Some Preliminary Observations about Jurisprudence

Constructing a jurisprudence for a democracy is a daunting task. It requires the framing of issues so that citizens can make the substantive choices and weigh the competing values. Efforts are now under way in many newly free (or freer) nations—from the former Soviet Union and its satellites to Iraq to the Palestinian Authority to China—to draft constitutions, codify laws, and create processes for resolving disputes. There are also efforts all around the world to devise rules governing new and changing phenomena, such as the Internet, DNA and cloning, outer space, artificial intelligence, and other technological innovations. Though no jurisprudence is ever without roots in existing or prior law, and therefore no jurisprudence is ever built from scratch, each of these efforts at building a jurisprudence on the foundations of existing law involves something new, something that has changed, something that could not easily have been anticipated.

What is remarkable about the absence of a jurisprudence governing preemptive or preventive governmental action is that these phenomena are as old as recorded history. We have been practicing preemption and prevention for millennia. The philosophers, legal scholars, religious leaders, and politicians have seen these phenomena in action. Yet no systematic jurisprudence in any way comparable to the jurisprudence governing responses to past harms has emerged. Nor can this absence be fully attributed to the sage observations by Roscoe Pound quoted near the beginning of the book, that juristic theories come after lawyers and judges have dealt with concrete cases and learned how to dispose of them. It is certainly true that laws tend to grow out of experience and are not a priori postulates. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., was correct in his observation that “the life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience.”1 But the world has had considerable experience, both positive and negative, with preemptive and preventive governmental actions of many types. Legal systems have long “dealt with” and “disposed of” claims growing out of such actions.

The results have not always been satisfactory, but that is in the nature of the development of law. Jurisprudence grows largely out of mistakes. The proverb that “Good laws come from bad lives” may overstate the case somewhat, but there is certainly some truth to the observation that good deeds done by good people do not generate the kinds of legal controversies on which the law is built. The common law is a never-ending history of errors and anachronisms corrected over time. Precedent has a vote but not a veto. As Holmes once quipped, “It is revolting to have no better reason for a rule of law than that so it was laid down in the time of Henry IV. It is still more revolting if the grounds upon which it was laid down have vanished long since, and the rule simply persists from blind imitation of the past.”2 Human beings learn from their mistakes. To paraphrase George Santayana, those who cannot learn from the past are condemned to repeat it.3

I have argued elsewhere, in detail, that “rights come from wrongs”—“from human experience, particularly experience with injustice.”4 This point can be generalized beyond rights: Jurisprudence comes from experience, particularly negative experience. We build jurisprudence on the tragedies of the past in order to avoid their recurrence. Even in the Bible, the Ten Commandments of Exodus are preceded by the narratives of Genesis, narratives that described lawless human beings struggling to be just in the absence of rules or even role models. The jurisprudence of Exodus is built on the mistakes made by Cain, Lot, Abraham, Jacob, Joseph, even God in the narratives of Genesis.5

That is why I have waited until the final chapter to try to construct even a preliminary and tentative jurisprudence of preemption and prevention because it is essential first to narrate and critically to assess the history of these concepts, both ancient and modern. Nor is it possible to construct a full-blown and enduring jurisprudence even after a thoughtful review of the past. Jurisprudence is always a work in progress, based on assessments and reassessments of past experiences coupled with adaptations to ongoing experiences. Roscoe Pound put it well: “Law is experience developed by reason and applied continually to further experience.”6 Gods may be capable of revealing an enduring set of eternal laws from mountaintops, but humans can only struggle to cobble together ever-changing best efforts at regulating conduct through imperfect legislation and judicial interpretation.7 Such efforts rarely produce perfect rules that are cost-free, but rather compromises that seek to balance costs, benefits, and other moral considerations. A Midrash has Abraham telling God, “If you want the world to exist, you cannot insist upon complete justice; if it is complete justice you want, the world cannot endure.”8 Jurisprudence is an imperfect and dynamic process, not a static result. The struggle to balance liberty and security never stays won.

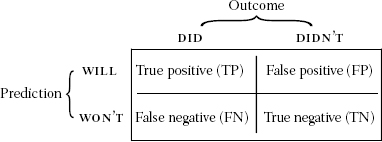

Among the components of any jurisprudence are the mechanisms for making the kinds of balancing decisions that will inevitably be required; the checks and balances on any such mechanisms; a recognition that errors will inevitably be made; principles for weighing the costs of different types of errors in different contexts (false positives, false negatives); methods for allocating burdens of going forward and burdens of proof; default rules in situations of equipoise; consideration of absolute (or relatively absolute) prohibitions on, or requirements of, certain actions; efforts to integrate new jurisprudential rules into the traditional jurisprudence; processes for evaluation, reevaluation, and change of rules; theories of human action, of sanctions and of the values of life, security, and liberty; the inevitability of unintended consequences, unanticipated events, and unknown elements.

What is not needed to construct a jurisprudence in a diverse democracy is a singular philosophy. Nations or groups that have rested their jurisprudence on a single philosophical, religious, political, or social “truth” have tended toward tyranny. We should not strive for the uniformity of one absolutely correct morality, truth, or justice. I am speaking not of scientific or empirical truth, which may well be singular and uniform (though always subject to challenge and reformulation), but rather of moral truth, which is not nearly as objective. It does not follow from the absoluteness of empirical truths that there are absolute moral truths. The confusion grows, at least in part, out of traditional religions, which are based on assumed empirical truths—Moses received the commandments at Sinai, Jesus was resurrected, Muhammad ascended to heaven on his horse—and seek to derive from these alleged empirical truths such absolute moral truths as “Thou shalt not kill.” But the absoluteness of moral truths is generally in the mind of the beholder. There are few, if any, moral truths (beyond meaningless platitudes) that have been accepted in all times and places. The active and never-ending processes of moralizing, truth searching, and justice seeking are far superior to the passive acceptance of one truth. The jurisprudencing process, like the truthing process, is ongoing. Indeed, there are dangers implicit in accepting, and acting upon, any one philosophy or morality. Conflicting moralities serve as checks against the tyranny of singular truth. I should not want to live in a world in which Jeremy Bentham’s or even John Stuart Mill’s utilitarianism reigned supreme to the exclusion of all Kantian and neo-Kantian approaches, nor would I want to live in an entirely Kantian world in which categorical imperatives were always slavishly followed. Bentham serves as a check on Kant and vice versa, just as religion serves as a check on science, science on religion, socialism on capitalism, capitalism on socialism. Rights serve as a check on democracy, democracy as a check on rights, jurisprudence serves as a check on realpolitik, and realpolitik as a check on jurisprudence.

Our constitutional system of checks and balances has an analogue in the marketplace of ideas. We have experienced the disasters produced by singular truths, whether religious, political, ideological, or economic. Those who believe they have discovered the ultimate truth tend to be less tolerant of dissent. As Thomas Hobbes put it, “nothing ought to be regarded but the truth,” and it “belongeth therefore to [the sovereign] to be judge” as to that truth.9 To put it more colloquially, who needs differing—false—views when you have the one true view? Experience demonstrates we all do! The physicist Richard Feynman understood the lessons of human experience as well as the limitations of human knowledge far better than the philosopher Hobbes when he emphasized the basic freedom to doubt, a freedom that was born out of the “struggle against authority in the early days of science.”10 That struggle persists, as we seek to construct a new jurisprudence to regulate an old phenomenon that has operated for centuries with few constraints.

