‘… the English Tongue… as it contains a greater stock of Natural and Mechanick Discoveries, so it is also more inrich’d with beautiful Conceptions, and inimitable Simlitudes, gather’d from … the Works of Nature’.1

SEVENTEENTH-century scientific prose is a haunted house. Various remarks by Francis Bacon, if read in isolation from the rest of his opinions, sound inimical to the uses of the imagination, particularly rhetorical tropes and figures, but also literary genres. That his position, and that of the early modern discourse of science as a whole, was anything of the kind has been rehearsed too often by modern critics.2 But Bacon’s pronouncements are undeniably beset by apparent (though not actual) contradiction and inconsistency that, in their turn, have produced the myth of Bacon’s call to dismiss rhetoric wholly in favour of a plain or somehow de-rhetoricized language of science and scientific expression.3 This misunderstanding of his ideas (and his own literary habits) ignores the elaborate rhetorical practice of his most fervent followers, natural philosophers and historians like Thomas Browne, Robert Boyle, Margaret Cavendish, and Walter Charleton, to name only a few. The traditional account of natural philosophy’s ‘defeat’ of rhetoric by Baconian diktat elides a number of things: it ignores the fact that post-Baconian natural philosophical writing of the seventeenth century has remarkable and unusual rhetorical and imaginative features; and that these were eagerly discussed by the natural philosophers, both in their science and in lay topics; that they all came to science, as Bacon himself did, from the intensely rhetorical humanist training of the grammar schools, universities, and Inns of Court;4 and that, as Peter Harrison notes, the traditional structure of a ‘natural history’ included all the categories of the humanist curriculum, including rhetoric and poetry.5 It would, in other words, be contra naturam if scientific practitioners themselves were not rhetorically adventurous and adept, or if scientific practice, theory, training, and results were not rhetorically dense, imaginatively suggestive, and often formulated in verse, plays, elegies, inscriptions, and utopian essays. There are too many examples of such literary science to require proof; instead, we can attempt to understand the scientific view of the literary by noticing what practising early modern scientists said on the subject.

In 1667 Thomas Sprat paraphrased Francis Bacon on the use of scientific similes: ‘The Comparisons which [experiments] may afford will be intelligible to all, becaus they … make the most vigorous impressions on mens Fancies.’6 Such claims for metaphor and other analogical figures were part of a vigorous debate, largely unresolved, among early modern natural philosophers seeking an appropriate expository style for their experiments, essays, and observations. A presiding need to reform the nature of knowledge according to the directly observable made the choice of scientific expression a peculiarly weighty matter—early modern science had to correct the mistakes of the ancient authorities and to cast off the shackles of scholastic philosophical quibbling, as well as the humanist addiction to the arts of language, all in order to establish the primacy of res above verba. The vexed problem of how to ‘do’ science was not just an empirical one, but required fresh address to the ways in which the doing of science could be made account of. Even though a rhetorical regimen for early modern science was first discussed in depth by Francis Bacon in The Advancement of Learning and the Parasceve, and demonstrated by him in New Atlantis and Novum Organum, there was no default convention or format for presenting matters of fact—natural historians and philosophers published their findings in many genres—and early modern science is marked by a profusion of literary forms and trials. Agreement about which of these might best serve science had not been reached (nor was it even gradually emerging) by the time of Boyle’s death in 1691 and the coexistent ‘literary technologies’ of science available in the seventeenth century are accordingly varied.7 A striking and universal feature of scientific writing, however, is its interesting and often uneasy relation to rhetorical tropes, narrative structures, and figurative language.

Because Bacon’s various remarks seem difficult to reconcile, his supposed hostility to figurative language as an appropriate mode for investigative truth was also poorly understood by some early modern Baconian scientific practitioners, and by their associates, and has been reiterated by the historians of that practice. Thomas Sprat, for example, in his influential, but only marginally authoritative History of the Royal Society, asserts that rhetorical ornament is ‘a thing fatal to peace and Good Manners’ and indicative of civil disorder, 8 apparently extending a proper scientific regard for perspicuous language into an official horror of any sort of eloquence and strategically ignoring Bacon’s own utopian fiction of a scientific society in New Atlantis. But Bacon’s hostility is chimerical: although he had insisted that needlessly elaborate rhetorical ornament is ‘a distemper learning’, 9 he also judged that ‘whatsoever science is not consonant to presuppositions, must pray in aid of similitudes’ (in other words, new ideas may require analogies where no appropriate terms exist).10 And Sprat himself understood this balance perfectly well when he paraphrased Bacon on experiment as a source of fruitful analogy—‘experimental comparisons’ invigorate the imagination. Other scientific voices seem similarly inconsistent: Robert Boyle claims categorically that rhetoric is an ‘obnoxious’ art, 11 yet also says that ‘proper comparisons do the Imagination almost as much Service, as Microscopes do the Eye’, citing not only ‘the Illustrious Verulam’ as a model and sanctioning authority, but even ‘that severe Philosopher Monsieur Des Cartes [who] somewhere says that he scarce thought, that he understood any thing in Physiques, but what he could declare by some apt Similitude’.12 William Petty, the statistician and founder-member of the Royal Society, opposed tropes and conceits, but nevertheless produced a dialogue on shipping celebrating his scientifically engineered (and repeatedly unsuccessful) design for a catamaran.13 Although John Evelyn complained of the neo-Latin jargon of contemporary scientific writing by the logodædali (‘cunning in words’), he was himself an enthusiastic coiner, the originator of ‘coniferous’, ‘impermeable’, ‘toxic’, and many others.14 Even the notoriously severe Hobbes was not quite absolute in his repudiation of the ornate: ‘reason and eloquence … may stand very well together’, he said in Leviathan, with the qualification ‘(though not perhaps in the naturall sciences, yet in the Morall)’.15 Margaret Cavendish, typically quirky, explains that her atomic poems are presented in verse precisely because ‘Poets Write most Fiction, and Fiction is not given for Truth’: her theory of matter, probably erroneous she admits, will better pass in that guise.16 This was certainly not the reasoning employed by other natural philosophers defending imaginative writing: they tended to argue for enargeia (or rhetorical vividness) because it clarified scientific ideas, not because it disguised their doubtfulness. Boyle closely rehearses Philip Sidney’s defence of enargeia and the poetic images that convey it when he urges ‘shining examples’, rather than ‘precepts or grave discourses’, and says, in a close paraphrase of the Defence, that ‘to condemn Figurative and Indirect ways of conveying ev’n Serious and Sacred matters, is to forget How often Christ himself made use of Parables’.17 Despite the criticisms of a few particularly splenetic (and non-scientific) critics like Robert South and Robert Crosse, and the exceptional practice of natural philosophers with special interests in the philosophy of language or in mathematics like John Wilkins, Isaac Newton, and John Locke, 18 the scientific writers of the mid- and late seventeenth century were deeply attentive to the possibilities of rhetoric and of the rhetorically assisted and stimulated imagination as the way to precise and perspicuous expression of matters of experimental and observational fact.

