[PSS 83/80]

1 September 1869. Moscow.

Nº 37 – LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY ![]() SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

[PSS 83/80]

1 September 1869. Moscow.

To be read when you are alone.

The whole day I spent in enquiries and uncertainty as to which route to travel: through Morshansk or through Nizhnij [Novgorod].223 Il’ina,224 who was riding with me to Moscow, assured me that it was better to head towards Morshansk. But from all the enquiries I made here — at the post office and with the brother of the Manager of the Penza Village whom I found here, I deduced that the route to Morshansk was uncertain and I could [easily] get lost, and so I decided to head towards Nizhnij. Hence you should write to me at the post office in Saransk, and to Sobolev’s hotel in Nizhnij. The manager’s brother is a rich merchant in Moscow, and from my conversations I gather that his brother has a comfy job there (he has been manager for 15 years already), and that he does not look favourably on a [potential] buyer. That cursed Ris has nothing ready; I haven’t seen his corrected proofs, and probably shan’t be able to take them with me.

I didn’t see Golitsyn225 and probably shan’t. Yesterday I had nothing to eat along the road, and so to have supper and enquire about the route, I went to a club, where I didn’t find out any specific information. There I met up with Mengden,226 Sobolevskij227 and Fonvizin.228 I left directly after supper. My liver still hurts, but not as much [now], it seems.

Since it’s not yet 2 o’clock, and the train leaves at 5, I’d like to go see the Perfil’evs,229 to see whether they have any details about Penza. I met Sukhotin,230 of course. Among other things he told me that [Prince Pëtr Andreevich] Vjazemskij had written some humorous verses about [some] people at the court, such as:

Tolstaja231 makes fun of Trubetskoj.232

In her I see a tempering of the Tolstoys,

A seventh part of War and Peace —

I thank you — a surprise release!

Solovëv233 has only 500 roubles. He says things are tight for him both because it’s summer and because they’re still waiting for Volume 6 [of War and Peace].

I am always with you, and especially when we’re apart I find myself in a soft and humble mood. This was the mood I was in when I arrived at Tula and had the misfortune to see [Aleksandr Mikhajlovich] Kuzminskij — a cold, shallow and evil egotist. It was painful for me to get angry at him, but I had no other choice. I am sure he did not let Tanja go [anywhere]. He is one of those people who takes pleasure in doing unpleasant things for others. I am sure he enjoys his dinner more if he takes it from someone else. —

I bought some books and bouillon; the wine I shall buy at Nizhnij. At Shilovo I shall find out for certain whether I can go to Morshansk. But should I? In any case I shall go back to receive your letters.

Farewell, darling.

L. T.

I’m leaving the letter unsealed [for now]. I shall add a postscript at the Perfil’evs’ on my way back.

I didn’t find anyone at the Perfil’evs’ except Nastas’ja Sergeevna,234 and I’m off to Nizhnij [Novgorod] and shall return, too.

Nº 38 – SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA ![]() LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY

LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY

[LSA 26]

4 September [1869]. Evening. [Yasnaya Polyana]

I’m already experiencing moments of utter despair over your absence, and [wondering] what’s happening with you, sweet Lëvochka, especially when the day draws to a close and I’m left all alone in the evening with my dark thoughts, conjectures and fears. It is so hard living in this world without you; everything’s not as it should be; it seems everything’s wrong and it’s not worth it. I wasn’t going to write to you anything of the sort, but it came out all by itself. And everything’s so confined, so trifling, that I need something better, and that ‘better’ is none other than you, and always you alone.

I received a letter for you from Alexandrine in Livadija,235 written on your birthday [28 August]. She writes you a lot of tender [words], which I find annoying. She writes along the lines of your last letter to her and your last mood — preparation for death, and I thought it might be better for you if you had married her back then instead, you would have understood each other better. She is so eloquent, especially in French. One thing she notes with justification is that because of her unhappy love she has come to regard everything from the point of view of death, but she writes that she doesn’t understand how you arrived at that; it seems she wonders whether you might have reached this [conclusion] through the same route. She made me wonder, too — whether in your case it wasn’t because of an unhappy love, but because love gave you too little, that you adopted this comforting view of life, people and happiness. Now I’ve more or less retreated into myself, and am looking outward from myself to see where my own comforting path may lie. I wanted to somehow escape from the bustle of my routine life which has so utterly swallowed me up, to get out into the light, find some activity that would give me greater satisfaction and delight, but what that is I have no idea.

You should just hear how little Tanja asks and talks so much about you at every opportune moment — you would be delighted if you heard [her]. Serëzha has asked twice, while Il’ja doesn’t comprehend at all: poor thing, Serëzha shoved the door right into his nose and made it bleed, and he keeps wheezing and sneezing. Little Tanja is quite healthy; Mamà, Auntie and everybody are all doing fine, but my throat hurts very badly and I’ve lost my voice. Somehow Dasha236 frightened all of us. For twenty-four hours the other day she was perilously close to death. They sent a rider to fetch Mamà; she [Dar’ja] had a fever and was vomiting frightfully. The doctors summoned Knertser;237 now she’s quite better, the fever’s lessened, and the vomiting’s stopped; she had an attack of diarrhœa. The husband and wife [Aleksandr and Tat’jana] are getting on well again; Mamà says that he is very affectionate and tender with her, puts her to bed; pity he has such a changeable mood.

It’s not that good for you to go away from me, Lëvochka; I’m left with an angry feeling over the pain caused by your absence. I’m not saying this means you shouldn’t go, only that it’s harmful, the same as I don’t say [one] shouldn’t give birth, I’m only saying that it’s painful.

Our life is very peaceful here, there’s been no one around, — I hardly sleep at all at night, I get up at nine o’clock (our hours are now back to normal), we take tea all together, every day I read with Serëzha, and he writes; I sew, knit, quarrel with Nikolaj238 sometimes, in the evenings I read [Mrs.] Henry Wood;239 it’s easy to read her novels — they’re more understandable than others. When I breast-feed Lëvushka,240 I always philosophise, dream, think about you, and so these are my favourite moments [of the day]. Yes, it’s funny that yesterday the postman brought me two letters — from you and Alexandrine, and both of them contained Vjazemskij’s quatrain, which greatly flattered Alexandrine, and this I found funny.

It’s almost incredible that you won’t be coming until the 12th. You can’t expect me to calmly wait out another eight days, when these five have seemed to me a century. And now, probably, you haven’t quite reached your destination. I shan’t ask you to do anything more in Moscow. Hurry home quickly from Moscow; it’s silly to [think] of saving a few kopeks on [the more expensive] groceries in Tula at the expense of the several hours that I am deprived of your company.

For some reason Mamà wasn’t in a good mood yesterday, and overall her mood has completely changed since she visited the Kuzminskijs and saw their dysfunctional ménage. There’s a whole lot I could write to you. I keep thinking throughout the day how I want to write this to Lëvochka, and now I’ve forgotten so much and this letter has turned out all muddled; I was telling you that I’ve got unaccustomed to writing letters; I’d like to just tell you right off everything I want to say, but I can’t do it all at once. Here you are forced to read my letter, my rambling, while if you were at home you would say I’d do better talking to the samovar. I just remembered that and it offended me. So farewell, even though I’m annoyed with you, as here I am tormenting myself on account of your absence. Still, big hugs and kisses. I, too, want to say, as do the Aunties,241 May God preserve you. It will be a long, long time before we see each other again.

Nº 39 – LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY ![]() SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

[PSS 83/87]

11 or 12 June 1871. Steamship on the Volga.

I’m writing to you on board a steamship. The letter will be despatched from our first port of call.

There was so much going on in Moscow that I couldn’t get around to it. Especially since my decision as to whether to go to Saratov or Samara was made just an hour before departure.

I shall write it all out to start with.

I went straight to see Vasin’ka.242 Volodja243 went directly to Petersburg. Vasin’ka wasn’t at home, but he soon arrived. About where to find koumiss they weren’t able to tell me anything. The money — 75 roubles instead of the 100 I was expecting — he handed over to me. That evening I sent a wire to Zakhar’in244 at Bratsovo. In the morning I went to do some shopping, to find a nanny and a doctor, and found all except a doctor. —

There was no [doctor] in the town, and I decided not to go to the dacha to fetch Pikulin245 or Zakhar’in, who sent me a wire inviting me to dinner, for that would have delayed me a whole day. We know what the doctors would have said: they would have said there was nothing of significance, and that it wouldn’t harm me to travel. For a long time I wrestled with the question of where to go. [Pëtr Ivanovich] Bartenev, who had bought an estate at Atkarsk, assured me that there was good koumiss there. Vasin’ka said the same about Saratov. But the Tambov doctor Filipovich,246 and Leont’ev,247 whom I met, as well as [Jurij Fëdorovich] Samarin, all declared that undoubtedly and incomparably the best climate and koumiss recognised by all doctors was in the Samara [region]. Along the way I met another doctor, along with [several] knowledgeable people who all confirmed that Samara was the best, and [so] I am going back to my old place.248 Write to me, please, as soon as you can, at Samara until I send you another address. I’ll arrange with the Samara post office as to how to reach me. —

Now about nannys. I’m afraid that [big] Tanja will have trouble [understanding] my telegraphically brief letter. I went to see the German pastor. The pastor himself249 and especially the elderly widow Dikgof250 gave me five addresses, of which I have been to two. One of them was not at home. Stëpa251 located the other — the one whom Mrs. Dikgof recommended the highest, and whose address I sent [to you in a previous letter]; [her name is] Lindgol’m [Lindholm] — and she came to see me. She’s 25 years old. She served as a nanny for 6 years, it seems, in one place, at Mezentsov’s.252 She is not that nice to look at. But she seems to be an honest girl, healthy and unspoilt. She’s agreed [to work] for 12 roubles [a month], with the possibility of a raise in the future. I wrote out her duties: looking after [our] two elder children, maintaining their clothing in order, sleeping with them and sewing [for them]. And teaching them to read and write German. [Her] German is good. She speaks Russian. I would [recommend] hiring her. She asks that her way be paid to Tula, and that after a year she be given a return ticket, if you don’t get along. I said nothing. She promised to wait five days for a reply. If [we] don’t like her [we shall] send her back to Moscow — never mind the extra 3 roubles. We can send her 3 roubles through Vasin’ka — i.e. write her that she can stop by his place, and write to Vasin’ka to give her [the money].

I haven’t received the money from the [vegetable] oil salesman yet — he promised but didn’t come, so it’ll be up to you to collect what he owes [us].

I bought an excellent dish with enhancements, and it is being shipped along with a [a game of] pas-de-géant, which I bought from Puare253 for 28 roubles. To set up the pas-de-géant, call the men together and try to understand and follow [the instructions].254

The things will be sent out on Wednesday. My health is not just all right, it seems to me actually quite good. Hugs and kisses to the children, to yourself and to everybody there. Please do write in more detail. I’m very happy to see Stëpa. He’s very meek and kind. Ljubov’ Aleksandrovna is probably [staying] with us; hugs and kisses to her and Slavochka [i.e. Vjacheslav Andreevich Behrs]. I’m simply delighted that she’s with you.

Nº 40 – SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA ![]() LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY

LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY

[LSA 29]

[17–18 June 1871. Yasnaya Polyana]

It is not in a cheerful mood that I write you [today], sweet friend Lëvochka. My nanny’s ill and Lëvushka, too, has a fever and was vomiting. All this has been a great bother, but I’m not letting myself get depressed — I’ve been getting excellent help from Mamà, and Hannah, and Liza and Varja. When you’re not here I take very good care of myself, I take a nap during the day, I go out for walks, and so forth. The other children — indeed, all of us — are healthy. The children enthusiastically devour [wild] strawberries, they’re cheerful, and are out right now for a walk with Grandmother,255 since Hannah is busy helping me. Lëvushka [i.e. their son Lev] is getting along a little better now, and Nanny, too. Probably, by the time you receive this letter, everything here will be just fine once again. I’ve just received your letter from the steamer256 and I’m very happy that you’re feeling fine. Along with your letter I also received letters from Fet257 and Urusov.258 Urusov wrote me such a precious, intelligent letter that I find myself loving him even more. And Fet, as always, speaks and writes so grandiloquently.

You ask me to write in more detail, but unfortunately I don’t really have time for that today. I really love writing to you — it comforts me to send and receive letters. I am sending you my [new] photo. I had it taken the other day, on Tuesday, at Tula, where I went with Liza and Leonid.259

Your jury duty has been causing us no end of troubles. We obtained the [medical] certificate from Knertser, sent it with Ivan Kuzmich to Sergievskoe, and now the penalty has been lifted and the certificate accepted. There’s been a big fuss about money, too — the 1000 silver roubles which were sent to you in care of [Aleksandr Mikhajlovich] Kuzminskij. Here we made use of the form which you once left for me and on which [your] signature was confirmed by the police with great difficulty.

