CHAPTER 13

ENGINEERING IN PRE-SERVICE TEACHER EDUCATION

Steve O’Brien,1 John Karsnitz,1 Suriza Van Der Sandt,1 Laura Bottomley,2 and Elizabeth Parry2

1The College of New Jersey, 2North Carolina State University

ABSTRACT

This chapter provides a review of pre-service teacher preparation programs in engineering education, at both the elementary and secondary level. For elementary grades there are at least six universities with engineering education content purposefully taught in curriculum, though this number is likely increasing. At the secondary level, the field of technology and engineering education, with strong links to industrial arts, has historically been the provider of technology/engineering education pre-service teaching degrees. A history of important changes in the secondary pre-service certification path is given, including the adoption of more science, math, and engineering content.

INTRODUCTION

The inclusion of engineering content has grown rapidly in all levels of K–12 over the past ten years. For example, in K–5 grades Engineering is Elementary (EiE) curriculum has reached over five million students and 65,000 teachers, and is being used in all 50 states. Similarly, in grades 6–12, Project Lead the Way (PLTW) curriculum has reached over 400,000 students in over 5,000 schools in all 50 states. Engineering by Design (EbD) has also developed design-based curriculum for use in secondary grades and has recently developed K–5 curriculum. More detailed descriptions of K–12 engineering curricula are given in Chapters 3-7. Similar growth has also occurred for informal programs. For example, For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology (FIRST) has successfully promoted out-of-school robotics competitions in most states and at all levels of K–12, reaching over 200,000 students in over 50 countries. Part V of this book gives more detailed information on informal engineering activities. Motivations for implementing engineering curricula in K–12 certainly vary. For example, there are several recent studies that have indicated substantial benefits from engineering curriculum in K–12 (Brophy, Klein, Portsmore, & Rogers, 2008; Lachapelle & Cunningham, 2007; Lachapelle et al., 2011; Zubrowski, 2002; Koch & Feingold, 2006; Parry, Hardee & Day, 2012). Other research results are reviewed in more detail in Parts II-IV of this book. Such growth in engineering curricula raises important questions about teacher preparation in K–12 engineering education. Indeed, teacher training in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) education was a key recommendation in three recent reports: (i) Rise Above the Gathering Storm: Energizing and Employing America for a Brighter Economic Future (NRC, 2007), (ii) Rising above the Gathering Storm, revisited: Rapidly approaching Category 5 (NRC, 2010) and (iii) Engineering in K-12 Education: Understanding the Status and Improving the Prospects (Katehi, Pearson, & Feder, 2009).

Engineering curricula in K–12 involve content and teaching methodologies that are not taught or experienced in the large majority of teacher preparation programs. Engineering curricula include skills with the engineering design process, the concept of failure and failure analysis, iteration, open-ended problem solving, problem-based learning, multi/inter-disciplinary teaching methods (integration of multiple subjects, STEM and non-STEM), knowledge of materials, and materials processing and safety. This chapter addresses the current status of pre-service teacher preparation in technology and engineering education. Pre-service teacher preparation, due to both the large number of teacher candidates and the intensity of training (~4 years), is the key to having the most systemic impact on the effective teaching of engineering and STEM concepts, and likely non-STEM concepts, in K–12.

Understanding the engineered (human-designed) world is of particular utility when training future teachers, and perhaps specifically relevant for future K–5 teachers due to the breadth of their curriculum and their early placement in the educational process. Some potential benefits of including engineering education content in teacher preparation are as follows:

• Technology and engineering (T&E) content requires more analytical capability (math, science, and analysis-based problem solving). This is important in the current K–5 environment, since many teachers have only minimal math and science content experiences.

• T&E components provide an important context for math, science, and non-STEM subjects. T&E components provide motivation for students (and teachers), since they can effectively answer the often-asked question, “Why do we have to learn subject X?” When combined with effective open-ended problems, T&E activities provide an authentic (real-world) reason why math and science, and non-STEM subjects, are important in life. The motivation or contextual capability of integrating engineering also has an important link to the cognitive science of learning. Dolan (2002) gives an overview of the role of emotion (read “motivation”) in behavior and cognition.

• T&E activities involve design-based pedagogies, which directly infuse higher levels of knowledge and skills (Bloom’s Taxonomy) into the classroom, since these activities require design, analysis, critique, evaluation, and so forth.

• Since humans are largely surrounded by human-designed items, T&E content and activities serve as excellent integrators of subjects. As one example, Museum of Boston’s EiE curriculum integrates language arts literacy with engineering and science content and activities. In general, engineering content and activities can be integrated into multiple subjects, which can be a highly effective means of learning material. This important inter-relationship between the individual STEM components leads to the concept of “integrative-STEM,” a concept we believe was coined by Sanders (2009). The distinction between STEM and integrative-STEM is an important one for K–12 pedagogical activities (individual subjects versus inter/multidisciplinary approaches). (The term STEM typically has meant the use of any of the individual components, which does not bring in to play the integration of components.

• Effective teaching closely models the engineering design process. An engineer’s unique form of thinking and doing is based on design (problem solving under constraints). Engineering design is the practice of using a systematic approach in an iterative process to attain a goal, with testing, failure, and analysis as key components and tools to guide the process toward a viable solution. Effective teaching is not strictly prescriptive (memorization of rules, facts, or processes), but rather it is linked to a deeper level of capabilities rooted in the ability to solve problems through multiple solution pathways. A teacher in an effective teaching and learning environment will design the teaching and learning, using various types of pedagogical tools and assessments to optimize and change the process (“iterate”), resulting in the successful mastery of the learning objectives. Recent work has discussed a similar viewpoint by looking at teaching and teacher preparation as an iterative optimization process (Hiebert, Morris & Glass, 2003; Hiebert, Morris, Berk & Janson 2007). With engineering design as a central theme, teacher candidates (even non-STEM teacher candidates) might treat teaching more as a design process, and less as a prescriptive process.

• T&E content is valuable in its own right, resulting in higher STEM literacy. For example, the idea of “technology” being any result of human made design, as opposed to those ubiquitous handheld and desktop digital tools requiring power, is a paradigm shift for teachers, students, and for most citizens.

The beneficial impact of T&E content can also be put into a more detailed context by describing how T&E content potentially affects qualities of effective teachers. Many articles have discussed the qualities of effective teachers (Carey, 2004; Teaching Commission, 2004; Darling-Hammond, 2000, 2007). A list of Darling-Hammond’s five qualities of effective teaching is reproduced here: (1) strong general intelligence and verbal ability that help teachers to organize and explain ideas, as well as to observe and think diagnostically, (2) strong content knowledge up to a threshold level that relates to what is to be taught, (3) knowledge of how to teach others in that area (content pedagogy), in particular how to use hands-on learning techniques (e.g., lab work in science and manipulative tools in other subjects, such as mathematics) and how to develop higher-order thinking skills, (4) an understanding of learners and their learning and development, including how to assess and scaffold learning, how to support students who have learning differences or difficulties, and how to support the learning of language and content for those who are not already proficient in the language of instruction, and (5) adaptive expertise that allow teachers to make judgments about what is likely to work in a given context in response to students’ needs. T&E content knowledge and experiences can beneficially affect each of these five qualities of effective teaching (O’Brien, 2010).