The first step in constructing a jurisprudence to govern the use of a given governmental activity, such as preemptive or preventive self-defense, is to acknowledge the existence and possible legitimacy of that activity.

So long as nations are threatened by other nations or terrorist groups, preemptive or preventive military action will remain an option and will on occasion be employed. When international organizations are incapable of, or refuse to, intervene in situations where intervention is deemed necessary, nations will act unilaterally or with selected allies. That is the reality, and no jurisprudence will ever change that because a nation’s survival is not, and never will be, purely a matter of law. No nation will ever commit “politicide” simply to avoid violating unrealistic and hypocritical laws. If a jurisprudence has any prospect of influencing the behavior of nations, it must reflect the reality that all nations will place their own survival and that of their citizens above any obligations to comply with international law, especially if other nations routinely ignore such law, treating it as merely hortatory or hypocritical. It is not particularly useful therefore to debate preemption or prevention as a yes or no, black or white, legal or illegal policy. Far more useful is the consideration of which factors should inform any decision on whether to act in anticipation of inchoate dangers and whether, and under what circumstances, such actions may properly include, for example, full-scale preemptive war of the kind initiated by the United States against Iraq in 2003, the kind of targeted killings of ticking bomb terrorists that Israel and the United States have employed, the multifaceted in-and-out type of strike currently being considered against Iranian nuclear facilities, or any other of the controversial mechanisms currently in use or contemplated for the future.

The Limited but Important Role of Jurisprudence in International Relations

Before we consider the factors that should become part of any jurisprudence of international preemption or prevention, it is important to answer the question earlier posed: In light of the reality that no nation will place its obligations to comply with international law above its obligations to protect its citizens and assure its own survival, is there any realistic prospect that a jurisprudence can be constructed that can actually influence the actions of nations that believe they are under the gun?

My answer is a “qualified yes,” with equal emphasis on both words. I agree generally with the pithy assessment of Professor Louis Henkin: “It is probably the case that almost all nations observe almost all principles of international law and almost all of their obligations almost all of the time.”11 (I would disagree only with his inclusion of “almost all nations,” since there are a considerable number of nations that simply disregard international law nearly all the time. I prefer to state the proposition in its more negative form: Almost no nations observe all the principles and all their obligations all the time. Our points are similar but differ in nuance.)

The likelihood that a nation will comply with international law increases as the law comes closer to reflecting reasonable reality. The law should not merely follow what nations would actually do in the absence of any legal constraints. Such a law would not influence behavior; it would merely mirror and legitimize existing behavior, whether it was reasonable or not. The Talmud says, “See how people act, and that is the law.”12 But such a law would merely be descriptive rather than prescriptive. The goal of international law should be to influence the behavior of nations at least near the margins, to nudge them in the right direction in close cases, to become one of the primary considerations in the decision on whether to act in certain ways under pressure. That is a modest but important goal. It is modest because it recognizes that law alone will never become the only factor in a nation’s decision on when and how to defend itself in the face of a serious threat or in anticipation of a serious harm. It is important because if international law is to be taken seriously in any context, it must have some influence in every context, even the most extreme. It should never be ignored completely, as it often is today because of its merely hortatory and thus unrealistic nature.

An analogy to the law of domestic self-defense might prove instructive. Justice Holmes wisely observed that “detached reflection cannot be demanded in the presence of an uplifted knife.”13 In other words, when an assailant is threatening to kill an innocent person, that person will not necessarily focus on the intricacies of the law of self-defense in deciding how to respond. He will act immediately to save his own life. If the law required the person to try to reason with his assailant before drawing his gun and killing him, even if the delay caused by this requirement would increase his own chances of being killed, that law would be ignored because it does not reflect reality in imposing an unreasonable risk on the potential victim of an unlawful assault. But it does not follow from this extreme example that all laws regulating and even restricting the use of self-defense will always be ignored. Consider, for example, the current debate, stimulated by the National Rifle Association, over whether a person who is being threatened (say, by a slow man with a knife) should be obliged to retreat if he can do so with safety or is entitled to stand his ground and kill his assailant. The traditional rule has been that a threatened person need not retreat from his own home (presumably because of the protection afforded by familiar surroundings), but that if he can safely retreat in a public place (say, by getting into his car and driving away from an assailant on foot), he must do so before resorting to lethal force. The NRA is lobbying to allow anyone threatened to stand his ground and kill even on a public street and even if he can do so with safety.14 “Law-abiding people should not be told that if they are attacked, they should turn around and run,” an NRA lobbyist told Florida legislators, who approved a bill that would eliminate the duty to retreat. “This bill gives back rights that have been eroded and taken away by a judicial system that at times appears to give preferential treatment to criminals.”15

The object of the law of self-defense is to influence conduct at the margins, to nudge individuals who are under immediate threat to act reasonably in close cases. States that insist on the obligation to retreat when retreat would not raise the risk of death do so for a reason: They wish to reduce the frequencies of deaths in such situations because they value life—even the life of the guilty assailant—over values such as machismo and even dignity. It may well be demeaning for a person to have to run away from an assault rather than stand his ground and confront his assailant by force, but being demeaned is less bad than killing if there is a realistic option. A person is allowed to take the law into his own hands only if there is no other alternative consistent with society’s preference for the life of the innocent victim over the life of the guilty assailant, only if he finds himself essentially in “a state of nature,” with no realistic recourse to the police or to self-help short of killing. If there is an alternative—even if it involves running away in a demeaning manner—that is to be preferred. At least that is the judgment of those who favor laws requiring retreat. Those who oppose such laws believe either that as an empirical matter more lives (or more innocent lives) will be saved by not requiring retreat or that as a normative matter it is wrong to require someone to retreat from an unlawful assailant. Both will agree, however, with the point most relevant to this discussion—namely, that even in the context of an uplifted knife the law is capable of influencing behavior at the margins, that at least some people may be influenced in some of their actions some of the time by whether the law does or does not require retreat.

If individuals can sometimes be influenced even in the presence of an uplifted knife, then it seems likely that nations, whose actions tend to be more deliberative, more calculated, and more communal, can also be influenced in situations of danger, even imminent danger, if laws that seek to influence them do not ask too much of them and are realistic and reasonable.

The analogy between the domestic law of individual self-defense and the international law of national self-defense is of course incomplete because there are so many crucial differences in context. One of the most challenging tasks in the construction of a jurisprudence for a discrete subject area, such as preemption and prevention, is to integrate it into the existing general jurisprudence. Analogy is a powerful tool in accomplishing such integration. The key to employing analogy fruitfully is to understand both the similarities and the differences between the areas to be analogized. It is to this question that we now turn, comparing and contrasting the law (to the extent it can be characterized as law) of anticipatory self-defense in the international sphere to the (fairly well-established) law in the domestic context.

