In August 1972, I wrote an article for the American Bar Association Journal that dealt with the mathematics of prediction and especially the difficulty of accurately predicting relatively rare events without incurring large numbers of false positives. In 1975, I applied my analysis to the use of karyotypes in predicting criminal behavior. I reproduce these articles here (in slightly edited form) because they are relevant to many decisions involving preventive or preemptive governmental actions based on probabilistic predictions.

In the early 1970s—during the heyday of the civil rights and antiwar protests in which many lawyers participated—a committee of the Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar of the American Bar Association recommended that research studies be undertaken “to determine whether character traits can be usefully tested prior to application for admission to the bar. . . .” The following studies were specifically proposed:

A. An interdisciplinary inquiry into what is now being done or projected in other professions or businesses: . . .

(1) To identify those significant elements of character that may predictably give rise to misconduct in violation of professional responsibilities.

(2) To estimate the capacity of those inimical elements to persist despite the maturing process of the individual and the impact of the stabilizing influence of legal education.

B. A “hindsight” study of selected cases of proved dereliction of lawyers to ascertain whether any discoverable predictive information could have been obtained at the law student level by feasible questionnaires or investigation; and if so, what type of inquiry would have been fruitful.

The stated objects of these studies are to determine whether it is “within the present state of the art to devise a test which can be administered to 35,000 or 40,000 22-year-old men and women each year and which will develop any genuinely useful information as to their future conduct and integrity in the practice of law?” Presumably, if an “accurate” predictive test can be devised, it would be used preventively against persons “who in fact have character deficiencies which would deny them admission or which in later years would lead to disciplinary action by the bar.” The report continued: “This in turn would avoid the distressing and sometimes tragic problem of a student becoming aware of this hurdle only after he has invested three or four years of his life in acquiring a legal education.”

The report, which was approved by the council of the Section, did not specify the precise consequences that might follow from predicted “future derilections.” It simpy proposed “leaving to the 50 jurisdictions whatever supplemental inquiry or investigation each might wish to make. . . .” But the concerns that appear to have given rise to the proposal suggest that those who “fail” the predictive test might be weeded out of the “competition for a legal education and ultimate admission to the bar” at an early state or might be “deterred” from entering the competition. The report cited the growing number of applicants for the approximately 36,000 first-year law school seats (80,000 in 1971 and 100,000 in 1972). These figures, according to the report, “have raised increasing concern over the adequacy of present procedures to be sure that those best qualified, both from the standpoint of intellect and motivation and from the standpoint of proper moral character attributes, are the ones who succeed in the competition for a legal education and ultimate admission to the bar.”

The committee acknowledged that it did not know the answer to the question it posed: whether an accurate predictive test can be devised. Pointing to the work that is currently “going on in a variety of fields to come up with some answers to the enigma of predictability of human behavior,” it conceded that it “certainly is not adequately informed as to the nature of success of such efforts.” It expressed the hope, however, that the studies it has proposed “might move [the committee] from sheer guesswork and individual opinion to a more solid footing.”

What Is the Feasibility of Carrying Out These Studies?

The report raises many troubling issues of policy and constitutionality, some of which were discussed in a letter to the President of the American Bar Association from the deans of eight leading law schools. This article will not, however, consider those issues; it will focus instead on the empirical feasibility of carrying out studies of the kind proposed and on the utility of the results that the studies might produce. I respectfully offer some caveats in the hope that they may contribute—albeit in a limited way—to the consideration of the committee’s proposal or other similar proposals.

The report suggested that the “career background of selected offenders” be studied in depth in order to determine “whether there are any patterns or discernible factual matters which might have been discovered at the time of admission to law school and upon which probable future derelictions could have been predicted.”

Hindsight studies of this kind, if properly conducted, are a useful first step in the construction of a prediction index. But no hindsight study of an offender group can by itself produce reliable predictive criteria. Even if a study were to reveal that every past offender possessed certain characteristics in common, it would still not follow that all—or even most—persons who possessed them would become offenders.