The long-standing Platonic mistrust of any writing that is rhetorically ornamented or is a species of fiction—that it is a mere imitation of a reality, which is itself no more than a shadowed form of the Ideal; that poetry is thus an imitation of a fake19—informed a general uneasiness about the rhetorical and structural artifices of the literary; this uneasiness is apparent everywhere in early modern culture, in the arts, religious practice, and inductively and experimentally produced scientia. It is this unease that Philip Sidney was answering in his Aristotelian riposte when he argued in the Defence of Poetry that the poetic has the highest capability of expressing universal truth. It is this counterargument that might be said to undergird the widespread early modern willingness to employ the poetic to express the scientific.

Likewise, it is this unease that prompted Wilkins to propose, in An Essay towards a Real Character (1668), that ignis fatuus of early modern Neoplatonism, a purely denotative, perfectly conceptual language. This is an extreme and unworkable response to requirements of perspicuity, and far more typical are continuing ruminations by scientists on the use of vernacular rhetoric to convey natural-philosophical fact. Bacon, as Brian Vickers reminds us, ‘gave considerable thought to the forms in which he and others should communicate their ideas and discoveries. His concept of language was not monist, a single form of discourse which would always be the same in whatever context.’20 His pronouncements on language do not, as a result, suggest an a priori disaffection from its powers, but rather the opposite, a just recognition and admiration of its capabilities, and a commensurate concern about its misappropriation or impropriety.21 In this, Bacon has a far more liberal view of the imagination and of poetry, imagination’s special genre, than has sometimes been recognized by modern commentators, or by the seventeenth-century ones;22 but he is always careful to insist on a decorum in designating the proper rhetorical mode for specific kinds of scientific writing. In Parasceve, his prefatory and preparatory introduction to Novum Organum, for example, the third aphorism dismisses all ornaments of speech, similitudes, and elegance in general from natural and experimental histories (by which he means works like Sylva Sylvarum, of gathered but ‘indigested’ data on which true natural philosophy is to be based23). To admit such elegancies, he concludes in a beautiful similitude, is as much as to organize the tools in a shipbuilder’s shop for visual, rather than practical effect.24 And yet, he also claims in De Augmentis, the process of ‘inventing’ (in its older sense of ‘discovering’) knowledge must be accomplished by similitude.25

Bacon argues that there are rhetorical registers and proprieties to be observed in the writing of science. In a natural ‘history’, where raw data await construction into axioms by natural philosophers, the rhetorical and the poetic are supererogatory; but in propounding these empirically derived axioms to a wider, less learned, public, tropes allow the abstract to become visible and comprehensible. Bacon’s argument here is as much as to say that tropic, illustrative language allows the philosopher, after establishing a general truth from observables, to paint ‘the outward beauty of such an axiom’. Thus, when Cowley praises Bacon’s programme in his ode ‘To the Royal Society’, he can commend Bacon’s vindication of eloquence and wit from ‘all Modern Follies’ (merely superfluous eloquence), and in the same stanza describe his ‘candid Style like a clean stream’, both views compassed within a poem that imagines natural philosophy as a captive prince fed too long on the sweetmeats of scholastic discourse, and Bacon as a Moses leading his people into the promised land of new learning.26 This complex Baconian amalgam of tropic practice and anti-tropic claims is neither self-consuming nor inconsistent, nor did it ruin or demote poetry in the pre-Enlightenment. It reflects instead Bacon’s own measured, and essentially social, sense of linguistic use and propriety across various kinds of natural-philosophical expression, his designation of unfigured and plain style for the gritty, learned work of establishing philosophical truth, and of a more poetically free style for the promulgation of that securely established truth to a general audience.

Competing with this Baconian tendency towards rhetorically complex and variously registered natural philosophy was a robust anti-Ciceronian element characterized in England by Hobbes, who partly derived it from the Mersenne circle in which he had moved while in France.27 Inspired by Tacitus and Sallust, and associated with the Senecan ideal of unadorned and plain language—quod quae veritati operam dat oratio, inconposita esse debet et simplex (speech that deals with the truth should be unadorned and plain)28—and latterly with Lipsian epistolary precepts of dynamic and rhetorically unhampered expression, it was a style intended to be penetrating and even disconcerting in its directness and perspicuity, quite unlike the regular and shapely elegance of Cicero’s periods and rhythms.29 Bacon’s Essays might be the most obvious example in English of the anti-Ciceronian; and yet, his theoretical writings advocate a middle way between the plain and the figurative, each mode approved in their proper roles. He himself wrote in both styles. As Stephen Clucas has observed, the Baconian instauration required ‘forensic rhetorical investigation of the scientific field of knowledge’ and yet, it had to grapple with ‘the seemingly insoluble problem of instituting a scientific discourse which did not lay rhetorical claims to authority’.30 The rhetorical could neither be allowed as the end, or the shaping impulse, of scientific discourse, nor could it be permitted to overwhelm reason in its appeal to the imagination; but its power could be profitably, if carefully, harnessed to promote the power of that discourse. In understanding the range of rhetorical practices and rhetorical philosophies available to the natural philosopher, therefore, we must resist any absolute division between reason and eloquence merely as the fiat mainly of later voices; at the time, only Comenius and certain other radical puritans thought of the literary as the absolute antagonist of the scientific or the utilitarian.31 This Baconian openness issues in a rich tradition in which science is promulgated and discussed (and even satirized) in travel writing, exposition, epistles, dialogues, essays, fables, aphorisms, and verse of all kinds.32

Even his works of essentially or ultimately spiritual purpose—Religio Medici, UrneBuriall and The Garden of Cyrus, and A Letter to a Friend—betray Thomas Browne’s scientific cast of mind: matters of faith or of morals are very often speculatively investigated, not only as if they were experimental assays, but these thought-experiments are couched in similitudes of the empirically investigated natural world. Religio Medici considers resurrection in terms of the behaviour of mercury; Urne-Buriall revolves mortuary customs, an apparently anthropological topic, with an eye to sanitary measures and the effect of climate and soil upon decomposing flesh; The Garden of Cyrus, often dismissed as a slightly crackpot exercise in arbitrary signification (the figures of five to be found throughout the creation), might also be understood as a botanist’s field investigations into plant structure and vegetable germination that turn out to have this unexpected common parameter; and A Letter to a Friend adduces meaning from the death of an accomplished young man partly through the evidence of dissection and medical case histories.33