The Analogy between International Self-defense and Domestic Self-defense

Just as there are differences between individual “retail” crime and group “wholesale” terrorism, so too there are differences between domestic and international law with regard to preemption and prevention. There seems to be an implicit recognition that the rules authorizing preventive self-defense among nations in the international arena is, and should be, different from the rules governing self-defense among individuals within a domestic legal system. International law recognizes anticipatory military actions under narrow but meaningful circumstances, whereas domestic law generally forbids any anticipatory self-defense, even if death is highly unlikely. For example, if a nation declares war on its enemy and masses troops at its border in anticipation of an imminent attack, the enemy has the right to strike first, as Israel did in 1967. Even reasonable advocates of the most restrictive views of anticipatory national self-defense would agree with Professor Myres McDougal’s reading of the United Nations Charter:

[U]nder the hard conditions of the contemporary technology of destruction, which makes possible the complete obliteration of states with still incredible speed from still incredible distances, the principle of effectiveness, requiring that agreements be interpreted in accordance with the major purposes and demand projected by the parties, could scarcely be served by requiring states confronted with necessity for defense to assume the posture of “sitting ducks.” Any such interpretation could only make a mockery, both in its acceptability to states and in its potential application, of the Charter’s major purpose of minimizing unauthorized coercion and violence across state lines.16

On the other hand, if a Mafia capo puts out a contract on an enemy and hires a hit man to kill him, the enemy may not lawfully kill the hit man unless he is in the process of actually carrying out the contract. The difference is that in the Mafia case, the potential victim is required by the law to call the police, whose job it is to protect him and arrest his prospective killer. In the context of war, the potential victim state is also supposed to call upon the UN, and especially the Security Council, to protect it from attack. That at least is the theory. But the reality is that in many situations there is no police force capable of preventing the attack upon the victim nation. Self-help is often the only remedy, and it must include a reasonable opportunity to strike before being struck.17 An analogy in the domestic context may be helpful. A battered woman is not authorized to engage in anticipatory self-defense by killing her batterer while he is asleep. She is supposed to leave and call the police. But until recently (and even now in some parts of the world) a battered woman could not realistically count on the police to prevent a recurrence of the battery or even an escalation that will place her life in jeopardy. Some jurors therefore have ruled in favor of battered women who took the law into their own hands and killed their sleeping batterers.18

The United Nations’ Charter provides little guidance to the circumstances, if any, under which preemptive military action is lawful. Article 51 confirms “the inherent right of individual or collective self-defense if an armed attack occurs against a member.” The use of the word “occurs” suggests that preventive self-defense against an imminent and certain attack is never lawful and that a member state must wait until an armed attack is actually initiated by an enemy. If this is the intended meaning of Article 51, then it is not only unrealistic, but also morally unacceptable, especially in an age of weapons of mass destruction, when a first strike can be catastrophic and make reactive self-defense more difficult or even impossible. Not surprisingly, Article 51, in its most restrictive interpretation, has been widely ignored. It is not law at all. It is merely hortatory, and it is bad hortatory to boot!

Under the literal meaning of Article 51, Israel’s preemptive attack against the Egyptian and Syrian air forces in June 1967 would have been unlawful since Israel was not defending itself against an armed attack that had already occurred. The closing of an international waterway to Israeli shipping (which is a casus beli under customary international law but is not an “armed attack” under Article 51) would not have been enough. Nor would have the expulsion of UN peacekeepers, the massing of Egyptian troops along the Israeli border, or the specific threats of genocidal war that required Israel to call up its civilian reserves. An actual armed attack—an illegal first strike by Egypt that could have put Israel at a significant military disadvantage—was a necessary prerequisite for Israeli military action.

Israel did not wait for an actual armed attack to strike. It acted preemptively and was not condemned by the Security Council.19 This inaction in the face of a preemptive attack may be seen as a confirmation of the lawfulness of the Israeli action, though it is always speculative to ascribe too much meaning to institutional inaction, especially by the Security Council with the potential veto power of all its permanent members.

One reason why Israel’s preemptive attack may have escaped condemnation is that it may fall within the narrow criteria that had been articulated in the famous Carolina case in which U.S. Secretary of State Daniel Webster considered the legal status of a British attack on a ship, then moored in the United States, that was being prepared for use against the British forces in Canada. Webster justified the use of cross-border anticipatory force only when the “necessity of . . . self-defense is instant, overwhelming and leaving no choice of means, and no moment of deliberation.”20 This sounds very much like the domestic law of self-defense, but it has been interpreted more broadly because of the reality that most nations live in a state of nature when it comes to defending themselves from potential aggression. Though there is nearly always time for a “moment of deliberation,” Israel was forced by the Egyptian actions to preempt what it reasonably believed, and what Egypt wanted it to believe, was an imminent and potentially catastrophic attack.

In December 2004 a report was issued by the United Nation’s High-level Panel on Threats, Challenges and Change. This long-awaited and highly publicized report, by a group of distinguished international lawyers and diplomats, recommended significant changes in the Security Council’s approach to the prevention of nuclear terrorism. It acknowledged that despite the “restrictive” language of Article 51, “a threatened state, according to long established international law, can take military action as long as the threatened attack is imminent, no other means would deflect it and the action is proportionate.”21 The former foreign minister of Australia Gareth Evans, who served on the panel that issued the report, argued against a restrictive, literal interpretation of the narrow words of Article 51:

It has long been accepted, both as a matter of customary international law predating Article 51 and international practice since, that notwithstanding the language of the article referring only to the right arising “if an armed attack occurs,” the right of self-defence extends beyond an actual attack to an imminently threatened one. Provided there is credible evidence of such an imminent threat, and the threatened state has no obvious alternative recourse available, there is no problem—and never has been—with that state, without first seeking Security Council approval, using military force “preemptively.” If an army is mobilising, its capability to cause damage clear and its hostile intentions unequivocal, nobody has ever seriously suggested that you have to wait to be fired upon. In this sense, what has been described generically as “anticipatory self-defence” has always been legal.22

According to this view, Israel’s preemptive attack of 1967 was entirely legal, as would have been an Israeli preemptive attack in the hours before the Yom Kippur War. The “problem,” according to the report, “arises where the threat in question is not imminent but still claimed to be real: for example, the acquisition, with allegedly hostile intent, of nuclear weapons-making capacity”: the Iraqi situation in 1981 or the current Iranian and North Korean situation. Evans elaborated on this issue:

The problem arises with another kind of anticipatory self-defence: when the threat of attack is claimed to be real, but there is no credible reason to believe it is imminent, and where—as linguistic purists insist—the issue accordingly is not preemption but prevention. (The English language seems to be unique in having two words here—“preemption” to describe responses to imminent threats, and “prevention” for non-imminent ones: that luxury, however, cherished though it may be by policy aficionados who happen to be native English speakers, seems to have done far more to confuse than clarify the debate for everyone else, who tend to use the words, if at all, interchangeably.) The classic non-imminent threat situation is early stage acquisition of weapons of mass destruction by a state presumed to be hostile—the case that was made against Iraq by Israel in justifying its strike on the half-built Osirak reactor in 1981. . . .23

As we have seen, the Security Council condemned Israel for its preemptive attack against the Iraqi nuclear reactor in 1981. The condemnation was unanimous, with even the United States joining. This would seem to suggest that all preventive attacks against nonimminent threats, even of mass destruction, are unlawful. Yet the United States threatened to attack the Soviet missiles that had been placed in Cuba in 1962 and did attack Iraq in 2003, at least in part to prevent the possible use of alleged weapons of mass destruction in the uncertain future. Secretary-general Kofi Annan declared the American attack “illegal” and in violation of the UN Charter: “[F]rom our point of view and from the Charter point of view it was illegal.”24 He did not issue that declaration until eighteen months after the attack, and the United States rejected his conclusion.