This chapter is divided into two parts: (1) elementary education teacher preparation and (2) secondary education teacher preparation.

ELEMENTARY EDUCATION (GRADES K–5)

K–5 school years are crucial, setting the framework for all subjects as well as critical-thinking skills. However, in this formative timeframe, the number of K–5 teachers who are substantially educated with a STEM specialization is very small (Malzahn, 2013; Trygstad, 2013). A lack of STEM subject matter expertise and experiences, coupled with high anxiety and low self-efficacy can lead to low teacher effectiveness and lack of interest in STEM subjects by K–5 students (Wilkins, 2008; Beilock, Gunderson, Ramirez & Levine, 2010), especially for female students. Teachers with the ability to effectively integrate STEM (and non-STEM) subjects are even more scarce.

Standards for elementary education teacher preparation programs vary by state. However, in general K–5 teacher preparation programs typically require only minimal math and science: one to two math content courses, one science content course, and one or two math/ science methods courses. Rarely is technology and/or engineering (T&E) content required or even offered in K–5 teacher preparation programs, and very rarely are K–5 teachers trained deeply in STEM subjects (Malzahn, 2013; Trygstad, 2013). For example, only 4–5% of K–5 teachers have degrees or majors in math, science, or engineering, though it is important to note that this percentage has increased from 1–2% since 2002–03 (Malzahn, 2013; Fulp, 2002). A wide disparity was also apparent in the types of college science courses taken by K–5 teachers: life science (90%), earth or space science (65%), chemistry (47%), physics (32%), and engineering (1%). A portion of the reason why engineering in K–5 teacher preparation is uncommon, in addition to a scarcity of engineering education courses offered in K–5 programs, is likely linked to perceptions or even definitions of “engineering.” Many people assume that “engineering” only happens in postsecondary settings, as career preparation only, versus as a process used to solve problems more generally, and further that engineering must occur only in these college-preparation grades because high math and science skills are required. These assumptions are based on a general lack of knowledge of engineering both as a process and as a career. Human engineering was occurring well before the advent of higher-level science or mathematics. “Engineering” is at its base quite simple: human action to solve problems or address needs or wants under constraints and held to criteria of success. The central framework of engineering is design, and design-based pedagogy is fundamental to engineering education and integrative-STEM education.

Examples of engineering education in elementary teacher preparation programs

As mentioned earlier, engineering education is rarely required in K–5 teacher preparation programs. However, there are some important examples where engineering education is an intentional part of teacher preparation. T&E courses are offered at both the elective and the required level for both undergraduate levels (pre-service teachers) and graduate levels (primarily for in-service teachers). The following are brief descriptions of programs with intentional engineering education components. This list is not meant to be exhaustive but a sample.

• In 1998 The College of New Jersey (TCNJ) started a K–5 STEM major, referred to as the Math/Science/Technology or MST program. The name of this program was recently changed to Integrative-STEM or i-STEM. (The STEM acronym was not broadly used in 1998.) The i-STEM major has grown to be the largest education major on campus, with a total student count of approximately160, which represents 30–35% of the total K–5 education major population. The state of New Jersey requires a disciplinary major for all education majors, which made it relatively simple to design and implement a new disciplinary K-5 major. At TCNJ the i-STEM major is one of 11 possible disciplinary K–5 majors. To provide more content depth, the multi/interdisciplinary i-STEM program also requires each student to complete a specialization in math, science (biology, chemistry, or physics), or technology/engineering. Hence, the amount and type of STEM content varies for each student. However, all i-STEM graduates complete a high level of math, science, and T&E coursework, typically 60 credits of STEM content or methods courses. An i-STEM student takes 3–4 math courses (typically 4 math courses, and includes calculus), 1 math methods course, 3–4 science courses (typically 4 science courses), 1 science methods course, 3– T&E courses, and 1 i-STEM methods course. The i-STEM methods course is titled “Integrative-STEM for Young Learners,” which covers integrative teaching methods for both the inquiry (M&S) and design (T&E) components of STEM, problem-based learning (PBL) methods, and how to integrate STEM with non-STEM content. The majority of i-STEM majors satisfy course requirements for endorsements to teach middle school math and/or science. The i-STEM majors who choose the technology/engineering specialization can also satisfy course requirements for secondary K–12 technology education endorsement.

• North Carolina State University (NC State) has designed a course that is required of all elementary education students, entitled, “Children Design, Create and Invent” (ELM340). Topics in the course include the natural versus the designed world, K–5 education standards, integrative-STEM teaching and learning, designing educational activities, and experiences with existing K–5 engineering curricula. The course includes an abundance of hands-on and inquiry experiences that are also used to model this type of instruction for K–12 students. This course is taught by an adjunct engineering professor, co-appointed in the College of Education. In addition, the elementary education undergraduate program at NC State requires that students select a concentration of STEM or science. Students are required to take calculus, statistics, and five science courses. In addition to selecting a concentration area, the students complete required methods courses in all subject areas, with six credit hours in mathematics methods and six credit hours in science methods. A strong emphasis on technology and innovative digital instructional tools is incorporated into the program.

• Hofstra University offers undergraduate and master’s programs in STEM education. K–5 majors can take a STEM major in addition to their education coursework. The undergraduate STEM degree coursework is extensive and consists of five science courses, three math courses, and four T&E-oriented courses. The T&E courses are taught by a tenured professor in the Department of Engineering.

• St. Catherine’s University (St. Paul, MN) requires a STEM certificate for all elementary education majors (Ng & Maxfield, 2011). This certificate consists of three courses: Chemistry of Life, Environmental Biology, and Makin’ and Breakin’: Engineering Your World. These courses are co-taught with education and science faculty. St. Catherine’s also offers a STEM minor and a graduate nondegree certificate program.

• University of St. Thomas offers minor and graduate certificates in engineering education (Thomas, Hansen, Cohn, & Jensen, 2011). The first course in these programs is called “Fundamentals of Engineering for Educators,” which exposes students to content for a variety of engineering disciplines. Engineering, education and K–8 faculty were involved in the design of the course.