Tanja [Tolstaya’s sister] is grateful for the nanny. Kuzminskij himself will send her the money; he left today for Moscow. Tanja didn’t hesitate for a moment. She’s overjoyed and has decided to take her at once. Poor Tanja has a very bad toothache and Mamà has started to feel better at our place. It’s hot, sweltering and windy here. The children still go bathing and Knertser has said I should take daily bran-baths. He says my rash is the result of fever and was bound to show up sooner or later. He was quite happy to give me the certificate, saying that you did just the right thing by going for koumiss. He kept saying time and again how helpful it would be for you, since apparently you have become much weaker both physically and emotionally.

And your friends Fet and Urusov are both convinced that you are suffering from your Greek [studies], and I agree with them that this is one of the main causes. Under separate cover I shall send you their two letters to me; read them and write to them from the kibitka [a small carriage]. I shall write them just a brief note, since I have very little time.

Now the walks and rides and games have ceased. All [available] forces, minds and hearts are concentrated on helping me in the nursery without a nanny. It’s all fairly easy to take with such precious helpers. Nanny, too, is suffering from fever and vomiting, she’s quite turned upside-down and probably won’t get well in under a week’s time.

I’m most grateful for the dish and the pas-de-géant. When everyone gets better, I’ll arrange with the Prince [Leonid Dmitrievich Obolenskij] to have it set up. He says we have to hire soldiers from the camp to set it up. For the building they bought wood260 for 450 silver roubles and took up all the space around the house with the thickest beams and boards. They’ll probably start construction soon. I moved Mamà into the study; here [in the nursery] the children didn’t let her have any sleep. I want to write everything down for you as quickly as possible, hence I’m not writing that coherently.

Farewell, dear friend, big hugs and kisses. I’ll be writing more soon, but right now there’s absolutely no more time. Live longer, get well, write more often and don’t worry about us.

Sonja.

I’ll write more another day. Nanny’s got up completely, only she’s [still] weak, and Lëvushka’s a lot better.

Nº 41 – LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY ![]() SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

[PSS 83/91]

23 June 1871. Karalyk.

I’m delighted to write you some good news about myself, dear friend — namely that two days after my last letter to you,261 where I complained about melancholy and ill health, I started feeling fine, and I feel ashamed for alarming you. I cannot, as usual, [bring myself to] write or say to you what I am not thinking. The only thing that upsets me is that tomorrow it will be two weeks since I left, and I have not received any word from you. I am overcome with horror, as I think about and vividly imagine you and the children and everything that could happen to you all.

As for my not receiving letters, nobody’s to blame — it’s just the location: 130 versts not covered by the postal service. Tomorrow it will be a week since the Bashkir messenger left; he was supposed to return on Sunday — today’s Wednesday, and he isn’t here.

Now I’ve learnt my new address, which I’ll append at the end. Write to me alternately: the first time to Samara, the second to the new address. When I receive the letters, I’ll write and tell you which address is better. —

The feelings of melancholy and indifference I was complaining about have passed; I feel I’ve entered a Scythian state of mind, where everything is interesting and new. I feel no dullness whatsoever, but [I do feel] the eternal fear along with your absence, which makes me count the days when my detached, incomplete existence will come to an end. For six weeks I shall endure from day to day, and so by the 5th of August (and I don’t dare talk or think [about it]) I think I shall be home. But what will [I find] at home? Will everybody be well, everyone just the same as I left them? You, most importantly. There’s a lot that’s new and interesting: the Bashkirs, who have a flavour of Herodotus, and Russian peasants, and villages, especially charming in their simplicity and kindness of the people. I bought a horse for 60 roubles and Stëpa and I are riding together. Stëpa’s a fine lad. Sometimes very enthusiastic and he keeps cursing Petersburg with a serious face; he can be annoying at times, and I feel sorry for him because in any case he’s bored and [I feel] sorry that he’s not at Yasnaya. Altogether, I have a great deal to tell you and I shall be annoyed if you listen to how Masha262 squeals and not to what I say. Is that going to happen? And when? I shoot ducks, and we eat them. Now we were out riding and hunting bustards, as usual, we just scared them off, and we were also hunting wolves and a Baskhkir caught a wolf cub. I am reading Greek, but very little. I don’t really feel like it. Nobody has described koumiss better than the peasant who told me the other day that we are feeding on grass, — like the horses. We don’t wish to harm ourselves in any way — not with intense activity, nor with smoking (Stëpa is weaning me from smoking and gives me now [only] twelve papirosas a day, decreasing the amount each day), nor with tea, nor with sitting [and talking] late into the night.

I get up at 6, at 7 o’clock I drink koumiss, and go to a winter hut [in the village of Karalyk] where [a number of] koumiss drinkers live. I shall talk with them, then I’ll come back and take tea with Stëpa, then read a bit, walk across the steppes wearing only my roubashka [long peasant shirt], keep drinking koumiss, eat a piece of fried mutton, and then we’ll go hunting either on foot or on horseback, and in the evening go to bed almost as soon as it gets dark.

You asked me to see what kind of comforts there are for life and travel. I’ve been asking around here about land, and they offered me some land here at 15 roubles per desjatina, which yields 6% [profit] without any trouble at all, and today a priest wrote me a letter about some land — 2500 desjatinas at 7 roubles per desjatina, which seems quite profitable. I’ll go have a look tomorrow.

And since it is very possible that I shall buy this piece of land, or another, I would ask you to send me a note issued by the Merchant Bank, which I might need for the down payment (with a money order through the Bank of Samara).

Here it is sleep that brings me the closest to you. These first few nights I dreamt about you, then about [our son] Serëzha. I am showing the children’s portrait to the Bashkirs here. How are Tanja and the nanny doing? Sasha has probably left.263 I regret that I did not speak with him before their separation, and that I didn’t tell him that even though we have had our differences, I am very glad that we parted good friends.

How is my standby, Ljubov’ Aleksandrovna, doing? I would gladly share my current state of health with her. What about the dear stallmaster264 and the girls? I remembered Varja yesterday upon seeing the herds of horses in the hills in the twilight. —

I dreamt that Serëzha was being mischievous and that I was angry with him; it’s probably just the opposite in reality.

Serëzha.

Write and tell me how you are getting on. Are you riding horseback and do Mamà and Hannah [Tarsey] curse or praise you often, and what [marks] have you gotten for [good] behaviour? Hugs and kisses.

Tanja!

There’s a boy here. He is four years old and his name is Azis. He’s chubby, round-faced and drinks koumiss, and is always laughing. Stëpa really likes him and gives him candy. This Azis walks around with no clothes. There’s a gentleman living with us who is very hungry, as he has nothing to eat except mutton. And this gentleman says it would be good to eat Azis — he’s so fatty. Write and tell me what [marks] you’ve been getting on your behaviour. Hugs and kisses.

Iljusha!

Ask Serëzha to read to you what I write.

Today a Bashkir went riding and saw three wolves. And he wasn’t afraid of anything and leapt from his horse right onto the wolves. They started biting him. He let two of them get away, but caught one of them and brought it to us. Tonight, maybe that wolf’s mother will come. And then we’ll shoot it. Hugs and kisses. Give kisses from me to both Aunties [Tat’jana Aleksandrovna Ergol’skaja and Pelageja Il’inichna Jushkova] and Lëvochka, and Masha, and my regards to Hannah and Natal’ja Petrovna [Okhotnitskaja], and to your Nanny,265 and do go for walks to the village [Yasnaya] and tell Ivan’s children and his wife that Ivan266 is healthy and is talking with the Bashkirs in the Tatar language, and does a lot of shouting at them, but they aren’t afraid of him and laugh at him. —

Farewell, darling, hugs and kisses.

[My] address is not certain. Write to the old one. —

Nº 42 – LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY ![]() SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

[PSS 83/97]

16–17 July 1871. Karalyk. [Preceded by SAT’S Nº 4U, 24-25 June 1871]

It’s been a long time since I’ve written you, dear friend. I’m somewhat to blame, but mostly Fate. I let one opportunity to write slip by, and since then every day I’ve been promised “[the post] is leaving, it’s leaving”, and I kept putting it off, five days, but now I can no longer brook [the delay] and am sending [this letter by] special messenger. My last letter to you, it seems, was on the 10th or the 9th before I left. We’ve actually started our journey: Kostin’ka267 (as he is called) [and] Baron Bistrom,268 a [Russian-]German youth who’s just finished a course at the lycée with honours, Stëpa and I — [we’re all] travelling in [something that looks like] a wicker basket (that’s how everyone travels here), [pulled] by a pair of horses without a guide or a coachman. We didn’t know ourselves where we were going, and we’d ask people we met along the road whether they knew where we were going. We were actually searching for places where there was koumiss, and where we could hunt, with only the foggiest notion of any [rivers named] Irgiz or Kamelik [tributaries of the Volga]. Our trip lasted four days and turned out splendidly. There was such an abundance of game that there was nowhere to store it — even nobody to eat [all those] ducks — and the Bashkirs, and the places we saw, and our companions were splendid.

Thanks to my title of Count and my previous acquaintance with Stolypin,269 all the Bashkirs know me here and have great respect for me. They received us everywhere with a hospitality that defies description. Wherever we go, the host will cook a plump and juicy mutton, set forth a huge vat of koumiss, roll out rugs and pillows on the floor, seat his guests down on them and not let them go until they have eaten his mutton and drunk his koumiss. [According to a local custom,] he gives his guests drink from his own hands and with his hands (no fork) stuffs pieces of mutton and fat into their mouths, and one cannot insult him [by refusing]. —

A lot that happened was funny. Kostin’ka and I ate and drank with delight, and that was evidently to our advantage, but Stëpa and the Baron were funny and pitiful, especially the Baron. He wanted to keep up with the others, and he drank, but towards the end he vomited on the carpets, and later, on the journey home, when we hinted that we might stop in once more to see our hospitable Bashkir, he all but pleaded through tears not to. From this you can see how healthy I am. My side hurt a little during this time, but only slightly, and it’s completely better now. The main thing is that there is no trace of the melancholy, and that now I’ve had my fill of koumiss and am now in a real koumiss state — i.e. from morning to night I’m slightly drunk on koumiss, and sometimes go for whole days without eating or eating very little. The weather here is marvellous. During our trip it rained; but for three days now the heat has been something terrible, but I like it. Stëpa is no longer bored, and it seems he’s filled out a bit and matured. I’d like to bring a lot of people here. You, [little] Serëzha, Hannah. I’m really bothered by her illness. God forbid she should break out again like last summer. Ever since you wrote me about [Aleksandr Nikolaevich] Bibikov, I’ve been keeping an eye out for him on the road. If he came, I would be very happy and treat him to all that he loves, and would probably undertake a trip to Ufa (staying with the Bashkirs en route), 400 versts, and from there I’d come back by steamship along the Bela River to the Kama, and from the Kama to the Volga. At the moment I shall almost certainly not take this trip, even though I dream about it. I’m afraid it would delay my arrival home by a day at least. Each day I am apart from you I think of you with more urgency, alarm and passion, and it is harder and harder for me. It’s indescribable. We still have 16 more days. But the trip to Ufa is interesting because the road to Ufa winds through one of the most remote and richest corners of Russia. You can imagine the land — the forests, steppes and rivers; there are streams everywhere, and the land has been [covered with] feather-grass, untouched since the creation of the world, yielding the best wheat. And [this] land — only 100 versts from a steamship route — is being sold by the Bashkirs for 3 roubles a desjatina. If not to buy, I would at least like to take a look at this land. My plans for purchase aren’t going anywhere [at the moment]. I wrote Sasha270 in Petersburg, asking him to deal with Tuchkov,271 and to Tuchkov’s local agent in Samara, but I haven’t yet heard from either one. I overheard rumours that they now want to ask upwards of 7 roubles [per desjatina]. If that is the case, I shan’t buy. You know that in everything I leave the decision up to Fate. So too in this.

After my last letter, I received two more letters from you. I wanted to write [you], darling, [and ask you to] write more often and [tell me] more, but the only way you’ll be able to get a reply to this letter of mine is through Nizhnij [Novgorod]. Still, your letters are probably more dangerous to me than all the Greek [writers] because of the excitement they arouse in me. Especially since I receive them suddenly. I can’t read them without [breaking into] tears; I tremble all over, and my heart beats [fast]. And you write whatever comes into your head, while for me every word is significant; I read all of them over and over. Two things you write about are very sad: the fact that I shan’t see Mamà unless I go to Liza’s and bring her to our place again, which I am planning to do, and, more importantly, that my dear friend Tanja is threatening to leave [Yasnaya Polyana] before I get there.272 That would be sad indeed. Why don’t you write about Auntie Tat’jana Aleksandrovna [Ergol’skaja]? I also received a letter each from Urusov and Fet and shall send a reply. As to Offenberg’s273 letter, I haven’t any idea yet of how to respond, but there’s no point in hurrying, since his address in Warsaw is good only until the 18th. But I want to answer as follows: to offer him the 90,000 [roubles] he is asking for, but only in instalments, without interest, over 2 ½ [or] 3 years, at 30,000 a year.