This is so for two important reasons. First, these characteristics may not be sufficiently discriminating: that is, they might not only be present in all or most offenders but also in a substantial number of nonoffenders. For example, it may well be true that a large percentage of present heroin addicts previously smoked marijuana; but it is also true that a very small percentage of marijuana smokers become heroin addicts. It may be true that a significant percentage of certain kinds of criminals have XYY chromosomes; but it does not follow that a significant percentage of persons with those chromosomes will become criminals.

The second reason is that the characteristics the study succeeded in isolating might be associated with offenders only in the small past sample and not generally with offenders in other population groups. The sample employed in the hindsight study may have been unique in certain respects. For example, the famous hindsight study of delinquency conducted by Professors Sheldon and Eleanor Glueck was conducted among Boston immigrants of predominantly Irish descent. Considerable doubts have been expressed about its applicability to other populations. The risk of uniqueness is especially great if the original sample is relatively small, as it would necessarily be in the study at issue. Moreover, the characteristics associated with offenders may change over a period of time, especially when attitudes are changing as quickly as they seem to be at present.

Before data derived from a hindsight study can validly be applied to other populations, a prospective validation study should be conducted. The predictive characteristics derived from the hindsight sample should be applied to another population that includes potential offenders and nonoffenders. On the basis of these characteristics, predictions should be made about the future performance of the members of the new group, but these predictions should be kept secret. If they were revealed—to predicted offenders or bar association officials—the validation study would be skewed by the power of self-fulfilling prophecy.

The careers of the new group should then be followed over a number of years—ideally an entire professional career, but at least ten or fifteen years. The actual performance of the group then would have to be matched with the predictions. Only then could it be determined—and even then only tentatively—whether the factor or factors associated with offenders and nonoffenders in the hindsight group were truly characteristic of the general relevant population.

Another but less reliable validation technique would be to apply the predictive characteristics derived from the original sample study to other “past” groups that included both offenders and nonoffenders. If the characteristics succeeded in “postdicting” the past offenders, then there would be some assurance that the original group was not unique.

If the data from a hindsight study were used, without validation, to disqualify law students from further pursuing their careers, then only one aspect of the predictive index would ever be validated. Failures in spotting potential offenders—the false negatives—would be exposed; but few or none of the false positives—those erroneously disqualified—would be exposed, as they would have no opportunity to engage in the predicted conduct. The higher visibility of the failure to spot violators might then incline the testers to expand the category of those to be disqualified.

Unsolvable Dilemma of the Excessive False Positives

Even if these methodological problems could be overcome, there would still be considerable difficulty in usefully applying the resulting predictive index to the population at issue. This can be demonstrated by imagining that a hindsight study was conducted in which the “education and career background” of 1,000 past offenders were studied. Imagine further that the study was enormously successful: that it isolated a number of characteristics that were present in most of the offenders and absent in most of the nonoffenders. For purposes of this analysis, let us postulate that 80 per cent of the offenders possessed one or more of these characteristics and that 80 per cent of the control sample of nonoffenders lacked these characteristics.

It is extremely unlikely in real life that a cluster of characteristics could be discerned to be present in so high a percentage of offenders and absent in so high a percentage of nonoffenders. This is so for the obvious reason, inter alia, that people commit offenses out of a very wide range of motives. In many instances, an offense may be committed by someone with an exemplary past record—recall Dean Landis’s tax conviction; in other instances, persons who seem to have the ideal profile for delinquency in fact never engage in this conduct.

Indeed, Jerome Carlin in his empirical study Lawyers’ Ethics concluded that “situational” factors play a major role in determining whether a lawyer will violate ethical norms. These situational factors—the size and status of his firm, the nature of his clientele, the level of governmental agency with which he deals—would be most difficult to forecast during a student’s first year in law school. Psychologists and other professionals who have tried to construct prediction indexes have been somewhat successful in predicting cognitive performance, such as academic success, but notoriously unsuccessful in predicting such things as “future character derelictions or vulnerability to temptation” (to use the report’s words).

Thus, it is extremely unlikely that characteristics could be discovered that are present in 80 per cent of the offenders and absent in 80 per cent of the nonoffenders. But for purposes of this analysis, it will be assumed that 80 per cent of the past offenders possessed the characteristics and that 80 per cent of the nonoffenders lacked it.

The reason it would be difficult to apply even this highly “accurate” prediction index to the population at issue inheres in the extremely low ratio of potential violators to nonviolators among first-year law students. The population, according to the report, consists of “35,000 or 40,000 22 year-old men and women.” Although precise information is not available as to the number of disciplinary proceedings annually, they are, in the words of an American Bar Foundation report, “certainly small in relation to the number of lawyers.” Despite the “increasing attention to the problem of discipline of lawyers . . . the number of disbarments and forced resignations is probably still less than 150 per year.” This constitutes approximately three quarters of 1 per cent of the yearly new admissions to the Bar. Over the past ten years, there have been fewer than 1,600 lawyers disbarred. This constitutes approximately one half of 1 per cent of the 300,000 currently practicing in the United States. There are no reliable statistics on the number of applicants annually denied admission to the Bar for “character” deficiencies, but the number is probably no more than fifty. This brings the relevant figure to less than 200 per year, or about 1 per cent of the new admissions.

To avoid any charge of understating the case in favor of prediction, the figure will be raised to 5 per cent: it will be assumed that 5 per cent of the 40,000 first-year students to whom the test would be administered will commit conduct resulting in official professional discipline or be denied admission to the Bar. The extreme exaggeration of this figure is illustrated by applying it to the entering class of Harvard Law School: 5 per cent of that class is more than twenty-five students. Surely nowhere near that number will be denied admission or disbarred during their legal careers.

It may be that the committee is seeking to cast its predictive net wider than disbarable conduct and conduct or character deficiencies that would deny the applicant admission to the Bar. It may be seeking to predict all unethical conduct—that is, conduct that now results in reprimand or that goes undetected or unpunished. There is, of course, no reliable estimate of the extent of undetected unethical behavior among lawyers. Mr. Carlin in his book estimates that it may be as high as 22 per cent of the lawyers practicing in New York City, but he also says that “fewer than 2 per cent of lawyers who violate the generally accepted norms of the bar are formally handled by the official disciplinary machinery; only about 0.02 per cent are publicly sanctioned by being disbarred, suspended or censured.” It would be unrealistic in the extreme, therefore, to attempt to predict all violations of ethical norms. The 5 per cent figure certainly covers all violations that are publicly sanctioned by disbarment, suspension or censure. (To the extent that the studies would be seeking to “predict” the existence of those character traits that are currently used to disqualify applicants for admission to the Bar—as distinguished from predicting disbarable conduct itself—then the studies would be attempting a compound prediction, since many of the traits that now disqualify are themselves predictive of ultimate misconduct.)

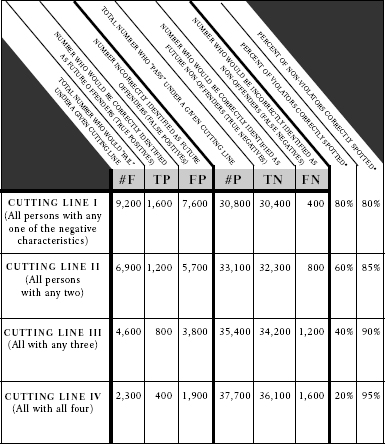

Applying the 80 per cent factors to the population at issue would produce the following results: 80 per cent of the potential offenders would be correctly spotted. This would come to about 1,600 (40,000 × .05 × .80). Eighty per cent of the future nonoffenders would be spotted as well. This would come to 30,400 (40,000 × .95 × .80). But 20 per cent of the potential offenders would be missed: 400 potential offenders would manage to sneak by. More significant, 20 per cent of the nonoffenders would be incorrectly identified as offenders. And here the percentages are extremely misleading. When the figure of 20 per cent is converted into absolute numbers, it turns out that a total of 7,600 students would be identified erroneously as offenders (40,000 × .95 × .20).

Put another way, if a test 80 per cent accurate for offenders and nonoffenders is administered to a group of 40,000 with a “base rate expectancy” of 5 per cent, the result will be 30,800 “passing” scores and 9,200 “failing” scores. The 30,800 passing scores will include 30,400 students who would not commit offenses (these are the true negatives), and 400 who would commit offenses (these are the false negatives). The 9,200 failures will include 1,600 students who would commit offenses (these are the true positives), and 7,600 who would not commit offenses (these are the false positives).