In 1649, only three years after the first edition of Pseudodoxia Epidemica, the often preposterously florid and Latinate Walter Charleton singled out Browne (with Bacon) as a ‘Heroicall Wit’ whose English honoured ‘the Majesty of our Mother Tongue’, whose prose was ‘spun as fine and fit a garment, for the most spruce Conceptions of the Minde to appear in publick in, as out of any other in the World’, and who disabused the Scholastic claim that ‘Latin is the most symphoniacall and Concordant Language of the Rationall Soule’.34 The symphonic quality of Browne’s majestic English we readily recognize in spiritual works like Religio Medici and Urne-Buriall. The more directly natural-philosophical works, however, show how an equivalent (though adapted) linguistic richness presents in Browne’s scientific habits of prose, especially in Pseudodoxia Epidemica (1646–72). Unlike Bacon and Boyle, however, Browne never laid out his views of scientific style explicitly and his ideas must be worked out by indirection, through the evidence of his practice.

In discussing authoritative ancient natural historians in Pseudodoxia, Browne included the ‘elegant [hexameter] lines’ of Oppian (Halieutica (on fishing) and Cynegetica (on hunting) that can be read ‘with delight and profit’, and he regrets that modern neglect of this writer ‘reject[s] one of the best Epick Poets’ (PE I.viii.51).35 He also complains, however, that certain ancient ‘Moralists, Rhetoricians, Orators and Poets’ relied too much on ‘invention’, simile, and other illustrative tropes:

to induce their Enthymemes unto the people, they took up popular conceits, and from traditions unjustifiable or really false, illustrate matters of undeniable truth. Wherein although their intention be sincere, … yet doth it notoriously strengthen common Errors, and authorise Opinions injurious unto truth. (PE I.ix.54)

In other words, Browne theoretically approves of the poetic in natural history, but he is compelled to disparage merely rhetorical (‘enthymemic’) instead of empirical arguments as less true and unfortunately more persuasive. Elsewhere, this careful discrimination allows him to advocate a mixture of literary conventions: the writer should affect a plain and unembellished style, and yet, one which, if not fully Ciceronian, will not offend Ciceronian stylists; he should have little recourse to strange or foreign words, and yet, he is to use esoteric or even homespun (domi nata) terms when necessary. He is not to allow mere fluency to overwhelm meaning, but let the language match the subject.36 These heavily qualified, undogmatic opinions may explain the mixed features of Browne’s prose in his mature works, and the nature of his revisions of Pseudodoxia over the course of four editions illustrates this ample approach to style. Rarely, in any of his works, does he resort to elaborate conceits, and he was apparently not much interested in the Baconian fable. But as for ‘invention’ of a more local and contained kind—especially similes and metaphors—some of his most memorable aphoristic formulations are wonderfully tropic: ‘heads that are disposed unto schism … do subdivide and mince themselves almost unto atoms’ (RM I.8); ‘to flourish in the state of glory we must first be sown in corruption’ (GC Letter); and ‘the long habit of living indisposeth us for dying’ (UB 5). As T. W. Westfall, Reid Barbour, and others have noted, Browne adjusted his great encyclopaedic work on error to reflect his growing sense of the power of language to illuminate and to distort matters of fact.37 He is scrupulous, for example, to show how much care must be expended in lexical choice, as when, in a discussion of the flooding of the Nile, he digresses on the foolish use of absolute superlative designations for ‘things of eminency in any kinde’, designations which are casually made simply to mean ‘eminent’, rather than ‘pre-eminent’, but semantically seem to insist on a unique attribute when ‘there being but one in every kinde, their attributions are dangerous’ (PE VI.viii.497). He uses this observation to weave a wide-ranging list of counter-examples from natural and civil history—the relative sizes of the ‘greatest’ cities, from Rome to Cathay, the relative smallness of the ‘smallest’ birds from the European wren to the American hummingbird, and the relative height of the ‘highest’ mountains from Olympus to Cotopaxi (PE VI viii.497). And he is willing to extend this history of semantic error into an ‘illation’ (an inference or a conclusion) of our inability to know God, the true superlative. This is a useful example, not just of Browne’s attention to linguistic propriety; it also shows us how in a work apparently so much more strictly ordered than the rhapsodic Urne-Buriall or Garden of Cyrus, he is willing to let his thinking, like the Nile itself, and like his rhetoric, occasionally o’erflow the measure of his notional subject. For Bacon, the ‘problem’ of rhetorical choice is that where it can sometimes illustrate it can also distract. For Browne, the very act of attending to the amplitude and variety of language applied to the investigative subject is itself investigative, an enactment of the ‘thinking’ of science.

Although the fundamental linguistic decision that preceded and governed the choice and execution of style—to write in more inclusive English, rather than in more exclusive Latin38—needed justification in the preface, Browne himself promoted Latinate English prose in, among other things, his enormous number of neologisms ‘beyond mere English apprehensions’ (PE, ‘To the Reader’, 2–3) (more than 800 according to the OED; and more than twice that many new uses of existing words). The competing titles of his great work—the official mouthful, Pseudodoxia Epidemica, and the rather more homemade Vulgar Errors—frame the Anglo-Latinate situation in which Browne and other natural philosophers found themselves, ‘mak[ing] claims upon a language which that language [was not] prepared for’.39 Thus, he recognizes the value of both plainness and of esoteric terms; he denigrates those who are constitutionally incapable of understanding figurative, tropic language; he loves paradox, copious, resonant figures of speech, and, above all, similitudes. In his carefully pliant sense of linguistic propriety, Browne refines and extends the straightforward Baconian antitheses of plainness and eloquence. It is a pliancy he inaugurated in his famous apology for the pirated 1643 edition of Religio Medici, in which he asked his readers to understand his work in the ‘soft and flexible’ tropic sense in which it had been offered.40 The excuses for Religio Medici, a spiritual autobiography, not a scientific work, are unnecessary in Pseudodoxia, where the oscillation between Latinity and the vernacular, between the figurative and the unadorned, are unapologetically on display.41 His revisions of the work show that he was moving towards a more immediate and sometimes sparer style; and it is certainly different from the more gorgeous styles of Religio Medici and The Garden of Cyrus.42 But in Pseudodoxia Browne can write of Satan’s attempts to seduce our understanding with falsehoods as ‘but Parthian flights, Ambuscado retreats, and elusory tergiversations, whereby to confirme our credulities …’ (PE I x.64), a sentence in which a glorious Latinate copia is to the fore. His aim in the prose of science can hardly be to pare it down to the theoretical denotative quality enjoined by Sprat and Wilkins. As Barbour puts it, ‘his pursuit of a more streamlined, less erudite and florid style … did not cancel the beauty or vitality of his prose; rather, various styles interacted with one another in a complex dialogue’.43 In Pseudodoxia, we might say, the rhetoric of science is as extensively, if differently, elaborated as in any of his meditative, rhapsodic works.

