IN 1601, Philemon Holland, introducing his English version of the elder Pliny’s Natural History, writes of it as his bid to become part of what already, with time still left on the clock, feels like the institution later known as the Elizabethan age. Translation is a ‘third ranke’—after those of noble deeds and original literature—in which one might achieve enduring fame through being part of that moment:

As for my selfe, since it is neither my hap nor hope to attaine to such perfection, as to bring foorth somewhat of mine owne which may quit the pains of a reader, and much lesse to performe any action that might minister matter to a writer, and yet so farre bound unto my native countrey and the blessed state wherein I have lived, as to render an account of my yeers passed & studies employed, during this long time of peace and tranquilitie, wherein (under the most gratious and happie government of a peerelesse Princesse, assisted with so prudent, politique, and learned Counsell) all good literature hath had free progresse and flourished, in no age so much: me thought I owed this dutie, to leave for my part also (after many others) some small memoriall, that might give testimonie another day what fruits generally this peaceable age of ours hath produced.1

Merging his ambition into that of his nation, Holland becomes increasingly fervent about the importance of translation, especially from the ancient classics; critics of his craft are rebuked with the assertion that such translation is itself a warrior’s calling, providing the country with a kind of postcolonial payback:

Certes such Momi as these … thinke not so honourably of their native countrey and mother tongue as they ought: who if they were so well affected that way as they should be, would wish rather and endeavour by all means to triumph now over the Romans in subduing their literature under the dent of the English pen, in requitall of the conquest sometime over this Island, atchieved by the edge of their sword.2

The trope is a passing one, but the representation of translation as a patriotic enterprise, already evident in Holland’s version of Livy the previous year (where Holland is the sponsor of a deserving immigrant who will bring ‘this nation of ours … great fruit and benefit’), 3 is sustained throughout Holland’s literary career, which proves to be a long one—centred firmly on the translation of classical prose—and which indeed earns him some measure of the fame he sought. Thomas Fuller, including him in The Worthies of England, entitled him ‘the Translator Generall in his Age’, whose ‘Books alone of his Turning into English, will make a Country Gentleman a competent library for Historians’;4 the collected Holland weighs down a bookshelf in Pope’s Dunciad. He is the eighth most cited writer in the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary. His prefaces set the tone of F. O. Matthiessen’s Translation: An Elizabethan Art, and through it of much subsequent discussion of England’s early modern translators: ‘The translator’s work was an act of patriotism. He, too, as well as the voyager and merchant, could do some good for his country: he believed that foreign books were just as important for England’s destiny as the discoveries of her seamen, and he brought them into his native speech with all the enthusiasm of a conquest.’5

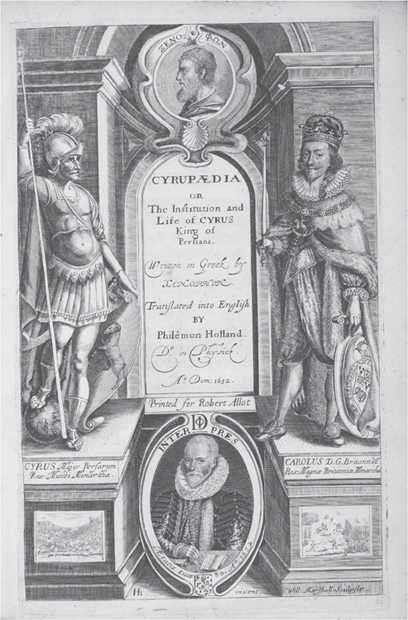

Holland was prompted in his ambition—he acknowledges it more than once—by the example of Sir Thomas North’s monumental translation of Plutarch’s Lives (1579). Holland’s Livy and Pliny, as well as later translations of Plutarch’s philosophical works (1603, in effect completing North’s project), Suetonius (1606), Ammianus Marcellinus (1609), William Camden’s Britannia (1610), and, rounding out his career in a volume adorned with valedictory encomia, Xenophon’s Cyropaedia (1632) (Fig. 7.1), are in the same general mould: handsome folio volumes running sometimes over a thousand pages, prestige productions fetching a premium price, though not entirely beyond the means of sufficiently interested general readers (a bound copy of North’s first edition retailed for 14s; Holland’s Pliny, unbound, went for 13s).6 Even for someone as industrious as Holland, income from this source was not enough to live on. There is record of his receiving £4 for his Ammianus and £5 for his Camden (on the low side of what a successful London playwright might receive for a single play);7 during most of his time as a translator he worked at the free school in Coventry and as a practising physician, and despite a small pension from Coventry, he appears to have been in distressed circumstances in his last years. Unsurprisingly, no one else made such a career out of this kind of translating. But the books themselves appear to have sold; they were frequently reprinted, and booksellers kept offering new ones: Josephus and Seneca’s philosophical works translated by Thomas Lodge (1602, 1614; the Seneca revised in 1620), Tacitus by Sir Henry Savile (Histories I–IV and Agricola, 1591) and Richard Greenwey (Annals and Germany, 1598), Thucydides by Thomas Hobbes (1629; his first publication), and Augustine’s City of God by John Healey (1610). There was a recognized market for classics of Latin and Greek prose dressed out (Holland is fond of the clothing metaphor) as classics of English prose.

FIGURE 7.1 Xenophon, Cyropaedia, trans. Philemon Holland (1632), title page

Most translations of classical prose were not of course given this kind of high-end production. The most widely used circulated in more modest editions; a bound copy of the first issue Nicholas Grimald’s version of Cicero’s On Duties (1556), ‘one of the most published secular works of the sixteenth century in England’, could be had for 8d.8 But the expensiveness of the large format translations does not appear to have inhibited their influence. The most famous, indeed, spectacular case of such influence, is the impact of North’s Plutarch on Shakespeare, an impact which is extensive and detailed and in more than a few places seems to have involved having North open before him as he wrote.9 No cheap selection from North’s Lives was available (none of the big editions had their material remarketed that way) and purchasing a copy would have required careful planning on a playwright’s income (which might run £20–30 a year); one way or another, Shakespeare managed. There is trace evidence as well that he worked with Holland’s Livy and Plutarch—the latter for the Egyptian lore in On Isis and Osiris—and even his Camden.10 Holland’s practice is also sufficiently exemplary of the handling of classical prose by translators throughout the period to justify treating him as a kind of standard.11

That handling is closer to a modern standard of fidelity than is generally operative in translations of vernacular prose or of any kind of verse. There are exceptions to this generalization, though they tend to come early. In one freewheeling example, Angel Day publishes the first English version of Longus’s pastoral romance Daphnis and Chloe (1587) with an interpolated tribute to Queen Elizabeth entitled ‘A Shepheards Holidaie’ and a title page identifying Day as its author, with in fact no acknowledgement that the rest of the volume is a translation. A shade more discreetly, Alexander Barclay’s translation of Sallust’s Jugurtha (1522, reprinted with revisions by Thomas Paynell in 1557) interleaves the story with emphatic signposting. ‘In this warke I purpose to wryte of the batayle/which the Romayns had and executed agaynst the tyranne Jugurth wrongfully usurpynge the name of a kynge/over the lande of Numydy’: ‘tyranne’ and ‘wrongfully usurpynge’ are wholesale additions, as the Latin which Barclay prints in the margin clearly shows.12 The translator elsewhere stated his principles without apology—‘some tyme addynge, somtyme detractinge and takinge away suche thinges [a]s semeth me necessary and superflue’13—and others throughout the period casually followed them; but at least in connection with classical prose (and outside the special cases where prose is translated as verse) there is less in this line as we go on. Thomas Heywood’s Sallust (1608) is conspicuously more restrained than Barclay’s: ‘In this Booke, my purpose is, to write the Warre which the Romane people undertooke against Jugurth King of Numidia.’14

We do regularly find intruded glosses, incorporating information that might go into a marginal note or a bracketed insertion within the text—and sometimes does, but also sometimes is wholly assimilated to the translation itself. A wish to anticipate and meet the readers’ needs in an unfussy way also animates a pervasive concern often made explicit in the translators’ own prefaces. The patriotic mission that Holland claims for translation has a linguistic component, a chauvinism about the English language itself: ‘I honour them in my heart, who having of late daies troden the way before me in Plutarch, Tacitus, and others, have made good proofe, that as the tongue in an English mans head is framed so flexible and obsequent, that it can pronounce naturally any other language; so a pen in his hand is able sufficiently to expresse Greeke, Latine, and Hebrew.’15 The adjectives ‘flexible and obsequent’ suggest deference to the way things are done elsewhere, but the message here is really the unique capacity of English; Holland’s strong inclination is against ‘foreignizing’. The most contentious issue in contemporary polemics about translation is the use of ‘inkhorn terms’; Holland is sensitive to the need to import certain kinds of technical language, but sparing in doing so, and sufficiently self-conscious about it to include glossaries ‘of such woords of Art … with the explanation thereto annexed, and the same delivered as plainly as I could possibly devise for the capacitie of the meanest’.16 Holland went so far as to imagine a readership including ‘the rude paisant of the countrey’ and ‘the painefull artizan in town and citie’, and in this spirit ‘I framed my pen, not to any affected phrase, but to a meane and popular stile. Wherein, if I have called againe into use some old words, let it be attributed to the love of my countrey language: if the sentence be not so concise, couched and knit togither, as the originall, loth I was to be obscure and darke: have I not englished everie word aptly?’17 The emphasis falls on ‘englished’; the final criterion is attractive management of the target language.

Other translators are not necessarily as interested in reaching peasants and artisans, but similar principles can be recognized in their work. The practice falls under the general model that Massimiliano Morini derives from humanist theory and argues is dominant for this period in England: ‘they do not alter the inventio and dispositio of their sources, but feel free to adapt the elocutio, the style, to their and their audience’s taste’.18 As a contemporary puts it: ‘retayning the strength and sinew of the Sentence [meaning], I have rendred it as best fitted the property of speech in our owne language’.19 The usual result is casually expansive, though generally not without perceptible warrants in the original. Individual words are rendered with doublets or triplets, epigrammatic constructions (‘concise, couched and knit togither’) are rendered paraphrastically, connectives are added to ease the sequence of thought or action, and lighting effects occasionally heighten the moment: ‘For fear of this reproch and infamie, see how sinfull lust gat the victory, and conquered constant chastity’; needless to say, ‘see’ is not in the Latin.20 Especially long sentences are broken up or recast and—the feature most likely to strike modern readers—a line of what Matthiessen likes to call ‘racy’ diction runs through almost everything: e.g. ‘This unhappie occurrent made us bestirre our stumpes’ for ‘hoc malo conciti’.21 To modern ears this is a drop in register, not what you expect in a classic, but neither translators nor their readers seemed to have a problem with it. Much is probably owed to the admirable precedent of North’s Plutarch, where the diction offsets but also empassions a stateliness that comes from extraordinarily flexible and obsequent mimicking of the syntax, cadence, and word order of Jacques Amyot’s French translation, the text from which North worked; the result manages to sound not French at all:

it was not the great multitude of shippes, nor the pompe & sumptuous setting out of the same, nor the prowde barbarous showts & songes of victorie that could stande them to purpose, against noble harts & valiant minded souldiers, that durst grapple with them, & come to hands strokes with their enemies: & … they should make no reckoning of all that bravery & bragges, but should sticke to it like men, & laye it on the jacks of them.22

The timbre of the prose supplies its own gloss for the obsolete slang at the end; no note is really needed. North found a highly credible voice in which ancient civilization might speak with authority and force in a contemporary environment, and the main line of classical prose translations more or less follows his lead.

It is a voice above all for politics and warfare, but it also has a gift for the fantastical. The most famous passage in North is so because Shakespeare virtually transcribed it in describing Cleopatra’s fabulous self-deification on her way to meet Antony: ‘she disdained to set forward otherwise, but to take her barge in the river of Cydnus, the poope whereof was of gold, the sailes of purple, and the owers of silver, which kept stroke in rowing after the sounde of the musicke of flutes, howboyes, citherns, violls, and such other instruments …’23 Shakespeare adds embellishments, but North is already with the programme: Plutarch says nothing about rowers keeping time to the music. The most spacious opportunity for such appreciation turns out to be Holland’s Pliny, where the familiar and exotic phenomena of the natural world are the occasion of repeated wonderment: ‘As for Cats, marke I pray you how silent they be, how soft they tread when they steale upon the silie birds: how secret lie they in espiall for the poore little Mice to leape upon them.’24 There is no specific prompting in the Latin for silie or poore or, most significantly, marke I pray you; the English cradles the sense of the original in a kind of heightened attentiveness. Pliny’s description of the song of the nightingale calls forth multiple cadenzas from the translator:

one while, full of her largs, longs, briefes, semibriefes, and minims; another while in her crotchets, quavers, semiquavers, and double semiquavers: for at one time you shall heare her voice full and lowd, another time as low; and anon shrill and on high: thicke and short when she list; drawne out at leisure againe when she is disposed: and then (if shee be so pleased) she riseth & mounteth up aloft, as it were with a wind-organ. Thus she altereth from one to another, and singeth all parts, the Treble, the Meane, and the Base. To conclude, there is not a pipe or instrument againe in the world (devised with all the Art and cunning of man so exquisitely as possibly might be) that can affourd more musicke than this pretie bird doth out of that little throat of hers.25

This, about half of a passage conjured from some fifty words of Latin. Pliny’s chapter is the source for much of the lore about nightingales in the Renaissance, including those contests in which a particularly competitive bird literally sings itself to death. That legend supplies the conceit for Famiano Strada’s neo-Latin poem about a duel between a nightingale and a lutenist (1617), which Richard Crashaw translates into English as ‘Musicks Duell’ (1646) with rapturous amplifications very much in Holland’s spirit and quite possibly suggested by his example.26 The grounds on which Holland recommends Pliny to his reader are, sensibly, more literary than scientific—‘surely it is antiquitie that hath given grace, vigor, & strength to writings; even as age commendeth the most generous and best wines’27—and to read through the translation—‘almost … a Renaissance phantasmagoria when read at a stretch’—is to encounter time and again information and images that are strewn throughout seventeenth-century English literature and the other arts.28

The medium has a homogenizing effect; stylistic differences in the source texts, though recognized (on Ammianus, Holland notes ‘the harsh stile of the Author, a Souldior, and who being a Grecian borne, delivered these Hystoricall reports in Latine’29), generally are not represented clearly in English. The excesses of Apuleius—‘ever the literary fop, conscious of his trappings and assured of a handsome effect’30—might have been a natural for uninhibited euphuistic treatment in the new language and William Adlington occasionally gets into the spirit in his Golden Asse (1566); but in general, his translation desaturates the original’s colour. Latin thieves carouse in hyperbolic high style—‘estur ac potatur incondite, pulmentis aceruatim, panibus aggeratim, poculis agminatim ingestis’ (something like: ‘there was riotous eating and drinking, mountains of meat, heaps of bread, battalions of cupfuls’)—while in English ‘thei dranke & eate excedingly’; Apuleius’s ‘ab ipsa Venere septem sauia et unum blandientis adpulsu linguae longe mellitum’ (‘seven kisses from Venus herself, and one honeyed by the lingering touch of her ingratiating tongue’) scale down to ‘seven sweete cosses of Venus’.31 Like North, Adlington is being closely guided by an intervening French translation, 32 though he is also working from the Latin and aware of what he is not bringing over into English. Apuleius ‘had written his woorke in so darke and highe a stile, in so strange and absurde woordes, and in such newe invented phrases, as he seemed rather to set it foorth, to show his magnifency of prose, then to participate his dooinges to other’; accordingly,

I have not so exactly passed thorough the Author, as to pointe every sentence accordinge as it is in Latine, or so absolutely translated every woorde, as it lieth in the prose … considering the same in our vulgar tongue would have appeared very obscure and darke, & thereby consequently, lothsome to the Reader, but nothing erringe as I trust from the given and naturall meaninge of the author, have used more common and familiar woordes … for the plainer settinge foorth of the same.33

He is not talking only about diction.

The wish to make the work sit comfortably in English more often leads to elaboration and expansion. Beginning in the late sixteenth century, this tendency encounters growing interest in classical writers valued for commandingly trenchant and difficult styles, riskier business for translators already hypersensitive to the prospect of aggravating their public. Of Seneca, Lodge writes, ‘the Author being seriously succinct, and full of Laconisme; no wonder if in somthings my omissions may seeme such, as some whose judgement is mounted above the Epicycle of Mercurie, will find matter enough to carpe at’.34 Important claims have been made for the role of such ‘anti-Ciceronian’ prose in English intellectual life in the seventeenth century, 35 though translators are uneven in attempting to represent this aspect of the classical works in question. Some scarcely bother; in what might be some kind of joke, Heywood sounds like Polonius when expanding Sallust’s paucis sixfold: ‘wherin, I vow all possible Brevity’.36 Lodge intermittently tries to keep Seneca’s compact phrasing, sometimes with unintelligible results; ‘magis quis ueneris quam quo interest’ (‘it is more important who you are when you travel than where’) is mangled into ‘It importeth more to know what thou are comming, then when thou arrivest.’ Successful attempts typically merge into something more relaxed:

non est delicata res uiuere. longam uiam ingressus es; et labaris oportet et arietes et cadas et lasseris et exclames ‘o mors!’, id est mentiaris.

It is no delicate thing to live. Thou art entered into a long way, wherein perforce thou must slip, thou must justle, thou must fall, thou must be wearied, and thou must exclaime, O death! that is, thou liest.

That first phrase hits the target exactly. The rest, without adding anything to the sense, massages the nervously emphatic rhythm of the Latin into a more flowingly ‘Ciceronian’ cadence.37

In a preface to Savile’s Tacitus, ‘A.B.’ calls the original author ‘harde’ and promises the reader that the translator ‘gives thee the same foode, but with a pleasant and easie taste’.38 But the translation mostly has the confidence of its own ungraciousness, regularly reproducing the choppiness of the Latin and expanding more for clarity than for elegance. ‘To take away by maine force, to kill and to spoile, falsely they terme Empire and government: when all is waste as a wildernesse, that they call peace’—Savile more than doubles the word count (‘auferre trucidare rapere falsis nominibus imperium, atque ubi solitudinem faciunt, pacem appellant’), but does not dull either the analytic sharpness or the venom.39 So also the assessment of how public perception fatally manoeuvred Servius Sulpicius Galba into a job he could not handle:

his honorable birth, and the dangerous times covered the matter, entitling that wisedome, which in truth was but slouth: in his flourishing age greatly renowned for service in Germanie: Africke he ruled as Proconsull with great moderation: and growing in yeares, the nearer Spaine uprightly & well: seeming more than a private man, whilest he was private, and by all mens opinions capable of the Empire, had he never bene Emperour.40

The translation was much respected; Jonson praised Savile for catching both Tacitus’s meaning and style (Epigrams 95). Greenwey, though less accomplished, imitated Savile’s manner well enough to make for a reasonably uniform collected works.

The non-standard Greek of Thucydides is in some ways even more of a challenge and Hobbes’s response goes against the grain celebrated by Matthiessen. An earlier effort, by Thomas Nicolls (1550), openly relied on Lorenzo Valla’s Latin version and Claude de Seyssel’s French one; Hobbes, proudly able to work directly from the Greek, produced a sturdily straightforward version that is consistently shorter:

But the woorste that was in this, was that men loste their harte, & hope incontynently, as they feeled themself attaincted. In suche sort, that many, for despaire, holdinge themselves for dead, habandoned & forsoke themself, & made no provisyon nor resistence againste the sickenes. And an other great evill was, that the malady was so contagious, that those, that went for to visitt the sicke, were taken and infected, lyke as the shepe be, one after an other.

But the greatest misery of all was, the dejection of mind, in such as found themselves beginning to be sicke (for they grew presently desperate, and gave themselves over without making any resistance) as also their dying thus like sheepe, infected by mutuall visitation, for the greatest mortality proceeded that way.41

Hobbes’s brevity follows from something close to the uerbum pro uerbo translating that other translators regularly profess to scorn. Where Nicolls essentially begins again halfway through, Hobbes mimics the continuous sentence structure of the Greek and he avoids the doublets (‘harte, & hope’, ‘habandoned & forsoke’, and ‘no provisyon nor resistence’) and new signposting (‘And an other great evill was’) that come naturally to his predecessor; he also declines the heightened poignancy that comes with repositioning and prolonging the reference to sheep, but respects Thucydides’s characteristic restraint in the use of metaphor.

The overall result has been well characterized by Robin Sowerby: ‘despite the occasional high Latinism or homely colloquialism, this is plain, customary (though not neat), direct, blunt, analytical expository prose without frills, ambiguities, or tropes that draw attention to themselves’.42 Hobbes’s translation has been called the ‘most distinguished of historical translations in the period’, but also ‘for all his Jacobean credentials … dull’.43 A certain avoidance of rhetorical and literary effectiveness, though not universal, seems to have been part of the point, consonant with the distrust that both Thucydides and Hobbes felt for figurative language and oratorical skill; in his verse autobiography (1672), Hobbes will remember his motivation for the translation in these terms: ‘Hunc ego scriptorem uerti, qui diceret Anglis,/Consultaturi rhetoras ut fugerent’ (‘I translated this writer to tell the English to flee the rhetoricians they were about to consult’).44 It seems appropriate that Hobbes stumbles at Pericles’s summary of the Athenian aesthetic ideal: ‘we also give ourselves to bravery, and yet with thrift’ for ϕιλοκαλοῦµ∈ν τ∈ γὰρ µ∈τ’ ∈ὐτ∈λ∈ίας.45 Richard Crawley’s Victorian translation does not break stride: ‘We cultivate refinement without extravagance.’46 Hobbes’s Athenians speak with most conviction when standing for something less genteel: ‘at first wee were forced to advance our Dominion to what it is, out of the nature of the thing it selfe; as chiefly for feare, next for honour, and lastly for profit’.47 The trinity of fear, honour, and profit is already there in Nicolls, though Nicolls passed over the phrase that Hobbes renders ‘out of the nature of the thing it selfe’: Hobbes’s speaker is formulating a scientific law of how it is with human beings and ‘Dominion’ (ἡγ∈µονή; the Latin would be imperium). A reordered version of this trinity reappears in Leviathan: ‘in the nature of man, we find three principall causes of quarrell. First, Competition; Secondly, Diffidence; Thirdly, Glory.’48 Translating Thucydides, Hobbes looks forward to his later career, with its quest for a cold-blooded intellectual austerity both stylistic and substantive.

Most of the examples here have been from history. Most of the texts which Holland chooses to translate are in this category, which dominates among other translators as well; it is in history that they come closest to offering Anglophone readers comprehensive access to what classical writers had to offer. Coverage of the classical canon in general is famously spotty.49 It was dependent on accidents of individual initiative (Holland the distinguished example), the importunity of friends (often cited by the translators themselves), aristocratic patronage (more often sought than received), and especially the judgement of booksellers, who commissioned most of the translations, as to what would sell. England had no publisher with the strong humanist allegiances of Aldus Manutius in Venice, the Estiennes in Paris, or Christoph Plantin in Antwerp; the only significant government support for translation concerned the Bible. The great contrast was with France, where royal patronage helped give shape to the whole enterprise.50 Several French translators—Amyot, Seyssel, Nicolas Oresme (from the fourteenth century, his works printed in the late fifteenth), and Louis Le Roy—sustained careers similar to Holland’s, though unlike his, subsidized by positions at court and ecclesiastical appointments. Some of their achievements, especially with Greek writers, paved the way for English successors; Amyot’s French Plutarch, specifically commissioned by Francis I, was used by both of the two English translators it took to cover the same ground and was indispensable for one of them (North includes a translation of Amyot’s preface). In other cases, the availability of reliable French translations—such as Le Roy’s versions of Plato’s Republic, Timaeus, and Symposium—may actually have kept English versions of key canonical texts from seeming worth the trouble.

Philosophy is the area with the most conspicuous gaps for English translation.51 Plato especially: the invisible hand does not find its way to him until after this period, when it has the guidance of Thomas Stanley’s History of Philosophy (1655–62), itself containing extensive translations from primary texts. Aside from excerpts in anthologies and elsewhere, there is only Axiochus, a spurious dialogue of particularly Christian resonance englished by ‘Edw. Spenser’—probably Edmund—in 1592 and by an anonymous translator for a collection in 1607. For Aristotle, there are a version of the Nichomachean Ethics made from a thirteenth-century Latin abridgement (1547) and John Dee’s translation of the Politics from Le Roy’s French (1598, including Le Roy’s own prefatory essay). Epictetus’s Enchiridion is translated twice (1567, 1610), his Discourses not at all; Meric Casaubon’s Marcus Aurelius appears in 1634. Holland’s Plutarch is preceded by several versions of individual works: ‘Plutarch’s talent for the brief moral essay, intricately wrought, makes translations from him a perfect gift’52—beginning with Sir Thomas Wyatt presenting The Quyete of Minde to Catherine of Aragon (1528). Outside of Lodge’s folio a few Senecan and pseudo-Senecan works are also translated by others. There are scattered translations of individual works by Cicero, but the closest thing to a general collection is Thomas Newton’s gathering of four of them (On Old Age, On Friendship, The Dream of Scipio, and Paradoxes) in 1577. The most popular single Ciceronian work in English is Grimald’s On Duties, not so much a work of philosophy as a primer on Roman civic life. It may be that in philosophy the paganism of antiquity was more of a problem for English readers than elsewhere; translators repeatedly address the issue in ways meant to be reassuring (‘What a Stoicke hath written, Reade thou like a Christian’).53 The most translated philosopher from antiquity, in continuance of a tradition going back to Alfred the Great, is the possibly or almost Christian, Boethius: five complete versions of his Consolation of Philosophy during this period, two printed (1556, 1609), three in manuscript (one by Queen Elizabeth), as well as some stand-alone translations from the metra. The most passionate public debate about a particular translated text in any genre—with much seen as riding on small verbal differences—involved competing Catholic and Protestant translations of Augustine’s Confessions (1620, 1631).54

Coverage is fairly thorough for imaginative literature from antiquity, though in prose this is a small corpus. The fables of Aesop are Englished repeatedly, in different forms; in accord with the reported practice of Socrates (Plato, Phaedo 60D), several of these are in verse.55 Adlington’s Apuleius becomes the first in a series that brings into print English versions of most of the late classical prose romances that survive intact: Heliodorus’s Theagenes and Chariclea (partial translations in 1567 and 1591, complete ones in 1569 and 1631), Longus’s Daphnis and Chloe (1587), the anonymous Apollonius of Tyre (by way of the thirteenth-century Gesta Romanorum, 1594), and even Achilles Tatius’s deliberately bizarre Leucippe and Cleitophon (1597 and 1638). The influence of these works in Elizabethan literature has been much discussed.56 Apuleius is the only one of these authors to offer a serious stylistic challenge to translators. Their erotic content sometimes needed muting. Adlington alerts readers of his first edition that he has ‘left out certain lines propter honestatem’ when his assified narrator copulates with an aroused noblewoman, though it remains clear just what is going on.57 Day completely excises from Daphnis and Chloe the hero’s sexual initiation by the helpful young wife of an elderly neighbour; the episode is restored in George Thornley’s translation in 1657.

The appetite for the classical historians, however, especially of Rome and its Empire, is deeper and broader. The enterprise of bringing them into English picks up pace as the period goes on; by 1640—after Arthur Grimeston’s complete Polybius (1633) succeeds a false start by Christopher Watson (1568)—the one egregious gap remaining is Herodotus, represented only by Barnabe Rich’s translation of the first two books.58 The appetite is not solely literary; it includes practical handbooks of what Captain Fluellen (Henry V 3.2.81–2) calls ‘the disciplines of the Pristine Warres of the Romans’: Frontinus (1539), Vegetius (1572), and Aelian (1616). Translators of fragmentary sources can be enterprising at filling factual lacunae. Holland accompanies his Livy with summaries (misattributed to Florus) of the missing books, as well as a continuous chronology; Savile provides a bridge of his own composition to link the end of Tacitus’s Annals to the start of his Histories (translated into Latin, it makes its way into editions of Tacitus). The result is, among other things, to shift classical history from an array of stories about particular people into a larger story of how things went over a long period of time for a particular state. With this shift can be sensed a change in the kind of urgency that the classical sources are felt to manifest. The earlier inclination is to offer them as incentives to general virtue of an upscale sort. Barclay recommends Sallust ‘specially to gentylmen/which coveyt to attayne to clere fame and honour: by glorious dedes of chyvalry’; North includes Amyot’s praise of history as ‘a very lively & sharpe spurre for men of noble corage and gentlemanlike nature, to cause them to adventure upon all maner of noble and great things’, while adding on his own that the examples which count the most are of those who ‘ventured their persons, cast away their lives, not onely for the honor and safety, but also for the pleasure of their Princes’.59 Holland shows something of the same spirit when he describes his Livy as ‘an english Historie of that C. W. which of all others … affourdeth most plenteous examples of devout zeale in their kind, of wisedome, pollicie, justice, valour, and all vertues whatsoever’;60 but even in doing so he signals that the C. W.—the Commonwealth—is the real protagonist of the history that follows. It is moreover the history of when that commonwealth was a republic; Holland’s praise of Elizabeth and her regime may have been entirely sincere, but in the anxious time of her last years the very choice of Livy to translate was a potentially provocative act—especially when the new accessibility of Tacitus made the contrast between Rome’s republican and monarchical times particularly disadvantage the latter.61 Savile’s introductory addition to Tacitus includes what is for an Elizabethan a wholly extraordinary judgement on Julius Vindex, who lost his life for conspiring against Nero:

a man in the course of this action more vertuous than fortunate; who … first entred the lists, chalenging a Prince upholden with thirty legions, rooted in the Empire by fower descents of ancestours, and fourteene yeares continuance of raigne, not upon private dispaire to set in combustion the state, not to revenge disgrace or dishonour, not to establish his owne soveraignety … but to redeeme his cuntrey from tyranny and bondage, which onely respect he regarded so much, that in respect he regarded nothing his owne life or security.62

Lightly disguised as an imitation of Tacitus, the passage is a signal to the reader as to how to read the genuinely Tacitean text to follow: monarchical rule such as Nero’s, however legitimate, can make rebellion an act of virtue. That is not a lesson Barclay or North or probably even Holland would have countenanced, but it was a text to ponder for those troubled by a rising (and accurate) sense that England was being carried into political waters for which nothing in its own history prepared it.

Hobbes occupied a different place on the political spectrum, but his sense that classical history could be an important source of guidance in dangerous times was even more overt. The partisan topicality of his Thucydides is evident in a preface that argues, with some justification in the text, that the Greek historian—‘the most Politique Historiographer that ever writ’—was ‘a closet royalist’, and in the regular translation of stasis, the term for political faction, as ‘sedition’.63 The full scope of that topicality had yet to reveal itself: with cool prescience, Hobbes ventured beyond the focus on Rome to find the great classical history of civil war—far more searching than Caesar’s mainly military history of the Roman equivalent—and published his translation of it at the beginning of the reign of Charles I. The rhetores against whom he said he wished to warn the English by doing so would of course have been mainly parliamentarian.

Bennett, H. S. English Books and Readers, 1558 to 1603 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1965).

—— English Books and Readers, 1603 to 1640 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970).

Braden, Gordon, Robert Cummings, and Stuart Gillespie, eds. The Oxford History of Literary Translation in English, Volume 2: 1550–1660 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

Conley, C. H. The First English Translators of the Classics (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1927).

Croll, Morris W. Style, Rhetoric, and Rhythm: Essays, ed. J. Max Patrick (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1966).

Ebel, Julia G. ‘A Numerical Study of Elizabethan Translations’, The Library, 5th ser., 22 (1967): 104–27.

—— ‘Translation and Cultural Nationalism in the Age of Elizabeth’, Journal of the History of Ideas, 30 (1969): 593–602.

Hosington, Brenda, et al. Renaissance Cultural Crossroads. http://www.hrionline.ac.uk/rcc.

Lathrop, Henry Burrowes. Translations from the Classics into English from Caxton to Chapman, 1477–1620 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1932).

Matthiessen, F. O. Translation: An Elizabethan Art (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1931).

Morini, Massimiliano. Tudor Translation in Theory and Practice (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006).

Winny, James, ed. Elizabethan Prose Translation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1960).