The United States has changed its view of the legality and propriety of the Israeli attack on the Iraqi nuclear reactor in the years following the attack. In December 1991 Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney gave the Israeli general who had organized the attack on Osirak a satellite photograph of the destroyed reactor with the following inscription: “With thanks and appreciation for the outstanding job . . . on the Iraqi nuclear program in 1981, which made our job much easier in Desert Storm.”25

Although one of the chief authors of the UN report cited the Israeli attack on the Osirak reactor as an example of a “classic non-imminent threat” by a hostile state, he would still deem such an attack unlawful under the criteria actually promulgated by the UN report. The same would be the case if Israel—or the United States—were to attack Iranian nuclear facilities, even as a last resort. Such preventive—as distinguished from preemptive, attacks would still be unlawful because even if the threat were certain and catastrophic, they were not imminent, and because they were not imminent, they could not lawfully be done unilaterally, without prior approval of the Security Council. This is how the report frames the question:

Can a State, without going to the Security Council, claim in these circumstances the right to act, in anticipatory self-defence, not just pre-emptively (against an imminent or proximate threat) but preventively (against a non-imminent or non-proximate one)? Those who say “yes” argue that the potential harm from some threats (e.g., terrorists armed with a nuclear weapon) is so great that one simply cannot risk waiting until they become imminent, and that less harm may be done (e.g., avoiding a nuclear exchange or radioactive fallout from a reactor destruction) by acting earlier.26

The answer provided by the UN report is clear, if not entirely persuasive in all circumstances: “The short answer is that if there are good arguments for preventive military action, with good evidence to support them, they should be put to the Security Council, which can authorize such action if it chooses to. If it does not so choose, there will be, by definition, time to pursue other strategies, including persuasion, negotiation, deterrence and containment—and to visit again the military option.”27

The report does not suggest what a country should do if all non-military options fail and the Security Council refuses to authorize military action. Nor does it tell a country what to do if the threat itself is not imminent but the opportunity to prevent the threat will soon pass, as was claimed by Israel with regard to the soon-to-be-hot Iraqi nuclear reactor. The implication is that it should do nothing, at least not without Security Council authorization, until and unless it is attacked first or an attack becomes imminent.

The reason given for this answer is in the form of a “slippery slope” argument: “For those impatient with such a response, the answer must be that, in a world full of perceived potential threats, the risk to the global order and the norm of non-intervention on which it continues to be based is simply too great for the legality of unilateral preventive action, as distinct from collectively endorsed action, to be accepted. Allowing one to act is to allow all.”28

Once again Evans elaborates:

The problem here is not with the principle of military action against non-imminent threats as such. It is perfectly possible to imagine real threats which are non-imminent—including the nightmare scenario combining rogue states, WMD and terrorists. The problem boils down to whether or not there is credible evidence of the reality of the threat in question (taking into account, as always, both capability and specific intent); whether the military attack response is the only reasonable one in all the circumstances; and—crucially—who makes the decision. The question is not whether preventive military action can ever be taken: it is entirely within the scope of the Security Council’s powers under Chapter VII to authorise force if it is satisfied a case has been made (and the Council and others these days are quite properly giving increased attention, in relation to both WMD proliferation and terrorism, to circumstances in which such cases might be made). The question is whether military action in response to non-imminent threats can ever be taken unilaterally.29

The “biggest problem” with unilateral anticipatory self-defense in situations in which the threat is not imminent is that “it utterly fails to acknowledge that what is sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander, legitimising the prospect of preventive strikes in any number of volatile regions, starting with the Middle East, South and East Asia. To undermine so comprehensively the norm of non-intervention on which any system of global order must be painstakingly built is to invite a slide into anarchy. We would be living in a world where the unilateral use of force would be the rule, not the exception.”30

The point is an important one that raises questions about the possibility of constructing a singular jurisprudence capable of governing all situations. We should heed the wise counsel of Giordano Bruno, a sixteenth-century philosopher, who cautioned that there is “no one law governing all things,”31 certainly no one moral or jurisprudential law or even principle. There may be very general guidelines for conduct, such as those reflected in the story of the skeptic who asked Rabbi Hillel, who lived just before Jesus, to summarize the Torah while standing on one foot. Hillel provided the following translation: “What is hateful to you, do not to your neighbor. That is the whole Torah, while the rest is the commentary thereof . . .”32 Nor should we simply accept self-serving conduct as an alternative to jurisprudence. A rule that authorizes any country to act unilaterally in cases of nonimminent danger, even nuclear danger, would indeed invite self-serving decisions, if not “anarchy.” But a rule that requires nations to put their own survival in the hands of a potentially hostile international organization will simply not be followed. The concern is not so much with the rule in theory as with the failure to take into account the reality of how the Security Council is constituted and how it makes its decisions. The problem is more with the mechanism of applying and enforcing the jurisprudence than with the content of the jurisprudence itself.

The premise underlying the report’s argument—that any government in reasonable fear of a relatively certain but not imminent nuclear attack can rely on the Security Council to prevent a catastrophe—is demonstrably false. That premise is that the members of the Security Council, particularly its members with the power to veto, would vote in accord with the principles governing preventive and preemptive self-defense. These principles, this attempt to articulate a jurisprudence, are set out in the report as follows:

In considering whether to authorize or endorse the use of military force, the Security Council should always address—whatever other considerations it may take into account—at least the following five basic criteria of legitimacy:

a) Seriousness of threat. Is the threatened harm to State or human security of a kind, and sufficiently clear and serious, to justify prima facie the use of military force? In the case of internal threats, does it involve genocide and other large-scale killing, ethnic cleansing or serious violations of international humanitarian law, actual or imminently apprehended?

b) Proper purpose. Is it clear that the primary purpose of the proposed military action is to halt or avert the threat in question, whatever other purposes or motives may be involved?

c) Last resort. Has every non-military option for meeting the threat in question been explored, with reasonable grounds for believing that other measures will not succeed?

d) Proportional means. Are the scale, duration and intensity of the proposed military action the minimum necessary to meet the threat in question?

e) Balance of consequences. Is there a reasonable chance of the military action being successful in meeting the threat in question, with the consequences of action not likely to be worse than the consequences of inaction?33

Whatever one may think of these principles in the abstract—and they are quite abstract and subject to varying interpretations in concrete cases—there is absolutely no evidence to support the premise that Security Council members vote in accord with any principle other than that of self-serving advantage and realpolitik bias. The historical evidence is all to the effect that the Security Council is not a principled institution, with constituent members who vote on the basis of neutral or objective criteria of justice or law. Professor Michael Glennon has realistically described existing international law: “[T]here is, today, no coherent international law concerning intervention by states. . . . The received rules of international law neither describe accurately what nations do, nor predict reliably what they will do, nor describe intelligently what they should do when considering intervention.”34

The decisions of the Security Council are in fact predictable, but not on the basis of any legal or moral criteria. Instead they are predictable on the basis of whose ox is being gored and which entity is accused of goring it. There is an old story about a young lawyer who finds two cases with exactly the same facts that were decided differently. He asks his senior partner how this disparity in results can be explained in light of the facts. “You’ve ignored the most important facts,” the more experienced lawyer quips. “The names of the parties.” Whether or not this is sometimes an exception to the rule of equal justice before courts of law—and it surely is of at least some35—it is the rule in the Security Council. The names of the countries matter far more than their actions. Votes are traded, extorted, bought, and sold. That is the reality, as anyone who has studied the institution in operation will attest.