Big hugs and kisses to sweet Liza274 from you and me, and [ask] her not to get angry if in this heat and being constantly drunk [from koumiss], I don’t manage to reply to her letter which gave me such tremendous pleasure. — Hugs and kisses to all, even to Dmitrij Alekseevich,275 if he is there with his family, and regardless of whether he is teasing you or Tanja. Comfort Tanja. If her husband is good, and [I’m certain] he is, the unavoidable separation will result in nothing except that they will have a greater affection and a stronger love [for each other], and along with a slight love-sickness, which the wife ought to find pleasing. There is far less [danger] of unfaithfulness when they are separated than when they are together, since people who are separated cling to the ideal in their soul, which nothing can be compared to. This all concerns you, too. [Ask] Varja [Varja Valer’janovna Tolstaja] to write to me. Stëpa and I will have a lot to say in return. I’m glad that the pas-de-géant is up, but I have no clear picture how that all works for everyone. I can only picture Il’ja falling.

Oh, if only God would grant that everything goes along fine without me right to the end, the way it has according to your latest letters. Farewell, my precious dove, a big hug from me. And all my nerves are shot. Now I just feel like crying, I love you so much.

16 July.

17 July, evening. P.S. My health is perfect. I’m counting the days. The Bashkir hasn’t brought any letters from you. They didn’t give him any, because Jean [servant Ivan Vasil’evich Suvorov] is too assiduous and wrote a foolish note to the post office. I am hoping [there will be some] tomorrow.

Nº 43 – SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA ![]() LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY

LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY

[LSA 39]

27 July 1871. Evening. [Yasnaya Polyana]

I don’t know why you asked me to write [to you] on the 27th and 28th in Moscow.276 Does that mean you’ll be in Moscow by the 1st [of August]? I want to believe and at the same time I don’t; I feel happy and at the same time frightened, and don’t know myself what I feel when I think about you and our meeting. Lately I haven’t been able to think of anything else but your arrival; nothing interests me, and when I think about this and the children come by, I tell them Papà will soon be here, and I kiss them with delight, and they understand, and they themselves say every morning that now there are only twelve (or ten) days left. We are all expecting you on the 5th of August. But it’s not very nice when you don’t tell us when you set out. Does that mean I shan’t meet you at the station? I’d be glad to go to Tula if I could see you a whole hour earlier. Now I’ve been following your whole trip in [the railway timetable] Parovoz and, if you left Samara on the 2nd, you could be home by the 5th. I’m so afraid to expect you any earlier. For that matter, I’m afraid of everything: the steamships, and the state of your health, and your impatience to get home; I’m afraid that you might have drunk too little koumiss, and that I failed to persuade you [to continue your treatment and] not to hurry home. But lately I haven’t been strong enough to keep on persuading you not to [hasten] home. I am plagued day and night by my concern for you.

Your latest letter277 I received the day before yesterday. I read it at the Kozlovka station by lamplight while I was seeing off the D’jakovs. I was given this letter by [our cook] Semën, who was completely drunk at the time we were getting into the carriage to drive to Kozlovka, and as the road was dark and bumpy, I was on pins and needles all the way to the station, I was so anxious. This letter made me frightfully happy to know that you missed me so much, and from the anticipation of seeing you. I wrote you278 about D’jakov’s missing belongings; they haven’t been found, though some of the workers were suspected [of stealing them].

Everyone’s terribly interfering with my getting any [letter-]writing done: [My sister] Tanja is sitting right beside me (we’re all in the drawing-room) along with Liza and Varja — they’re sewing, reading and writing. Tanja and Varja are talking about the servants travelling [with Tanja] to Kutais. Almost nobody’s agreed [to go to Kutais] yet, except for Nanny and Trifovna.279 Leonid [Obolenskij], too, has come down with cholerine; he’s lying in the study, he has a fever, had a bout of vomiting and strong stomach pains. He’s better now, and he’s taken some bouillon for the first time. This cholerine makes me terribly frightened for you, too. After the koumiss [treatment], you should be on the strictest of diets. For God’s sake take care of your health, don’t eat any fruit or anything raw. We’re all very careful here, and we’re all quite healthy, except for Lëlja and Varja,280 who are both coughing; still they go out walking and run around the pas-de-géant. Lëlja does not go out alone, of course, but with me or Hannah, and I hope this, too, will be over by the time you get home. It strikes me funny that you will be reading this letter in Moscow just a few hours before we meet, but right now it seems like it will be an eternity before that happy moment arrives.

Tanja very often receives letters from her husband, and such tender letters I would not have expected from him. He writes that his only comfort is arranging and thinking about [future] conveniences for Tanja and the children, and says that he thinks about and loves her far more than the children.

This past night Tanja was tormented by a toothache and suddenly at 5 o’clock this morning she became very restless [and wanted] to go to Tula. She went with Verochka,281 stopping over with Marija Ivanovna,282 [then] went to see Vigand283 and [got treatment for] a tooth. Now she’s revived, but still very weak and sleepy. These days I’ve been staying pretty much at home — I don’t go out for walks, I don’t run around the pas-de-géant. I sit, work, read, and make little Masha [the Tolstoys’ fifth child Marija L’vovna] jump up and down. She doesn’t like me because I make her suck on my breast, and she continues to feed unwillingly, as there is not much milk at all. I’ve been moving about so much to keep from being bored that all my energy has dissipated — I sit and wait for you, and the only thing [I can do] is go over the details [in my mind] about you and your arrival. I can only delight and take comfort in the thought that I shall be seeing you soon. I’m no longer eager or happy to write to you any more, whereas before this was my comfort and joy. I’m so tired of waiting, of worrying, thinking about you and missing you. I keep dreaming that you are wiring me as to when you are coming, and that I’ll have the opportunity of going out to greet you. Farewell, my sweet. I probably shan’t write you any more letters now [as you will be home soon]. Still, if I don’t receive any news from you by the evening of the 30th [of July], on the 31st I’ll send one more letter to you at Moscow. Hugs and kisses for the last time in written form; soon I’ll be embracing you in person, and I shall see and kiss your sweet eyes, which I now picture as smiling and kind and excited.

Your Sonja.

Hugs from Liza, Varja and Tanja and kisses from the first two.

Nº 44 – LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY ![]() SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

[PSS 83/102]

14 July 1872. Farmstead at Tananyk.

13th.

I am writing from the [Tananyk] farmstead. I arrived safely, along with Timrot.284 Rumours of a decent harvest were not justified. Very bad. I haven’t yet seen all the fields; but [judging] by what I have seen and heard, I doubt what’s lost can be made up for, especially since the same amount will have to be sown again. It has to be sown, since after two bad years one can only expect some good ones, and to stop now would be pointless. Timrot wrote about what he saw in the spring, and then disaster happened on a scale not [even] the old people could remember; both the grass and the wheat were burnt by the heat, the ground was black, and the people started to move away for fear of famine. Today everyone cannot appreciate too much the blessing that there is grass and wheat to some extent. From the financial point of view, this is how our Samara affairs stand: We shall have to give Timrot between 2,000 and 3,000 [roubles] for the harvest and ploughing for next year and we must hope that once he sells his wheat he will send me back between two and three thousand, and, in addition, set up the farmstead on a firm enough footing so that next year we may come and find a wholly self-sufficient estate.

This has been an unfortunate year, but despite this misfortune, one can say that the Samara lands will yield 8% [profit]. One can say 8% since, even though no money will be forthcoming, the management of the farmstead is already costing no less than 2,000 [roubles]. The lease for hay-cutting brings in 670 roubles. Anyway, I can’t explain everything in a letter. I’ll tell you [now] about the farmstead itself and the house. The place is not at Tananyk [proper], but on the grounds of an old farmstead; it’s very good from the management point of view, and a very cheerful place. My first impression — and one you’ll probably share — was very pleasant, despite the fact that there is still no water in the pond.

The house is old (not so nice) and greyish-looking; but it seems that it will suit us perfectly well. It doesn’t have any partitioning walls yet, just two large rooms, and I’ve drawn up a partition plan, which I am sending you. Apart from that, there is a huge kitchen all ready for the foreman and the workers, and a kitchen will be built for us besides. Apart from that, [there is] a cellar, a larder and a small storehouse. These are all made of mud brick with an earthen floor. — Apart from that, on one side of the farmstead there is a huge barn. All this is just about ready. —

There are 5 horses and a ‘wicker basket’,285 and I am arranging to buy cows, sheep, yokes, chickens, etc.

Timrot is a very honest fellow, but, it seems, has been rather tight for money (he built a house in the town), and the accounts for my estate have got mixed in with his; he told me so himself. And [he says] that the balance of the accounts is now such that the amount he owes me is not that much. He is no doubt an honest man, but I find him quite repulsive, along with his whole family, and while his involvement in my affairs is very useful, it’s [all] quite repulsive. The deed286 and receiving-order have been ready for some time now, but not put into effect, since the 450 roubles of land taxes have not been paid. — About myself. We arrived at Timrot’s Wednesday evening. I stopped overnight with him and left with him yesterday to come here, and the first night I got a good night’s sleep. I sent to the Bashkirs for some koumiss, and so my material needs in respect to koumiss are thus taken care of. Today my friend, a peasant named Vasilij Nikitych, arrived from Gavrilovka, which is visible from the farmstead, about 6 versts distant, and brought chickens, milk and eggs. [Right now] the rain is pouring down in a torrent, and I’m waiting out [the storm] so I can ride over to Timrot’s. Today he is travelling to Samara, and I’ll have a talk with him about everything and send off [this] letter. The main thing is that the wheat which is still [growing in the fields] will not mature soon, and in any case it’s not a pretty picture, and so tomorrow I’m just going to look over the fields, select sites for sowing, take a ride over to one [other] plot for sale and have a look. If there’s money to buy it, I’ll be coming home a lot earlier than I expected. In my next letter I’ll tell you specifically when I’ll be home, but I can’t yet, because this is something I’ve made up my mind on just now, and I haven’t yet seen the fields or talked with Timrot.

As far as my bodily health is concerned, I can tell you that nothing ails me, and that I have borne the journey superbly; as to my mental state — of course it’s awkward, incomplete, and I’m virtually asleep. I don’t allow myself to think. The farmstead is home to the foreman — a young bachelor lad and a soldier. All around are people hay-cutting and ploughing. Timofej287 is very useful and dear to me. —

I could easily stay here four weeks if Petja [Tolstaya’s brother Pëtr Andreevich Behrs] were with me, as I would comfort myself with the thought that it would useful for him; and truly, the air here — you won’t understand if you haven’t tried it yourself. But [to stay here] all by myself — while it wouldn’t be exactly boring, it would be shameful to waste part of one’s happy and useful life on trifles. But to work without you — without knowing you’re right here — that’s something, it seems, I can’t do. Tell Stëpa [Stepan Andreevich Behrs] — what a tragedy! — Vasilij Nikitych’s precious little granddaughter Sasha, has died from measles.

Farewell, darling. I’ll write you [again] in three days. And I’ll wire you when I leave. —

Hugs and kisses to the children and our whole family.

Nº 45 – SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA ![]() LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY

LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY

[LSA 42]

[4 September 1876. Yasnaya Polyana]

My dear sweet Lëvochka, at the moment I’m on my way to see [my sister] Tanja off [to Kutais with her family], and even though everything here is in a terrible bustle, I am still thinking of you and feel for you such tenderness that I wanted at least to write a line or two. The whole morning we’ve spent packing and running about; not only that but the whole house is being washed and cleaned up, and Lëlja’s cough, too, is making me worry and fuss. It will all work out, things will calm down very soon, and then I’ll write you again. Right now my hand is trembling and I’m in a hurry. Last night I did a rough outline of an ordre du jour, and it seems fine. Tomorrow I’ll clarify further, and on Monday we’ll begin our studies. Stëpa’s still working on his kite. Last night he and I sat around and chatted until 2 in the morning, Tanja went to bed early. Today you’re on the steamer;288 our weather is warm today, with moments of clear sky.