• Millersville University (MU) has recently designed and implemented a graduate course primarily for in-service teachers (Brusic, 2011). The course is entitled, “Teaching Technology in the Elementary Level.” Topics covered in this course are similar to T&E methods courses described earlier for NC State and TCNJ. However, the unique attribute about this course is that it was offered online. An online offering of “hands-on” engineering content certainly poses unique challenges, and perhaps some impossibilities. However, if online or blended courses could be designed to be effective, they may offer a means to widely disperse engineering education methods and content. In addition, by December 2013, MU intends to have a proposal ready for a five-course integrative-STEM concentration for PreK–4 elementary and early childhood majors, with the goal of starting the program by Fall 2015 (S. Brusic, personal communication, November 19, 2013).

Characterization data of engineering education programs

Even though more work needs to be completed, recently published works are showing some benefits of engineering education in K–5 (Brophy et al., 2008; Lachapelle & Cunningham, 2007, Lachapelle et al., 2011; Zubrowski, 2002; Parry et al., 2012). Additional references on this topic are given in a variety of chapters in this book. However, little work has been done in the area of characterizing the impacts of engineering education in K–5 teacher preparation. Should teacher preparation include T&E and integrative-STEM (including integration of STEM and non-STEM content), and if so, how is it best implemented? Not surprisingly, there is not a large amount of data that address the efficacy of teacher preparation programs that include T&E or integrative-STEM content. However there is some data, which are reviewed below.

The College of New Jersey

The i-STEM program requires a substantial amount of STEM content, and the program requires substantial coursework in all STEM components. The percentage of courses in each of the STEM areas depends on the students chosen specialization, but in general the i-STEM major requires 14 STEM content courses (3–8 being T&E courses) and 3 STEM methods courses (1 science, 1 math, and 1 integrative-STEM). A variety of quantitative characterizations have been completed on TCNJ’s pre-service K–5 i-STEM program (O’Brien, 2010; O’Brien, Van der Sandt, & Johnson, 2011). Brief summaries of these data are provided below.

Growth: The i-STEM major has shown substantial growth in the last 9 years, growing from approximately 5% of the total K–5 graduates in 2004 to approximately 33% in 2013. This is about a threefold increase, compared to the 8–13% total math and science K–5 graduates before the i-STEM program was established. From 2010 to 2013, the i-STEM major was the largest K–5 major and the largest overall education major.

Math and science testing: Analyses of i-STEM graduate performance on national PRAXIS exams indicated that competencies in math and science are statistically higher than non-STEM majors. Also of importance is that i-STEM graduates performed statistically equal to non-STEM majors on non-STEM test subjects of language arts and social studies.

Mapping to STL standards: A comprehensive set of national Standards for Technological Literacy (STL) were established in 2000 (International Technology Education Association [ITEA], 2000). The STL consist of 20 standards organized into five categories. Benchmarks are given for each of the 20 standards for four age groups; K–2, 3–5, 6–8, and 9–12. A mapping of the i-STEM curriculum onto the STL standards indicates that the curriculum provides 80–100% coverage for grades K–5.

Middle school endorsement: Due to the extensive level of math and science, most i-STEM graduates also qualify for middle school endorsements in math or science. Essentially 100% of the students complete one of these endorsements, and the large majority complete both endorsements. This endorsement opportunity encourages college students to take more math and science, but also aids in job placement.

Applied “engineering” math: Even though most TCNJ undergraduates have done well in previous mathematics courses and score high on the quantitative Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT), it was still the opinion of faculty that students were not skilled in applying math knowledge. Therefore, a course in applied math was added to the curriculum, with a majority of i-STEM majors completing the course. Preliminary characterizations of this course concerning subject interest and perceived anxiety were completed (O’Brien, 2011). Students were asked to gauge their level of interest in the subject matter both prior to and after taking the course. At the completion of the course about 30% of the “low interest” students were converted to “high interest.” This course also positively affected student perceptions in the following areas: (1) helping in becoming a better teacher, (2) understanding how math is used to affect our human existence, (3) helping in “everyday life” tasks, (4) making math skills better, and (5) improving comfort with mathematical tasks.

Math anxiety: Math anxiety was measured before and after two required math courses (O’Brien, Van der Sandt, & Johnson, 2011). The math courses were MAT105 (a K–5 math content course) and MTT202 (a K–5 math methods course). The K–5 teacher candidate population was analyzed by K–5 disciplinary major. Math anxiety improved significantly for non-STEM majors, but their anxiety level still remained high compared to K-5 STEM education majors. In contrast, the math anxiety level of i-STEM majors improved substantially, resulting in an anxiety level that was statistical equivalent to K–5 math majors, the local K–5 “golden standard” for low anxiety levels. The i-STEM major was the only major to accomplish this. The psychology major, a major that also requires a substantial level of context-driven quantitative content, exhibited the second highest improvements in math anxiety. A plot of anxiety levels for five populations of majors, relative to the (low) average anxiety level exhibited by math majors, is shown is Figure 13.1.

Figure 13.1. Math anxiety measurements for various grade K-5 disciplinary major populations, shown as a percentage above the average value observed for K-5 math majors. (Example: before MAT105 English (ENG) K-5 majors exhibited an anxiety level that was 30% higher than K-5 math majors.) Measures are shown for all four measurement points (Pre-MAT105, Post-MAT105, Pre-MTT202, and Post-MTT202) and five K-5 major populations: ENG (English), HIS (History), SO/WG (combined Social Studies and Woman & Gender Studies, PSY (Psychology), and i-STEM (integrative-STEM).

The anxiety data also gave indications that the integrative T&E portion of the i-STEM curriculum, which has highly contextualized applications of math and science, is having a beneficial impact. For example, the subpopulation of technology/engineering specialization i-STEM students, a population that takes substantially more T&E courses, showed the most dramatic improvements in anxiety, dominating the overall anxiety level average for the i-STEM population.

Using the upper quartile as a delineation point, the anxiety data showed that one in four non-STEM majors have high math anxiety after MTT202. The two majors with the highest percentage of high anxiety were English and History, with approximately 30% of these populations having anxiety levels in the upper quartile. This result is significant since the majority, approximately 65%, of TCNJ K–5 graduates are non-STEM majors, meaning that a large number of actual K–5 graduates are likely to have high math anxiety, which can negatively affect the quality of their teaching. At the national level these percentages, and raw numbers, of high anxiety in new teacher graduates may be much higher because (1) most K–5 teacher preparation programs across the United States are similar in design to TCNJ’s non-STEM major and (2) the average quantitative reasoning SAT score for TCNJ’s non-STEM K–5 major population is relatively high (~608) compared to the 2006–07 national average of about 480 for education schools. In comparison, only one in 14 i-STEM majors and no K–5 math majors had math anxiety levels in the upper quartile. Graduating a large percentage of future teachers with high math anxiety only further perpetuates math (and STEM) anxiety, since anxiety is passed on to the students, limiting the students’ affect and acumen in STEM subjects (Wilkins, 2008; Beilock et al., 2010).