Despite having been a member of the United Nations since 1949, Israel has never been given the opportunity to sit on the Security Council.36 Nor can it obtain protection from that body because of who does serve on it.37 There was no realistic possibility that Israel could have ended the Iraqi nuclear program in 1981 through the Security Council. Nor could it have prevented it through diplomacy, which it tried for months without any prospect of success. The French, who were the primary suppliers of nuclear material to Iraq, simply refused to take any action that would have eliminated the dangers to Israel. Accordingly, Israel had only two options: allowing the Iraqis to develop an offensive nuclear capacity or destroying it unilaterally when they did. It made the right choice, the choice any other nation facing such options would have made. I am certain that Gareth Evans, when he was foreign minister of Australia, would have made the same choice in the absence of realistic alternatives. Indeed, Prime Minister John Howard of Australia told me during a meeting in his office in the spring of 2004 that if his nation could have prevented the devastating terrorist attack on Australian tourists in Bali in 2002, he would have authorized any reasonable military action, even if it had had to be taken unilaterally. He has announced that he would support launching preemptive military strikes against terrorists based in neighboring countries if they posed a threat to Australia, saying that “any Australian prime minister” would do the same. He has also called for a change in the UN Charter to allow a country to launch a preemptive strike against terrorists in other countries.38

The UN report fails to address the situation confronting a democracy with a just claim that is unable to secure protection from the Security Council and that reasonably concludes that failing to act unilaterally will pose existential dangers to its citizens. The report’s deliberate refusal to consider this pressing issue relegates its conclusions to the realm of academic debate—and not very realistic academic debate at that. It also reveals an unwillingness by the United Nations to face up to its own shortcomings and failures. Perhaps the best evidence of the current inability of the UN to deal with dangers that may require preventive intervention lies in the tragic history of its impotence—as well as that of the rest of the world—in the face of humanitarian threats to millions of innocent people, especially in third world countries.

The Analogy between Humanitarian Preemption and Anticipatory Self-defense

We have seen that there are both similarities and differences between anticipatory self-defense in the international and domestic contexts. The most significant difference is the absence of an objective and effective mechanism for implementing any fair jurisprudence. The absence of a jurismechanism necessarily influences the content of a jurisprudence, since no nation can fairly be asked to put its survival, or the lives of its citizens, in the hands of an institution that discriminates against it. We now move to the analogy between humanitarian intervention and anticipatory self-defense. Here too we shall see similarities and differences.

One of the most complex issues faced by a world power such as the United States is whether and when to intervene militarily to protect the lives of strangers, who live in faraway places and are being threatened by their own governments. Genocides based on ethnicity, religion, tribalism, and other factors have been all too common throughout history. In the twentieth century alone, genocide was committed against the Jews, Roma, Armenians, Cambodians, Sudanese, Rwandans, Bosnians, and Bangladeshis. All these could have been prevented, or at least reduced in scope, by preventive military intervention or other measures. Yet the world stood by silently and impotently as millions of people—children, the elderly, women, and men—were slaughtered. One important justification for the creation of the United Nations—and more recently of the International Criminal Court—was to prevent such genocides. But waiting for UN action has been a prescription for disaster. Sometimes the only effective preventive action that can be taken must be taken by individual world powers acting alone or acting in concert outside the official mechanisms of the UN.

What should the criteria be for such unilateral or multilateral “interference” with the “sovereignty” of a nation that is killing its own people? Recently much attention has been devoted to trying to answer this daunting question. The considerations are somewhat similar to those that should govern anticipatory self-defense, though they sometimes differ, because the self-interest of the intervening state is not as directly involved.

Many of those who are most adamantly opposed to military preemption or prevention based on anticipatory self-defense strongly favor humanitarian military preemption or prevention based on the need to defend others. The opposite is also true: Many who favor anticipatory self-defense oppose anticipatory defense of others. The issue has taken on a somewhat ideological or political coloration. Self-defense is seen as hawkish or conservative, while defense of others is seen as dovish or liberal.39

Samantha Power has summarized the dismal history, with a particular focus on the United States:

[T]he United States has consistently refused to take risks in order to suppress genocide. The United States is not alone. The states bordering genocidal societies and the European powers have looked away as well. Despite broad public consensus that genocide should “never again” be allowed, and a good deal of triumphalism about the ascent of liberal values, the last decade of the twentieth century was one of the most deadly in the grimmest century on record. Rwandan Hutus in 1994 could freely, joyfully, and systematically slaughter 8,000 Tutsi a day for 100 days without any foreign interference. Genocide occurred after the Cold War; after the growth of human rights groups; after the advent of technology that allowed for instant communication; after the erection of the Holocaust Museum on the Mall in Washington, D.C. . . .

What is most shocking is that U.S. policymakers did almost nothing to deter the crime. Because America’s “vital national interests” were not considered imperiled by mere genocide, senior U.S. officials did not give genocide the moral attention it warranted. Instead of undertaking steps along a continuum—from condemning the perpetrators or cutting off U.S. aid to bombing or rallying a multinational invasion force—U.S. officials tended to trust in negotiation, cling to diplomatic niceties and “neutrality,” and ship humanitarian aid. . . .

Simply put, American leaders did not act because they did not want to. They believed that genocide was wrong, but they were not prepared to invest the military, financial, diplomatic, or domestic political capital needed to stop it. The U.S. policies [were] not the accidental products of neglect. They were concrete choices made by this country’s most influential decision-makers after unspoken and explicit weighting of costs and benefits.40

The issue of humanitarian intervention is complicated by many factors, among them the reality that a certain threshold of killings must be first reached before a conflict is deemed to be producing “genocide.” In that respect humanitarian intervention is rarely pure preemption or prevention. The goal is to prevent further killings, but that should make intervention easier to justify since there is already a predicate of past crimes. Another complicating factor, one that cuts against intervention, is that the conflict is often internal, and the legal basis for intervening in internal disputes is more questionable than in international disputes. But analogies to domestic law do provide some basis for some intervention, and developing legal doctrines are strengthening it.

Domestic criminal law authorizes the use of force, even lethal force both for defense of self and for the defense of others. International law is less clear—at least with regard to the unilateral use of force. The United Nations claims a monopoly on the use of military force to prevent humanitarian disasters, such as genocide. In theory, there is no good reason why the UN could not act collectively to prevent such genocides as those committed in Rwanda and Darfur. But the UN has failed miserably in practice, and so have most world powers. A nation will more readily act preemptively or preventively to protect its own citizens and its own interests than to protect the citizens of other nations or to defend abstract principles of humanitarianism. This is especially so when the contemplated action places the lives of its own military personnel at risk. A president who sends American troops into harm’s way had better be able to justify his decision by reference to some principle that is acceptable to the public.41 In a democracy, military actions must be approved—if not initially, then certainly over time—by the citizenry. Self-interest is a primary motivator, though altruism can also stimulate action. Sometimes, of course, altruism can serve the national interests of a world power, as the United States learned following the tragic tsunami in December 2004. Aid to Muslim areas became part of our war against terrorism.42 Moreover, preventive self-defense can be broadly defined so as to include military interventions that seem at best quite distant from conventional self-defense. The various domino theories that have been cited to justify wars far from home illustrate this phenomenon. Thus the difference between a preventive war of self-defense and a humanitarian war in defense of others may often be a matter of degree or of articulated justification. Indeed, the invasion of Iraq was justified both on grounds of self-defense against weapons of mass destruction and on grounds of humanitarian intervention to prevent a tyrant from continuing to kill and torture his own people. Neither justification turned out to be compelling, since no WMDs were found and the invasion almost certainly caused more deaths among Iraqi civilians than Saddam Hussein was likely to have caused had he remained in power.