[Neighbour Aleksandr Nikolaevich] Bibikov289 himself brought over two series today and had dinner at our place, and at the moment is still sitting with Stëpa. Trifovna [Stepanida Trifonovna Ivanova, the Behrs family’s housekeeper, then helping Tolstaya at Yasnaya Polyana] is crying a lot over having to part from Tanja and her children; I comfort her, telling her I’ll come and see her in Moscow. My [hand]writing is terrible, but you’ll [be able to] read it and understand; you simply can’t imagine the noise here and how excited the children are before [Tanja’s] departure. I am full of cares and good intentions for my life from now on, but yesterday there were moments of tearful sorrow [when I realised] that I’m all alone, and that it will be difficult to teach [the children] and to live without either you or Tanja. But today I feel healthy and energetic. Take care, precious; don’t catch cold, don’t get angry, don’t worry about us. If it weren’t for Lëlja’s cough, we would all be healthy.

Stëpa and my Tanja are also going to see [my sister] Tanja off. What kind of spirits are you in, and how are you doing on the steamer? Does Nikolen’ka like the Volga? I think about you every moment and this makes me happy during this time [of separation]. The only thing bothering me is that mice are eating away at the roots of life, and that things won’t always be the way they are [now]. For some reason today I keep thinking about [Zhukovsky’s] tale of the Wise Man Kerim (1844). But that’s what happens when I am sad. Farewell, you’ll receive this letter on your return journey. Big hugs and kisses, regards to Nikolen’ka. Really, I’ve hardly ever written such incoherent letters.

Your Sonja.

Nº 46 – LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY ![]() SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

[PSS 83/115]

5 September 1876. Kazan’.

I am writing to you, dear friend, from Kazan’, on today, the 5th, at 11 o’clock at night, and not from the steamer, but from the city of Kazan’ itself, where we have come to stay overnight, since we lost a whole twenty-four hours because of the chaos aboard a Samolët steamer290 we had the misfortune to travel on — it got stuck in the shallows and broke down. You can’t imagine how annoying this has been, when one is counting every minute, as I [am doing] now for you and even more for myself. The trip down the Volga was unpleasant enough up until now — the stuffiness and the [mainly] tradesmen passengers. Anyway, I did find several interesting and even extremely interesting people, including the merchant Deev,291 who owns 100,000 desjatinas of land; I am sitting with him at the moment in a hotel room, while Nikolen’ka has gone with a man from [the Khanate of] Khiva to a Kazan’ theatre. There was also a Tatar [who was] a priest. —

The weather here is magnificent, and my health is good. You are probably riding out to collect mushrooms. Please, don’t ride Sharik.292

I’ll be writing you from Samara about my plans for Orenburg. I should enjoy visiting Orenburg as that fellow Deev is from there and will help me buy some horses. I’d also like to see Kryzhanovskij293 there. In any case I shall try not to go beyond my 14-day schedule. —

Kazan’ awakens in me memories of unpleasant sorrow.294 Oh, I only hope you and the children — especially you — are healthy and at peace. Hugs and kisses to you, my darling dove, and to the children and my greetings to both Sofesh,295 if she is there, and Mr. Rey.296 —

Yours, L.

It seems I very much feel like writing.297

On the envelope: Tula. Her Ladyship Countess Sofia Andreevna Tolstaya.

Nº 47 – SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA ![]() LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY

LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY

[LSA 45]

15 [January 1877]. Saturday evening [St. Petersburg.]

My dearest Lëvochka, here I am writing you from Mamà’s and I still haven’t quite figured out how I got here so quickly and ended up in Petersburg.298 On [the train] to Moscow I sat with some elderly woman, the wife of a Saratov landowner, talking all the time with her and her daughter, and reading without getting tired. [At the Kursk Station] in Moscow I was met by Istomin,299 and he and I, along with Stëpa [Stepan Andreevich Behrs], [stayed] in the railway carriage [as far as the Nikolaevsky Station, where I] transferred to the Nikolaevsky Express.300 There [at the station] I was met [first] by Serëzha, and later by my Uncle Kostja,301 — he’s so splendid, it’s practically a shame; he’s off somewhere for the evening.

Serëzha reacted rather strangely to meeting Uncle, and kept staring at him intently, but it all worked out; we sat there for a whole hour, drinking tea over a cheerful chat. Then we spent quite a while looking for a place for me — the whole [train] was full — and finally found a compartment with two benches, where some lady was seated. At this point Uncle Kostja brought Katkov302 over to see me. We talked, he was taking the same train to Petersburg for five days. The lady turned out to be very respectable; she was from Orlov, wealthy, a landowner’s wife whose maiden name was Obukhova. I talked with her a lot about literature. She was enthusiastic — and quite intelligently so — about your works. In fact, she told me a great deal: she is very well-travelled — both abroad, and to Petersburg, and all over Russia. Later we both lay down on our respective benches and had quite a good sleep, despite the same perspiration, the same melancholy and coughing, though the coughing wasn’t as bad [as before].

In the morning Katkov dropped by twice to ask me had I slept well and did I need anything. I thanked him and enquired in return, saying that it was hot [in the carriage] along with some other remark. Then Stëpa and I went to see Mamà. She was still in bed, expressing through tears her joy upon seeing me. She was distressed that [my sister] Tanja wasn’t there, but she wasn’t as upset as I had expected. Stëpa went to see Strakhov,303 while Mamà and I chatted away; she is very advanced in years and is constantly in ill health. And she kept repeating: “I’m so happy to see you! So happy!” Strakhov was at Botkin’s;304 he was talking about me, and gave [the doctor] my visiting card, and Botkin wrote on my card:

“If the Countess drives out, I shall be at her service on Monday, Wednesday and Friday from 8 p.m. on. If the Countess wishes me to visit her at her home, please give me the address and then I shall arrange a day and time for an appointment.”

Today I wrote Botkin a note saying I had arrived [in Petersburg], and thanking him for his agreeing to come and see me. I asked him to name a time when he was free. He replied that he could come tomorrow between 3 and 5. Mamà and Stëpa, as well as Petja [Tolstaya’s brother], had all advised me to invite Botkin to the house, and not go to him myself. Mamà assures me that I might waste 4 or 5 hours at Botkin’s, [which would be] indecent and unbearable. And Botkin, it seems, does not do a good job of treating patients who come to him, since he has little time to see 60 people. And Stëpa says that you’ll be glad that I invited him over, even though it costs more.

Petja came for lunch with us, along with his wife and daughter.305 She’s really very sweet, his wife, and they are most touching with their dear little daughter and their poverty. Petja would very much like to find some means of getting out of his dismal situation, even if it means taking the first available job so as not to build up further debts. Vjacheslav306 was dressed in a frock coat. He is extremely well-mannered, but is thin and pale. He is in a class equivalent to Grade 5 at a gymnasium.

Liza307 appeared just before [going to] the opera in a magnificent silk outfit with diamonds on her head and everywhere — some sort of stars like Polina’s,308 and plump — horrors!

While Petja was giving his little daughter a drink of milk, he managed to spill some on her dress. She jumped up, shouting: “Stupid! Fool!” etc. [Her] arrogance is amazing. Yes, I agree with you: [it’s better to keep] as far away from her as possible. Tomorrow I’m going to see Alexandrine,309 and somewhere else besides, if I can do it by three o’clock. I’ll be seeing Alexandrine between two and three. In the evening I’ll stay once again with Mamà and Petja and Stëpa. I’ll drop around to see all my relatives for a minute. All-in-all, nothing yet is clear to me [at the moment]; today I didn’t even step outside the house; I stayed the whole day with Mamà and I feel comfortable with her. I keep remembering you all, my dear ones, but I try not to think too much and not to get upset. I’m afraid that at night I shall feel this great longing for you all, and that I’ll imagine all sorts of horrors. But in telling Mamà about my family, about you and the children, it’s just like I’m coming home again and I like talking about you all. Thank my dear [sister] Tanja — she always cares about everything — for the pears. I ate them with delight along the way when my mouth was dry.

Your Anna Karenina (the December [instalment]) was praised to the skies in Golos and Novoe vremja.310 I haven’t read them yet; I’ll bring them along, if I can. Mamà, Stëpa and Slavochka told me [about them]. Lëvochka, my precious dove, take care of yourself and the children. A hundred hugs and kisses to you, and Serëzha, and Tanja, and Iljusha, and Lëlja, and Masha.311 I’ll definitely arrive [home] Wednesday evening.

Yours, Sonja.

Nº 48 – LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY ![]() SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

[PSS 83/122]

16 January 1877. Yasnaya Polyana.

As you can see, everything here is going along fine. — Yesterday I taught Lëlja and Tanja, and Tanja got me so angry that I yelled at her, for which I am quite ashamed of myself. I can’t get any work done. Last night the children sat with me and did some colouring, and I played chess with Vladimir Ivanovich,312 and later played the piano until one o’clock [in the morning]. Even then I couldn’t get to sleep for a long time and awoke early. Now I’m off to the station. The children went skating, but right now we have a severe frost; overnight it was 19 degrees [below zero], but [today] in the sunshine it’s plus 5. —

The most boring part of life for me is taking meals with teachers constantly sniping at each other.313 Every minute I think of you and try to imagine what you are doing. And it always seems to me that even though I’m depressed (on account of my stomach), that everything will be all right.

Please don’t hurry [home]. Besides, even though you said you wouldn’t be buying anything, don’t think about the money, and if you take it into your head to buy something, borrow the money from [your mother] Ljubov’ Aleksandrovna and go shopping, have fun. — After all, we’ll pay her back in three days.

Farewell, darling. I still haven’t received any letters from you. I try not to think of you while you’re away. Yesterday I went over to your desk and jumped back as though I had burnt my fingers, so as to avoid picturing you so vividly. Same thing at night-time — I don’t look at your side [of the bed]. As long as you are in a strong, vigorous spirit for the duration of your stay, then everything will be fine.

Please give my greetings to everyone, especially Ljubov’ Aleksandrovna.

On the envelope: Petersburg. Èrtelev Lane, House Nº 7, Apt Nº 1. Countess S. A. Tolstaya, c/o Her Ladyship Ljubov’ Aleksandrovna Behrs.

Nº 49 – LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY ![]() SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

[PSS 83/125]

28 or 29 May 1877. Moscow. [Preceded by SAT’S Nº 5U, 28 May 1877]

I am writing to you from Ris’s,314 from his magnificent apartment and under the influence of his reassuring geniality. — Kostin’ka315 sent me [back] the original, and he himself came. Kostin’ka’s acid nature is unimaginably disturbing. He’s to blame for everything. I poured out all my anger to Ljubimov,316 whom I met in the railway carriage as we were coming into Moscow. But I didn’t get overly wrathful. I remembered ‘the spirit of patience and love’.317

I am publishing [Anna Karenina] as a separate book with Ris, without censorship, adding from previous [editions] whatever is needed to make up 10 printer’s sheets.318

Now it’s 2 o’clock, and I shan’t manage to leave today, but I’ll go at 4 o’clock tomorrow.

Stay completely calm, and, most importantly, healthy.

If I was annoyed, that’s all passed now.

Strakhov recommends publishing as a separate book.

Hugs and kisses, my darling.

Yours, L. Tolstoy.

I would desperately like to leave today.

Nº 50 – LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY ![]() SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

[PSS 83/127]

26 July 1877. Optina Pustyn’.

26th, evening.

I am writing to you, dear friend, from the Optina319 [Pustyn’ Monastery] hotel after a four-hour vigil.

We had a safe arrival thanks to Obolenskij.320 A magnificent four-seater carriage was waiting for us at the train. We were exhausted, but still arrived at 3 o’clock in the morning. This morning Dmitrij Obolenskij came and spent the whole morning with us, partially interfering. I barely managed to excuse myself, to avoid going to his place today, but tomorrow I shall go at 5 o’clock, spend the night there, and leave at dawn, to make it to Kaluga by 12 and to Tula by 5. I would ask you to send horses there for 5 o’clock on the 28th.

If I don’t arrive [then], have them come [later] the same day, for 11 [p.m.].

I might oversleep and be late. I am healthy, and in very good spirits.

I’m terribly disappointed that Sasha321 didn’t come with us. Only God grant that you’re healthy and not troubled by anything. Good-bye, darling. —

Nº 51 – LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY ![]() SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

[PSS 83/130]

9 February 1878. Moscow.

I was tormented the whole journey by the thought that I didn’t say good-bye to you properly and didn’t ask you to write to me.

My only [concern] is that you’re in good health. — Take care, be healthy and don’t worry. I arrived safely, talked with the old fellow Levashev322 the whole way. I spent the evening in our ‘nest’323 with Kostin’ka [i.e. Konstantin Aleksandrovich Islavin] and [Vladimir Konstantinovich] Istomin talking business — i.e. about books.324 He gave me a lot [of information]. Today I went to see two Decembrists,325 had dinner at the [English] club and in the evening I was at Bibikov’s,326 where Sof’ja Nikitichna327 told me and showed me a great deal.

Now I’ve been spending the rest of the evening at the [Dmitrij Alekseevich] D’jakovs’ with Mashen’ka [Marija Nikolaevna Tolstaja], Lizan’ka [Elizaveta Valer’janovna Obolenskaja] and Kolokol’tsova,328 and that’s where I’m writing from. Tomorrow I’ll go see the Decembrist Svistunov, have dinner at Istomin’s, and spend the evening with Vladimir.329

Hugs and kisses to you and the children. The time is passing terribly quickly — nothing gets done and one gets horribly tired.

This morning I was at a funeral service for the old man Perfil’ev.330

Tolstoy.

On the envelope: Tula. Her Ladyship Countess Sofia Andreevna Tolstaya.

Nº 52 – SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA ![]() LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY

LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY

[LSA 47]

[5 March 1878. Yasnaya Polyana].

I am very grateful to you, dear Lëvochka, for sending me the note from Tula,331 but to my concern over you was added another even stronger worry; you shouldn’t have gone; of course, it’s all finished now, and you are probably either in Petersburg or on your way there, but how did your journey end? Yesterday and today my little one332 was extremely restless on account of the snowstorm, and as I paced the children’s room in quiet, measured steps with the baby in my arms, I paid heart-stopping heed to the howling of the wind. This snowstorm has been blowing for three days now, and I imagine that the trains are delayed everywhere, and that you with your weak nerves and from the unfamiliarity [of the situation] are exhausted from your lengthy journey. And what made you feel you had to go? After all, you didn’t make it to Solovëv’s333 lecture, and you probably had a difficult journey. I shall wait impatiently for a letter from you from Moscow on Tuesday. And now you won’t be returning from Petersburg until Saturday at the earliest, otherwise you will have precious little time.

Everything here is always worse when you’re away. The children are acting up; Serëzha and Tanja ran out into this fearful storm wearing nothing but light frocks; I punished both of them and shut Serëzha up in your study and Tanja in Auntie’s room. Then they got into a fight; Il’ja and Lëlja threw paper darts at Serëzha; he got angry and struck them, and they struck back, — [then] they came to me in the nursery to complain. I naturally got very upset with them. After dinner Serëzha bashfully took my hand and said: “Don’t be upset, Mamà!” I told him: “Children, after dinner let’s all get along together — otherwise, what kind of Sunday is this?” Serëzha [then] went off to write his diary. Tanja, too, calmed down, but Il’ja, Lëlja and Masha were unrestrainable, they would hide under the bed, and would call out “Fool!”, and Mr. Nief334 even got depressed.

Before bedtime Il’ja and Lëlja came to see me in the nursery to apologise; they lay down on the sofa and kept repeating “What a boring day it’s been!”, to which I responded by giving them a lesson about conscience and pangs of conscience and said that unfortunately I would have to write Papà about their conduct. Lëlja said: “Also say that starting Monday we’ll behave ourselves all week long.”

I still have a fever condition; I’ve stopped following my Lenten fasting.335 Yesterday the German woman336 came by, saying that you sent her a fur coat, and Kurdjumov337 didn’t go on account of the snowstorm and a sore throat. Today Vasilij Ivanovich338 took a trip to Tula. Yesterday he and I talked a lot about spiritualism and all the children gathered around in a circle to listen.

I am very interested in your acquaintanceship and conversation with Pushchina.339 You will have a lot of interesting things to tell me. Farewell, dear friend, hugs and kisses to you and Mamà; I can’t wait to hear your news.

Sonja.

Nº 53 – LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY ![]() SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

[PSS 83/134]

7–8 March 1878. Petersburg.

I am writing to you once more in the evening time, dear friend, from Mamà’s. This morning I went to visit Aleksandra Andreevna,340 and stayed with her until 3 [o’clock]. From her place I went to see Bistrom.341 The terms [of his sale of land to me] are splendid. I pay 20,000 [roubles] now, the rest over two years at 6% [interest]. He’s very kind and accomodating. From there I went to have dinner with Vladimir [Aleksandrovich Islavin]. I played cards there until 8 [o’clock]. Then I went to see Praskov’ja Vasil’evna;342 I [stayed] there until nightfall, and [then] went home.

Yesterday I fell ill, but today I’m quite healthy. Tomorrow I’ll find out from the notary how and when I can draw up a bill of sale, and I’ll write [you about it].

I received your telegram [sent 7 March] last night and am not replying, since you will probably receive my letter faster than a telegram. I also received your letter.343 344 Pity that the children acted up so badly. If you don’t receive a telegram, don’t get upset, darling. —

All the Tolstoys have a sincere love for you and praise you, and I’m delighted. I shan’t stay even an extra hour beyond what is needed. It is boring and alarming here, though I feel very calm and settled.

Hugs and kisses to you and the children. Tell Andrjusha not to worry.

L.

On the envelope: Tula. Her Ladyship Countess Sofia Andreevna Tolstaya.

Nº 54 – LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY ![]() SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

[PSS 83/143]

14 June 1878. A steamer on the Volga.

14 June.

Dear Friend,

I’m writing from the steamship345 in the evening so that I can send [this letter] off early tomorrow morning in Kazan’. The children are sleeping soundly beside me and the whole day our trip has been calm, safe and, as always, not boring. [I have seen] some new and interesting faces, especially a professor from Helsinki on his way to study the idol-worshipping religion of the Mari — the only representatives of the Finnish peoples who have not converted to Christianity. Then there is a young man named Ermolov346 — he used to travel with us as a lycée student, but now as a soldier of the Chevalier Guard. Having heard my story,347 he offered [to lend] me some money, and I borrowed 50 roubles from him. With the same post I am writing to Moscow, asking Nagornov348 to send him and to the Samolët [steamship] office 50 and 60 roubles [respectively]. My chagrin and shame over losing the money has still not passed.

The children are very good, they converse with the ladies, as well as [other] boys their own age, and are not giving Mr. Nief and me too much trouble. Besides, Nief is assiduous as usual, kind-hearted and cheerful. We bought [walking-]sticks at Kuzmodem’jansk and have been buying berries through Sergej [Petrovich Arbuzov].

All the bustle and crowds of people are tedious and difficult to endure, and it’s as though I am unable to breathe spiritually. I shall breathe freely when we get to our destination, and then the usual pattern of feelings and thoughts will ensue.

Are you bored without me? Please don’t let yourself [be bored]. — I can just picture you — if, God forbid, you’re not in good spirits, — saying: “How can I help it? [How could you] go away, abandon me, etc.?” Or, better still, I picture you smiling as you read this. Please, do smile. —

Today is Serëzha’s exam. Please write and tell me what the headmaster349 says. I hope Serëzha, even if he doesn’t distinguish himself all that much, at least won’t fall flat on his face. Hugs and kisses to Tanja — I’m asking her not to walk bow-legged, not to forget to brush her teeth, and not to get thrown by hooks and buttons. Here on the ship the little girls are all very good about this. Hugs and kisses to the dear Geschwister Auntie Tanja and Stëpa350 and I am grateful to them for looking after you. I know.

Farewell, darling, hugs and kisses to you and Andrjusha. I have not forgotten — and am not forgetting — Masha.351 Love and kisses to her.

Yours, L. T.

On the envelope: Tula. Her Ladyship Countess Sofia Andreevna Tolstaya.

Nº 55 – SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA ![]() LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY

LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY

[LSA 53]

18 June 1878. 12 o’clock a.m. [Yasnaya Polyana].

It seems this is already the fifth letter that I’m writing to you, my dear Lëvochka, and every day I receive letters from you, to my great delight. Today I received the one you wrote on the steamship and despatched at Kazan’.352 Why are you still bothered about [the] money [you lost]? It’s neither here nor there, it’s time to forget about it, we’ll just earn more money and shan’t notice those 300 roubles.

I’m writing you this letter against a background of a loud argument between Stëpa and Tanja about the feeding and raising of children, and so I fear it will be an incoherent letter; still, I want to write in a little more detail.

Our grande nouvelle is that Nikolaj Nikolaevich Strakhov is with us. He arrived yesterday on the night train and was very surprised not to find you here. But, it seems, he is very happy that he came. Last night we talked about Samara, and somehow our conversation led to my giving him an invitation, and he will be coming to see us at the end of July at our farmstead,353 and [then] we’ll [all] come back together. Now he is on his way to see Fet.354 I still haven’t made up my mind whether I shall come [to see you] or not. These past three days my little one [Andrjusha] has not been well, but today, especially this evening, he has shown improvement; the weather has again been warm and delightful, and I am getting ready [to go] again. But, faithful to your rule — and mine, too — I keep repeating: “If God be willing!” I want to go see you as soon as I can, but then I look at Andrjusha’s thin little neck and sunken eyes of these past three days and think: “No, I shan’t go for anything!”

I’ll decide everything after I receive your telegram. The other day my little boy experienced a bad bout of vomiting and I became alarmed to the point of desperation, thinking this was another attack of brain disease. Then yesterday he had diarrhœa and, now that the warm weather has returned, he’s a lot better. I haven’t written you about his disease so as not to scare you, [being] so far away, and still not knowing the specific nature of his illness. Now, apparently, it’s because of his teeth, which are going to be coming out very soon; in the meantime God has shown mercy. Nikolaj Nikolaevich is delighting in Nature, he went swimming with Stëpa, Serëzha and Antosha,355 laughed with [my sister] Tanja, played croquet — he and Tanja against me and Vasilij Ivanovich [Alekseev], and we won, much to Tanja’s disappointment. The older children are behaving themselves well, pretending to be grown-ups. Serëzha sometimes even makes bold, but is quick to shy away if I shame him for that. The headmaster has told me nothing about his marks; rumour has it that he passed his exams, only with a ‘3 minus’ in Latin. — Today they did some horseback riding: Stëpa, Serëzha and Antosha went to see Aleksandr Grigor’evich,356 and gave him 66 roubles for lessons. Now I have 300 roubles and am waiting for a similar amount from Aleksej,357 [also] from Nagornov, but I hesitate to take and carry with me the 3500 roubles from Solovëv.358 How come you asked me: “Are you bored without me?” Do you actually have your doubts about that? But it’s not so much that I’m bored (there’s no time for boredom), as much as I worry terribly about you and the children [Il’ja and Lev], and, believe me, it takes every bit of my soul’s powers to keep from sometimes falling into a state of gloom and alarm. You can’t imagine what goes through my head! And we shan’t be seeing each other again all that soon. [I’m concerned about] how you’re settling in on the farmstead, whether you might have forgotten to buy supplies, having lost my note (a list of provisions for you) in your wallet?

Strakhov says to tell Iljusha that the things for collecting insects have been in Tula for some time, but he forgot to send the receipt and now they will be sending it. [The dogs] Dybochka and Korka are very happy, they were running and playing around the croquet pitch. I’m very glad that Lëlja was so easy to travel with; hugs and kisses to my precious boys, I think quite a lot about them. When I come to the farmstead, I hope they will have lots of interesting things to tell me. My regards to Mr. Nief. God grant we shall meet very soon, and that it will be possible for us to travel. Farewell, my dove; I am going to feed my boy who is calling out, and then to bed.

Sonja.

Tanja and Stëpa are very nice with me, and, of course, a great joy to me.

Nº 56 – LEV NIKOLAEVICH TOLSTOY ![]() SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

SOFIA ANDREEVNA TOLSTAYA

[PSS 83/145]

18 June 1878. Farmstead on the Mocha.

I am sending you two good letters from the boys.359 They wrote them cheerfully and enthusiastically. They were acting up because they were tired, but now they’re calm, cheerful and precious. I shall begin at the beginning — at the time I wrote my last letter, from the steamer, as we approached Samara. We disembarked before 8 [a.m.], hired drivers and went to buy groceries. We got everything done and made it to the train without hurrying. It leaves at ten minutes to ten.

We boarded a 3rd-class [carriage]. We had plenty of room on board and at 2 o’clock arrived safely at the Bogatovo station. Here we were met by [the Bashkir coachman] Lutaj with a coach. The coach really shows its age, but it is nevertheless solid and comfortable. We left at 3. We took turns sitting in the best seat, beside the coachman, and easily arrived at Zemljanki by 9 o’clock — it was still light. If there had been a moon out, we might have got to the farmstead before midnight. But since we didn’t know what condition [the estate] was in, and because it was dark out, we decided to spend the night at Truskov’s — a hospitable fellow. We all slept next door in the barn, but Mr. Nief and Lëlja suffered from fleas, and in his sleep Lëlja kept scratching himself and kicking me. We arrived [at the estate] in the morning, and I went straight to see Mukhamedsha,360 who had made his home here, too, a little distance away. They wanted to marry him off, and yesterday he asked my advice about that. Then I went to the house and, in planning out the rooms, I discovered that there will even be extra rooms [available]. Though, if you decide to come on the basis of the telegram I am sending you today, you won’t get this letter, but I’m sending you the plan and description in any case.

Here is the plan of the house, and my idea for the apportionment of the rooms. I’ve given a lot of thought to it, and this seems to be the best [choice]. And this is how I’ll set it up if I receive a telegram from you that you are coming. It’s quite clean and pretty warm; the floor has just a few holes here and there — I’ll have it taken care of — and there are even stoves. One is in the office part, one in [the main part of] the house. There are willow-bushes around the house itself and rather pitiful-looking gooseberry bushes, and there’s water right in front of the house. Just one drawback: the farmstead also includes a pit full of dung with flies, which won’t allow us to have dinner, or drink tea, or work [outside] except in the evenings.

I am drinking koumiss — I can’t say with any special pleasure, rather from habit; and I don’t have any particular desire to stay here over the summer. Mr. Nief is discouraged; evidently he doesn’t like it [here]. It’s good that there are lots of horses, and Bibikov361 has made us a fine carriage: it easily seats 9 people; it is low and safe. And if you should come, then every day after dinner I imagine we shall [all] take an excursion, some of us on horseback and some in the carriage.

Bibikov is splendid at looking after things. He won’t need money for the harvest. There are melon fields. The horses are very good. The wheat is very good, too. Much better than I had expected. I don’t do anything, I almost don’t do any thinking and I feel I’m in [some kind of] transitional state. I’m concerned about you, and think [about you] whenever I’m alone. Only God grant that everything may be safe during our time apart, and I love this feeling of special love, the very highest spiritual love toward you which I feel all the stronger when we’re apart. Now here’s the main question: should you come or not? Probably not, and this is the reason. I know that I am the principal [focus] in your life. I’d rather return [home] than stay here. I don’t believe in the benefits of koumiss for me. And since there is a drought here and [rumours about] diarrhœa are heard, [I am concerned] about the harmful effects it might have on you and [our youngest son] Andrej. As for major comforts, it’s hardly any better than before. — But don’t forget one thing: whether you decide to come or stay, and whether something happens outside our control, I shall never blame either one of us, even in my thoughts. It shall be God’s will in everything, except our foolish or good behaviour. Don’t get angry — the way you sometimes get upset when I mention God.362 I can’t stop myself from saying this, as it is the very basis of my thought. Hugs and kisses, my precious.

Hugs and kisses to the children and all our family.

If you do come, I’ll drive out and meet you at Zemljanki.

I forgot the most important thing: if you don’t come, we’ll be leaving on the 1st of July.

I-1. Sofia 1863

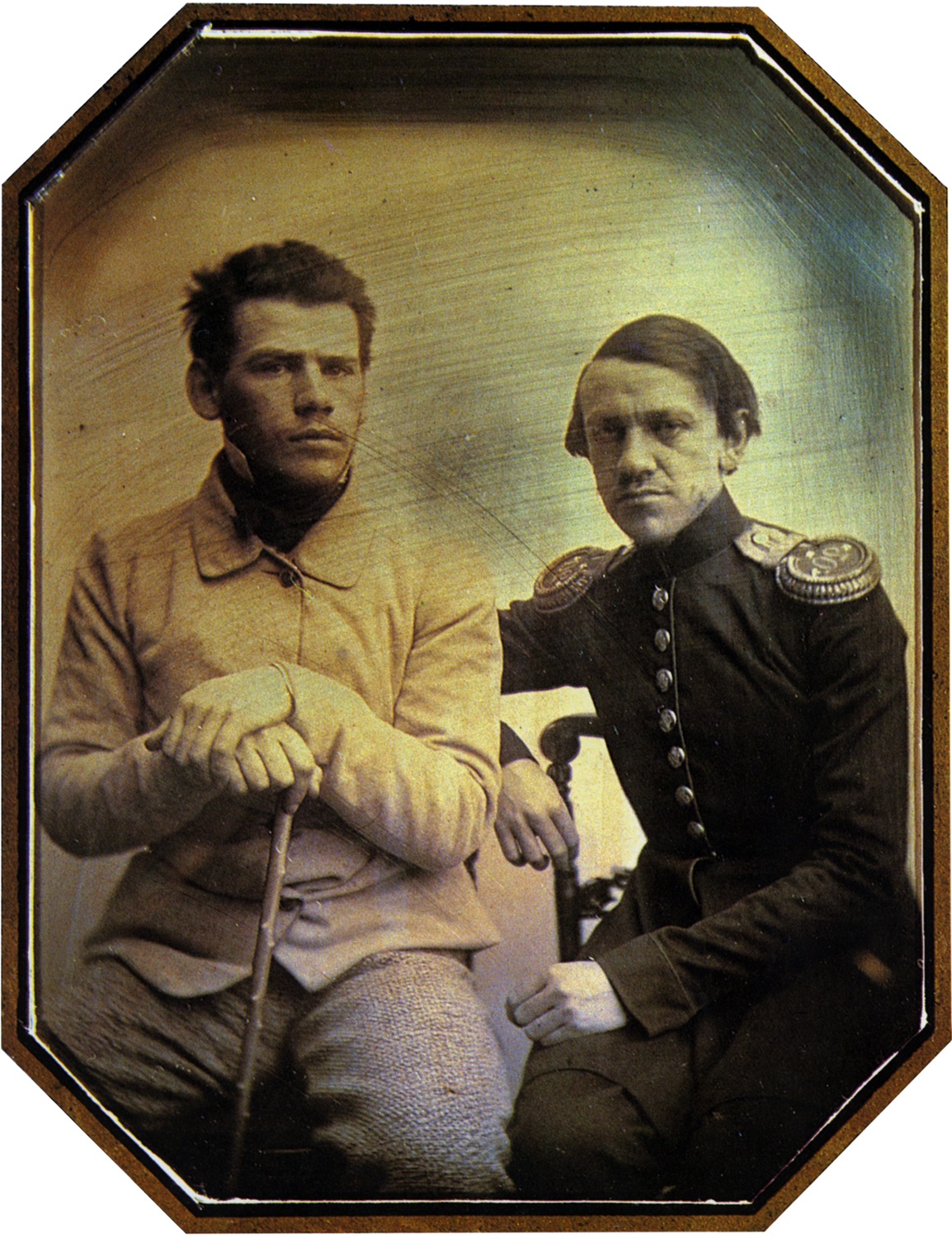

I-2. Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy and his brother Nikolaj Nikolaevich Tolstoj, 1851.

Daguerreotype by Karl Peter Mazer

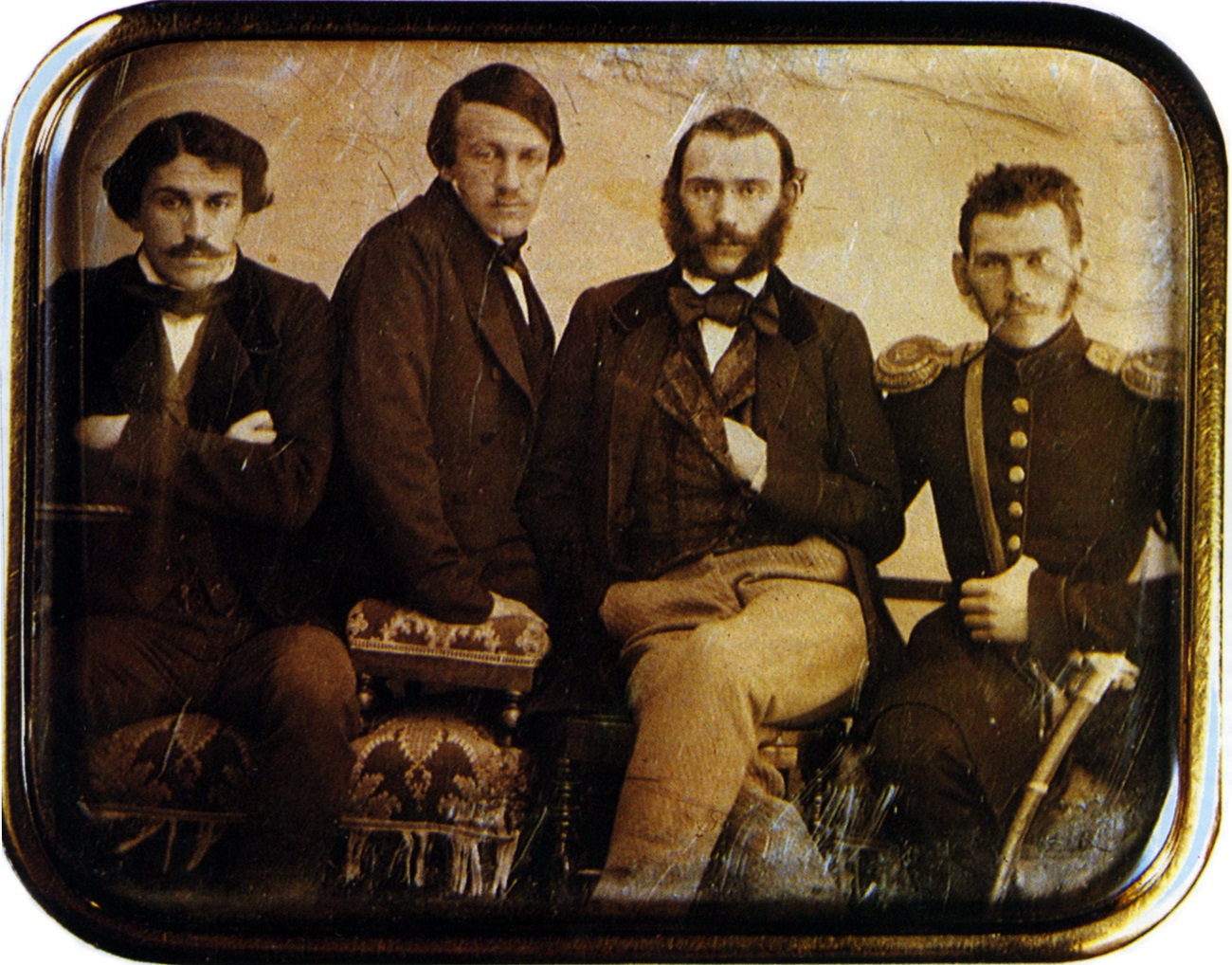

I-3. Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy (far right) and his three brothers (left to right) Sergej, Nikolaj and Dmitrij. Daguerreotype, 1854