North Carolina State University

The NC State engineering course, “Children Design, Create, and Invent,” for juniors in elementary education has been taught in its current form since 2009. Data collected so far are mostly anecdotal, but are reviewed here. In this course, one of the semester-long assignments is to choose a children’s book and design an activity related to engineering to complete with K–2 students. The college students wrote a proposal for the activity, then after instructor feedback, wrote a full lesson plan to show to their partner K–2 teachers. After the college students implemented their activity in the K–2 classroom, they wrote a summary of how the activity had gone and whether they would do anything differently. Some of the college students reported that either they or their partner teachers were unsure about whether the K–2 students would be able to complete the activity. All of the college students reported success after the activity, frequently to their and their partner teacher’s surprise.

The college students completed a self-reported assessment both prior to and after the completion of the semester. The following 11 questions were asked with answers recorded on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = disagree strongly, 5 = agree strongly): (1) I am confident in my science knowledge, (2) I am confident in my understanding of technology, (3) I am confident that I know what engineering is, (4) I am good at doing hands-on activities, (5) I am confident that I can do hands-on activities in a K–2 class, (6) I am confident that I can do hands-on activities in a 3–5 class, (7) I will have time for hands-on activities in my classroom, (8) I am confident in my ability to do problem solving, (9) I am confident that I can teach my class to problem solve, (10) I am confident of my ability to teach different types of children, and (11) The engineering design process can help me teach the Standard Course of Study (SCOS) to my class.

The college student responses to these questions were higher for each response after the course, as compared to before. Numerically, on average the responses after the course were approximately 50% higher (better) after the course. The average scores for questions 3 and 11 were more than twice as high after the course. A piece of anecdotal data is that 15% of students utilize engineering-oriented supplies and curriculum in lessons for their senior-year student teaching experiences. This 15% represents substantial growth from none just two years earlier.

Another activity spearheaded by an NC State College of Engineering staff member involved the use of Engineering is Elementary (EiE) curriculum in a K–5 school (Rachel Freeman School of Engineering). After completing sustained engineering education professional development and coaching for all teachers, Parry et al. saw substantial performance improvements in end-of-year testing (Parry et al., 2012). Test scores in reading, mathematics, and science, went from 34.4%, 43.4%, and 14.3%, respectively, in Year 1 to 62.1%, 74.6%, and 80.0% in Year 3. (Note: The school also added the “engineering” descriptor to the name of the school during the time of this interaction.) Teachers were also found to substantially use the design process for non-curricular activities. The model implemented at Rachel Freeman has been replicated with and without adaptions in four other North Carolina elementary schools as well as in several other states.

SECONDARY EDUCATION (GRADES 6–12)

The traditional means of providing formal T&E content in grades 6–12 has been through what is currently referred to as technology education or technology/pre-engineering education. A variety of universities across the United States graduate certified secondary teachers in this field. Technology/engineering education is a field with strong roots in industrial arts (1920s) and has undergone substantial changes over time. In the 1980s a coherent move toward national standards began, resulting in detailed benchmarks for technology and the designed world in Benchmarks for Scientific Literacy: Project 2061 (American Association for the Advancement of Science [AAAS], 1993) followed by even more detailed benchmarks in the Standards for Technological Literacy: Content for the Study of Technology (ITEA, 2000). An important inclusion in the Standards for Technological Literacy (STL) were expectations for skills with the design process, as opposed to simply “make and build” activities. More recently, some technology/engineering education teacher preparation departments have added more math, science, and engineering content to their pre-service curriculum, resulting in “pre-engineering,” “engineering,” or “STEM” being added to their titles. In 2010 ITEA recognized the inclusion of engineering education content into the field by changing their name to International Technology and Engineering Education Association (ITEEA). The national importance of the T&E in our education system, and society, is also indicated by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) taking on the design and delivery of a national test for technology and engineering literacy in grades 4, 8, and 12, with pilot tests planned with a sample of eighth graders in 2014. An interesting perspective on the current role of technology/pre-engineering education was recently given by Sanders (2011), and studies of technology/pre-engineering teacher production rates have been completed (Volk, 1997; Ndahi & Ritz, 2003), indicating that the production rate of technology education teachers is a concern.

Historical context

The lineage of the contemporary technology/engineering education in the United States can be traced back to the early 20th century. As the country was transitioning from an agrarian society to an industrial society, families moved from the farm to the city. On the farm, children worked with their parents, where they gained an understanding of appropriate skills related to the existing technologies. As families moved to the city, parents worked in industries where an understanding of existing technologies could not be directly taught to the children. To address this cultural problem, a new program called industrial arts began to emerge.

Industrial arts is the study of the changes made by man in the forms of materials to increase their value and of the problems of life related to these changes. (Bonser & Mossman, 1923, p. 5)

This statement is recognized as the first formal definition of the new field. Industrial arts was conceived to be a component of general education in which students would learn about the “arts of industry.” Students were to gain an understanding of these principles by making detailed drawings, sufficient to produce a desired product. Since most products of the time involved changing the form of wood and metal, students took their drawings into the shop, where they learned to use tools to make products. Instruction in industrial arts continued to be dominated by classes in drawing, woodworking, and metalworking through the first half of the 20th century.

Dissatisfaction with Traditional Industrial Arts Programs: By 1957 another big social change occurred in the United States; white-collar professional jobs outnumbered blue-collar industrial jobs. This meant that companies employed more workers to manage information about products than they employed to produce products. Historians have referred to this cultural shift as the Information/Technological Age. Concern began to be expressed that traditional industrial arts programs were not reflecting contemporary industry. Marshall Schmitt, Industrial Arts Specialist for the U.S. Department of Education, said, “the current industrial arts curriculum does not even measure up to the program recommended by the profession ten to 20 years ago” (Schmitt, 1967, p. 52–53). As stated in the Industrial Arts Curriculum Project (IACP) report,

Most such programs are based in turn-of the-century crafts and trades and call for students to make simple drawing and individual, custom-made projects in woodworking and in metalworking. Too often the processes, tools and equipment that are used are no longer relevant to activities in modern industry. (Lux, Ray, Buffer, Hauenstein, Jenkin & Sredl, 1969)

In 1965, the IACP received a major grant from the U.S. Department of Education to identify an organized body of knowledge and unifying themes that could be applied to all of industry. Recognizing a wide spread dissatisfaction with industrial arts, the staff of the project began a massive research effort over the initial 18 months, bringing together historians, philosophers, economists, sociologists, and specialists from across industry to create a rationale for the development of the curriculum. Three assumptions led the work:

• Industrial arts is the study of industry. It is an essential part of the education of all students in order that they may better understand their industrial environment and make wise decisions affecting their occupational goals.

• Man has been and remains curious about industry, its materials, processes, organization, research, and services.

• Industry is so vast a societal institution that it is necessary, for instruction purposes, to place an emphasis on conceptualizing a fundamental structure of the field, that is, a system of basic principles, concepts, and unifying themes (Towers, Lux, Ray & Stern, 1966, p. 2).

The project identified the four domains of human knowledge as (1) formal, (2) descriptive, (3) prescriptive, and (4) technological (identified as praxiological in the project). Technology can be viewed as hardware or artifacts, process, or knowledge. IACP defined technology as “the science of application of knowledge to practical purposes” (Towers, Lux, Ray, & Stern, 1966, p. 38). The project identified industry as the source of content that fell within our human-created economic system.

While there are considerable economic activities, including material and non-material production, the project created a matrix around construction and manufacturing goods production. For students to understand these important aspects of our economy, the staff created a three dimensional matrix consisting of (1) industrial management practices affecting humans and materials, (2) industrial production practices affecting humans and materials, and (3) industrial materials goods. The principles associated with these practices were codified and then used to create curricular materials for junior high school students, including two textbooks, The World of Construction and the World of Manufacturing, and supplemental student workbooks with daily laboratory-based activities and an extensive and prescriptive teacher’s guide. The intention was not to fully train individuals for industrial jobs, but give them a familiarity with industry. As stated in the IACP,

Upon completion of these courses, students are not expected to have acquired sufficient skill to be carpenters, civil engineers, architects … but they will be familiar with the problems and methods of these and many other workers and the interdependent roles of men in industry… . Some may decide not to enter industry. But even that decision will then be based on a more accurate knowledge of industry… . Regardless of the occupation one chooses, he should be able to make more intelligent decisions regarding the social and economic issues and problems created by industrial technology. (Lux, Ray, Buffer, Hauenstein, Jenkin, & Sredl, 1969, p. 12)

The IACP was promoted nationally and required schools to schedule each course for one period per day for the entire school year. Principles and design activities created by the joint IACP project team (Ohio State University and University of Illinois-Champaign) had an enduring impact in the field. Other leaders were also calling for change in the field. Donald Maley of the University of Maryland proposed a K–12 technology education program based on the study of technology and industry with implications for man and society. Called the Maryland Plan, the curriculum placed an emphasis on the psychological and sociological needs of the individual. The program focused on the integration of mathematics, science, communications, and the social sciences into the industrial arts activities. Teachers were to incorporate community resources and expanded reading materials, and use inquiry, problem solving, and experimentation to help student arrive at solutions (Maley, 1973)

Paul DeVore of the University of West Virginia established the nation’s first Department of Technology. In Technology: An Intellectual Discipline, he wrote that technology was “an area of study essential to an understanding of man and his world” (DeVore, 1964, p. 5). To gain this understanding he noted the field should “divorce themselves from such transient considerations as crafts, trades, handicrafts, purely manual skill, materials or isolated processes” (p. 7) and focus rather on enduring themes, including humans as builders, communicators, producers, transporters, developers, organizers and managers, and craftsmen.

Kenneth Brown at SUNY Buffalo, recognized as the first member of the Academy of Fellows of the American Industrial Arts, also made substantial impacts. In his monograph Model of a Theoretical Base for Industrial Arts Education (Brown, 1977), Brown identified three possible themes, with the “Technology” theme as a preferred “general education” path (as opposed to a vocational path). The other two themes were The Mechanical Trades (“tool skills”) and American Industry (organization and operation of industry).

Transitioning to Technology: By the 1980s, some programs were beginning to focus on technology as the study of the human-designed world. This philosophical shift was influenced by technology initiatives in Europe and England and the Science, Technology, and Society (STS) movement in the United States. The Sloan Foundation began to fund technological literacy programs, primarily in liberal arts colleges. Colleges such as The College of New Jersey (formally Trenton State College) established a new college-wide goal for technological literacy and created a core society, ethics, and technology (SET) course, required of all students, not only technology education students. Some programs began to focus on design as a unique form of human activity that leads to solutions in technology and engineering, although little emphasis was placed on engineering principles. The STS movement encouraged programs to look at the impact of technological activity on the human-designed world. Many curricula began to broaden the area of study to include not only construction and manufacturing, but also transportation, communication, and power and energy.

National Standards Movement: The publication of the Benchmarks for Scientific Literacy in 1993 (AAAS, 1993) identified a long-term initiative to reform K–12 education in natural and social science, mathematics, and technology. This report identified, for the first time, benchmarks for the study of technology. Separate panels prepared papers on what students needed to know in each of the areas under question. The study of technology included benchmarks under Chapter 3 “The Nature of Technology” and Chapter 8 “The Designed World.” All subjects were integrated in chapters calling for an understanding of human society, historical perspectives, common themes, and habits of the mind. Technology educators were encouraged to include principles of interrelationships between technology and science, design and systems, and contemporary issues. “The Designed World” focused on having students learn principles in agriculture, materials and manufacturing, energy sources and use, communication, information processing, and health technologies.

Another important milestone was the National Science Foundation’s announcement for material development, research, and informal science programs in 1991, which made funds available for the first time in technology education:

[A] third area of special attention is that of technology education. In this sense, technology is not an instrument, but a field of study. It involves the application of learned principles to specific, tangible situations. Problems in technology typically consist of three components: a given set of resources, given conditions or constraints, and stated goals. Because these design under constraint problems have multiple solutions, students and teachers become focused on the process of problem solving; therefore, rather than constantly being faced with situations which can only result in success or failure, students experience situations in which each outcome offers some opportunity for learning. In using this approach, students not only learn techniques of design and engineering, but also receive practical problem solving experience in the principles of mathematics and science. (NSF, 1991, p. 3)

The Standards for Technological Literacy: Content for the Study of Technology (STL) was published in 2000 by the International Technology Education Association (ITEA, 2000). The standards were written by the Technology for All Americans Project and reflected much of the work previously published by Project 2061. STL established what students should know and be able to do in order to achieve technological literacy. The standards did not, however, establish a curriculum for the field. The standards were organized around five major themes: the nature of technology, technology and society, design, abilities for a technological world, and the designed world. Design is the main theme of the STL, which outline a detailed 12-step design process. The STL included design for the first time in national standards and spoke to the role of engineering design, although not as a major component of the standard. The designed world standard was organized around medical technologies, agricultural and related biotechnologies, energy and power technologies, information and communication, transportation technologies, manufacturing technologies, and construction technologies. Both the Benchmarks for Science Literacy and the STL have had a significant influence on the development of core T&E content standards in the United States.

Influence of engineering principles on the study of technology

Two recent curricula have influenced the incorporation of substantial engineering activities in grades 6–12: Project Lead the Way (PLTW) and Engineering by Design (EbD).

Project Lead the Way (PLTW): PLTW is a not-for-profit organization partnering with public schools, private organizations and corporations, and higher education institutions to provide curriculum in STEM education. Gateway to Technology (middle school curriculum) is designed as five independent, nine-week units for grades 6–8, in which students can explore design and modeling, the magic of electrons, the science of technology, automation and robotics, and flight and space. Pathway to Engineering (high school curriculum) offers indepth, hands-on learning, with foundation courses in Introduction to Engineering Design, Principles of Engineering, and Digital Electronics. PLTW has a network of 500 core trainers, as well as association with 100 higher education institutions, to provide training in K–12 engineering education and work with school districts to provide a rigorous curriculum. PLTW has established pre-service affiliates in colleges and universities with technology education programs that have established protocols to pre-certify teachers for PLTW teaching positions. PLTW curricula also include several specialized courses, including biomedical, aerospace, computer science and civil engineering.

Engineering by Design (EbD): EbD is a K–12 national model developed by ITEEA’s STEM Center for Teaching and Learning. These integrative units were created to provide an outline for the teaching of technological literacy to all. By providing such a program, ITEEA believed that they could assist in restoring American leadership in innovation by leading students to become the “next generation of technologists, innovators, designers and engineers.” EbD is a standards-based model technology program built on the STL (ITEA, 2000), the Principles and Standards for School Mathematics (NCTM), and the Project 2061 Benchmarks for Science Literacy. The clusters begin in grades 2–3, with 3-hour units, and progress to full 36-week courses in grades 11 and 12. The program is built on the constructivist model in which students’ competence builds over time. EbD also has online assessments available, enabling curriculum evaluation. Approximately 20 states have joined a consortium for EbD curriculum.

Current review of pre-service teacher preparation

Historically teachers have been trained through state-certified technology and engineering education teacher preparation programs at colleges and universities. The certification process is conducted by the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE), whose standards are primarily influenced by the STL. Teacher preparation programs reached their zenith in size during the 1960s when demand was high. Currently, pre-service institutions are not producing enough technology/pre-engineering teachers (Volk, 1997; Ndahi & Ritz, 2003). A variety of mechanisms will hopefully turn this trend around: (1) the widespread adoption of engineering curriculum and standards in K–12 (including Next Generation Science Standards), (2) the adoption of 21st-century skills standards by states, (3) a rapidly growing number of engineers specializing in engineering education (through organizations such as the American Society for Engineering Education [ASEE]) who conduct significant research and practice specifically in the K–12 space; (4) the proliferation of informal learning activities like FIRST robotics and many other engineering-centric activities/competitions, (5) research results of the impacts of engineering education in K–12, (6) national marketing efforts, (7) employment opportunities, and (8) alternative certification paths such as “Masters in the Art of Teaching” (MAT) degrees that are attracting individuals already holding bachelor degrees in design fields.

To provide a cursory view of technology education teacher preparation programs across the United States, in Spring 2011 the authors reviewed published online curricula for the baccalaureate level teacher preparation programs for schools listed in the 2011 Directory of ITEEA Institutional and Museum Members (International Technology and Engineering Education Association [ITEA], 2011). Program information was available for 32 programs in 27 states. (A similar, but more detailed, review of engineering content in technology programs was recently published by Fantz and Katsioloudis [2011].)

Program summary information included program name, institution, and school organization; mathematics and science requirements; technology courses; and professional courses. Technology courses were subdivided into STL and non-STL categories. No attempt was made to identify liberal learning requirements beyond the required mathematics and science courses. Technology and professional studies components were included by credit requirements. A small number of institutions listed some courses as “Teaching of <content area>” (i.e., Teaching Transportation). For the purposes of this study, these courses were included under the content category. When the mathematics or science requirements were not clearly identified, the program was contacted for additional clarification. Mathematics courses were classified as algebra/trigonometry, pre-calculus, or calculus, while science courses were classified as either general science (lower level) or principles (higher level).

From the data collected it is clear that teacher education programs are primarily based on technology as a study of the human-designed world, organized around categories identified in the STL. All programs have the word “technology” in their title. In addition, 22% of the programs included the word “engineering” in their titles. Department names such as “Technology & Engineering Education” at Central Connecticut State University or program names like “Technology/Pre-Engineering Education” at The College of New Jersey were typical. Approximately 10% of the programs were housed within the school of engineering, an indication of an especially strong link to engineering. A title of “Technology & Industrial Arts” was used by only one program. This review of programs suggests that no program has a primary focus on the older industrial arts lineage.

An analysis of the academic requirements found that 22% of the STEM-oriented course-work was in science and mathematics, with the remaining 78% in technology and engineering. Only 3% of the programs’ courses listed had “engineering” in the title. However, it is difficult to determine the amount of emphasis on engineering principles by looking at course titles. For example, a course entitled “Structures and Mechanisms” at TCNJ requires substantial engineering and analytical-driven design but does not have “engineering” in the title.

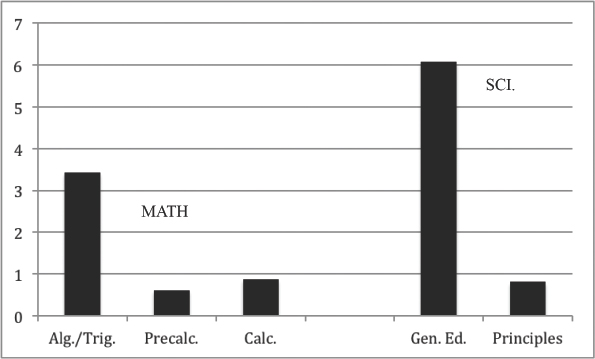

One method of investigating the engineering or analytical rigor of a program is to assess the level of math and science required. While most programs required two mathematics and two science courses, the courses were primarily at the lower levels, which may not have sufficient rigor for more challenging engineering-focused STEM studies. For example, only 10% of the mathematics courses were at the calculus level and only 7% of the science courses taken were at the higher “principles” level. Figure 13.2 shows the average number of credits in math and science, of varying levels, required by the 32 programs assessed. From this data it is apparent that most programs do not require higher levels of math or science.

Figure 13.2. Average required credits for math and science, at various levels, for the 32 T&E education programs analyzed.

Several programs have required additional, and higher level, math and science courses. For example, The College of New Jersey requires several additional math and science requirements: Calculus-I, Physics-I (calculus-based), one non-physics science course, and an applied math course designed by their department. In addition, in 2012 Utah State University required two calculus courses and two calculus-based physics courses, but that requirement has since been relaxed to one calculus course and a few non-calculus based physics courses (K. Becker, personal communication, November 18, 2013).

The technology content in the programs appeared to be strong, with a major emphasis on courses organized around STL themes, including content in the nature of technology, technology and society, design, abilities, and designed world. Most emphasis was placed on information/communications (13%), CAD (9%), manufacturing (9%), materials (9%), and construction and design (7%), where the number in parentheses is the percentage of the total T&E curriculum. No course was found in medical technologies and coursework in agricultural/bio-related technologies was found in only 2% of the programs, which is surprising considering the importance of these fields to society.

Nearly one half (43%) of all program requirements were in education. These courses included courses taken in the school of education and the technology education department. Some additional courses such as psychology are typically required as part of the liberal learning component of a program, which was not considered in the study. When considering the STEM studies and education courses, programs averaged 13% mathematics/science, 45% technology, and 43% education requirements.

Often a field can be represented by the kinds of academic material available for teaching the content. Following, in alphabetical order, is a brief list of books used in K–12 engineering courses or T&E education teacher preparation:

• Brusic, S. A., Fales, J. F., & Kuetemeyer, V. F. (2008). Technology: Engineering and Design (6th Ed.). Glencoe McGraw-Hill. ISBN13: 978–0-07–876809–5

• Burghardt, D., Hacker, M. (2004). Technology Education Learning by Design. Prentice-Hall. ISBN10: 0130363502

• Burghardt, D., Hacker, M., & Fletcher, L. (2009). Engineering and Technology. Cengage Learning. ISBN13: 978–1-41–807389–3

• Handley, B., Coon, C., & Marshall, D. (2012). Principles of Engineering. Cengage Learning. ISBN13: 978–1-43–542836–2

• Harms, H., & Swenofsky, N. (2002). Technology Interactions. McGraw-Hill Publishing. ISBN10: 0078297265

• Karsnitz, J., & Hutchinson, J. (1994). Design and Problem Solving in Technology. Delmar Publications. ISBN13: 978–0-82–735244–5

• Karsnitz, J., O’Brien, S., & Hutchinson, J. (2008). Engineering Design: An Introduction. Cengage Learning. ISBN13: 978–1-41–806241–5

• Lidwell, W. Holden, K., & Butler, J. (2010). Universal Principals of Design: 125 Ways to Enhance Usability, Influence Perception, Increase Appeal, Make Better Design Decisions, and Teach through Design. Rockport Publishers, Inc. ISBN13: 978–1-59–253007–6

• Matteson, D., Kennedy, D., & Baur, S. (2012). Civil Engineering and Architecture. Cengage Learning. ISBN13: 978–1-43–544164–4

• Petrovsky, H. (1996). Invention by Design: How Engineers Get from Thought to Thing. Harvard University Press. ISBN-13: 978–0-67–446368–4

• Petrovsky, H. (1992) To Engineer is Human: The Role of Failure in Successful Design. Vintage Books. ISBN-13: 978–0-67–973416–1

• Petrovsky, H. (2008). Success Through Failure: The Paradox of Design. Princeton University Press. ISBN-13: 978–0-69–113642–4

• Winston, M., Edelbach, R. (2003). Society, Ethics and Technology. Thomson Wadsworth. ISBN13: 978–1-11–129816–6

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

This chapter gives an overview of the current pre-service training in engineering education in the United States. The chapter was divided into two sections: grades K–5 and 6–12. Engineering education components in K–5 pre-service programs are a relatively new addition to teacher preparation. However, formal K–5 T&E-based programs date back to 1998. Pre-service K–5 programs that had some emphasis on T&E or integrative-STEM were reviewed, including The College of New Jersey, North Carolina State University, Hofstra University, St. Catherine’s University, and University of St. Thomas. Some data have been published that characterize the effectiveness and impact of T&E curriculum in K–5 teacher preparation. TCNJ’s K–5 program requires a substantial level of engineering components and has grown to become the largest K–5 education major at the college. Measurements indicated low levels of math anxiety and high levels of math self-efficacy for TCNJ i-STEM students, indicating that integrative-STEM teacher preparation programs can produce teachers who are comfortable and capable of teaching STEM content. This is especially important in grades K–5 due to the breadth of subjects taught by teachers, as well as the need for a strong foundation in STEM subjects in preparation for grades 6–12. NC State’s K–5 program is also unique in that one engineering content and methods course is required for all K–5 majors. The success of the STEM-based K–5 teacher preparation programs reviewed here, along with recent studies of the beneficial impacts of K–5 engineering curricula, strongly suggest that modifications to current K–5 teacher preparation systems be considered. Recent science standards (e.g., Next Generation Science Standards) mirror this thought and include some engineering components (design-pedagogy).

For grades 6–12, there is an established means for training T&E capable teachers, currently referred to as technology education or technology and pre-engineering education. T&E education training is rich in the content and pedagogy associated with human design and the impact of human design activity on the individual, society, and environment. Contemporary T&E education programs reflect their historic lineage to industrial arts (“The Arts of Industry”), but are currently based on T&E principles with a strong correlation to the design-centric content defined in the Standards for Technological Literacy. There are multiple indications that there is an increased emphasis on engineering principles in teacher preparation programs. However, it was evident that few programs required the higher level mathematics and science courses that would be necessary requisite knowledge for more rigorous engineering design activities in grades 9–12. Important future paths for T&E teacher training in grades 6–12 would be to (1) incorporate higher levels of math and science (and engineering), (2) continue research into the effectiveness of T&E components on STEM (and non-STEM) learning, and (3) produce more teachers to fill a shortage of T&E education teacher positions.

POSSIBLE FUTURE RESEARCH

There are perhaps three general categories of research that would affect the mission of pre-service programs.

Benefits to K–12 students: A deep understanding of the benefits, both quantitative and qualitative, of T&E components (integrative-STEM components in general) on K–12 students and the best methods for achieving the benefits (curriculum/methods). The fundamental goal may be to define a framework for engineering in K–12 and how engineering interacts with other subjects and goals (math, technology, science, 21st-century skills, gender equity, etc.).

Teacher training: An understanding of the content and skills that are preferred for a teacher and how these T&E content and skills are best imparted. This would not only affect content courses, but also require modification to methods taught to pre-service teachers.

Impacts on the educational system: The impacts on and capabilities of K–12 schools, colleges and universities, and governments agencies are important. This could include impacts on certification requirements, K–12 standards, pre-service training, in-service training, student assessment, and teacher assessment.

REFERENCES

American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). (1993). Benchmarks for science literacy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Beilock, S. L., Gunderson, E. A., Ramirez, G., & Levine, S. G. (2010). Female teachers’ math anxiety affects girls’ math achievement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(5), 1860–1863.