As we shall see in the pages to come, a new doctrine called “the responsibility to protect” is in the process of being developed, particularly in the context of humanitarian intervention. This doctrine challenges traditional notions of state sovereignty in situations in which a state is incapable of or unwilling to protect its own citizens from such humanitarian threats as genocide, famine, and ethnic cleansing. It has also been suggested that the jurisprudence that underlies this doctrine may provide analogous support for a doctrine of anticipatory self-defense, particularly in the context of weapons of mass destruction.

An article in Foreign Affairs by two distinguished international scholars, Lee Feinstein and Ann-Marie Slaughter, suggests a framework for analyzing this issue as well as other preventive actions. It begins by critically assessing the traditional concept of state sovereignty in the context of humanitarian intervention:

In the name of protecting state sovereignty, international law traditionally prohibited states from intervening in one another’s affairs, with military force or otherwise. But members of the human rights and humanitarian protection communities came to realize that, in light of the humanitarian catastrophes of the 1990s, from famine to genocide to ethnic cleansing, those principles will not do. The world could no longer sit and wait, reacting only when a crisis caused massive human suffering or spilled across borders. . . . As a result, in late 2001, an international commission of legal practitioners and scholars, responding to a challenge from the United Nations secretary-general, proposed a new doctrine, which they called “The Responsibility to Protect.” This far-reaching principle holds that today UN member states have a responsibility to protect the lives, liberty, and basic human rights of their citizens, and that if they fail or are unable to carry it out, the international community has a responsibility to step in.43

This doctrine, they correctly observe, “took on nothing less than the redefinition of sovereignty itself” and requires “states to intervene in the affairs of other states to avert or stop humanitarian crises.” The criteria or threshold for such preventive intervention will, of course, depend on the nature and degree of harm feared and the nature and degree of intervention required to stop or diminish the harm. But it is difficult to disagree with the concept itself—namely, that claims of sovereignty should not always trump humanitarian concerns when a nation inflicts grievous harm on its own citizens or residents.

The authors then proposed a “corollary principle” in the area of global security or self-defense:

. . . a collective “duty to prevent” nations run by rulers without internal checks on their power from acquiring or using WMD. For many years, a small but determined group of regimes has pursued proliferation in spite of—and, to a certain extent, without breaking—the international rules barring such activity. Some of these nations cooperate with one another, trading missile technology for uranium-enrichment know-how, for example. . . . These regimes can also provide a ready source of weapons and technology to individuals and terrorists. The threat is gravest when the states pursuing WMD are closed societies headed by rulers who menace their own citizens as much as they do their neighbors and potential adversaries. Such threats demand a global response. Like the responsibility to protect, the duty to prevent begins from the premise that the rules now governing the use of force, devised in 1945 and embedded in the UN Charter, are inadequate.44

This principle too challenges conventional notions of sovereignty:

The commission’s effort[s] to redefine basic concepts of sovereignty and international community in the context of humanitarian law are highly relevant to international security, in particular to efforts to counter governments that both possess WMD and systematically abuse their own citizens. . . . We argue, therefore, that a new international obligation arises to address the unique dangers of proliferation that have grown in parallel with the humanitarian catastrophes of the 1990s. The duty to prevent is the responsibility of states to work in concert to prevent governments that lack internal checks on their power from acquiring WMD or the means to deliver them. In cases where such regimes already possess such weapons, the first responsibility is to halt these programs and prevent the regimes from transferring WMD capabilities or actual weapons. The duty to prevent would also apply to states that sponsor terrorism and are seeking to obtain WMD.45

As with regard to humanitarian intervention, so too with regard to preventing the spread of WMDs to nations likely to use them aggressively, the principle itself is not controversial: “The utility of force in dealing with the most serious proliferation dangers is not a controversial proposition.”46 Both the United States and European Union have asserted the power to act preventively against proliferation of WMDs. The controversial aspects of this policy revolve around several practical problems, primary among which is the propriety of a single nation’s acting alone (or with an ersatz “coalition of the willing”) rather than through the United Nations. The authors considered this issue and concluded: “Given the Security Council’s propensity for paralysis, alternative means of enforcement must be considered. The second most legitimate enforcer is the regional organization[s]. . . . It is only after these options are tried in good faith that unilateral action or coalitions of the willing should be considered.”47

This presumption in favor of collective action may seem reasonable when the United States is the nation at risk because we have power and influence, limited as they sometimes are, within the UN and other regional organizations. But it has little practical application to a nation such as Israel, which can never count on UN or regional support and must either go it alone—as it did in its 1981 attack on the Iraqi reactor—or with the support, often covert, of the United States. The United States too may, on occasion, have to go it alone (or relatively alone) when it alone is the target of the WMDs. It is important therefore to consider the appropriate criteria for preventive military self-help against the likely, though not imminent, development and deployment of WMDs. Feinstein and Slaughter suggested the following guidelines:

. . . the resort to force is subject to certain “precautionary principles.” All nonmilitary alternatives that could achieve the same ends must be tried before force may be used, unless they can reasonably be said to be futile. Force must be exerted on the smallest scale, for the shortest time, and at the lowest intensity necessary to achieve its objective; the objective itself must be reasonably attainable when measured against the likelihood of making matters worse. Finally, force should be governed by fundamental principles of the laws of war: it must be a measure of last resort, used in proportion to the harm or the threat of the harm it targets, and with due care to spare civilians.48

These criteria would certainly seem to have justified Israel’s bombing of the Osirak reactor. Indeed, they seem to be based on the specific facts of that case. In less than a quarter of a century, therefore, a preventive military action that was unanimously condemned by the Security Council as in clear violation of the UN Charter and customary international law has become the paradigm for proportional, reasonable, and lawful preventive action.49 It has become part of the emerging jurisprudence of preventive military actions. Whether this jurisprudence would also justify, as “a measure of last resort,” a unilateral or bilateral surgical strike against Iranian nuclear facilities is a more daunting question.