The problem is that it is impossible, under the predictive index being used, to tell the difference between the true positives and the false positives or between the true negatives and false negatives. Either all of the 9,200, or none of them, should be disqualified. If all of the 9,200 were to be prevented or discouraged from continuing their legal education, 1,600 cases of future misconduct would have been prevented but at a cost of 7,600 persons who would not commit misconduct being kept out of the legal profession. This would constitute overprediction of almost five to one.

But, it might be asked, could not the number of false positives (students erroneously predicted to be offenders) be reduced if there were a willingness to sacrifice some efficiency in spotting future offenders? After all, spotting 80 per cent of future offenders is pretty high. What if we were satisfied to spot only 60 or even 20 per cent of future offenders, would there still be so many false positives? The answer is no. The number of false positives could be reduced, if there were also a willingness to reduce the number of true positives, that is, the number of potential offenders correctly spotted. But the number of false positives—in both percentage and absolute terms—would still remain quite high, under the population at issue here.

This can be demonstrated by hypothesizing that a four-factor index is employed to achieve 80 per cent accuracy in identifying offenders and nonoffenders. Assuming that each of these factors were of equal predictive significance, there presumably would be a reduction of about 25 per cent in the accuracy of the index’s ability to spot future violators if one of the factors were converted from a “failing” criterion to a “passing” one—or put another way, if the “cutting line” were raised. There might also be an improvement of about 25 per cent in the index’s ability to predict nonoffenders.

Assume, for instance, that past record of dishonesty would no longer result in a failure. Obviously, some but not all persons with that record would become offenders. The elimination of the factor would result in a smaller number—and percentage—of failures among those taking the test. Included in the new group of “passers” would be some who, under the old test, would have been correctly identified as offenders and some who would have been incorrectly so identified.

What would the numbers look like under this new and more conservative index? Only 60 per cent of the potential offenders would be identified (80 per cent × .75). This would come to 1,200 of 2,000. But approximately 85 per cent of the nonoffenders would now be correctly identified. (The increase of 5 per cent is 25 per cent of the original 20 per cent inaccuracy.) This would still leave 5,700 false positives—students incorrectly identified as future offenders.

If one other factor were converted from a failing criterion to a passing one—if the cutting line were raised even higher—the number of future offenders correctly identified would be reduced to 800 (less than half), but the test would still produce about 3,800 false positives. If three of the four factors were converted, thus reducing the number of spotted future offenders to 400 of 2,000 (or a mere 20 per cent), the test would still produce 1,600 false positives. Even if the cutting line were raised further so that 99 per cent of all persons who failed would become offenders, there would still be approximately 380 false positives.

It is, of course, theoretically possible to reduce the number of false positives to any number desired by continuing to raise the cutting line until only “certain” future offenders were included. But that would probably bring the percentage of offenders spotted down below 1 per cent. It is unlikely that it would then be thought worth the effort to identify so small a percentage of future violators, especially since they would be the most obvious ones who probably would be weeded out by current practices.

There is simply no way to reduce the number or percentage of false positives to manageable figures, while still spotting any significant number or percentage of true positives. The reason for this inheres in the mathematics of the situation: whenever the base rate expectancy for a predicted human act is very low or very high—say, below 10 per cent or above 90 per cent—it becomes extremely difficult to spot those who would commit the act without also including a large number of false positives. And since the percentage of future offenders among the entering law school classes is extremely low—certainly not more than 5 per cent—it is not feasible to develop predictive criteria capable of sorting out the future offenders from the future nonoffenders.

The dilemma inherent in predicting disbarable conduct among first-year law students is illustrated in the accompanying table.

Total number of people being tested = 40,000 (#F + #P = 40,000).

Total number of anticipated future offenders (base rate expectancy) = 2,000 (TP + FN = 2,000).

Total number of anticipated future non-offenders = 38,000 (FP + TN = 38,000).

*[There is no fixed mathematical relationship between the percentage decrease in accuracy of an index’s ability to spot offenders and the increase in its ability to predict non-offenders. The figures used in the table are, in the author’s view a fair reflection of what might realistically be expected.]

Clinical Versus Statistical Prediction

The predictive test, of course, need not be used to disqualify automatically all those who fail it. It could be used simply as a screening mechanism to isolate from the large population a smaller group that could then be further interviewed and investigated. Only those who “failed” these additional “tests” would then be disqualified or discouraged from further pursuit of a legal career. Would not this variation reduce the number of false positives even further?

The short answer to this question—a question which raises a series of complex considerations—is that this variation might well reduce the number of false positives, but it would do so in essentially the same way that raising the cutting line of an objective test would do it. In other words, the decision by an interviewer or investigator to “pass” certain students who had “failed” the written test is conceptually parallel to the introduction of a new cutting line that has the effect of passing some who would have failed under a different cutting line.

Many people do not view it this way, because they regard the introduction of the human element—the interviewer or investigator—as an improvement, as an increase in sophistication and subtlety over the mechanically scored test. They believe that the human agency is capable of doing what the test is incapable of doing—using insight and experience to distinguish the true from the false positives within the population that failed the test.

But the available data lend no support to this belief. Indeed, in 1957, Paul Meehl, a distinguished psychologist and a clinician, wrote a book, Clinical versus Statistical Prediction, that summarized the literature comparing the accuracy of statistical predictions (those made by mechanically scored tests) and clinical predictions (those made by individual experts). His conclusion—one that is now widely accepted as confirmed—was:

As of today there are 27 empirical studies in the literature which made some meaningful comparison between the predictive success of the clinician and the statistician. . . . Of these 27 studies, 17 show a definite superiority for the statistical method; 10 show the methods to be of about equal efficiency; none of them show the clinician prediction better. . . . I have some reservations about these studies; I do not believe they are optimally designed to exhibit the clinician at his best; but I submit that it is high time that those who are so sure the “right kind of study” will exhibit the clinician’s prowess, should do this right kind of study and back up their claim with evidence.

A more recent comparison, published in 1966, also found that of forty studies examined, the actuarial technique was always equal or superior to the clinical mode. A paper published in 2002 summarizing the studies made after Meehl’s book concluded: “Since 1954 [the publication of Meehl’s book], almost every non-ambiguous study that has compared the reliability of clinical and actuarial predictions has supported Meehl’s conclusion.”1

There is thus no objective evidence to support the claim that the introduction of an interviewer or investigator would increase the accuracy of the predictions made by a mechanically scored test. There is some evidence that it might actually decrease its accuracy. Introducing an interviewer may well result in more of a sacrifice in the number of true positives spotted to achieve the same reduction in the number of false positives. In any event, even if the clinical prediction were as good as or even better than the statistical prediction, it is clear that every increase in accuracy in avoiding false positives could be achieved only at the cost of a decrease in accuracy in spotting future violators.

It is, of course, possible that an investigation would produce more information about applicants that would improve the accuracy of the prediction, i.e., that would lower the percentage of false positives by a greater degree than it would reduce the percentage of offenders spotted. But numerous studies have demonstrated that the accuracy of predictions does not necessarily increase—indeed, it sometimes decreases—as the result of more information being made available to the predicter.

It is important to note that this is not a case in which some competitive selection must take place anyway, and one additional factor is merely being thrown into the calculus. Once a student is admitted to law school, no further process of competitive selection is contemplated before he is admitted to the Bar. To be sure, there are processes of disqualification (for instance, failure in law school, on the bar examination or in the character examination), but that is a different matter. The proposal of the committee of the Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar would have been somewhat more defensible empirically, although it still would have been vulnerable on numerous grounds, if the predictive tests were to be administered to all law school applicants, and the results used as an aid in the competitive selection process. But in the last analysis, any attempt to predict attorney misconduct, whether among first-year law students or law school applicants, is necessarily doomed to failure.

As long as we are dealing with a population that includes so small a proportion of future violators, it will not be possible to spot any significant proportion of those violators without erroneously including a far larger number of “false positives.” This, in a nutshell, is the dilemma of attempting to predict rare human occurrences. And this is the dilemma that will inevitably plague the studies proposed by the committee.

Unless the legal profession is prepared for the “preventive disbarment” of large numbers of young students who might, if permitted to pursue their careers, practice law with distinction, it should not encourage the development of tests designed to predict potential character defects or misconduct among lawyers at an early stage in their legal education.