In the preface to Pseudodoxia Browne asserts ‘wee are not Magisteriall in opinions, nor have wee Dictator-like obtruded our Conceptions, but in humility of Enquiries … have only proposed them unto more ocular discerners’ (PE, ‘To the Reader’, 4). He criticizes the qualifications of certain ancient authors who ‘write dubiously [hesitatingly], even in matters wherein is expected a strict and definitive truth, extenuating their affirmations with quod aiunt, fortasse, saepe aut numquam’ (‘as they say’, ‘probably’, ‘often or never’, ‘sometimes’) (PE, I.vi.34).44 But it is a rhetorical gambit he himself constantly uses when he forbears certainty with a conditional phrase (‘were there any such species’) or states a received idea with litotes (‘it is not without some question’). Such qualifications are semantic indications of his unmagisterial intentions, themselves arising out of his modesty in the face of the creator (‘as his wisdom is infinit, so cannot the due expressions thereof by finite’ [PE, VI.v.468]). This is not to disagree with Kevin Killeen’s characterization of Browne’s project in Pseudodoxia as ‘grand and ambitious’, 45 but rather, to frame that grandeur of undertaking in the prose of the lapsarian condition.

This limiting sense of lapsarian understanding is the same that informs Bacon and Boyle’s disinclination for treatises and systems (‘a great impediment to natural philosophy’ [Proemial, 3]), says Boyle, who prefers ‘the usefulness of Writing Books of Essays’ to convey the fragmentary state of knowledge (Proemial, 7). The entire structure of Pseudodoxia is additionally qualified by Browne’s revisions over the four editions during his lifetime and by the way in which he regularly transgresses the boundaries of his own stated topics, as if emphasizing the fluidity of enquiry. This is especially true of what I have elsewhere described as ‘establishing’ or heuristic essays, ones that lay out evidence ab initio, as if for a Baconian natural history, and then proceed to conduct scrutiny of it, rather than setting out to correct an existing error with existing information.46 A case in point is the chapter ‘Of the Cameleon’ (an amalgam of the establishing and the corrective essay format), a discussion initiated by the commonplace that the chameleon lives on air alone. This essay is a typical example of the way Browne moves with ease between classical and modern authorities, between literary and scientific evidence, between data about the designated topic and contingent, but distinct material. His citation of authorities for and against this view refers to the usual suspects in natural history—Aristotle, Pliny, and Solinus for the ancients; Peiresc, Vizzanius, and Bellonius for the moderns—but also to Ovid and Homer. He explains a functional teleology of animal anatomy: chameleons have stomachs, ergo they must eat since ‘the wisdom of nature abhor[s] superfluities, … effecting nothing in vain’ (PE, III.xxi.243). He is given to duplicating couplets in which a Latinate hard word is paired with an elucidating (though not always precisely synonymous or more familiar) word—verisimility/probable truth, aggeneration/conversion, incrassation/corpulency, unctuous/full of oyle, pellucid/transparent, jejune/limpid, latitency/hibernation, inspiration/drawing breath, or phlegmatick/cold—a practice that would smack of learned condescension unless it is understood as another kind of qualification, a recognition that expressions in natural philosophy neither dare be complacent or finite nor yet pretend to absolute authority. But Pseudodoxia sets out not simply to examine an episodic series of errors, but rather to pursue the ‘Encyclopædie and round of knowledge’ (PE, ‘To the Reader’, 1), a heroic attempt. Of this intellectual balance between authority and humility, Killeen remarks that it belies ‘the common characterisation of Browne in the role of a modest, error-by-error Baconian field-worker, clearing away the undergrowth of nonsense, with a mixture of good sense and empirical competence. Browne’s reconstruction of knowledge is grander and more ambitious than it is often taken to be. Pseudodoxia scrutinises, or at least skirts, that most burning of issues—the nature of knowledge in a postlapsarian world.’47

Another enactment of the infinity of nature is Browne’s open-ended, tessellating process of revision, addition, deletion, and adjustment made over a quarter-century, the refining of certain expressions, adding or deleting information as it became available or obsolete, all aimed at a gradual amendment of what Bacon had called ‘a knowledge broken’.48 It is, to use a chemical metaphor, an alembication of knowledge and of style, of refining the image of an emerging order.49 For example, in ‘Of the Cameleon’ he adds remarks on the discovery of ‘seminall principles’ and ‘vital atoms of plants and Animals’ in rainwater (no doubt based on recent developments in microscopy in the 1660s); he omits passages about lizards and frogs; he restores a correct etymology he had disparaged in the first edition (PE, III.xxi.244); and his assumptions about the role of the liver in digestion is finally adjusted in the 1672 edition in the light of his reading of Harvey (PE, III.xxi.244).50

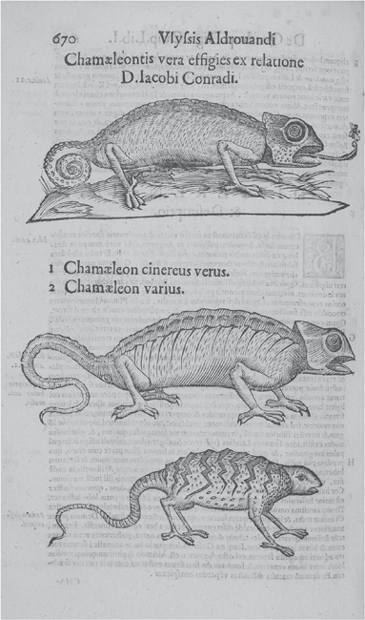

FIGURE 17.1 Chameleon, in Ulisse Aldrovandi, De Quadrupedibus Digitatis Oviparis (1637), p. 670

