by Dr. Andy Lee Roth and Mickey Huff

In Ray Bradbury’s celebrated book Fahrenheit 451, the protagonist, the fireman Guy Montag, reaches a turning point after realizing that his actions at work, earlier that day, contradict his inner convictions. In their living room, with multiple entertainment screens bombarding them, Montag confesses this growing unease to his spouse, who refuses to consider his concerns. “Let me alone,” she says, “I didn’t do anything.” Montag responds, “We need not to be let alone. We need to be really bothered once in a while. How long is it since you were really bothered? About something important, about something real?”1

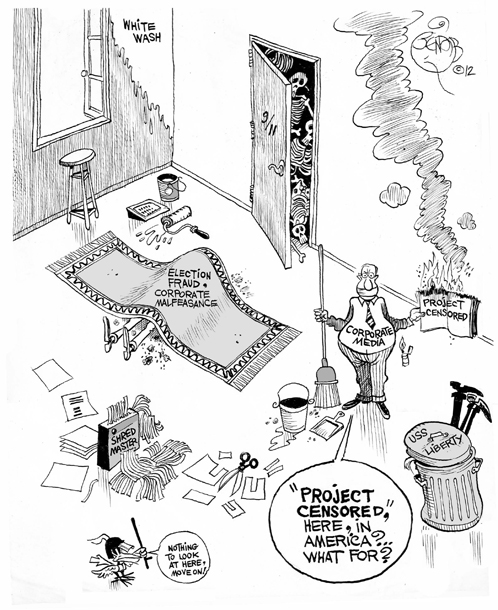

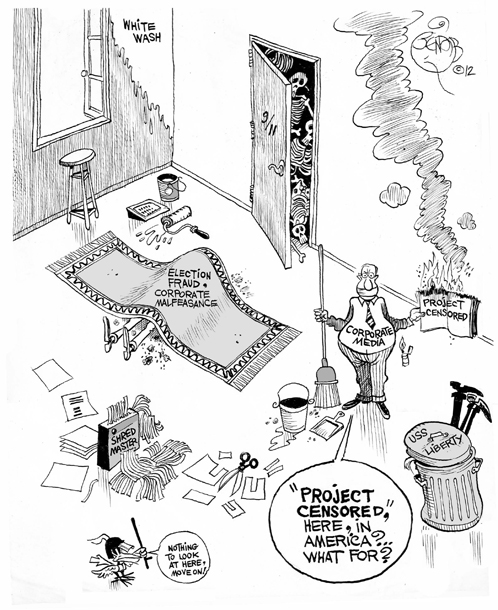

For anyone paying attention, the past year’s real news includes much about which to be bothered. Censored 2013 holds to account the corporate media who, all too often it seems, would rather be let alone than bothered when it comes to real, important news; and it celebrates the efforts of independent journalists who in 2011–2012 brought forward crucial news stories to stir us from complacency.

Pulitzer Prize–winning sociologist Paul Starr described a “serious long-term crisis” of news media in postindustrial democracies, including the United States: “The digital revolution,” Starr wrote, “has weakened the ability of the press to act as an effective agent of public accountability by undermining the economic basis of professional reporting and fragmenting the public.”2 Starr’s argument is important to understand for anyone interested in Project Censored’s work.

The diffusion of television channels and the development of the Internet mean that the segment of the public interested in politics “sees politics increasingly through the lens of polarized news media,” while an increasingly large segment of the population not interested in politics has “effectively dropped out of the public” and is “less likely to encounter news at all.”3

Recent poll data from the Pew Research Center supports Starr’s critical assessment. According to a September 2011 Pew report, negative opinions about the performance of news organizations now equal or surpass all-time highs on nine of the twelve core measures that Pew has tracked since 1985.4 According to one poll, conducted by Pew in July 2011, 66 percent of Americans feel that news stories “often are inaccurate,” 77 percent believe that news stories “tend to favor one side,” and 80 percent believe that “powerful people and organizations” unduly influence news, to consider just three of Pew’s core measures.

Starr argued that, as news organizations lose influence over public opinion, they become “less capable of standing up to powerful interests in both the state and private sector.”5 This ultimately threatens democracy, Starr argued, because studies show that “corruption flourishes where journalism does not.” The less news coverage, the more entrenched political leaders become and the more likely they are to abuse power.6

Starr’s analysis of news media in crisis is sobering for anyone who believes in the importance of a free press to democracy. His argument that the digital revolution has been good for freedom of expression and for freedom of information, but has ultimately weakened freedom of the press, is clear and original. However, by tacitly focusing on a crisis that confronts corporate news media most powerfully, Starr may overstate the crisis and risks overlooking the best solution to it.

Unlike their corporate counterparts, independent media have never generated large revenues from advertising; they have never taken for granted the ability to assemble a mass public on a daily basis; and they have, from their inception, treated standing up to powerful state and private interests as their core mission, their raison d’être.