Absolute Prohibitions on Preemptive or Preventive Actions

One substantive choice that must be addressed by any jurisprudence is whether there are any preemptive or preventive actions that should always be prohibited under all circumstances. Again, an analogy might be instructive. In the debate over torture, it has been plausibly argued that there should be no substantive jurisprudence of torture and no mechanism for ever authorizing it, even to gather intelligence believed necessary to prevent an imminent terrorist attack. Instead, a simple rule—namely, that all forms of torture must fall into one of those categories of conduct absolutely prohibited by moral principles and not subject to cost-benefit analysis—should be universally recognized. That would be the strictly Kantian position, as contrasted with the Benthamite view which justified the torture of convicted criminals to prevent harms worse than torture. (I have participated in this debate, and my views on it can be easily found.)50 In addition to torture, there are other actions widely believed to be categorically unacceptable—for example, the deliberate targeting of innocent people. It is very likely that the killing of innocent people could be an effective means—perhaps even the most effective means—of preventing or deterring suicide terrorists who do not care about their own lives but might well be influenced by the threat of having loved ones killed. A former high-ranking government official told me that he heard the following account (which he could not independently confirm): At about the same time Middle Eastern terrorists were kidnapping American citizens in Lebanon during the 1980s, there was a kidnapping (or an attempted kidnapping) of a Soviet citizen. The KGB responded by murdering all the relatives of the suspected kidnapper. When the word got around that this would be the uniform response to all kidnappings, there were no more attempts to kidnap Soviet citizens. Whether this story is true or apocryphal, it makes the point: A nation that is prepared to use any means to prevent or deter suicide terrorism can be more effective than a nation that must fight “with one hand tied behind its back”51 because of moral or legal constraints. It may well be that a case-utilitarian argument, weighing the cost and benefits of killing relatives in one specific situation, such as when a credible threat to kill one relative of the kidnapper could save the lives of ten kidnap victims, could be made for choosing the lesser of the evils. (If such a threat were deemed permissible, would it then be permissible to carry it out if the first suicide terrorist were not deterred—perhaps because he did not believe that a democracy would carry out such a threat—in order to assure the next terrorist that the threat was real?) It would be far more difficult, however, to justify such an action on a rule-utilitarian basis, weighing the costs and benefits of accepting a general rule permitting the killing of innocent relatives to save the lives of victims. That a democracy should not deliberately kill an innocent person seems to many to be one of those absolutes that should never be violated, regardless of the stakes. Attorney Nathan Lewin, who argued that killing the families of suicide bombers might be a necessary deterrent,52 received harsh criticism for his stance,53 including from me.54 The intentional killing of an entirely innocent person is a line I do not believe a democracy should cross. Dostoyevsky posed the problem in a famous dialogue between Ivan Karamazov and his brother Alyosha in The Brothers Karamazov. Ivan put Alyosha to the test: “[I]magine that you yourself are building the edifice of human destiny with the object of making people happy in the finale, of giving them peace at last, but for that you must inevitably and unavoidably torture just one tiny creature, that same child who was beating her chest with her little fist, and raise your edifice on the foundation of her unrequited tears—would you agree to be the architect on such conditions? Tell me the truth.” Alyosha replied without hesitation: “No, I would not agree.”55 The problem can be posed even more concretely in the context of the Holocaust. What if the Jewish underground had credibly believed that if by blowing up German kindergartens in Berlin, they could force the closure of the death camps—that the killing of a hundred innocent German children would save the lives of one million innocent Jewish children and adults? Would this be a morally permissible choice of evils? Kant would say no. Bentham would say yes. Alyosha would say no. Ivan would say yes. Those Jewish families that suffocated their own crying babies to prevent the Nazis from finding the rest of them said yes, and the rabbis agreed. The Catholic Church says no. This horrible no-win dilemma will never be resolved to the satisfaction of all moral people, but most will certainly agree that the willful killing of innocent people crosses a line that should be crossed, if ever, only in the most extreme situations. There are some, however, who argue that there is really no moral or practical difference between an action that willfully targets innocent people intending to kill them and an action that targets only the guilty but with full knowledge that innocent people will be killed “collaterally.” The implications of this argument cuts both ways: For some the lack of a meaningful difference between willful and unintended killing of innocents cuts against the latter, while for others it cuts in favor of the former. The reality of course is that every society engages in self-protective actions against the guilty with full knowledge that some innocents may be killed in the process.

Although some have argued that preventive war, as distinguished from preemptive attacks, must be included among those actions that should always be categorically prohibited, that does not seem a plausible conclusion in an age of weapons of mass destruction, except if one engages in the word game of defining “preemptive attack” so broadly as to include at least some preventive wars. Certainly preemption is widely, if not universally, regarded as a proper option for a nation operating under the rule of law, at least in some circumstances—for example, when a threat is catastrophic and relatively certain, though nonimminent, and when the window of opportunity for effective prevention is quickly closing. Accordingly, we should now move to the next stage in constructing the jurisprudence—namely, to articulate principles, standards, and criteria for when preemptive action is warranted, as well as when and whether preventive war is justified.

Factors to Be Considered in Decisions to Engage in Preemptive and Preventive Military Action

If there are a wide array of preemptive and preventive actions that should be neither always prohibited nor always permitted, then it is essential that the criteria governing such actions be articulated and, to the extent possible, agreed to by the international community.

Primary among the factors that should be considered are the severity, certainty, and imminence of the threat, on the one hand, and the nature, scope, and duration of the contemplated preemptive actions, on the other. There is a considerable difference between a one-shot, decisive military strike, such as Israel’s destruction of Iraq’s nuclear reactor, and a full-blown military invasion followed by a lengthy occupation, such as the current situation in Iraq. Had the American military succeeded in its attempt to kill Saddam Hussein on the eve of the invasion, and had the subsequent invasion been deemed unnecessary, many people would have a different assessment of the propriety of such a preemptive strike. Even if the invasion had occurred, but without the need for a long-term occupation, there might be a different view.

Although the array of potential anticipatory military actions cannot be neatly lined up in a single continuum, it is possible to set them out in some orderly way, beginning with the least intrusive and moving to the most intrusive. The least intrusive end of any such continuum might consist of military or quasi-military actions that do not actually intrude physically into the territory of the enemy. These might include blockades and quarantines designed to prevent dangerous weapons or combatants from reaching the enemy. It might include security fences and other physical barriers on appropriate borders, as well as the mobilization of troops, no-fly zones, surveillance satellites, intelligence overflights, and spy networks.56

At the other end of the continuum would be full-scale invasions, occupations, destruction of the military capacity and infrastructure of the threatening enemy, and even nuclear attack.

Between these extremes lies a wide range of escalating military actions, including targeted killing of particularly dangerous individuals who qualify as “combatants,” small-scale attacks on terrorist bases or other threatening enclaves, larger attacks against offensive weapons systems, and even larger-scale attacks on an entire air force, navy, or ground troops.

A related continuum would reflect the frequency of the preventive military action. Some require only a single attack, such as that which destroyed the Iraqi nuclear reactor.57 Others require repeated attacks, such as the targeted killings of terrorists and their leaders. Some are episodic; others continuous, such as the building and maintaining of security barriers, checkpoints, and a long-term occupation designed to prevent remilitarization or the organization of terrorist cells.

Other obvious continua would relate to the certainty, severity, and immediacy of the feared attack. A one-dimensional standard of probable cause and imminence is inappropriate to the myriad risks that may be confronted by a democracy reasonably fearing a catastrophic first strike by an enemy. Even if the likelihood of a nuclear attack were statistically low—say, 5 percent—the number of casualties that could be inflicted in the unlikely event of such an attack must be factored into any moral or legal equation.58 A small but significant risk of nonimminent nuclear attack may provide more justification for a preventive military action than would a large risk of an imminent but small-scale attack with conventional weapons. How to assess the appropriateness of preventive action designed to confront an unlikely but cataclysmic possibility is a daunting task. The likelihood of a false positive increases in proportion to the unlikelihood of the predicted event. But the risks involved in a false negative also increase. Much depends on the comparative consequences of false positives and false negatives.

To give an extreme example, if the military is seeking to test soldiers for eligibility to have access to a nuclear trigger, there is no real risk associated with false positives; it really doesn’t matter how many soldiers are disqualified from such access since there is little stigma attached to disqualification and there is a virtually unlimited pool of potentially qualified soldiers. But the risk of false negatives is potentially catastrophic; giving an unstable or paranoid soldier access to a nuclear trigger could endanger millions of lives. It is a no-brainer, therefore, to err on the side of disqualification, all doubts should be resolved against a potential candidate. If there is even a 1 percent chance that a particular soldier might act irresponsibly, he should be assigned to less risky duty in which a mistake would cause little harm. This will result in a very high number of false positives (disqualified soldiers who would actually pose no risk), but it will also result in significantly diminishing the likelihood of false negatives (soldiers deemed qualified who would actually pose a risk). The trade-off is well worth it.