One of the most striking features of the chameleon essay is the substantial digression in the middle of it, which, by the 1672 edition, is very nearly half the length of the whole chapter. This digression, which arises from the consideration of the chameleon’s purported air diet, abandons that creature almost entirely to revolve the nature of air and water as aliments, the nature of aliments in the body, how fire uses air, how ignition and flame are caused and sustained, and the presence of micro-organisms in rain-water. All these are significant areas of enquiry that had been experimentally addressed in this period by Harvey, Lower, Boyle, and Hooke, and discussed in recent works by Liceti, Littré, Jorden, Power, Kircher, and others; it is hardly surprising to find Browne clearly au fait with recent developments. What is striking is how certain données of a traditional reliance on report and authority give way in the course of the chameleon chapter to observable, experimental findings by ‘more ocular discerners’ who have wholly or in part seen chameleons or investigated digestion and respiration directly. And Browne’s purpose in Pseudodoxia is precisely that—to move the reader, via an establishing error, into a newer and more immediate world of investigated fact. The digression, which concludes with a few remarks about the nutrition of mythical animals such as the wind-bred mares of Spain and Ariosto’s account of Rabican, a horse born from air and flame, gives way to real animals again, but this time with Browne’s authoritative evidence from his own observations and experiments. ‘We have made a trial’ of the sustenance of reptiles, he says; ‘we have included’ snails in glass to see if they can live without food; ‘observations are often made’ in winter, when many animals are hibernating, a seasonal variation that affects conclusions about metabolic activity. The final shape of the chameleon essay is, in other words, the shift from the received to the observed, both in his textual references and in his concluding remarks about his own observations and experiments; and from the chameleon—exotic, not exactly mythical, but certainly unavailable in northern latitudes—to the metabolic organization of animals in general; and finally, via a few genuinely mythic instances, back to the chameleon itself (Fig. 17.1).

Unlike Bacon before him or Boyle after him, Browne is not unduly preoccupied with linguistic propriety in science, but only because (we sense that) for him that debate is answered by his own practice and a carefully exercised rhetorical array of English lexis and idioms. Was Browne simply operating at ease on ground smoothed by Bacon and his contemporaries, or does Robert Boyle’s return, in the middle of Browne’s literary career, to nervous considerations of style represent the actual state of the field?

‘Apposite comparisons’, said Robert Boyle, are ‘a kind of argument’ (CV [A6r]), and ‘wont to be more acceptable than any other to our modern virtuosi’ (CV [A2v]). Boyle, even more than Bacon, was obsessed with the propriety of scientific style and was even more voluble than his predecessor on the subject, whom he referred to as ‘that great Ornament and Guide of Philosophical Historians of Nature’, and whose authority he often claimed when making pronouncements on scientific style.51 Although he claimed to prefer the ‘more reall Parts of Knowledge … hated the study of Bare words’, he was temperamentally of a ‘poeticke strain’, 52 one that prompted a full-blown Christian romance (The Martyrdom of Theodora and Didymus) and let him cast a large number of his scientific works as dialogues with distinct, named characters, or as isogogic epistolary essays and familiar letters addressed to the romantically named young men Pyrophilus and Lindamor.53 Had he not been seduced by natural philosophy in his early twenties and already given to somewhat prim moralizing, Boyle might well have made his mark as a purely imaginative writer like his brother, the romance-writing Earl of Orrery. His early letters betray a powerful, and self-conscious, narrative gift; Philaretus itself is a highly shaped romance;54 ‘Accidents of an Ague’ has strong generic and thematic similarities to Donne’s Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions; and Occasional Reflections is a series of moralized observations, often of natural phenomena, addressed to ‘Sophronia’ (his sister, Lady Ranelagh), and very strongly influenced by Bacon’s advocacy of fable.55 He defended what he called ‘luxuriant’ writing as ‘pictures drawn (with Words instead of Colours) for the Imagination’ (OR a3[r]), especially suited to the young and the unlearned who might not otherwise attend, but also useful to virtuosi; he was careful to excuse ‘uneven’ writing as a reasonable decorum in casual compositions; and he promoted the dialogue as a fit vehicle for philosophical ideas—his own practice was ‘to imagine two or three of my Friends to be present … and to make them discourse as I fancy’d Persons, of their Breeding and tempers, would talk to one another on such an Occasion’(OR a1[r]–2[r]).

In an unpublished manuscript of 1647, Boyle employed Sidney’s brimstone-and-treacle metaphor of the poetic (i.e. imaginative and/or rhetorical) ornament, so memorably employed in the Defence: as Sidney claimed that to read good fictions is to ‘see the form of goodness (which seen they cannot but love) ere themselves be aware, as if they took a medicine of cherries’, 56 so Boyle renders this quality of moral romance as ‘Sugar to the Pill: ’tis no Part of the Pill, but yet ’tis that without which the Pill wud scarce be swallow’d down’.57 Boyle says that his rhetorical training instilled ‘a very cautious & considerate way of expressing himselfe’, 58 and the persistent tendency to discuss or apologize for style and structure in later works suggests that he remained keenly sensitive to tonal effects and generic propriety, that he was concerned with narrative structure, the status of fictional interventions, and the reception of his work by a very particular audience, whom he hoped to influence in an overtly Sidneian manner by ‘rendring Virtue Amiable’ to those who are more moved by ‘shining examples … than by dry Precepts and grave Discourses’.59

Although Philaretus is an equivocal conversion narrative (conversion from the imaginative to the devotional in a highly rhetoricized format), it was, significantly, written at the moment when Boyle is said to have undergone a quite different conversion, from the moral to the scientific. This shift, which Michael Hunter, Lawrence Principe, and others have characterized as a ‘Great Divide’, 60 took Boyle away from the writing of improving works of ethics and devotion (such as Aretology, Theodora, and the germ of what would become Seraphick Love), which he framed in the Sidneian/Horatian mode of inducement ‘of well-doing and not of well-knowing only’, 61 and towards investigative writing, for which he had largely to invent his own new forms. These forms were not stable over the whole of his literary career and he returned to certain genres (for example, the dialogue) on different occasions, even as he was developing an essentially new narrative style of experimental essay.62 The variety of these forms, and his willingness to use them at need, suggests a literary sensibility open to the particular strengths of different genres and modes. As well as the dialogue, Boyle wrote familiar epistles, isagogic letters, a romance, autobiography, essays, formal correspondence, and, of course, the full-blown treatise.

In his eulogy of Boyle, Matthew Morgan writes somewhat clumsily of Boyle’s reputation as unusually literary: ‘He in Philology was profoundly Vers’d,/Poets and Orators fluently rehears’d;/He never them superfluously did quote,/But a new piece of Knowledge to promote …’63 Boyle was also approved by other scientists for his understanding of ‘the true use and signification of words whereby to register and compute … conceptions’.64 Robert Codrington’s Latin ode in praise of Boyle declared him ‘not of a more noble genealogy than a literary one’.65 Indeed, Boyle’s style was so distinctive, so civilly mannered (even fussy at times in its careful polite discriminations and literal definitions) that Samuel Butler dubbed it a ‘trillo’ (an embellishment) and pastiched Boyle’s often maddeningly prolix style in an ‘occasional reflection’ about Walter Charleton trying out ineffectual ‘mortiferous unguents’ on dogs and kittens before the Royal Society.66

Although Boyle moved from moral to natural-philosophical studies in about 1649, he nevertheless maintained a clear hereditary line from Sidney, the primary example of English moral heroic romance, in stating the purposes of the imaginative in scientific writing. In the moral work Seraphick Love (partly written in 1648; later completed and eventually published in 166367) he is unequivocal about his fictionalizing of a pious example and frankly intends to claim the freedom of most writers, ‘who scruple not in Popular Composures to make Similes and Allusions grounded on Popular Traditions and Perswasions’.68 The liberal use of simile is one of the most striking features of Boyle’s style in Seraphick Love and he is particularly inclined to use the processes of the laboratory and the observatory in this way, as when he applies a ‘chymical metaphor’ of purification in the furnace to the indiscriminate consumption of human life, the virtuous and the vicious together, in public calamities, 69 or when he divides ‘seraphic’ from ‘common’ lovers as astronomers are divided from children, the former concerned with what the optic glass reveals in the heavens, the latter diverted merely by the gilded decorations on the outside of the tube.70 Seraphick Love, written just at the juncture of Boyle’s literary career as a moralist and as a scientist, is a hybrid of moral purpose kitted out with similitudes of the laboratory and of the practices of observation.

In Occasional Reflections (1665) (a work that includes the eponymous essays, the chronologically organized ‘Accidents of an Ague’ and ‘Angling Improv’d to Spiritual Uses’) Boyle makes a survey of several key aspects of ornament. Similitudes are ‘perhaps no great Vanity’ when they provide the natural philosopher with comparisons (OR a3[r]), and ‘Truths and Notions that are dress’d up in apt Similitudes, pertinently appli’d, are wont to make durable Impressions on [the memory]’ (OR b2[r]); decorum, he thinks, excuses any style as long as it is maintained (OR a[4r]); he judges it wiser to use contemporary examples for guidance on style than ancient ones, since it would be

improper to … have unadvisedly made Shepherds and Nymphs discourse like Philosophers or Doctors of Divinity [even though it is within the writer’s ambit to] introduc[e] any whom he represents as intelligent Persons; they may be allow’d[,] ev’n about things ordinary and Mean, to talk like themselves, and employ Expressions that are neither mean, nor ordinary (OR a[5r]).

He discusses protasis (in rhetoric a proposition, or the first half of a comparison) and notes the perils of over-amplification (OR a3[v]); and he is especially eloquent on the subject of descriptions, ‘[t]hese being but Pictures drawn (with Words instead of Colours) for the Imagination, the skilful will approve those most that produce in the mind, not the Finest Idaeas, but the Likest …’ (OR b2[r]). His aim in employing rhetorical, especially those descriptive and prosopopoeical, figures which produce images in the mind, is to ‘mak[e] almost the whole World a great Conclave Mnemonicum, and a well furnished Promptuary, for the service of Piety and Vertue …’ (OR b2[r]). Eloquent embellishments, he says,

I will not be forward to condemn … whether they be laid out upon Speculative Notions in Theology, or upon Critical Inquiries into Obsolete Rites, or Disputable Etymologies; or upon Philosophical Disquisitions or Experiments; or upon the florid Embellishments of Language; or (in short) upon some such other thing as seems extrinsical to the Doctrine that is according to Godliness, and seems not to have any direct tendency to the promoting of Piety and the kindling of Devotion. For I consider, that as God hath made man subject to several wants, and hath both given him several allowable appetites, and endowed him with various faculties and abilities to gratifie them; so a man’s Pen may be very warrantably and usefully emploi’d, though it be not directly so, to teach a Theological Truth, or incite the Reader’s Zeal. (OR V, 140–1)

This is the apodosis of a reflection whose protasis presents syrup of violets as a metaphor of useful eloquence, the colour, smell, and taste of it being grateful to the senses and yet, the concoction itself a purgative whose ‘good smell can expel bad humours’ (OR V, 140). Such remedies are effective in part because they offer ‘Allurements to make use of them’ (OR V, 140). Later in the same reflection he notes, as he did in Theodora, that what he calls ‘a Nicer sort of Readers … are so far from being likely to be prevailed on by Discourses not tricked up with Flowers of Rhetorick, that they would scarce be drawn so much as to cast their eyes on [serious writing]’ (OR V, 142). Although he is primarily concerned with pious writings in this passage, the special care he takes to notice that all kinds of writing, including the experimental and natural philosophical, can be rhetorically enhanced deserves notice: even at this early stage, when his concerns have been almost exclusively with moral expression, he is careful to allude to the special linguistic demands of the scientific.

Boyle tells the reader that his reflections are composed according to structure. Each reflection begins with an incident or phenomenon. This protasis is, he explains, ‘the Ground-work of all the rest’ (OR [A3v]), and he uses it to ‘ingage an Attention’, rather than ‘to confine my self to the Magisteriall Dictates of either Antient or Scholasticke Writers’ (OR [a5r]). A Boylean reflection thus commences with the incident of the title (‘Upon my Spaniel’s Carefulness not to lose me in a strange place’; ‘Looking through a Perspective-Glass upon a Vessel we suspected to give us Chace, and to be a Pyret’; or ‘Upon his Paring of a Rare Summer Apple’). Each protasis yields its apodosis, ‘an Application of what was taking notice of in the Subject … some important Moral instruction, or perhaps some Theological Mystery’ (OR [A6v]). The paring of an apple yields a reflection on ornament: the gaudy skin of the apple distracts us from the ‘true relish’ of the sound fruit as figures and tropes ‘so often conceal or mis-represent … the true and genuine Nature’ of moral discourse (OR I, 182). The reflections are moral essays; and yet, the protasis–apodosis structure is essentially an inductive one: it moves readerly consideration from the raw datum of the occasion of a spaniel wandering or keeping close to its master’s heels to a sublime and more general axiom about our tendency to forget God under distraction until some momentous event occurs to recall us to Him. Often the reflections hover at the edge of Boyle’s own experimental investigations. He has a glow-worm in a glass (protasis). ‘Rare Qualities may sometimes be Prerogatives, without being Advantages …’; ‘the light that ennobles him, tempts Inquisitive Men to keep him’ (apodosis) (OR V, 154–5). Elsewhere, his reflections and meditations include metaphors of distillation, perspective and burning glasses, the workings of physic, cloud formations, prisms, the composition of rainwater, magnetism, botany, and cabinets of curiosity. Occasional Reflections is a work that incorporates Boyle’s axioms of style, his practice of it, and a wealth of similitudes derived from his natural-philosophical studies, the whole work structured like a demonstration of Baconian induction. The structure of the reflections is nowhere explicitly defined that way by Boyle, although he does liken the ability of the reflector to extend large ideas in ethics and divinity from minor matters to the mathematician’s art of ‘giv[ing] us an exact account of all the Journeys [the sun] performs’ from local data (OR, 20).

Occasional Reflections shows us a Boyle focused on questions of style, and expressing himself frequently, as Browne did before him, in analogies with experimental practice and scientific theory. If the technologies of observation give him conceits for moral meditations, so too do the subjects of experimental investigation (why rain is not brackish though it originates from the sea; why cheese and vinegar are colonized by micro-organisms; or why a prism offers a theory of colours). Occasional Reflections complicates his rhetorical theory, too, by revolving the argument for and against rhetorical ornament. Reflection Six in Section II (‘Upon the sight of a Looking-glass, with a rich Frame’) is a dialogue spoken by three friends. The mirror’s frame stands, of course, for rhetorical elaboration of the plain image delivered by the mirror itself. Eugenius approves the elaborate frame because it enforces self-scrutiny by drawing us to the mirror; Lindamor agrees, but believes that ornament will only be rightly understood by the wise; Eusebius thinks it is distracting and deceptive (OR II, 199). Elsewhere, Eugenius refers to ‘a fancy of your Friend Mr Boyle, who was saying that he had thoughts of making a short Romantick story’ in the style of Utopia and New Atlantis (OR II, 199).

Boyle’s self-conscious sense of appropriate rhetorical register plays out in Occasional Reflections. He worries about ‘want of uniformity’ of style, regrets that some of the following meditations are ‘neglected’ or ‘luxuriant’ (OR B1[v]); he apologizes to the reader in Angling Improv’d to Spiritual Uses (Section IV of Occasional Reflections) for employing the dialogue, a form which might confuse the fictional and the actual by making the literary vehicle of the discourse seem ‘a Story purely Romantick’ (OR [b4v]). He excuses stylistic variation and flexibility through the nature of the subject: ‘this kind of Composures requires … a loose and Desultory way of writing’ (OR [B1r]). And yet, in excusing the plainness of some of his experimental writing, he remarks that ‘without allowing it any of those advantages that method, style, and decent embellishments, are wont to confer on the composures they are employed to adorn’, he will be thought to have failed to present the material properly.71

Very many of Boyle’s post-1649 scientific writings are cast in established literary formats (notably the dialogue, a form he knew at first-hand from the ‘familiar Kind of Conversation’ practised in his schoolroom days as a standard humanist genre;72 and the familiar epistle derived from Seneca). These later works make free with the expressive richness of highly honed humanist rhetoric; and they often dwell on the propriety of the literary in scientific expression. Ultimately, Boyle’s many scruples about romance and the value of rhetorical tropes and of the imaginative in general, as expressed in Philaretus, Seraphick Love, and Theodora and Didymus, were at least salved if not borne away entirely by the requirement of these very tools in forging a new language for natural philosophy later in his career.

Brian Vickers observes that ‘[E]xperiment … is itself a literary genre or rhetorical form’.73 This is clearly Boyle’s thinking and in the Proemial Essay he deliberates about an apt, decorous, and utile form for experimental report. As a good Baconian, he is especially critical of ‘systems’ that pretend to final authority and complete knowledge, and he advocates the essay instead because he requires a fragmentary literary genre for science, one whose style analogically enacts the incompleteness of the experimenter’s knowledge and prevents any readerly delusion of completeness.74 In support of his contention that systems impede natural philosophy, he constructs an elaborate experimental metaphor using an anecdote of a camera obscura he saw demonstrated in Leiden. When the aperture is small the picture cast on the wall is clear, but when a larger aperture is allowed to let more light in the chamber, the image disappears. By analogy, systems, when viewed in ‘a weak and determinate degree of light’, look plausible; however, ‘if but a full light of new Experiments and Observations be freely let in upon them, the Beauty of those (delightful, but Phantastical) structures does immediately vanish’ (Proemial, 8). He tells us that he carefully avoided the ‘contamination’ of systematic works by Bacon, Gassendi, and Descartes until he felt he had developed his own thinking securely—another instance of his preference for establishing fact ab initio, rather than receiving it from ‘authority’ (Proemial, 6). Boyle presents this essay as an isogogic letter (itself a trope) in which he proposes himself to his young friend Pyrophilus as a parabolic or didactic figure, much as he had done in Philaretus with its conversion narrative: although he considers that the Proemial Essay is written too early in his career, he cannot afford to remain silent on the subject, like the steward who buried his single talent rather than use it.

He is eloquent on the use of parables, and here, as in Philaretus, he makes an almost direct quotation of Sidney’s Defence.75 This same Boyle, on the other hand, also declares that essays should be written in a philosophical, rather than a ‘Rhetorical strain’, ‘rather clear and significant, than curiously adorn’d. Ornari res ipsa negat, contenta doceri [the subject itself needs no ornament; it is enough that it be understood].’ Needless rhetorical ornament in scientific writing (or ‘too spruce a style’), he goes on to assert, is like painting the lens of a telescope with delightful colours which hinder its correct use. Nevertheless—and here is another Boylean volte face—‘though it were foolish to colour or enamel upon the glasses of Telescopes, yet to gild or otherwise embellish the Tubes of them, may render them more acceptable to the Users, without at all lessening the Clearness of the Object to be look’d at through them’ (Proemial, 12). In other words, dull and insipid writing (a style he finds characteristic of many chemical writers) has a tendency to ‘disgust’ the reader and to work against the conveyance of truth; ornament will draw the reader to the correct apprehension of truth, and the natural-philosophical conceit of the telescope conveys this principle. Yet, in the same essay Boyle can insist its design is ‘only to inform Readers, not to delight or Perswade them’ (OR [a4r]). This apparent renunciation of the Horatian/Sidneian utile et dulce (so knowingly paraphrased in Philaretus), in comparison with his actual rhetorical practice in the Proemial Essay, is, however, hardly definitive: his narratives are structured to place the reader within the occasion of the experiment, ‘these being but pictures drawn … for the Imagination’ (OR [a4r]).

It may be that Boyle’s early commitment to moral philosophy and the struggle to find apt styles for it prompted his lifelong attentiveness to the writing of science, and generated the rhetorical diversity of his writings.76 The Sceptical Chymist (1661) exemplifies Boyle’s maturing use of literary trope as a tool of scientific discussion and adds the purely fictive account of experimental results to the genuine experimental narrative in which, in the words of James Paradis, ‘text became experimental action’.77 The work is a dialogue between the exponents of a Paracelsian, an Aristotelian, and a sceptic. Boyle’s own position is the last one, voiced in the dialogue by Carneades, and his purpose is to show that the two other chemical schools are not founded on evidence. But this is one of many occasions where Boyle’s scientific writing could almost be mistaken for a courtesy book. This is not surprising, given the careful explanation he makes of his generic selection: it is, he says, a book designed by a gentleman for gentlemen, ‘wherein only Gentlemen are introduc’d as speakers’. Such speakers will therefore speak a language ‘more smooth … Expressions more civil[,] than is usual in the more Scholastick way of writing…. whence perhaps some Readers will be assisted to discern a Difference betwixt Bluntness of Speech and Strength of reason, and find that a man may be a Champion for the Truth, without being an Enemy to Civility’.78 With these remarks he can denigrate an older, linguistically obsessed, and disputatious way of writing science that accompanied an outmoded way of doing science (Scholastic philosophy); insist on the social premium enjoyed by properly conducted modern (empirical) science; and do both in the medium of fiction.79

The setting of The Sceptical Chymist is highly specified, rather than notional, and takes nearly all of the first nine pages to establish—it is ‘a relation of what passed a while since at a meeting of persons of several opinions’, namely Philiponus (the Paracelsian), Themistus (the Aristotelian), Carneades (the sceptic), and Eleutherius (the neutral party who moderates the discussion). The occasion is detailed: although Boyle had another appointment, to consult with a friend who knows about furnaces, he is persuaded by Eleutherius instead to visit Carneades in his garden on a beautiful summer’s day, a vignette in which civility (to meet Carneades) is almost, but not quite overridden by the call of experimental science (to consult about furnaces). They find Carneades already seated in a bower with two other friends and Boyle is reluctant to intrude upon them, but Carneades ‘received [Eleutherius] with open looks and armes, and welcoming me also with his wonted freedom and civility, invited us to rest our selves by him …’ (SC 2–4). An elaborate narrative of civility precedes the dialogue proper—at one point, there are so many apologies and courtesies going back and forth between the various parties that Eleutherius has to remind them that their purpose is to exchange arguments, not compliments (SC 14). The purpose of all this, Boyle says at the beginning of the work, is to remind readers not to believe in chemical experiments that are offered ‘only by way of Prescriptions, and not of Relations’, by which latter term he means accounts by the experimenter of his own processes (SC A3[v]). For Boyle, ‘relations’ include even such fictional extensions into the social setting of scientific discourse. This is Carneades’s position, too—the reason, Boyle says, that so many have been willing to believe in Paracelsian theory is that they have not bothered to try out the experiments themselves or derived credible relations of them from trusted sources (SC A3[v]).80 Thus, much of the dialogue consists of what Carneades describes as a [Baconian] ‘demonstration’, rather than a [Scholastic] ‘harrangue’ (SC 25), as when Carneades describes an experiment in which he digested antimony in oil of vitriol and later distilled this by fire to produce sulphur ‘of so sulphureous a smell, that upon the unluting of the vessels it infected the Room with a scarce supportable stink’ (SC 68). The narrative of the process, with the memorable detail of the demotic ‘stink’, gives a clear sense of an actual event, a demonstration, rather than a precept. It is as if Boyle has realized that his natural gift for narrative and fictional detail is the very tool with which to present the demonstrations, rather than the precepts of natural philosophy.

Near the beginning of the Proemial Essay, Boyle describes the usefulness of narrative experimental accounts, even of misinterpreted data. He claims some virtue even in these, since such an essay

does me no greater injury than Galileo upon his first Invention of the Telescope would have done an Astronomer, if he had told him, that he had discover’d in heaven those imaginary new Stars which a late Mathematician has fancy’d himself to have descry’d there, and at the same time had made him a Present of an excellent Telescope, with expectation that thereby the Receiver should be made of the Giver’s Opinion; for by the help of his Instrument the Astronomer might not only make divers useful Observations in the Sky, and perhaps detect new Lights there, but discern also his mistake that gave it him. (Proemial, 11)

This is a remarkable expression of union between literary and mechanical technologies in science: in this analogy, the telescope and the narrative essay are alike tools of investigation, alike disinterested in conveying fact, even if that fact is open to misunderstanding. That Boyle should express the power of rhetorically fashioned scientific writing in such a striking similitude reminds us exactly how open to the rhetorical early modern science really was. ‘Such a way of proposing and elucidating things,’ he concluded at the end of his life, ‘is … more clear … than any other …’ (CV, 17–18).

Benjamin, Andrew E., Geoffrey N. Cantor, and John R. R. Christie, eds. The Figural and the Literal: Problems of Language in the History of Science and Philosophy, 1630–1800 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1987).

Boyle, Robert. An Account of Philaretus During His Minority in Robert Boyle by Himself and His Friends, ed. Michael Hunter (London: Pickering & Chatto, 1994).

Clucas, Stephen. ‘A Knowledge Broken’, in Neil Rhodes, ed., English Renaissance Prose: History, Language, and Politics (Tempe, AZ: Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 1997), 171–2.

Cummins, Juliet, and David Burchell, eds. Science, Literature and Rhetoric in Early Modern England (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007).

Harkness, Deborah E. ‘Francis Bacon’s Experimental Writing’, in Susannah Brietz Monta and Margaret W. Ferguson, eds., Teaching Early Modern English Prose (NY: Modern Language Association of America, 2010), 246–58.

Paradis, James. ‘Montaigne, Boyle, and the Essay of Experience’, in George Levine, ed., One Culture: Essays in Science and Literature (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987).

Preston, Claire. ‘In the Wilderness of Forms: Ideas and Things in Thomas Browne’s Cabinets of Curiosity’, in Neil Rhodes and Jonathan Sawday, eds., The Renaissance Computer: Knowledge Technology in the First Age of Print (London: Routledge, 2000), 170–83.

Principe, Lawrence M. ‘Virtuous Romance and Romantic Virtuoso: The Shaping of Robert Boyle’s Literary Style’, Journal of the History of Ideas, 56.3 (1995): 377–97.

Shapin, Steven. ‘Pump and Circumstance: Robert Boyle’s Literary Technology’, Social Studies of Science, 14 (1984): 481–520.

Vickers, Brian. ‘Bacon among the Literati: Science and Language’, Comparative Criticism, 13 (1991): 249–72.

——— ‘The Royal Society and English Prose Style: A Reassessment’, in Brian Vickers and Nancy S. Streuver, eds., Rhetoric and the Pursuit of Truth: Language Change in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Los Angeles: UCLA/Clark Library, 1985), 1–76.