common in some patrilineal societies as a way to keep assets within the family—that is, so that brideprice or dowry does not leave the family when a woman marries (figure 3.9).120 Reciprocal exchange of daughters between kin, or “bride exchange,” with marriage often to one’s father’s brother’s daughter, often occurs in this context to maintain roughly equal status between the cousins’ families, for in patrilineal societies, as Goody explains, “[There is a] strong tendency for the wife-receiving group to rank the higher.”121 Reciprocal exchange of women within the kin group prevents this status difference from emerging.

FIGURE 3.9 Map of Prevalence and Legality of Cousin Marriage, scaled 2016

Anthropologist Bernard Chapais and others believe cross-cousin marriage developed early in human society, perhaps even in the prelinguistic era. Interestingly, he posits its rationale is the construction of what he terms “affinal brotherhood,” that is, linking a brother (and his father) through the brother’s sister to her husband, maintaining affinity across the branches of the patriline. This brotherhood-through-marriage permits “male pacification,” by which Chapais means reduction in competition and violence between men “connected” by women.122 This brotherhood then forms the basis of the larger community, the agnatic tribe, whose boundaries are circumscribed by how far across the genealogical tree one may marry.

The presence of cousin marriage is a tip-off that patrilineality is present, for without patrilineality, there would be no incentive for it, especially given the genetic risks that are disproportionately present in cases in which cousin marriage is practiced. One Egyptian pediatrician asserts that 90 percent of the genetic diseases seen in children in that country are the result of consanguineous marriage, and include microcephaly, cystic fibrosis, thalassaemia, and previously unseen disorders.123 In the United Kingdom, where it is estimated that 60 percent of couples of Pakistani heritage are in consanguineous marriages, the death rate attributed to inherited disease was thirty-eight times that of reference couples.124 In Egypt, about 40 percent marry cousins, and rates are similar for Jordan and also the Gulf states. Iran’s rate of cousin marriage is approximately 37 percent.125 Across the MENA region as a whole, up to 50 percent of marriages may be consanguineous.126 The toll of misery from genetic disease is appallingly high in all these countries.

Even so, in Saudi Arabia, there is a saying concerning cousin marriage that, “a piece of fabric remains beautiful only if the additional fabric attached to it is from the same kind.”127 Abdul Al Lily describes how some Saudi tribes will reject marriage proposals from nonfamily members and even will decide on marriage partners from among the cousins for a child at the time of their birth. Oftentimes even an ominous genetic test result between cousins may not preclude the marriage.128

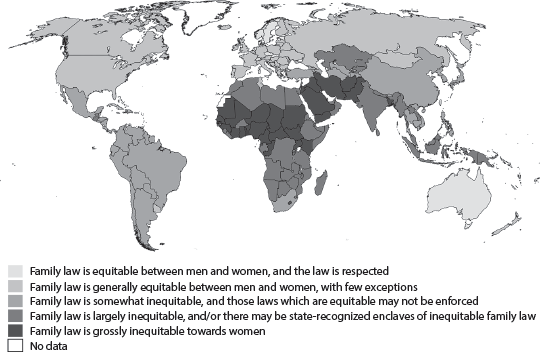

Cousin marriage not only is prevalent in MENA but also is practiced among some groups in South Asia. Hanan Jacoby and Ghazala Mansuri reference a 2004–2005 survey in the Pakistani provinces of Sindh and Punjab, finding that more than three-quarters of women had married a blood relative, typically a cousin.129 It is also not uncommon for cousin marriage to be reciprocal, that is, female cousins are exchanged between kin so that no money or assets need change hands, and even the women’s inheritances are kept within their birth families. (Sometimes such a “swap” can even take place between families that are not kin, although our scale of cousin marriage does not capture that practice.) “Swapping” women can sometimes be risky, however, because if one of the marriages ends in divorce, the other couple may be forced to divorce, as well—even if they are happy together—for reasons of honor.130 If one wife is killed through domestic violence, the other may be killed, as well, in retribution. An additional catalyst besides preservation of patriline assets is the often-fierce rivalry between male cousins, which this type of marriage is meant to ameliorate.131