Again, data from the Pew Research Center report proves useful to understanding the news crisis and its scope. In a June 2011 survey, Pew asked respondents what came to mind when they thought about “news organizations.” The most-named organizations were CNN (43 percent), Fox News Channel (39 percent), and the three TV networks (NBC News, 18 percent; ABC News, 16 percent; CBS News, 12 percent).7 The data indicate that, when asked about news organizations, most Americans identify corporate news media, particularly television.

As Censored 2013 demonstrates, independent media prove robust, even as corporate media undergo crisis, because independent news workers understand that news is a public good, not a commodity. To borrow a phrase widely attributed to historian Daniel Boorstin, author of The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America,8 in a democratic society, the value of news “increases by diffusion and grows by dispersion.” Project Censored, and the independent journalists and news organizations celebrated in Censored 2013, aim to contribute to that diffusion and dispersion on the belief that, through our continuing efforts, we will one day awaken the US public to the realization that independent media—not their corporate counterparts—constitute both the “mainstream” of healthy US journalism and the sturdy foundation of authentic democratic self-government.

INSIDE CENSORED 2013

As in previous years, Censored 2013 consists of three primary sections. Section I features Censored News and Media Analysis, including Project Censored’s venerable listing of the top censored news stories. Chap-ter 1 presents the Top 25 Censored Stories for 2011–12 in the form of five Censored News Clusters. As in Censored 2012, this year’s clusters draw analytic connections across multiple stories, elaborate on why some topics suffer from chronic underreporting in the corporate media, and address potential forms of engagement for an audience committed to more than just “consuming” the news. This year our chapter 1 team includes Elliot D. Cohen, Rob Williams, Elaine Wellin, James F. Tracy, Susan Rahman and Liliana Valdez-Madera. Of course, the identification, validation, and presentation of the top censored stories and their related Validated Independent News stories would be impossible without the hundreds of students and professors from colleges across the US and around the world, not to mention the courageous independent journalists who first reported these stories.

Chapter 2 , Censored Déjà Vu, revisits six selected Top 25 Censored Stories from previous years, focusing on their subsequent corporate coverage and the extent to which they have become part of broader public discourse, or whether they remain “censored” by the corporate media. A team of Project Censored interns, including Jen Eiden, Nolan Higdon, Aaron Hudson, Mike Kolbe, Michael Lucacher, Ryan Shehee, Juli Tambellini, Andrew O’Connor-Watts, provide updates on five top stories from Censored 2012—including soldier suicides, Obama’s international assassination campaign, Google spying, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, and labor abuses in Apple’s Chinese factories—and one from Censored 2008 on the Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act.

In chapter 3 , Mickey Huff, Andy Lee Roth and Project Censored interns Nolan Higdon, Mike Kolbe, and Andrew O’Connor-Watts survey Junk Food News and News Abuse, two fields that the corporate media liberally replenish every year. Comical as 2011–12 Junk Food stories may seem—like “Tebow Fever,” Kim Kardashian and royal weddings, news commentators arguing with Muppets, Donald Trump’s ongoing obsession with President Barack Obama’s birth certificate, and the return of the McRib—when analyzed in context they clarify how the infotainment of US corporate news serves serious propaganda functions, offering a diet of McNews no one can use. News Abuse examines cov-erage of conservative pundit Andrew Breitbart’s death, the “threat” of organized labor to the Super Bowl, and the scandal over Mike Daisey’s Apple exposé on NPR’s This American Life, among other stories, showing how the news frames employed by corporate media distort serious stories and spin them into the sensational and trivial while burying the real significance of the subject matter at hand.

By contrast, chapter 4 , on Media Democracy in Action, highlights local, national, and international organizations that exemplify independent journalism and activism in service of government transparency. This year, we proudly feature Yes! Magazine’s Sarah van Gelder on twelve helpful trends to extend in the coming year; Chris Woods of London’s Bureau of Investigative Journalism, which has been a leader in coverage of the US’s “covert” drone campaigns; MapLight: Revealing Money’s Influence on Politics; Michael Levitin of the Occupied Wall Street Journal; Victoria Pacchiana-Rojas on Banned Books Week; Christopher Ponzi of Rebellious Truths; Nora Barrows-Friedman of Electronic Intifada; Andrew Phillips of Pacifica/KPFA Radio; J. R. Valrey of Block Report Radio; and Steve Zeltzer of Work Week Radio. For the reader seeking models of civic action and free press principles, this chapter is for you.

Section II focuses on what Project Censored has called the Truth Emergency, which results from the lack of factual reporting by corporate media over the past decade.9 This year’s Truth Emergency section deconstructs narratives of power to reclaim the common good. Antoon De Baets presents a theoretical framework for analyzing censorship and related issues, including historical propaganda and the abuse of history. Peter Phillips and Kimberly Soeiro provide an organizational “X-ray” of the global ruling class; and Elliot D. Cohen examines the dramatic rise of electronic surveillance, including government programs aimed at Total Information Awareness that lead to social control. Adam Bessie analyzes the attack on public education posed by GERM—the Global Education Reform Movement—and deconstructs the frames of propaganda put forth by GERM’s Astroturf funders and political allies in both major political parties which mute the voices of those who should matter most in education: the students and teachers. Laurel Krause and Mickey Huff write to remind us about the importance of getting the past right, as they highlight recent evidence that significantly changes the historical record suggesting that the Kent State Shootings of 1970 were acts of state murder. We conclude this section of understanding conflicts between official and vernacular narratives with the hope to reclaim the common good. Kenn Burrows and Michael Nagler survey the new thinking and nonviolent actions that promise to aid humanity in responding to seven of the prominent challenges we face. They offer positive, proactive solutions to our current crises, solutions the corporate media simply don’t address.

The book’s third and final section, Project Censored International, provides five case studies in what we call “unhistory” in the making.10 Elaborating on a concept from George Orwell’s 1984, Noam Chomsky has defined an “unperson” as someone “denied personhood because they don’t abide by state doctrine”—thus, “we may add the term ‘unhistory’ to refer to the fate of unpersons, expunged from history on similar grounds.”11 While other chapters in this year’s book also address this issue, all of the chapters in the final section of Censored 2013 address the importance of recognizing “unhistory” and countering its withering effects on human rights and dignity. Almerindo E. Ojeda analyzes “Guantánamo Speak” and its role in the manufacture of consent; Andy Lee Roth reports on corporate media coverage of the United States’ targeted killing of US citizen Anwar al-Awlaki; Angel Ryono looks at the ongoing plight of Iraq’s refugees; Brian Covert recovers the forgotten history of Japan’s nuclear power industry, which prepared the road to disaster at Fukushima; and Tara Dorabji reports on the “occupation of truth” in Indian-administered Kashmir. Each of these news stories goes essentially untold in the corporate media, and the authors encourage us to retrieve them from the memory hole of “unhistory.”

“EVERYTHING TO THINK ABOUT,

AND MUCH TO REMEMBER”

Censored 2013 represents the accumulated knowledge of Project Censored’s thirty-six years and the tireless efforts of scholars, students, activists, and community members from around the world. Like Montag, the protagonist in Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, as individuals, we may find the choice to engage unsettling. Acknowledging the extent of the troubles, crises, and misconduct can be overwhelming. It takes courage. But, just as Bradbury’s character eventually comes to know others who share his concerns, the choice to engage connects us with others. The necessity of engagement outpaces the false comfort of complacency.

As Fahrenheit 451 concludes, Montag has escaped what amounts to a targeted killing (another dimension of our current crisis that Brad-bury presciently foresaw), and he has found the companionship of a band of people committed to remembering the past. Outside the burning city, they walk together, for the time in silence. “There was,” Bradbury writes, “everything to think about and much to remem-ber.”12

Welcome to Censored 2013: Dispatches from the Media Revolution. Thanks to our courageous independent journalists and our many generous contributors, it too offers much to think about and remember. Read some of what Censored 2013 has to offer and we believe that you, too, will be energized to address one of the many social problems it identifies, to make our communities and the world a better place to live for all.

Notes

1. Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451, 50th anniv. ed. (New York: Ballantine, 1991), 52.

2. Paul Starr, “An Unexpected Crisis: The News Media in Postindustrial Democracies,” Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 17, no. 2 (April 2012): 235.

3. Ibid., 238.

4. Pew Research Center, “Views of the News Media, 1985–2011: Press Widely Criticized, But Trusted More than Other Information Sources,” September 22, 2011, http://www.people-press.org/2011/09/22/press-widely-criticized-but-trusted-more-than-other-institutions.

5. Starr, “An Unexpected Crisis,” 240.

6. Ibid.

7. Pew, “Views.” Figures add to more than 100 percent because of multiple responses.

8. For more on Boorstin, see chap. 3 of this volume as we expand upon the thesis of his book The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America (New York: Vintage, 2012 [1961]).

9. On Project Censored’s conception of Truth Emergency, see Peter Phillips, Mickey S. Huff, Carmela Rocha, et al., “Truth Emergency Meets Media Reform,” chap. 11 in Censored 2009: The Top 25 Censored Stories of 2007–08, eds. Peter Phillips and Andrew Roth (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2008), 281–95; and Peter Phillips and Mickey Huff, “Truth Emergency: Inside the Military Industrial Media Empire,” chap. 5 in Censored 2010: The Top 25 Censored Stories of 2008–09, eds. Peter Phillips and Mickey Huff (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2009), 197–220.

10. For more on the concept of “unhistory,” see Noam Chomsky, “Anniversaries from ‘Unhistory,’” In These Times, February 6, 2012, http://www.inthesetimes.com/article/12679/anniversaries_ from_unhistory. Also see the introductions to sections two and three of this volume.

11. Ibid.

12. Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451, 164.