• • • •

Two decades ago the idea that human geneticists could ever generate the genomes of individuals belonging to extinct species of our genus Homo was unthinkable for many technical reasons. Since then, however, the technology has moved along so quickly that obtaining the genomes of extinct or long-dead individuals has by now become almost commonplace. The advances that have allowed this amazing technical breakthrough have involved both laboratory refinements and “informatics” tricks that depend on computer wizardry.

As an example of what has been achieved, imagine that a Neanderthal passed away some forty thousand years ago, at the impressive old age of forty. His remains would have decayed via both microbial and molecular interactions, a set of processes on which his environment of interment would have had some impact. When we and other organisms are alive, we are packed with microbes. Most of them are harmless or even beneficial to us. We need to stave off the most nefarious of them, but for the most part we live in relative harmony with these tiny, single-celled cohabitants, our immune system constantly working to keep the worst of them from getting out of control. But when we die our immune system stops working, and our remains become a haven for microbes that were kept at bay or only infested us in small numbers when we were alive. So it was for Neanderthals, too.

Once those destructive microbes had taken hold of his body, our deceased Neanderthal would have begun to decompose via those microbial and molecular processes. As the nutrients in his corpse were used up, the microbes themselves would have started to die, leaving their own DNA hanging around the fossilizing tissues. If the Neanderthal had died in a moist, humid resting place, so much for the DNA of Neanderthal and microbes alike: it has been estimated that intact DNA can only exist in the presence of significant amounts of water for something like ten thousand years, at which point it will have been entirely fragmented into single bases and be useless for DNA sequencing. But if, on the other hand, our Neanderthal had happened to pass away in a dry, cool cave, his DNA would have broken down much more slowly. His fossilizing corpse would still have had loads of microbial DNA bound up in it; but at least all his own DNA would have stayed relatively intact for longer. And although his fragmented DNA would nonetheless be in pieces not much more than a hundred bases long by the time a few tens of thousands of years had passed, with the right algorithms and with intensive computation, it might still be possible to reassemble his DNA from the fragments.

The problems of microbial contamination and the extensive fragmentation of the DNA strands are also complicated by the fact that people working with the bones leave traces of their own DNA on the fossils, both as they are excavated and as they are worked on in the lab. The resulting complications are fiendishly daunting; but one diligent and dedicated researcher has made all the difference in this field. Svante Pääbo, now at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, dedicated his career to working on these problems, and he and his colleagues eventually overcame all the technical difficulties using clever biochemistry and computational methods. In doing so, they established the field of ancient human genomics, in which several other laboratories are now also active.

Most of the archaic human fossils sequenced so far have been less than forty thousand years old. However, in some cases of exceptional preservation, the boundary can already be pushed. The oldest human DNA so far analyzed comes from five bones, among several thousand found in the Sima de los Huesos (“Pit of the Bones”) in northern Spain, that date back to around four hundred thousand years ago. And perhaps even more remarkably, DNA has permitted the detection, from one tiny finger bone found in Siberia’s Denisova Cave, of an entirely new kind of extinct hominid that could not have been recognized in any other way. Indeed, we still do not know what those extinct “Denisovans,” contemporaries of both Neanderthals and the earliest European modern humans, would have looked like physically. We just know they were genomically distinctive.

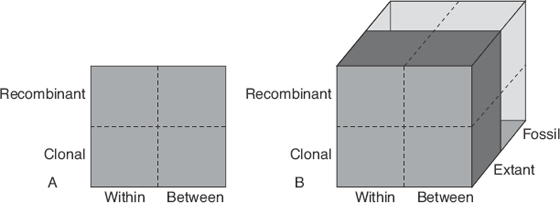

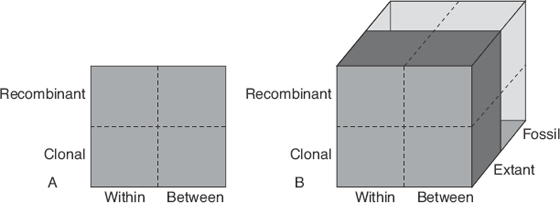

The addition of ancient genomes to the fray has facilitated a whole new dimension of analysis and hypothesis testing in paleoanthropology (figure 9.1). Before ancient DNA could be easily manipulated for whole-genome sequencing, when tissue from living or recently dead individuals was required the kinds of questions that could be asked were limited. What is more, the ease with which data on clonal DNA could be generated and analyzed ensured that the most studied quadrants in figure 9.1 were the clonal ones. But recently, the upper quadrants have been the focus of a lot of research, with worldwide studies in the HGDP and 1000 Genomes Project focusing on the upper right quadrant.

Sequencing ancient mtDNA from archaic Neanderthal and Denisovan specimens first focused on sequencing what is called the HV1 region of the mtDNA. The HV1 sequence is a non–protein coding region of the mtDNA genome that is variable enough to allow for fairly accurate placement of its variants in a phylogenetic tree. The phylogenetic tree of this clonal marker revealed several longish basal branches of Neanderthals, mostly from Central Asia, and a cluster of more recently diverged Neanderthals (circa fifty thousand years old) exclusively from Europe. The authors of this analysis suggest that the European Neanderthal populations diverged before our own Homo sapiens migrated into Europe.

Figure 9.1 Human origins analysis space. The left diagram shows the space without ancient DNA. The y-axis determines whether the DNA comes from mt genomes or the Y chromosome (clonal) or the autosomal nuclear and X chromosome (recombinant). The x-axis determines whether the analysis is done within or between taxonomic units. Addition of the temporal framework (z-axis) makes for a widening breadth of questions to be asked. So, for instance, a population study of Taiwanese mtDNA lineages would fit in the lower left quadrant of figure A and a worldwide survey of Y-chromosome variation would fit into the lower right quadrant of figure A. A study of genomic variation of people from the British Isles would fit into the upper left quadrant, and a study of variation of chromosome 21 across European populations would fit into the upper right quadrant and so on.

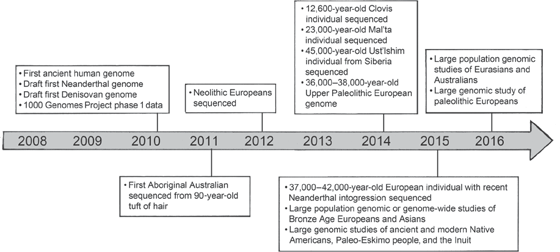

Several Neanderthal and a few Denisovan complete mtDNA genomes have been sequenced, and used to address Neanderthal relationships and the placement of Denisovan specimens in the human family tree. They also revealed a great deal of variation among the maternal lineages of these extinct human taxa. By now, the nuclear genomes of three Neanderthal specimens and one Denisovan specimen have also been sequenced to low coverage. These studies fit into the rearward quadrants of figure 9.1, because they have been compared with a wide array of living Homo sapiens genomes. Figure 9.2 shows the phylogenetic tree generated from the seven full Neanderthal mtDNA genomes and two Denisovan mtDNA genomes currently available, along with several human lineages. This tree is similar in many ways to the tree generated from HV1 region sequences. In both analyses, the Denisovan sequence was used as an outgroup to root the trees. Addition of an mtDNA genome sequence from a 430,000-year-old specimen from the Sima de los Huesos (figure 9.2) suggested that this older specimen’s mtDNA is more closely related to Denisovan than to Neanderthal mtDNA.

In a truly spectacular development in 2017, researchers at the Max Planck Institute, led by Pääbo, guessed that DNA from archaic humans might be recoverable from the sediment present at archaeological sites. Their reasoning stems from the idea that remains or products of organisms can complex with minerals in the sediment; and while they might not necessarily be preserved as visible fossils, their nucleic acids just might still be there. Because the sediment will include microbial DNA and that of any other animals that might also have been present (bovids, canids, felids, rodents, elephants, ursids, cervids, etc.), special sequence data analysis filters were developed to separate the human sequences from everything else. In addition, the researchers obtained DNA from different sedimentary layers, which allowed them to determine which humans were present during different time frames. Their work has recovered a familiar phylogenetic tree from these samples, but it shows that the Denisova Cave had several Neanderthal residents in addition to the Denisovans (figure 9.3). The study also adds to the range of Neanderthal variation available.

Figure 9.2 Phylogenetic tree of Sima de los Huesos, Neanderthals, H. sapiens, and Denisovan specimens for whole mtDNA genomes. The Bayesian approach was used to generate the tree. The Bayesian posteriors at the node defining Neanderthals is 1.0, which suggests a high degree of confidence of the existence of that node. Redrawn from Skoglund et al. (2014).

Figure 9.3 Phylogenetic tree of bone-derived complete mtDNA sequences from Sima de los Huesos, Neanderthals, H. sapiens, and Denisovans along with sediment-derived mtDNA genomes from Neanderthals and Denisovans. In this tree, the locations of the archaic hominins are used as terminals. Redrawn from Slon et al. (2017).

The mtDNA results seem to show that, among the taxa analyzed, Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens are each other’s closest relative, with Denisovans and Sima de los Huesos populations showing closer affinity to each other than to either H. sapiens or Neanderthals. But what about the rest of the genome? As we have already pointed out, sequencing nuclear genomes is much more difficult than sequencing mtDNA; and while hundreds of ancient mtDNA genomes and tens of thousands of living H. sapiens mtDNA genomes have been sequenced, it seemed for a while that large numbers of fossil nuclear genomes would be unattainable due to the expense and labor involved. But again, Pääbo and other researchers have developed techniques to more easily secure archaic human and ancient human genomes. The added temporal dimension, and the ability to include nuclear genomes, opens up a wide range of novel and essential questions about human origins and ancestry.

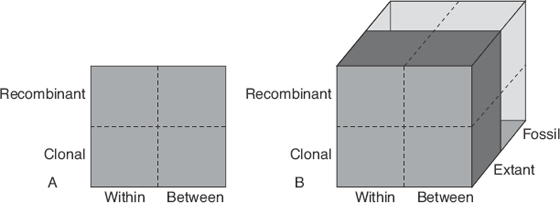

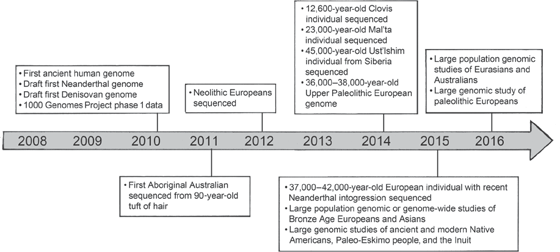

The biologists Montgomery Slatkin and Fernando Racimo pointed out in a recent review of ancient human genomes that nearly one hundred such “paleogenomes” have been sequenced in the past six years, most of them completed in 2016. And it is hardly an exaggeration to claim, as Slatkin and Racimo did, that a “paleogenomic revolution” has occurred in a very short span of time. Figure 9.4 shows the rapidity with which this field has developed. One of the major developments in this timeline is the completion of the 1000 Genomes Project phases 1 and 3, because the inclusion of the 1000 Genomes Project database, made up of geographically diverse living humans, is essential to interpreting what we see in the archaic individuals. And interestingly, in this context we see a very different picture from what we saw from mtDNA alone. For the nuclear genomes indicate that Neanderthals and Denisovans are each other’s closest relatives, while Homo sapiens is the “odd man out.” In addition, when the nuclear DNA of two Sima de los Huesos specimens is added, these humans no longer appear most closely related to Denisovans, but rather are sisters to Neanderthals (figure 9.5).

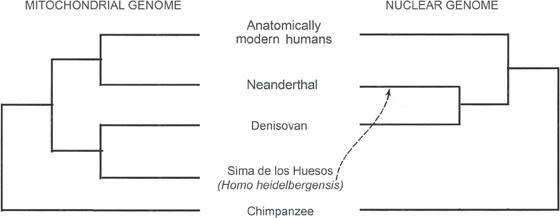

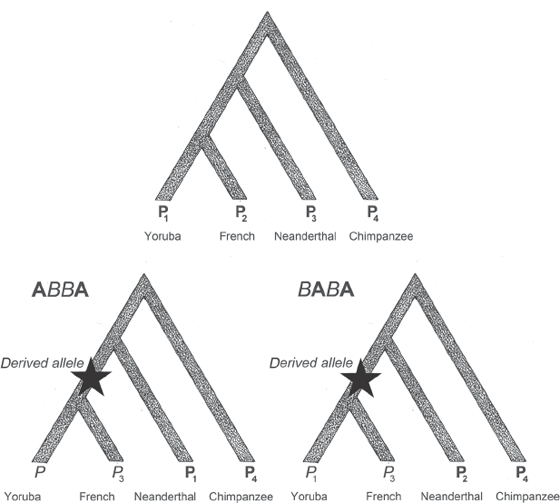

While the inferences concerning relatedness among Neanderthals, Sima de los Huesos, Denisova, and our own species are certainly intrinsically interesting, perhaps the most striking and controversial result of the sequencing of these archaic humans comes from the light they shed on the ancestral makeup of our own genomes. To do this, researchers developed what they call the ABBA/BABA test (figure 9.6). The test requires an outgroup reference sequence. Any sequence outside of the Neanderthal/Denisova/Sima de los Huesos group will do the trick, and researchers settled on the chimpanzee lineage because it is the closest living relative for which we have genome sequences. The test is accomplished by comparing two modern human lineages (in figure 9.6 these two lineages are Yoruba and French). Finally, an archaic genome is also included (in figure 9.6 the archaic genome is from Neanderthal). The “real” history for any SNP in the genome is displayed at the top of the figure. In this diagram, the two modern human groups should be sister terminals. However, there will always be some SNPs that do not reveal this history. Remember from chapter 3 that there are three possible trees when we have three ingroups and one outgroup. So there are two other possibilities—one in which the first modern human group is sister to Neanderthals, and one in which the second modern human group is sister to Neanderthals (French/Neanderthal vs. Yoruba/Neanderthal).

Figure 9.4 Timeline showing the development of whole-genome sequencing for ancient (fossilized modern H. sapiens) and archaic humans (Neanderthals and Denisovans). From Nielsen et al. (2017).

Figure 9.5 MtDNA genome phylogenetic tree (left) and nuclear genome tree (right). The trees are from Ermini (2014), but the Sima de los Huesos data were generated in 2016; hence the arrow indicates the position of the Sima de los Huesos lineage.

Figure 9.6 The ABBA/BABA test. The top tree is the “real” or expected tree. The bottom, left tree is the ABBA tree (French with Neanderthal), and the right tree is the BABA tree (Yoruba with Neanderthal). Individuals are numbered as P1 (Yoruba), P2 (French), P3 (Neanderthal), and P4 (chimpanzee). The agreement of the SNP with the tree is accomplished by examining the state at the node with the star labeled “derived state.”

One simply sifts through the sequence data and assesses for each SNP whether it supports the “real” tree—and, if not, which of the other two trees the SNP supports. The test then compares the tallies for the three trees. The number used to summarize the analysis is called the D statistic, and is given by the simple ratio of the number of ABBA SNPs minus the number of BABA SNPs, divided by the number of ABBA SNPs plus the number of BABA SNPs. If the D statistic is positive, it means that there are more ABBA SNPs than BABA SNPs, and hence that more Neanderthal SNPs resemble Yoruba SNPs. On the other hand, if the D statistic is negative, there are more BABA SNPs, meaning that more SNPs support a Neanderthal-French relationship. If the evolution of all the SNPs is regular, the D statistic should be 0.0. But if there is something odd occurring, a positive or negative D statistic is obtained, and the magnitude of the D number tells us how much hanky-panky is going on. Table 9.1 shows the results of applying the ABBA/BABA test to several modern human individuals. Note that in the D column of the table the only values that are significant are comparisons of non-African with African, and that the values are between D = −3.8 and D = −5.3. These results indicate that there is an excess of Neanderthal-like sequences in non-African genomes.

But what kind of hanky-panky could cause a nonzero D statistic for a comparison? Remember that the nuclear genome undergoes recombination during sexual reproduction. One mechanism might be interbreeding between the Neanderthal and Homo sapiens lineages. This would not be unexpected, since very closely related species are often observed to interbreed if they have the opportunity—even though, if they truly are different species (as seems to have been the case with Neanderthals and ourselves), this behavior will not lead to reintegration of the two lineages. Still, if Neanderthal individuals had mated with members of our species during their brief time of geographic overlap, then part of the Neanderthal genome might have recombined into H. sapiens genomes. In which case, we would expect chunks of the H. sapiens genome to resemble their counterparts in Neanderthals, making the D statistic nonzero. Alternatively, simple convergence of DNA sequences might have occurred because of independent mutations in the two lineages, leading again to a nonzero D statistic. This is also nothing unusual, though it requires a completely different mechanism. And there is a third way in which the D statistic might be nonzero: the SNPs might have sorted before speciation, something that also happens more frequently than you might think. All these possibilities are perfectly okay as scenarios to explain a nonzero D result, especially when you consider what we have said about genes in the genome often having different histories. But one helpful thing to consider in choosing among them is that is that chunks of DNA will be convergent in the hybridization scenario, whereas in the other two scenarios, the convergent SNPs will be randomly dispersed.

TABLE 9.1

ABBA/BABA Results from the First Neanderthal Genome Sequence Paper

| H1 |

H2 |

H3 |

Number ABBA |

Number BABA |

D |

Z score |

Interpretation |

| San |

Yoruba |

Neanderthal |

99,515 |

99,778 |

−0.1 ± 0.3 |

−0.4* |

Neanderthal equally close to Africans |

| French |

Han |

Neanderthal |

74,477 |

73,089 |

0.9 ± 0.5 |

1.7* |

Neanderthal equally close to non-Africans |

| French |

Papuan |

Neanderthal |

70,094 |

70,093 |

0.0 ± 0.5 |

0.0* |

Neanderthal equally close to non-Africans |

| Han |

Papuan |

Neanderthal |

67,022 |

68,260 |

−0.9 ± 0.6 |

−1.4* |

Neanderthal equally close to non-Africans |

| French |

San |

Neanderthal |

95,347 |

103,612 |

−4.2 ± 0.5 |

−9.3 |

Neanderthal gene flow with non-African |

| French |

Yoruba |

Neanderthal |

84,025 |

92,006 |

−4.6 ± 0.4 |

−10.5 |

Neanderthal gene flow with non-African |

| Han |

San |

Neanderthal |

94,029 |

103,590 |

−4.8 ± 0.5 |

−9.9 |

Neanderthal gene flow with non-African |

| Han |

Yoruba |

Neanderthal |

82,575 |

91,872 |

−5.3 ± 0.5 |

−10.5 |

Neanderthal gene flow with non-African |

| Papuan |

San |

Neanderthal |

90,059 |

97,088 |

−3.8 ± 0.5 |

−7.0 |

Neanderthal gene flow with non-African |

| Papuan |

Yoruba |

Neanderthal |

79,529 |

85,570 |

–4.2 ± 0.6 |

–7.5 |

Neanderthal gene flow with non-African |

*Z scores are significant.

Source: From Green et al. (2010).

The first study using this approach estimated that up to 4 percent of the genomes of non-African individuals could be said to have chunks of Neanderthal DNA embedded in their genomes. Using the same approach, but using Denisovan instead of Neanderthal SNPs, and comparing them to the genomes of Oceanian people, the researchers later suggested that up to 6 percent of the Oceanian genome is made up of introgressed Denisovan genomic DNA. A further study, using more Southeast Asian, Oceanian, and Australian modern human genomes, claimed to pin down the general location of interbreeding to Southeast Asia. This last inference also suggests that Denisovans occupied a very broad range of habitats, stretching all the way from the frigid Russian steppes to the steamy tropics. Only one other human species—Homo sapiens—has ever occupied such a wide range of habitats.

The controversy over whether biological mixing is the cause of the observed ABBA/BABA patterns is a genuine one, and several studies have challenged the validity of blaming sexual hanky-panky for these patterns. For instance, Anders Eriksson and Andrea Manica have tweaked the population structure models used in ABBA/BABA measures to reach the conclusion that there is no statistical difference between the probabilities of the sorting and interbreeding scenarios. In a similar vein, William Amos (2016) has recently adjusted the assumption that mutation rate needs to be constant to show that slightly altered mutation rates in the derived Homo sapiens populations could produce the divergent ABBA/BABA patterns with respect to Neanderthal comparisons with non-African lineages.

The estimate of the quantity of Neanderthal introgression seems recently to have dwindled to about 2 percent, while the claim that there was no introgression of Neanderthal DNA in African populations has recently run into challenges. In combination with scientists’ capacity to alter the inferences by tweaking the assumptions of the models used, these findings suggest that the dramatic scenario involving hybridization between the morphologically very highly divergent H. neanderthalensis and H. sapiens continues to be a moving target. On the other hand, based on current information, the Denisovan introgression story seems to be on firmer ground.

Still, the story of the Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans does carry a very clear moral. Whatever it was that actually happened, all three lineages evidently maintained their distinctive identities, and they certainly experienced independent evolutionary fates. And whether—or not—members of modern Homo sapiens boast any “Neanderthal genes,” they remain very much themselves, at most only marginally affected by any ancient hanky-panky. This picture contrasts starkly with what we see today. For even though lineages have clearly diverged within our unprecedentedly geographically widespread species, those lineages invariably show an irresistible tendency to reintegrate when they have the opportunity.