A counterexample was presented by an injunction granted during the 2004 Republican National Convention that prevented protesters from assembling in Central Park in New York City because there was a high probability that such a gathering would harm the grass in the park. Even if it were 95 percent likely that the grass would be damaged, that sort of damage is remediable, whereas the damage done to freedom of protest during a quadrennial presidential convention is irremediable. What Justice Louis D. Brandeis observed three-quarters of a century before the convention is as relevant today as it was then:

[E]ven imminent danger cannot justify resort to prohibition of these functions essential to effective democracy, unless the evil apprehended is relatively serious. Prohibition of free speech and assembly is a measure so stringent that it would be inappropriate as the means for averting a relatively trivial harm to society. A police measure may be unconstitutional merely because the remedy, although effective as means of protection, is unduly harsh or oppressive. Thus, a State might, in the exercise of its police power, make any trespass upon the land of another a crime, regardless of the results or of the intent or purpose of the trespasser. It might, also, punish an attempt, a conspiracy, or an incitement to commit the trespass. But it is hardly conceivable that this Court would hold constitutional a statute which punished as a felony the mere voluntary assembly with a society formed to teach that pedestrians had the moral right to cross unenclosed, unposted, waste lands and to advocate their doing so, even if there was imminent danger that advocacy would lead to a trespass. The fact that speech is likely to result in some violence or in destruction of property is not enough to justify its suppression. There must be the probability of serious injury to the State. Among free men, the deterrents ordinarily to be applied to prevent crime are education and punishment for violations of the law, not abridgment of the rights of free speech and assembly.59

Justice Brandeis’s reasoning is correct for two related reasons: First, the value we (and the First Amendment) place on freedom of speech is so great—especially in the context of prior restraint—that we properly demand that an extraordinary burden be met before the government is empowered to censor, and second, this burden simply cannot be met by invoking remediable risks to property, such as trespassing or damaging the grass. Any contemplated governmental action that restrains the exercise of core democratic liberties, such as freedom of speech or assembly, will rarely be able to satisfy the stringent burden of proving that the evil sought to be prevented is so serious, and so difficult to deter, that the disfavored mechanism of prior restraint is constitutionally permissible. In this area, more than in others, we are willing to tolerate many false negatives (speeches that we mistakenly believe will not cause harm) in order to avoid even a small number of false positives (speeches that we mistakenly believe will cause harm).60

There are, of course, obvious and important differences between the stakes involved in ruining grass in a park and in preemptive or preventive military attacks. There are also differences between full-scale military attacks, on the one hand, and focused preemption, on the other. In deciding whether to authorize the targeted killing of specific terrorists, especially if some “collateral” deaths may result, various factors should be considered. They should be as specific as possible. Some of the factors that should go into a decision to engage in preemptive targeting include the following:

How likely is it that the proposed target is a legitimate

combatant?

A. Has he engaged in terrorism in the past? If so, how often and of what kind?

B. Is he currently involved in planning future terrorism? If so, how imminent? What is his precise role?

C. Will killing him prevent future acts of terrorism? Will it provoke other acts of terrorism?

D. How reliable is the intelligence on which the above assessments are made? Can accurate probability numbers be attached to them? If so, what are the probabilities?

Are there reasonable alternatives to killing him?

A. Can he be arrested or captured?

B. If so, at what risk to arresting soldiers or police officers?

C. Is he likely to submit to arrest or fight to the death?

D. If he does not submit, what is the likely casualty assessment?

E. What would be the political consequences of trying to apprehend him?

F. What would be the consequences of placing him on trial? Would it stimulate hostage-taking or other forms of terrorism?

How certain is it that the terrorist can be preemptively killed

without undue risk to uninvolved others?

A. What is the likelihood that uninvolved enemy others may be killed or seriously injured if action is taken?

B. What is the likelihood that one’s own civilians may be killed or seriously injured if action is not taken?

C. Can these risks to civilians—both enemy and one’s own—be eliminated or reduced by placing the lives of one’s own soldiers at risk?

D. How should a moral society compare the value of its own civilian lives to the value of enemy civilian lives? Of its own conscripted soldiers to enemy civilians? (The American decision to bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki was based explicitly on sacrificing Japanese civilian lives to spare American military lives.)

E. Should the lives of all enemy civilians be valued the same, or should a “continuum of civilianity” (or a continuum of “involvement”) be employed?

F. How reliable will any such continuum be, since it is far more difficult to obtain reliable intelligence about people marginally involved in terrorist activities.

G. Should it matter whether the dangerous actions being undertaken by the target are legal or illegal (under the domestic law of the state in which he is operating, under international law, under the law of the targeting state)?

It would be virtually impossible in the real world to quantify these variables with any degree of accuracy or precision, but it may be valuable nonetheless to assign hypothetical numbers to them for heuristic purposes.

Can a number be attached based on the reliability of intelligence, the likelihood and imminence of the danger, the degree of anticipated harm—e.g., 100 for 100 percent reliability, 100 percent certainty, 100 percent imminence, and 10 or more certain deaths? This number would be reduced when intelligence is less certain, harm is less imminent, and fewer than 10 deaths likely (and raised if the number of likely deaths to be prevented exceeds 10). A minimum total score would be required for lethal action.

Can a number be assigned to the likelihood that the terrorist could be apprehended without killing him or others?

A. Should different numbers be assigned to different categories of potential casualties—e.g., the terrorist, his supporters, police officers or soldiers, uninvolved adult civilians, children?

B. If so, what would these numbers be?

Can a number be assigned to the likelihood that uninvolved persons may be killed or injured if targeted killing is attempted?

A. How many?

B. How uninvolved on a scale of 10 (baby) to 1 (active supporter)?

A maximum total score would preclude action, except in extraordinary situations, such as nuclear terrorism.

Can the likelihood that uninvolved persons may be killed be reduced by reducing the likelihood of killing the targeted terrorist—e.g., smaller bomb, waiting for fewer people nearby?

A. How much of a reduction of collateral damage is acceptable in order to reduce the likelihood of killing the targeted terrorist by how much? This will depend on the number assigned to the danger. The closer one gets to 100, the higher the tolerance for the risks to uninvolved people; the further one gets from 100 and the closer to the minimum for action, the less tolerance for the risks to uninvolved people.

I do not believe that these complex factors can be quantified in real life with the degree of exactitude implied by the assignment of numerical scores.61 But it is a useful heuristic exercise to frame the issues in a quantifiable manner so that rough weights can be assigned to each of them. If the perfect is the enemy of the good, then the exact is the enemy of the approximation, and approximation is often better than mere intuition in weighing choices of evil that involve assessments of risk and probabilistic outcomes.

This sort of exercise can be applied, with relevant adjustments, to other preemptive or preventive mechanisms, such as preventive detention, profiling, and quarantine. It is an important step in formulating a jurisprudence. Another essential step is to consider how to evaluate the costs in differing contexts of the mistakes that will inevitably be made. It is to that step that we now turn.

How to Think about Inevitable Mistakes

When the issue is one-dimensional—a simple prediction whether or not an individual (say, a suspected terrorist) will cause an identified harm (an act of terrorism) within a specified time period (say, a year)—the choices and outcomes can be represented by the following simple matrix: