UNTIL quite recently, George Gascoigne was the most neglected of the earliest Elizabethan writers, despite being hugely influential in his own time. In the twentieth century, his most successful authorial persona, the Reformed Prodigal, had come to dominate discussion of his work, casting him principally as a moralist and making him extremely unfashionable. But in the last quarter of the sixteenth century, Gascoigne was known as a successful courtly poet and performer, and an important innovator in many literary forms. His most substantial prose works were translations and would have formed a relatively minor part of his literary reputation. Nonetheless, it is his prose work which informs Gascoigne’s reputation today.

George Gascoigne’s modern reputation rests principally upon four works: the prose fiction A Discourse of the Adventures passed by Master F.J., one of the earliest important texts in the history of the novel in English; his prose play Supposes, a source for Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew; his frequently anthologized poem, ‘Gascoignes wodmanship’; and ‘Certayne Notes of Instruction concerning the making of verse or ryme in English’, the earliest essay on English composition. Three of these works—prose fiction, prose comedy, and poem—belong to just one of his books, A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres (1572/3), and the fourth, the essay, was added in its revised edition, The Posies (1575).1 But Gascoigne experimented in many genres, with both medieval, native English forms and avant-garde continental forms. He influenced almost every writer who followed him: his medievalizing influenced Spenser, and Master F.J. was a source for Sidney’s Arcadia. He wrote a news pamphlet (The Spoyle of Antwerpe), a medieval dream vision (Complaynte of Phylomene), and even the earliest English blank verse (The Steele Glas), a highly self-conscious pitch at literary fame. Gascoigne also had a crucial role in hybridizing the sonnet: the Italianate form originally imported by Wyatt and developed by Surrey was further developed by Gascoigne before Sidney, Spenser, Shakespeare, and ultimately every other writer of note took it up in the 1590s.2

The present essay seeks to consider Gascoigne as a prose writer. Of the four works that usually define his current reputation, three have significant prose elements: Master F.J. is partly prose and partly verse; Supposes is a prose comedy; and ‘Certayne Notes of Instruction’ is a prose essay on the art of versification, cast as a letter, one of several fictive letters in Gascoigne’s oeuvre. But the sheer range of Gascoigne’s prose work—fiction, drama, essays, letters, reportage, moral tracts, and translations from Latin, French, and Italian—is remarkable.

In this period, prose was often as tightly controlled and full of rhetorical devices as any verse form. Gascoigne does not discuss the uses of prose per se in ‘Certayne Notes’, where one might expect it, nor indeed elsewhere. He only uses the word ‘prose’ three times in all of A Hundreth and, where he does, he is not necessarily making the expected distinction between verse and prose: for example, he twice refers to A Hundreth as prose, whereas it is a mixture of prose and verse.3 Gascoigne contrasts verse and prose only once, in a short poem, ‘Gascoignes Epitaph uppon capitaine Bourcher’, where he asks ‘Can no man penne in metre nor in prose,/The life, the death, the valiant acts, the fame …/Of such a feere as you in fighte have lost?’ (p. 300). On occasion, Gascoigne’s choice of prose in itself allowed innovation: for example, he translated Ariosto’s I Suppositi (using both the prose and verse versions) into the prose Supposes. As Lois Potter notes, this allowed him to introduce an improvisational element which belonged at the time to Italian acting, rather than to writing: ‘His use of prose enabled him to insert the symbol “&c” at a few points, meaning that the actors were free to improvise, in the Italian manner, if they wished.’4 The flexibility this introduced was, arguably, a step towards the more natural cadences later captured in iambic pentameter on the English public stage. Given his fearless and often audacious experimentation across all generic boundaries, it seems fair to conclude that Gascoigne would use whatever style or formal element would best suit his poetic invention.

Gascoigne’s prose fiction, A Discourse of the Adventures passed by Master F.J., is a hugely significant text and characteristically innovative: only William Baldwin’s Beware the Cat (1570) pre-dates it as a work of original prose fiction in English. Gascoigne’s editor, G. W. Pigman, identifies Master F.J. as a ‘prosimetrum’ (mixing verse and prose), comparing it with Boethius’s De consolatione philosophiae, Dante’s La vita nuova, and Sannazaro’s Arcadia.5 Nonetheless, Master F.J. is widely recognized as highly innovative and it has inspired the best Gascoigne criticism of recent years. It was published in two versions within two years and its role in each of the collections of work in which it appears adds to the complexity of its status: different sets of prefatory letters in each volume construct two distinct fictions of publication for the work in which this early English prose fiction is published.6

Master F.J. was first printed in Gascoigne’s anonymous anthology A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres (1573), his first publication. Gascoigne had been writing poetry since the early 1560s and cultivated a reputation as a writer and translator at least since his return to Gray’s Inn in 1565. But his move into print in 1572/3 was undoubtedly prompted by his persistent financial difficulties and the need to display his many skills in the hope of gaining a new patron. Having deposited much of the material for his book with the printer, Henry Bynneman, Gascoigne left England for a second tour as a mercenary in the Netherlands, serving on this occasion under Sir Humphrey Gilbert.7 Gascoigne’s absence from London for much of the printing process is very important. Bynneman shared the printing of A Hundreth with another printer, Henry Middleton. Adrian Weiss argues that confusion caused by the division of the job between the two printers meant that the volume did not appear in the form Gascoigne intended, with the two plays placed after the letter from the printer and before the prose fiction.8 Significantly, Gascoigne was to become a diligent reader of printer’s proofs, making him the earliest English author known to check proofs daily.9

The disordering of the prefatory matter in the printing of A Hundreth is significant in understanding Master F.J., one of its principal items, and helps to explain why the volume was reissued with largely cosmetic revisions just two years later. The three prefatory letters should have been printed together immediately in front of Master F.J., at the front of the volume, and so forming a preface for the entire volume. These letters are ostensibly from the Printer (A.B.), the publisher (H.W.), and the editor/narrator, G.T., supposed friend of F.J. and the rest of the ‘sundrie gentlemen’.10 Arranged in this way, the prefatory material would have introduced a fictive circle of anonymous writers to whom the loosely defined ‘Discourse’ of Master F.J. and the subsequent miscellany of poems, ‘The Devises of Sundrie Gentlemen’, were attributed. The ‘Devises’ would then lead into the section attributed to one ‘George Gascoigne’, the only named author in the volume. It is little surprise that without the supervision of its author the plan failed, for this would have been a superbly witty volume, with a highly sophisticated, self-referential structure, the like of which had never been attempted before.

This sequence of letters, poems, and prose fiction posits a fictive literary circle outside the text, with which its main fictional character, F.J., is associated. The narrator, G.T., who is supposedly F.J.’s friend and confidant, claims to have been given a collection of poems in manuscript, the writings of F.J. and his friends, including ‘George Gascoigne’. G.T. has taken it upon himself not only to assume the role of narrator and editor, but then to pass the manuscript to one H.W., an established publisher, to have it printed. Susan C. Staub notes that in Master F.J., G.T. refers to his source, F.J., ‘no less than seventy times’, a technique which insists on the ‘reality’ outside the text and is sustained through the volume.11

This extended fiction of reluctant publication was to become an over-familiar trope for ambitious new authors, but when Gascoigne used it in this witty and structural way it was still thoroughly innovative. It is no surprise that Master F.J. was misread as autobiographical: the mixture of reality (Gascoigne as an aspiring author) and fiction (F.J., G.T., and the literary circle, the fictive publisher et al.) was just too sophisticated, especially given the additional confusion caused by the printers’ disruption of the sequence.

Three years later, Gascoigne created a similar fiction about the publication of another work, in a prose prefatory epistle for Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s Discourse of a Discoverie for a new passage to Cataia (March 1576). Gascoigne claims that he had visited Gilbert, his former colonel, at his home in Limehouse that winter, and says he was shown some of Gilbert’s writing, including the Discourse in manuscript:

The which … I craved at the saide S. Humphreys handes for two or three dayes to read and to peruse. And hee very friendly granted my request, but still seming to doubt that therby the same might, contrarie to his former intention, be Imprinted.

And to be plaine, when I had at good leasure perused it, & therwithall conferred his allegations by the Tables of Ortelius, and by sundrie other Cosmologicall Mappes and Charts, I seemed in my simple judgement not onely to like it singularly, but also thought it very meete (as the present occasion serveth) to give it out in publicke. Wherupon I have (as you see) caused my friends great travaile, and mine owne greater presumption to be registred in print. (Cunliffe, II, p. 564)

Gilbert’s Discourse was cast as a letter to his brother, but it was in fact a proposal for investors in a mercantile expedition to find the fabled north-west passage to China (Cataia). It was published to promote Martin Frobisher’s first expedition in search of the north-west passage in June 1576.12 This expedition was backed financially by a number of leading courtiers, notably the Earl of Leicester, and it is this connection which explains Gascoigne’s involvement in that particular fiction of publication.

Of the two versions of Master F.J. the first is generally considered superior. It is a loosely structured story told in letters and poetry, held together by the prose commentary of G.T., a highly opinionated narrator who mediates the reader’s understanding and acceptance of the events he is reporting. A young man, F.J., visits a country house in ‘the north partes of this Realme’ and becomes involved with Elinor, the wife of his host. Elinor already has a lover, her Secretary, who sets up the affair by answering F.J.’s first love letter on her behalf. Shortly after the first letters are exchanged, the Secretary leaves on an extended journey and, during his absence, the young F.J. becomes Elinor’s lover, consummating the affair one night in the Gallery of the house. Their relationship has an observer, a jealous unmarried woman called Fraunces, and in the background are Elinor’s husband and a number of unnamed courtiers. The inexperienced F.J. celebrates the affair with a sonnet celebrating his success at cuckolding Elinor’s husband, but this is an ironic turning point: the Secretary soon returns and F.J. becomes ill through his jealousy (an inset narrative translated from Ariosto). There is a slightly scurrilous literary game led by an older female courtier, Dame Pergo, in which the courtiers exchange stories. When Elinor visits F.J. privately in his room he tells her about his jealousy and suspicion. Elinor reacts angrily and the intimate moment turns quickly into a rape. Following this, Elinor unsurprisingly rejects F.J. and resumes her relationship with the Secretary. The remaining plot revolves around F.J.’s doomed attempts to regain Elinor’s favour and Fraunces’s rather cruel delight in observing them. The story ends rather inconclusively, when G.T. comments that ‘It is time now to make an end of this thriftlesse Historie, wherein although I could wade much further … Yet I will cease, as one that had rather leave it unperfect than make it to plaine’ (p. 215).

The lack of distinct boundaries between the fictive framework and the fiction is one of the most effective means by which Gascoigne blends fiction and reality. In his prefatory letter G.T. introduces the fictive literary circle by saying that he obtained ‘sundry copies’ from F.J. and ‘sundry other toward young gentlemen’ and that he has ‘set in the first places those which Master F.J. did compyle’. At the end of Master F.J., G.T. continues:

Now henceforwardes I will trouble you no more with such a barbarous style in prose, but will onely recite unto you sundry verses written by sundry gentlemen, adding nothing of myne owne, but onely a tytle to every Poeme, wherby the cause of writing the same maye the more evidently appeare: Neyther can I declare unto you who wrote the greatest part of them, for they are unto me but a posie presented out of sundry gardens, neither have I any other names of the flowers, but such short notes as the aucthors themselves have delivered therby if you can gesse them, it shall no waye offend mee. I will begin with this translation as followeth.’ (p. 216)

In this way, the narrative of Master F.J. is linked to the next section, ‘The Devises of Sundrie Gentlemen’, in which G.T. continues to provide the (much briefer) prose links between the poems. One of the most interesting aspects of this first version is the way it is recessed into the controlling fiction by which the present manuscript—all of A Hundreth—has been published by G.T. without the permission of its supposed several authors, the ‘sundrie gentlemen’. In this way G.T. sustains the controlling fiction of multiple authorship and characteristically seeks to provoke the reader’s curiosity about the identity of the supposed authors of the ‘Devises’.13 His assurance that ‘if you can gesse them, it shall no waye offend mee’ encourages the reader to ‘gesse’ and confirms that the game of identifying the author(s)—begun in the prefatory letters—is an important sub-textual device in the underlying scheme of A Hundreth.

The use of such controlling structures was widespread in Italianate experimental prose fictions: one could cite the storytelling games which unite Chaucer’s group of pilgrims, or Boccaccio’s and Marguerite de Navarre’s parties of nobles. In the same spirit, Gascoigne peoples A Hundreth with plausible figures from the nascent world of literary publishing—H.W. as the publisher, G.T. as an aspiring editor and narrator, and F.J. and his circle of friends (‘sundrie gentlemen’, as well as ‘George Gascoigne’) as the group of young writers whose work he publishes without their consent. This extended fiction was so successful, and so original, that Master F.J. seems to have been read as though it were actually factual and autobiographical. Gascoigne himself mocks (and denies) such credulous readings in the revised edition, whilst conspicuously failing to quash speculation—and even, to some extent, provoking more (the most likely authorial representation is Bartello, a fictional Italian author to whom the tale is ascribed in the revised edition, as we shall see). Later generations, too, have devised a remarkable range of possible biographical readings.14 The entire ‘Discourse’ is so dense with literary devices and figures, both familiar and entirely new in 1572/3, that it could almost be an exercise in literary inventiveness. It takes its gossipy narrator and framing fiction (the literary circle) from the Italianate novelle; its inset prose narratives are from romance, while the story of F.J.’s Suspicion is a translation of Ariosto’s tale of Sospetto; and Pergo’s exchange of stories is taken from courtly love, as is much of the situation of F.J. and Elinor’s affair. But it is easy to see why, when Gascoigne blurs the boundaries between fiction and reality so thoroughly, so many critics have suspected that the tale had some basis in real events.

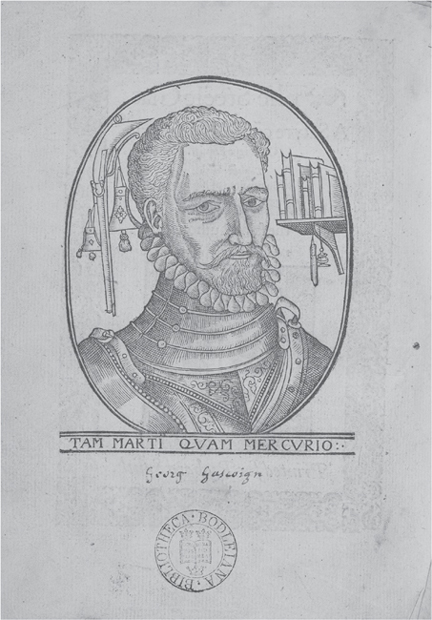

When Gascoigne returned to England in 1574/5, it seems that he was embarrassed by the state of his first published book and perhaps by some of the conjectures which surrounded it. The entire volume, including a revised version of Master F.J., was published in a revised and extended edition under Gascoigne’s own name as his Posies (1575). It is in this volume that Gascoigne first fully developed the persona of the ‘Reformed Prodigal’, although he had used it much earlier, during his days at Gray’s Inn.15 Nonetheless, it is in the Posies that Gascoigne first adopted a unified authorial persona, complementing it with what would become his invariable motto in works which bore his name: ‘Tam Marti, quam Mercurio’ [‘As much for Mars as for Mercury’], which identified him as a soldier-poet, like Turberville, Churchyard, Googe, and Riche.

Essentially the same material is rearranged into ‘Floures to comfort, hearbes to cure, and weedes to be avoyded’, but Gascoigne also added substantial new prefatory material. The controlling fiction of the literary circle is abandoned and the whole collection is acknowledged as Gascoigne’s. His new prefatory letters group his readers into ‘reverend Divines’, ‘al yong Gentlemen’, and ‘the readers generally’, but these divisions allow him to enact different aspects of his ‘Reformed Prodigal’ persona and it is unlikely that he expected his readers literally to select and read only the preface which applied to them. Together, these letters defend his publication of A Hundreth and set up an alternative extended fiction of publication by which an apparent scandal caused by the contents of Master F.J. directly gave rise to the reissue of the volume as the Posies:

I understand that sundrie well disposed mindes have taken offence at certaine wanton wordes and sentences passed in the fable of Ferdinando Jeronimi, and the Ladie Elinora de Valasco, the which in the first edition was termed The adventures of master F.J. And that also therwith some busie conjectures have presumed to thinke that the same was indeed written to the scandalizing of some worthie personages, whom they woulde seeme therby to know. (pp. 362–3)

If some readers had indeed raised suspicions that Master F.J. was based on real events—and we have only Gascoigne’s own assertion that this was the case—then it is characteristic that even in this revised edition he seems to provoke speculation at the same time as apparently trying to quash it. For there are other texts in the Posies which seem designed to provoke speculation about its relation to reality, including the completed version of ‘Dan Bartholmew of Bathe’ and the new sequence of poems on the Greene Knight, ‘The Fruite of Fetters’, which are encoded autobiography and are connected in turn to ‘Dulce bellum inexpertis’, which is overtly autobiographical.16 Clearly, a subtext is being constructed by which the alert reader is led to identify all these personae with Gascoigne himself. But as Bartholmew is the name of one of his personae, then he is most plausibly represented by Bartello, ‘he which writeth riding tales’: both in the bawdy tales such as Master F.J. and the riding tales such as ‘Gascoignes Memories’, which he composed while ‘riding by the way’ (p. 282). And if Gascoigne is indeed Bartello, that does signal both versions of his tale as original prose fiction.

The loss of the Stationers’ Register for 1570–5 is a significant disadvantage, as this would have provided the most reliable external evidence of any censorship of, or official action against, the text. In fact, fifty copies of the revised edition, the Posies, were seized by Her Majesty’s Commissioners on 13 August 1576, when the bookseller Richard Smith returned ‘half a hundred of Gascoignes poesies’ to the Stationers’ Hall.17 There has been much speculation about the exact level of censorship for these kinds of publication in the period, but if Master F.J. had indeed caused some comment, it may (to use Cyndia Clegg’s admirable phrase) have been censured rather than censored. Certainly, Her Majesty’s Commissioners’ action against the Posies did not impact upon Gascoigne’s other activities, as he published the Delicate Diet just three days before the seizure, and just two weeks later he was sent by Lord Burghley secretly to Paris. As Clegg concludes, ‘what was censurable in 1573 was revised and became acceptable in 1575, and what was acceptable in 1575 became censorable in 1576 … the text changed minimally, but Gascoigne’s status and the climate of reception changed substantially’.18 This remains the most persuasive explanation, highlighting the contingent and pragmatic attitude to authorial control operated by Her Majesty’s Commissioners.

The key objection to the notion of a real scandal, apart from the complete lack of any corroborative evidence, is the limited revision which took place, for Master F.J. is largely unchanged: if any ‘worthy personages’ had indeed been scandalized then Gascoigne would not have been suffered to reissue the tale. Of the revisions which were imposed, some changes, most notably losing the gossipy, biased narrator G.T., serve actually to make the story less sympathetic. The tale is relocated to Italy and firmer formal boundaries are imposed, so that it becomes a ‘fable’ rather than a ‘discourse’ of ‘adventures’: this is ‘The pleasant Fable of Ferdinando Jeronomi and Leonora de Valasco’. But of course, Italy was by reputation the very home of dissolute living and passionate affairs, so although the change does situate the narrative more firmly in the continental prose tradition, and specifically the Italian novelle, this is at best a morally ambivalent relocation. The relationships between characters are more defined than in Master F.J., so that Leonora (Elinor) is married to the ‘heyre of Valasco’ and Frauncischina (Fraunces) is ‘the elder daughter of the lord of Valasco’, making the two women sisters-in-law. Gascoigne seems to resist even this nominal relocation by quickly reverting to his characters’ original English names. The lord of Valasco has invited Ferdinando (F.J.) to his castle with the particular intention of engineering a match with Frauncischina. Both these changes make Ferdinando’s offence against his host a more obvious abuse of his hospitality. The cuckolding sonnet is cut and the rape scene is abbreviated, but little else has been done to ameliorate the moral shortcomings of the tale. Most obviously, Gascoigne’s conclusion is hardly typical of a ‘fable’:

[Ferdinando] tooke his leave, and (withoute pretence of returne) departed to his house in Venice: spending there the rest of his dayes in a dissolute kind of lyfe: and abandoning the worthy lady Frauncischina, who (dayly being gauled with the griefe of his great ingratitude) dyd shortlye bring hir selfe into a miserable consumption: whereof (after three yeares languishing) shee dyed: Notwithstanding al which occurrentes the Lady Elinor lived long in the continuance of hir acustomed change … (p. 216)

The injustice of this conclusion subverts the overtly moralistic purpose of the fable as a genre: the foolish and dissolute Ferdinando learns nothing and pursues a ‘dissolute kind of lyfe’; the apparently virtuous woman Frauncischina falls ill and dies; and the unreformed, promiscuous Leonora continues to enjoy her succession of lovers.

The ways in which Gascoigne mixed genres and styles and played on and with generic expectations in both Master F.J. and the Fable influenced many of the important writers of the 1580s, 1590s, and beyond. Robert Maslen and others have argued that Master F.J. became a model for Sidney’s Old Arcadia.19 Katharine Wilson has explored its influence on Thomas Nashe, Robert Greene, George Whetstone, and John Grange.20 It also influenced George Pettie and Barnabe Riche, as well as Thomas Deloney, John Lodge, and John Lyly. Nonetheless, Gascoigne’s Master F.J. would not have formed the most important part of his literary reputation to his contemporaries, and did not do so until the twentieth century, when the dominance of the novel in literary culture threw it into prominence and it became the work upon which his place in modern literary history principally rests.

In 1575, the most significant addition to The Posies was ‘Certayne Notes of Instruction’, an essay which seeks to describe the principles of composition in English. Just as Master F.J. influenced Sidney’s Arcadia, so ‘Certayne Notes’ influenced Sidney’s Defence of Poesie (wr. 1579–80) and the subsequent Elizabethan attempts to lay down rules for English composition, both descriptive and legislative. Even James IV of Scotland (the later James I of England) is thought to have been influenced by Gascoigne’s essay.21 Indeed, ‘Certayne Notes’ is widely recognized as the first critical essay in English. Its rhetorical structure and possible sources have been well studied and its significance was recognized very quickly. As well as Sidney, writers such as Webbe and Puttenham, sensing the flowering of English letters with the enrichment of the language and the increasing number and facility of literary forms, took up the idea of attempting to write down the rules or instructions for English versification. For example, William Webbe acknowledges and quotes from ‘thys course of learning to versify in Ryme’ (I. 275), in his highly influential Discourse of English Poetry (1586).22

‘Certayne Notes’ is cast as a letter to another fictive Italian, Signor Eduardo Donati, and because the essay is cast as a letter it again requires a degree of characterization in the author: ‘Signor Edouardo, since promise is debt, and you (by the lawe of friendship) do burden me with a promise that I shoulde lende you instructions towards the making of English verse or ryme, I will assaye to discharge the same, though not so perfectly as I would, yet as readily as I may …’ (p. 454).

Jayne Archer finds support for the general view that Edouardo Donati was a fictive name in the probable allusion to Ælius Donatus, the Roman grammarian and author of the Ars grammatica, which would have been extremely familiar to Elizabethan schoolboys.23

Gascoigne is even more witty and playful than Sidney, using irony and humour liberally, and quickly subverting the rules he does articulate. For example, he proposes self-contradictory rules such as ‘eschew straunge words, or obsoleta et inusitata’ (p. 458). Even in his fictive framework, Gascoigne subverts the whole notion of laying down ‘notes of instruction’ with his observation that ‘Quot homines, quot Sententiae [so many men, so many minds], especially in Poetrie’ (p. 454). This is not to say that Gascoigne’s essay is not serious, or that it does not have a serious purpose. Its very existence indicates Gascoigne’s literary ambition: it is a significant step towards elevating English letters to the status of true literature, the classical writers in Latin and Greek. This is the context within which his anti-inkhorn sentiment should be seen. Gascoigne was a very competent Latinist, but he is, typically, slightly ahead of his generation in recognizing the potential for English to become itself a literary language. He was himself a liberal coiner of words, derived from both Latin and native, Anglo-Saxon vocabulary. The Oxford English Dictionary lists 173 of Gascoigne’s neologisms (‘corn-fed’, ‘indecorum’, ‘gardening’), as well as 544 existing words which he used in new ways, creating new meanings.24

The single most revealing point Gascoigne makes in the ‘Certayne Notes’ is his very first assertion about the foundation of poetic creativity: ‘The first and moste necessarie poynte that ever I founde meete to be considered in making of a delectable poeme is this, to grounde it upon some fine invention’ (p. 454). This invention needs to be founded upon what he calls ‘aliquid salis’ [‘some wit’]: ‘By this aliquid salis I meane some good and fine devise … what Theame so ever you do take in hand, if you do handle it but tanquem in oratione perpetua, and never study for some depth of devise in the Invention, and some figures also in the handlyng thereof: it will appear to the skilfull Reader but a tale of a tubbe’ (p. 455). Although inventio is traditionally the first of the five points of formal rhetoric, Gascoigne’s idea of invention extends across the entire content and presentation of his works.25 It is possible to understand almost all of Gascoigne’s work in light of this emphasis on poetic invention: his compulsive experimentation, his range of literary activities and styles, and above all perhaps his attitude to authorship, for Gascoigne habitually developed an authorial persona appropriate to each work, under which he presented it to his readers or audience. Thus in ‘Certayne Notes’, he adopts the persona of a courtly gentleman, friend of the Italian gentleman with the punning surname, Edouardo Donati; whereas in the Posies as a whole, he presents the volume under the persona of the Reformed Prodigal, an ostensibly moralistic persona.

This ‘depth of devise’, then, extends to the prefatory and in some cases illustrative material which accompanies the literary work, and it may be that the relative neglect in criticism of such apparatus contributed to the more general misreading of Gascoigne’s work in the twentieth century. Prefaces and dedications were seen as ‘non-literary’ and therefore entirely separate, even optional, parts of a work; and yet, in an age of patronage, the circumstances of literary production, and how those circumstances are presented, must be significant to the work itself. For if the letters in the Posies are read as being literally addressed to the ‘Reverence Divines’, or ‘al yong Gentlemen’, rather than as performances of selected aspects of the authorial persona, the Reformed Prodigal, then the entire volume makes less sense: this is not the thoroughly expurgated and moralized edition of A Hundreth that it claims to be. Or if the self-portrait in the frontispiece of the Steele Glas/Complaynte of Phylomene (Fig. 10.1) is not recognized as being a self-portrait, it cannot be seen to form a part of the overarching invention of the theme of reflectiveness in that volume: both mirror as metaphor, as figurative tool for estates satire and self-examination, and as the practical means to create a self-portrait.26 That theme encompasses the Complaynte of Phylomene, too, recast as a dream vision, another medieval form for self-examination. Without recognizing the theme of reflectiveness as a witty unifying concept for the volume, it becomes less comprehensible, less accessible, and its achievement is diminished. Gascoigne’s ‘Certayne Notes’, then, articulates the core creative principle of much of his work. In the same way, it is possible to see the extended fiction of the publication of A Hundreth as the ‘fine Invention’ upon which the volume was based.

Shortly after he published the Posies, Gascoigne came to the Earl of Leicester’s attention when his translation of the Noble Arte of Venerie was published. He participated in Leicester’s entertainments at Kenilworth Castle and again later on that summer’s Progress at Woodstock. Gascoigne rose rapidly in both royal and courtly favour, especially within Leicester’s circle of patronage. He was then invited to join in the presentation of gifts to the Queen at New Year 1576, producing the manuscript of Hemetes the Heremyte, which he had performed at Woodstock, with its famous frontispiece illustration showing him kneeling before Elizabeth. The prose tale of Hemetes is not Gascoigne’s: it was most probably written by the host at Woodstock, Sir Henry Lee, as it carries with it several concealed agendas which would benefit Lee and his coterie.27 What Gascoigne adds to Lee’s tale is the prefatory and illustrative material and the three translations, into Latin, French, and Italian. The prose preface reveals Gascoigne’s own agenda. He is aiming for courtly preferment and demonstrating his fitness to serve the Queen in whatever capacity she sees fit: ‘Yor matie shall ever finde me wth a penne in my righte hand, and a sharpe sword girt to my left syde … willing to attend yor person in any calling that you shall pleas to appoynt me’ (p. 477). Gascoigne’s translations demonstrate practical language skills and his facility with French, in particular, would be taken up later in the year by Lord Burghley, who sent him to Paris and on to Antwerp. On his return, he again demonstrated his credentials as a soldier-poet by writing and publishing another important prose work, the official public account of what happened when the Spanish soldiers occupying Antwerp mutinied and ran amok.

Gascoigne’s The Spoyle of Antwerpe is one of the earliest examples in English of reportage, since the events which it records happened only three weeks before it was printed in London (including the nine days it took to travel back from Antwerp).28 The Spoyle is far from an impartial account, even though at times Gascoigne is as critical of the complacency of the Dutch as he is of the cruelty of the Spanish. It was, however, an officially sanctioned version of events, published anonymously but ‘seene and allowed’ and probably issued for its propaganda value. Eleanor Rosenberg, in her study of Leicester’s patronage, concludes that Gascoigne’s account ‘accurately reflects the ambivalence of Elizabeth herself and most of her Privy Council’ towards events in the Netherlands, but that it is predominantly anti-Spanish and so ‘served their purpose well enough’.29

FIGURE 10.1 George Gascoigne, self-portrait, The Steele Glas and the Complaynte of Phylomene (1576), frontispiece

The Spoyle, despite Gascoigne’s claims that it is a ‘true report’ (p. 590), reveals a considerable amount of rhetorical structuring and formal organization. It is typical of a ‘book of news’ in being both factual and exemplary, 30 but its generic register is mixed: Gascoigne incorporates a humorous prose narrative describing his trip on foot through the midst of the fighting, from the English House where he and the English merchants had taken refuge, towards the castle, where the most intense fighting was. He clearly signals this as a change from ‘credible report’ to eyewitness account: ‘…let me also say a litle of that which I sawe executed’ (p. 594). But what follows is the most obviously structured section of the whole pamphlet: it opens with a set piece dinner at the English House at the height of the battle, during which a report is brought in of a ‘hote scarmouche’ in progress at the Castle. Gascoigne went up to a high point in the house, from where he could see fires had broken out ‘in fower or five places of the towne, towardes the castleyeard’, so he took his cloak and sword and ventured outside to see ‘the certainty thereof’ (p. 594). As he got closer to the Castle, passing over the Bourse, Gascoigne says he saw a ‘great trowpe’ coming towards him (pp. 594–5) and his description of his excursion quickly degenerates into slapstick as the crowds

bare me over backwardes, and ran over my belly and my face, long time before I could recover on foote. At last when I was up, I looked on every syde, and seeing them ronne so fast, began thus to bethinke me. What in Gods name doe I heare which have no interest in this action? synce they who came to defend this towne are content to leave it at large, and shift for themselves: And whilest I stoode thus musing, another flock of flyers came so fast that they bare me on my nose, and ran as many over my backe, as erst had marched over my guttes. In fine, I got up like a tall fellow, and wente with them for company: but their haste was such, as I could never overtake the[m] …(p. 595)

The absolute symmetry of being knocked over first onto his back and then onto his front shows a considerable amount of formal shaping. Gascoigne’s physical courage is not, however, in doubt: he actively defended the Governor of the English merchants, Sir Thomas Heton, when the English House was attacked.31 He turned his experience into this comic episode, another instance where Gascoigne creates an unexpected shift of register in his prose.

The sheer range of Gascoigne’s prose work is extraordinary. His longest prose works, however, are all translations. He translated his Gray’s Inn play Supposes (and the verse Jocasta) from Italian in 1566, but he was also fully fluent in Latin and French and published prose translations from all three languages. But it is often his presentation—the prefatory material, the illustrations, or the added poems with which he frames the prose element—which enrich his source most. His anonymous Noble Arte of Venerie or Hunting (June 1575) is a translation from the French of a very up-to-date manual of hunting, Jacques du Fouilloux’s La Venerie.32 Gascoigne added three original illustrations showing Elizabeth hunting; and poems expressing the point of view of the hunted animal. The Noble Arte was produced as one of a pair of volumes by the bookseller Christopher Barker, alongside George Turberville’s Booke of Hauking, specifically targeted at a courtly readership.33

By contrast, Gascoigne’s Droomme of Doomesday (May 1576), is a very long, dry collection of prose translations of three moralistic Latin tracts for the Earl of Bedford, done primarily to support his Reformed Prodigal persona and to counter his reputation as a profligate. Gascoigne offers Bedford, a well known and devoutly religious literary patron, a conciliatory and penitent ‘Gascoigne’. Once again, in his prose dedication, Gascoigne offers a narrative version of how the work came to be written:

I was (now almost twelve moneths past) pricked and much moved, by the grave and discreete wordes of one right worshipfull and mine approved friend, who (in my presence) hearing my thryftlesse booke of Poesyes undeservedly commended, dyd say: That he lyked the smell of those Poesies pretely well, but he would lyke the Gardyner much better if he would employe his spade in no worse ground, then eyther Devenitie or morall Philosophie. (Cunliffe, II, pp. 211–20)

There is no more probable candidate for ‘one right worshipfull and mine approved friend’ than Bedford himself, being no more than polite about the revised Posies and actually being critical of Gascoigne’s choice of frivolous subjects. In response, in his dedication, Gascoigne offers his least equivocal performance as the Reformed Prodigal: ‘…I finde my selfe giltie of much time mispent, & of greater curiosite the[n] was convenient, in penning and endyghting sundrie toyes and trifles’ (p. 211).

Indeed, the keywords in Gascoigne’s dedicatory epistle are authentically Protestant, and include (moral) Reformation, Zeal, Duties, and Profit, as well as authentically courtly, including Desert and Desire.

A similar technique is evident in his much shorter prose translation of another moralistic Latin tract, A Delicate Diet, for daintiemouthde droonkardes (August 1576). In both the Droomme and the Diet, Gascoigne created an aptly moralistic authorial persona under which he offered his work to a potential patron. Gascoigne not only produced these prose texts strategically, but marketed them too, making overt connections between his moralistic titles. A reader picking up this slim bundle of papers at the bookseller’s stall would be directed to the Droomme by Gascoigne’s assertion at the beginning of the Diet that he came across its original, an epistle by Saint Augustine, 34 as he was working on the Droomme: ‘Whyles I travayled in Translation, and collection of my Droomme of Doomes daye: and was busyed in sorting of the same (for I gathered the whole out of sundry Pamphlets:) I chaunced at passage, to espye one shorte Epistle, written against Dronkennesse’ (p. 455). I argue elsewhere that Gascoigne seems to have deliberately produced two distinct portfolios of work: the work he presented under his Reformed Prodigal persona and published under his own name, and the more courtly work which he published anonymously, thus preserving the integrity of this ‘George Gascoigne’, the Reformed Prodigal. It is one of the primary functions of Gascoigne’s prose prefaces and letters that they create a forum for the performance of whichever authorial persona Gascoigne wishes to present his work. In the autumn of 1576, then, while Gascoigne’s courtly stock was very high, he also published a series of moralistic titles under his own name using his ‘Reformed Prodigal’ persona. He was to pursue his courtly success with perhaps his most audacious performance so far when he presented another manuscript work to Elizabeth at New Year 1577.

Whereas Gascoigne had presented the illustrated manuscript of Hemetes to Elizabeth in 1576, his manuscript of The Griefe of Joye was entirely plain, except for the gold leaf which highlighted every mention of the Queen’s name. Every aspect of this work is carefully designed to remind Elizabeth of Gascoigne’s successful mission to Antwerp in the summer and in his prose dedication he claims that he is presenting the work: ‘that I might make youre Majestie witnesse, how the Interims and vacant howres of those daies which I spent this somer in your service have byn bestowed’ (p. 514). He even refers specifically to Antwerp in the Second Song, ‘The vanities of Bewtie’ (2, 32). The underlying invention in the Griefe of Joy is that ‘the leaves of this pau[m]phlett have passed with mee in all my perilles’ (p. 514). Although the fine condition of the manuscript, and the gold leaf highlights, are not the result of being carried inside a man’s doublet for three weeks or more, it is designed to look like an unfinished work, breaking off in mid-stanza with a dramatic flourish: ‘Lefte unperfect for feare of Horsmen’.35 The most striking aspect of the work, though, is how readily Gascoigne casts himself as Elizabeth’s own court poet and gives a name to his courtly poet persona. Among the list of courtly ladies in the Second Song is ‘Ferenda Natura’, linked specifically to ‘my banishment to Bathe’ (2, 23) (referencing his autobiographical poem Dan Bartholmew), who addresses Gascoigne’s courtly poet persona as ‘Bartholmew’. This network of allusions refers the reader back to the revised edition of Master F.J., the Fable, and illustrates how his witty approach to realism and self-invention runs through his work, both in verse and prose.

On the same date as his manuscript of the Griefe of Joye, Gascoigne wrote and illustrated beautiful manuscript letters ‘to al my Lordes and goode frendes in Cowrte’.36 Only his letter to Sir Nicholas Bacon, his relative by marriage, survives. Gascoigne’s courtly success was evidently still proving more expensive than remunerative and he was once again in urgent financial need. The letter to Bacon includes an emblematic device of a man about to mount a horse, as well as a self-deprecating verse about how Gascoigne has had to learn to restrain himself, making ‘reason’ his ‘rider’. The emblem and verse complement the prose letter:

But (my good Lorde) my colltyshe and jadishe trickes have longe sithens broughte me owte of fleashe, as withowte some spedye provysione of good provender I shall never be able to endure a longe jorneye, and therfore am enforcede to neye and braye unto your good Lordship and all other which have the keye of Her Majesties storehowse, beseachinge righte humblie that you will voutchsaffe to reamember me with some extreaordynarye allowaunce when it fallethe.

Gascoigne’s prose vividly expresses his conceit: the underlying invention of the starving horse is brought into sharp focus by how consistently it is applied across illustration, verse, and prose. This letter and the Griefe of Joye comprise Gascoigne’s last known literary works. He died in November that year, a profligate talent in innovative literary forms in both verse and prose.

Austen, Gillian. George Gascoigne, Studies in Renaissance Literature, 24 (Woodbridge: D. S. Brewer, 2008).

Cunliffe, J. W., ed. The Complete Works of George Gascoigne, 2 vols., vol. II (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1907, 1910; repr. New York: Greenwood Press, 1969).

Heale, Elizabeth. Autobiography and Authorship in Renaissance Verse: Chronicles of the Self, Early Modern Literature in History (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003).

Pigman III, G. W. George Gascoigne: A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

Prouty, Charles T. George Gascoigne:. Elizabethan Courtier, Soldier, and Poet (New York: Columbia University Press, 1942, repr. 1968).

Wallace, William L. George Gascoigne’s The Steele Glas and the Complaynte of Phylomene: A Critical Edition with Notes, Salzburg Studies in English Literature, Elizabethan and Renaissance Studies, 24 (Salzburg: Institut für Englische Sprache und Literatur, University of Salzburg, 1975).

Weiss, Adrian. ‘Shared Printing, Printer’s Copy, and the Text(s) of Gascoigne’s A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres’, Studies in Bibliography, 45 (1992): 71–104.