Bonser, F. G., & Mossman, L. C. (1923). Industrial arts for the elementary schools. New York: Mac-Millan Company.

Brophy, S., Klein, S., Portsmore, M., & Rogers, C. (2008). Advancing engineering education in P-12 classrooms. Journal of Engineering Education, 97(3), 369–387.

Brown, K. W. (1977). Model of a theoretical base for industrial arts education. Washington, DC: American Industrial Arts Association.

Brusic, S. A. (2011). An elementary online course: Strategies and reflections. Proceedings of the 73rd Annual Conference of the International Technology & Engineering Educators Association (ITEEA). Minneapolis, MN.

Carey, K. (2004). The real value of teachers: Using new information about teacher effectiveness to close the achievement gap. Thinking K-16, 8(1), 1–42.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). Solving the dilemmas of teacher supply, demand, and standards: How we can ensure a competent, caring, and qualified teacher for every child. New York: National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2007). Recognizing and enhancing teacher effectiveness: A policy maker’s guide. Washington, DC: Council for Chief State School Officers.

DeVore, P. D. (1964). Technology: An intellectual discipline. Bulletin Number 5. Washington, DC: American Industrial Arts Association.

Dolan, R. J. (2002). Emotion, cognition and behavior. Science, 298(5596), 1191–1194.

Fantz, T. D., & Katsioloudis, P. T. (2011). Analysis of engineering content within technology education programs. Journal of Technology Education, 23(1), 19–31.

Fulp, S. L. (2002). 2000 National survey of science and mathematics education: Status of elementary school science teaching. Retrieved from: http://www.horizon-research.com/reports/?sort=report_category

Hiebert, J., Morris, A. K., Berk, D., & Janson, A. (2007). Preparing teachers to learn from teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 58(1), 47–61.

Hiebert, J., Morris, A. K., & Glass, B. (2003). Learning to learn to teach: an “experimental” model for teaching and teacher preparation in mathematics. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 6, 201–222.

International Technology Education Association (ITEA). 2000. Standards for technological literacy: Content for the study of technology (1st ed.). Reston, VA: ITEA.

International Technology & Engineering Education Association. (2011). Directory of ITEEA institutional and museum members. Technology and Engineering Teacher, 50(April).

Katehi, L., Pearson, G., & Feder, M. (Eds.). (2009). Engineering in K-12 education: Understanding the status and improving the prospects. Committee on K-12 Engineering Education. National Academy of Engineering, National Research Council. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Koch, J., & Feingold, B. (2006). Engineering a poem: An action research study. Journal of Technology Education, 18(1), 54–65.

Lachapelle, C. P., & Cunningham, C. M. (2007). Engineering is Elementary: Children’s changing understandings of science and engineering. Proceedings of the American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference and Exposition. Honolulu, HI.

Lachapelle, C. P., Cunningham, C. M., Jocz, J., Kay, A. E., Phadnis, P., & Sullivan, S. (2011). Engineering is Elementary: An evaluation of year 6 field testing, Proceedings of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching’s Annual International Conference. Orlando, FL

Lux, D. G., Ray, W. E., Buffer, J. J., Hauenstein, A. D., Jenkin, J. D. & Sredl, H. J. (1969). Industrial Arts Curriculum Project. Journal of Industrial Arts Education, (November-December), 1–12.

Maley, D. (1973). The Maryland plan. New York: Benziger Bruce and Glencoe.

Malzahn, K. A. (2013). 2012 National survey of science and mathematics education: Status of elementary school mathematics teaching. Retrieved from http://www.horizon-research.com/reports/?sort=report_category

National Research Council (NRC). (2007). Rising above the gathering storm: Energizing and employing America for a brighter economic future. Committee on Prospering in the Global Economy of the 21st Century: An agenda for American science and technology; Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

National Research Council (NRC). (2010). Rise above the gathering storm, revisited: Rapidly approaching category 5. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

National Science Foundation (NSF). (1991). Announcement for material development. Washington, DC: Research and Informal Science Programs.

Ndahi, H. B., & Ritz, J. M. (2003). Technology education teacher demand, 2002–2005. Technology Teacher, (April), 27–31.

Ng, Y., & Maxfield, L. R. (2011). Educating elementary teachers in engineering: A design method and baseline. Proceedings of the American Society for Engineering Education (ASEE) Annual Conference. Vancouver, BC, Canada.

O’Brien, S. (2010). A unique STEM K-5 teacher preparation program. Proceedings of the American Society for Engineering Education (ASEE) Annual Conference. Louisville, KY.

O’Brien, S. (2011). Applied math curriculum for elementary and secondary integrated STEM teacher preparation programs. Proceedings of the American Society for Engineering Education (ASEE) Annual Conference. Vancouver, BC, Canada.

O’Brien, S., Van der Sandt, S., & Johnson, E. (2011). Math anxiety and math teaching beliefs of a K-5 integrated-STEM major compared to other teacher preparation majors. Proceedings of the American Society for Engineering Education (ASEE) Annual Conference. Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Parry, E. A., Hardee, E. G., & Day, L. D. (2012). Developing elementary engineering schools: From planning to practice and results. Proceedings of the American Society for Engineering Education (ASEE) Annual Conference. San Antonio, TX.

Sanders, M. (2009). STEM, STEM education, STEMmania. The Technology Teacher, (Dec./Jan.), 20–26.

Sanders, M. (2011). Engineering in technology education. Proceedings of the American Society for Engineering Education (ASEE) Annual Conference. Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Schmitt, M. L. (1967). Present. Journal of Industrial Arts Education, 26(3), 52–54.

The Teaching Commission. (2004). Teaching at risk: A call to action. New York: The CUNY Graduate Center.

Thomas, A., Hansen, J. B., Cohn, S. H., & Jensen, B. P. (2011). Development and assessment of an engineering course for in-service and pre-service K-12 teachers. Proceedings of the American Society for Engineering Education (ASEE) Annual Conference. Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Towers, E. R., Lux, D. G., Ray, W. E., & Stern, J. (1966). A rationale and structure for industrial arts subject matter. Washington, DC: U.S. Office of Education, Bureau of Research, Division of Adult and Vocational Research.

Trygstad, P. J. (2013). 2012 National survey of science and mathematics education: Status of elementary school science teaching. Retrieved from: http://www.horizon-research.com/reports/?sort=report_category

Volk, K. S. (1997). Going, going, gone? Recent trends in technology teacher education programs. Journal of Technology Education, (2), 66–70.

Wilkins, J., L., M. (2008). The relationship among elementary teachers’ content knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and practices. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 11, 139–164.

Zubrowski, B. (2002). Integrating science into design technology projects: Using a standard model in the design process. Journal of Technology Education, 13(2), 48–67.