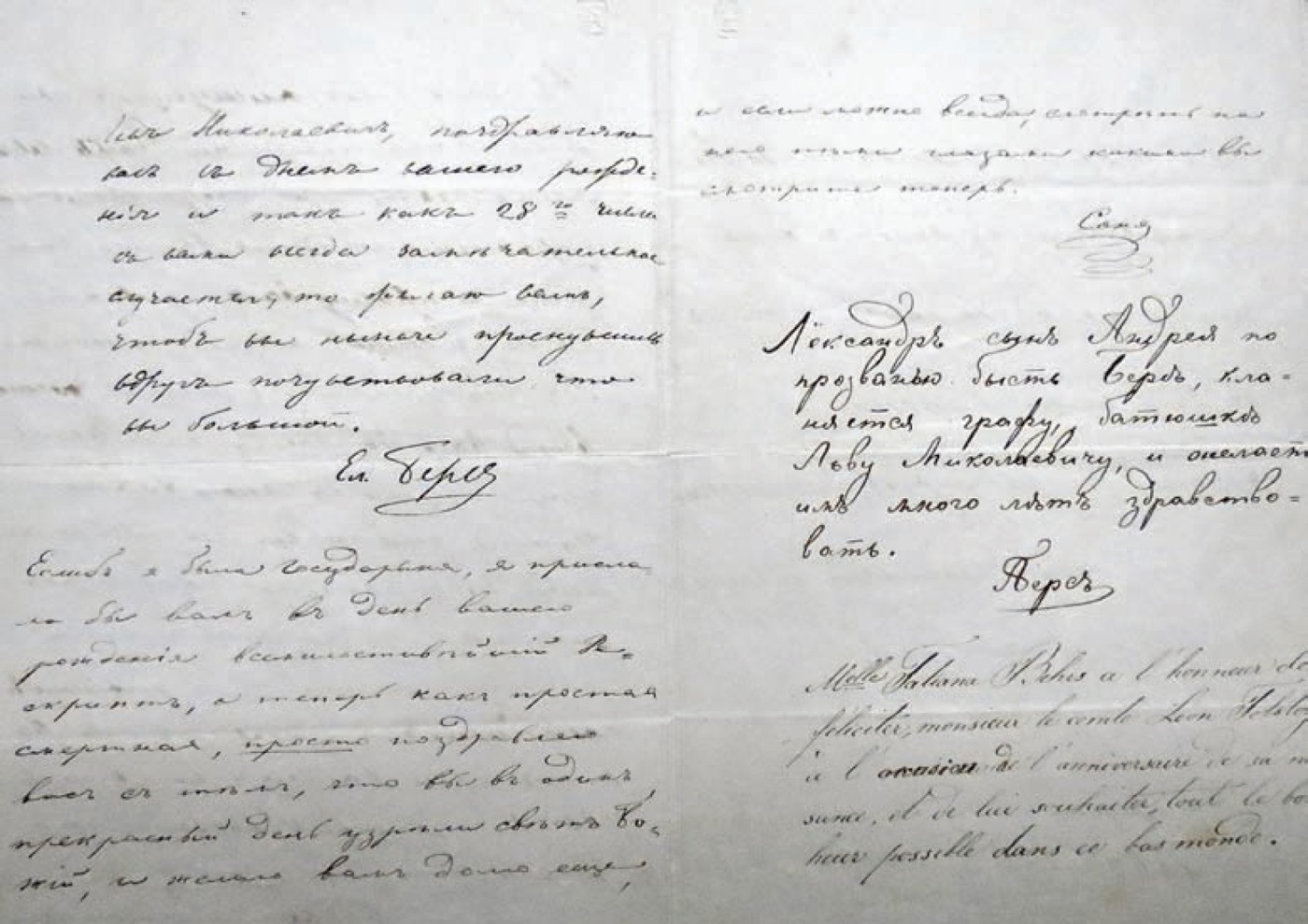

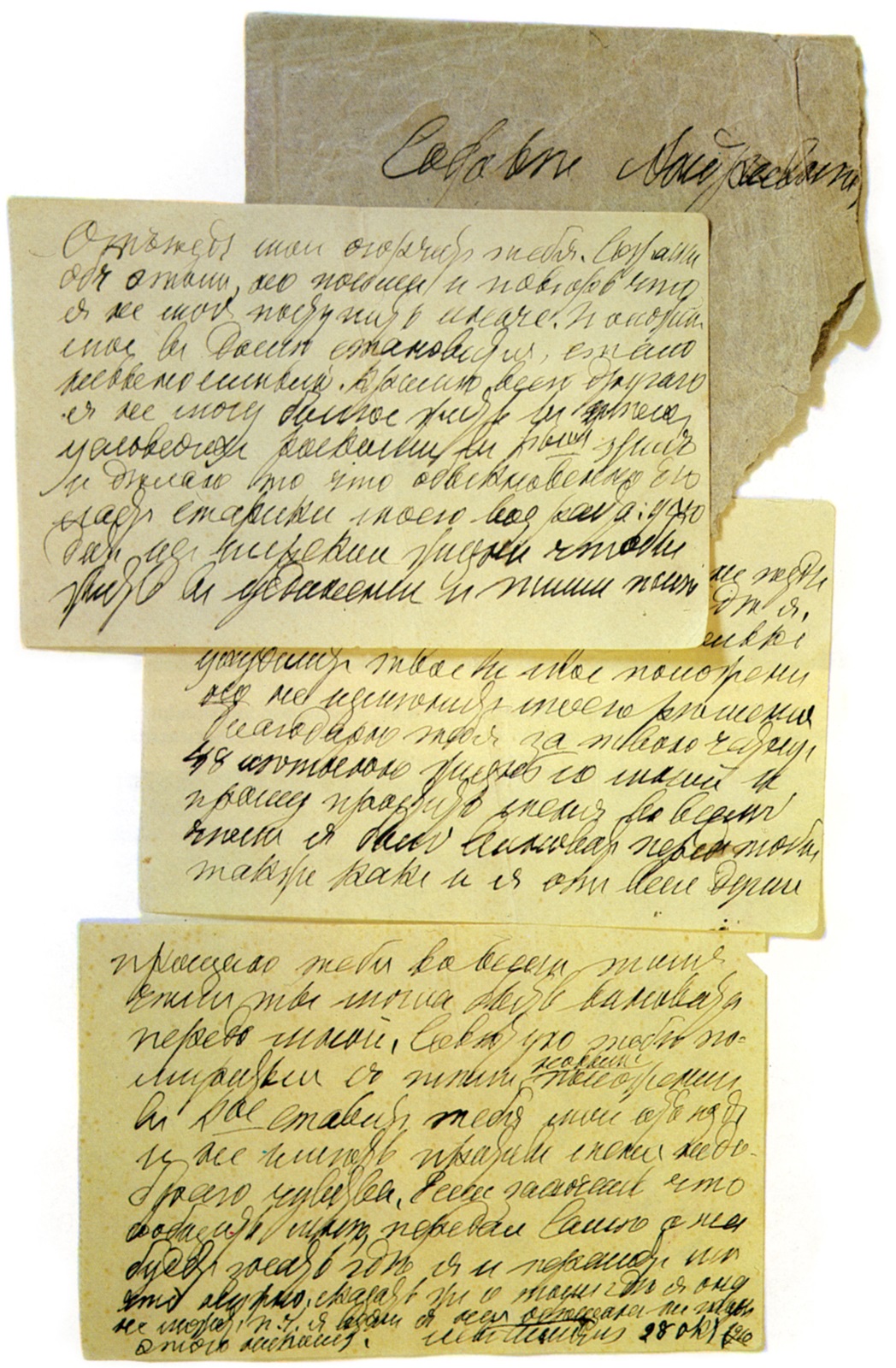

I-4. Letters from Sofia Andreevna Behrs and her siblings congratulating Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy on his 34th birthday, 28 August 1862, signed (in order): El[izaveta] Behrs, Sonja, A[leksandr] Behrs, Mlle Tatiana Behrs [note written in French]. The note from Sofia Andreevna (Sonja) appears as Letter N° 1 in the current volume.

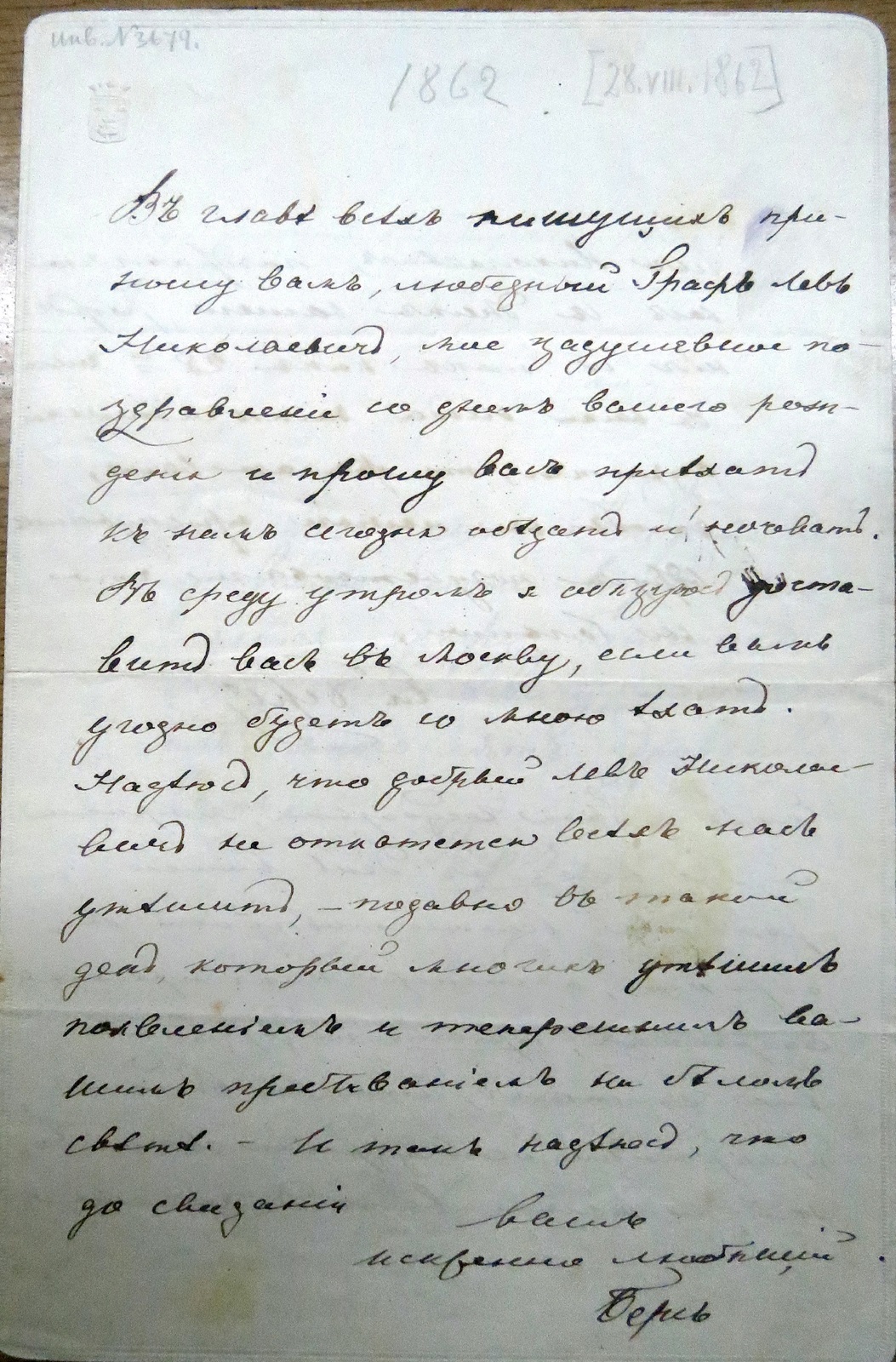

I-5. Congratulatory letter to Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy on his birthday (28 August 1862) from Sofia Behrs’ father, Andrej Evstaf’evich Behrs, inviting Tolstoy to take dinner with him and his family and to stay overnight. Signed “your sincerely loving Behrs”.

I-6. Sofia Andreevna Tolstaya, Tula, 1866.

Photo by Felitsian Ivanovich Khodasevich

I-7. Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy as a warrant officer in the Imperial Russian army.

Daguerreotype, 1854

I-8. Sofia Andreevna Tolstaya with her two eldest children: Sergej L’vovich [Serëzha] (b. 1863)

(right) and Tat’jana L’vovna [Tanja] (b. 1865) (left).

Photo: Tula, 1866

I-9. Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy’s letter to his wife written on the day of his final departure from Yasnaya Polyana, 28 October 1910. (The two words at the top read “To Sofia Andreevna”.)

It appears as Letter Nº 234 in the present volume.

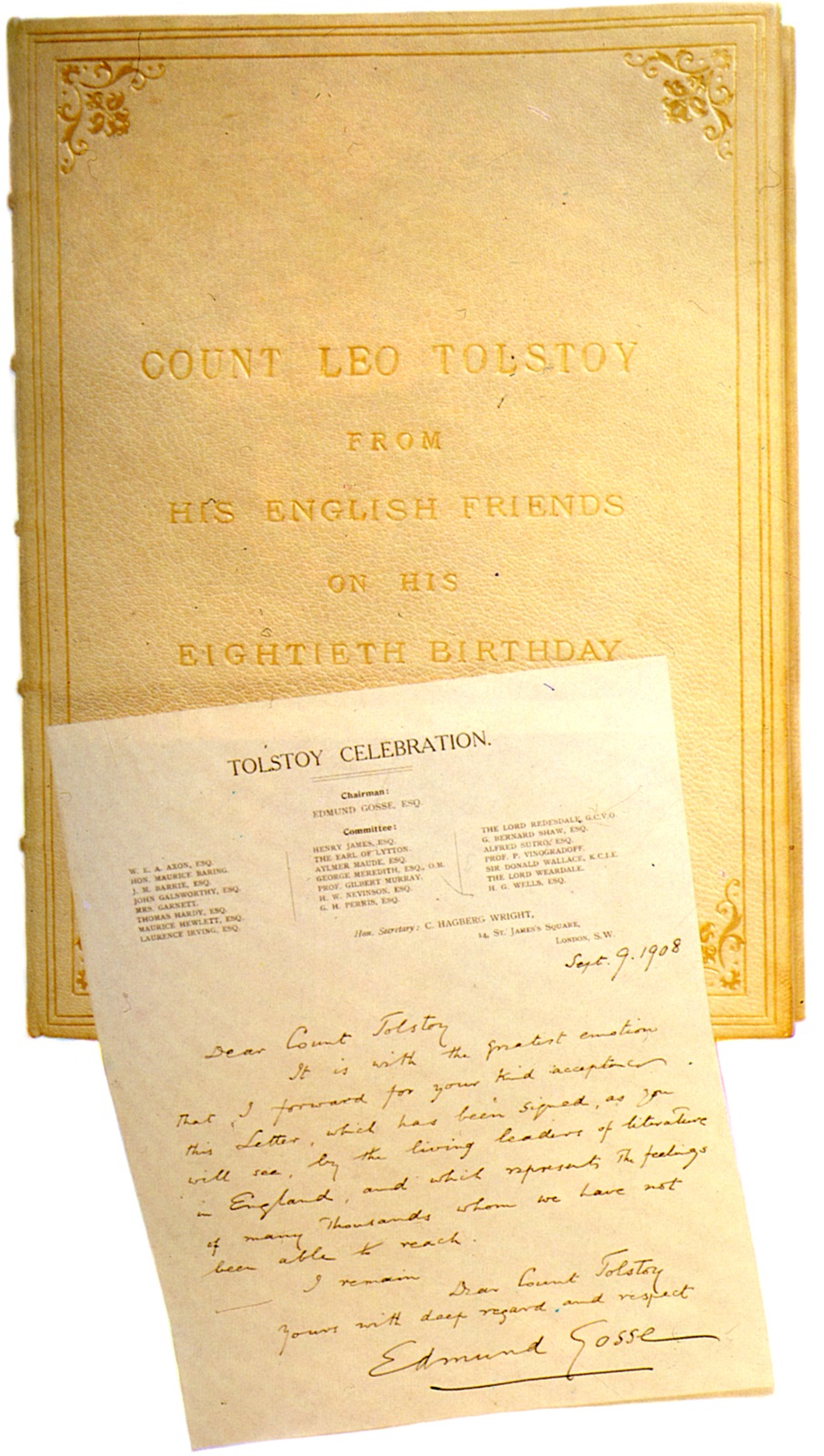

I-10. A booklet of congratulatory messages to Count Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy on his 80th birthday, 28 August 1908 O. S. (9 September N. S.), with an accompanying letter signed by English author Edmund Gosse.

I-11. Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy, 1878 or 1879.

Photo by Mikhail Mikhajlovich Panov

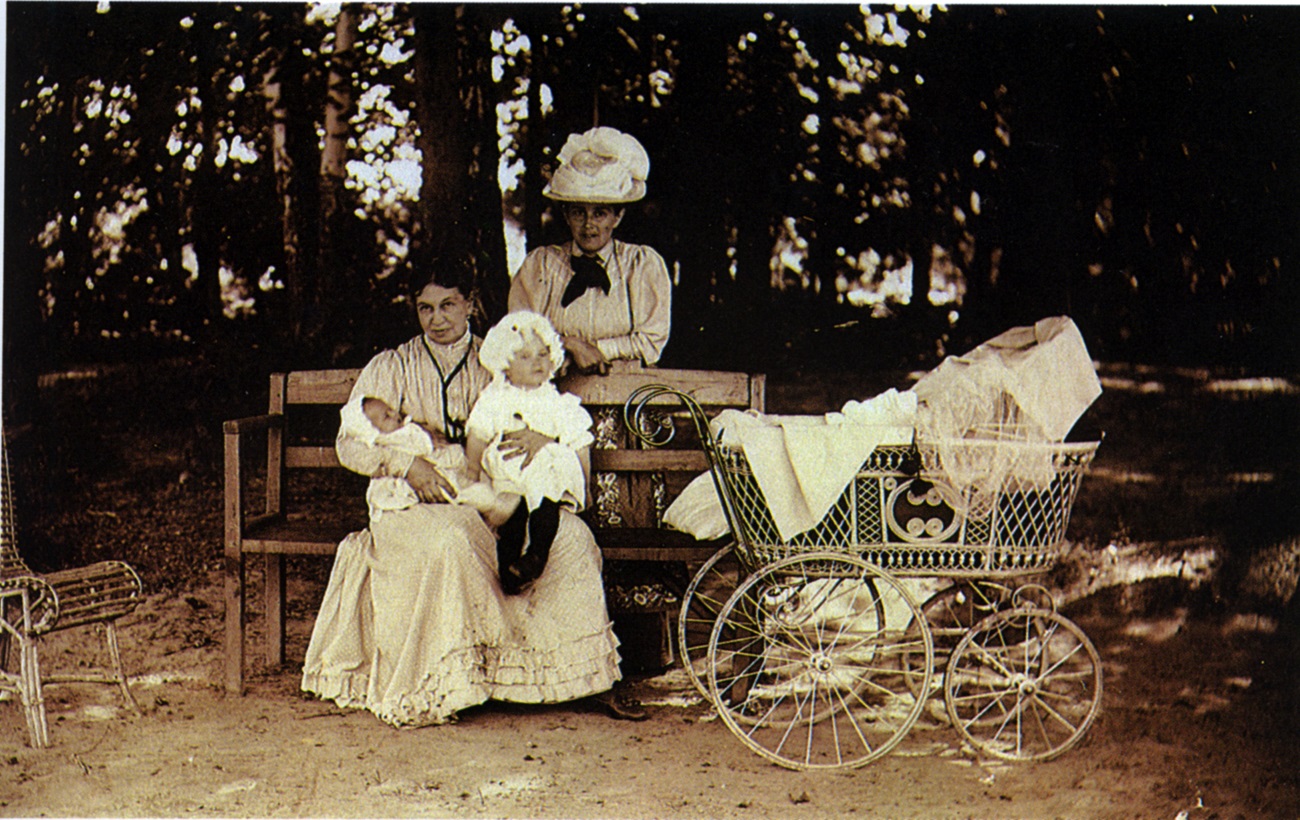

I-12. Sofia Andreevna Tolstaya with two of her grandchildren (Sonja and Lev), along with her daughter-in-law (Andrej L’vovich’s wife) Ol’ga Konstantinovna Tolstaja (née Diterikhs).

Photo by Sofia Andreevna Tolstaya,October 1900

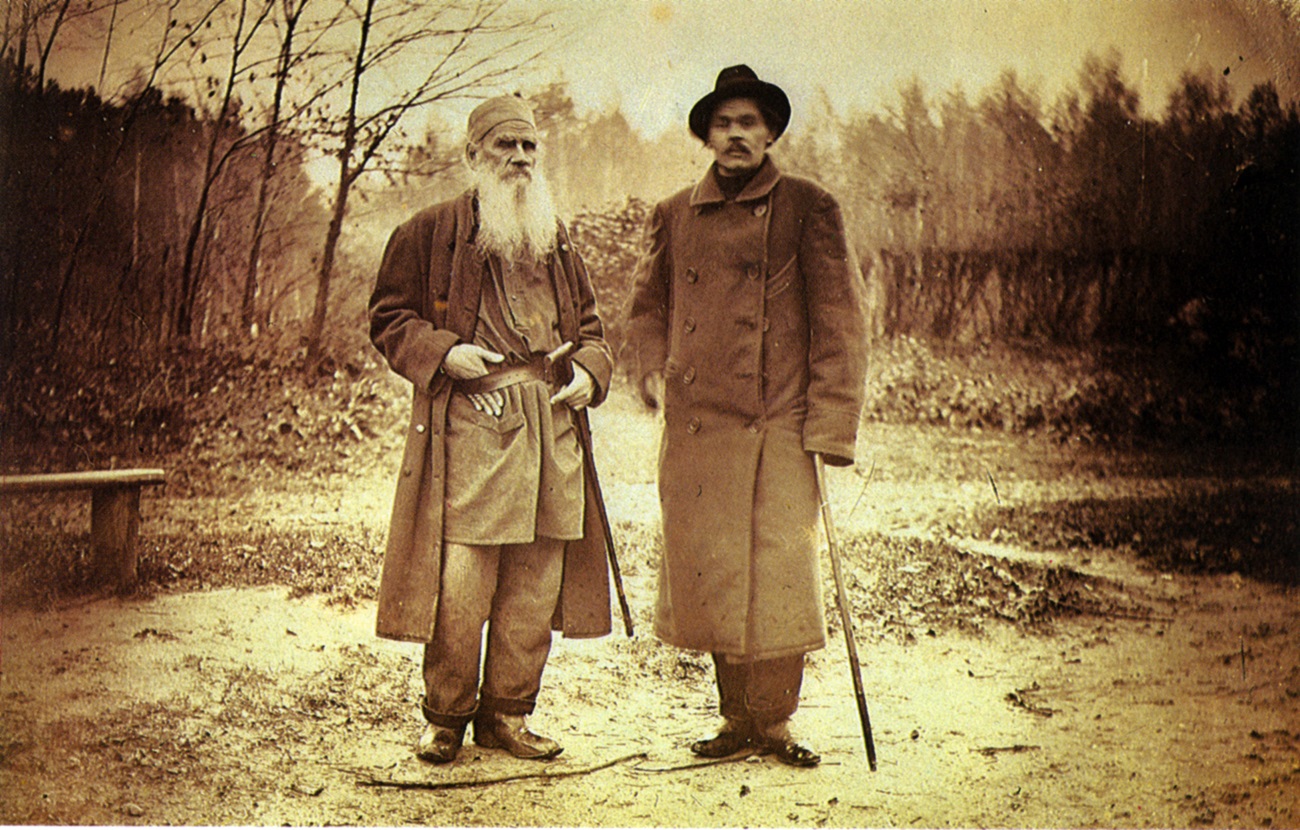

I-13. Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy with writer Maksim Gorky, Yasnaya Polyana, 1900.

Photo by Sofia Andreevna Tolstaya

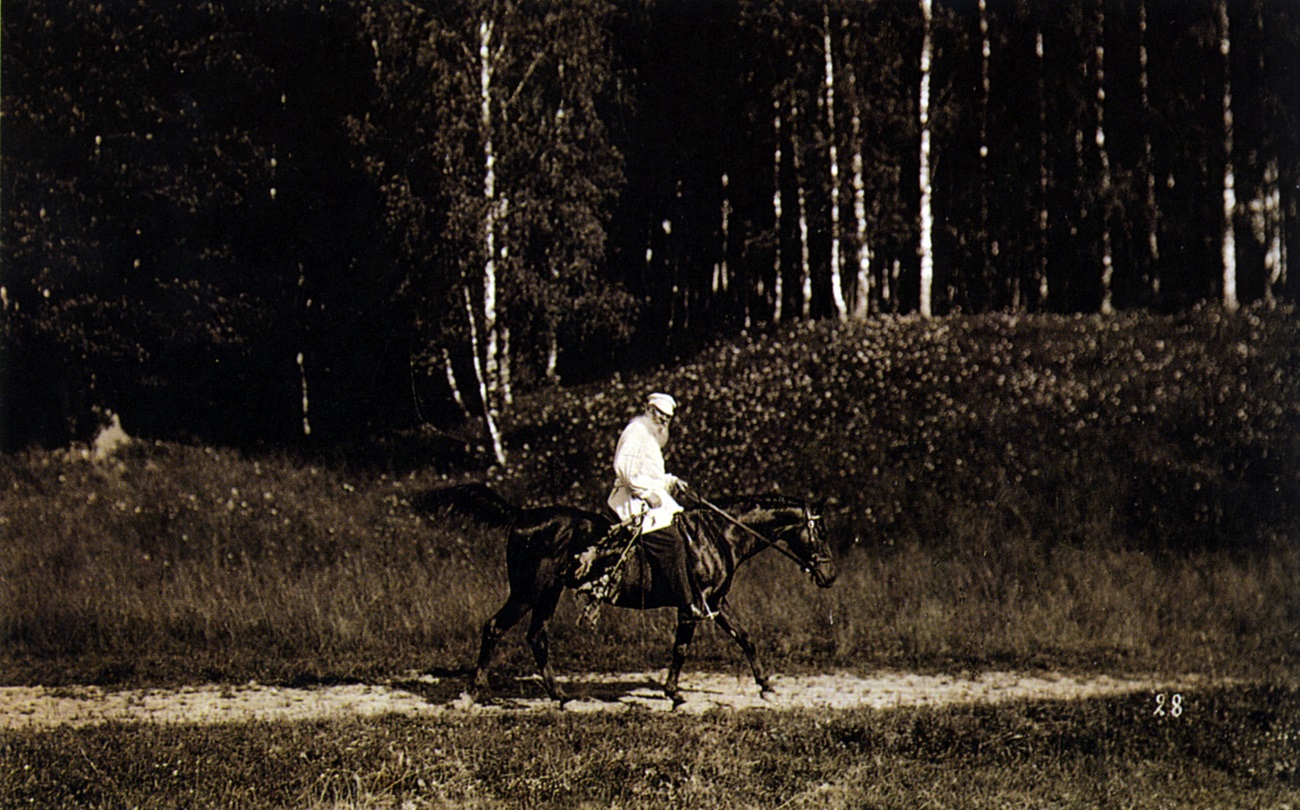

I-14. Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy on horseback near Yasnaya Polyana, 1908.

Photo by Karl Karlovich Bulla

I-15. Ivan L’vovich Tolstoj (Vanja, Vanechka), the Tolstoys’ youngest son (1888–1895).

Photo by Sherer, Nabgol’ts & Co, 1893 or 1894

I-16. Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy telling a story to his grandchildren Iljusha (centre) and Sonja (right), children of Andrej L’vovich Tolstoj, September 1909.